Abstract

A number of evidence-based treatments are available for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), including pharmacological, psychosocial, or a combination of the two treatments. For a significant number of children diagnosed with ADHD, however, these treatments are not utilized or adhered to for the recommended time period. Given that adherence to treatment regimens is necessary for reducing the symptoms of ADHD, it is crucial to develop a comprehensive understanding of why adherence rates are so low. The current review examines the literature to date that has directly explored utilization and adherence issues related to the treatment of ADHD in order to identify the key barriers to treatment. This review focused on four main factors that could account for the poor rates of treatment utilization and adherence: personal characteristics (socio-demographic characteristics and diagnostic issues), structural barriers, barriers related to the perception of ADHD, and barriers related to perceptions of treatment for ADHD. This review included 63 papers and covered a variety of barriers to treatment that have been found in research to have an impact on treatment adherence. Based on this review, we conclude that there are complex and interactive relationships among a variety of factors that influence treatment utilization and adherence. Four main gaps in the literature were identified: (1) there is limited information about barriers to psychosocial interventions, compared to pharmacological interventions; (2) there is a limited variety of research methodology being utilized; (3) treatment barrier knowledge is mostly from parents’ perspectives; and (4) treatment utilization and treatment adherence are often studied jointly. Information from this review can help practitioners to identify potential barriers to their clients being adherent to treatment recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a chronic and complex mental health disorder characterized by developmentally inappropriate levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association [APA] 2013). Recent large-scale epidemiological studies in the USA have estimated the prevalence of ADHD at 5 % in school-aged children (APA 2013), and as such, ADHD is one of the most common diagnoses provided to children at outpatient mental health services (Staller 2006). ADHD is also associated with serious behavioural, academic, and social difficulties, which often persist into adolescence and adulthood (Schachar 2009).

A significant body of research exists to support the idea that the symptoms of ADHD and associated impairments in social, occupational, or academic functioning can be successfully reduced using: (1) medication (e.g. methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, or atomoxetine), (2) behaviour modification (e.g. parent training, classroom contingency management), and (3) a combination of the two (Kaiser and Pfiffner 2011; Vaughan et al. 2012). Psychostimulant medications are the pharmacological treatment most often prescribed for ADHD (Swanson 2003) and have been shown to significantly reduce the core symptoms of ADHD (e.g. MTA Cooperative Group 2004). Less research has examined the impact of psychosocial interventions, which include a variety of strategies such as reward systems, social skills training, and behavioural interventions; however, these treatments have also been shown to have beneficial effects for children with ADHD (Kaiser and Pfiffner 2011).

Debate continues in the literature as to the relative benefits of medication, psychosocial intervention, and a combination of these two treatments. Results from the 14-month time point in the largest trial ever conducted on treatments of ADHD in elementary-aged children (MTA Cooperative Group 1999) found that combined treatment (i.e. medication and psychosocial intervention together) and medication management did not differ significantly in terms of their impact on the majority of ADHD symptoms. Moreover, combined treatment and medication management proved more effective than a psychosocial intervention or regular community care. Combined treatment was superior to medication management for some associated symptoms, but not core ADHD symptoms. More recently, researchers have described combined treatment (i.e. medication and behavioural management) as necessary (Chronis et al. 2006) and as the gold standard (Daly et al. 2007) in the treatment of children with ADHD. The International Consensus Statement on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and disruptive behaviour disorders (DBDs; Kutcher et al. 2004) and the Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with ADHD (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2007) have also recognized the importance of both forms of treatment for ADHD.

What we can definitely conclude from research is that highly effective treatments for ADHD have been developed. Unfortunately, research conducted around the world has also determined that ADHD is undertreated (Cuffe et al. 2009; Ford et al. 2008; Vanheusden et al. 2008). A large epidemiological study of children in the USA who were diagnosed with ADHD found that over a 1-year period, only about 12 % were treated with medication and only 30 % had received some sort of psychosocial intervention (Jensen et al. 1999). Similar rates have been found in Australia, with 28 % of children with ADHD receiving some sort of service in the past 6 months and 18.3 % taking a type of medication (Sawyer et al. 2004). Jensen et al. (1999) concluded that in the USA, only 46 % of children with ADHD who needed medication, 32 % of children with ADHD who needed counselling, and 26.5 % of families who needed help with their child’s behaviour problems had received the intervention they needed.

Lack of treatment is in part related to the fact that families and children do not always act on treatment recommendations. Overall, treatment initiation rates of approximately 65 % are commonly reported (e.g. Brown et al. 1987; MacNaughton and Rodrigue 2001) with families being somewhat more likely to pursue recommendations for medication than for psychological or counselling interventions (Bennett et al. 1996; MacNaughton and Rodrigue 2001). It is important to note, however, that beginning treatment does not necessarily mean that families and children continue with treatment. Studies have found that approximately 25 % of children and families discontinued treatment with stimulant medication over a 1-year period (Corkum et al. 1999; Faraone et al. 2007). Over a 5-year period, Charach et al. (2004) found that adherence rates declined even further, to 53 % of children adhering after 2 years and to 36 % adhering after 5 years. Even in the short term (i.e. over a 4-week period), research has shown that only about 40 % of children take every dose of medication prescribed (Gau et al. 2006).

In a review of psychosocial treatments for ADHD, Pelham et al. (1998) reported that only a small number of behaviour intervention studies actually measured adherence to treatment, making definitive adherence estimates (and the determination of treatment fidelity) difficult. Two studies that did measure adherence to parent training programs reported very similar rates. In a Canadian study, Corkum et al. (1999) found that over the 12 months of their study, 57.7 % of families attended more than half of the parent sessions. A parent training study in Taiwan (Huang et al. 2003) found that 14 of the 23 families (61 %) completed a 10-week program. Low levels of treatment adherence are not unique to the field of ADHD, but are an issue in paediatric medicine in general. For example, adherence to medication treatments for cystic fibrosis has been found to be approximately 64 % (Zindani et al. 2006), while adherence to dietary recommendations associated with medical treatments is often under 50 % (Mackner et al. 2001).

The wide-spread under-treatment of ADHD seems then to be due to a combination of children and families not beginning treatment at all and the lack of adherence to recommended treatments. Given that ADHD symptoms are associated with significant, long-term behavioural, academic, and interpersonal challenges and that effective treatments are available but under-utilized, it is crucial that we develop a comprehensive understanding of the barriers preventing children and families from beginning and/or adhering to treatment.

