Abstract

Introduction

Prior research suggests increased costs during the final months of life, yet little is known about healthcare cost differences between patients with heart failure (HF) who die or survive.

Methods

A retrospective claims study from a large US health plan [commercial and Medicare Advantage with Part D (MAPD)] was conducted. Patients were ≥18 years old with two non-inpatient or one inpatient claim(s) with HF diagnosis code(s). The earliest HF claim date during 1 January 2010–31 December 2011 was the index date. Cohort assignment was based on evidence of death within 1 year (decedents) or survival for >1 year (survivors) post-index. Per-patient-per-month (PPPM) and 1-year (variable decedent follow-up) costs (all-cause and HF-related) were calculated up to 1 year post-index. Cohorts were matched on demographic and clinical characteristics. Independent samples t tests and Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to examine cohort differences.

Results

Among patients with HF, 8344 survivors were 1:1 matched to decedents [mean age 75 years, 50% female, 88% MAPD; mean time to decedents’ death: 150 (SD 105) days]. Compared to survivors, more decedents had no pharmacy claims for HF-related outpatient pharmacotherapy within 60 days post-index (42.1% vs. 27.1%; p < 0.001). Decedents also incurred higher all-cause medical costs (PPPM: $21,400 vs. $2663; 1 year: $60,048 vs. $32,394; both p < 0.001) and higher HF-related medical costs (PPPM: $16,477 vs. $1358; 1 year: $39,052 vs. $16,519; both p < 0.001). Hospitalizations accounted for more than half of all-cause PPPM medical costs (54.6% for survivors, 84.3% for decedents).

Conclusion

Patients with HF who died within 1 year after an index HF encounter incurred markedly higher costs within 1 year (despite the much shorter post-index period) and PPPM costs than those who survived, with the majority of costs attributable to hospitalizations for both patient cohorts. There may be opportunities for improving outcomes in HF, considering higher use of pharmacotherapy and lower costs were seen among survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic heart failure (HF) is a progressive, incurable condition with an unpredictable course that affected nearly 6 million people in the USA in 2012 [1] and is expected to affect >8 million by 2030 [2]. Mortality due to HF is higher than for most forms of cancer, with 10.4% of patients with HF dying within 30 days of initial diagnosis, 22.0% within 1 year, and 50% within 5 years [3,4,5]. In addition, the US annual healthcare costs for HF were estimated at $31 billion in 2012 and are expected to rise to $70 billion by 2030 [2]. Because of high healthcare resource use associated with HF disease management, coupled with the high and increasing prevalence, HF represents a major and growing economic burden to the US healthcare system. Effectively managing rising healthcare costs for HF is an important public health goal for US payers given mounting budgetary constraints.

Prior studies on the general population have reported an increase in healthcare costs over the last year of life [6,7,8]. For example, for all disease states within a given year, Medicare spending was found to be sixfold higher for patients who died as compared to those who survived, with the main driver of higher costs among decedents being increasing hospitalization within a few months prior to death [9,10,11]. Although similar trends of higher end-of-life costs have been reported in patients with HF [12,13,14], there is scarce information comparing healthcare costs among decedents at end of life versus survivors within a given time period. Consequently, stakeholders may not consider or incorporate these costs into economic models and subsequent decision making related to treatments for HF.

Information on net end-of-life costs in decedents versus survivors with HF should provide a better understanding of the cost burden and serve as a useful input to US payers and policymakers evaluating the economic value of innovative treatments that reduce mortality in patients with HF. Furthermore, examining net end-of-life costs stratified by health plan type may provide added insights on end-of-life cost trends given the expected impact of differences in plan structure on overall costs. Therefore, the objective of this study was to compare total healthcare costs in a given year between patients with HF who died to those who survived, stratified by health plan type [commercial or Medicare Advantage with Part D (MAPD)].

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

This retrospective cohort study evaluated de-identified healthcare claims data for enrollees in commercial MAPD health plans. Pharmacy and medical claims and enrollment data were obtained from the Optum™ Research Database (ORD). The ORD provides a geographically diverse sample drawn from ~14 million commercial and 500,000 MAPD enrollees annually in the US. Mortality data from the Social Security Administration (SSA) death master files were merged with the claims data to supplement claims-based evidence of death. This study was conducted in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy rules.

