Abstract

Psychological folklore and empirical evidence suggest children of incarcerated parents are at risk for a range of adverse outcomes throughout life. While researchers and practitioners have aimed to understand and mitigate these risks, no study to date has examined how alternative sentencing affects child outcomes. The purpose of this study was to examine if maternal alternative criminal sentencing affected children’s behavior and parent–child attachment as reported by children. Children ages 8–14 whose mothers were recently released from an alternative criminal sentencing program were compared with children whose mothers had been recently released from prison. One hundred and two mothers and their children participated in this study. Results revealed statistically significant differences with children of alternatively sentenced mothers performed better on externalizing behavioral problems, total behavioral problems, parental trust, parental alienation, parental communication, and total parent–child attachment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the last 30 years, the number of imprisoned adults in the United States has increased by 500 %, and the United States continues to lead the world in the number of both incarcerated men and women (Glaze and Maruschak 2010; Harris et al. 2010). Due to various federal and state public policy initiatives requiring jail or prison sentences for nonviolent offenders, the majority of prisoners entering the criminal justice system in the United States each year are serving time for nonviolent offenses (Glaze and Maruschak 2010.) This mass incarceration of Americans generates a range of costs and consequences for society.

Children of incarcerated parents are perhaps the greatest casualties of this system. Studies indicate that a total of 2.7 million children, 1 in every 28, have a parent incarcerated in the United States and that two thirds of these children’s parents are non-violent offenders (Pew Center on the States 2010). According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the number of incarcerated parents of minor children increased by nearly 80 % between 1991 and 2007, and this number outpaced the growth of the general prison population (Glaze and Maruschak 2010). While this incarceration trend is recognized, additional research on the myriad effects of parental incarceration on children is needed. Though research seems to be on the rise, this paucity of scholarship presents an academic gap. More children are directly affected by parental incarceration than by other developmental challenges such as, for example, autism spectrum disorders (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013b). Furthermore, studies that do exist on children of incarcerated parents are largely based on reports given from the parent’s perspective, rather than both the parent’s and child’s viewpoint (Dallaire and Wilson 2010).

Even with limited research, the negative effects of parental incarceration on minor children are compelling, and the problems that each child faces are numerous (Murray and Farrington 2005; Dallaire 2007; Geller et al. 2009; Roettger and Swisher 2011; Tasca et al. 2014). Children of prisoners have been considered the unsuspecting, hidden “orphans of justice” (Shaw 1992, p. 41) when their parents commit crimes grave enough to be placed behind bars. A number of studies have considered the effects of parental incarceration on the psychological and physical well-being of children (Geller et al. 2009; Turney 2014). One thing is clear: When a parent is incarcerated, children suffer. Children of prisoners have committed no crime, but they often have to give up many things that are important to them, their well-being, and their life trajectory (Murray et al. 2012). Recent studies have suggested that compared to their peers, children of incarcerated parents are more prone to serious academic and disciplinary problems in school and to mental and physical health problems (Shlafer and Poehlmann 2010; Turney 2014). These children, who typically already come from disadvantaged environments, are faced with the reality of not seeing their parent in the same context, if at all, for many years. The societal problem, therefore, is one of at-risk children who face a higher risk of having lifelong adverse outcomes than their peers. Given this information, numerous children across the United States dealing with the emotional and developmental hardship of having a parent in prison may wind up behind bars themselves (Murray and Farrington 2005; Jimenez 2014).

The state of Oklahoma has the highest incarceration rates for women in the nation per capita and holds the number three position for incarcerated men (Carson and Golinelli 2013). According to the Oklahoma Department of Corrections (2012), Oklahoma more than doubles the national average in the rate of female offender incarcerations at 129 per 100,000 population; the nation’s average female incarceration rate is 57 per 100,000 population. Oklahoma’s title as the United States’ capital of female incarceration may have the most to do with its laws and public policies. In Oklahoma most of the women entering the department of corrections are first-time offenders. Of the over 1000 women admitted to Oklahoma’s prison system annually, nearly one in five are admitted for a technical violation of probation or parole. Drug offenses account for over half of Oklahoma’s female prison admissions, and the majority of women are assigned to minimum, medium, or community corrections security levels (Oklahoma Department of Corrections 2014; Sharp et al. 2014, p. 2).

Furthermore, while incarceration rates throughout the United States are decreasing, incarceration rates in Oklahoma remain as high or higher than in previous years (Carson and Golinelli 2013). Oklahoma ranks among the highest for offenders in prison compared with other states, which should translate to greater number of crimes committed; however, the state’s crime rates are comparable, rather than higher, to other states. Privatized prisons, which have been documented to increase inmate recidivism, also exist in the state of Oklahoma (Spivak and Sharp 2008). Due to this, more than 26,000 children in Oklahoma on any given day have a parent in prison (Sharp et al. 2010).

The damage to children and families of the incarcerated coupled with the perpetuation of the cycle of intergenerational incarceration could be categorized as the most destructive and pervasive elements of the current penal structure in the United States. In an effort to offset these elements, changes in structure have taken place in some states that allow non-violent offenders, typically substance abuse offenders, to receive rehabilitation through alternative sentencing (Pearson 2009). Oklahoma began its first nonviolent, individualized wrap-around alternative to incarceration for females in June 2009 for women facing significant prison sentences through a public-private partnership (George Kaiser Family Foundation 2013). While the positive relationship between treatment and improved offender behavior and recidivism rates has been documented, little is known about how treating parents’ problems affects the outcomes of their children (Phillips et al. 2009).

1 Purpose of Study

This study examines whether parent placement in an alternative criminal sentencing program is associated with child well-being compared to traditional sentencing. Presuming the negative outcomes of children of prisoners are attributed at least in part to their parents’ incarceration, the next logical step is to make efforts to better understand the distinct relationship between the parents’ differentiating experiences within the criminal justice system and their children’s outcomes. This study advances the literature in several ways: First, greater understanding of the latter relationship could help inform the best practices utilized by agencies that work with both non-violent offenders and the children of prisoners alike. Second, a better understanding of the effects of alternative criminal sentencing programs could determine important information about children of prisoners’ outcomes in terms of their attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors as they relate to parental incarceration. The outcomes targeted by alternative sentencing programs within the criminal justice system could be subsequently enhanced through this understanding. Though the treatment of offenders is debated, a common thread among many community stakeholders is certainly a desire for children of convicted offenders to become positive, productive, and contributing members of society. The absence of research in this area impedes scholars, practitioners, and those working in correctional and social service agencies from establishing an agreed upon best practice for non-violent parent offenders in terms of their children.

