Abstract

Coccidioidomycosis is an endemic systemic mycosis of the western hemisphere that has acquired mayor relevance after a raise in cases in the recent years. Two species, Coccidioides immitis and C. posadasii are recognized as the causative agents of this disease that, in principle, primarily affects the lungs. Extra pulmonary cutaneous forms have been more frequently reported and its manifestations present a vast clinical spectrum that resembles subcutaneous mycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis or even skin cancer. The interaction of the host and its immune response against the fungus and its pathogenic mechanism play a major role in the evolution, clinical and histopathological aspects and finally in the resolution of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coccidioidomycosis is an endemic disease of the American continent that is located mainly in the area between the USA and Mexico, as well as important regions of Latin America [1]. It can be considered as a reemerging illness because of the marked increase in cases over the last decades and the recent awareness of the extension of the endemic zone towards northern USA [2].

The etiologic agent is a pathogenic, soil-dwelling, dimorphic fungus from the genus Coccidioides. There are two recognized species: Coccidioides immitis and C. posadasii. Coccidioides spp. has the ability to harm various organs, although generally the target becomes the lungs due to the inhalation of arthroconidia, the mycelial and saprophytic form of the fungus. The majority of cases present pulmonary involvement with mild or moderate respiratory symptoms that resolve without treatment [3•].

Some patients develop pneumonia and require treatment, and a very scarce few progress to disseminated pulmonary forms. In secondary forms other organs like the central nervous system; lymphatic nodes, skin, bones and joints can become affected. There is also a primary cutaneous disease, which is a clinical form without the initial pulmonary involvement that occurs as a result of the traumatic inoculation through the skin. It is very rare and the morphology is very diverse [4]. The skin, being a very accessible organ, is where the disease can be frequently diagnosed. The degree of severity depends on the genetic predisposition and the immune status of the host.

Epidemiology

Approximately 60 % of coccidioidomycosis cases are asymptomatic and 40 % cause a mild influenza-type febrile respiratory disease that may progress to pneumonia and on rare occasions may become disseminated. In pulmonary coccidioidomycosis the severity is usually mild or moderate and on the least of cases it can progress to a severe and or disseminated disease. Extra pulmonary infection is observed in 1 to 5 % of infected patients; Skin and soft tissue coccidioidomycosis can present in 15 to 67 % of those with disseminated infection [5].

The main focus of the disease is located in the southwestern United States. It is estimated that 150,000 infections by Coccidoides spp. are produced annually in this country. In California there was a rise in the number of hospitalizations caused by coccidioidomycosis, from 3.2 to 8.6 for every 100 inhabitants between 2000 and 2011. Of that total of 25,217 hospitalized patients with coccidioidomycosis, 163 (0.6 %) corresponded to cases of extrapulmonary primary coccidioidomycosis [6]. In the USA, there has also been an increase in the incidence of the infection from 37.3 cases per 100,000 inhabitants from the period between 1998 and 2011 [7•]. In Arizona and California, there has been a high incidence of hospitalizations from disseminated coccidioidomycosis on black ethnic groups [8]. During pregnancy the risk of dissemination to the skin increases dramatically [9].

Besides the increase in cases in these endemic regions, an extension of the range of the affected zone has also been observed [2]. Recently in the northern State of Washington, a location that is unknown to be endemic, 3 cases of coccidioidomycosis have been reported, one of them with primary cutaneous infection [10]. The fungus that was subsequently isolated from the soil had identical genome as the one isolated from the patient’s lesion [11•].

In 1968, a total of primary cutaneous cases reported were less than 20 [12].Even though the true frequency of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis is unknown, in the last years there has been a notable report of cases of disseminated and primary cutaneous, on endemic regions [13, 14, 15•, 16], as well as in other non-endemic continents where the disease has been exported like Asia and Europe [17–20].

Etiopathogenesis

The Coccidioides genus belongs to phylum Ascomycota, order Onygenales. There are two known species, C. immitis and C. posadasii, both with similar characteristics and highly pathogenic for men and other mammals. It is a thermally dimorphic fungus, resident of the soil where it develops as a saprophyte in a filamentous form. The filaments are septated and elongated and composed of arthroconidia that resembles a barrel that measures 3 × 6 μ [21••]. In this phase, it can survive for years and disseminate through the air and infect by inhalation of the propagules [22•]. In exceptional cases the conidia are introduced through the skin by trauma, a thorn or splinter or at the laboratory in an accidental manner. It has also been reported after a cat bite [23].

