Abstract

This paper presents data from a representative Spanish sample of children (N = 5934) in the first year of compulsory secondary education. Data were collected using four different psychometric instruments for measuring adolescents’ self-reported well-being, and a series of questions on children’s objective life situations, and another set of questions that explored respondents’ opinions, perceptions and evaluations. All the items were translated into the four different co-official languages in the different autonomous regions and cities that compose Spain. Three of the psychometric instruments used as indicators of subjective well-being are widely-known and have been used on adolescent populations in different countries; they have also been validated in the Spanish context in previous research. One (the SLSS) was specifically designed for children and adolescents aged 8 to 18. Another (the PWI) was initially designed for adults, but has been used with adolescents in different countries, and previous results suggest it is well understood and performs well with populations aged 12–18. The third well-known instrument used is a single-item scale on overall life satisfaction. The fourth instrument comprises an additional list of items on satisfaction with different aspects or domains in children’s lives. A composite synthetic Index, the GICSWB (General Index of Children’s Subjective Well-Being), was calculated using the values resulting from these psychometric instruments. The results of this Index are presented, showing different situations and perceptions in children’s lives that are related to significantly lower subjective well-being among the children involved when compared to those not involved in the same situations or perceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Systems of social indicators to assess social situations and social changes started to be adopted during the 1960s after the silent but far-reaching revolution took place that many call the social indicators movement. Bauer’s edited book (1966) was considered the breaking point. After his book, the measurement of subjective social realities has become a major challenge for social sciences, and the assessment of social changes has been assumed that must include not only objective indicators, but also subjective (Casas 2011).

Ben-Arieh (2008) points out that the development of the child indicators movement is a more recent but increasing phenomena, and although a few “State of the Child” publications appeared early, between 2005 and 2006 twice as many reports were published that in the entire decade of the 1980s, and dozens of data series and indicators are already available (Bradshaw et al. 2007). However, subjective indicators based on self-reported information from children have a much more brief history and only very recently have started to be taken into account as an important and different (and often complementary) perspective of the state of children. In fact, only very few international databases exist with data provided by children themselves—e.g. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) (www.hbsc.org) and Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) (www.oecd.org/pisa). These databases include a limited number of countries, mostly developed countries. Additionally, the only psychometric scale assessing well-being included in a few of the international databases is the single-item scale named the “Cantril ladder” (Cantril 1965).

UNICEF’s study coordinated by Adamson (2007) marked an important step toward the articulation of objective and subjective indicators for understanding children’s living situations in different countries. The study dealt with five major domains for children’s well-being, namely material well-being, health and safety, educational well-being, young people’s relationships, behaviours and risks, and subjective well-being. However, that pioneer study considered “subjective well-being” as a separate domain in life, rather than including a subjective perspective in each domain.

O’Hare and Gutierrez (2012) have recently reviewed how indicators have been combined into comprehensive composite indices to provide a more concise picture of how children are faring. These authors conclude that only education, health and material well-being seem to be agreed as key domains in almost all of the studies examined. Which are the other relevant life domains for children and adolescents well-being is still an unsolved debate. An important point is, however, that when children are asked, they frequently offer new domains, not reported in the traditional systems of indicators (O’Hare and Gutierrez 2012). Some recent publications include proposals to add news satisfaction domains to some of the existing multi-item instruments (e.g., Tomyn and Cummins 2011; Casas et al. 2011, 2012). A need remains for more studies to analyze the reliability and relevance of multi-item and multi-domain instruments for collecting children’s self-reports in order that the results might be used as subjective indicators in the international arena.

According ISCWeB (International Survey of Children’s Well-Being, promoted by the International Society for Child Indicators http://childrensworlds.org/why-the-study) one of the most important factors in assessing whether a particular environment is conducive to children attaining their best potential is the perception of their own subjective sense of well-being. If we hope to improve children’s well-being and their prospects of attaining to their full potential, we must first assess and measure their well-being. This, so the assumption, is best done by asking children directly and by allowing them to give an assessment of their own perception of their well-being (ISCWeB 2010).

The purpose of child well-being indices is to distil large amounts of data on children in ways that can be easily communicated to and used by policy makers and the public (Vandivere and McPhee 2008). In order to compare children’s well-being across cultures, languages and/or countries there is an increasingly more apparent need for indicators systems to include relevant subjective indicators that provide information regarding children’s self-assessment of their lives. Initial testing like that promoted by UNICEF Report Card 7 (Adamson 2007) has stimulated international debate, reflecting the potential interest in this field.

That said, one of the key points in the present debate is that the use of a one-item scale as the only indicator of children’s subjective well-being (e.g. Cantril’s leader, used in Report Card 7) is too weak a solution to the challenge. Very few empirical tests have been published with results obtained from children using more than one instrument in different countries, languages or cultural contexts—particularly multi-item instruments. Furthermore, with only a few exceptions, most of the research results available are from the English-speaking world.

This paper uses a good part of the questionnaire proposed for the 12-year-old children by the ISCWeB and has collected additional data using different psychometric instruments for measuring adolescents’ self-reported well-being. The questionnaire includes a series of questions on children’s objective life situations, and another set of questions that explored respondents’ opinions, perceptions and evaluations. All the items were translated into the four different co-official languages of the different Spanish regions. The languages are Castilian-Spanish, Catalan, Basque and Galician. Data were collected in the 17 different CCAA (Comunidades Autónomas = Autonomous Regions) and two autonomous cities (Ceuta and Melilla, in Northern Africa) that comprise Spain. The questionnaire was pilot tested in each language before adoption of the final version.

Three of the psychometric instruments here used are widely-known and have been used on adolescent populations in different countries. One of these, the SLSS (Huebner 1991a, b), was specifically designed for children and adolescents aged 8 to 18. Another, the PWI (Cummins et al. 2003), was initially designed for adults, but has been used with adolescents in different countries, and previous results suggest it is well understood and performs well with populations aged 12–18. The other well-known instrument used was a single-item scale on overall life satisfaction, which, following the proposal by Campbell et al. (1976), has become widely-used in all kinds of research in this field, although with different wordings. The fourth instrument consists of an additional list of items on satisfaction with different aspects or domains in children’s lives, designed specifically for this research, taking into account they are not included in the referred psychometric scales.

It is well known that available data for use as indicators of children’s subjective well-being are very scarce in the international arena—and testing their functioning in multicultural and multi-linguistic contexts poses quite a challenge.

By asking children questions through a questionnaire we have adopted the conceptual position that children are experts in their own lives and that they have the right to have their opinions and evaluations of their lives listened to and taken into account by adult-researchers (Kellett 2010; Mason and Danby 2011). Therefore, we consider children as key informants of their well-being and relevant agents in providing data on the realities they experience (Casas et al. 2012).

