Abstract

Internet has led to radical changes in commercial relations and especially in consumer buying habits. Considering the peculiar characteristics of Internet shopping, it is difficult to engender consumer online trust and consumer face an adverse selection problem when having to choose the best web site to buy from. This problem may be mitigated by signaling the high-quality and good behavior of the e-vendor or by consumer satisfactory experiences. As gender can make differences in the decision-making processes of individuals, the purpose of this study is to find out if there are gender differences regarding the effect of three specific signals of quality—service quality, warranty, and security and privacy policies– on e-satisfaction and e-trust, and on the relation between satisfaction and trust. The research questions were tested using information gathered from Spanish online buyers and using structural equation modeling. Results suggest that suitable gender-based signaling strategies could conceivably be prepared in accordance with the target population, which holds interesting implications for both the academic and the professional world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Consumer trust in a web site is essential in the context of e-commerce. Unlike conventional distribution channels where personal relations may develop, a company that sells online has to gain the trust of the consumer through its web site. Multiple studies mention trust as a key variable in the expansion of B2C e-commerce (Bart et al. 2005; Belanger et al. 2002; Vrechopoulos et al. 2004; Hwang 2009) and it is relevant in situations of uncertainty (Ha 2004). Here, we examine satisfaction and three web site characteristics—privacy and security policies, warranty, and service quality—as determinants of e-trust. When having to choose a web site to buy from, consumers face an adverse selection problem (Singh and Sirdeshmukh 2000), which involves a situation of uncertainty and information asymmetry because the e-vendor has more information than consumers and could cheat regarding its behavior or the quality of the products or services sold online. Following the signaling theory, e-vendors can send signals to the market to indicate that they are good providers and help consumers to make an appropriate decision. Consumers can infer quality using those signals or by their own satisfactory experiences. The proposed model, therefore, contemplates quality signals and satisfaction as antecedents of e-trust. However, there can be differences in that model according to consumer gender and that is why the objective of this study is to analyze the moderating effect of gender on the relationships between the above-mentioned determinants and consumer online trust. Some studies have analyzed gender-based attitudinal differences between males and females in relation to the use of Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) and in online selling contexts (Mittal and Kamakura 2001; Floh and Treiblmaier 2006). However, we have found no empirical studies that analyze the moderating role of gender on the influence of satisfaction on trust or its moderating role on consumer evaluation of signals that determine e-trust. The conclusions and the empirical evidence on this study will be of use to companies that sell online, for example, to design gender-based Internet marketing strategies. Besides, the explanatory and predictive capacity of consumer behavior models for the consumer improve when moderating variables are introduced (Batra and Sinha 2000; Mittal and Kamakura 2001).

Following this introduction, the structure of the paper is as follows: the second section describes the main variables of the study. The third section justifies the moderating influence of gender on the relations among the main variables of the model and includes the proposed research questions. The fourth section focuses on the empirical study. Finally, the fifth section sets out the main findings and the principal implications of the study.

Key variables in online purchasing

Consumer online trust and satisfaction

Trust and satisfaction in online contexts are essential in order to maintain a relationship with the consumer. Trust in an online context implies, more than ever, the consumer’s willingness to accept a degree of vulnerability towards the company, and the belief that the firm will fulfill its promises and will not exploit that vulnerability for its own benefit (Ranaweera et al. 2005). Trust creates positive attitudes towards the future behavior of the firm and it influences buying intentions, satisfaction and consumer loyalty (Ganesan 1994; Gefen 2000; Yoon 2002). Several researchers have analyzed the key role of trust and its relation with the evolution of electronic commerce and with loyalty towards a web site (Gefen 2000; Harris and Goode 2004). Lack of trust is the most prominent barrier to the growth of electronic commerce (Gefen 2000; Yoon 2002; Corbitt et al. 2003), which in turn affects the belief or emotional security felt by consumers that a web site will fulfill their expectations and will deliver the expected results, especially when making online payments and sharing personal data. There is low e-trust especially for operations that require credit-card data (about half of Spanish Internet users indicate that they have little or no trust) and for online stock exchange transactions (more than 60% have little or no trust) (INE 2009).

A primary objective for fostering B2C e-commerce is to mitigate the lack of consumer confidence (Yoon 2002; Ha 2004), and to increase consumer satisfaction in each transaction. The concept of satisfaction implies the fulfillment of expectations as well as a positive affective state based on previous results and the existing relationship with the web site. In the context of online purchasing, the literature highlights the importance of achieving buyer satisfaction to promote long-term relations between the firm and the consumer and to ensure the profitability of the online business (Ranaweera et al. 2005; Shankar et al. 2002). Satisfaction is also essential to reduce consumer uncertainty over the e-vendor honesty and to increase the intention to provide products and services in an efficient manner.

Although the general level of online trust is low (54% of Spanish Internet users state that distrust is their main reason for not shopping on Internet), practically all consumers (98%) that have purchased online in Spain express their satisfaction with the transaction (ONTSI 2009). Signaling theory is a theoretical approach that it is useful to address consumer adverse selection problem. This theory suggests that consumers can use web site–related mechanisms to infer the quality of the product or the performance of the store, be satisfied with and trust the web site, and finally decide from which virtual store to purchase. Next, the role of these web site characteristics as quality signals that the e-vendor can use is discussed.

Web site characteristics (quality signals)

Unlike traditional distribution channels, in which personal relations develop, in the online selling context, the web site is the main means available for companies to transmit trust and fulfill consumer expectations (Vrechopoulos et al. 2004). Web site characteristics can act as signals and communicate information to the shopper in contexts in which there is information asymmetry such as in online contexts. Some characteristics analyzed in literature, usually from a theoretical point of view, are: warranty, reputation, advertising, brand, web site’s security and privacy policies; price premium; and, detailed and objective information on the product (Emons 1988; Tan 1999; Biswas and Biswas 2004; Fiore 2002; Anderson and Weitz 1992; Hawes and Lumpkin 1986; Bagwell and Ramey 1988; Nelson 1974; Bart et al. 2005; Rao et al. 1999; Teas and Agarwal 2000; Hoadley et al. 2010). In this study, we will only consider attributes that may be ascribed to the web site and objectively discerned by the user, which are cognitively assessed in terms of their capacities, and which have some bearing on the honesty of the e-vendor (Williams 2002). The specific web site characteristics –quality signals- we will use in this study refer to policies on security and privacy, warranty and service quality. Other collateral signals that might simultaneously appear on the web site, but which are secondary to the core of the purchase decision, will not be taken into consideration.

