Abstract

The study examined unique trajectories of ADHD severity from childhood (7–16 yo at baseline) through adulthood in a sample of ADHD, bipolar and healthy subjects. Comorbid disorders and temperament were examined as correlates of course of ADHD. N = 81 participants with an ADHD diagnosis, ascertained as a comparison group in a study of bipolar disorder (BP-I), were followed over a 10-year period. Growth mixture modeling (GMM) of ADHD severity was used to investigate trajectories of ADHD severity over 10 years. GMM revealed four trajectories in the N = 251 participants included in these analyses. A persisting high ADHD trajectory had the highest rates of comorbid major depressive disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. This persisting high ADHD group also had higher fantasy and lower persistence and self-directedness compared with those who displayed a pattern of decreasing ADHD symptoms over time. Psychopathologic features that characterize divergent trajectories of ADHD into adulthood are elucidated, and additional, larger studies are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In about 40–80 % of children with ADHD, the disorder is chronic and continues into adolescence (Barkley 2006; Barkley et al. 1990; Brown and Borden 1986; Hill and Schoener 1996; Wender 1995; Wilens et al. 2002; Wilson and Marcotte 1996). Despite being highly informative regarding course of ADHD, early longitudinal studies of ADHD into adulthood (including the Milwaukee Study, the New York Study, the Swedish study, and the Montreal Study) report wide ranges of rates of adult ADHD, likely related to methodological challenges (Barkley et al. 2002a; Mannuzza et al. 1993, 1998; Rasmussen and Gillberg 2000; Weiss et al. 1985). This wide range has been attributed to attrition of participants, use of different informants, use of varied diagnostic criteria, and a variation in methods of assessment and ascertainment (e.g., asking about persistence of symptoms vs. current diagnostic status, use of self-ratings vs. observations) (Faraone et al. 2006; Mannuzza et al. 2003). Most recent longitudinal studies of ADHD into adulthood suggest symptoms persist in approximately 66 % of cases (Uchida et al. 2015; Karam et al. 2015). ADHD continues to be described as a lifespan disorder in a majority of studies (Barkley 2006; Halperin and Healey 2011; Spencer et al. 2007; Turgay et al. 2012), though a recent, unreplicated longitudinal investigation suggests that childhood and adulthood ADHD may be different disorders with different etiologies (Moffitt et al. 2015).

A number of longitudinal investigations about childhood ADHD have informed persistence, but not without limitations. Empirical studies have underscored the importance of comorbid and early childhood conduct problems as a significant predictor of persistence of ADHD through adolescence (Gittelman et al. 1985; Hart et al. 1995; Lahey et al. 2000; Loney et al. 1981; Taylor et al. 1991). In addition to psychiatric comorbidity, Rutter’s adversity indicators (such as family size and conflict, paternal criminality, social status and maternal psychopathology) have been suggested to contribute to ADHD persistence into adolescence (Biederman et al. 1992, 1995). An 11-year follow-up study also suggested that persistence was related not only to comorbidity of conduct, mood, and anxiety disorders, but also to ADHD impairment at baseline and exposure to maternal psychopathology; however, the study combined adolescent and adult outcomes (participants were 15–31 yo at follow-up) making it difficult to disentangle outcomes specific to adulthood (Biederman et al. 2011). Another study combining adolescent and adult outcomes of ADHD suggested that IQ and socioeconomic status (SES) acted as moderators of ADHD persistence (Cheung et al. 2015). In addition to combining outcomes of adolescence and adulthood, longitudinal investigations of ADHD into adulthood include use of referred populations, limiting generalizability to less severe populations (Biederman et al. 2010b). Furthermore, many past samples have focused exclusively on males, and only more recently included a focus on females (Biederman et al. 2010a; Hinshaw et al. 2012; Monuteaux et al. 2010).

What remains under investigated is which factors characterize individuals with ADHD who will remit or resolve with development versus experience a chronic and persistent course into adulthood (Karam et al. 2015; Lara et al. 2009; Nigg et al. 2002). A number of longitudinal studies of ADHD have tracked outcomes over 10 years, but there has been less focus on temperament and other features of participants that might contribute to persistent course (Barkley et al. 2002b; Mannuzza et al. 1993, 1998, 2003; Pingault et al. 2011; Rasmussen and Gillberg 2000; Weiss et al. 1985). This is important to elucidate because personality factors including low agreeableness and high neuroticism have been associated with persistent ADHD (Miller et al. 2008). Studies distinguishing key factors that characterize persistence versus remission of ADHD into adulthood are still needed (Barkley et al. 2008; Halperin et al. 2008). The present study benefits from low attrition of participants with ADHD over a 10-year course into adulthood. Understanding how to distinguish these groups is important to determine who are in need of early and ongoing intervention versus those more likely to have symptoms that resolve with development.