Once it invades the host tissues, and the conditions of its habitat change, a rise in temperature and CO2 concentration, the fungus suffers a phenotypic change to spherule. The arthroconidia becomes rounded and enlarges to become a spherule. Within days the spherules increase cellular division and maturation and transform into big septated cells that measure between 10 and 80 μ, afterwards they produce a high amount of endospores measuring from 1 to 2 μ; furthermore they break and liberate spores that will infect underlying tissues. The endospores become bigger until they form new spherules, and thus, a new parasitic phase of the cycle that will disseminate the infection [24•].

During the first days of the infectious cycle, the innate cellular immunity tries to remove the fungus by phagocytosis of neutrophils. But these cells can only eliminate a certain quantity of arthroconidia. The recognition of the pathogen by the antigen presenting cells (APC) that includes dendritic cells promotes a cellular response. Pro-inflammatory mediators of the immune response Th1 like TNFα, MIP-2, and IL- with cytokines IL12 and INFƔ and TH 17 response with cytokines IL 23, IL 17, IL 22 IL 1b, with an evident increment of the cellular immune response [25]. On the other hand, disseminated coccidioidomycosis has been found in two patients with deficiency of the sub-unit 1β of the receptor for IL12, this demonstrates the importance of this defense mechanism [26].

Coccidioides sp., presents evasive methods of the host’s immune response like the thermal phenotypic change that was mentioned before. The fungus also escapes the oxidative defense by resisting phagocytosis and by producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) because of failure of the phagosome-lysosome fusion. The big size of the spherule can limit the engulfing by neutrophils and at the same time the intracellular growth of the spherule probably disintegrates the neutrophil cell. The alkalinization of the extra cellular matrix (ECM) also avoids contact with neutrophils, and the consequent destruction by degranulation. The fungus avoids the recognition and phagocytosis by digesting an antigen of the spherule wall (SOWgp) [27]. The endospores do not express this antigen (SOWgp) thus avoiding the cellular immune response. As well as, the liberation of a great quantity of grouped endospores, the production of biofilms envelops and protects against phagocytosis also. [24•, 25, 28].

Coccidioides spp., presents and extensive family of genes, like the family of deuterolysines and metalloproteinase M35, proteases that can have the capacity of digesting the tissues locally and become an important factor in the pathogenesis of the disease [21••, 29, 30]. Urease is another Coccidioides enzyme that induces cell damage and can contribute to the dissemination of the infection and severity of the illness. These proteolytic enzymes seem to be the main participants in the virulence of the fungus and the lesion of the host [31, 32].

Patients with coccidioidomycosis show both cellular and humoral immune response. In severe or disseminated disease a strong humoral response with high complement and IgG antibodies with a low response of late hypersensitivity is frequently observed.

In contrast, in asymptomatic disease or in primary cutaneous coccidiodomycosis, a strong delayed-type hypersensitivity(DTH) response and a weak humoral response with low levels of complement and antibodies is expected [24•].

Clinical Aspects

The spectrum of clinical manifestations of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis is very wide; from a pink solitary papule to variegated presentations that show different sizes, appearance, multiple shapes, some very extensive and disseminated [33, 34].The diversity of lesions in the skin depends on the type of inoculation, location, time evolution and mainly the host’s immunity.

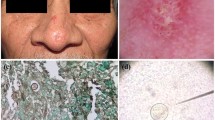

The clinical manifestations of the disease on the skin can be divided in (a) reactive eruptions from the primary pulmonary infection without detectable microorganisms, like erythema nodosum, erythema multiform, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, acute generalized exanthema, and sweet syndrome and (b) cutaneous lesions that are inhabited, that will be discussed in this article [35–37] (Fig. 1a).

a Generalized exanthem and erythema multiform type lesions in a patient with fever and dry cough. b Disseminated coccidioidomycosis of the skin with multiple lesions. c Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis in a girl who presents an exophytic verrucous lesion in the plantar region (Detail). d KOH exam with spherules with endospores and thick wall. e Spherule inside a multinucleated giant cell (H&E), (Courtesy of Dr. Rodarte J). f Early development of a cotton like colony of C. posadasii in DTM