In a similar way, Lee and Overby (2004) differentiate between experiential value for online shoppers—such as benefits from entertainment, escapism, visual appeal and interactivity associated with online shopping -, and utilitarian value—which represents the assessment of functional benefits (price and time savings, service excellence and selection). Wolfinbarger and Gilly (2003) also identify two types of behavior among online customers: experience-based behavior (buying for fun and enjoyment, prompted by more emotional drives) and goal-oriented or utilitarian shopping (task-oriented, efficient, rational, and deliberate, which relate more to cognitive processes).

Security and privacy policies

It is widely accepted that security and privacy of online transactions are the main attributes of an online store that provide reassurance to customers when making their decisions. Customers whose awareness of security and data privacy is greater will be more likely to use e-commerce; simple and straightforward access to the security and privacy policies of the web site may help to develop such awareness. In the case of electronic banking, Yousafzai et al. (2005) and Kassim and Abdullah (2010) demonstrate that clarifying security and privacy policies leads to the customers developing satisfaction and trust. According to Wang et al. (2004), providing privacy (and security) disclosures is an effective way for online retailers to develop cooperative relationships with shoppers. According to Gattiker et al. (2000); Maditinos and Theodoridis (2010); Ruparelia et al. (2010); Featherman et al. (2010), privacy and security policies are one of the most important consumer concerns in the information era, and in consequence, we consider that this web characteristic should have especial importance in an online setting. Lee et al. (2005) argue that privacy (and security) policies convey signals of e-vendor integrity. Thus this signal communicates e-vendor abilities, benevolence, integrity and predictability in terms of handling online transactions and can also generate or enhance consumer satisfaction with their online shopping experience.

Warranty

The warranty reflects firm commitment to fulfill its promises. It relates to service quality and to the fulfillment of consumer expectations and appears in the form of an explicit contract, which details solutions to future contingencies such as faulty products (Emons 1988). It may be assumed that a firm that provides low-quality services will not be interested in offering a high-quality warranty, as this would imply higher costs than in the case of a high-quality service, due the probability of more complaints. Warranties have been depicted as a means to reduce the uncertainty and risk perceived by the consumer and the negative consequences that the consumer faces if a product failure occurs (Bearden and Shimp 1982; Tan 1999). Without a warranty, the goods are sold on the condition that the seller has no responsibility for any faults or imperfections in the goods, and the buyer has no right to return them or claim damages (Loomba 1998). A good warranty should therefore encourage customers to have more confidence in a service firm and impact consumer judgment, including satisfaction (Ostrom and Iacobucci 1998; Qin et al. 2009). Leniency with regard to the policy on returns is one way to foster satisfaction and trust in remote purchase environments, including online shopping (Tan 1999; Wang et al. 2004).

Service quality

In an online context, service quality may be reflected by a firm’s efforts to provide better service through a wide assortment of products, a good quality-price ratio, a good delivery service, detailed information on products and services and greater customization (Trocchia and Janda 2003; Yoon and Kim 2009). Previous literature has highlighted the relation between service quality and trust and satisfaction in several cases, including online contexts (Feinberg and Kadam 2002; Harris and Goode 2004; Gummerus et al. 2004; Ribbink et al. 2004). Singh (2002) suggests that online customers harbor increasing expectations with regard to the services offered to enhance their online shopping experience. As perception of security and privacy risk decreases, satisfaction with the information service is expected to increase (Ha 2004; Park and Kim 2003, 2006).

Once signals, trust and satisfaction have been defined, the following section deals with the role that gender plays in online purchasing to study afterwards the moderating effect of gender on the relations among signals, trust and satisfaction in an online context.

The role of gender in online contexts

Consumer characteristics are relevant to the perception of company signals and to the development of satisfaction and trust. Thus, we introduce personal characteristics (demographic and socio-economic variables) as variables that have an effect on consumer perceptions and, as a result, on the overall model. Previous literature shows that personal characteristics, such as gender, age and educational level, have an impact on relationships (Gattiker et al. 2000; Meyer and Allen 1991; Moorman et al. 1993; Nooteboom et al. 1997; Shemwell et al. 1994).

Previous studies have shown that demographic and contextual characteristics such as age (Yalch and Spangenberg 1990), educational level (Gattiker et al. 2000; Tamimi and Sebastianelli 2007), income levels (Dawson et al. 1990) and gender (Zhang et al. 2007; Kolsaker and Payne 2002) are factors that influence the purchase experience. In that sense, the individual’s personal characteristics have an important role in their perception of company signals and in the development of satisfaction with online purchasing and trust in a web site. Demographic characteristics may also moderate the variables that influence online purchasing behavior, approval and implementation of the new information technologies (Baker et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2007). Some research indicates that the older the consumers, the less their involvement in the process of searching and analyzing information (Gilly and Zeithaml 1985). Moreover, Homburg and Giering (2001) affirm that personal characteristics, such as gender, age and income, have a moderating influence on the satisfaction-loyalty relationship.

Although some studies exist on the importance of gender in the online context, empirical evidence regarding the moderating role of this variable on the relation between trust and online satisfaction and several other web site characteristics remains scarce and even less applying the signaling theory.

Our study focuses on nurture as the root of the proposed gender difference. Gender is defined as “a psychological phenomenon that refers to learned sex-related behaviors and attitudes of males and females” (Gerrig and Zimbardo 2002). Literature suggests that while the term sex is used when referring to purely biological factors (nature), the term gender is used when referring to cultural aspects (Helgesen and Nesset 2010). Therefore, gender differences are social constructions (Gentry et al. 2003; Sidin et al. 2004). Consequently, females and males tend to have different attitudinal and behavioral orientations, partly from genetic makeup, but mainly from socialization experiences (we mention some of these experiences in the empirical study section). Thus, Smith (1998) points out that the gender of both parties to a relationship influences the quality of the relationship and the way it is managed. Likewise, Gilligan (1982) find that females were able to develop relationships more easily than males, and that they show higher levels of trust and commitment.

Empirical evidence on gender influencing individual behavior is contradictory. Nevertheless, we believe this line of research is worth pursuing, because it is one of the most commonly used variables in market segmentation and selection of the target population, due to its accessibility and simplicity. Indeed, the majority of the articles reviewed in this paper establish gender differences in relation to online purchasing, and only a minority fails to do so (Bonn et al. 1998; Roehl 2001). Attitudinal and behavioral differences between males and females in an online context have been investigated in some empirical studies on the adoption of technology for online shopping, and the use of e-mail and online banking (Lichtenstein and Williamson 2006; Chang and Samuel 2004; Rodgers and Harris 2003; Gattiker et al. 2000; Luo et al. 2006). Specific differences are noted in previous studies, which have established that females are often more involved in purchase activities (Gilbert and Warren 1995), pay more attention to the salespeople (Citrin et al. 2003), are more concerned about privacy, and attach greater value to relationships with salespeople (Slama and Tashlian 1985). On the other hand, we also know that the predominant profile of the Internet user in Spain corresponds males (ONTSI 2009), that males seek to develop their own identity, and they are more independent in their purchase process and have more utilitarian motives when buying (Citrin et al. 2003). Literature determines two main gender differences that condition consumer buying behavior: (1) males are more pragmatic and are primarily guided by societal norms that require control, mastery and self-efficacy to pursue self-centered goals, while (2) females experience greater anxiety when facing new activities, and put emphasis on affiliation and harmonious relationships with others (Sun and Zhang 2006; Ndubisi 2006). Goldsmith and Flynn (2004) find that unlike age or income levels, gender was the most relevant variable pertaining to the online purchase of clothing (females bought more clothing online than males).