The current study capitalized on a large 10-year longitudinal dataset that tracked ADHD severity in participants with ADHD alone and in those with a bipolar phenotype with comorbid ADHD (as well as healthy controls) from childhood into adulthood. The aim was to investigate trajectories of ADHD severity across development and investigate factors that characterized the variation in the longitudinal course of ADHD into adulthood using growth mixture modeling, while carefully controlling for bipolar comorbidity. Personality factors and substance use disorders (SUD) were included given their established relationship to ADHD (Miller et al. 2008; Molina et al. 2009; Wilens and Upadhyaya 2007).

Methods

Participants

N = 268 participants ages 7–16 at baseline were comprehensively assessed using the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) as part of the longitudinal Phenomenology and Course of Pediatric BP-I study (Geller, PI MH-53063). Inclusion criteria for all participants at baseline were 7–16 years of age, males and females, and good physical health. Exclusion criteria were IQ < 70, epilepsy or other major medical or neurological disorders, pervasive developmental disorders, schizophrenia, baseline substance dependency, and pregnancy. Participants who developed SUD or became pregnant after baseline were retained in the study. Additional details of and rationale for study inclusion/exclusion criteria have been previously reported (Geller et al. 2004). Participants were comprehensively assessed (see measures below) every 2 years for a 10- or 12-year period, as detailed in Table 1. The study ended mid-way through data collection at the 12-year wave.

ADHD participants, like BP-I participants, were consecutively ascertained from outpatient pediatric and psychiatric clinics. Screenings for exclusion criteria for all new consecutive cases were conducted by non-blind research nurses who were different than the blinded nurses who conducted in-laboratory psychiatric assessment once telephone screenings occurred. Healthy control participants were obtained through a random survey that matched them to BP-I participants by age, gender, SES, ethnicity, and zip code. The Human Studies Committee at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis approved the study.

There were N = 81 participants in the ADHD group at baseline. These participants met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD (with hyperactivity, i.e., hyperactive/impulsive subtype [H] or combined type [C], not inattentive type [I]) at baseline without mood comorbidity and were clinically impaired, as evidenced by a CGAS score of ≤60. ADHD participants were required to have onset of ADHD symptoms prior to age 7 and duration greater than or equal to 6 months. ADHD-H and ADHD-C, but not ADHD-I, were included as a psychiatric comparison group (given focused study goals). ADHD-I was an exclusion for the ADHD group at baseline and was not an exclusion for the BP-I group at baseline; however, there was only n = 1 BP-I subjects with ADHD-I at baseline. Children in the ADHD group could not have BP-I or MDD (based on original study aims), but could have conduct disorder (CD) and/or oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), given their common comorbidity with ADHD in children. ADHD participants could have BP-I and/or MDD at follow-up.

There were N = 93 participants in the BP-I group at baseline. Child BP-I participants in this study were required to have elated mood and/or grandiosity as one of the mania criteria. Because high rates of ADHD comorbidity have been observed in child BP-I disorder, an ADHD diagnosis was not exclusionary in the BP-I group. These participants had a Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) (Bird et al. 1987; Shaffer et al. 1983) score of ≤60, signifying definite clinical impairment.

There were N = 94 healthy control participants at baseline. Healthy control subjects were required to not have BP-I, MDD, or ADHD at baseline. It was found that no healthy control subjects had any Axis I disorders at baseline.

Measures

Diagnostic Assessment The WASH-U-KSADS (Geller et al. 1996) is a semi-structured interview that was administered by experienced research clinicians to mothers about their children and to children about themselves. It was developed from the KSADS (Puig-Antich and Ryan 1986) by adding onset and offset of lifetime and current symptoms for DSM-IV diagnoses. The WASH-U-KSADS has established validity (Geller et al. 1998, 2001). To score the WASH-U-KSADS, child and parent responses were combined by using the most severe rating, in accordance with the methods described by Bird et al. (1992). Of note, the correlation between combined parent and child report and parent-only report of number of baseline ADHD symptoms was 0.97. This is consistent with children under-reporting ADHD symptoms. Combined parent and child report was therefore not separated in the analyses. Teacher ratings were not addressed in the current study as they were inconsistently available. All research materials, including school reports and separate videotapes of mothers and children, were reviewed in consensus conference with research nurses and a senior clinician. Raters were blind to group status at baseline assessment. Clinicians were trained to inter-rater reliability (kappa = 0.82–1.00) and recalibrated yearly (Geller et al. 2001).