Disseminated Cutaneous Coccidioidomycosis

It is caused by pulmonary infection with dissemination hematogenous spread to the skin, mucous membranes and lymphatic nodules. As a consequence to infection near the neck, supraclavicular or axillar regions you can observe lymphadenopathy and abscess or gummas [38]. These lesions are often seen with fistulas, ulcers, and scars with a relapsing course very similar to colicuative tuberculosis. In disseminated skin disease, single, multiple, or miliar, papules, pustules nodules, verrucous plaques, scabs and ulcers may be observed [14, 39] (Fig. 1b). It can present in any region of the body, although it has been in the head and face in 30 % of 104 patients that had positive biopsy [40]. Sometimes erythema, telangiectasia and facial atrophy that can be mistaken for discoid lupus, facial granuloma or psoriasis may be observed [41]. In the mucous membranes the lip and tongue has ulcers as its manifestation [12, 42].

Skin infection can also be associated with osteoarticular dissemination; it begins with flogosis and ends with bone infection or fistula formation and drainage of serous and purulent material in articulations like the knee [15•, 43].

Primary Cutaneous Coccidioidomycosis

It begins directly on the injured skin once the fungus is introduced by trauma. It begins with a papule or nodule, like a chancre at the point of contact. It then extends by contiguity; it forms a plaque with multiple tiny confluent nodules with some pustules that are covered by serohematic scab. It can also form a localized granulomatous, ulcerated and verrucous plaque. On the centrofacial region, nasal tip, ala or cheek there may be plaques 1 to 3 cm in diameter with papules, granulomatous nodules that can be ulcerated and covered with scabs [44, 45].

In fixed cutaneous forms, the growth pattern of the lesion is by contiguity; another form of extension is a small satellite lesion on the periphery after the primary lesion found at the inoculation site. But the most characteristic form of primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis is a lymphangitic sporotrichosis type of lesion with an inoculation site chancre, regional lymphatic dissemination with various staggered nodular or gumma lesions that follow a lineal and proximal course [4, 46]. Although the most common site in the primary cutaneous infection are the extremities, in the last years there have been more reports of primary cases on the face [15•, 16, 44].

Because of its morphologic distribution, cutaneous coccidioidomycosis can resemble cutaneous tuberculosis, syphilis, fixed or lymphangitic sporotrichosis, cancer, sarcoidosis, lepromatous leprosy, mycosis fungoides, and this is why it is justified tic al it “the other great imitator” [41, 47–50] (Fig. 1c).

In order to determine the cases as primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis or secondary to pulmonary infection, Wilson, Smith and Plunkett [51], in 1953 proposed the following criteria that can be taken into consideration:

-

1.

No history of pulmonary disease that precedes the lesion.

-

2.

History of inoculation by rupture of the skin in the initial lesion

-

3.

Short incubation period of 1 to 3 weeks.

-

4.

Primary chancre like lesion (a firm painless nodule or an ulcerated plaque).

-

5.

Early positive precipitation reaction

-

6.

Positive coccidioidin intradermal reaction

-

7.

Negative or low titles of early complement fixation

-

8.

Lymphangitis, lymphadenopathy and nodules on the site of drainage

-

9.

Spontaneous healing of chancre in a few weeks

Locus Minoris Resistentiae

When there is a manifestation of coccidioidomycosis on the skin, we must remember the locus minoris resistentiae reactivation phenomena in coccidioidomycosis. It has been described that extra pulmonary lesions can occur from a relatively dormant primary pulmonary focus without association of a recent respiratory infection. Coccidioides sp. can be on the bloodstream at the moment of a cutaneous lesion and may infect the site or it can be deposited on the tissue and on a posterior aggression to the skin it may develop and expand and disseminate the disease [52].

DiCaudo comments that in those cases, if the patient presents mild pulmonary symptoms or they are absent, it can be difficult to differentiate between a disseminated and a cutaneous primary lesion [34].The history of localized trauma at the affected site does not discard the possibility of a disseminated infection. It is important, although complicated to differentiate between these forms. One example is on a localized infection on the scalp, face or neck area where there may or may not be accompanied by regional lymphadenopathy. In many of these cases the positive intradermal reaction with coccidioidin in the primary forms and high titles of complement fixation in the disseminated forms can guide the clinician and classify the disease [34].