Study Sample

Patients aged ≥18 years were included in the study sample if they had an HF diagnosis code (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 402.x1, 404.x1, 404.x3, 428.xx [15]) in any position on claim(s) for ≥1 inpatient hospitalization or ≥2 non-inpatient encounters (occurring on 2 different dates) during a 2-year identification period (1 January 2010 through 31 December 2011). The index date was defined as the date of the earliest qualifying claim with a diagnosis code for HF. Patients were required to be continuously enrolled in their health plan for 12 months prior to the index date (defined as the pre-index period) and for at least 30 days following the index date through the earliest occurrence of disenrollment, death, or 364 days post-index. Patients were excluded if specific data points were missing (unknown gender, geographic region, or health plan type) or if age at index was ≥65 years for commercial enrollees (costs are likely to be underreported in commercial enrollees eligible for Medicare). Patients were also excluded if the date of any claim was more than 45 days following the date of death to ensure no survivors were included in the death cohort. Two mutually exclusive cohorts were defined based on survival [survivors (no evidence of death, confirmed by the presence of any claims >12 months post-index)] or evidence of death (decedents) during the first 12 months following (and including) the index date.

Patient Characteristics and Costs

Demographic characteristics included age at index, gender, race/ethnicity, health plan type, and geographic region of residence based on US Census classification [16]. Clinical characteristics examined during the pre-index period included prior diagnosis code for HF, Quan-Charlson comorbidity score [17] (categorized as 0, 1–2, 3–4, ≥5), comorbid atrial fibrillation (AF), and comorbid diabetes. For patients with pre-index HF, guideline-directed HF-related outpatient pharmacotherapies (HFRx) [18] were captured for two periods: for 12 months pre-index for the subset of patients with pre-index HF and for 60 days post-index. For patients with no pre-index HF, HFRx was captured only during the 60 days post-index. The HFRx was characterized by treatment pattern (mono, dual, triple therapy or no presence of pharmacotherapy) during each of the two respective periods. The categories of HFRx included angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is), angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs), beta blockers, aldosterone receptor antagonists (AAs), and other pharmacotherapies (e.g., diuretics, hydralazine + isosorbide dinitrate, digoxin) (Supplemental Table S1).

Costs were recorded for up to the first 12 months (365 days) following (and including) the index date as cumulative costs. Patients in the decedent cohort died during the 12-month post-index period and therefore had a shorter post-index period than patients in the survivor cohort. Therefore, per-patient-per-month (PPPM) costs were computed to adjust for the variable post-index duration. Combined health plan-paid and patient-paid amounts were used to calculate all-cause and HF-related costs, reported as total costs (medical plus pharmacy), medical (combined ambulatory/office, emergency room services, inpatient hospitalization, and other medical), and pharmacy costs. The Consumer Price Index was applied to adjust costs to 2013 US dollars [19].

Analyses

To control for confounding, patients in the decedent cohort were hard matched in a 1:1 ratio to those in the survivor cohort. The goal of matching was to ensure study cohorts were as similar as possible in underlying patient characteristics, without eliminating clinical characteristics that were either direct or indirect drivers of HF-related or mortality-related costs. Matching variables were index year, age group, gender, health plan type (commercial or MAPD), geographic region, race/ethnicity, pre-index AF, pre-index diabetes, and whether the patient had no pre-index HF, pre-index HF diagnoses with pre-index HFRx, or pre-index HF diagnoses without HFRx. Patients who could not be matched were excluded from post-match analysis.

All study variables were presented as percentages for dichotomous and polychotomous variables and as means (+ SD) for continuous variables. Costs were compared between the decedent and survivor cohorts using Pearson’s chi-square test for dichotomous and polychotomous variables and independent samples t test for continuous variables.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2. Statistical significance was achieved at α = 0.05.

Results

A total of 229,056 patients with evidence of HF were identified. Applying additional inclusion criteria yielded a final study sample of 93,879 patients (12,650 decedents and 81,229 survivors; Fig. 1).

Study sample selection and attrition. HF heart failure, HFRx heart failure-related pharmacotherapy, ICD-9-CM International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification. Index date was defined as the date of the earliest qualifying claim with a diagnosis code for HF (ICD-9-CM codes 402.x1, 404.x1, 404.x3, 428.xx). Age was calculated as of index date; 8344 patients in the decedent cohort were hard matched (1:1) to those in the survivor cohort. Matching variables were index year, age group, gender, health plan type, geographic region, race/ethnicity, pre-index atrial fibrillation, pre-index diabetes, and whether the patient had no pre-index HF, pre-index HF diagnoses with pre-index HFRx, or pre-index HF diagnoses without HFRx