2 Alternative Criminal Sentencing

Of those entering the federal prison system in 2011 in the United States, 83 % were non-violent offenders, mostly substance abuse offenders (Carson and Sabol 2012). For most of these offenders, access to any type of therapy or rehabilitative assistance in both state and federal prisons was found to be limited (Glaze and Maruschak 2010). Research has indicated that therapeutic alternative criminal sentencing such as substance abuse treatment positively correlated with improved offender behavior and reduced recidivism (Murray et al. 2014; Wexler et al. 1999). Furthermore, according to a poll conducted by the Pew Research Center, 72 % of Americans support a criminal justice system that aims not only to punish but also to rehabilitate (2004). Alternative criminal sentencing intervention services can be administered through a variety of settings and can include probation, community service, and/or therapeutic rehabilitation. For the purposes of this study, alternative criminal sentencing can take place within the Department of Corrections in an institution other than prison that offers therapeutic modalities. It can also occur in non-governmental agencies that assist the legal system in the rehabilitative process.

Given this information, providing treatment options to non-violent offenders is a desirable practice as it benefits society independent of any positive consequence alternative criminal sentencing may or may not have on children; however, if the possibility of spillover effects on children exists, the case in favor of alternative criminal sentencing is heightened (Phillips et al. 2009, p. 121).

3 Maternal Incarceration as a Risk Factor

Maternal incarceration presents a unique risk for children. When a father goes to prison, children are more likely to stay in the care of their mother, whereas when mothers become incarcerated, children not only suffer from a disrupted attachment relationship but they also are much more likely to be transferred to the care of another individual (Dallaire 2007). Maternal incarceration has also been linked to a likelihood that children will not earn a high school diploma, and it has been found that children of incarcerated mothers are more likely than children of incarcerated fathers to be identified as suffering from mental health problems (Bussell 2014; Tasca et al. 2014). Perhaps most alarming, though, is the increased risk of incarceration for the child. In a comparative analysis of maternal incarceration and paternal incarceration, Dallaire (2007) found that regular drug use in mothers predicted incarceration of their minor children as adults. Compared with fathers, mothers in the study were 2.5 times more likely to report that their adult children were incarcerated. Additionally, the more risk factors to which children were exposed, including repeated maternal incarceration, increased children’s likelihood of adult incarceration. Other recent studies have found similar results (Jimenez 2014).

4 Effects of Alternative Sentencing on Children of Incarcerated Parents

Given the intergenerational prevalence of criminal behavior and incarceration seen above, the case for penal policies and programs that reduce recidivism is appealing. Though sentencing options may appear to be an appealing way to affect children through parental change, research is needed to support the argument parental alternative criminal sentencing positively correlates to improved child outcomes. However, little research has been directed at understanding the effects of alternative sentencing on families and children of the incarcerated. Phillips, Gleeson, and Waites-Garrett’s (2009) review asked whether parental substance abuse treatment predicts positive outcomes for children. The study found that while it is known that parental substance abuse has profound negative effects on children, existing research is limited and little is known about how alternative sentencing and treating parents’ substance abuse affects children’s outcomes.

Murray et al. 2014 book outlines studies on children of prisoners in four countries: England, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the United States. This book reviews studies representing thousands of children, and its major finding suggests that the structure and type of incarceration a parent faces is vital to determining the lifelong risk parental incarceration poses for their children. The study reported that long-term risks for children are minimized when the focus of incarceration was on offender “rehabilitation rather than retribution” such as in an alternative criminal sentencing environment (Murray et al. 2014, p. 143). Further, contexts in which punitive penal policies prevailed created a climate in which parental incarceration predicted lifelong adverse outcomes, including criminal behavior as adults, for children of prisoners.

5 Behavioral Problems in Children

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study is perhaps the largest study of its kind conducted. This longitudinal study found that exposure to specific childhood difficulties affects various outcomes in adults, including physical health problems, mental health problems, and risky behaviors such as substance use and abuse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013a, b). Having a parent in prison is recognized as an ACE that is separate and unique from other childhood experiences because of the emotional impact parental incarceration has on children (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2013a, b). Other research has shown that negative emotionality has significant links to deviant behavior (Agnew 2006). Furthermore, according to the ACE study, each additional adverse childhood experience increases the likelihood of substance abuse problems, which are linked to depression, anxiety, and other behavioral problems.

The development of behavioral problems in childhood, depending on severity, may affect a child’s ability to acquire necessary skills and may negatively affect a child’s life trajectory over the long term. The bulk of existing research suggests that parental incarceration may lead to behavioral problems in children of incarcerated parents (Murray et al. 2012). Among the behavior problems identified by these studies that children of incarcerated parents are more likely to experience are fear, aggression, anxiety, sadness, loneliness, guilt, low self-esteem, social withdrawal, attention deficit disorder, conduct problems, and depression (Dallaire and Wilson 2010; Harris et al. 2010; Murray and Farrington 2005; Roettger and Swisher 2011; Turney 2014). Behavioral problems in children of prisoners may occur as a result of strained or disrupted familial relations or as a reaction to the social stigma that often accompanies parental imprisonment (Shlafer and Poehlmann 2010).

Murray and Farrington’s (2005, 2008) longitudinal studies of 411 English boys compared boys who experienced parental incarceration before age 10 to those separated from their parent(s) for other reasons. The study found that boys affected by parental incarceration experienced double the risk for externalized behavioral problems, internalized behavioral problems, and other adverse outcomes even after accounting for family risk factors. Moreover, the boys who experienced parental incarceration were at nearly five times the risk of becoming incarcerated as an adult than the boys who were not separated from their parents and faced three times the risk of imprisonment than the boys who were separated from a parent for other reasons. Even though the findings regarding the risk factors of boys of incarcerated parents showed significant predictive differences, the study’s sample size of children of prisoners was small. Also, the study did not take into account whether other risk exposures happened before or after the parents’ incarceration (Kinner et al. 2007). Murray and Farrington (2008) showed a relationship between parental incarceration and negative emotional and behavioral outcomes in children. In Murray, Farrington, and Sekol’s (2012) meta-analysis of 40 empirically based studies on children of incarcerated parents, children’s externalized behavioral problems was the only outcome associated with parental incarceration after controlling for parental criminality and children’s outcomes before parental incarceration.