Owens et al. (2002) examined barriers to the delivery of children’s mental health services in general. They identified three broad categories including: (1) structural barriers (e.g. long waiting lists or cost); (2) barriers related to perceptions about mental health problems (e.g. denial of the severity of the problem); and (3) barriers related to perceptions about mental health treatment services (e.g. lack of confidence in professionals or stigma related to receiving treatment). They also found that psychosocial characteristics of the family and children were related to the number of reported barriers. Despite the fact that ADHD is one of the most commonly researched disorders in children and adolescents, surprisingly little research has examined the barriers to treatment for children and families coping with this disorder. As a result, little is known about the specific barriers that are preventing families of children with ADHD from initiating or continuing with recommended treatments for this disorder. The goal of this review was to systematically examine and summarize this body of literature. This review is structured around the three broad categories reported above (i.e. based on the categories put forth by Owens et al. 2002) and will also examine socio-demographic factors and factors related specifically to the diagnosis of ADHD. We also created themes within each category based on a qualitative review and grouped information into these themes as subcategories.

Methods

A review of the literature was conducted using three databases: (1) PsycINFO (www.apa.org/psycinfo), (2) PubMED (www.pubmed.gov), and (3) ERIC (www.eric.ed.gov). For the database search, the term ADHD was paired with each of the following terms: treatment, adherence, compliance, barrier, utiliz*, media, and behaviour. Table 1 provides an overview of the studies identified that met the following criteria: (1) a stated goal of the research study to evaluate factors related to ADHD treatment utilization and adherence, (2) a publication date of 1987 (corresponding to the publication of the DSM-III-R; APA 1987) or later, and (3) publication in a peer-reviewed journal. Case studies, literature reviews, book chapters, student theses, and studies in languages other than English were excluded from the review. It is important to note that articles that only reported adherence rates as part of a larger study were not included. However, several articles that did not meet the review inclusion criteria are cited throughout the text to provide an overall context for the findings.

Results and discussion

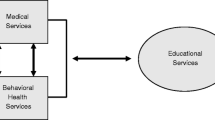

After the review of the literature, 63 studies were found that met our inclusion/exclusion criteria; these can be found in Table 1. As mentioned above, several articles that did not meet criteria are included in order to provide relevant context. These articles are clearly indicated in footnotes. The findings in this review have been divided into four main sections. The first section, personal characteristics, includes a discussion of the relationships among socio-demographic factors and ADHD treatment utilization and adherence, as well as a review of the diagnostic issues that are potentially related to treatment barriers. The next three sections are organized according to the categories of barriers to child mental health treatment identified by Owens et al. (2002): structural barriers, barriers related to perceptions of ADHD, and barriers related to perceptions of treatment for ADHD. See Fig. 1 for a graphical representation.

-

1.

Personal characteristics (i.e. socio-demographic and diagnostic)

Most of the research that has studied factors related to treatment utilization and adherence in children with ADHD has focused on socio-demographic and diagnostic factors. Of the 63 articles reviewed, 30 of the studies cited socio-demographic and diagnostic barriers to treatment. Studies examining pharmacological, psychosocial, and combination treatments were reviewed. The following variables have all been shown to be related to diagnostic and treatment patterns for ADHD: (i) sex, (ii) age of the child, (iii) ethnicity, (iv) socio-economic status (SES), and (v) comorbid diagnoses. Each of these will be discussed below. Other barriers identified in this category were being from a single-parent home (Bird et al. 2008) and negative family influences (e.g. parental stress, parental psychopathology, etc.; Schneider et al. 2013). These types of barriers were not as often identified as the five identified above.

(i) Sex It is estimated that the ratio of diagnosis of ADHD is approximately four males to every female (APA 2000), although some researchers believe that ADHD in females may be underdiagnosed. Among those children diagnosed with ADHD, boys have been found to be more likely to receive treatment (Barbaresi et al. 2006; Bussing et al. 1998). In terms of help-seeking, one study found that parents of boys with ADHD reported taking more help-seeking steps (e.g. speaking to someone about ADHD) than parents of girls with ADHD (Bussing et al. 2005). Moreover, another study found that boys in their sample of children at high risk for ADHD were five times more likely to receive an evaluation, diagnosis, or treatment than girls (Bussing et al. 2003b).

Graetz et al. (2006) compared service use patterns and associated factors for 398 children (279 males) with ADHD. Similar to previous research, the main finding was that proportionately more boys than girls received medication. Although boys and girls did not differ in terms of their rates of counselling service use or the types of services they used, the factors associated with service use were different between sexes. For boys, academic problems and the number of behavioural symptoms were the main predictors of service use, whereas for girls, the presence of a comorbid depressive disorder was the main predictor (Graetz et al. 2006). One study reported that females were both more adherent to and persistent with treatment than males (Barner et al. 2011). Adherence was defined as the number of days the patient was in possession of their medication, while persistence was defined as the number of days of continuous therapy (Barner et al. 2011).

(ii) Age of child In general, younger children are more likely than adolescents to comply with prescribed pharmacological treatment (Atzori et al. 2009; Barner et al. 2011; Berger-Jenkins et al. 2012; Gau et al. 2008; Miller et al. 2004; Thiruchelvam et al. 2001). In contrast, Ohan and Johnston (2000) had 44 parents and adolescents make a general estimate of the adolescents’ adherence to medication. In addition, participants were asked to estimate the number of doses taken over the past week and over the past 24 h. This information was collected during an initial interview and again after 2 months. Nearly half of the parents and adolescents reported over 90 % adherence at both time points. The authors did not expect adherence rates to be this high and offered several potential explanations. For example, the sample was drawn from adolescents who were currently being prescribed medication and excluded those who were not seeking medication even if they might have benefited from it (which could be interpreted as non-adherence). Furthermore, participants could have overestimated or been deceptive with their reports. Also, the sample could be biased towards low-conflict homes in which the parent and adolescent were willing to participate in research together, possibly eliminating participants from high-conflict homes. Another offered explanation was that anecdotal reports of low adherence rates in adolescents may be biased by the saliency of the “difficult-to-treat” minority of adolescents.