Patient Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. The unmatched sample included 12,650 decedents and 81,229 survivors. Statistically significant differences (p < 0.001) were noted for most pre-match demographic characteristics, other than gender (Table 1). Before matching, a higher percentage of decedents had pre-index HF (Table 2). Among individuals with pre-index HF, a lower percentage of patients in the decedent cohort had pre-index HFRx [85.1% (4114 of 4836)] as compared with the survivor cohort [88.0% (23,445 of 26,636), p < 0.001]. The pre-match decedent cohort also included a higher percentage of patients with AF and higher percentages with elevated (i.e., 3–4, ≥5) Quan-Charlson comorbidity scores. A higher percentage of pre-match decedents had no evidence of HFRx within 60 days post-index, and for each HFRx regimen, other than monotherapy AA, lower percentages of decedents were receiving each regimen than their survivor counterparts.

After matching, 8344 patients were included in each cohort. The matched decedent cohort had higher percentages with elevated (i.e., 3–4, ≥5) Quan-Charlson comorbidity scores. However, the patterns of HFRx within 60 days post-index were similar between the cohorts before and after matching (Tables 1, 2).

Cumulative Healthcare Costs

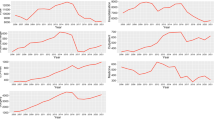

The post-index cumulative all-cause and HF-related healthcare costs for matched cohorts are displayed in Table 3 and Fig. 2. Costs are described by survival status both for the full sample (non-stratified) and stratified by health plan type (commercial, MAPD). Among the full sample, mean (SD) total all-cause costs (medical plus pharmacy) for decedents were 70.3% higher than for survivors [decedents: $62,036 ($112,486); survivors: $36,426 ($60,845), p < 0.001]. Decedents’ HF-related medical costs were more than double the costs incurred by survivors [$39,052 ($95,768) vs. $16,519 ($44,755), p < 0.001]. Hospitalizations accounted for the largest component of all-cause total costs for each cohort, with the percentage of costs due to hospitalizations approximately 25-percentage points higher in decedents compared to survivors (73.4% for decedents vs. 48.5% for survivors). Hospitalizations similarly accounted for the largest component of HF-related medical costs in each cohort, with a 10-percentage point difference between decedents and survivors (92.0% for decedents; 82.0% for survivors).

Cumulative healthcare costs, matched decedent and survivor cohorts, non-stratified and by health plan type. HF, heart failure. All patients in the survivor cohort were living at 12 months post-index; patients in the decedent cohort died within 12 months post-index (mean post-index time to death for matched cohort: 150 days). Comparisons of HF-related medical costs and outpatient pharmacy costs between survivors and decedents were statistically significant at p < 0.001. Statistical comparisons were not performed for non-HF medical costs. Percentages listed demonstrate proportions of total all-cause costs attributable to each type of cost

When stratified by health plan type, cumulative costs were two- to fourfold higher among commercial enrollees than MAPD enrollees (Table 3). Comparing cumulative costs between decedents and survivors within each health plan type, statistically significant differences were detected for nearly all cost categories. Among commercial enrollees, 80.1% of total all-cause costs [$179,095 ($266,618)] for decedents were due to hospitalizations [$143,375 ($253,789)], whereas hospitalizations accounted for 57.9% of total all-cause costs for survivors [total: $69,130 ($138,429); hospitalizations $40,042 ($120,935)]. For MAPD enrollees, hospitalizations accounted for a slightly lower proportional contribution to total all-cause costs for each cohort [decedents total: $46,673 ($54,394); $32,693 (70.0%) due to hospitalizations; vs. survivors total: $32,134 ($38,945); $14,737 (45.9%) for hospitalizations].

Among the commercially enrolled, decedents incurred 2.6-fold the total all-cause costs and 3.2-fold the HF-related medical costs as compared to survivors (Fig. 2). Within the commercial sample, costs were higher across each all-cause healthcare cost type for those who died versus survived, with the exception of pharmacy costs [decedents: $3707 ($10,065) vs. survivors: $5724 ($8236), p < 0.001]. HF-related medical costs were 3.2-fold higher for those who died [$116,603 ($238,486) vs. survivors: $36,964 ($109,688); p < 0.001] and represented 65.1% and 53.5% of total all-cause healthcare costs, respectively. Hospitalizations accounted for 96.3% and 88.1% of HF-related medical costs for decedents and survivors, respectively. Costs attributed to HF-related ambulatory care were lower for decedents [$1789 ($7576) vs. survivors $3555 ($13,239); p < 0.001].