Hser, Evans, Li, Metchik-Gaddis, and Messina’s 2014 study examined children of substance abusing mothers 10 years after the mothers had been admitted to drug abuse treatment centers. All children in that study had been exposed to drugs, and the study identified characteristics in the mothers that may have placed their children at risk for behavioral problems. Behavioral problems in children were related to mother ethnicity, the severity of problems in family and social relationships, and mother mental health. The authors asserted “assisting mothers in their family/social relationship and treating psychological problems may have an added value to prevent or reduce behavioral problems of their children” (p. 1).

Other studies, however, have suggested that parental incarceration is not a significant factor for child behavior (Kinner et al. 2007; Phillips and Erkanli 2008). For example, Phillips and Erkanli’s study of maltreated children who were subjects of reports to Child Protective Services found no significant difference in emotional functioning of children whose mothers had been arrested and those whose mothers had not been arrested, though this study specifically assessed arrest histories of mothers and not incarcerations.

The mixed findings referenced in the previous paragraphs suggest that other factors may play a role in how incarceration affects child behavior. Nonetheless, overall, the literature suggested that parental incarceration might be predictive of behavioral problems in children of those imprisoned. This trend leads to the first hypothesis of this study. Does parental alternative sentencing mitigate these negative behavioral problems in children of prisoners? This study hypothesizes that children whose mothers received alternative criminal sentencing will have fewer behavioral problems than children whose mothers were incarcerated.

6 Parent–Child Attachment

A significant concern of practitioners and researchers alike for children of incarcerated parents is parent–child attachment (Poehlmann 2005). When a parent who is the primary caregiver goes to prison, a child loses physical contact with his or her attachment figure. Relatively few empirically based studies have investigated the impact of parental incarceration on children’s parent–child attachment, and no studies were found that explored how parental alternative criminal sentencing specifically affects attachment relationships in children.

Attachment theory draws from developmental psychology and behavioral biology. It provides an explanation of how the parent–child relationship emerges and influences subsequent child development (Bowlby 1969). Bowlby argued that attachment is related to the attitudes and behaviors that children develop toward their attachment figures, in most instances their parents. Later development in terms of sense of self and future relationships can be defined by childhood attachment. A vast amount of research confirms the importance of the biologically based reciprocal relationship between an infant or child and the child’s parent (Bowlby 1980), though the quality of the parent–child relationship will ultimately determine the security of the child’s attachment. Research suggests that attachment security predicts social competence and problem solving (Sroufe et al. 1993). Bowlby (1980) further explained that the establishment of this security for the infant and the development by the infant/child of internal working models is crucial. It is also known that separation from attachment figures poses a threat to child development and causes emotional distress (Bowlby 1980).

Maintaining proximity to an attachment figure in order to safeguard children from potential threats serves as a main function of the child’s attachment system (Bowlby 1980; Shlafer and Poehlmann 2010). Research suggests that children of incarcerated parents suffer when separated from their mothers or fathers and that major developmental milestones involving parent–child relations are put at risk (Poehlmann 2005; Shlafer and Poehlmann 2010). Separation due to parental incarceration may be as difficult as other forms of parental loss but is exacerbated by a stigma associated with incarceration as well as shame, secrecy, lack of familial support, and/or lack of societal compassion that may exist when a parent is incarcerated (Phillips and Gates 2011). Using a mixed-method, longitudinal approach, one study found children of incarcerated mothers experienced high rates of attachment insecurity and scored lower on tests of intelligence (Shlafer and Poehlmann 2010). Poehlmann (2005) found that 37 % of children of prisoners had the benefit of secure attachments versus 70 % of children in general population.

Lack of contact with an incarcerated parent specifically has been shown to be associated with child feelings of parental alienation (Shlafer and Poehlmann 2010). A comprehensive review of research related to attachment and children of prisoners conducted by Poehlmann et al. (2010) found that 82 % of studies showed that contact with children benefits prisoners, while 58 % of studies found prisoner-child contact benefits for children. These benefits for children included, but were not limited to, more secure parent–child attachments, reduction in depression and somatic complaints, increased self-esteem, fewer school dropouts and suspensions, and fewer feelings of parental alienation. An important body of research, therefore, has supported the notion that fostering relationships between incarcerated parents and their children is generally mutually beneficial (Poehlmann et al. 2010). Poehlmann et al. (2010) also stated that interventions should exist at each contextual level, and the authors contended that improving macrosystems for children and parents, including sentencing policies, might improve parent–child contact.

With the previously presented research findings in mind, it follows that alternative criminal sentencing programs might offer added security for children of prisoners. Children may be more likely to know their parents’ whereabouts and, thus, feel less anxiety and less detached from parents. Many alternative sentencing and jail diversion programs offer a parenting component and work to reunite children with their parents after treatment is completed. This parenting component could help to increase parent–child attachment after treatment completion. Additionally, alternative criminal sentencing programs may be more likely to offer safe and developmentally appropriate visitation for children than currently exist in traditional in-prison incarceration (L. Garrison, personal communication, January 12, 2013). Taken together, these components of various alternative criminal sentencing programs may lead to increased attachment security for children of prisoners, a situation that leads to the second hypothesis of this study: Children whose mothers received alternative criminal sentencing will have higher levels of parent–child attachment than children whose mothers were incarcerated.

7 Method

7.1 Participants

This study took place in an urban community located in the southern plains of the United States. Indeed, this location is characterized as having among the highest per capita incarceration rates for both sexes with an estimated high percentage of children of prisoners (Sharp et al. 2010). This study’s researchers selected two charitable, non-profit agencies serving this population to recruit participants. One agency serves children of recently incarcerated parents; the other serves women receiving alternative sentencing for nonviolent crimes.

