Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of individually tailored dietary counseling on nutritional status among home care clients aged 75 years or older.

Design

Non-randomised controlled study.

Setting and participants

The study sample consisted of 224 home care clients (≥ 75 years) (intervention group, n = 127; control group, n = 100) who were at protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) or risk of PEM (MNA score <24 and plasma albumin <35 g/L).

Intervention

Individually tailored dietary counseling; the persons were instructed to increase their food intake with energy-dense food items, the number of meals they ate and their consumption of energy-, protein- and nutrient-rich snacks for six months.

Measurements

The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), Body Mass Index (BMI) and plasma albumin were used to determine nutritional status at the baseline and after the six-month intervention.

Results

The mean age of the home care clients was 84.3 (SD 5.5) in the intervention group and 84.4 (SD 5.3) in the control group, and 70 percent were women in both groups. After the six-month nutritional intervention, the MNA score increased 2.3 points and plasma albumin 1.6 g/L in the intervention group, against MNA score decreased -0.2 points and plasma albumin -0.1 g/L in the control group.

Conclusions

Individually tailored dietary counseling may improve nutritional status among older home care clients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The majority of older people aged 75 years or more would like to live in their own home instead of living in residential care (1). In addition, many countries, including Finland, have seen a substantial rise in expenditure and demand for home care services instead of residential care. The purpose of home care services is to support maintaining of health, functional abilities, quality of life and independent living, enabling clients to live at home for as long as possible (2). To be able to promote home care clients’ ability to live at home, these services and assistance at home should support these clients’ individual needs (1). Providing home care services based on a home care client’s personal needs is an increasingly pertinent issue.

Nutrition is important in maintaining good health, functional capacity and quality of life among older people (3, 4). Ageing is associated with decreased food intake, increased risk of malnutrition and loss of weight and muscle mass (3, 5). The quality of the diet is often poor and protein and other nutrient intake is low among older people (4, 6). Malnutrition is associated with poor health outcomes such as decreased physical ability, functional dependence, depression, cognitive impairment, chewing problems (7) and multiple comorbidities (8), and increased risk of infections (9), falls, fractures (10) and pressure ulcer development (11). Malnutrition increases the risk for mortality and higher morbidity (12). Malnourished persons also have a higher number of hospitalisations and hospital days, which cause higher health care costs (11, 13).

The risk of malnutrition or malnutrition is common among home care clients (49–86%), measured by the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) test (14, 15). The big differences in the prevalence of malnutrition risk or malnutrition may be caused by differences in the study populations and exclusion criteria used in the studies. For example, if persons with a severe cognitive impairment were excluded, the prevalence of malnutrition risk or malnutrition was lower.

There are only few dietary intervention studies among older people (16-18). These prior studies have been conducted in hospitals or nursing homes or among community-dwelling older people. As far as we know, there are no previous nutritional intervention studies among vulnerable home care clients. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of individually tailored dietary counseling on nutritional status among home care clients aged 75 years or older.

Methods

Study Sample

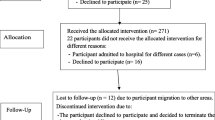

This study is part of the Nutrition, Oral health and Medication (NutOrMed) intervention study (19). The NutOrMed study was a non-randomised population-based multidisciplinary intervention study aimed at evaluating nutritional status, oral health and drug use among home care clients.

The study sample comprised home care clients aged 75 years or over living in three cities in Eastern and Central Finland. The population of this study consisted of home care clients who completed the MNA test, and the intervention was implemented only for those who were at protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) or risk of PEM (MNA score <24 and plasma albumin <35 g/L. The final study sample consisted of 227 clients, of whom 127 belonged to the intervention group and 100 to the control group.

At the baseline, all the clients were interviewed and examined at home by trained nurses, nutritionists, dental hygienists and pharmacists. Nutrition and oral health were measured at the baseline and after the six-month follow-up. Drug use was evaluated only at the baseline. We had no exclusion criteria regarding maximum age, morbidity or cognition. If a home care client was unable to reply (e.g., in cases of severe cognitive impairment), data collection was supplemented with an interview of a caregiver or nurse.

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District. All the participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study. In the case of clients with severe cognitive impairment, written informed consent to participate was obtained from a relative or caregiver.

Outcome variables

The nutritional screening was assessed with the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) test (14, 20). The MNA is a widely used and validated tool for detecting malnutrition and risk of malnutrition in older people. It involves a general assessment of health (questions regarding lifestyle, mobility and drugs), a dietary assessment (questions regarding type and number of meals), anthropometric measurements and a subjective self-assessment by the patient. The maximum sum score of the MNA is 30.0; scores of 24.0–30.0 indicate normal nutritional status, scores of 17.0−23.5 a risk of malnutrition and scores < 17.0, malnutrition. Plasma albumin levels were measured according to standard protocols at the regional laboratory, ISLAB (21). Body Mass Index (BMI) was computed as the ratio of weight to the square of height (kg/m2).