Among MAPD enrollees, decedents incurred 1.5-fold higher total all-cause costs as survivors and 2.1-fold higher HF-related medical costs (Fig. 2). Among MAPD enrollees, costs were also higher for decedents than survivors for all healthcare cost types with the exception of higher ambulatory care [$4051 ($9322) vs. $7287 ($12,720); p < 0.001] and pharmacy costs [$1762 ($3620) vs. $3809 ($6109); p < 0.001] among survivors. HF-related medical costs [decedent: $28,875 ($45,000) vs. survivor: $13,835 ($25,026), p < 0.001], represented 61.9% and 43.1% of total all-cause costs for decedents and survivors, respectively, with the majority (89.7% and 79.8%) of HF-related medical costs being attributable to hospitalizations.

Per-Patient-Per-Month Healthcare Costs

The post-index PPPM all-cause and HF-related healthcare costs for matched cohorts are displayed in Table 4 and Fig. 3, accounting for variable lengths of the post-index period. Decedents had higher cumulative costs, despite the survivors having a longer time horizon for cost capture. The PPPM costs in all resource categories were higher for decedents than survivors; when stratified by health plan type, there were isolated exceptions (HF-related ambulatory costs for commercial enrollees, all-cause pharmacy costs for MAPD enrollees) (Table 4).

Per-patient-per-month healthcare costs, matched decedent and survivor cohorts, non-stratified and by health plan type. HF, heart failure. All patients in the survivor cohort were living at 12 months post-index; patients in the decedent cohort died within 12 months post-index (mean post-index time to death for matched cohort: 150 days). Comparisons of HF-related medical costs and outpatient pharmacy costs between survivors and decedents were statistically significant at p < 0.001. Statistical comparisons were not performed for non-HF medical costs. Percentages listed demonstrate proportion of total all-cause costs attributable to each type of cost

For commercial enrollees, PPPM total all-cause costs were 11.6-fold higher for patients who died [$66,084 ($122,848) vs. survivors: $5682 ($11,378); p < 0.001] (Fig. 3). HF-related costs were 17.1-fold higher for those who died [$52,050 ($121,054) vs. survivors: $3038 ($9015), p < 0.001], representing 78.8% and 53.5% of total all-cause costs.

Among MAPD enrollees, PPPM total all-cause costs were sixfold higher among decedents versus survivors. All resource categories for all-cause costs were higher (p < 0.001) for decedents versus survivors, with the exception of all-cause pharmacy costs, which did not differ. PPPM HF-related medical costs were 10.4-fold higher for the patients who died (total: $11,808 ($23,074) vs. survivors: $1137 ($2057); p < 0.010), representing 74.1% and 43.1% of total all-cause healthcare costs. HF-related hospitalizations accounted for most (93.9% and 79.9%) of the HF-related costs.

Discussion

Heart failure imposes a considerable cost burden on society with annual US spending on disease management estimated at $32 billion in 2012 and projected at $70 billion by 2030 [2]. Effectively managing these high and rising costs for HF has therefore become an important public health goal for US payers and other stakeholders given mounting budgetary constraints. Although prior studies have reported an escalation of the cost burden in decedents with HF prior to death [12,13,14], none performed relative comparisons with costs in survivors, making it difficult to quantify the impact of end-of-life care on HF costs. This study compared total healthcare costs in a given year between matched cohorts of decedents and survivors separately for commercial and MAPD plan enrollees. Such cost estimates will provide a better understanding of the end-of-life cost burden in patients with HF and may serve as input in economic evaluations of innovative treatments with a mortality benefit.

After cohort matching, decedent patients with HF were found to incur mean all-cause healthcare costs from index HF diagnosis until death (variable average post-index period of 5 months) that were approximately twice as large as mean all-cause 12-month costs for HF survivors, this despite having a mean post-index period that was 59% shorter (matched cohorts). Decedents incurred mean costs of $62,036 as compared to 12-month costs of $36,426 for survivors. The highest percentage of costs across both cohorts was for hospitalizations. The percentage of total costs attributed to hospitalizations was higher in decedents (73.4% of total) than survivors (48.5% of total). These findings are consistent with prior studies reporting hospitalization costs that accounted for 70.4% [12] and 56.1% [14] of end-of-life costs among patients with HF. These results suggest a greater frequency of all-cause hospitalizations and expensive inpatient treatments at the end of life, among patients with HF, which is not surprising given the anticipated higher morbidity and health complications in patients with HF close to death.