Recently the term immunocompromised district has been suggested in dermatology, like in the locus minoris resistentiae condition, to describe a vulnerable site that can develop secondary disease because of certain factors like physical damage by burns, UV radiation, trauma, varicella zoster virus infections that can be considered in these cutaneous manifestations of coccidioidomycosis [53, 54].

Diagnosis

The gold standard in the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis is isolation of the fungus in culture or when it is identified in tissues and specimens of the host by observing the typical parasitic forms: spherules and endospores, although atypical parasitic forms may be seen; septated hyphae, mycelium or even pleomorphic forms [55•].

Coccidioides sp, can be identified directly from the sputum, secretions, bronchoalveolar lavage, pus, or squame of cutaneous lesions [56, 57] under direct microscopic examination with saline solution, potassium hydroxide (KOH) or calcofluor on fluorescent microscope (Fig. 1d). Aspiration with fine needle and Papanicolaou stain can be useful in some disseminated cases, in abscesses, or in lymphatic nodes [58–60].

Tissues show the microorganism in hematoxilin and eosin stain (H&E), periodic acid Schiff stain, or silver methenamine of Grocott. The typical parasitic form has spherical cells with double wall within an inflammatory reaction that can vary and is frequently granulomatous; it is possible to localize the spherules in the center of the dense infiltrate of neutrophils, histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells and even inside multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 1e); there are grouped lymphocytes T and B surrounding the granulomas with necrosis as a response to the fungus. The epidermis is commonly hyperplasic, ulcerated with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and sometimes there may be transepidermic elimination of the fungus [61, 62].

The following histologic inflammatory patterns have been found: suppurative, lymphoplasmacytic, sarcoidal, eosinophillic and necrotizing granuloma as well as neutrophilic infiltrate without granuloma [40].

The histological differential diagnosis of the spherules is with other parasitic organisms, algae, bacteria, or other fungi of similar form and size like Criptococcus, Blastomyces, Emmonsia, Rinosporidium, Prototheca, even with pollen grains. In immunocomprimised patients, there may be a coexistence of these elements [60–63].

Coccidioides sp. grows easily at room temperature in the course of a week, in culture media like dextrose agar, simple Sabouraud and with antibiotic, even in dermatophyte test medium (DTM) (Fig. 1f). It develops like a white filamentous colony, sometimes villous at the beginning, and humid and membranous that finally covers all the culture media and turns from white to dirty white. The microscopic examination a mycelia may be seen that is made up of thin, septated, ramified filaments with rectangular articulate conidia alternating with empty spaces: arthroconidia with rexolisis phenomenon. The Coccidioides sp., culture must always be planted in a biosafety hood level 3 [64].

The intradermal reaction with coccidioidin may help in the diagnosis with it the immune response of delayed hypersensitivity of the patient that has been in contact with the fungus can be titrated. In 2011, the FDA approved a reformulated product, an antigen obtained from the C. immitis spherule to be used clinically [65, 66].

Serology and Molecular Markers

Serology is of great utility in the diagnosis and confirmation of the disease. These include traditional methods of antibody detection by tube precipitation (TP), it detects immunoglobulin M and it appears in early phases of the infection and complement fixation (CF), where IgG reacts and appears later to the infection. This is a quantitative test and has predictive value, the titles decrease at the time of recovery. High IgG titles suggest dissemination more than primary cutaneous infection. Immunodifussion ID test is more specific and useful in the confirmation of other serologic tests. Enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is useful in cases of early infection and has more sensitivity. The false negative results do not exclude infection, especially in early phases and immunocompromised patients. The sensitivity can increase with diverse techniques or if the tests are repeated in one month [22•, 58, 67, 68].

Recently a serological immune signaling technique has been reported based on a selection of peptides; this test has accomplished a distinction between infection and non-infection with 100 % sensitivity and 97 % specificity [69••].