The first agency is an independent local non-profit agency focused on ending generational incarceration through a variety of prevention services to children of prisoners ages five through eighteen. Its mission is to end generational incarceration one child at a time, and its main service areas include community and school-based after school programs, weekend retreats, summer camps, family gatherings, and case management services. Because of high local criminal recidivism rates, the agency continues to serve its clients after their parents have been released from the criminal justice system. Clients ages 8–14 whose mothers have been released from prison within the past 48 months and their care giving parent were included in the study. To ensure homogeneous sampling, mothers convicted of non-violent offenses were included in the study.

The second agency is a local public-private partnership offering a non-incarceration alternative sentencing for women convicted of nonviolent criminal offenses who face significant prison sentences. Its mission is to reduce the number of women sent to prison from Tulsa County for nonviolent drug-related offenses through an intensive outpatient program. In order to be potentially eligible for the program, a woman must be over 18 years old, involved with the criminal justice system, and ineligible for other DOC diversion programs or courts. A woman must also have a history or risk of substance use and abuse and be at imminent risk of incarceration. Women with children are given priority for program admission (George Kaiser Family Foundation 2013). Women meeting the above eligibility requirements are admitted to the program through a judge’s order. Judges base their decisions on a number of factors including the recommendations of the agency, recommendations of the District Attorney, nature of crime(s) committed, criminal history, and prior attendance in court. Most women enter the program through a “blind plea” where the judge maintains control of the case while a woman is in the program, and he or she is able to make sentencing decisions on the case as he or she sees fit (Women in Recovery, personal communication, 2014).

Addiction, abuse, and poverty are factors that impact the vast majority of this alternative sentencing program’s participants. The agency’s services range from therapy and treatment to housing, educational, and life skills training. Their goal is to help women conquer their drug addiction, recover from trauma and acquire the essential economic, emotional, and social tools to build successful and productive lives. The program also offers parent skill training and family reunification services (Family Children’s Services 2013). Women participating in the program individually phase through the three stages of the program. Each stage offers participants greater independence and responsibility. In stage one and two, children are permitted to visit mothers, and parent–child interaction therapy is employed. Women in the final stage of the program, stage three, have transitioned to an independent living situation and have regained custody or visitation of their children. Stage three participants and their children ages 8–14 and graduates who have completed the agency’s program within the last 48 months and their children ages 8–14 were included in the study.

All mothers in this study had custody of or weekly residential visitation with their children. 85 % of the children whose mothers were recently released from prison lived with their mother prior to her most recent incarceration. Two mothers did not answer this survey question, and one child was born in prison. 81 % of the children whose mothers received alternative criminal sentencing lived with their mother prior to her most recent involvement with the Department of Corrections, and one mother did not answer this question.

During their mothers’ sentencing, all children in this study were in familial custodial placements. Primary caregiver relationships to children included grandmother, father, grandfather, aunt or uncle, great grandmother, older sibling, cousin, and godparent. Alternatively sentenced mothers served their sentences within an hour of their home, and through their alternative sentencing, visitation with their children was coordinated with children’s caregivers. All recently incarcerated mothers served their sentence within the state of Oklahoma and were therefore a maximum of 3 h from their children. Prison visitation is permitted for non-violent offenders in the state of Oklahoma though no private or public agency in the state of Oklahoma monitors which offenders are parents and transportation is often an issue for families (Sharp et al. 2010),

As seen in Table 1, participating mothers who were recently incarcerated ranged in age from 27 to 55 years (M = 38.47, SD = 7.36), and their children ranged in age from 8 to 14 years old (M = 11.75, SD = 2.25). This group of child participants consisted of 9 boys (45 %) and 11 girls (55 %). Participating mothers who received alternative criminal sentencing ranged in age from 28 to 48 years old (M = 34.03, SD = 5.64), and their children ranged in age from 8 to 14 (M = 11.04, SD = 1.99). This group of child participants consisted of 17 boys (59 %) and 12 girls (41 %). Mothers who were recently incarcerated identified themselves as follows: Caucasian (35 %), African American (25 %), Native American (20 %), and Hispanic (10 %). One mother (5 %) identified herself as having multiple ethnicities. Children of these mothers identified themselves as follows: Caucasian (35 %), African American (20 %), Native American (15 %), and Hispanic (5 %). Five children of recently incarcerated mothers (25 %) identified themselves as having multiple ethnicities. Mothers who received alternative criminal sentencing identified themselves as follows: Caucasian (88 %) and Native American (12 %). Children of these mothers identified themselves as Caucasian (59 %), Native American (10 %), African American (7 %), and Hispanic (3 %). Six children of mothers who received alternative criminal sentencing (21 %) identified themselves as having multiple ethnicities.

Education of recently incarcerated mothers ranged from less than 12th grade (40 %), to high school completion or equivalency (20 %), to some post-secondary education (25 %), and finally college or technical school completion (15 %). With the education component of the participating alternative sentencing program, it is not surprising that mothers who received alternative criminal sentencing had a higher high school equivalency completion. These education levels ranged from less than 12th grade (18 %), high school equivalency (36 %), some post secondary education (24 %), and completion of a college or technical degree (18 %). Many mothers had experienced multiple incarcerations (62 %) with a mean incarceration number of 3.72 (SD = 4.18) for mothers who received alternative criminal sentencing and 2.58 (SD = 1.39) for mothers who had recently been released from prison. The most recent controlling offense for all mothers in this study was non-violent in nature.

7.2 Procedures

The study protocol was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board following full board review. Permission from participating agencies to access participants was obtained and efforts were put in place to ensure ethical treatment of and minimize risks to all participants. Several informational sessions were held at both participating agencies to recruit potential maternal participants. In these sessions, the researchers outlined study procedures and invited mothers to participate in the research. Mothers who were not the child’s legal guardian or did not possess regular visitation of the child were excluded from the study. Eligible adults with children ages 8–14 were provided with informed consent forms. Eligible mothers who agreed to participate in the research completed informed consent documents for themselves and their children as well as the study questionnaire and a child contact form. Upon completion, adult participants returned all study documents to the researcher at the program site. The researcher then contacted child participants via phone. Phone conversations with children were audio recorded, and child assent was obtained via phone. Both mother and child participants received sandwich coupons from a large fast food organization as compensation for their time.