It is true that sometimes we cannot be sure that children’s understanding of one item is the same as adults’. At times children do not know what adults expect them to know. At other times, children do know, but express their knowledge through different words than those used by adults. However, what also often happens is that children take into account possibilities in their social reality that adults would not even be able to guess.

Therefore, the most honest reading of children’s answers should be to award credibility to their answers (at least the same credibility we usually give to adults’ answers in population samples), trying to understand their answers from their point of view. In any research collecting answers from children, we may find information that we cannot understand until we have carried out qualitative research with children. Only when children tell us in a language understandable for adults what they meant, we will perhaps be able to better understand their view of the world.

We assume the premise that psychometric multiple-item scales can be considered much more reliable and appropriated indicators of subjective well-being than single-item scales and therefore they are worth to be included in systems of indicators to evaluate aspects of children’s lives, particularly when adapted validated versions are available in different languages. In fact, several psychometric scales are available for cross-cultural research and have already been used and tested in previous comparative research with children 8-year-olds and elder (Casas 2011). At present, ISCWeB webpage offers a more updated version of the questionnaires than the one used in the present research.

Like in other countries, previous research results in Spain, restricted to population speaking one of the languages and with smaller non-representative samples, has shown that children’s answers offer sometimes unexpected results, that contradict adult’s stereotypes and believes about children’s life and children’s well-being (Casas 2011). We may expect that some of these unexpected results may appear repeated with the data from a representative sample, and therefore they will be useful for broader debates and to create a social and political attitude towards more regular and systematic data collection of children’s points of view about their own lives.

The goal of this study is to test instruments that can be used to construct systems of subjective indicators for children’s well-being. Indicators from these systems could ideally be used in broader systems using both objective and subjective indicators of children’s well-being, as was the case with Report Card 7. Tabulating an index of subjective well-being by combining different psychometric instruments and comparing its values with the values of situational variables based on information provided by children we aim to conduct a broad analysis of how the subjective well-being of Spanish children in the first year of ESO relates to different children’s living conditions and the diverse activities they participate in, and how subjective well-being may be influenced by the different perceptions and evaluations of children themselves at population level.

2 Methodology

2.1 Instruments

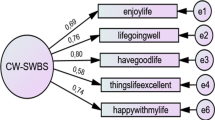

The administered questionnaire included the following three psychometric scales: a single-item scale on Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS), a 5-item version of the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS5) proposed by Huebner (1991a, b), and an 8-item scale on satisfaction with life domains, a variation on the Personal Well-Being Index created by Cummins et al. (2003), which we shall call the adapted PWI8 (PWI8adp) (Table 1).

It also incorporates 18 additional questions on satisfaction with aspects or domains of life, which share the same format as the PWI. These 18 items, together with the 8 of the PWI, can be grouped into eight broad life domains and an index calculated for each one (Table 2).

Scores for all items were collected using a 0–10 scale, following Cummins and Gullone’s (2000) recommendations, and scores for multi-item scales were transformed into a 0–100 scale to facilitate comparison.

Information was also collected about the school funding (state-run, mixed funded, private) and the geographical context of the school (rural, urban or semi urban: between 2,000 and 20,000 inhabitants), age, gender and place of birth of each child. The questionnaire also includes a series of questions on children’s life situations, and another set of questions that explores respondents’ opinions, perceptions and evaluations. Life situations reported by children were: recent changes in their lives, material and cultural belongings at home including access to Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), parents’ levels of education, living in one home or more, being in out-of-home care, adults in paid employment at home, having at list 1 week holiday away from home, receiving pocket money regularly, repeating school year, frequency of physical exercise, frequency of activities with their family, missing school because of illness. Children’s self-reported opinions, perceptions and evaluations were about: security in different contexts, feeling of being listened and taken into account, evaluation of how different people treats them, whether they have been told children have rights, qualities they aspire to, having enough space at home and enough space outdoors in their neighbourhood, worrying about money, perceiving their family as less or more wealthy than other families, feeling their time is well organized and feeling they are well treated by the doctor.

2.1.1 Personal Well-Being Index (PWI)

This scale was designed by Cummins et al. (2003) as part of the Australian Unity Wellbeing Index. Originally, it included seven items on satisfaction with different life domains. In this research, two additional items have been included, one on school satisfaction, as proposed by Tomyn and Cummins (2011), and another on satisfaction with time use, as proposed by Casas et al. (2011).

The wording of the items—excepting satisfaction with your health—has been slightly changed in order to make them more clearly understandable for the age of the intended sample. Satisfaction with your standard of living has been substituted by satisfaction with all the things you have, which is a similar wording to that in the PWI-SC (Cummins and Lau 2005). Satisfaction with your personal relationships has been substituted by satisfaction with your relations with other people in general. Satisfaction with your safety has been substituted by satisfaction with how secure you feel. Satisfaction with what you have achieved in life has been substituted by satisfaction with your opportunities in life. Satisfaction with feeling part of your community has been substituted by satisfaction with people living in the area you live in. Satisfaction with your future security has not been included. We will call the version used here PWI8adp.

The scale used has an end-labelled format, from completely dissatisfied (0) to completely satisfied (10), with a label also at the neutral point (5) not dissatisfied or satisfied. The addition of a neutral-point label was decided in order to make it more evident to children that there was a range of positive and negative values—we thought this would help them not to focus so much on the highest values of the scale.

The psychometric properties of the PWI have been published in several articles (see, for example, Lau et al. 2005; International Wellbeing Group 2006). Cronbach’s α was originally reported to lie between 0.7 and 0.8. The seven original domains form a single component and predict over 50 % of the variance for “satisfaction with life as a whole” (Cummins et al. 2004) with adult samples.

Cronbach’s α of the PWI8adp was .78. The scale shows a single component explaining 40.61 % of the variance.

2.1.2 Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS)

This scale was designed by Huebner (1991a) as a 7-item context-free one-dimensional scale. Up until 1994 it was tested on small samples of children 10 to 13-year-olds (N = 79) (Huebner 1991b) and 7 to 14-year-olds (N = 254) (Huebner 1991a) in the USA using a 4-point frequency scale (from never to almost always). Reported Cronbach alphas ranged from .73 (Terry and Huebner 1995) to .82 (Huebner 1991a; Huebner et al. 2003).

In Fogle et al. (2002) the scale is reported to use a 6-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree, and Cronbach’s alpha is reported at 0.86 (N = 160, 10–15-year-olds). Gilman and Huebner (1997) suggested caution with respect to assuming the comparability of scores across the two formats. Not all of the seven items on the original scale have always been found to make the same high contributions to the overall index of the scale (Terry and Huebner 1995).