The impact of gender on the antecedents of online satisfaction and trust

The moderating role of gender on the relation between online satisfaction and trust

Szymanski and Hise (2000) indicate the need to study the antecedents of online satisfaction and in particular the link between trust and satisfaction. The degree of overall consumer satisfaction with previous exchanges has been identified as an important antecedent of consumer attitude (Oliver 1980) and trust (Ravald and Grönroos 1996; Selnes 1998). A series of positive encounters will serve to increase consumer satisfaction and will therefore enhance trust and increase the likelihood of repeat purchasing (Morgan and Hunt 1994; Selnes 1998). Authors such as Ravald and Grönroos (1996), Selnes (1998), and Lau and Lee (1999) propose the positive influence of satisfaction on trust in an off-line context, and authors such as Ribbink et al. (2004) support it in an online context. Park and Stoel (2005) point out that even if consumers are unable to touch, feel, or try on a product, satisfactory purchasing experiences will lead consumers to perceive fewer dangerous consequences than consumers who have no previous purchase experiences.

Nevertheless, gender differences may well exist between males and females. Although we have yet to find any studies in the literature that support this moderating effect, Floh and Treiblmaier (2006) suggest that, in theory, different personal characteristics, such as gender, age, educational level and income level have a moderating effect on the relation between satisfaction and trust. Ndubisi’s study (2006) on offline banking services affirms that females prefer durable and stable relations with an access provider. In the case of females, that study confirms that higher levels of trust will be generated, provided that the company establishes a relation based on the accumulation of positive previous experiences (satisfaction). According to the findings of Archer (1996) and Eagly (1987) studies, females are less willing than males to take risks. As it is riskier for females to switch providers and try something new, they will tend to look for solid relationships, also in virtual contexts. In this situation, the experience of previous satisfactory transactions may act as a protective mechanism to avoid risk and trust. Thus, females will react more strongly to satisfaction level changes.

-

RQ1:

Is the influence of web site satisfaction on web site trust greater for females than it is for males?

The moderating role of gender on the relation between web site characteristics (quality signals) and online satisfaction and trust

As already stated, security and privacy policies, warranty and service quality are web site characteristics that directly affect trust in the web site, as they are signals of the vendor capacity and goodwill, but such signals may also affect buyer satisfaction and consequently their trust in the vendor once they have made an online satisfactory purchase (Lee and Lin 2005; Park and Kim 2003; Rodgers and Harris 2003; Maditinos and Theodoridis 2010; Wang et al. 2004; Wood 2000). In this way, signals help consumers to solve their adverse selection problem.

It is expected that the aforementioned relations will differ in accordance with the gender of the online buyer. In the first place, we propose that security and privacy policies have a greater effect on female online trust. Following the line adopted by O’Neil (2001), studies should examine gender differences relating to concerns over the degree of Internet privacy. Following Karande et al. (2007), we state that females use online communication as a means of building and sustaining relationships, whereas males prefer task-oriented communications. Thus, males place less importance on relational aspects (such as trust) but emphasize outcome aspects (such as satisfaction). Females give greater importance to elements that might mitigate any possible loss in the establishment of online relationships because of being more risk-averse in decision making (Bartel-Sheehan 1999; Citrin et al. 2003; Garbarino and Strahilevitz 2004; Tamimi and Sebastianelli 2007). Thus, privacy and security policies have a greater effect on their trusting beliefs than in males ones (research questions RQ2a). Conversely, we expect that privacy and security policies have a greater effect on male satisfaction because males give more weight to the shopping motivation of convenience seeking than females (Noble et al. 2006). From this point of view, privacy and security policies save customer time to solve the important future problems, and this could provoke that they have a greater effect on male satisfaction than females (research question RQ2b).

In the second place, we look at the moderating role of gender on the effect of the warranty on trust. Ostrom and Iacobucci (1998) distinguish between relational aspects (the warranty guarantees the way in which customers should be treated or the return period or waiting time) and essential aspects (such as the extension of the warranty or the amount that is reimbursable) of warranties associated with particular services. Iacobucci and Ostrom (1993) suggest that the essential aspects of a warranty lead more often to a positive evaluation of a web site by males, whereas females are more sensitive to the relational aspects of the warranty. Iacobucci and Ostrom (1993) and Ostrom and Iacobucci (1998) emphasize that it is essential to consider the specific aspect of the warranty that is under evaluation by the consumer, in order to determine any differences in the importance accorded to warranty by either males or females. In our study, consumers evaluate the essential aspects of the warranty and not the relational aspects, as in most studies about warranty (Gattiker et al. 2000; Corbitt et al. 2003; San-Martín and Camarero 2008). We therefore propose that the influence of the warranty on trust is greater in the case of males than in the case of females (research question RQ3a). Ndubisi (2006) suggests that “objective” and “logical” are more male-valued traits, and males are more task-oriented than females. In this line, we expect that warranty have a greater effect also in males’ satisfaction because it represents “a legal safeguard” and a relative reduction of cognitive uncertainty on e-shopping (Rierdan et al. 1982) (research question RQ3b).

In the third place and with respect to service quality, we propose that its influence on trust is greater for females than it is for males (research question RQ4a). As previously mentioned, females value relational aspects of the purchase more than males (Iacobucci and Ostrom 1993) as well as the delivery system and after-sales support (Burke 2002). In consequence, we believe that female trust will be based on personalization of products and services, product variety, delivery conditions and deadlines, and the available information, all of which are aspects of service quality. Compared to males, females are more involved in purchasing activities (Slama and Tashlian 1985), and pay more attention to the shopping motivation of social interaction than males (Chen and Chiu 2009; Gilbert and Warren 1995). Thus, we expect that the effect of service quality on trust and satisfaction will be higher in females than in males (research question RQ4b). Therefore,

-

RQ2.

(a) Is the effect of privacy and security policies on trust greater for females than it is for males?; (b) Is the effect of privacy and security policies on satisfaction greater for males than it is for females?

-

RQ3.