Personality: temperament and character The Junior Temperament and Character Inventory (JTCI) measures four temperament and four character traits of children. Temperament traits include novelty-seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence. Character traits include self-directedness, cooperativeness, fantasy, and spirituality. The JTCI is made up of 108 true/false items to assess children’s behaviors, opinions, and feelings (Luby et al. 1999). Temperament traits are considered relatively stable after the preschool years, though dynamic processes with the environment continue (Roberts and DelVecchio 2000; Shiner et al. 2012). The JTCI was administered at the 2-year follow-up separately to children and their parents. Data from the two informants was combined (after reverse scoring negatively phrased items) by considering any items endorsed as true by either informant as true.

Global functioning The CGAS measures severity based on global impairment from psychiatric symptoms and related adaptation in psychosocial functioning in school, social, work, and family contexts. On this scale, 0 is worst, 100 is best, and ≤60 is definite clinical impairment. The CGAS score is the lowest level of functioning during the rating period.

SES was established from the Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Social Status (Hollingshead 1976).

Substance use disorders (SUD) were defined using DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria including for alcohol, marijuana, and other illicit drug use (e.g., sedatives, opioids, cocaine, other). A subset of N = 155 participants were assessed as adults approximately three and a half years after the original study was completed. SUD was assessed at this time with the NetSCID (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders).

Statistical analysis

Growth mixture modeling (GMM) in Mplus version 7.3 was used to group participants into subgroups based on ADHD severity scores across the longitudinal course of the study. Specifically, an ADHD severity score was calculated at each of the six waves (baseline through 10-year follow-up) as the number of ADHD symptoms endorsed at each wave (maximum of 18). A quadratic growth mixture model with these six severity scores as the outcome variables was used to determine a categorical latent class variable for grouping participants with similar ADHD severity trajectories. Mania severity was calculated as the number of mania symptoms endorsed at each wave (maximum of 8) and was included in the model as a time-varying covariate. Baseline age and gender were also included as covariates in the growth mixture model. Each subject’s probability of belonging to each of the latent classes was evaluated, and participants were assigned to the latent class with the greatest probability.

N = 17 participants were not included in the analysis because they dropped out of the study, so GMM was conducted on N = 251 of the original N = 268 participants. Several growth mixture models with varying numbers of classes for the latent class variable were compared, and the best model according to the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test was selected.

Once latent class assignment was complete, baseline demographic and diagnostic characteristics were compared across classes using post hoc linear regression for continuous variables and logistic regression for categorical variables.

Psychiatric diagnoses through the 10-year follow-up, adult SUD, and temperament and character factors obtained at the 2-year follow-up were compared across classes using post hoc logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes and linear regression for continuous outcomes. These models included baseline age, SES, gender, race, baseline mania, and use of stimulants or other medication for ADHD at any time during the study as covariates. Contrast statements were included in these models to make pairwise comparisons of the classes. Bonferroni correction was used to account for the six pairwise class comparisons, resulting in a significant p value of p < 0.0083. All analyses other than GMM were completed in SAS version 9.3.

Results

Of the N = 268 baseline study participants, N = 17 (6.3 %) dropped out (N = 6 ADHD, N = 9 BP-I, N = 2 healthy controls) through the 10-year assessment. The only missed assessments were those occurring after a subject discontinued from the study by design, i.e., no subject missed an assessment but was then assessed at a later data collection wave. As previously noted, the N = 17 participants who discontinued the study were not included in these analyses. At baseline, 87.1 % of the N = 93 BP-I subjects had comorbid ADHD.