After reviewing these results, for our questionnaire we decided on a 5-item, 5-point scale labelled from completely agree to completely disagree, which we shall call SLSS5.

Cronbach’s α of the SLSS5 in our sample was .80. The scale shows a single component explaining 60.99 % of the variance.

2.1.3 Single-Item Scale on Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS)

The importance of including a single-item scale on overall life satisfaction when studying SWB has been highlighted by Campbell et al. (1976). In our research, we included a question on Satisfaction with your overall life, using an end-labelled 0–10 scale from completely dissatisfied to completely satisfied. The translation of the item back into English is To what extent are you satisfied with your life as a whole?

2.1.4 List of Items on Satisfaction with Different Life Domains and Aspects of Life

The administered questionnaire included 18 further questions regarding respondents’ satisfaction with specific aspects of their lives, which, when added to the eight of the PWI8adp, can be grouped into eight domains. The answers to these questions, each on a scale of 0 to 10 points, allow us to calculate a satisfaction index for each of these domains, as detailed in Table 2.

Using a multiple regression analysis we explore whether each of these items contributes to explaining each of the three psychometric scales, and after eliminating those which do not contribute any explanation, we calculate an overall index which we will call Domain Satisfaction General Index (DSGI), by means of the simple arithmetic sum of the psychometric instruments, converted to a scale from 0 to 100.

2.2 Procedure

A two-stage cluster sampling design was used to select a representative stratified sample of Spanish children in the first year of ESO (Educación Secundaria Obligatoria = Compulsory Secondary Education). In the first stage, schools in each autonomous region or city (17 + 2) in Spain were stratified according to whether they were state-run, mixed funding or private, and whether they were located in urban (>20,000 inhabitants), semi urban (between 2,000 and 20,000) or rural (<2,000) environments, in order to calculate the minimum number of schools in each strata for the sample to be representative with less than 2 % error at a confidence level of 95 %. We then randomly selected the fixed number of schools in each stratum for the chosen region. The real margin of error in the sample assuming maximum uncertainty was 1.9 %.

At each school, we proceeded in accordance with the regular ethical guidelines for administering questionnaires to children in Spain and asked for the consent of the director.

When a school agreed to participate, we randomly selected two classes in the first year of ESO. We then asked for cooperation from the class teacher. Following approval, and as soon as the ethical and formal procedures were concluded, the children were asked for their cooperation and were informed that their data would be treated confidentially and that they were free to refuse. The questionnaires were group-administered in their regular classroom. One of their usual teachers and one or two researchers were present during administration of the questionnaires to answer any questions that arose.

2.3 Sample

The sample is composed of 5,934 children aged between 11 and 14 years-old. The 13 and 14-year-olds (19,4 %) are mainly children repeating a year, although some of them may be immigrants with a lower academic level than expected for their age and therefore placed in a lower year than other children of the same age. 11.2 % of the children in the sample reported they were not born in Spain. 78.2 % reported living in only one household with both parents; 14.1 % reported living in more than a household, regularly or occasionally; and 2.7 % reported living in a household NOT with their own family. We cannot understand the last figure without further qualitative research, as only 0.8 % of the children in Spain are at present in residential or foster care.

3 General Results

3.1 Analysis of Extreme Responses

Table 3 shows the responses of children to questions regarding different aspects or areas of their lives and all questions about satisfaction with life in general. For this last question, we see that, on the one hand, the more dissatisfied respondents represent only 1.7 % of the total, while, on the other hand, 80.3 % responded with a 9 or 10.

We also observe that three areas accumulate many more dissatisfied responses than others: Libraries in the area where you live, the pocket money you receiveFootnote 1 and the local police or police in the area where you live.

In adult populations it is known that those who are dissatisfied with their overall life are usually people with psychopathological problems, often of a depressive nature, with the exception of those who have an extremely pessimistic outlook. Further investigation is required to determine whether a parallel interpretation is valid for child or adolescent populations.

At the other extreme, we see that overall life satisfaction has a very high percentage of respondents who are completely satisfied, only surpassed by those who respond the same regarding their health, people living in the same household, other family members, things they have, friends, the space available in the house in which they live and the treatment they receive from the doctor. We observe that four of these seven aspects are relational, as is satisfaction with schoolmates, which also accumulates a very high percentage of very satisfied respondents, while two are considered in some studies as indicators of materialism (the things you have and the space available to you).

The three aspects with fewest completely satisfied respondents are the local police or police in the area where one lives, the libraries in the area where you live and marks received at school. Note that all of these correspond to external aspects of life. Aspects corresponding to more internal psychological life show that between 75 % and 77 % of subjects are completely satisfied (satisfaction with yourself, with your self-confidence, with the opportunities you have).

3.2 Gender Differences in Responses

Gender differences in subjective well-being have already led to much debate and generated conflicting research results. With regard to satisfaction with aspects or domains of life and the subjective well-being indices used in this study, Table 4 offers an overview of the diverse data obtained by respondent gender.

If we consider the 26 items on satisfaction, it is observed that, presumably due to the effect of large samples, almost all gender differences are significant except satisfaction with the area where you live, health, the use of time and things you do in your spare time. We see that in seven items scores are higher among boys (although only four significantly: freedom, appearance, satisfaction with yourself and self-confidence) and in 19 they are higher among girls (18 significant). Overall indices comprising life domains (the PWI8 and DSGI) also display a significantly higher subjective well-being among girls, although in absolute terms the differences are very small. By contrast, the context-free global indicators (i.e. those that do not evaluate well-being by domains: the OLS and SLSS5) display no significant differences between the genders.

These results seem to suggest that at this age both sexes tend to display a high level of life satisfaction, which is reflected in different aspects or domains according to sex, and that these “compensate” one another to leave no significant overall differences when “we look beyond individual domains” (the logic of context-free scales lies in capturing that “something else” from the classic gestalt principle that “the whole is more than the sum of its parts”).

In any case, it seems clear that whether there are gender differences in responses or not may be highly influenced by socio-cultural factors or those related to geographical environment, as in the values for some satisfactions no gender difference is detected in some CCAA, while in others the differences are very large.

3.3 The Structure of Well-Being: The Most Important Aspects and Domains

In this section we will explore which satisfactions, of the 26 considered in this study, and which satisfaction indices with life domains, of the 8 calculated, display a greater explanatory power for subjective well-being. For this, we have used different regression models, considering as dependent variables each of the three scales used: the OLS, SLSS5 and PWI8adp (Tables 5 and 7).