There are molecular techniques to detect and identify Coccidioides sp. based on amplification signaling methods that can be done with hybridization of nucleic acid that can be used to confirm and identify the fungus in culture or tissue. Other techniques based on amplification of nucleic acid with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for example, the real time PCR RT-PCR where the technique can be done in 4 h in fresh tissue, secretions and fluids. These tests are more sensitive and specific that conventional methods to detect Coccidioides spp. but with certain inconveniences: they are not easily available and some require validation [70–72].

Treatment

In disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis and primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis, without systemic nervous system compromise, the treatment can be ambulatory with 400 mg of itraconazole daily or fluconazole 400 mg daily, for 1 year approximately. This depends on clinical and serological evaluation [73, 74].

In non-meningeal disseminated disease or during pregnancy on the first trimester treatment is based on intravenous amphotericin B (especially lipid and liposomal formulations), it is preferable to use lipidic amphotericin B, which may be administered 3–5 mg/kg/day. Azoles should be avoided because of possible teratogenesis; nevertheless they may be considered during the second and third trimester [75].

Voriconazole and posaconazole are wide spectrum antifungal azoles that have been suggested in the treatment of disseminated coccidioidomycosis to skin and cases that are refractory to treatment including cutaneous cases, but the studies are limited [76–79].

InterferonƔ has also shown success as an adjuvant treatment in two cases of disseminated coccidioidomycosis refractory to amphotericine B or itraconazole [80].

Conclusions

The skin and subcutaneous tissue is the most extensive and accessible organ in the body; it is a place where it interacts in situ with Coccidoides spp. and eventually the responses reflect both in the diverse clinical and serological manifestations. The infection progresses until control, latency, cure with complete elimination of the fungus or until dissemination and death.

The diagnosis of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis is relatively easy when revising the history and physical examination, and the recognition of the clinical characteristics and analysis of specific tests of the patient. Where difficulty arises is having the diagnostic certainty between a case of primary cutaneous cases and secondary dissemination to skin from a pulmonary focus. (Table 1).

It is necessary to stress that in order to make a correct diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis; one must think of this disease, especially in patients that live or have ever lived in endemic zones. However, new autochthonous cases can be observed in the perimeter of the areas that are historically considered as endemic, in other suspicious zones or in others that are not recognized as susceptible to the disease.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Colombo AL, Tobón A, Restrepo A, et al. Epidemiology of endemic systemic fungal infections in Latin America. Med Mycol. 2011;49(8):785–98.

Benedict K, Thompson III GR, Deresinski S, Chiller T. Mycotic infections acquired outside areas of known endemicity. United States Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(11):1935–41. doi:10.3201/eid2111.141950.

Blair J, Chang YH, Cheng MR, et al. Characteristics of patients with mild to moderate primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(6):983–90. doi:10.3201/eid2006.131842. Prospective study and detail description of patients with pulmonary coccidioidomycosis.

Chang A, Tung RC, McGillis TS, et al. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5):944–9.

Blair JE. State-of-the-art treatment of coccidioidomycosis skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2007;1111:411–21.

Sondermeyer G, Lee L, Gilliss D, et al. Associated-associated hospitalizations, California, USA, 2000–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(10):1590–7. doi:10.3201/eid1910.130427.

CDC. Increase in reported coccidioidomycosis—United States, 1998–2011. MMWR. 2013;62(12):217–21. Epidemiology report of coccidiodomycosis cases have increased dramatically in endemic areas.

Seitz AE, Prevots DR, Holland SM. Hospitalizations associated with disseminated coccidioidomycosis, Arizona and California, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(9):1476–9. doi:10.3201/eid1809.120151.

Crum NF, Ballon-Landa G. Coccidioidomycosis in pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med. 2006;119(11):993. e11-7.

Marsden-Haug N, Goldoft M, Ralston C, et al. Coccidioidomycosis acquired in Washington State. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(6):847–50. doi:10.1093/cid/cis1028.

Litvintseva AP, Marsden-Haug N, Hurst S, et al. Valley fever: Finding new places for an old disease: Coccidioides immitis found in Washington state soil associated with recent human infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(1):e1–3. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu681. This study demonstrates colonization of soils by C. immitis linked to human infections and located outside the endemic range.

Wilson JW. The importance of portal of entry in certain microbial infections. The primary cutaneous “chancriform syndrome”. Dis Chest; 54(S1): 299–304. http://journal.publications.chestnet.org.