(a) Is the effect of the warranty on trust greater for males than it is for females?; (b) Is the effect of the warranty on satisfaction greater for males than it is for females?

-

RQ4.

(a) Is the effect of service quality on trust greater for females than it is for males? (b) Is the effect of service quality on satisfaction greater for females than it is for males?

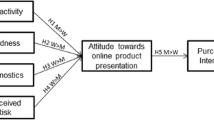

Figure 1 depicts the four proposed research questions described above. The methodology and the results are discussed in the following sections.

Empirical study and results

Sample

In order to test the proposed research questions depicted in Fig. 1, we based our empirical study on information gathered through a questionnaire given to online shoppers. The population from which the sample was drawn is comprised of Spanish online shoppers and the sampling technique used was semi-random (Birn 2000), since the questionnaires were randomly sent to several Internet-centers (public and private) and agents and supervisors were told to make personal interviews to all the Internet users that entered the cyber-centre and that had bought online at least once. The goals of this sampling method were to gather information from individuals living in different Spanish regions, with different personal characteristics and different levels of Internet expertise, and also to guarantee that they were Internet users and knew the channel which they are asking about. In fact, 83% of our sample is composed of moderate shoppers (bought on Internet sporadically). The questionnaire asked each participant to name a web site where he or she most used to shop and participant subsequent evaluation in terms of quality signals, e-satisfaction and e-trust was conducted on that specified web site.Footnote 1 The survey, which took place over the months of May, June and July 2009, formed a sample of 533 individuals. After an initial filtering process that eliminated 26 questionnaires due to incompleteness or wrong answers, the final sample comprised 507 individuals. Table 1 shows the sample divided by gender, age and educational background and compares it with the Spanish Internet buyer profile according to information provided by the Spanish Association of E-Commerce.Footnote 2

Previously to explain the research method employed, it is appropriate to clarify whether the effect of gender is due to nature or nurture (Deaux 1984). With this idea in mind, in the questionnaire some socialization experiences were asked to interviewees and a chi-square difference shows that there are some significant differences that can be underlying causes of nurture gender divergences [(Experience of online buying: χ2 = 13.63, d.f. = 4, p = 0.009); (Experience of using Internet: χ2 = 12.89, d.f. = 4, p = 0.012)].

Variable measures

Relevant reference literature was used to ensure the content validity of the measures. The variables were measured on a 5-point Likert question scale anchored by strongly disagree with to strongly agree with. Appendix 1 details the proposed scales and their corresponding descriptions. The web site attributes proposed in the model are security and privacy policies, warranty and service quality. The indicators are based on studies by Burke (2002), Montoya-Weiss et al. (2003), Harris and Goode (2004), Ranaweera et al. (2005) and Yadav and Varadarajan (2005), although some indicators were specifically adapted for this study and tested in previous works done by the authors. In order to measure web site characteristics (each quality signal), an index was created from the average of the corresponding items. Thus, a six-item scale measured security and privacy policies, which referred to the company security regarding data protection, information provided on security and the existence of reliable data transmission mechanisms. Web site warranties were measured with two indicators: warranty against failure and refund warranty. Five indicators provided a measure of service quality that refer to the information provided, compliance with deadlines, product range, the price-quality level and the range of customized products and services.

Satisfaction was measured using a six-item scale based on Oliver’s proposal (1980) and adapted to online purchasing by referring to Montoya-Weiss et al. (2003), Bennett et al. (2005) and Harris and Goode (2004). Trust is conceived of in terms of unidimensional latent variables that reflect a whole concept, which is widely accepted in previous investigations (Morgan and Hunt 1994; Anderson and Weitz 1992; Bart et al. 2005; Moorman et al. 1993; Doney and Cannon 1997; Harris and Goode 2004). In order to ensure the content validity, trust was measured through eight widely accepted items, taking as a reference well-known studies in the offline context (Ganesan 1994; Doney and Cannon 1997) and in the online context (Harris and Goode 2004 and Roy et al. 2001). With the selected items we have tried to capture especially the aspects of competence, integrity and benevolence that McKnight et al. (2002) point out as very relevant aspects of trust in and online context.

In the preliminary analysis, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted (using SPSS 11.5) to ensure the unidimensionality of the latent variable measurements (Appendix 1). Subsequently, structural equation modeling was the methodology followed to estimate the model, as it is a well accepted and robust methodology in marketing research (Baumgartner and Homburg 1996), specially adequate to analyze several equations that reflect causal relations between latent variables (Fornell 1982). The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) carried out with LISREL programme is very useful to appreciate the validity of the measurement model (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993; Reinartz et al. 2009). Attending Chin (1995) suggestions, LISREL provides a statistical basis using a chi-square test for multiple group comparison. CFA serves to obtain the definitive scales and determine the convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993; Bagozzi and Baumgartner 1994) (Appendix 2). It may be confirmed that the direct relation between each construct and their corresponding measurements were significant to a 95% level in all cases (t > 1.96). After validating the convergence of the scales, we calculated the correlation matrix of the factors. In all cases, the extracted variance of each variable exceeded the value of its squared correlation with the other variables, thereby justifying the discriminant validity of the scales (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). Then, the proposed research questions were tested by means of a multigroup analysis using a structural equation analysis, the most appropriate technique when having to analyze the moderating effect of a variable on relations among latent variables (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1993).

Estimation of the proposed model

The next step of the analysis was to estimate the effect of the web site characteristics on satisfaction and trust as well as the moderating role of gender. First, the model was estimated taking into consideration identical coefficients for males (267) and females (232) (Table 2). Second, the multigroup model was estimated, leaving the parameters free for each group (Tables 2 and 3). In both cases, the goodness-of fit indicators are positioned within the suggested limits and are considered as proof of a good fit. However, after introducing the moderating effect of gender, the model goodness-of-fit improves, showing a significant decrease in the chi-square value.

With respect to the effect of the three web site characteristics (quality signals) and satisfaction on trust and irrespective of the influence of gender in the model, all the relations between the proposed variables are significant and the model fits well. A more detailed comparison of the moderating effect on the relations of the relations among the model variables provides empirical support for several significant differences between group 1 (females) and group 2 (males). An estimation of model parameters that takes account of the moderating role of gender in each relation fails to provide empirical support for the RQ1, because online satisfaction influences trust in a similar way for males and for females. However, the results point to a moderating effect of gender on the relation between trust and privacy and security policies (RQ2a), whereas there is no moderating effect in the case of the warranty (RQ3a). Regarding the effect of web site characteristics on satisfaction, our results show that gender moderates the influence of privacy and security on satisfaction (RQ2b) and the effect of warranty on satisfaction (RQ3b). Finally, our results show that both satisfaction and trust appear to be equally affected by service quality (RQ4 a and b).