Twelve of the 26 items on satisfaction contribute significantly (and with a positive beta) to the OLS, the adjusted R2 being .519. The greatest contribution is by satisfaction with the opportunities you have in life (beta = .231), followed by satisfaction with yourself (beta = .147) and satisfaction with how secure you feel (beta = .146).

Moreover, 17 of the 26 items on satisfaction contribute significantly (and with a positive beta) to the SLSS5, the adjusted R2 being .411. It is worth noting that only ten of these items coincide with those which are explanatory for the OLS, therefore suggesting that the two scales measure very different facets of subjective well-being. The largest contribution in this case is also satisfaction with the opportunities you have in life (beta = .130), followed by satisfaction with all the things you have (.115) and satisfaction with how you are listened to (.105).

Finally, since the PWI8adp is calculated using 8 of the 26 items on this list, two regressions were conducted with the PWI8adp as dependent variable: one with only the eight items that comprise it and the other with the rest of the items. The first regression shows that the greatest explanatory power is found with satisfaction with the people in the area where you live (beta = .270). Regression with the other 18 items on the PWI8adp shows that all items except one (satisfaction with libraries in the area) contribute to subjective well-being as measured by this scale (adjusted R2 = .723), and the greatest explanatory power is found with satisfaction with yourself (beta = .169).

The comparative results are quite curious, due to the differences found in the items that contribute to explaining each psychometric scale. For example, satisfaction with interpersonal relationships, with friends and with use of time only contribute to the PWI8, but with high betas. Only satisfaction with libraries in the area where you live does not seem to contribute significantly to explaining any of the indicators of subjective well-being used here, which is why it was removed from subsequent calculations.

After analyzing the results of each of the items regarding satisfaction with aspects or domains of life, we proceeded to calculate the indices reported in Table 2, which reflect eight major life domains of children. In Table 6, we see that the highest means for the whole Spanish sample correspond to the index of satisfaction with health (93.27 out of 100), followed by the index of satisfaction with the home (92.50), and the index of satisfaction with organization of your own time (89.04). The lowest means correspond to the satisfaction index of area where you live (78.07), followed by the material satisfaction index (see note 1) (86.41). The three other indices display values of between 86 and 89 points: the index of satisfaction with interpersonal relationships (88.76), the personal satisfaction index (87.59), and the index of satisfaction with school (86.91).

Upon doing a regression of these indices on each of the three psychometric scales, we note that 6 of the 8 indices contribute significantly to explaining both overall life satisfaction (as measured by the OLS) and the SLSS5. The indices of satisfaction with interpersonal relationships and satisfaction with the area you live in do not show a significant contribution. The greatest explanatory power is shown by the personal satisfaction index in both cases (Table 7).

In contrast, only the index of satisfaction with the area you live in does not contribute significantly to explaining the version of the PWI8 used here, the index of satisfaction with interpersonal relationships displaying the greatest explanatory power, followed by the personal satisfaction index.

When repeating the regression on the PWI8adp with index of satisfaction with the area where you live recalculated excluding satisfaction with libraries, the contribution of this index becomes significant. This is therefore conclusive in the decision to not use this item for any subsequent calculations.

3.4 Indices of Satisfaction with Eight Life Domains

The eight indices of satisfaction with life domains form a consistent set of measurements, as they maintain significant and moderate correlations with each other, the highest being that observed between satisfaction with personal aspects and satisfaction with organization of time (Table 8).

Comparing these indices with some of the defining variables of the study sample, we observe the following (Table 6):

-

A significant decline in satisfaction in all domains with age (with two exceptions), and a clear leap between 11–12 year-olds and 13–14 year-olds; remember that the latter, in our sample, are mostly repeating students.

-

Girls score significantly higher than boys in indices of satisfaction with the home, with material possessions, with relationships, with the area they live in and with the school they attend. The remaining gender differences are not statistically significant.

-

Boys and girls born in Spain show significantly higher satisfaction with all life domains except for the area they live in, those not born in Spain being significantly more satisfied with this.

-

Students attending schools in semi-urban settings score significantly higher than those at other schools in indices for all domains except satisfaction with the home (which is not statistically significant) and satisfaction with health, where those from urban settings score higher (although the difference is not significant).

-

Students at state schools tend to be significantly more satisfied than those at mixed-funding or private schools when it comes to their relationships, health, organization of their time and personal aspects, while students at mixed-funding schools are significantly more satisfied with their home than those attending the other two types of school.

3.5 Subjective Well-Being According to Four General Indicators

We see once again that the three psychometric scales studied here maintain positive, high and significant correlations with one another (Table 9).

When used with large samples, these three scales are sometimes taken separately as population indicators of subjective well-being in childhood. However, their correlations are not high enough to suggest that they measure the same construct, and the choice of one or another therefore conditions the results obtained.

In view of the consistency of the eight indices presented, we decided to calculate their arithmetic mean out of 100 and use the resulting index, which we shall call the Domains Satisfaction General Index (DSGI), as an indicator of contrast between the three psychometric scales. We observe that this new indicator shows high correlations with the three scales, but particularly high with the PWI8adp, suggesting that the eight items they share carry great weight in the DSGI.

Moreover, we also note that all satisfaction indices for the eight domains maintain medium to high correlations with these scales, the highest being those of the two scales on domain-based satisfactions (PWI8adp and DSGI) with both the personal satisfaction index and the index of satisfaction with interpersonal relationships (Table 9). All correlations of these indices with both context-free scales are lower than their counterparts with domain-based satisfactions.

3.6 Results of the Four General Well-Being Indicators According to Population Characteristics and Other Variables

When testing to see whether one of the four indicators of subjective well-being displays significant differences depending on the value of other variables, we observe that the results of each indicator are quite similar, though not always.

Differences between boys and girls are statistically significant only for the PWI8adp and DSGI, the girls having higher scores. By age, 13 and 14 year-old adolescents (presumably all repeating a year) display significantly lower levels of well-being for all the indicators used.

Subjective well-being is significantly lower with the four indicators used among adolescents not born in Spain when compared with that of native students (Table 10).

Comparatively, significantly higher levels of subjective well-being are found among the semi-urban than among the urban or rural populations. Means differ significantly for the rural and urban populations.

The four indicators coincide in obtaining higher subjective well-being scores among students in state schools than among those at mixed-funding or private schools. However, the differences between students at state schools and the other two school types are only statistically significant for the PWI8adp and DSGI.

We find that boys and girls who responded I do not receive pocket money have significantly lower scores for subjective well-being than the rest of the population (Table 11).