A similar trend of higher costs among decedents with HF was observed for HF-related healthcare costs. Decedents had HF-related costs more than twice those of survivors, incurring a mean $39,052 versus $16,519 for survivors over the post-index period. As with all-cause cost estimates, hospitalizations accounted for the highest percentage of costs in both decedents and survivors. Of all cost categories, only HF-related ambulatory costs and all-cause pharmacy costs were lower in the decedent cohort than the survivor cohort. It is unclear whether these findings suggest a shift from ambulatory care to hospital or palliative care at the end of life in patients with HF or, conversely, are reflective of a healthier survivor cohort with higher ability to seek ambulatory care.

After stratification by health plan type, the trend of considerably higher mean costs in decedents than survivors remained; however, the magnitude of difference in costs between decedents and survivors was higher in commercial plans (2.6-fold higher) than MAPD plans (1.5-fold higher). This finding may highlight known differences in the cost structure between both plan types, with care reimbursed at a higher rate in commercial plans relative to MAPD plans. In addition, findings may also reflect differences in the HF severity level across both plan types; however, reliable indicators of HF severity including New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class and ACC/AHA staging were not available in the study data set to evaluate this further.

PPPM costs calculated to adjust for variable post-index periods between decedents and survivors showed all-cause PPPM costs were sevenfold higher in decedents (costs calculated based on mean post-index period of 150 days until death) than survivors (365-day post-index period). Upon stratification by health plan type, PPPM costs in decedents compared with survivors were 12-fold higher among commercial enrollees and 6-fold higher among MAPD enrollees. Similar trends were observed for PPPM HF-related costs. The PPPM findings again reinforce the high cost burden associated with mortality in patients with HF and could be leveraged for economic assessments of HF disease management interventions, including pharmacotherapies that have a mortality benefit.

Limitations

This study utilized administrative claims data that are not designed for research purposes and are subject to possible inaccuracy. Evidence of a condition was identified using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and may not necessarily represent confirmed diagnoses; however, codes used in the current study have been used in prior research to identify the same specific conditions [15, 17, 20, 21].

Also, it is possible patients identified as having “de novo HF” during the identification period may have had diagnosis codes for HF more than 1 year prior to index date (before the pre-index period), but this was expected to be a rare occurrence. Incorporating external mortality data from the SSA death master files in the current study made it possible to more accurately determine the timing of all-cause deaths. However, the SSA death master file has known limitations due to data degradation starting in late 2011. Following November 2011, several states were no longer providing death information to the SSA, making their mortality records incomplete. As a result, absolute death rates will be underestimated; nevertheless, relative outcomes among patients who died versus survived should remain unbiased.

Information on ejection fraction, NYHA Functional Classification, biomarkers, smoking status, and body mass index were unavailable for this study, all of which may potentially impact healthcare costs. Specific indicators of severity are not available among the claims data; the absence of this information potentially confounds the analysis. However, a prior study found similar inpatient resource utilization in the first year post HF hospitalization between patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction versus preserved ejection fraction, suggesting identification in either ejection fraction category may have limited influence on costs [22]. Cost estimates from this study were derived for a majority MAPD sample and so caution is advised when generalizing to patients with HF in other care settings. Finally, the matching procedure did not create balanced cohorts across all demographic and clinical variables, which might bias assessment of costs. However, AF and diabetes, two very important clinical factors known to impact costs [23,24,25], were among variables matched between cohorts.

Conclusions

This study compared total healthcare costs in a given year between matched cohorts of HF decedents and survivors separately for commercial or MAPD plan enrollees. Overall, decedents incurred substantially higher costs from index to death, as compared to survivors, despite having a mean post-index period that was 59% shorter than the survivors (matched cohorts). The largest percentage of costs across both patient cohorts was attributed to hospitalizations. For both commercial and MAPD enrollees, similar trends of higher costs among decedents were found; however, the magnitude of difference in costs between both cohorts was higher in commercial plans (2.6-fold higher) than MAPD plans (1.5-fold higher). The findings from the current study offer useful insights on end-of-life cost burden in patients with HF and provide cost estimates that could be useful in economic evaluations of innovative HF treatments. There may be opportunities for improving outcomes in HF considering the higher use of pharmacotherapy and lower costs seen among survivors.

References

National Center for Health Statistics. Mortality multiple cause micro-data files, 2011. NHLBI Tabulations. 2011. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/Vitalstatsonline.htm#Mortality_Multiple. Accessed 30 Nov 2015.