(iii) Ethnicity There is little research specifically investigating ethnicity in relation to adherence and uptake of psychosocial interventions for ADHD. Some reports indicate that children from minority ethnic groups were generally less likely to accept and receive services for ADHD than were Caucasian children (Bussing et al. 2003b; dosReis et al. 2003; Hong et al. 2013; Krain et al. 2005; Palli et al. 2012; Ray et al. 2006; Schneider et al. 2013; Stevens et al. 2005). However, some studies found that ethnic minority parents were equally likely to find treatments acceptable (Arnold et al. 2003; Tarnowski et al. 1992). Krain et al. (2005) results indicated that 79 % of Caucasian parents in their study pursued medication as a treatment for their child’s ADHD, while only 27 % of non-Caucasian parents did so. In Bussing et al. (2007) study, which explored cultural variance in parental health beliefs and knowledge and information sources related to ADHD, African American parents reported less awareness of ADHD and rated their own knowledge of ADHD lower than their Caucasian counterparts. They also reported receiving fewer cues to action, such as being given ADHD information from teachers or reading media accounts, than their Caucasian counterparts.

A number of researchers have proposed that one possible explanation for why children from minority ethnic groups are less likely to receive treatment is that their cultures foster different beliefs and attitudes about mental health disorders and appropriate treatments. For example, Arcia et al. (2004) found that Latina mothers were concerned that stimulant medications had serious side effects or that their children would become addicted to stimulant medications.

(iv) Socio-economic status (SES) Research indicates that families with lower SES are less likely to pursue and/or adhere to treatment for ADHD (Arnold et al. 2003; Brown et al. 1987; Bussing et al. 2003b). Rieppi et al. (2002) studied several SES variables within a large sample from a randomized clinical trial of treatments for ADHD (i.e. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD). Overall, they found that rates of adherence were significantly related to parents’ income, education, and job status, with higher levels of these three variables associated with greater treatment adherence. When types of treatments were analysed separately, they found that medication adherence was not related to any of the SES variables. In contrast, adherence to psychosocial and combination treatment regimes was significantly related to all of the SES variables. In addition, families who regularly attended psychosocial treatment sessions were significantly more likely to include two-parents. Others, however, have contradicted these findings (Brownell et al. 2006). Their results showed that the probability of methylphenidate use (i.e. adherence rate or prescription rate) at the end of a 2-year longitudinal study was inversely related to SES. Specifically, as SES decreased, methylphenidate use increased. Thus, the impact of SES on treatment utilization and adherence appears to vary by treatment type, with stimulant medication rates being either unaffected or increasing with lower SES, and psychosocial treatment and adherence increasing with higher SES.

(v) Comorbid diagnoses Little research has investigated the impact of comorbid diagnoses on issues related to ADHD treatment utilization and adherence. As mentioned previously, one study found that girls with ADHD and comorbid depression were more likely to receive and adhere to intervention than were girls with ADHD who were not depressed (Graetz et al. 2006). Sitholey et al. (2011) found that children with comorbid mental retardation (now “intellectual disability” in the DSM-5) were less likely to adhere to treatment. In a longitudinal study (Thiruchelvam et al. 2001) that followed 71 children with ADHD who were prescribed methylphenidate over 3 years, medication adherence decreased over time and having a comorbid diagnosis was significantly associated with treatment non-adherence. Specifically, children with high levels of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) symptoms at school were 11 times more likely to discontinue medication than children without ODD symptoms. Anxiety was also identified as a moderator of adherence. Conduct disorder (CD) and learning disorder (LD) were also analysed but were not found to have a moderating effect. The results of these studies suggest that comorbid disorders may be important factors in the utilization of and adherence to treatment, and that further research is needed to delineate which disorders are of greatest consequence and in which populations.

-

2.

Structural barriers

Structural barriers are the characteristics of the treatment, the health system, or the family that make it challenging for families to initiate or comply with treatment. This term encompasses the logistical elements of treatment, including cost, time requirements, transportation, availability of service providers, etc. Of the 63 studies reviewed, 22 studies examined structural barriers to treatment, including: (i) financial burdens and (ii) system barriers (i.e. counselling feasibility and medication inconveniences).

(i) Financial burden of treatment One of the primary structural barriers identified in this review was the financial cost of the treatment for ADHD (Chan et al. 2002; Guevera et al. 2001; Kelleher et al. 2001; Sawyer et al. 2004; Sitholey et al. 2011). Bussing et al. (2003b) found that of the 91 families in their study who had not received treatment, 38 % reported that the main reason they did not pursue treatment was the cost. Annual medical costs for children with ADHD tend to be more than double the cost for children without ADHD (Leibson et al. 2001). In a study that compared treatment costs for asthma compared to ADHD, families of children with ADHD paid more prescription-related costs and out-of-pocket expenses (Chan et al. 2002). Moreover, Swensen et al. (2003) found that parents and siblings of a child with ADHD were also more likely to have increased medical costs, often due to the stress incurred from having a child/sibling with ADHD (twice as much for families with a child with ADHD vs. matched comparison families). Cost may also interact with SES to impact treatment utilization and adherence, as cost would likely be a larger barrier for families of lower SES than for families of higher SES. It is also important to note that the cost of treatment and the availability of service providers are factors that vary across countries and cultures.

Having a child with ADHD can also have a significant impact on parents’ employment. While a study by Perrin et al. (2005)Footnote 1 did not meet the criteria of our review, it does provide important information. The authors interviewed employers of 41 companies across the USA to find out how supportive their policies were for employees who have children with ADHD. The interviews included questions regarding: (1) knowledge of ADHD diagnosis and prevalence, (2) knowledge of associated costs, (3) general philosophy regarding benefits, and (4) knowledge of how ADHD impacts employees. They found most employers did not realize the significant burden placed on families who have a child with ADHD and that most company insurance policies were not supportive in terms of the needs for families with a child with ADHD. For example, most companies did not cover the cost of behavioural therapy.

(ii) System barriers System barriers are features of the healthcare and social system, broadly defined, that affect the likelihood that a person will accept and adhere to treatment. System barriers are experienced by between 35 and 53 % of families attempting to obtain treatment for their child with ADHD (Bussing et al. 2003b; Owens et al. 2002). Barriers such as lack of time, lack of teacher cooperation, advice from child’s school, lack of insurance coverage, frustration with guidance provided, and problems in hospitals (e.g. long waiting time) have been identified (Brinkman et al. 2009; Cormier 2012; Davis et al. 2012; Dreyer et al. 2010; Sitholey et al. 2011; Stevens et al. 2005; Zima et al. 2012). Bennett et al. (1996) hypothesized that counselling feasibility (e.g. scheduling flexibility, travel distance) would predict adherence to treatment, as found in earlier research. Only 54 % of their sample initiated the recommended counselling; however, they did not find a relationship between parent-rated counselling feasibility and adherence. Therefore, it seems as though there are other factors above and beyond feasibility that predict adherence.