Of the 1,921 respondents who do receive pocket money, when exploring whether the amount received displays a relationship with subjective well-being, we find to our surprise that each of the four indicators used gives different results (Table 11), reinforcing the idea that these indicators are sensitive to different contextual factors.

4 Results Using a Synthetic Index of Subjective Well-Being

4.1 Proposal for a General Index of Subjective Well-Being (GICSWB)

Despite the high correlation usually observed between the three psychometric scales used as indicators of subjective well-being, in the scientific literature it is found that they tend to present relatively different results depending on the characteristics of each sample and the socio-cultural environment in which data have been obtained. The same is true of this study. For example, context-free scales magnify the importance of the contribution made by personal satisfaction to overall subjective well-being. However, there is abundant scientific literature showing the importance of interpersonal relationships to adolescents’ subjective well-being, even if this aspect is only detected by the third scale, based on life domains. It would therefore be desirable to integrate the potential explanatory capabilities of each of these scales in a composite index.

It is for this reason that we have chosen to calculate what we will call the General Index of Children’s Subjective Well-Being (GICSWB), by adding together 3 of the psychometric scales used here (with a total of 31 items). Since the eight domains used to calculate the PWI8adp are included in the DSGI, to calculate the GICSWB we will use the OLS, SLSS5 and DSGI, the latter recalculated using the direct sum of the values of the remaining 25 items, divided by 2.5, after excluding satisfaction with the libraries in the area where you live, for the reasons given in Section 3.3. After adding together the overall scores of the 3 scales, we reconvert them on a scale of 0 to 100 points for easy visual comparison.

4.2 Levels of Subjective Well-Being Among Spanish First-Year Secondary School Students

Doubt has often been expressed regarding whether children of this age are able to discriminate between levels of satisfaction, given that they tend to provide extreme responses. The so-called life optimism bias leads many populations to answer any questions about satisfaction with aspects or domains of their lives with a much higher percentage of satisfied than dissatisfied responses, resulting in a non-normal distribution. In child and adolescent populations, it is suspected that this polarization is even more intensified and therefore higher percentages of extreme responses are observed than in adult populations; these do not, however, reflect an inability to discriminate.

In any case, our results follow the trend observed in all samples collected from adolescents in various Western countries, where mean subjective well-being at this age is higher than among the adult population of the same socio-cultural background and life optimism bias is even more pronounced than among adults.

Some authors have proposed eliminating individuals with constant extreme responses under the assumption that they must be unreliable. While we understand that this proposal is useful for small samples, in our case we considered that it deserved closer scrutiny. We shall see that their exclusion alters the results very little, given the sample size and the minimum percentages that include the two extreme responses.

A detailed analysis of the data obtained from the GICSWB raises doubts over the accuracy of arguments concerning children’s lack of ability to discriminate between multiscale responses and their lack of reliability. While it is true that a majority of our sample scored between 90 and 99 points out of 100 (51 %), only 1.7 % (N = 102) reached 100 out of 100. No respondents constantly marked 0 for the 31 items of the GICSWB; the lowest minimum score on the GICSWB was 10 out of 100 (one respondent) and only 1.8 % scored less than 50 out of 100 (Table 12). This opens the door to possible reflection that children of these ages respond differently to adults when facing an 11-point scale, although with more distinction than previously thought.

Without eliminating responses, the mean Spanish score on the PWIadp is 89.60 out of 100, and 86.94 on the GICSWB. These figures are well above the average expected in Western adult populations using the PWI, which is between 70 and 80 out of 100 (Cummins and Cahill 2000). This confirms the hypothesis that the child population has higher levels of life satisfaction than the population average, falling gradually until approximately 15 or 16 years of age. When deleting the 102 children with extreme constant answers on the GICSWB, mean overall scores decrease only slightly: 89.42 for the PWIadp (88.95 for boys and 89.88 for girls) and 86.72 for the GICSWB (86.46 for boys and 86.98 for girls). Deleting all subjects with extreme constant answers in only the PWIadp would mean diminishing the sample by 834 children, which is obviously too drastic an option. Even in this case means would not be that much lower, however: 87.89 for the PWIadp (87.43 for boys and 88.37 for girls) and 85.42 for the GICSWB (85.12 for boys and 85.73 for girls).

Given all these considerations, the composite index used here allows us to reach a clear conclusion: Spanish children in the first year of secondary school are mostly very satisfied with their lives.

On the basis of this finding, we will analyze to what extent children’s subjective well-being, evaluated using the GICSWB, varies significantly depending on the material and personal conditions of their lives, the activities they do, their perceptions and evaluations, and their aspirations.

4.3 General Results Using the GICSWB

The results show interesting significant differences when using the GICSWB to compare diverse characteristics of children’s lives and their different perceptions and evaluations.

Children with significantly higher subjective well-being are those that (the order is irrelevant):

-

Feel greater personal safety

When we compare children that completely agree they feel safe to all other answers on a 5-point Likert scale, the former display higher subjective well-being. This is the case with safety at home (F(1, 5547) = 768.46, p < .0005), walking through the streets in the city area they live in (F(1, 5783) = 454.61, p < .0005), or at school (F(1, 5828) = 859.22, p < .0005).

-

Feel they are listened to

When we compare children that completely agree that they are listened to with all other answers on a 5-point Likert scale, the former display higher subjective well-being. This is the case with participating in decisions at home (F(1, 5404) = 278.48, p < .0005), having their opinions asked by local authorities about important things for children (F(1, 5155) = 86.68, p < .0005) or being listened to and taken into account by their teachers (F(1, 5839) = 664.40, p < .0005).

-

Have experienced fewer recent important changes in their lives

When we compare children that had experienced important changes in their lives during the past year with those that had not, the latter display higher subjective well-being. This is the case with changes of parents or carers (F(1, 5734) = 124.41, p < .0005), of home (F(1, 5765) = 79.86, p < .0005), or of city they live in (F(1, 5755) = 32.05, p < .0005).

-

Consider that other people treat them well

When we compare children that completely agree that other people treat them well with all other answers on a 5-point Likert scale, the former display higher subjective well-being. This is the case with my parents treat me well (F(1, 5533) = 1060.84, p < .0005), my friends are usually nice to me (F(1, 5847) = 559.36, p < .0005), my schoolmates treat me well (F(1, 5819) = 931.702, p < .0005) and my teachers treat me well (F(1, 5852) = 838.87, p < .0005).