Heidenreich PA, Albert NM, Allen LA, et al. Forecasting the impact of heart failure in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):606–19.

Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(7):1016–22.

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127(1):e6–245.

Howlader N, Noone, A. M., Krapcho, M., et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2015. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975-2012/. Accessed 30 Nov 2015.

Scitovsky AA. “The high cost of dying”: what do the data show? 1984. The Milbank quarterly. 2005;83(4):825–41.

Halek M, Rosenberg M, Conway J, Valliappan V. Implications of the Cost of End of Life Care: A Review of the Literature. Society of Actuaries University of Wisconsin-Madison. December 2012. Available at https://www.soa.org/files/research/projects/research-health-soa-eol-final.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2015.

Tanuseputro P, Wodchis WP, Fowler R, et al. The health care cost of dying: a population-based retrospective cohort study of the last year of life in Ontario, Canada. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121759.

Hoover DR, Crystal S, Kumar R, Sambamoorthi U, Cantor JC. Medical expenditures during the last year of life: findings from the 1992–1996 Medicare current beneficiary survey. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1625–42.

Riley GF, Lubitz JD. Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(2):565–76.

Calfo S, Smith J, Zezza M. Last year of life study. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary. 2012. Available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/ActuarialStudies/Last_Year_of_Life.html. Accessed 30 Nov 2015.

Kaul P, McAlister FA, Ezekowitz JA, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among patients with heart failure in Canada. Arch Int Med. 2011;171(3):211–7.

Dunlay SM, Redfield MM, Jiang R, Weston SA, Roger VL. Care in the last year of life for community patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(3):489–96.

Unroe KT, Greiner MA, Hernandez AF, et al. Resource use in the last 6 months of life among medicare beneficiaries with heart failure, 2000–2007. Arch Int Med. 2011;171(3):196–203.

Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, et al. Patterns of hospital performance in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2(5):407–13.

United States Census Bureau. Census regions and divisions of the United States. 2015. Available at http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2015.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–9.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147–239.

United States Department of Labor. Consumer Price Index. Chained Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers (C-CPI-U) 1999–2013, Medical Care. In: United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2014. Available at http://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/surveymost?su. Accessed 30 Nov 2015.

Estes NAM 3rd, Halperin JL, Calkins H, et al. ACC/AHA/Physician Consortium 2008 clinical performance measures for adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Circulation. 2008;117(8):1101–20.

Chen G, Khan N, Walker R, Quan H. Validating ICD coding algorithms for diabetes mellitus from administrative data. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89(2):189–95.

Nichols GA, Reynolds K, Kimes TM, Rosales AG, Chan WW. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(7):1088–92.

Bogner HR, Miller SD, De Vries HF, Chhatre S, Jayadevappa R. Assessment of cost and health resource utilization for elderly patients with heart failure and diabetes mellitus. J Card Fail. 2010;16(6):454–60.

Ziaeian B, Sharma PP, Yu T-C, Waltman Johnson K, Fonarow GC. Factors associated with variations in hospital expenditures for acute heart failure in the United States. Am Heart J. 2015;169:282–9.

Smith DH, Johnson ES, Blough DK, Thorp ML, Yang X, Petrik AF, Crispell KA. Predicting costs of care in heart failure patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:434.

Acknowledgements

This study and article processing charges were funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

The authors thank Chun-Lan Chang, PhD, for contributions to data interpretation and manuscript development. Medical writing support was provided by Caroline Jennermann, MS, of Optum, funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp.

Disclosures

At the time of the study, Engels N. Obi was an employee of Rutgers University providing services to Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corp. (NPC) and was reimbursed for travel to present research; he is now an employee of NPC. He has no conflicts to disclose.

Jason P. Swindle is an employee of Optum, Inc., which was contracted by NPC to perform the study; employment was not contingent upon this funding. He has no conflicts to disclose.

Stuart J. Turner is an employee of NPC and has no conflicts to disclose.

Patricia A. Russo provided consulting services to NPC as an employee of DataMed Services, Inc., but she is a current employee of NPC. She has no conflicts to disclose.

Aylin Altan is an employee of Optum, Inc., which was contracted by NPC to perform the study; employment was not contingent upon this funding. She has no conflicts to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy rules.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/5627F0605288248B.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Obi, E.N., Swindle, J.P., Turner, S.J. et al. Healthcare Costs Among Patients with Heart Failure: A Comparison of Costs between Matched Decedent and Survivor Cohorts. Adv Ther 34, 261–276 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0454-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0454-y