Abstract

In recent years there has been growing interest in composite indicators as an efficient tool of analysis and a method of prioritizing policies. This paper presents a composite index of intermediary determinants of child health using a multivariate statistical approach. The index shows how specific determinants of child health vary across Colombian departments (administrative subdivisions). We used data collected from the 2010 Colombian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) for 32 departments and the capital city, Bogotá. Adapting the conceptual framework of Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), five dimensions related to child health are represented in the index: material circumstances, behavioural factors, psychosocial factors, biological factors and the health system. In order to generate the weight of the variables, and taking into account the discrete nature of the data, principal component analysis (PCA) using polychoric correlations was employed in constructing the index. From this method five principal components were selected. The index was estimated using a weighted average of the retained components. A hierarchical cluster analysis was also carried out. The results show that the biggest differences in intermediary determinants of child health are associated with health care before and during delivery. According to child health conditions, the departments grouped differently when compared to the traditional classification by Colombian geographical regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years there has been a growing interest in measuring and quantifying well-being of children and its main determining factors through the construction of child well-being indicators (Ben-Arieh 2000, 2008a, b). Several international studies, mainly on developed countries, confirm this interest. It is worth highlighting the research of the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre (2007, 2010) for industrialized countries, the studies by Bradshaw et al. (2007) and Bradshaw and Richardson (2009) for European countries, the annual reports from the KIDS COUNT Data Book by the Annie E. Casey Foundation (2010) and the study by Land et al. (2001) for the United States, and recently, the research on countries located on the Pacific Rim by Lau and Bradshaw (2010). All of these studies built composite indices that sought to capture multiple dimensions that affect children’s well-being, from material well-being, health and education to the perspectives children have of their lives and living conditions. In this study, we focus on one of the dimensions of child well-being: early childhood health.

It is widely accepted that the first years of life are critical in child development. The vast majority of aspects related to child health are determined in the antenatal, delivery and perinatal period (Rigby and Köhler 2002). Child health begins at conception, with antenatal care followed by delivery conditions. After birth, child health is determined by, among other things, adequate nutrition, a healthy environment and access to health services. Child health is a basic indicator of child well-being and is closely related to poverty and the ability to afford health-related services (Spencer 2000). Through the analysis of child health it is possible to identify deficit situations concerning access to and the provision of key health facilities. These deficits pose great challenges for public policy and dealing with them points out the priority that childhood well-being represents in the social and economic agendas of nations.

Against this background, and with the aim of obtaining a better understanding of the differences, determinants and consequences of health inequities, the Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH) was set up in 2005 by the World Health Organization (WHO). The CSDH conceptual framework (see Fig. 1) highlights the importance for policy-making of the distinctions between the social factors that influence health and the social processes that determine their unequal distribution, giving special attention to the context (Solar and Irwin 2010).

Conceptual framework of social determinants of childhood health inequities. Source: Adapted from Solar and Irwin (2010)

The framework includes two key components: structural determinants and intermediary determinants, of health inequities and well-being. The framework shows how the causes of health inequities are rooted in the socio-economic and political context, which gives rise to a set of socioeconomic positions, whereby societies are stratified according to income, education, occupation, gender, race/ethnicity and other factors. These socioeconomic positions in turn have an indirect effect on health status; they operate through a set of specific determinants (intermediary determinants) of health to shape health inequities. The main intermediary determinants are: material circumstances, behavioural factors, biological factors, psychosocial factors and the health system. Material circumstances are related to living and working conditions, food availability, etc. The behavioural factors category is associated with differences in lifestyle, such as tobacco and alcohol consumption, nutritional habits and physical activity. Biological factors include genetic factors, as well as age and gender distribution. Psychosocial circumstances are linked to stressful events experienced in life. Finally, the model includes the health system itself as a social determinant of health (Solar and Irwin 2010).

Most of the studies focus on only one determinant, with no relation to other intermediary factors (Solar and Irwin 2010). However, although we recognize the importance and causal priority of the structural determinants, here we focus on intermediary determinants. These are the most immediate mechanisms through which socioeconomic position operates on child health inequities and their identification may therefore contribute to determining intervention policies at this level.

As recently stated by UNICEF (2009), it has become increasingly evident that the deprivation of children’s rights to survival and development is particularly concentrated in certain continents, regions and countries. Within nations there are also remarkable disparities in the implementation of children’s rights based on circumstances such as geographic location.

There exist a vast evidence of the association between where children live and their health (Marmot et al. 2008). The causal pathways by which the place where people live—communities, neighbourhoods or areas—influences health outcomes and shapes health inequities have been comprehensively discussed in recent literature (Bernard et al. 2007; Cummins et al. 2005, 2007; Diez Roux 2001; Macintyre et al. 2002; Sampson 2008). Place of birth can have considerable influence on a child’s growth, development and survival. It is clear that life chances may be very different depending on whether a child is born, for example, in Sweden or in an African country, but even within countries, these differences in life chances persist between social groups.