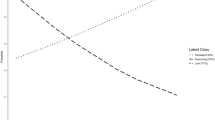

Fit statistics for growth mixture models with latent class variables with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 classes were compared. The BIC was lowest in the 4-class model (BIC = 8158.8) compared to the others (1-class BIC = 17129.3, 2-class BIC = 8579.6, 3-class BIC = 8253.0, 5-class BIC = 8235.9). The 4-class model also fit significantly better than the 3-class model according to the Lo–Mendell–Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (p = 0.0037), while the 5-class model was not a significant improvement over the 4-class model (p = 0.4727). Therefore, the model that best fit the data included a latent class variable with four classes; one of these had significant intercept, linear, and quadratic components, and the other three classes had significant intercepts and linear components. Details of the growth mixture model with four latent classes are shown in Table 2. There were N = 251 total participants: N = 96 in class 1 (persisting low), N = 39 in class 2 (quickly remitting), N = 60 in class 3 (gradually remitting), and N = 56 in class 4 (persisting high). Figure 1 illustrates the trajectories of ADHD severity scores in the four latent classes.

Baseline demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the N = 251 participants by latent class are shown in Table 3. Participants in the persistently high class were significantly younger than participants in all three other classes. Also, subjects in the gradually remitting class were significantly younger than quickly remitting subjects. In addition, there were more males in the gradually remitting and persisting high classes compared to the persisting low and quickly remitting classes. The racial breakdown of the gradually remitting class was significantly different than those of the persisting low and persisting high classes, with fewer white subjects and more black and other race subjects. There were no differences in SES. Baseline CGAS scores were higher, and mania and ADHD severity were significantly lower in the persisting low class compared to the other three classes. Additionally, baseline ADHD severity was significantly lower in the quickly remitting class compared to the gradually remitting and persisting high classes. All N = 92 baseline healthy control participants were in the persisting low class. Rate of stimulant use was significantly lower in the persisting low class compared to the three other classes, and participants in the quickly remitting class used stimulants significantly less than participants in the persisting high class.

Table 4 shows psychiatric diagnoses through 10-year follow-up, adult SUD, and temperament and character factors by latent class. Comorbid disorders were considered anytime through 10-year follow-up, and temperament assessments took place 2 years after baseline. They were correlates of course. In general, the persisting low class had the least psychopathology. Because this class contained primarily baseline healthy controls who remained consistently healthy over the 10 years of study, comparisons of interest are those between the quickly remitting, gradually remitting, and persisting high latent classes.

The persisting high class had significantly higher rates of MDD and ODD than the gradually remitting class and higher rates of MDD than the quickly remitting class. Rates of mania and social phobia were higher in the persisting high class compared with the gradually remitting class, but significance did not remain after Bonferroni correction. Similarly, the persisting high class had higher rates of panic attack than the quickly remitting class, but these results did not hold up to correction for multiple comparisons. The persisting high class had the highest rate of SUD in adulthood (60 %), although this rate was not significantly greater than the rates in the other classes (PL: 19.4 %, QR: 18.5 %, GR: 36.4 %). There were no significant differences in rates of alcohol use disorder or cannabis use disorder. However, the persisting high class had marginally higher rates of both alcohol and marijuana use than the quickly remitting class and marginally higher rates of cannabis use disorder than the gradually remitting class.

Temperament and character differences were evident between the quickly remitting and persisting high classes, with the persisting high class having less persistence, less self- directedness, and more fantasy.

Discussion

Study findings elucidate key psychopathological features that characterize severe trajectories of ADHD that persist into adulthood. A persisting high ADHD trajectory had the highest rates of comorbid major depressive disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. These findings are in line with a number of studies finding comorbid psychopathology among persisting cases of ADHD in both clinical and non-clinical samples (Barbaresi et al. 2013; Barkley et al. 2008; Kessler et al. 2011; Lara et al. 2009; Mannuzza et al. 1998). In contrast to other longitudinal studies, CD was not found to be more common in the persisting high class. This may be because of the inclusion of females in the sample and the low prevalence of CD found in the overall sample at baseline (see Geller et al. 2002). The lack of SUD findings may also be related to the low base rate of CD, as CD symptoms are thought to account for the relationship of ADHD and SUD in some larger longitudinal investigations (Lynskey and Fergusson 1995); however, alcohol and cannabis use were marginally significant in the persisting high group compared to the others, suggesting power limitations could also account for the lack of SUD in persistent ADHD.

Importantly, the persisting high ADHD group had less persistence, less self-directedness, and more fantasy on temperament and character measures than the quickly remitting group, whose severity of ADHD diminished into adulthood. It is not altogether surprising that the group characterized by persisting high ADHD had low self-directedness and persistence, as lack of persistence in effortful tasks has been well described in laboratory and actual settings and speculated to be related to motivational and reward sensitivity differences in ADHD (for review, see Barkley 2006; Rettew et al. 2004). Similarly, children with ADHD may be described by teachers as seemingly off-task or fantasizing, though fantasy specifically assessed as a character trait (e.g., tendency to imagine/daydream) in ADHD is not empirically well investigated (Rettew et al. 2004).