Deus Filho A, Deus ACB, Meneses AO, et al. Skin and mucous membrane manifestations of coccidioidomycosis: a study of thirty cases in the Brazilian states of Piauí and Maranhão. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85(1):45–51. doi:10.1590/S0365-05962010000100006.

Simental-Lara F, Bonifaz A. Coccidioidomicosis en la región lagunera de Coahuila, México. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2011;55(3):140–51.

Moreno-Coutiño G, Arce-Ramírez M, Medina A, et al. Coccidioidomicosis cutánea. Comunicación de seis casos mexicanos. Rev Chilena Infectol. 2015;32(3):339–43. This article is one of first reports of Coccidioides posadasii infection in cutaneous coccidioidomycosis.

Salas-Alanis JC, Ocampo-Candiani J, Cepeda-Valdes R, et al. Cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: Incidental finding. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2012;3:147. doi:10.4172/2155-9554.1000147.

Narang V, Garg B, Sood N, Goraya SK. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: first imported case in north India. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:422.

Kantarcioglu AS, Sandoval-Denis M, Aygun G, et al. First imported coccidiodomycosis in Turkey: a potential health risk for laboratory workers outside endemic areas. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2014;3:20–5. doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2014.01.002.

Al-Daraji WI, Al-Mahmoud RM, Ali MA. Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis: a case report from the United Kingdom. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2:494–7. www.ijcep.com/IJCEP803007.

Tortorano AM, Carminati G, Tosoni A, et al. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis in an Italian nun working in South America and review of published literature. Mycopathologia. 2015;180(3-4):229–35. doi:10.1007/s11046-015-9895-0.

Whiston E, Taylor JW. Comparative phylogenomics of pathogenic and nonpathogenic species. G3: Genes Genomes Genetics. 2016;6(2):235–44. doi:10.1534/g3.115.022806. Phylogenetic study on Coccidioides spp. gene family expansion/contraction and their metabolism.

Nguyen C, Barker BM, Hoover S, et al. Recent advances in our understanding of the environmental, epidemiological, immunological, and clinical dimensions of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(3):505–25. doi:10.1128/CMR.00005-13. This is a complete review of the disease.

Gaidici A, Saubolle MA. Transmission of coccidioidomycosis to a human via a cat bite. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(2):505–6. doi:10.1128/JCM.0186008.

Johnson L, Gaab EM, Sanchez J, et al. Valley fever: danger lurking in a dust cloud. Microbes Infect. 2014;16(8):591–600. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2014.06.011. This is a review comprehending pathogenic aspects and host immune response.

Lewis ERG, Bowers JR, Barker BM. Dust devil: the life and times of the fungus that causes valley fever. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(5):e1004762. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004762.

Vinh DC, Schwartz B, Hsu AP, et al. Interleukin-12 receptor b1 deficiency predisposing to disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):e99–102.

Hung C-Y, Seshan K, Yu J, et al. A metalloproteinase of Coccidioides posadasii contributes to evasion of host detection. Infect Immune. 2005;73(10):6689–703.

Fanning S, Mitchell AP. Fungal biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(4):e1002585. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002585.

Sharpton TJ, Stajich JE, Rounsley SD, et al. Comparative genomic analyses of the human fungal pathogens Coccidioides and their relatives. Genome Res. 2009;19:1722–31.

Li J, Yu L, Tian Y, Zhang KQ. Molecular evolution of the deuterolysin (M35) family genes in Coccidioides. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31536. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031536.

Mirbod-Donovan F, Schaller R, Hung C-Y, et al. Urease produced by Coccidioides posadasii contributes to the virulence of this respiratory pathogen. Infect Immun. 2006;74(1):504–15. doi:10.1128/IAI.74.1.504-515.2006.

Wise HZ, Hung C-Y, Whiston E, Taylor JW, Cole GT. Extracellular ammonia at sites of pulmonary infection with Coccidioides posadasii contributes to severity of the respiratory disease. Microb Pathog. 2013;0:19–28. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2013.04.003.

Ondo AL, Zlotoff J, Mings SM, et al. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: an incidental finding. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(3):e42–3.

DiCaudo DJ. Coccidioidomycosis: a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(6):929–42.