In addition and despite it was not the main purpose of this paper, we tested the global moderating effect of other demographic characteristics (age, educational level, income level and occupation). Our study also tries to determine if some characteristics globally influence the overall model (Table 4).

The results show that only the educational level has a global moderating effect. In the next section we discuss the results in more detail.

Discussion of findings

Several scholars have examined the impact of customer satisfaction on e-trust, but only relatively recently have researchers begun to argue that the link is more complex than previously suggested (Homburg et al. 2003; Chung and Shin 2010). First, contrary to expected, gender does not have a moderating role on the satisfaction-trust link. Satisfaction with previous experiences is a key aspect in the generation of trust for both groups, which indicates that once a buyer is pleased with a web site, that should be enough to generate trust in the e-vendor and the web site, irrespective of buyer gender. Other studies have also failed to identify gender differences in certain phases of purchase, e.g. Bonn et al. (1998) when studying the tendency to search for travel-related information on the Internet. Likewise, Roehl (2001) found that gender did not greatly influence online purchase behavior, although it is influential in the specific context of searching for information. Moreover recent research has found no statistically significant differences between males and females with regard to Internet use (Chung and Shin 2010; Hernández et al. 2010). One possible justification for this fact is that gender-related differences disappear when the experience acquired by individuals during the online purchasing process causes their behavior to evolve and gender differences cease to be so when it comes to making repurchase decisions.

Another important contribution of our study comes from the lack of empirical studies that analyze the moderating effect of gender on the effect of quality signals on satisfaction and trust. In this sense, it can be affirmed that certain web site characteristics perform better as quality signals and contribute more than others to the generation of consumer e-satisfaction and e-trust. The results confirm that gender is a determinant -directly and indirectly- in the way a decision is taken. Females feel confident on the web site when they perceive that the company offers to protect their privacy and guarantees security in their online transactions. This result is consistent with the relevance of security in online purchasing for females, as established by certain studies performed in other countries (Luo et al. 2006; Tamimi and Sebastianelli 2007). In addition, taking into account the scarcity of studies that considers the moderating effect of gender on the relations between quality signals, satisfaction and e-trust, our work contributes to better understand how gender affects the individual acceptance and propensity of e-commerce. Our results show that privacy and security policies have a greater impact on male satisfaction than on females. Security and privacy concerns seemed to be based on emotional questions (for females) and on objective knowledge (for males). This result empirically confirms what some authors theoretically suggest (Karande et al. 2007).

On the other hand and with caution, we could affirm that male buyers may show greater satisfaction and trust more in those sites that offer a warranty, whereas the warranty does not have a significant effect on female online satisfaction and trust. Our findings also indicate that service quality influences trust towards the web site in similar ways, regardless of gender. The absence of a significant moderating effect can be due perhaps to the fact that service quality is a variable that encompasses many aspects, what demands further investigation. Another interesting finding of the present study is that the influence of service quality on satisfaction is higher than its influence on trust. We can therefore suppose that it influences trust only if it is capable of generating consumer satisfaction. Service quality may be better experienced when the consumer has online experience and if this is satisfactory, it may be expected to lead to e-trust (Helgesen and Nesset 2010). Finally, our results show that another socio-demographic characteristic that can moderate the model is the individual educational level and it is also desirable that future studies deal with this topic.

Conclusions and implications

Theoretical implications

This work is relevant to the e-commerce literature as it shows how to get online trust and satisfaction. We should not forget that it is more difficult to retain consumers in an online context, because there are a large number of alternatives, and consumers face an adverse selection problem when buying online. Online purchases, where the absence of trust represents a major obstacle, also compete with physical retail outlets. Hence, aspects such as service quality, warranty, privacy and security policies can be decisive in developing consumer satisfaction and trust. The main purpose of this study has centered on analyzing whether the online signals emitted by a company and consumer satisfaction affect customer trust in the web site in different ways, according to the gender of each consumer. The contributions of this study are as follows. (1) To the extent of our knowledge, there are no studies that empirically apply the signaling theory to study the influence of web site characteristics on e-trust and e-satisfaction; (2) we have found relevant gender-related differences in each one of the relations among the variables used in the study; and (3) a wide sample and a rigorous empirical technique have been applied.

Managerial implications

Trust in e-commerce is directly affected by the level of satisfaction and web site characteristics like service quality, security and privacy policies and warranty and indirectly through the influence of web site characteristics on e-satisfaction. On the one hand, public institutions can try (and they do) to make consumers of all ages involve in using Internet with public initiatives such as Avanz@ in Spain (www.planavanza.es). Training can erase some differences in online shopping due to the higher lack of experience of females in comparison with males as in the year when we collected the information (there were less female Internet users than males; ONTSI 2009). Besides, it is important that consumers increase their online shopping and that e-vendors satisfy their expectations as satisfaction leads to trust in online contexts, both for males and females. But, how can e-vendors achieve online buyer satisfaction and trust?

E-vendors can use certain characteristics of their web sites to signal quality and help consumers to make the selection decision and solve their adverse selection problem. The assessment of this experience in the electronic context depends on the buyer gender. Males place less importance on relational aspects (e.g. trust), they emphasize outcome-based shopping process (e.g. satisfaction). Therefore, e-vendors should give priority to the incorporation of systems on their web sites that guarantee privacy and security in the purchase process because it directly affects e-trust (in the case of females) or indirectly impact e-trust through satisfaction (in the case of males). Warranty is especially aimed at gaining consumer satisfaction and trust in e-commerce and it is a tool that affects males more than females. Therefore, when addressing females, it is important to place more emphasis on security in the transaction, providing clear cues to reduce risk: information about products and services, indicators of safe connections (such as httpS), security certificates (such as VeriSign), easy and reliable forms of payment (in addition to credit cards, bank transfer, PayPal or payment on delivery), etc. In contract, when addressing males, e-vendors should focus on offering warranty conditions and returning the product.

In short, companies that sell online should carry out studies on the transmission of credible signals through their web sites and prepare suitable gender-based signaling strategies in accordance with the target population. Service quality should be good enough both for males and females as all consumers give high importance to it, maybe because it comprises more general aspects of the online shopping experience and it is more referred to the shopping when consumers have experienced it. From a practical standpoint, it seems advisable to create attractive and usable web sites in order to offer a favourable atmosphere and a satisfactory shopping experience, both for males and females. Online stores should make easy and clear the processes of choosing products or services and paying and showing in every moment the final price (shipping and delivery costs included) and the return and refund policy.