The inconvenience of taking medication several times per day has been noted as a barrier for adherence to stimulant medications for ADHD (Barner et al. 2011; Gau et al. 2006, 2008; Sitholey et al. 2011). Certain types of stimulant medications are now available in extended-release (long-acting) form, which requires only one dose per day (Rothenberger et al. 2011). Reducing the number of doses per day creates a simpler medication regimen and has been found to increase compliance with taking stimulant medication for ADHD (Marcus et al. 2005). Physicians are moving away from prescribing short-acting medications, with one study finding that prescriptions for short-acting medications have been on the decline since 1999 (Scheffler et al. 2007) (see footnote 1). Despite their convenience, long-acting medications are more costly than short-acting medications (Scheffler et al. 2007). While the Scheffler et al. (2007) study did not directly assess barriers to treatment for ADHD and therefore was not included in our review, it can be theorized that cost of medication may interact with SES. The issue of medication cost may make short-acting medication more available to families of lower SES, which could increase the burden of structural barriers and contribute to non-adherence to medication as a treatment.

Some children are physically unable to swallow pills or experience severe anxiety when attempting to do so (Beck et al. 2005). A significant problem for children with pill-swallowing difficulties is that some of the newer extended-release forms of stimulant medication cannot be crushed prior to ingestion (Beck et al. 2005). One solution to this problem has been to implement a behavioural training program for pill-swallowing. Beck et al. (2005) applied this approach for children with ADHD and achieved high levels of success. Another alternative has been developed recently in the form of a transdermal system (i.e. a patch), which adheres to the skin and releases methylphenidate (Pelham et al. 2005) (see footnote 1). This study did not meet the criteria for our review, but offers an alternative to pills, which may improve adherence. The patches were generally well tolerated by study participants, with a small minority of children reporting mild discomfort during removal. This system could help solve the problem of remembering to take a pill several times per day and could be helpful for children who find swallowing pills difficult. However, this patch is not available in all countries.

-

3.

Barriers Related to Parents’ Perception of ADHD

This cluster of barriers refers to the way in which parental knowledge and beliefs regarding ADHD can affect decisions to pursue and adhere to treatment. Studies that discussed these barriers referred to: (i) the amount of knowledge a parent has about ADHD, (ii) how much parents perceive the disorder to impact their child/family life, and (iii) their opinions regarding the cause of ADHD. Of the 63 studies, 20 studies addressed these barriers.

(i) Knowledge of ADHD research has demonstrated that treatment patterns for children with ADHD can vary based on how much their parents know about the disorder. For example, Bennett et al. (1996) and Liu et al. (1991) found that the more parents knew about ADHD, the more accepting they were of medication as a treatment. In addition, Corkum et al. (1999) found that families were more likely to enrol in treatment if they had higher knowledge of ADHD; however, knowledge of ADHD was not related to adherence. Bailey and Owens (2005) found that lack of knowledge about ADHD was a significant barrier to treatment for African American children. Sitholey et al. (2011) identified parents’ notion that ADHD symptoms will subside on their own as a barrier to treatment in 30 % of their sample.

One large-scale study included 658 families of children with ADHD, for which parents had either declined or discontinued medication for their child (Monastra 2005). In this study, 90 % of the sample had previously reported feeling uncomfortable putting their children on medication without a direct test of attention. To address this, the researchers administered both computerized and electroencephalographic quantitative evaluations of attention to all children in the study. The results of these tests were presented to parents in combination with a neuro-educational intervention program about ADHD. In addition, a comprehensive care plan treatment manual was sent home. Following these procedures, over 70 % of parents started their children on a pharmacological treatment. At the 2-year follow-up, 95 % of the initial group of children were still taking medication for ADHD. Therefore, it appears that adequate information about ADHD and treatments can substantially increase uptake and adherence.

(ii) Perceived severity and cause of symptoms The way a parent perceives the behaviour of his or her child can influence the decision to pursue, accept, and adhere to treatment (Angold et al. 1998; Brownell et al. 2006; Charach et al. 2004; Maniadaki et al. 2006; Owens et al. 2002; Sayal et al. 2006; Sawyer et al. 2004; Tarnowski et al. 1992). It has also been found that parents who perceive their career is being negatively affected by their child’s behaviour are more likely to seek treatment (Sayal et al. 2003). Stigma and scepticism of diagnosis have also been identified as barriers to beginning treatment (Ahmed et al. 2013a; Bailey and Owens 2005; Brinkman et al. 2009). Believing that their child would outgrow the disorder (Cormier 2012) or that the disorder was caused by poor parenting also delayed treatment (Davis et al. 2012). These beliefs about cause of disorder may differ across culture; for example, Bussing et al. (2007) found that African American parents attributed more causation to sugar intake.

-

4.

Barriers related to perceptions about treatment of ADHD

The final barrier category identified in this review is related to perceptions about treatment for ADHD (addressed by 28 of the 63 studies included in the review). Treatments for ADHD, especially stimulant medications, have been widely publicized in the media. Therefore, many parents have preconceived notions about various treatments—often based on misconceptions—which can prevent them from obtaining and/or adhering to treatment for their child. Categories included in this section are (i) treatment acceptability and (ii) stigma-related barriers.

(i) Treatment acceptability Treatment acceptability refers to the beliefs and attitudes regarding which treatments are appropriate, fair, and reasonable, given the nature and severity of the problem (Kazdin 1981). The present literature review revealed the robust finding that parents rate psychosocial treatments as more acceptable than pharmacological ones for children with ADHD (dosReis et al. 2006; Dreyer et al. 2010; Gage and Wilson 2000; Liu et al. 1991; Miltenberger et al. 1989; Monastra 2005; Power et al. 1995; Tarnowski et al. 1992; Wilson and Jennings 1996). This is likely due to parents’ fears about personality changes, “zombie”-like side effects, and worries about future substance addiction (e.g. Ahmed et al. 2013a; Davis et al. 2012). In addition, interventions that emphasize positive reinforcement rather than punishment, and those that require relatively little time and effort, are perceived as more acceptable to parents (Reimers et al. 1992). Studies have shown that parent acceptability of and attitudes towards treatment are related to treatment seeking and adherence (Bird et al. 2008; Corkum et al. 1999). Medication concerns have also been associated with less follow-up and less utilization of treatment (Berger-Jenkins et al. 2012). Several other factors, including a child’s history of medication use and counselling for ADHD (Rostain et al. 1993) (see footnote 1) have also been shown to be positively related to parent acceptability of ADHD interventions.