DiCaudo DJ. Coccidioidomycosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33:140–5.

Garcia-Garcia SC, Salas-Alanis JC, Gomez-Flores M, et al. Coccidioidomycosis and the skin: a comprehensive review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(5):610–21. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153805.

Mangold AR, DiCaudo DJ, Blair JE, Sekulic A. Chronic interstitial granulomatous dermatitis in coccidioidomycosis. Br J Dermatol. 2015; 17. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14295

Garza-Chapa JI, Martínez-Cabriales SA, Ocampo-Garza J, et al. Cold subcutaneous abscesses as the first manifestation of disseminated coccidioidomycosis in an immunocompromised host. Australas J Dermatol. 2015. doi:10.1111/ajd.12424.

Langelier C, Baxi SM, Iribarne D, Chin-Hong P. Beyond the superficial: Coccidioides immitis fungaemia in a man with fever, fatigue and skin nodules: a case of an emerging and evolving pathogen. BMJ Case Reports. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-205333.

Carpenter JB, Feldman JS, Leyva WH, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(5):831–7.

Ocampo-Garza J, Castrejón-Pérez AD, Gonzalez-Saldivar G, et al. Cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: a great mimicker. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211680.

Rodriguez R, Konia T. Coccidioidomycosis of the tongue. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129(1):e4–6.

Ellerbrook L, Laks S, Cocciodioidomycosis osteomyelitis of the knee in a 23-year-old diabetic patient. Radiol Case Reports. (Online) 2014; 10(1); 1034.

Jaramillo-Moreno G, Velázquez-Arenas L, Mendez-Olvera N, Ocampo-Candiani J. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:121–3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02446.x.

Rojas-García OC, Moreno-Treviño MG, González-Salazar F, et al. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis in an infant. Gac Med Mex. 2014;150(2):175–6.

Saúl A, Bonifaz A. Clasificación de la esporotricosis. Una propuesta con base en el comportamiento inmunológico. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2011;55(4):200–8.

Tchernev G, Cardoso JC, Chokoeva AA, et al. The “mystery” of cutaneous sarcoidosis: facts and controversies. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2014;27(3):321–30.

Newlon HR, Lambiase MC. Disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis masquerading as lupus pernio. Cutis. 2010;86(1):25–8.

Crum NF. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis with cutaneous lesions clinically mimicking mycosis fungoides. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(11):958–60.

Arora NP, Taneja V, Reyes Sacin C, et al. Coccidioidomycosis masquerading as malignancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2012. doi:10.1136/bcr.12.2011.5357.

Wilson JW, Smith CE, Plunkett OA. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. The criteria for diagnosis and a report of a Case. Calif Med. 1953;79(3):233–9. PMCID: PMC1521839.

Pappagianis D. The phenomenon of locus minoris resistentiae in coccidioidomycosis. In: Coccidioidomycosis, Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Coccidioidomycosis, San Diego, Calif. March, 14-17, 1984. Washington, DC: The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases; 1985:319–329.

Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV, Ruocco E. The immunocompromised district: a unifying concept for lymphoedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(12):1364–73. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03345.x.

Ruocco V, Ruocco E, Piccolo V, et al. The immunocompromised district in dermatology: a unifying pathogenic view of the regional immune dysregulation. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(5):569–76. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.04.004.

Muñoz-Hernández B, Palma-Cortés G, Carlos Cabello-Gutiérrez C, et al. Parasitic polymorphism of Coccidioides spp. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:213. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/213 . In this study, the authors observed parasitic morphological diversity of Coccidioides in clinical samples.

Kappel ST, Wu JJ, Hillman JD, et al. Histopathologic findings of disseminated coccidioidomycosis with hyphae. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(4):548–9. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.4.548.

Ampel NM. The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. F1000 Med Rep. 2010;2:2. doi:10.3410/M2-2.

Berg N, Ryscavage P, Kulesza P. The utility of fine needle aspiration for diagnosis of extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis: a case report and discussion. Clin Med Res. 2011;9(3-4):130–3.

Aly FZ, Millis R, Sobonya R, et al. Cytologic diagnosis of coccidiodomycosis: spectrum of findings in Southern Arizona patients over a 10 year period. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016;44(3):195–200. doi:10.1002/dc.23419.