Background variables

Dry mouth was assessed by asking the participants “Do you have a feeling of dry mouth?” The question had three categories: 1 (no), 2 (occasionally) and 3 (continuously). Categories 2 and 3 were combined for the analyses. Regular and as-needed use of prescription and over-the-counter drugs was recorded by a pharmacist on the basis of the interview, medication lists and medication packages. Drug use was categorised into two classes: 0−9 and 10 or more drugs (10 or more drugs indicates excessive polypharmacy) (22). Ability to perform basic and complex daily activities was assessed using the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) test with the 10-item Barthel Index (23) and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) test with the 8-item Lawton and Brody scale (24). Scoring for the ADL index is 0–100 and for the IADL scale, 0−8, with higher scores indicating better functioning. Self-reported ability to walk 400 m was assessed by asking the participants, “Can you walk at least 400 m?” The question had four response categories: 0 (unable to walk), 1 (unable to walk independently) and 2 or 3 (able to walk independently with or without difficulty). Categories 2 and 3 were combined for the analyses. Cognitive status was evaluated with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) with a scale from 0 to 30 and higher scores indicating better function (25).

Nutritional intervention

Table 1 shows a description of the procedures in the intervention and control group. The six-month intervention was tailored and based on the baseline MNA test, plasma albumin level and 24-hour dietary recalls. The main aim of the intervention was to correct possible inadequacies in the clients’ diet and to recommend food items they were familiar with and which were already part of their daily diet. The clients in the control group did not receive interventions but were interviewed and measured at the baseline and after the six-month follow-up.

Each client had two nutritional treatment meetings with the authorized nutritionist, the first at the beginning of the study and the second after the six-month follow-up. During the first visit the authorized nutritionist examined the client’s weight, height and daily eating routines with 24-hour dietary recalls. She also collected important information, such as the client’s history of health problems, food preferences and appetite status. Nutritional status was evaluated with the MNA test and plasma albumin and nutrient intake by using the 24-hour dietary recalls. Based on this evaluation, the nutritionist developed a plan for individualised nutritional care together with the client and her/his nurse or relatives, if necessary. The nutritional care plan was developed only for those who were at protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) or risk of PEM (MNA score <24 and plasma albumin <35 g/L. Those with insufficient energy or protein intake, or with weight loss, were instructed to increase their food intake with energy-dense food items, the number of meals they ate and their consumption of energy-, protein- and nutrient-rich snacks. In lack of energy participants were advised to eat more frequently small meals during the day and to increase use of vegetable oil, margarine on slice of bread. In lack of protein participants were advised to use plenty of dairy products like milk as a drink, cheese on bread, snack with quark, yogurt, curdled milk and cottage cheese and to eat two hot meals daily.

Oral nutritional supplements (ONS) (Nutridrink Protein® (Nutricia) 300 kcal, 18 g protein) were given to those who had low energy or protein intake and were unable to change their diet with normal food items. Daily vitamin D (20-μg) supplementation was encouraged. In addition, the nutritionist gave advice on other food-related issues such as grocery shopping, cooking, appetite and possible eating-related problems. Three brochures were handed out. During the second visit the nutritionist re-examined the clients and made changes in their diet, if necessary. At the same time, the clients as well as their nurse or family members received instructions on how to follow the recommended diet.

Statistical analyses

The clients were categorized into two groups: an intervention group and a control group. Where the distribution of the change was approximately normal, statistical comparisons between the groups were made using an independent t-test or a chi-square test. When the data were not normally distributed, a Mann-Witney U test was used. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The results were expressed as means or frequencies with standard deviations (SD) or percentiles. The Mixed Model of linear regression was used to assess the effects of the nutritional intervention and the results were reported as adjusted (age, gender, MMSE and GDS-15 sum score) changes in MNA scores, plasma albumin and BMI. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

The mean age was 84.3 (SD 5.5) in the intervention group and 84.4 (SD 5.3) in the control group (Table 2). In the intervention group, 70.9% were female, compared with 70.0% in the control group. At the baseline, mean BMIs was significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the control group.