In a study by Krain et al. (2005), parent acceptability accurately predicted initiation of medication 3–4 months later in 83.7 % of cases. However, acceptability of behaviour therapy did not predict psychosocial treatment initiation. One reason the authors give for this finding is that ratings of behaviour therapy were consistently high, which did not provide enough variability to distinguish high and low acceptability. Some of the potential reasons put forth by the authors as factors that may have influenced the families’ decision not to pursue behaviour therapy included unavailability of a qualified behaviour therapist, lack of time, and financial concerns. In contrast to these findings, Bennett et al. (1996) found no relation between parent ratings of counselling acceptability, medication acceptability, and adherence to recommendations for either type of treatment 4 months after acceptability information was collected.

As mentioned earlier, ethnic differences in treatment acceptability for ADHD have been reported in several studies. Bussing et al. (2007) found that African American parents expected less benefit from treatment. Similarly, another study reported that African American families had higher rates of negative treatment expectations (e.g. did not expect treatment would be successful, distrusted professionals; Bussing et al. 2003a). Arcia et al. (2004) found that Latina mothers had strong reservations about allowing their children to take stimulant medication. Families from minority backgrounds were also found to view medication as an unattractive treatment option, to be less satisfied with medication, and to be more likely to believe that medication for ADHD is associated with negative side effects (dosReis et al. 2003).

(ii) Stigma-related barriers Stigma-related barriers are those having to do with others’ negative attitudes towards ADHD and ADHD treatment. Historically, there has been substantial stigma associated with mental health diagnosis and treatment. As noted by Johnston and Fine (1993) (see footnote 1), poor treatment adherence in the paediatric and ADHD research literature may be in part related to negative publicity surrounding particular interventions (e.g. stimulant medication), as well as concerns regarding side effects. This was demonstrated in our review, with several studies finding fear of side effects to be a barrier (Ahmed et al. 2013a; Brinkman et al. 2009; Coletti et al. 2012; Cormier 2012; Sitholey et al. 2011). Although knowledge about the effectiveness of treatment has continued to grow and has been more widely disseminated, this stigma still exists and is particularly salient in the case of ADHD. Several studies in our review found stigma to be a barrier to treatment (e.g. Cormier 2012; Zima et al. 2012). Bussing et al. (2003b) found that 39 % of the parents they surveyed reported a stigma-related barrier to getting help for their child with ADHD. For example, parents reported concerns about being negatively perceived by others. In addition, parents reported stigma barriers more when they had a daughter with ADHD.

Researchers have, in part, blamed the media for its inaccurate portrayals of the disorder. While no studies included in our review assessed this directly, there has been some interesting research into the way that ADHD is portrayed in the media. Schmitz et al. (2003) (see footnote 1) examined social representations of ADHD that were located from print media sources (e.g. MacLean’s, People Magazine) in the USA between 1988 and 1997. They concluded that ADHD was portrayed as a disorder that affected Caucasian males. Furthermore, the disorder was commonly reported as being over-diagnosed, and stimulant medication was portrayed as an over-prescribed treatment. These findings are consistent with Danforth and Navarro (2001) (see footnote 1), who had research assistants document any references to ADHD encountered in their daily lives in spoken, written, or other formats. They also concluded that the media was in part responsible for the stigma associated with ADHD by discussing ADHD in connection with tragic events like murders.

Conclusions

The present review was conducted to gain a better understanding of the factors that explain why a large percentage of children diagnosed with ADHD are not receiving evidence-based treatment. Our review, which is consistent with past reviews (e.g. Ahmed et al. 2013b; Calvert and Johnston 1990; Cromer and Tarnowski 1989; Reimers et al. 1987; Swanson 2003), indicates that there are many complex and interactive relationships among a variety of factors, all of which influence families’ decision-making in regard to selecting and adhering to treatment(s) for children with ADHD. Our review identified four major gaps existing in the literature, which will need to be addressed in order to better understand the weight of each of the identified factors that impact utilization and adherence for treatment of ADHD in children.

One of the most apparent gaps is that the majority of the factors highlighted in this review are related to pharmacological treatment adherence. Although both pharmacological and psychosocial treatments are included in most of these studies, the weight of the research is concentrated on factors related to the utilization of and adherence to medication. Less is known about what influences parents’ decision to enrol in and/or adhere to counselling, behaviour therapy, or other forms of psychosocial interventions.

The second gap in the literature is that the two types of non-compliance with treatment are often studied jointly. These are (1) treatment utilization (i.e. whether the family begins treatment), and (2) treatment adherence (i.e. whether the family continues treatment after starting). Although it seems likely that different factors contribute to each of these types of non-adherence, most of the research completed thus far has either failed to differentiate between the two or has focused only on non-adherence. Many of the samples in the studies reviewed here are comprised of parents who have already enrolled in treatment. This eliminates the possibility of learning about parents who declined treatment altogether.

The third gap is that most of the information in the current review comes from research that was completed with parents. Research is greatly needed that includes the perspectives of other people involved in the care of children with ADHD, such as clinicians, family physicians, and teachers of children, as well as youth diagnosed with ADHD. Gaining the opinions and knowledge from a more varied sample of individuals who work with and care for youth with ADHD, as well as from the youth themselves, is essential to developing a broad understanding of why many children with ADHD are not receiving sufficient treatment.

The fourth and final gap in the literature is the use of limited types of methodology. Most of the studies were based on the results of questionnaires given to parents of children with ADHD. This is an efficient way of obtaining a large amount of data quickly; however, more varied methods (including both qualitative and experimental research designs) must be employed in order to gain comprehensive information that can be applied in clinical settings. Moreover, many of the studies focused on specific, isolated variables such as ethnicity or gender. Studies are needed that examine a range of variables, including those identified in this review, and that employ a variety of methodologies within a single, representative sample.