Limitations of the study include the secondary analysis of a dataset originally ascertained for the investigation of BP-I; most of the affected subjects at baseline had BP-I as their primary diagnosis, which is a possible confounder. However, the vast majority of the BP-I sample had comorbid ADHD, and mania severity was included as a time-varying covariate in the growth mixture models that determined the ADHD trajectories. Further, baseline BP-I diagnosis was controlled for in statistical comparisons of the ADHD trajectory classes. Given the richness and comprehensive nature of this large longitudinal dataset, the comparison ADHD group and the ADHD severity in the BP group meaningfully informs trajectories of ADHD. Despite the rigorous statistical control, ADHD in the BP-I group could reflect a unique pathology, and this should be considered in future studies. The study did not include the inattentive type of ADHD and study findings are not generalizable to this group. A potential limitation was the use of medications in the sample. However, this was also addressed statistically by covarying for stimulant use. Another limitation is the lack of teacher informed ADHD in children; however, because the study tracked individuals over 10 years, teacher reports became inconsistently available. This is not an uncommon problem in longitudinal studies of ADHD into adulthood and does not minimize the merit of the study in adding to a critical body of literature informing long term clinical outcomes. A recent study suggested teacher reports did not predict persistence of ADHD (Cheung et al. 2015). Finally, the higher SES of the overall sample may limit generalizability to other populations.

Conclusions

Despite the limitations, the present investigation tracked participants over 10 years from middle childhood into early adulthood, informing characteristic trajectories of ADHD severity into adulthood using advanced statistical methodology. Current findings add to the literature on the characteristics of childhood ADHD that persist into adulthood and begin to elucidate what factors may emerge in such a consistently severe group of individuals with ADHD. Findings suggest that key temperament features may be important markers of a persistent course and therefore might be key targets for early intervention. Taken together, findings highlight the need for additional, larger investigations that could shed light on ADHD subjects most at risk of adverse adult outcomes so that limited public health resources can be optimized.

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV), 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK (2013) Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: a prospective study. Pediatrics 131(4):637–644. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2354

Barkley R (2006) Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a handbook for diagnosis and treatment, 3rd edn. NY Guilford Press, New York

Barkley R, DuPaul G, McMurray M (1990) Comprehensive evaluation of attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity as defined by research criteria. J Consult Clin Psychol 58(6):775–789. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.775

Barkley R, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K (2002a) The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 111(2):279–289

Barkley R, Murphy K, Dupaul G, Bush T (2002b) Driving in young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: knowledge, performance, adverse outcomes, and the role of executive functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 8(5):655–672. doi:10.1017/S1355617702801345

Barkley R, Murphy KR, Fischer M (2008) Adult ADHD: what the science says. Guilford, New York

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Benjamin J, Krifcher B, Moore C et al (1992) Further evidence for family-genetic risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Patterns of comorbidity in probands and relatives psychiatrically and pediatrically referred samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49(9):728–738. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820090056010

Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone SV, Kiely K, Guite J, Mick E, Ablon S, Warburton R, Reed E (1995) Family-environment risk factors for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a test of Rutter’s indicators of adversity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 52(6):464–470. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950180050007

Biederman J, Petty C, Monuteaux M, Fried R, Byrne D, Mirto T, Spencer T, Wilens T, Faraone S (2010a) Adult psychiatric outcomes of girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: 11-year follow-up in a longitudinal case–control study. Am J Psychiatry 167(4):409–417. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050736

Biederman J, Petty CR, Evans M, Small J, Faraone SV (2010b) How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Res 177(3):299–304. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.010

Biederman J, Petty CR, Clarke A, Lomedico A, Faraone SV (2011) Predictors of persistent ADHD: an 11-year follow-up study. J Psychiatr Res 45(2):150–155. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.009

Bird H, Canino G, Rubiostipec M, Ribera JC (1987) Further measures of the psychometric properties of the Childrens Global Assessment Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44(9):821–824. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800210069011

Bird H, Gould M, Staghezza B (1992) Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31(1):78–85. doi:10.1097/00004583-199201000-00012