-

Have been told children have rights

When we compare children that completely agree they have been told children have rights with all other answers on a 5-point Likert scale, the former display higher subjective well-being. This is the case when they have been told about children’s rights in their family (F(1, 5542) = 403.07, p < .0005), at school (F(1, 5464) = 278.64, p < .0005) or by others (F(1, 5258) = 134.94, p < .0005). Children that answer yes when asked whether they have been told about the Convention on the Rights of the Child also show significantly higher subjective well-being than those that answer no (F(1, 5710) = 18.84, p < .0005).

-

Aspire more to relational values than materialistic values

Children that report high aspirations for relational values (9 or 10 on a 0–10 scale) and low aspirations for materialistic values (8 or less on a 0–10 scale) display higher subjective well-being than those reporting high aspirations for materialistic values and low aspirations for relational values (F(1, 2773) = 45.59, p < .0005). However, those children equally having very high aspirations for both relational and materialistic values display the highest scores in subjective well-being.

-

Do physical exercise or sport every day

When we compare children that report doing sports or physical exercise every day or almost every day with any other answer (from every day to never), the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5840) = 118.82, p < .0005).

-

Report doing daily activities together with their family

When we compare children that report doing daily activities together with their family every day with any other answer (from every day to never), the former display higher subjective well-being, whatever the activity may be: talking together (F(1, 5843) = 379.253, p < .0005), having fun together (F(1, 5780) = 573.23, p < .0005) or learning together (F(1, 5696) = 483.170, p < .0005).

-

Consider they have a space of their own at home

When we compare children that completely agree they have a space of their own at home with all other answers on a 5-point Likert scale, the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5524) = 453.91, p < .0005).

-

Consider there are enough spaces to play and enjoy themselves in the area they live in

When we compare children that completely agree there are enough spaces to play and enjoy themselves in the area they live in with all other answers on a 5-point Likert scale, the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5815) = 446.92, p < .0005).

-

Have not missed school recently because of illness

When we compare children that have never missed school in the last two months because of illness with any other answer (from never to every day), the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5598) = 47.73, p < .0005).

-

Have more material and cultural belongings at home

When we compare those children reporting to have the highest number of material or cultural belongings at home with children giving any other answer about the number of belongings, the former display higher subjective well-being. This is the case with number of bathrooms at home (F(1, 5818) = 16.80, p < .0005), number of cars (F(1, 5814) = 30.40, p < .0005) and number of books (F(1, 5734) = 9.36, p = .002). Additionally, when we compare children reporting that a newspaper is bought at their home every day or almost every day with any other answer, the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5746) = 13.78, p < .0005).

-

Parents have higher levels of education

When we compare children reporting that their father or mother finished higher education or university with those reporting parents with lower levels of education, the former display higher subjective well-being. This is the case with both the father (F(1, 5721) = 45.77, p < .0005) and the mother (F(1, 5743) = 60.55, p < .0005).

-

Attend schools in populations of between 2,000 and 20,000 inhabitants

When we compare children attending schools in semi-urban contexts with those in urban or rural contexts, the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5917) = 11.69, p = .001).

-

Live in only one home

When we compare children living in only one home with those living in any other kind of arrangement (i.e. living in two homes regularly or occasionally, living in residential care), the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5827) = 54.87, p < .0005).

-

Report two adults in paid employment living at home

When we compare children reporting two adults living at home in paid employment with those reporting living with adults in any other situation, the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5765) = 31.03, p < .0005).

-

Never worry about money

When we compare children reporting that they never worry about money with any other answer (from never to always), the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5630) = 85.77, p < .0005).

-

Had at least one week of holiday away from the home

When we compare children reporting that in the last year they have been on at least one week’s holiday away from home with those that have not, the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5799) = 66.27, p < .0005).

-

Feel their time is well organized

When we compare children that are very satisfied with their own organization of their time (9 or 10 on a 0–10 scale) with those giving any other evaluation (8 or less on a 0–10 scale), the former display higher subjective well-being. This is the case with satisfaction with my use of time (F(1, 5803) = 1435.84, p < .0005) and satisfaction with things I do in my leisure time (F(1, 5810) = 1263.11, p < .0005).

-

Receive regular pocket money from their parents

When we compare children reporting they get regular pocket money, be it weekly or monthly, with these that do not get pocket money or do not get it regularly, the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5867) = 12.49, p < .0005).

-

Report they are well treated when going to the doctor

When we compare children that are very satisfied with how they are treated when they go to the doctor (9 or 10 on a 0–10 scale), with those giving any other evaluation (8 or less on a 0–10 scale), the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5835) = 704.57, p < .0005).

-

Do not repeat a school year

When we compare the 13 and 14 year-olds, who are the ones presumably repeating a school year, with those in the school year corresponding to their age, the latter display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5802) = 150.03, p < .0005). This result is also influenced by the fact that subjective well-being tends to decrease with age during adolescence.

-

Were born in Spain

When we compare children reporting that they were born in Spain with those reporting they were not, the former display higher subjective well-being (F(1, 5902) = 50.94, p < .0005).

By contrast, among those with significant lower levels of subjective well-being are children that:

-

Are in care, in the public child protection system

When we compare children reporting they live in their family household with those reporting to live in care, the latter display lower subjective well-being (F(1, 5624) = 27.69, p < .0005).

-

Do not receive pocket money

When we compare children reporting not to receive pocket money with those reporting they do, the former display lower subjective well-being (F(1, 5867) = 131.17, p < .0005).

-

Have parents who did not finish primary education

When we compare children reporting that either of their parents did not finish primary education with those reporting that both parents did, the former display lower subjective well-being. This is the case with the father (F(1, 5721) = 44.68, p < .0005) and the mother (F(1, 5743) = 42.25, p < .0005).

-

Report that at home no adult is in paid employment

When we compare children reporting that no adult at home is in paid employment with those giving any other answer, the former display lower subjective well-being (F(1, 5765) = 59.58, p < .0005).

-

Do not have access to ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies)

When we compare children reporting that they have no access to ICTs with those reporting they have, the former display lower subjective well-being. This is the case with having a computer that can be used when needed (F(1, 5878) = 123.97, p < .0005), having Internet (F(1, 5863) = 52.23, p < .0005) or having a mobile phone (F(1, 5840) = 19.22, p < .0005).

-

Perceive their family as less or much less wealthy than other families

When we compare children that perceive their family as being less or much less wealthy than the other families in the area they live in with any other perception (equally, more or much more wealthy), the former display lower subjective well-being.(F(1, 5157) = 421.60, p < .0005).

-

Do not feel safe

When we compare children that completely disagree they feel safe with all other answers on a 5-point Likert scale, the former display lower subjective well-being. This is the case with safety at home (F(1, 5546) = 72.07, p < .0005), walking through the streets in the city area they live in (F(1, 5782) = 348.487, p < .0005), or at school (F(1, 5827) = 307.604, p < .0005).