7.3 Measures

Child Behavior

The Child Behavior Check List (CBCL) is a rating scale derived from clinical and research literature that consists of 118 Likert-type items related to child behavior problems (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). The 3-point rating scale ranges from “not true” to “very true or often true” of the child. The scale also contains 20 social competency items that assess school functioning, social interactions, and the frequency and quality of children’s various activities and interactions. The CBCL consists of three sections: Competence and Adaptive, Empirically Based, and DSM-Oriented. The Competence & Adaptive and Empirically Based sections of the CBCL were used in this study and sum and mean scores for each section were calculated. The four main variables studied through the CBCL in the current study were converted from a raw score into a normalized T score. These scores are based on percentiles up to a T score of 70 (98th percentile). As a whole, the psychometric properties of the CBCL have been tested in a comprehensive and academic manner with numerous studies supporting the instrument’s score validity and reliability.

CBCL: Competence & Adaptive Scales

The first section of the CBCL assesses a child’s “functional strengths at home and school, with peers, and in recreational activities” (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001, p. 49). Achenbach and Edelbrock proposed four subscales for the items with reliability alphas between 0.63 and 0.79. Only the Total Competence scale, was computed in the current study, for which a reliability alpha of 0.79. was reported.

CBCL: Empirically Based Scales

The CBCL Empirically Based Scales (or Syndrome Scales) assess syndromes, or sets of problems, that tend to co-occur that school-aged children may possess (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). Only the Internalizing Aggressive Behavior Subscale, Externalizing Aggressive Behavior Subscale, and the Total Problems Scale were computed in the current study. Both Internalizing Aggressive Behavior (.90) and Subscale Externalizing Aggressive Behavior (.94) present adequate score internal consistency reliability.

7.4 Child Attachment

In this study, researchers used the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment Revised (IPPA-R; Gullone and Robinson 2005) to assess child attachment. The IPPA-R is a revised version of IPPA developed for children and young adolescents in order to assess their perceptions of the positive and negative affective or cognitive dimensions of their relationships with parents and close friends. All items were rated on a three-point Likert-type scale ranging from “always true” to “never true.” Negatively-worded items were reverse coded.

Numerous studies have used the IPPA to explore parent–child attachment in children (Gullone and Robinson 2005; Shlafer and Poehlmann 2010). Three aspects of attachment are assessed in the IPPA-R: trust, communication, and alienation. These three areas serve as the three subscales of the IPPA-R. The Trust scale measures mutual understanding and respect in an attachment relationship. The Communication scale measures the quality, amount, and scope of spoken communication between parent and child; and the Alienation scale measures levels of the child’s anger and feelings of inter-personal isolation and separation (Gullone and Robinson 2005). For the Parent Attachment scale, Gullone and Robinson (2005) reported high internal consistency with reliability alphas ranging between 0.76 and 0.83 for children and 0.79 to 0.85 for adolescents with Trust (0.83, 0.85) demonstrating the highest internal consistency of all of the variables. Additionally, several other studies reported high internal consistency using IPPA to explore parental attachment (see Shlafer and Poehlmann 2010).

7.5 Design and Analysis

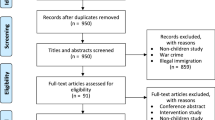

Causal-comparative research seeks to determine the reasons for an existing condition. It investigates whether differences in groups of participants are possibly based on, or tentatively caused by, one or more preexisting conditions. A cross-sectional survey design was utilized in this study. Data were obtained on two groups: children whose mothers were recently incarcerated and children whose mothers were recent graduates of an alternative sentencing program. These groups were compared for significant differences across dependent variables: total competence, externalizing behavioral problems, internalizing behavioral problems, total behavioral problems, parental trust, parental communication, parent alienation, and total parent–child attachment. Data were reported as a mean score for each group, and an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was computed for each dependent variable to determine whether the means for the two groups were significantly different from one another. An examination level of 0.05 alpha was chosen to test the null hypothesis. To further analyze the extent of the difference in the two groups’ mean scores, effect size estimates were calculated using Cohen’s d statistic.

8 Results

8.1 Child Behavior

One-way ANOVAs were conducted to see if the mean CBCL T-scores for child competence, child externalizing behavioral problems, child internalizing behavioral problem, and child total behavioral problems differed based on maternal sentencing within the criminal justice system. From Table 2, we see that the one-way ANOVAs for child externalizing behavioral problems (F (1,51) = 7.86, p = .007) and child total problems (F (1,51) = 8.80, p = .005) are statistically significant. The use of Cohen’s d effect size measure lead to the following conclusion: There is a moderate effect size for the influence of parental sentencing on both child externalizing behavioral problems (−0.74) and total behavioral problems (−0.78). This finding suggests that maternal alternative criminal sentencing corresponds to fewer behavioral problems in children of incarcerated parents.

8.2 Child Attachment

The construct of attachment was measured using IPPA scores for trust, communication, alienation, and total parent–child attachment. One-way ANOVAs were conducted to see if mean scores differed based on maternal sentencing within the criminal justice system. From Table 3, we see that the one-way ANOVAs for the three subscales of trust (F (1,46) = 26.55, p = .000), communication (F (1,47) = 17.37, p = .000), and alienation (F (1,46) = 20.80, p = .000) as well as the total scale (F (1,46) = 33.55, p = .000) are statistically significant. Cohen’s d effect size measure led to the conclusion that there is a large effect size for the influence of parental sentencing on trust (−1.32), communication (−1.06), alienation (−1.13), and total parent child attachment (−1.31). These results provide evidence to support the conclusion that maternal alternative criminal sentencing corresponds to a more secure attachment relationship for children of incarcerated parents.

9 Discussion

Parental incarceration may cause many difficulties and negatively impact long-term outcomes for children of incarcerated parents, especially for children of incarcerated mothers. The primary goal of this study was to examine and understand the impact of maternal alternative criminal sentencing on school-aged children’s behavior and parent–child attachment.