Khalbuss WE, Michelow P, Benedict C, et al. Cytomorphology of unusual infectious entities in the Pap test. Cyto J. 2012;9:15. doi:10.4103/1742-6413.97763.

Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(2):247–80. doi:10.1128/CMR.00053-10.

Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M, Arenas-Guzman R. Morphological findings of deep cutaneous fungal infections. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36(7):531–56.

Jehangir W, Tadepalli GS, Sen S, et al. Coccidioidomycosis and blastomycosis: endemic mycotic co-infections in the HIV patient. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7(3):196–8. doi:10.14740/jocmr2036w.

Miller JM, Astles R, Baszler T, et al. Guidelines for safe work practices in human and animal medical diagnostic laboratories. Recommendations of a CDC-convened, Biosafety Blue Ribbon Panel. MMWR. 2012;61(1):1–102.

Johnson R, Kernerman SM, Sawtelle BG, et al. Reformulated spherule-derived coccidioidin (Spherusol) to detect delayed-type hypersensitivity in coccidioidomycosis. Mycopathologia. 2012;174(5-6):353–8. doi:10.1007/s11046-012-9555-6.

Wack EE, Ampel NM, Sunenshine RH, Galgiani JN. The return of delayed-type hypersensitivity skin testing for coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(5):787–91. doi:10.1093/cid/civ388.

Mendoza N, Blair JE. The utility of diagnostic testing for active coccidioidomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(4):1034–9. doi:10.1111/ajt.12144.

Arvanitis M, Anagnostou T, Fuchs BB, et al. Molecular and nonmolecular diagnostic methods for invasive fungal infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(3):490–526. doi:10.1128/CMR.00091-13.

Navalkar KA, Johnston SA, Woodbury N, et al. Application of immunosignatures for diagnosis of valley fever. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21(8):1169–77. doi:10.1128/CVI.00228-14. This is a new technology improve Coccidioidomycosis diagnosis with a higher sensitivity and it can distinguish related infections.

Duarte-Escalante E, Frias-De leon MG, et al. Molecular markers in the epidemiology and diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2014;31(1):49–53.

Binnicker MJ, Buckwalter SP, Eisberner JJ, et al. Detection of Coccidioides species in clinical specimens by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(1):173–8. doi:10.1128/JCM.01776-06.

Mitchell M, Dizon D, Libke R, et al. Development of a real-time PCR assay for identification of Coccidioides immitis by use of the BD Max system. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(3):926–9. doi:10.1128/JCM.02731-14.

Ampel NM. The treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2015;57(S19):51–6. doi:10.1590/S0036-46652015000700010.

Welsh O, Vera-Cabrera L, et al. Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30(6):573–91.

Bercovitch RS, Catanzaro A, Schwartz BS, et al. Coccidioidomycosis during pregnancy: a review and recommendations for management. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(4):363–8. doi:10.1093/cid/cir410.

Catanzaro A, Cloud GA, Stevens DA, et al. Safety, tolerance, and efficacy of posaconazole therapy in patients with nonmeningeal disseminated or chronic pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(5):562–8.

Chang M, Chagan L. Posaconazole (Noxafil), an extended-spectrum oral triazole antifungal agent. Pharm Ther. 2008;33(7):391–426. PMC2740948.

Lat A, Thompson III GR. Update on the optimal use of voriconazole for invasive fungal infections. Infect Drug Resist. 2011;4:43–53. doi:10.2147/IDR.S12714.

Kim MM, Vikram HR, Kusne S, et al. Treatment of refractory coccidioidomycosis with voriconazole or posaconazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(11):1060–6. doi:10.1093/cid/cir642.

Duplessis CA, Tilley D, Bavaro M, et al. Two cases illustrating successful adjunctive interferon-g immunotherapy in refractory disseminated coccidioidomycosis. J Infect. 2011;63(3):223–8. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2011.07.006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Martin Arce and Daniela Gutierrez-Mendoza declare that we have no conflicts of interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Fungal Infections of Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arce, M., Gutierrez-Mendoza, D. Primary and Disseminated Cutaneous Coccidioidomycosis: Clinical Aspects and Diagnosis. Curr Fungal Infect Rep 10, 132–139 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-016-0263-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-016-0263-4