-

Feel they cannot participate in decisions taken at home

When we compare children that disagree or completely disagree that they can participate in decisions taken at home with all other answers on a 5-point Likert scale, the former display lower subjective well-being (F(1, 5404) = 436.198, p < .0005).

-

Have changed parents or carers during the last year

When we compare children reporting they have changed parents or carers during the last year with those reporting they have not, the former display lower subjective well-being (F(1, 5734) = 124.412, p < .0005).

5 Discussion

Results presented here are the answers of a representative sample of Spanish children to a questionnaire based in a good part on the one proposed for the 12-year-old children by the ISCWeB and therefore these results are not based in any secondary source of information. ISCWeB project tries to overcome some of the well-known limitations of the existing databases including subjective information from children, as identified for example in Hanafin and Brooks (2009).

The questionnaire included information organized in eight life domains, and included several items on satisfaction related to each of these domains. A satisfaction index has been calculated for each domain: home, material belongings, interpersonal relationships, the area living in, health, time organization, school and personal satisfaction. These domain satisfaction indices, together with two subjective well-being psychometric scales with very different characteristics have been combined into a comprehensive General Index of Children’s Subjective Well-Being (GICSWB), which has proved to be robust and appropriate for comparative purposes.

The domains included in the ISCWeB can’t be considered exhaustive, because broader proposals can be found in the existing literature, like for example in Moore and Theokas (2008). The domains here included should be considered a starting point to explore children’s lives from their own perspective, provided that a questionnaire for children of this age group can’t be longer if we want to guarantee high cooperation during its administration.

Children have informed us about their perceptions and evaluations of the environment in which they live, their activities, their aspirations and their well-being. It is therefore not surprising that some data may not match the general attributions Spanish adults have about how children live and think. It has been noted in numerous previous studies that humans often attribute features of reality to our thoughts, perceptions, evaluations and stereotypes, and although it is not possible to test this empirically, it has concrete implications: If men define situations as real , they are real in their consequences (Thomas and Thomas 1928).

In recent years, as scientific research has begun to consider the opinions and evaluations of the child population, there has been a notable increase in unexpected results, especially with data collected from 12 to 16 year-old adolescents. Much of this information had simply never been asked of boys and girls of that age, but even researchers, as adults, “assumed we knew” what their answers would be. Casas (2011) provides some examples of this type of unexpected data, some of which are also supported by the results of this study.

Results from this representative sample display much higher PWI scores (using the PWI8adp) than any previous Spanish research conducted on adolescents, presumably related to the fact that the mean age is much lower. This age group also show a much higher optimistic bias than any of the available adults’ sample. This survey used four psychometric scales to evaluate subjective well-being. Some very interesting new evidence arose out of our data, the most surprising probably being that children, despite their extremely high scores, seem to discriminate between answers fairly well, although probably in a different way than adults do. Using a comparative composite Index, the GICSWB, only 1.7 % scored 100 out of 100, although 51 % of students scored from 90 to 99.9, and only 1.8 % scored less than 50.

Results using this composite index allow us to identify a diversity of children’s life situations and of children’s perceptions and evaluations that coincide with significantly lower subjective well-being among these children when compared with other children of the same age not involved in the same situations or having the same perceptions or evaluations.

Many of our results are intuitive and consistent with previous results using objective indicators: All situations related to inequality (Bradshaw and Richardson 2009) coincide with a significant lower score in children’s subjective well-being. Other results are consistent with qualitative research developed in a few countries, particularly in relation to the importance of having enough material resources and of safety and security for children’s well-being (Fattore et al. 2009; Andresen and Fegter 2011).

In summary, some personal perceptions and feelings of the child are shown to be very important for subjective well-being of Spanish children at this age. This is the case with the feeling of personal safety, the feeling they are listened to, the consideration that other people treat them well, considering they have a space of their own at home, considering there are enough spaces to play and enjoy themselves in the are they live in and the feeling their time is well organized.

Some living experiences or conditions of the context of living represent positive factors in the subjective well-being of the surveyed Spanish children. This is the case with having educated parents, living in only one home, living in semi-urban settings, having a certain level of material and cultural belongings, having two adults living at home in paid employment, having at least 1 week’s holiday away from home every year, having regular pocket money, not repeating the school year, not having missed school recently because of illness and being born in Spain. By contrast, some experiences or conditions of the context of living have a negative impact on children’s well-being, as is the case with having experienced recent important changes in their lives, not having access to ICTs, or being in care in the child protection system. Additionally, children that perceive they are well treated when going to the doctor display higher subjective well-being than those that do not.

The frequency of some activities also shows a positive relationship with subjective well-being: those children doing physical exercise every day or doing daily activities together with their family display higher subjective well-being.

Aspirations have proved to be a more complex phenomenon. Children with equally very high aspirations for materialistic and relational values display the highest subjective well-being. Children that aspire much more to relational than materialistic values score significantly higher in subjective well-being than those that aspire much higher to materialistic than relational values, consistently with previous research (Casas et al. 2008).

Children that never worry about money also display higher subjective well-being than those that do not. Apparently, worrying about money is unrelated to the objective financial situation of the family, indicating that what is relevant here is the child’s attitude towards money.

Surprisingly, those children that report having been told that children have rights display higher subjective well-being than those that do not.

Overall, many of these results were expected, whereas others were new or unexpected. However, all of them are the result of directly asking children about their activities, perceptions and evaluations (i.e. satisfactions) regarding their lives, allowing us to increase our knowledge of children’s social reality. We have also identified variables that can potentially be used as indicators of subjective well-being in future research in the Spanish context and hopefully also in other countries. The procedure used may be of interest to take into account in other countries where a comprehensive composite index could be useful. These indicators should be taken into account to plan public policies, particularly policies addressed at or involving children. They should also be used to evaluate the impact of such policies on children’s well-being.

Notes

The results for this question include the entire population that responded to it, regardless of whether they receive pocket money or not: it would therefore seem logical to expect that those who do not receive it are more dissatisfied with it than those who do, and those who receive it express their satisfaction according to the amount they receive. However, while the first expected result is met, satisfaction shows no relation to the amount of pocket money received, but rather is related to the fact of receiving it REGULARLY or not.

References

Adamson, P. (Ed.) (2007). Child poverty in perspective: An overview of child well-being in rich countries. Report Card 7. Innocenti Research Centre. UNICEF.

Andresen, S., & Fegter, S. (2011). Childrne growing up in poverty and their ideas on what constitutes a good life: childhood studies in Germany. Child Indicators Research, 4, 1–19.