9.1 Child Behavior: Impact of Maternal Sentencing

Maternal sentencing was shown to impact child behavior as expected. With previous research suggesting that externalizing behavioral problems is the outcome that most affects children of prisoners, it is not surprising that externalizing behavioral problems in children whose mothers were incarcerated were more pronounced than in children whose mothers received alternative criminal sentencing. The total behavioral problems scale also produced a statistically significant difference in means indicating that behavior in children may be impacted by their mothers’ sentence. Though values for child internalizing behavioral problems and child competence did not produce statistically significant differences, differences between the two groups of children studied were found in the expected direction.

A possible explanation for the difference in mean scores between the two groups of children is the improvement of their mother’s parenting skills as a result of alternative criminal sentencing. On the other hand, it may be the case that children of incarcerated parents already possessed behavioral problems prior to their mothers’ arrest and sentencing, and this propensity for behavioral problems could be the result of social modeling. If children grow up seeing their parents respond negatively to stressful situations, they may be socialized to develop negative reactions to stressful life events, including parental incarceration or the stigma associated with parental incarceration (Murray et al. 2014). In an alternative criminal sentencing setting, mothers may have learned to better cope with trauma and stress, and these behaviors may have been passed down to children through social modeling. Mothers who were alternatively sentenced may also face less stress and fewer barriers to successful reintegration into society.

Explanations other than alternative sentencing for study findings in terms of child behavior also exist. Many unmeasured confounding variables may have affected study outcomes. For example, the first of these is parental criminality. While all participating mothers were most recently sentenced for a crime that was nonviolent in nature and total number of convictions are noted in this study, specific charges were not obtained; and it is unknown whether previous criminal charges were violent or nonviolent. However, researchers did measure the total number of convictions of all mothers in this study with the mothers in alternative treatment having more self-reported criminal convictions than recently released mothers. Second, preexisting genetic and social influences on child behavior were unknown and not controlled for in this study. Finally, one of many pathways to crime and incarceration for female offenders is a history of trauma and violence. In one study of women incarcerated in the state of Oklahoma, 66.4 % of women reported physical and/or sexual abuse as a child (Sharp et al. 2010). Abuse histories of mothers were not considered in this study, and controlling for maternal abuse histories might have impacted findings.

Overall this study’s findings suggest that compared with traditional sentencing, maternal alternative criminal sentencing may positively impact child behavior. Further research on the behavioral outcomes of children of alternatively sentenced mothers is needed to better understand explanatory mechanisms linking alternative criminal sentencing to improved behavioral outcomes for children of prisoners.

9.2 Parent–Child Attachment Security: Impact of Maternal Sentencing

No published studies were found that compared parent–child attachment in children of alternatively sentenced mothers and children of incarcerated mothers, though previous research on attachment security in children of prisoners has yielded varying results. The hypothesis that children whose mothers received alternative criminal sentencing would have higher levels of parent–child attachment was met by all scales examining this variable: parent trust, parent communication, parent alienation, and total parent–child attachment. While these results may be accurate, it could also be that the large effect size and significance level may have been influenced by the design of the study. Children were accessed by phone and given scales verbally. Scales given verbally may yield different results from those given by hardcopy survey. Furthermore, the nature of the work the two participating agencies do, one providing positive interventions but ultimately sentencing of mothers and the other providing support programs for children, may have consciously or unconsciously impacted children’s answers. In addition, as mentioned previously, findings could have been impacted by variables not accounted for within this study including type and severity parental criminality, parent–child attachment prior to arrest and sentencing, environmental variables, abuse histories of mothers, and prior and current mental health conditions of mothers. Finally, a more complex model may have revealed different results.

Even given these issues, the means for all variables produced significant results that should be considered. These results suggest that the alternative criminal sentencing environment allows for parent–child attachment relationships to remain more intact than traditional sentencing. These results suggest that alternative sentencing may serve as a protective factor for at-risk children of offenders. In the case of the alternative sentencing program utilized in this study, mothers’ participation in various forms of education such as parenting classes, trauma-informed therapy, vocational training, and wellness and stress education coupled with children’s increased awareness of their mothers’ physical locations and the program’s encouragement of visitation and parent–child contact could have played a critical role in helping to maintain the attachment relationship. Also of note is the fact that most felons who spend time in prison have a history with the department of corrections, and the mothers in this study who were alternatively sentenced were no exception (Glaze and Herberman 2013). With a mean reported conviction number of 3.72, the mothers who were alternatively sentenced had on average slightly (1.14) more convictions than the mothers who were recently released from prison. Given this information, it is a reasonable assumption that many children in this study had already experienced the trauma of arrest and incarceration with their mothers and may have already experienced disrupted attachment. It may be the case, then, that alternative criminal sentencing not only helps to maintain parent–child attachment relationships already present prior to arrest and conviction, but also that it helps to repair and improve disrupted attachment. Finally, the largest effect size for the differences between the groups of children for all variables was found in total parent–child attachment, further suggesting that alternative criminal sentencing provides added security for children of incarcerated parents.

10 Limitations

This study had a number of limitations that should be noted when interpreting findings. First, the samples were drawn from two non-profit agencies with relatively small numbers of clients. At the time of this study’s commencement, the alternative sentencing site was the only program of its kind in the state of Oklahoma and saw it’s first graduates in 2010. Because of this, the pool of potential graduate participants from this program was small. The other participating organization serves children who have or have had a parent in prison, but the agency serves more children with a parent currently in prison than children whose parents have been released and more children of incarcerated fathers than mothers. For this reason, the pool of potential participants from this agency was small. This small sample size reduced the power to detect differences between outcomes for the two groups of children studied. Future research should strive for a larger sample drawing matched comparison groups so that the characteristics of the sample are similar. Selecting a matched sample would help ensure that extraneous factors such as potential differences in age, gender, and parental criminal history are controlled in the comparison. Finally, because of the population available at the alternative sentencing site, study demographics contained a high level of White participants and a lower percentage of other ethnicities, which are known to be over represented in prison populations (Glaze and Herberman 2013).

The results of this study could also have been impacted by geographical location. This study took place in the United States in a state characterized by high incarceration rates overall, and more importantly, in the state with the most women in prison per capita nationwide. Other countries or states with differing incarceration rates and correctional structures might find different results.