In the intervention group, the mean change in MNA scores was 2.3 (95% confidence intervals [CI]: 1.6 to 3.0) and in plasma albumin level, 1.6 g/l (95% [CI]: 0.1 to 3.2), while in the control group both changes were negative -0.2 (95% [CI]: -0.9 to 0.6) and -0.1 (95% [CI]: -1.0 to 0.9) g/l, respectively (Table 3). The intervention showed a significant effect on MNA scores (2.5, 95% [CI]: 1.0 to 3.3) and plasma albumin levels (1.5, 95% [CI]: 0.5 to 3.6) after adjustment for age, gender, MMSE and GDS-15. There were no differences in BMI change between the groups.

Discussion

This study shows that individually tailored dietary counseling can improve nutritional status among home care clients. This is an important finding because of the high prevalence of malnutrition or risk of malnutrition among this vulnerable population. This is especially important now, when the number of home care clients is rapidly growing because of the decrease in residential care.

Significant improvements in MNA scores and plasma albumin levels were observed in our study. This is in agreement with our previous findings among the general community-dwelling older population and Finnish study of AD persons living with a spouse (18, 26). We showed that individually tailored dietary counseling was effective in achieving better MNA scores and plasma albumin levels. Similar positive effects of dietary counseling on plasma albumin levels have been shown in older patients suffering from chronic kidney disease (27).

In the present study, BMI also increased in the intervention group, but the change was not statistically significant. This is in line with earlier studies which have shown an increase in MNA scores but no significant difference in BMIs (18, 28, 29). One explanation for this discrepancy may be that the MNA instrument measures more factors than just BMI and is therefore more sensitive to change.

Optimally, individually tailored nutritional care may improve clients’ nutritional status, reduce the length of hospital stays (30) and save health care costs (31). However, that is possible only if health care staff is able to screen malnutrition and to do nutritional interventions. This seems to be a great challenge, as Bauer and co-workers (32) found that nursing staff have knowledge deficits in screening and in assessment of nutritional status in nursing homes.

If home care personnel are not able to provide good nutritional care for home care clients, the shift in the focus of care for older people to home care instead of residential care will not succeed. To be able to respond to this major nutritional challenge, physicians and home care personnel need more education and training in proper nutrition in old age and in how to identify those at risk for malnutrition. In addition, they need to know how to improve the nutritional status of clients who are at risk of malnutrition or malnourished.

The strength of this study is its population-based design and multidisciplinary approach, as well as the individually tailored intervention model, which may be assumed to affect that dietary counseling was more likely to be adopted by the participants. The nutritional intervention was performed by the same authorized nutritionist, which improves internal reliability. Furthermore, this study had no exclusion criteria regarding the age and morbidity or the cognitive status of the home care clients. Hence, the findings of this study are directly applicable to real life. The study also has some limitations. The design of the study is weaker than a traditional randomised controlled trial, owing to randomisation having been done before the baseline measurements. On the other hand, a non-randomised population-based study design better describes real life than a randomised controlled trial, allowing health care professionals to focus on nutrition care among older people.

Conclusion

Individually tailored dietary counseling can improve nutritional status among home care clients. Nutritional screening and dietary counseling should be standard care among home care clients. More training is needed so that home care personnel can prevent and treat malnutrition.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02214758. Registered 12 August 2014.

Conflict of interest: The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical Standards: The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District (Finland).

References

Genet N, Boerma WG, Kringos DS, Bouman A, Francke AL, Fagerström C, Melchiorre MG, Greco C, Devillé W. Home care in Europe: a systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:207–6963–11–207.

National Institute for Health and Welfare. Institutional care and housing services in social care 2013. Available at: http://www.julkari.fi/. Accessed 6 December 2015.

Visvanathan R, Chapman I. Preventing sarcopaenia in older people. Maturitas 2010;66:383–388.

Anderson AL, Harris TB, Tylavsky FA, Perry SE, Houston DK, Hue TF, Strotmeyer ES, Sahyon NR; Health ABC Study. Dietary patterns and survival of older adults. J Am Diet Assoc 2011;111:84–91.

Vikstedt T, Suominen MH, Joki A, Muurinen S, Soini H, Pitkälä KH. Nutritional status, energy, protein, and micronutrient intake of older service house residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;12:302–307.

de Groot CP, van den Broek T, van Staveren W. Energy intake and micronutrient intake in elderly Europeans: seeking the minimum requirement in the SENECA study. Age Ageing 1999;28:469–474.

Nykänen I, Lonnroos E, Kautiainen H, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Nutritional screening in a population-based cohort of community-dwelling older people. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:405–409.

Saka B, Kaya O, Ozturk GB, Erten N, Karan MA. Malnutrition in the elderly and its relationship with other geriatric syndromes. Clin Nutr 2010;29:745–748.

Scrimshaw NS, SanGiovanni JP. Synergism of nutrition, infection, and immunity: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66:464S–477S.