Bauer, R. A. (Ed.). (1966). Social indicators. Cambridge (Mass.): The M.I.T. Press.

Ben-Arieh, A. (2008). The child indicators movement: past, present and future. Child Indicators Research, 1, 3–16.

Bradshaw, J., & Richardson, D. (2009). An index of child well-being in Europe. Child Indicators Research, 2, 319–351.

Bradshaw, J., Hoscher, P., & Richardson, D. (2007). An index of child well-being in the European Union. Social Indicators Research, 80(1), 133–177.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rogers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. Russell Sage: Nueva York.

Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick (N.J.): Rutgers Univ. Press.

Casas, F. (2011). Subjective social indicators and child and adolescent well-being. Child Indicators Research, 4(4), 555–575.

Casas, F., Figuer, C., González, M., & Malo, S. (2008). Las aspiraciones materialistas y su relación con el bienestar psicológico y otros constructos psicosocials en dos muestras de adolescentes catalanes. Revista de Psicología Social, 23(2), 229–241.

Casas, F., Sarriera, J. C., Alfaro, J., González, M., Malo, S., Bertran, I., et al. (2011). Testing the personal wellbeing index on 12–16 year-old adolescents in 3 different countries with 2 new items. Social Indicators Research, 105, 461–482. doi:10.1007/s11205-011-9781-1.

Casas, F., Baltatescu, S., Bertrán, I., González, M., & Hatos, A. (2012). School satisfaction among adolescents: testing different indicators for its measurement and its relationship with overall life satisfaction and subjective well-being in Romania and Spain. Social Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0025-9.

Casas, F., González, M., Navarro, D., & Aligué, M. (2012). Children as advisers of their researchers: assuming a different status for children. Child Indicators Research. doi:10.1007/s12187-012-9168-0.

Cummins, R. A., & Cahill, J. (2000). Avances en la comprensión de la calidad de vida subjetiva. Intervención Psicosocial, 9(2), 185–198.

Cummins, R.A., & Gullone, E. (2000). Why we should not use 5-point Likert scales: The case for subjective quality of life measurement. Proceedings, Second International Conference on Quality of Life in Cities (pp. 74–93). Singapore: National University of Singapore. http://acqol.deakin.edu.au/instruments/PWI/2000-QOL_in_Cities-Likert_Scales-ss.doc.

Cummins, R.A., & Lau, A.L.D. (2005). Personal Wellbeing Index – School Children (PWI-SC) (English) 3rd edition. Manual. Reviewed May 2006. http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/instruments/PWI/PWI-school.pdf.

Cummins, R. A., Eckersley, R., Pallant, J., Van Vugt, J., & Misajon, R. (2003). Developing a national index of subjective wellbeing: the Australian unity wellbeing index. Social Indicators Research, 64, 159–190.

Cummins, R.A., Eckersley, R., Lo, S.K., Okerstrom, E., Hunter, B., Davern, M. (2004). Australian unity wellbeing index: Cumulative Psychometric record. Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, School of Psychology, Deakin University. http://acqol.deakin.edu.au/index_wellbeing/index.htm.

Fattore, T., Mason, J., & Watson, E. (2009). When children are asked about their well-being: towards a framework for guiding policy. Child Indicators Research, 2, 57–77.

Fogle, L. M., Huebner, E. S., & Laughlin, J. E. (2002). The relationship between temperament and life satisfaction in early adolescence: cognitive and behavioral mediation models. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 373–392.

Gilman, R., & Huebner, E. S. (1997). Children’s’ reports of their well-being: convergence across raters, time, and response formats. School Psychology International, 18, 229–243.

Hanafin, S., & Brooks, A. M. (2009). From rhetoric to reality: challenges in using data to report on national set of child well-being indicators. Child Indicators Research, 2, 33–55.

Huebner, E. S. (1991a). Initial development of the student’s life satisfaction scale. School Psychology International, 12, 231–240.

Huebner, E. S. (1991b). Correlates of life satisfaction in children. School Psychology Quaterly, 6, 103–111.

Huebner, E.S., Suldo, S.M., Valois, R.F. (2003). Psychometric properties of two brief measures of children’s life satisfaction: The Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS) and the Brief Multidimensional Students Life Satisfaction Scale (BMSLSS). Indicators of Positive Development Conference. March, 12–13.

International Wellbeing Group (2006). Personal Wellbeing Index – adult - manual, 4th version. Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University. http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/instruments/wellbeing_index.htm.

ISCWeB (2010). International survey of children’s well-being. Retrieved on 1st December 2012 from http://www.childrensworlds.org. Initiators: ISCI, UNICEF and World Vision.

Kellett, M. (2010). Rethinking children and research. Attitudes in contemporary society. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

Lau, A. L. D., Cummins, R. A., & McPherson, W. (2005). An investigation into the cross-cultural equivalence of the personal wellbeing index. Social Indicators Research, 72, 403–430.

Mason, J., & Danby, S. (2011). Children as experts in their lives: child inclusive research. Child Indicators Research (Special Issue), 4(2), 185–189.

Moore, K. A., & Theokas, T. (2008). Conceptualizing a monitoring system for indicators in middle childhood. Child Indicators Research, 1, 109–128.

O’Hare, W. P., & Gutierrez, F. (2012). The use of domains in constructing a compehensive composite index of child well-being. Child Indicators Research, 5, 609–629.

Terry, T., & Huebner, E. S. (1995). The relationship between self-concept and life satisfaction in children. Social Indicators Research, 35, 39–52.

Thomas, W. I., & Thomas, D. S. (1928). The child in America: Behavior problems and programs. New York: Knopf.

Tomyn, A. J., & Cummins, R. A. (2011). The subjective wellbeing of high-school students: validating the personal wellbeing index—school children. Social Indicators Research, 101, 405–418. doi:10.1007/s11205-010-9668-6.

Vandivere, S., & McPhee, C. (2008). Methods for tabulation indices of child well-being and context: an illustration and comnaprion performance in 13 American States. Child Indicators Research, 1, 251–290.

Acknowledgments

Data collection has been supported and developed by UNICEF-Spain. Thanks are due to Gabriel González-Bueno Uribe and to Maria von Bredow, from UNICEF-Spain, and to Irma Bertran, Carme Montserrat and Dolors Navarro for his cooperation in this task; and also to Barney Griffiths for the editing of the English text.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Casas, F., Bello, A., González, M. et al. Children’s Subjective Well-Being Measured Using a Composite Index: What Impacts Spanish First-Year Secondary Education Students’ Subjective Well-Being?. Child Ind Res 6, 433–460 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-013-9182-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-013-9182-x