Participant involvement with the agencies where participants were accessed may have impacted the child outcomes targeted by this study. Children whose mothers were recently incarcerated were involved in a supportive after school and summer camp program designed to teach children of prisoners self-efficacy and other life skills. This program could mitigate some of the negative effects of parental incarceration. Furthermore, parents and caregivers who sign up for this type of program may represent a sample that is skewed toward more competent and functioning families. The alternative sentencing site that participated in this study offers a rare prison diversion environment with numerous programs and services that benefit its clients. This unique program does not represent every alternative sentencing program, though the present study’s findings present a positive prospective of its model in terms of child outcomes.

10.1 Implications for Practice & Directions for Research

The results of this study indicate that alternative criminal sentencing for non-violent mothers may produce more positive outcomes for their children than traditional sentencing alone. With high incarceration rates nationally and research asserting parental incarceration may affect children’s likelihood of developing a range of adverse outcomes, how to positively impact children of prisoners is a relevant concern. This concern does not only extend to agencies working with children and offenders or researchers interested in the effects of parental incarceration on children. Ultimately this concern extends to each member of the state of Oklahoma, as the burden to the state and federal economy is potentially exacerbated with each repeated parental incarceration.

The fundamental conclusion of this study is that children may fare better when their mothers receive alternative criminal sentencing as opposed to incarceration. Though incarceration is a complex issue, the findings of this study suggest that treatment for mothers may be an effective way to reduce future crime in terms of both the offenders and their children. This understanding may enable policy makers and government agencies to sentence non-violent offenders with fewer negative effects on children of prisoners’ outcomes. With respect to public policy, these findings, if confirmed elsewhere, would suggest that funding diversion and alternative sentencing programs like the one in this study is a more effective use of taxpayer dollars and, perhaps, a more sound crime reduction approach longitudinally. Knowing that behavioral problems and disrupted parent–child attachment may negatively affect a child’s life trajectory and that attachment security may predict social competence and problem solving in children, affecting at-risk children’s behavior and attachment through creating positive change in their parents may be an effective prevention method. Therefore, allowing more non-violent female offenders who have no other options in the department of corrections to serve an alternative sentence may not only positively impact children enduring parental incarceration in the short term, but may ultimately reduce the likelihood of incarceration of future generations.

In light of the findings, further research is warranted. Additional studies with further variables and larger sample sizes are needed to examine the potential of parental alternative criminal sentencing to yield better child outcomes than parental incarceration. Gender and other demographic differences in children’s responses should be explored. Again, sample selection where comparative groups are matched would provide better control. Younger children should be examined, as their patterns of behavior and attachment are more likely to have been established immediately prior to their mother’s incarceration. Fathers should also be considered, and the effects of paternal and maternal alternative criminal sentencing should be contrasted. As in the current study, future research should continue to examine the effects of parental incarceration and parental alternative criminal sentencing from both the child and parent’s perspectives. Although it was beyond the scope of this study, it would prove useful to include a teacher or mentor report form on children’s various outcomes, such as behavior. A longitudinal research design with more alternative criminal sentencing programs would go a long way in helping to understand the differences between these two groups of children as well.

Understanding the mental health conditions of mothers in future studies would also prove valuable, as a mother’s mental health may be critical to the overall wellbeing of her children. With the prevalence of dual diagnosis, the influence of a mother’s mental health is one worth considering. Alternative sentencing for non-violent offenders generally includes therapy, usually the completion of a drug treatment or rehabilitation program. In the case of the alternative criminal sentencing program participating in the current study, mothers received gender-responsive trauma informed substance abuse treatment along with cognitive behavioral therapies. These therapies may have improved not only the women’s drug dependencies but also the overall condition of their mental health. This improved mental health may or may not have impacted their children’s outcomes. When testing the association between maternal alternative sentencing and children’s outcomes, future studies should control for mother mental health as a covariate through matching and statistical modeling.

Recommendations for future research also include utilizing different methods of research. Studies within the literature review conducted on children of incarcerated parents are primarily quantitative and may involve secondary analysis of data (Murray and Farrington 2005; Phillips and Gates 2011). By utilizing mixed methods, both qualitative and quantitative designs, which might include interviews and focus groups, researchers could possibly gain more in-depth insight into children’s differentiating experiences and outcomes based on parental sentencing.

11 Conclusions

This study found evidence suggesting that treating parents’ problems positively affects the outcomes of their children. Consistent with Murray and colleagues’ (2014) findings that risks for children are minimized when the focus of a parent’s incarceration is on offender rehabilitation rather than punitive punishment, the findings of this research led to the conclusion that parental alternative criminal sentencing may be healthier for children of incarcerated parents when compared to traditional sentencing. It also suggests that the documented positive effects of alternative sentencing and treatment for offenders spill over to their children. Children in this study with mothers who received alternative criminal sentencing fared better than children with mothers who had been recently imprisoned in terms of behavior and attachment. Though further research is needed to better understand the distinct relationship between parents’ differentiating experiences within the criminal justice system and their children’s outcomes, the results of this study ultimately present a case for continued commitment to alternative sentencing for non-violent mothers in the state of Oklahoma.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Agnew, R. (2006). General strain theory: Current status and directions for further research. Taking stock: The status of criminological theory. (pp. 101–123). Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Loss. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss. New York: Basic Books.

Bussell, T.J. (2014). The effect of parental incarceration on high school outcomes. Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Full Text: Social Sciences. (1426647436).

Carson, E. A., & Golinelli, D. (2013). Prisoners in 2012: Trends in admissions and releases 1991–2012. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Carson, E.A. & Sabol, W.J. (2012). Prisoners in 2011. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p11.pdf.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013a). Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. http://www.cdc.gov/ace/index.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013b). Data & statistics: Prevalence. Austism Information Center. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html.

Dallaire, D. H. (2007). Incarcerated mothers and fathers: a comparison of risks for children and families. Family Relations, 56(5), 440–453.

Dallaire, D., & Wilson, L. (2010). The relation of exposure to parental criminal activity, arrest, and sentencing to children’s maladjustment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(4), 404–418.

Family Children’s Services of Tulsa (2013). Women in recovery. Retrieved October 1, 2013, from Family Children’s Services of Tulsa: http://www.fcsok.org/services/women-in-recovery/.