Limitations of the study

Firstly, the information is limited to Spain, which places constraints on any generalization of the model to other geographic and cultural spaces. A further limitation arises from the fact that the greater part of the sample population have a university qualification. Various authors have confirmed that gender differences are not so pronounced in this segment of the population (Zhou et al. 2007); a view that is now widely accepted. This is because of the simple reason that, as the penetration and the diffusion of ICT increase, the moderating effects of gender diminishes. The deepest penetration and diffusion of ICT is precisely among people with university qualifications (the typical Internet user holds at least one university qualification, ONTSI 2009). Regarding limitations of the studied variables, our study is limited since the relational aspects of warranties are not studied. In addition, we have not contemplated the differences in the level of online shopping experience of our sample. However, most of the sample has only a moderated experience in online shopping. Finally, there are other important signals that web sites emanate that have not been included in this study, but that could be contemplated in future studies (e.g., the perceived cost of building and maintaining the site or web site design) (Kirmani and Rao 2000; Montoya-Weiss et al. 2003; Lee and Lin 2005).

Further research

As for the variables under study, one suggestion is to analyze the moderating role of other demographic variables such as educational level that has a global moderating effect, of contextual variables such as the level of experience with online buying, of involvement, familiarity, experience and cultural or moral values. Besides, it would be interesting to look for different results when a multidimensional trust scale (McKnight et al. 2002) or/and the relational aspect of warranty are included (Ostrom and Iacobucci 1998). Likewise, further research could also address the study of the moderating role of gender on signals that affect behavioral variables such as perceived risk and loyalty. Lastly, the belonging of the online buyer to social networks could make a difference in our results (Hoadley et al. 2010).

Notes

The different products or service mentioned by our sample are: entertainment, books, music, TV and movies (36.1%), travel (19.1%), services of e-bank or insurance (9.4%), information technology equipment (9.7%), clothes (5.4%), education (5%), journals (4%), gifts (5.2), electrical appliances (3.2%), food (2.5%) and others (0.4%). Although it was foreseeable that consumers would choose their preferred web sites which they already trusted and with which they were satisfied (thereby reducing the scale variation), it should be taken into account that respondents had to be online shoppers, which is why this data collection method was selected.

A chi-square test shows no significant differences between the profile of our sample and the profile according to information provided by the Spanish Association of E-Commerce [(Gender: χ2 = 4.0, d.f. = 3, p = 0.261); (Age: χ2 = 30.0, d.f. = 25, p = 0.224); (Educational level: χ2 = 20.0, d.f. = 16, p = 0.220)].

References

Anderson, E., & Weitz, B. (1992). The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. Journal of Marketing Research, 29, 18–34.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice. A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Archer, J. (1996). Sex differences in social behavior: Are social role and evolutionary explanations compatible? American Psychologist, 51, 909–917.

Bagozzi, R. P., Baumgartner, H. (1994). The evaluation of structural equation models and hypothesis AM testing. In Principles of marketing research (pp. 386–419). Basil Blackwell.

Bagwell, K., & Ramey, G. (1988). Advertising and limit pricing. Rand Journal of Economics, 19, 59–71.

Baker, E. W., Al-Gahtani, S. S., & Hubona, G. S. (2007). The effects of gender and age on new technology implementation in a developing country. Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Information Technology & People, 20, 352–375.

Bart, Y., Shankar, V., Sultan, F., & Urban, G. L. (2005). Are the drivers and role of online trust the same for all Web sites and consumers? A large—Scale Exploratory empirical study. Journal of Marketing, 69, 133–153.

Bartel-Sheehan, K. (1999). An investigation of gender differences in on-line privacy concerns and resultant behaviors. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 13, 24–38.

Batra, R., & Sinha, I. (2000). Consumer-level factors moderating the success of private label brands. Journal of Retailing, 76, 175–191.

Baumgartner, H., & Homburg, C. (1996). Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13, 139–161.

Bearden, W. O., & Shimp, T. A. (1982). The use of extrinsic cues to facilitate product adoption. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 229–239.

Belanger, F., Hiller, J. S., & Smith, W. J. (2002). Trustworthiness in electronic commerce: The role of privacy, security, and site attributes. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11, 245–270.

Bennett, R., Härtel, C. R., & McColl Kenenedy, J. R. (2005). Experience as a moderator of involvement and satisfaction on brand loyalty in a business-to-business setting 02-314R. Industrial Marketing Management, 34, 97–107.

Birn, R. J. (Ed.). (2000). The handbook of international market research techniques (2nd ed.). London: Kogan Page.

Biswas, D., & Biswas, A. (2004). The diagnostic role of signals in the context of perceived risks in online shopping. Do signals matter more on the Web? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18, 30–45.

Bonn, M. A., Furr, H. L., & Susskind, A. M. (1998). Using the Internet as a pleasure travel planning tool. An examination of the sociodemographic and behavioural characteristics among Internet users and nonusers. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 22, 303–317.

Burke, R. R. (2002). Technology and the customer interface. What consumers want in the physical and virtual store. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30, 411–432.

Chang, J., & Samuel, N. (2004). Internet shopper demographics and buying behaviour in Australia. Journal of the Academy of Business, 5, 171–176.

Chen, Y. L., & Chiu, H. C. (2009). The effects of relational bonds on online customer satisfaction. The Service Industries Journal, 29, 1581–1595.

Chin, W. W. (1995). Partial Least Squares is to LISREL as principal components analysis is to common factor analysis. Technology Studies, 2, 315–319.

Chung, K., & Shin, J. (2010). The antecedents and consequents of relationship quality in Internet shopping. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 22, 473–491.

Citrin, A. V., Stem, D. E., Spangenberg, E. R., & Clark, M. J. (2003). Consumer need for tactile input. An internet retailing challenge. Journal of Business Research, 56, 915–922.

Corbitt, B. J., Thanasankit, T., & Yi, H. (2003). Trust and e-commerce. A study of consumer perceptions. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 2, 203–215.

Dawson, S., Bloch, P. H., & Ridgway, N. (1990). Shopping motives, emotional states, and retail outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 66, 408–427.

Deaux, K. (1984). From individual differences to social categories: Analysis of a decade’s research on gender. American Psychologist, 39, 105–116.

Doney, P. M., & Cannon, J. P. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61, 35–51.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavoir: A social role interpretation. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Emons, W. (1988). Warranties, moral hazard, and the lemons problem. Journal of Economic Theory, 46, 16–33.

Featherman, M., Miyazaki, A., & Sprott, D. (2010). Reducing online privacy risk to facilitate e-service adoption: The influence of perceived ease of use and corporate credibility. Journal of Services Marketing, 23, 219–229.

Feinberg, R., & Kadam, R. (2002). E-CRM web service attributes as determinants of customer satisfaction with retail web sites. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 13, 432–451.

Fiore, S. G. (2002). Designing online experience through consideration of the salient sensory attributes of products. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. UMIST, U.K.