It is also interesting to consider how these barriers to treatment for ADHD differ from barriers to treatment for other chronic health conditions, such as depression, diabetes, and arthritis. A study by Shen et al. (2013) found that barriers to treatment for diabetes include a lack of trustworthy information sources, deficits in communications between clients and healthcare professionals, and restrictions of reimbursement regulations (i.e. financial burden). A study examining barriers to pain management in patients with arthritis found that the primary barriers were surrounding worries about medication side effects, concerns about drug interactions, and fear of addiction (Fitzcharles et al. 2009). Barriers to depression treatment have been identified as lack of readiness to seek help, negative perceptions about medication, and transportation concerns, among others (Wells et al. 2013). These barriers are similar to those identified in this review, indicating that similar barriers are at play across different chronic health conditions.

In summary, more research is needed to further understand the complexity of ADHD treatment barriers and how these factors interact. Given the high prevalence rates of ADHD, the known negative impacts across multiple domains of functioning, and the strong empirical evidence for the effectiveness of a number of treatments, it is crucial to further examine why children are not receiving evidence-based treatments. In order to fully understand and ultimately overcome these barriers, studies are urgently required that include multiple variables and use divergent methods within a single representative sample. Another important area of future research would be to develop a model of adherence, which would facilitate focused research in this area and ultimately allow for a quantitative review of adherence to be conducted. Information about treatment barriers will help to inform the type of education required to ensure that parents and their children with ADHD initiate and adhere to evidence-based treatments.

Notes

This study was not included in our review, but provides important context for the overall paper.

References

*Asterisks indicate which articles are included in the table

*Ahmed R, Borst J, Wei YC, Aslani P (2013a) Parents’ perspectives about factors influencing adherence to pharmacotherapy for ADHD. J Atten Disord. doi:10.1177/1087054713499231

Ahmed R, McCaffery KJ, Aslani P (2013) Factors influencing parental decision making about stimulant treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 23:163–178

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2007) Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46:894–921

American Psychiatric Association (1987) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd edn. (revised). APA, Washington

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. (text revised). APA, Washington

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. APA, Washington

*Angold A, Messer SC, Stangl D, Farmer EM, Costello EJ, Burns BJ (1998) Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Am J Public Health 88:75–80

*Arcia E, Fernandez MC, Jaquez M (2004) Latina mothers’ stances on stimulant medication: complexity, conflict, and compromise. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25:311–317

*Arnold LE, Elliot M, Sachs L, Bird H, Kraemer HC, Wells KC, Abikoff HB, Comarda A, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Greenhill LH, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Hoza B, Jensen PS, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Wigal T (2003) Effects on ethnicity on treatment attendance, stimulant response/dose, & 14-month outcome in ADHD. J Consult Clin Psychol 71:713–727

*Atzori P, Usala T, Carucci S, Danjou F, Zuddas A (2009) Predictive factors for persistent use and compliance of immediate-release methylphenidate: a 36-month naturalistic study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 19:673–681

*Bailey RK, Owens DL (2005) Overcoming challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc 97:5S–10S

*Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Leibson CL, Jacobsen SJ (2006) Long-term stimulant medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a population-based study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 27:1–10

*Barner JC, Khoza S, Oladapo A (2011) ADHD medication use, adherence, persistence and cost among Texas Medicaid children. Curr Med Res Opin 27:13–22

*Beck MH, Cataldo M, Slifer KJ, Pulbrook V, Guhman JK (2005) Teaching children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autistic disorder (AD) how to swallow pills. Clin Pediatr 44:515–526

*Bennett DS, Power TJ, Rostain AL, Carr DE (1996) Parent acceptability and feasibility of ADHD interventions: assessment, correlates, and predictive validity. J Pediatr Psychol 21:643–657

*Berger-Jenkins E, McKay M, Newcorn J, Bannon W, Laraque D (2012) Parent medication concerns predict underutilization of mental health services for minority children with ADHD. Clin Pediatr 51:65–76

*Bird HR, Shrout PE, Duarte CS, Shen S, Bauermeister JJ, Canino G (2008) Longitudinal mental health service and medication use for ADHD among Puerto Rican youth in two contexts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 47:879–889

*Brinkman WB, Sherman SN, Zmitrovich AR, Visscher MO, Crosby LE, Phelan KJ, Donovan EF (2009) Parental angst making and revisiting decisions about treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 124:580–589

*Brown RT, Borden KA, Wynne ME, Spunt AL, Clingerman SR (1987) Compliance with pharmacological and cognitive treatments for attention deficit disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 26:521–526

*Brownell MD, Mayer T, Chateau D (2006) The incidence of methylphenidate use by Canadian children: what is the impact of socioeconomic status and urban or rural residence. Can J Psychiatry 51:847–854

*Bussing R, Gary FA, Mills TL, Garvan CW (2003a) Parental explanatory models of ADHD: gender and cultural variations. Soc Psychiatr Epidemiol 38:563–575

*Bussing R, Gary FA, Mills TL, Garvan CW (2007) Cultural variations in parental health beliefs, knowledge, and information sources related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Fam Issues 28:291–318

*Bussing R, Koro-Ljungberg ME, Gary F, Mason D, Garavan C (2005) Exploring help-seeking for ADHD symptoms: a mixed-methods approach. Harv Rev Psychiatry 13:85–101

*Bussing R, Zima BT, Belin TR (1998) Differential access to care for children with ADHD in special education programs. Psychiatr Serv 49:1226–1229

*Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Garvan CW (2003b) Barriers to detection, help-seeking, and service use for children with ADHD symptoms. J Behav Health Serv Res 30:176–189

Calvert SC, Johnston C (1990) Acceptability of treatments for child behaviour problems: issues and implications for future research. J Clin Child Psychol 19:61–75

*Chan E, Zhan C, Homer CJ (2002) Health care use and costs for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: national estimates from the medical expenditure panel survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 156:504–511

*Charach A, Ickowicz A, Schachar R (2004) Stimulant treatment over five years: adherence, effectiveness, and adverse effects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:559–567

Chronis AM, Jones HA, Raggi VL (2006) Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 26:486–502

*Coletti DJ, Pappadopulos E, Katsiotas NJ, Berest A, Jensen PS, Kafantaris V (2012) Parent perspectives on the decision to initiate medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 22:226–237

*Corkum P, Rimer P, Schachar R (1999) Parental knowledge of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and opinions of treatment options: impact on enrollment and adherence to a 12-month treatment trial. Can J Psychiatry 44:1043–1048

*Cormier E (2012) How parents make decisions to use medication to treat their child’s ADHD: a grounded theory study. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 18:345–356