Geller, A., Garfinkel, I., Cooper, C. E., & Mincy, R. B. (2009). Parental incarceration and child well-being: implications for urban families. Social Science Quarterly, 90(5), 1186–1202.

George Kaiser Family Foundatation (2013) Women in recovery. [electronic resource] Retrieved from: http://www.gkff.org/areas-of-focus/female-incarceration/women-in-recovery.html.

Glaze, L.E. & Herberman, E.J. (2013). Correctional populations in the United States, 2012. Lauren E. Glaze and Erinn J. Herberman [Washington, D.C.]: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics 2013.

Glaze, L.E. & Maruschak, L.M. (2010). Parents in prison and their minor children [electronic resource]. / Lauren E. Glaze and Laura M. Maruschak. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 2008. (Original work published 2008).

Gullone, E., & Robinson, K. (2005). The inventory of parent and peer attachment—revised (IPPA-R) for children: a psychometric investigation. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 12(1), 67–79.

Harris, Y. R., Graham, J. D., & Carpenter, G. (2010). Children of incarcerated parents: Theoretical, developmental, and clinical issues. New York: Springer Pub. Co.

Hser, Y., Evans, E., Li, L., Metchik-Gaddis, A., & Messina, N. (2014). Children of treated substance-abusing mothers: a 10-year prospective study. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(2), 217–232.

Jimenez, C.C. (2014). The relationship between parental incarceration and incarceration. Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Full Text: Social Sciences. (1427361927).

Kinner, S. A., Alati, R., Najman, J. M., & Williams, G. M. (2007). Do paternal arrest and imprisonment lead to child behaviour problems and substance use? A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 48(11), 1148–1156.

Murray, J., & Farrington, D. P. (2005). Parental imprisonment: effects on boys’ antisocial behaviour and delinquency through the life-course. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 46(12), 1269–1278.

Murray, J., & Farrington, D. P. (2008). Parental imprisonment: long-lasting effects on boys’ internalizing problems through the life course. Development and Psychopathology, 20(1), 273–290.

Murray, J., Farrington, D. P., & Sekol, I. (2012). Children’s antisocial behavior, mental health, drug use, and educational performance after parental incarceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 175–210.

Murray, J., Bijleveld, C. C. J. H., Farrington, D. P., & Loeber, R. (2014). Effects of parental incarceration on children: Cross-national comparative studies. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Oklahoma Department of Corrections (2012). Did you know: Facts & frequently asked questions. Oklahoma Department of Corrections. Retrieved from: http://www.doc.state.ok.us/newsroom/publications/did_you_know.htm.

Oklahoma Department of Corrections (2014). Facts at a glance. Oklahoma Department of Corrections. Retrieved from: https://www.ok.gov/doc/documents/DOC_Facts_At_A_Glance_June%202014.pdf.

Pearson, R. (2009). Rural alternative sentencing: Variables that influence the substance abuse offender’s success (Order No. AAI3342451). Available from PsycINFO.

Pew Center on the States (2010). Collateral costs: Incarceration’s effect on economic mobility. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts. : http://www.pewstates.org/uploadedFiles/PCS_Assets/2010/Collateral_Costs(1).pdf.

Pew Research Center for the People and the Press. (2004). The 2004 political landscape: Evenly divided and increasingly polarized. Washington: Pew Charitable Trusts.

Phillips, S. D., & Erkanli, A. (2008). Differences in patterns of maternal arrest and the parent, family, and child problems encountered in working with families. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(2), 157–172.

Phillips, S., & Gates, T. (2011). A conceptual framework for understanding the stigmatization of children of incarcerated parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(3), 286–294.

Phillips, S. D., Gleeson, J. P., & Waites-Garrett, M. (2009). Substance-abusing parents in the criminal justice system: does substance abuse treatment improve their children’s outcomes? Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 48(2), 120–138.

Poehlmann, J. (2005). Representations of attachment relationships in children of incarcerated mothers. Child Development, 76(3), 679–696.

Poehlmann, J., Dallaire, D., Loper, A., & Shear, L. D. (2010). Children’s contact with their incarcerated parents: research findings and recommendations. American Psychologist, 65(6), 575–598.

Roettger, M. E., & Swisher, R. R. (2011). Associations of fathers’ history of incarceration with sons’ delinquency and arrest among Black, White, and Hispanic males in the United States. Criminology, 49(4), 1109–1147.

Sharp, S.F., Pain, E., & Oklahoma Commission on Children and Youth. (2010). Oklahoma Study of Incarcerated Mothers and Their Children.

Sharp, S.F., Jones, M.S., & McLeod, D.A. (2014). A study of incarcerated mothers and their children - 2014. The University of Oklahoma, Department of Sociology. Oklahoma Commission on Children and Youth, George Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Oklahoma Department of Corrections.

Shaw, M. (1992). Issues of power and control: women in prison and their defenders. British Journal of Criminology, 32(4), 438–452.

Shlafer, R. J., & Poehlmann, J. (2010). Attachment and caregiving relationships in families affected by parental incarceration. Attachment & Human Development, 12(4), 395–415.

Spivak, A. L., & Sharp, S. F. (2008). Inmate recidivism as a measure of private prison performance. Crime and Delinquency, 54(3), 482–508.

Sroufe, L., Carlson, E., & Shulman, S. (1993). Individuals in relationships: Development from infancy through adolescence. In D. C. Funder, R. D. Parke, C. Tomlinson-Keasey, & K. Widaman (Eds.), Studying lives through time: Approaches to personality and development (pp. 315–342). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Tasca, M., Turanovic, J. J., White, C., & Rodriguez, N. (2014). Prisoners’ assessments of mental health problems among their children. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(2), 154–173.

Turney, K. (2014). Stress proliferation across generations? Examining the relationship between parental incarceration and childhood health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55(3), 302–319.

Wexler, H. K., Melnick, G., Lowe, L., & Peters, J. (1999). Three-year reincarceration outcomes for Amity in-prison therapeutic community and aftercare in California. Prison Journal, 79(3), 321–336.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This manuscript is based upon the first author’s master’s thesis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 217 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fry-Geier, L., Hellman, C.M. School Aged Children of Incarcerated Parents: the Effects of Alternative Criminal Sentencing. Child Ind Res 10, 859–879 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9400-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-016-9400-4