Floh, A., & Treiblmaier, H. (2006). What keeps the banking customer loyal? A Multigroup analysis of the moderating role of consumer characteristic on e-loyalty in the service industry. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 7, 97–110.

Fornell, C. (1982). A second generation of multivariate analysis. New York: Praeger.

Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 58(1994), 1–19.

Garbarino, E., & Strahilevitz, M. (2004). Gender differences in the perceived risk of buying online and the effects of receiving a site recommendation. Journal of Business Research, 57, 768–775.

Gattiker, U. E., Perlusz, S., & Bohmann, K. (2000). Using the internet for B2B activities: A review and future directions for research. Internet research. Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 10, 126–140.

Gefen, D. (2000). E-commerce: The role of familiarity and trust. International Journal of Management Science, 28, 725–737.

Gentry, J. W., Commuri, S., & Jun, S. (2003). Review of literature on gender in the family. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1, 1–18.

Gerrig, R. J., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2002). Glossary of psychological terms. Psychology and life (16th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Gilbert, F. W., & Warren, W. E. (1995). Psychographic constructs and demographic segments. Psychology and Marketing, 12, 223–237.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press.

Gilly, M. C., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1985). The elderly consumer and adoption of technologies. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 353–357.

Goldsmith, R. E., & Flynn, L. R. (2004). Psychological and behavioural drivers of online clothing purchase. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 8, 25–40.

Gummerus, J., Liljander, V., Pura, M., & Van Riel, A. (2004). Customer loyalty to content-based Web sites: The case of an online health-care service. Journal of Services Marketing, 18, 175–186.

Ha, H. Y. (2004). Factors influencing consumer perceptions of brand trust online. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 13, 329–342.

Harris, L. C., & Goode, M. M. H. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust. A study of on-line service dynamics. Journal of Retailing, 80, 139–158.

Hawes, J. M., & Lumpkin, J. R. (1986). Perceived risk and the selection of a retail patronage mode. Journal of Academy of Marketing Science, 14, 37–42.

Helgesen, O., & Nesset, E. (2010). Gender, store satisfaction and antecedents: A case study of a grocery store. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 27, 114–126.

Hernández, B., Jiménez, J., Martín, J. (2010) Age, gender and income: do they really moderate online shopping behaviour? Online Information Review, 35.

Hoadley, C. M., Xu, H., Lee, J. J., & Rosson, M. B. (2010). Privacy as information access and illusory control: The case of the Facebook News Feed privacy outcry. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 9(1), 50–60.

Homburg, C., & Giering, A. (2001). Personal characteristics as moderators of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty—an empirical analysis. Psychology and Marketing, 18, 43–66.

Homburg, C., Giering, A., Menon, A. (2003). Relationship characteristics as moderators of the satisfaction-loyalty link: Findings in a business-to-business context. Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 35–62

Hwang, Y. (2009). The impact of uncertainty avoidance, social norms and innovativeness on trust and ease of use in electronic customer relationship management. Electronic Markets, 19, 89–98.

Iacobucci, D., & Ostrom, A. L. (1993). Gender differences in the impact of ‘core’ and ‘relational’ aspects of services on the evaluation of service encounters. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2, 257–286.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL VIII: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago: Scientific Software International.

Karande, K., Magnini, V. P., & Tam, L. (2007). Recovery voice and satisfaction after service failure: An experimental investigation of mediating and Moderating Factors. Journal of Service Research, 2007(10), 187–203.

Kassim, N. M., & Abdullah, N. (2010). The effect of perceived service quality dimensions on customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty in e-commerce settings. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 22, 351–371.

Kirmani, A., & Rao, A. R. (2000). No pain, no gain: A critical review of the literature on signaling unobservable product quality. Journal of Marketing, 64, 66–79.

Kolsaker, A., & Payne, C. (2002). Engendering trust in ecommerce. A study of gender-based concerns. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 20, 206–614.

Lau, G. T., & Lee, S. H. (1999). Consumers’ trust in a brand and the link to brand loyalty. Journal of Market-Focused Management, 4, 341–370.

Lee, B., Ang, L., & Dubelaarc, C. (2005). Lemons on the Web. A signalling approach to the problem of trust in Internet commerce. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26, 607–623.

Lee, E. J., & Overby, J. W. (2004). Creating value for online shoppers: Implications for satisfaction and loyalty. Journal of Consumer Satisfaction and Complaining Behavior, 17, 54–67.

Lee, G. G., & Lin, H. F. (2005). Customer perceptions of e-service quality in online shopping. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 33, 161–176.

Lichtenstein, S., & Williamson, K. (2006). Understanding consumer adoption of internet banking. An interpretive study in the Australian banking context. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 7, 50–66.

Loomba, A. (1998). Evolution of product warranty: A chronological study. Journal of Management History, 4, 124–136.

Luo, J. T., McGoldrick, P., Beatty, S., & Kathleen, A. K. (2006). On-screen characters. Their design and influence on consumer trust. The Journal of Services Marketing. Santa Barbara, 20, 112–124.

Maditinos, D., & Theodoridis, K. (2010). Satisfaction determinants in the Greek on-line shopping context. Information Technology and People, 23, 312–329.

McKnight, A., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). Developing and validating trust measures for e-Commerce: An integrative typology. Information Systems Research, 13, 334–359.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resources Management Review, 1, 61–98.

Mittal, V., & Kamakura, W. A. (2001). Satisfaction, repurchase intent and repurchase behavior. Investigating the moderating effect of customer characteristics. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 131–142.

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993). Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57, 81–101.

Montoya-Weiss, M. M., Voss, G. B., & Grewal, D. (2003). Determinants of online channel use and overall satisfaction with a relational, multichannel service provider. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31, 448–458.

Morgan, R., & Hunt, S. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58, 20–38.

National Institute of Statistics (INE) (2009). Survey about equipment and information and communication Technologies (TIC), retrieved from http.//www.ine.es/prensa/tich_prensa.htm.

Ndubisi, N. O. (2006). Effect of gender on customer loyalty. A relationship marketing approach. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 24, 48–61.

Nelson, P. (1974). Advertising as information. Journal of Political Economy, 82, 729–754.

Noble, S. M., Griffith, D. A., & Adjei, M. T. (2006). Drivers of local merchant loyalty: Understanding the influence of gender and shopping motives. Journal of Retailing, 82, 177–188.

Nooteboom, B., Berger, H., & Noorderhaven, N. (1997). Effects of trust and governance on relational risk. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 308–338.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17, 460–469.

O’Neil, D. (2001). Analysis of internet users’ level of online privacy concerns. Social Science Computer Review, 19, 17–31.

ONTSI. (2009). Study about electronic commerce B2C 2009. Observatory of telecommunication and Information Society, Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Tourism.