Brown RT, Borden KA (1986) Hyperactivity at adolescence: some misconceptions and new directions. J Clin Child Psychol 15(3):194–209. doi:10.1207/S15374424jccp1503_1

Cheung CH, Rijdijk F, McLoughlin G, Faraone SV, Asherson P, Kuntsi J (2015) Childhood predictors of adolescent and young adult outcome in ADHD. J Psychiatr Res 62:92–100. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.01.011

Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E (2006) The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med 36(2):159–165. doi:10.1017/s003329170500471x

Geller B, William M, Zimerman B, Frazier J (1996) Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS). Washington University in St Louis, St Louis

Geller B, Warner K, Williams M, Zimerman B (1998) Prepubertal and young adolescent bipolarity versus ADHD: assessment and validity using the WASH-U-KSADS, CBCL and TRF. J Affect Disord 51(2):93–100. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(98)00176-1

Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, DelBello MP, Soutullo C (2001) Reliability of the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (WASH-U-KSADS) mania and rapid cycling sections. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(4):450–455. doi:10.1097/00004583-200104000-00014

Geller B, Zimerman B, Williams M, Delbello MP, Bolhofner K, Craney JL, Frazier J, Beringer L, Nickelsburg MJ (2002) DSM-IV mania symptoms in a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype compared to attention-deficit hyperactive and normal controls. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 12(1):11–25. doi:10.1089/10445460252943533

Geller B, Tillman R, Craney JL, Bolhofner K (2004) Four-year prospective outcome and natural history of mania in children with a prepubertal and early adolescent bipolar disorder phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry 61(5):459–467. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.459

Gittelman R, Mannuzza S, Shenker R, Bonagura N (1985) Hyperactive boys almost grown up: I. Psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42(10):937–947. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790330017002

Halperin J, Healey D (2011) The influences of environmental enrichment, cognitive enhancement, and physical exercise on brain development: can we alter the developmental trajectory of ADHD? Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35(3):621–634. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.006

Halperin J, Trampush J, Miller C, Marks D, Newcorn J (2008) Neuropsychological outcome in adolescents/young adults with childhood ADHD: profiles of persisters, remitters and controls. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(9):958–966. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01926.x

Hart E, Lahey B, Loeber R, Applegate B, Frick P (1995) Developmental change in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in boys: a four-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 23(6):729–749. doi:10.1007/BF01447474

Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Zalecki C, Huggins SP, Montenegro-Nevado AJ, Schrodek E, Swanson EN (2012) Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. J Consult Clin Psychol 80(6):1041–1051. doi:10.1037/a0029451

Hollingshead AB (1976) Four Factor Index of social status. Yale University Department of Sociology, New Haven

Karam RG, Breda V, Picon FA, Rovaris DL, Victor MM, Salgado CAI, Caye A (2015) Persistence and remission of ADHD during adulthood: a 7-year clinical follow-up study. Psychol Med 45(10):2045–2056

Kessler RC, Ormel J, Petukhova M, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Russo LJ, Ustun TB (2011) Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68(1):90–100. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.180

Lahey B, McBurnett K, Loeber R (2000) Are attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder developmental precursors to conduct disorder? In: Sameroff A, Lewis M, Miller S (eds) Handbook of developmental psychopathology. Plenum, New York, pp 431–446

Lara C, Fayyad J, de Graaf R, Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Angermeyer M, Demytteneare K, de Girolamo G, Haro JM, Jin R (2009) Childhood predictors of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Biol Psychiatry 65(1):46–54. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.005

Loney J, Kramer J, Milich RS (1981) The hyperactive child grows up: predictors of symptoms, delinquincy and achievement at follow-up. In: Gadow KD, Loney J (eds) Psychosocial aspects of drug treatment for hyperactivity. Westview Press, Boulder, pp 381–416

Luby J, Svrakic D, McCallum K, Przybeck T, Cloninger C (1999) The Junior Temperament and Character Inventory: preliminary validation of a child self-report measure. Psychol Rep 84(3 Pt 2):1127–1138. doi:10.2466/pr0.1999.84.3c.1127

Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM (1995) Childhood conduct problems, attention deficit behaviors, and adolescent alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use. J Abnorm Child Psychol 23(3):281–302. doi:10.1007/BF01447558

Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M (1993) Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50(7):565–576. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820190067007

Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M (1998) Adult psychiatric status of hyperactive boys grown up. Am J Psychiatry 155(4):493–498

Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Moulton JL (2003) Persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adulthood: What have we learned from the prospective follow-up studies? J Atten Disord 7(2):93–100. doi:10.1177/108705470300700203

Miller CJ, Miller SR, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM (2008) Personality characteristics associated with persistent ADHD in late adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36(2):165–173. doi:10.1007/S10802-007-9167-7

Moffitt TE, Houts R, Asherson P, Belsky DW, Corcoran DL, Hammerle M, Poulton R (2015) Is Adult ADHD a Childhood-Onset Neurodevelopmental Disorder? Evidence From a Four-Decade Longitudinal Cohort Study. Am J Psychiatry 172(6):967–977

Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Vitiello B, Jensen PS, Houck PR (2009) The MTA at 8 Years: prospective follow-up of children treated for Combined-Type ADHD in a multisite study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48(5):484–500. doi:10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819c23d0

Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Faraone SV, Biederman J (2010) The influence of sex on the course and psychiatric correlates of ADHD from childhood to adolescence: a longitudinal study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 51(3):233–241. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02152.x

Nigg JT, Butler KM, Huang-Pollock CL, Henderson JM (2002) Inhibitory processes in adults with persistent childhood onset ADHD. J Consult Clin Psychol 70(1):153–157. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.153

Pingault J-B, Tremblay RE, Vitaro F, Carbonneau R, Genolini C, Falissard B, Côté SM (2011) Childhood trajectories of inattention and hyperactivity and prediction of educational attainment in early adulthood: a 16-year longitudinal population-based study. Am J Psychiatry 168(11):1164–1170. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10121732

Puig-Antich J, Ryan N (1986) The schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (Kiddie-SADS)-1986. Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, Pittsburgh

Rasmussen P, Gillberg C (2000) Natural outcome of ADHD with developmental coordination disorder at age 22 years: a controlled, longitudinal, community-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39(11):1424–1431. doi:10.1097/00004583-200011000-00017

Rettew DC, Copeland W, Stanger C, Hudziak JJ (2004) Associations between temperament and DSM-IV externalizing disorders in children and adolescents. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25(6):383–391. doi:10.1097/00004703-200412000-00001

Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF (2000) The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: a quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull 126(1):3–25. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3

Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, Aluwahlia S (1983) A Childrens Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch Gen Psychiatry 40(11):1228–1231. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010

Shiner RL, Buss KA, McClowry SG, Putnam SP, Saudino KJ, Zentner M et al (2012) What is temperament now? Assessing progress in temperament research on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Goldsmith et al. Child Dev Perspect 6(4):436–444. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00254.x

Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E (2007) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. J Pediatr Psychol 32(6):631–642. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm005

Taylor E, Sandberg S, Thorley G, Giles S (1991) The epidemiology of childhood hyperactivity, vol 33. Institute of Psychiatry/Oxford University Press, Oxford

Turgay A, Goodman DW, Asherson P, Lasser RA, Babcock TF, Pucci ML, Barkley R (2012) Lifespan persistence of ADHD: the life transition model and its application. J Clin Psychiatry 73(2):192–201. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06628

Uchida M, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV, Biederman J (2015) Adult outcome of ADHD an overview of results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of pediatrically and psychiatrically referred youth with and without ADHD of both sexes. J Atten Disord. doi:10.1177/1087054715604360

Weiss G, Hechtman L, Milroy T, Perlman T (1985) Psychiatric status of hyperactives as adults: a controlled prospective 15-year follow-up of 63 hyperactive children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 24(2):211–220. doi:10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60450-7

Wender EH (1995) Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorders in adolescence. J Dev Behav Pediatr 16(3):192–195. doi:10.1097/00004703-199506000-00008

Wilens T, Upadhyaya H (2007) Impact of substance use disorder on ADHD and its treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 68(8):e20

Wilens T, Biederman J, Spencer TJ (2002) Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Annu Rev Med 53:113–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103945

Wilson JM, Marcotte AC (1996) Psychosocial adjustment and educational outcome in adolescents with a childhood diagnosis of Attention Deficit Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35(5):579–587. doi:10.1097/00004583-199605000-00012

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health: DA000357; DA023668; DA032573; MH064769; MH53063, and MH57451.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tandon, M., Tillman, R., Agrawal, A. et al. Trajectories of ADHD severity over 10 years from childhood into adulthood. ADHD Atten Def Hyp Disord 8, 121–130 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-016-0191-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-016-0191-8