Cromer BA, Tarnowski KJ (1989) Noncompliance in adolescents: a review. J Dev Behav Pediatr 10:207–215

Cuffe SP, Moore CG, McKeown R (2009) ADHD and health services utilization in the National Health Interview Survey. J Atten Disord 12:330–340

Daly BP, Creed T, Xanthopoulos M, Brown RT (2007) Psychosocial treatments for children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychol Rev 17:73–89

Danforth S, Navarro V (2001) Hyper talk: sampling the social construction of ADHD in everyday language. Anthropol Educ Q 32:167–190

*Davis CC, Claudius M, Palinkas LA, Wong JB, Leslie LK (2012) Putting families in the center: family perspectives on decision making and ADHD and implications for ADHD care. J Atten Disord 16:675–684

*dosReis S, Butz A, Lipkin PH, Anixt JS, Weiner CL, Chernoff R (2006) Attitudes about stimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among African American families in an inner city community. J Behav Health Serv Res 33:423–430

*dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Soeken KL, Mitchell JW, Ellwood LC (2003) Parental perceptions and satisfaction with stimulant medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Dev Behav Pediatr 24:155–162

*Dreyer AS, O’Laughlin L, Moore J, Milam Z (2010) Parental adherence to clinical recommendations in an ADHD evaluation clinic. J Clin Psychol 66:1101–1120

Faraone SV, Biederman J, Zimmerman B (2007) An analysis of patient adherence to treatment during a 1-year, open-label study of OROS® methylphenidate in children with ADHD. J Atten Disord 11:157–166

Fitzcharles M, DaCosta D, Ware MA, Shir Y (2009) Patient barriers to pain management may contribute to poor pain control in rheumatoid arthritis. J Pain 10:300–305

Ford T, Fowler T, Langley K, Whittinger N, Thapar A (2008) Five years on: public sector service use related to mental health in young people with ADHD or hyperkinetic disorder five years after diagnosis. Child Adolesc Ment Health UK 13:122–129

*Gage JD, Wilson LD (2000) Acceptability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder interventions: a comparison of parents. J Atten Disord 4:174–182

*Gau SSF, Chen SJ, Chou WJ, Cheng H, Tang CS, Chang HL, Tzang RF, Wu YY, Huang YF, Chou MC, Liang HY, Hsu YC, Lu HH, Huang YS (2008) National survey of adherence, efficacy, and side effects of methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Taiwan. J Clin Psychiatry 69:131–140

*Gau SSF, Shen H, Chou M, Tang C, Chiu Y, Gau C (2006) Determinants of adherence to methylphenidate and the impact of poor adherence on maternal and family measures. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 16:286–297

*Graetz BW, Sawyer MG, Baghurst P, Hirte C (2006) Gender comparisons of service use among youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Emot Behav Disord 14:2–11

*Guevera J, Lozano P, Wickizer T, Mell L, Gephart H (2001) Utilization and cost of health care services for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 108:71–78

*Hong J, Novick D, Treuer T, Montgomery W, Haynes VS, Wu S, Haro JM (2013) Predictors and consequences of adherence to the treatment of pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Central Europe and East Asia. Patient Prefer Adherence 7:987–995

Huang H, Chao C, Tu C, Yang P (2003) Behavioral parent training for Taiwanese parents of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 57:275–281

Jensen PS, Kettle L, Roper MT, Sloan MT, Dulcan MK, Hoven C, Bird HR, Bauermeister JJ, Payne JD (1999) Are stimulants overprescribed? Treatment of ADHD in four U.S. communities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 38:797–804

Johnston C, Fine S (1993) Methods of evaluating methylphenidate in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: acceptability, satisfaction and compliance. J Pediatr Psychol 18:717–773

Kaiser NM, Pfiffner LJ (2011) Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for childhood ADHD. Psychiatr Ann 41:9–15

Kazdin AE (1981) Acceptability of child treatment techniques: the influence of treatment efficacy and adverse side-effects. Behav Ther 12:493–506

*Kelleher JK, Childs GE, Harmon JS (2001) Health care costs for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Econ Neurosci 3:60–63

*Krain AL, Kendall PC, Power TJ (2005) The role of treatment acceptability in the initiation of treatment for ADHD. J Atten Disord 9:425–434

Kutcher S, Aman M, Brooks SJ, Buitelaar J, van Daalen E, Fegert J, Findling RL, Fisman S, Greenhill LL, Huss M, Kusumakar V, Pine D, Taylor E, Tyano S (2004) International consensus statement on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and disruptive behaviour disorders (DBDs): clinical implications and treatment practice suggestions. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 14:11–28

*Leibson CL, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Ransom J, O’Brien P (2001) Use and costs of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Med Assoc 285:60–66

*Liu C, Robin AL, Brenner S, Eastman J (1991) Social acceptability of methylphenidate and behaviour modification for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 88:560–565

Mackner LM, McGrath AM, Stark LJ (2001) Dietary recommendations to prevent and manage chronic pediatric health conditions: adherence, intervention, and future directions. J Dev Behav Pediatr 22:130–143

MacNaughton KL, Rodrigue JR (2001) Predicting adherence to recommendations by parents of clinic-referred children. J Consult Clin Psychol 69:262–270

*Maniadaki K, Sonuga-Barke E, Kakouros E, Karaba R (2006) Parental beliefs about the nature of ADHD behaviours and their relationship to referral intentions in preschool children. Child Care Health Dev 33:188–195

*Marcus SC, Wan GJ, Kemner JE, Olfsan M (2005) Continuity of methylphenidate treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 159:572–578

*Miller AR, Lalonde CE, McGrail KM (2004) Children’s persistence with methylphenidate therapy: a population-based study. Can J Psychiatry 49:761–768

*Miltenberger RG, Parrish JM, Rickert V, Kohr M (1989) Assessing treatment acceptability with consumers of outpatient child behavior management services. Child Fam Behav Ther 11:35–44

*Monastra VJ (2005) Overcoming the barriers to effective treatment for attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a neuro-educational approach. Int J Psychophysiol 58:71–80

MTA Cooperative Group (1999) A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56:1073–1086

MTA Cooperative Group (2004) National Institute of Mental Health Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD follow-up: changes in effectiveness and growth after the end of treatment. Pediatrics 113:762–769

*Ohan JL, Johnston C (2000) Reported rates of adherence to medication prescribed for adolescents’ symptoms of ADHD. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 5:581–593