Drevet S, Bioteau C, Maziere S, Couturier P, Merloz P, Tonetti J, Gavazzi G. Prevalence of protein-energy malnutrition in hospital patients over 75 years of age admitted for hip fracture. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014;100:669–674.

Verbrugghe M, Beeckman D, Van Hecke A, Vanderwee K, Van Herck K, Clays E, Bocquaert I, Derycke H, Geurden B, Verhaeghe S. Malnutrition and associated factors in nursing home residents: a cross-sectional, multi-centre study. Clin Nutr 2013;32:438–443.

Vanderwee K, Clays E, Bocquaert I, Gobert M, Folens B, Defloor T. Malnutrition and associated factors in elderly hospital patients: a Belgian cross-sectional, multicentre study. Clin Nutr 2010;29:469–476.

Correia MI, Waitzberg DL. The impact of malnutrition on morbidity, mortality, length of hospital stay and costs evaluated through a multivariate model analysis. Clin Nutr 2003;22:235–239.

Soini H, Routasalo P, Lagstrom H. Characteristics of the Mini-Nutritional Assessment in elderly home-care patients. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;58:64–70.

Kaipainen T, Tiihonen M, Hartikainen S, Nykänen I. Prevalence of risk of malnutrition and associated factors in home care clients. Jour Nursing Home Res 2015;1:47–51.

Gazzotti C, Arnaud-Battandier F, Parello M, Farine S, Seidel L, Albert A, Petermans J (2003) Prevention of malnutrition in older people during and after hospitalisation: results from a randomised controlled clinical trial. Age Ageing 2003;32:321–325.

Lorefalt B, Wilhelmsson S. A multifaceted intervention model can give a lasting improvement of older peoples’ nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16:378–382.

Nykänen I, Rissanen TH, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Effects of individual dietary counseling as part of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) on nutritional status: a population-based intervention study. J Nutr Health Aging 2014;18:54–58.

Tiihonen M, Autonen-Honkonen K, Ahonen R, Komulainen K, Suominen L, Hartikainen S, Nykänen I. NutOrMed-optimising nutrition, oral health and medication for older home care clients-study protocol. BMC Nutrition. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s40795-015-0009-7.

Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. Nutr Rev 1996;54:S59-65.

Cabrerizo S, Cuadras D, Gomez-Busto F, Artaza-Artabe I, Marin-Ciancas F, Malafarina V. Serum albumin and health in older people: Review and meta analysis. Maturitas 2015;81:17–27.

Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:514–522.

van der Putten JJ, Hobart JC, Freeman JA, Thompson AJ. Measuring change in disability after inpatient rehabilitation: comparison of the responsiveness of the Barthel index and the Functional Independence Measure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1999;66:480–484.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–186.

Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA 1993;269:2386–2391.

Suominen MH, Puranen TM, Jyväkorpi SK, Eloniemi-Sulkava U, Kautiainen H, Siljamäki-Ojansuu U, Pitkalä KH. Nutritional Guidance Improves Nutrient Intake and Quality of Life, and May Prevent Falls in Aged Persons with Alzheimer Disease Living with a Spouse (NuAD Trial). J Nutr Health Aging 2015;19:901–907.

Campbell KL, Ash S, Davies PS, Bauer JD. Randomized controlled trial of nutritional counseling on body composition and dietary intake in severe CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2008;51:748–758.

Hoekstra JC, Goosen JH, de Wolf GS, Verheyen CC. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary nutritional care on nutritional intake, nutritional status and quality of life in patients with hip fractures: a controlled prospective cohort study. Clin Nutr 2011;30:455–461.

Salva A, Andrieu S, Fernandez E, Schiffrin EJ, Moulin J, Decarli B, Rojano-i-Luque X, Guigoz Y, Vellas B; NutriAlz group. Health and nutrition promotion program for patients with dementia (NutriAlz): cluster randomized trial. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:822–830.

Holyday M, Daniells S, Bare M, Caplan GA, Petocz P, Bolin T. Malnutrition screening and early nutrition intervention in hospitalised patients in acute aged care: a randomised controlled trial. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16:562–568.

Elia M, Russell CA, Stratton RF. Malnutrition in the UK: policies to address the problem. Proc Nutr Soc 2010;69:470–476.

Bauer S, Halfens RJ, Lohrmann C. Knowledge and Attitudes of Nursing Staff Towards Malnutrition Care in Nursing Homes: A Multicentre Cross-Sectional Study. J Nutr Health Aging 2015;19:734–740.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pölönen, S., Tiihonen, M., Hartikainen, S. et al. Individually tailored dietary counseling among old home care clients - Effects on nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging 21, 567–572 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0815-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0815-x