Ostrom, A. L., & Iacobucci, D. (1998). The effect of guarantees on consumers’ evaluation of services. Journal of Service Marketing, 12, 362–378.

Park, C. H., & Kim, Y. G. (2003). Identifying key factors affecting consumer purchase behaviour in an online shopping context. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 31, 16–29.

Park, C. H., & Kim, Y. G. (2006). The effect of information satisfaction and relational benefit on consumers’ online shopping site commitments. Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations, 4, 70–90.

Park, J., & Stoel, L. (2005). Effect of brand familiarity experience and information on online apparel purchase. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 33, 148–160.

Qin, S., Zhao, L., & Yi, X. (2009). Impacts of customer service on relationship quality: An empirical study in China. Managing Service Quality, 19, 391–409.

Ranaweera, C., McDougall, G., & Bansal, H. (2005). A model of on-line customer behavior during the initial transaction. Moderating effects of customer characteristics. Marketing Theory, 5, 51–74.

Rao, A. R., Qu, L., & Ruekert, R. W. (1999). Signaling unobservable product quality through a brand ally. Journal of Marketing Research, 36, 258–268.

Ravald, A., & Grönroos, C. (1996). The value concept and relationship marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 30, 19–30.

Reinartz, W., Haenlein, M., & Henseler, J. (2009). An empirical comparison of the efficacy of covariance-based and variance-based SEM. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26, 332–344.

Ribbink, D., Van Riel, A. C. R., Liljander, V., & Streukens, S. (2004). Comfort your online customer. Quality, trust, royalty on the Internet. Managing Service Quality, 14, 446–456.

Rierdan, J., Koff, E., & Heller, H. (1982). Gender, anxiety, and human figure drawings. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46, 594–596.

Rodgers, S., & Harris, M. A. (2003). Gender and e-commerce. An exploratory study. Journal of Advertising Research, 43, 322–329.

Roehl, W. (2001) Browsing, searching, and purchasing travel products on-line. In N. Moisey, N. Nickerson and K. L. Andreck (Eds.), 32nd Annual TTRA Conference Proceedings. Fort Myers, USA.

Roy, M., Dewit, O., & Aubert, B. (2001). The impact of interface usability on trust in Web retailers. Internet Research: Electronic Networking Applications and Policy, 11, 388–398.

Ruparelia, N., White, L., & Hughes, K. (2010). Drivers of brand trust in Internet retailing. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 19, 250–260.

San-Martín, S., & Camarero, C. (2008). Consumer trust to a web site: Moderating effect of attitudes toward online shopping. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11, 549–554.

Shemwell, D. J., Cronin, J. J., & Bullard, W. R. (1994). Relational exchange in services: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 5, 57–68.

Selnes, F. (1998). Antecedents and consequences of trust and satisfaction in buyer-seller relationships. European Journal of Marketing, 32, 305–322.

Shankar, V., Urban, G., & Sultan, F. (2002). Online trust. A stakeholder perspective, concepts, implications, and future directions. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11, 325–344.

Sidin, S. M., Zawawi, D., Yee, W. F., Busu, R., & Hamzah, Z. L. (2004). The effects of sex role orientation on family purchase decision making in Malaysia. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21, 381–390.

Slama, M. E., & Tashlian, A. (1985). Selected socioeconomic and demographic characteristics associated with purchasing involvement. Journal of Marketing, 49, 72–82.

Smith, F. M. (1998). Between East and West: Sites of resistance in East German youth cultures. In T. Skelton & G. Valentine (Eds.), Cool places: Geographies of youth cultures (pp. 289–304). London: Routledge.

Singh, M. (2002). E-services and their role in B2C e-commerce. Managing Service Quality, 12, 434–446.

Singh, J., & Sirdeshmukh, D. (2000). Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer satisfaction and loyalty judgments. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28, 150–167.

Sun, H., & Zhang, P. (2006). The role of moderating factors in user technology acceptance. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 64, 53–78.

Szymanski, D. M., & Hise, R. T. (2000). E-satisfaction. An initial examination. Journal of Retailing, 76, 309–322.

Tamimi, N., & Sebastianelli, R. (2007). Understanding eTrust. Journal of Information Privacy & Security, 3, 3–17.

Tan, S. J. (1999). Strategies for reducing consumers’ risk aversion in Internet shopping. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 16, 163–180.

Teas, R. K., & Agarwal, S. (2000). The effects of extrinsic product cues on consumer’s perceptions of quality. Sacrifice and Value, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28, 278–290.

Trocchia, P. J., & Janda, S. (2003). How do consumers evaluate Internet retail service quality? The Journal of Service Marketing, 17, 243–253.

Vrechopoulos, A. P., O’Keefe, R. M., Doukidis, G. I., & Siomkos, G. J. (2004). Virtual store layout. an experimental comparison in the context of grocery retail. Journal of Retailing, 80, 13–22.

Wang, S., Beatty, S. E., & Foxx, W. (2004). Signaling the trustworthiness of small online retailers. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18, 53–69.

Williams, T. G. (2002). Social class influences on purchase evaluation criteria. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 19, 249–276.

Wolfinbarger, M., & Gilly, M. C. (2003). E-TailQ: Dimensionalizing, measuring and predicting e-tail quality. Journal of Retailing, 79, 183–198.

Wood, S. L. (2000). Remote purchase environments. The influence of return policy leniency on two-stage decision process. Journal of Marketing Research, 38, 157–169.

Yadav, M. S., & Varadarajan, R. (2005). Understanding product migration to the electronic marketplace. A conceptual framework. Journal of Retailing, 81, 125–140.

Yalch, R., & Spangenberg, E. (1990). Effects of store music on shopping behavior. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 7, 55–63.

Yoon, S. J., & Kim, S. (2009). Developing the causal model of online store success. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 19, 265–284.

Yoon, S. J. (2002). The antecedents and consequences of trust in online-purchase decisions. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 16, 47–63.

Yousafzai, S. Y., Pallister, J. G., & Foxall, G. R. (2005). Strategies for building and communicating trust in electronic banking: A field experiment. Psychology & Marketing, 22, 181–201.

Zhang, X., Prybutok, V. R., & Strutton, D. (2007). Modeling influences on impulse purchasing behaviours during online marketing transaction. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 15, 79–89.

Zhou, L., Dai, L., & Zhang, D. (2007). Online shopping acceptance model—A critical survey of consumer factors in online shopping. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 8, 41–62.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the support by Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (Spain) to a research project on online buying and selling (reference SEJ 2007–63378).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Hans-Dieter Zimmermann

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

San Martín, S., Jiménez, N.H. Online buying perceptions in Spain: can gender make a difference?. Electron Markets 21, 267–281 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-011-0074-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-011-0074-y