*Owens PL, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Poduska JM, Kellam SG, Ialongo NS (2002) Barriers to children’s mental health services. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:731–738

*Palli SR, Kamble PS, Chen H, Aparasu RR (2012) Persistence of stimulants in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 22:139–148

Pelham WE, Manos MJ, Ezzell CE, Tresco KE, Gnagy EM, Hoffman MT, Onyango AN, Fabiano GA, Lopez-Williams A, Wymbs BT, Caserta D, Chronis AM, Burrows-MacLean L, Morse G (2005) A dose-ranging study of a methylphenidate transdermal system in children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:522–529

Pelham WE, Wheeler T, Chronis A (1998) Empirically supported psychosocial treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Psychol 27:190–205

Perrin JM, Fluet C, Kuhlthau KA (2005) Benefits for employees with children with ADHD: findings from the collaborative employee benefit study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 26:3–8

*Power TJ, Hess LE, Bennett DS (1995) The acceptability of interventions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among elementary and middle school teachers. J Dev Behav Pediatr 16:238–243

*Ray GT, Levine P, Croen LA, Bokhari FAS, Hu T, Habel LA (2006) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children: excess costs before and after initial diagnosis and treatment cost differences by ethnicity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160:1063–1069

Reimers TM, Wacker DP, Koeppl G (1987) Acceptability of behavioral interventions: a review of the literature. School Psychol Rev 16:212–227

*Reimers TM, Wacker DP, Cooper LJ, DeRaad AO (1992) Clinical evaluation of the variables associated with treatment acceptability and their relation to compliance. Behav Disord 18:67–76

*Rieppi R, Greenhill LL, Ford RE, Chuang S, Wu M, Davies M, Abikoff HB, Arnold LE, Conners CK, Elliott GR, Hechtman L, Hinshaw SP, Hoza B, Jensen PS, Kraemer HC, March JS, Newcorn JH, Pelham WE, Severe JB, Swanson JM, Vitiello B, Wells KC, Wigal T (2002) Socioeconomic status as a moderator of ADHD treatment outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:269–277

Rostain A, Power T, Atkins M (1993) Assessing parents’ willingness to pursue treatment for children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32:175–181

*Rothenberger A, Becker A, Breuer D, Döpfner M (2011) An observational study of once-daily modified-release methylphenidate in ADHD: quality of life, satisfaction with treatment and adherence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 20:S257–S265

*Sawyer MG, Rey JM, Arney FM, Whitham JN, Clark JJ, Baghurst PA (2004) Use of health and school-based services in Australia by young people with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:1355–1363

*Sayal K, Goodman R, Ford T (2006) Barriers to the identification of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:744–750

*Sayal K, Taylor K, Beecham J (2003) Parental perceptions of problems and mental health service use for hyperactivity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42:1410–1414

Schachar R (2009) Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in children, adolescents, and adults. Contin Lifelong Learn Neurol 15:78–97

Scheffler RM, Hinshaw SP, Modrek S, Levine P (2007) The global market for ADHD medications. Health Aff 26:450–457

Schmitz MF, Filippone P, Edelman EM (2003) Social representations of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, 1988–1997. Cult Psychol 9:383–406

*Schneider BW, Gerdes AC, Haack LM, Lawton KE (2013) Predicting treatment dropout in parent training interventions for families of school-aged children with ADHD. Child Fam Behav Ther 35:144–169

Shen H, Edwards H, Courtney M, McDowell J, Wei J (2013) Barriers and facilitators to diabetes self-management: perspectives of older community dwellers and health professionals in China. IJNP 19:627–635

*Sitholey P, Agarwal V, Chamoli S (2011) A preliminary study of factors affecting adherence to medication in clinic children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Indian J Psychiatry 53:41–44

Staller JA (2006) Diagnostic profiles in outpatient child psychiatry. Am J Orthopsychiatry 76:98–102

*Stevens J, Harman J, Kelleher K (2005) Race/ethnicity and insurance status as factors associated with ADHD treatment patterns. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 15:88–96

Swanson J (2003) Compliance with stimulants for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: issues and approaches for improvement. CNS Drugs 17:117–131

*Swensen AR, Birnbaum HG, Secnik K, Marynchenko M, Greenberg P, Claxton A (2003) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: increases costs for patients and their families. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42:1415–1423

*Tarnowski KJ, Simonian SJ, Park A, Bekeny P (1992) Acceptability of treatments for child behavioral disturbance: race, socioeconomic status, and multicomponent treatment effects. Child Fam Behav Ther 14:25–37

*Thiruchelvam D, Charach A, Schachar RJ (2001) Moderators and mediators of long-term adherence to stimulant treatment in children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:922–928

Vanheusden K, van der Ende J, Mulder CL, van Lenthe FJ, Verhulst FC, Mackenbach JP (2008) The use of mental health services among young adults with emotional and behavioural problems: equal use for equal needs? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43:808–815

Vaughan BS, March JS, Kratochvil CJ (2012) The evidence-based pharmacological treatment of paediatric ADHD. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 15:27–39

Wells A, Lagomasino IT, Palinkas LA, Green JM, Gonzalez D (2013) Barriers to depression treatment among low-income, Latino emergency department patients. Community Ment Health J 49:412–418

*Wilson LJ, Jennings JN (1996) Parents’ acceptability of alternative treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord 1:114–121

*Zima BT, Bussing R, Tang L, Zhang L (2012) Do parent perceptions predict continuity of publicly funded care for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Pediatrics 131:S50–S59

Zindani GN, Streetman DD, Streetman DS, Nasr SZ (2006) Adherence to treatment in children and adolescent patients with cystic fibrosis. J Adolesc Health 38:13–17

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a research grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Acknowledgements are extended to the consulting group for this research: Dr. Alexa Bagnell, Dr. Andrea Kent, Dr. Renee Lyons, Ms. Margaret McKinnon, Dr. Marilyn MacPherson, Mr. David Jones, Mr. Dan Stephenson, Ms. Veronica Zentilli, and Mr. Rob and Mrs. Lavina Carreau. The authors would also like to thank Jennifer Mullane, Angela Mailman, Meredith Pike, and Adria Markovich for their editorial work and helpful comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corkum, P., Bessey, M., McGonnell, M. et al. Barriers to evidence-based treatment for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. ADHD Atten Def Hyp Disord 7, 49–74 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-014-0152-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-014-0152-z