This study uses Colombia as context of empirical enquiry. This is an upper-middle income country, heterogeneous both in its geography and in the level of socioeconomic development among regions. The country is divided into 32 departmentsFootnote 1 and one capital district (Bogotá), which is treated as a department. Convergence among Colombian departments and the care allocated to early childhood are two of the priorities of the Colombian government’s strategy included in the National Development Plan 2010–2014. The country has shown significant progress in child health: for example, in the last 5 years, the under-five mortality rate has fallen from 24 to 19 deaths per 1,000 live births, births attended by a doctor have increased by 5 percentage points to 93 % and immunization coverage rates have reached 84 %. However, there are still large differences between departments as well as between urban and rural areas. These differences are reflected in the nutrition indicators for the north coast area, for instance, where the malnutrition rate is four times the national average (Profamilia 2005).

The priority given to childhood issues in Colombia is reflected in the level of official recognition of children’s rights and a consequent improvement in living conditions. The regulatory interest is clearly wide-ranging: examples include the ratification of the CRC in 1991 and the Childhood and Adolescence Code—Act 1098 in 2006 and Act 1295 in 2009—whose target is children under 6 years old and pregnant women from lower socioeconomic levels. The guidelines of Colombian public policy in favour of childhood are also reflected in the document CONPES 109 (DNP 2007) and the National Plan on Children and Adolescence 2009–2019 (MPS 2009). Nevertheless, it is important to monitor how far this interest actually brings about real improvements in well-being for children.

In this study we adapt the conceptual framework of the CSDH to the context of child health and focus on one of the dimensions of child well-being, through the construction of a composite index of intermediary determinants of early childhood health. Composite indicators have proven to be an efficient tool for analysing and formulating public policies, as well as for bench-marking country performances (Saltelli 2007). They are useful tools for simplifying complex or multidimensional phenomena and for making it easier to measure, visualize, monitor and compare trends in several distinct indicators over time and/or across geographic regions (Michalos et al. 2006). However, they may send misleading messages in terms of policy-making if they are not constructed correctly or if they are misinterpreted (OECD 2008).

Some of the most significant limitations in the construction of composite indicators are related to criteria selection and the number of variables included, the well-being dimension that a variable represents, the weighting and aggregation of the variables and the use of different data sources (Hagerty and Land 2007; Moore 1997). Similarly, the aim and interpretation of the index are also subject to discussion (Moore et al. 2003).

Nevertheless, despite the above limitations, composite indicators are an important tool for public policy because they allow us to evaluate how far the policy interest expressed in legislation is reflected in better living conditions for children. They do not necessarily provide an assessment of the results achieved, but they can reflect gaps and deficiencies and make it easier to understand complex phenomena such as child health.

Taking this on board, the aims of this study are: 1) to develop a composite indicator based on intermediary determinants of child health and 2) to utilise this indicator to describe the variability in child health across Colombian departments. Particularly, our Intermediary Determinants of Early Childhood Health Index (IDECHI) focus on answering the following questions: i) Which intermediary determinants are most related to child health according to the index constructed? Additionally, having calculated the index: ii) How do specific determinants of child health vary across Colombian departments and urban/rural areas? and iii) How do departments cluster based on the health of their children according to the index scores?

Analysis by department and type of place of residence above national average not only allows us to analyse territorial disparities in key areas for child development, but also leads to differential strategies in order to reduce place-based inequalities (Coulton and Fischer 2010; Coulton et al. 2009).

2 Methods

With the aim of constructing a composite index of child health, three multivariate statistical methods were used to generate the weights of the variables. Adopting a statistical approach is another way of selecting and aggregating variables without a priori assumptions in the weighting scheme (Lockwood 2004; Njong and Ningaye 2008). Given the discrete nature of the data, we employed three techniques of dimensionality reduction of the data matrix: principal component analysis (PCA) using binary variables; PCA using polychoric correlations (polychoric PCA); and metric multidimensional scaling (MDS). The results of these techniques revealed polychoric PCA to be the method which explains a greater percentage of variance with a lower number of components.

One of the most widely used multivariate techniques in composite indexing is principal component analysis (PCA). The PCA was originally conceived by Pearson (1901) and further developed by Hotelling (1933). PCA is a multivariate statistical technique of dimensionality reduction, which allows a set of k original correlated variables \( X=\left\{ {X_1, {X_2}, \ldots, {X_k}} \right\} \) to be transformed into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components \( PC=\left\{ {P{C_1},P{C_2}, \ldots, P{C_k}} \right\} \). Each component is independent and is a linear weighted combination of the original variables. The first principal component explains the largest proportion of the total variance; the second is orthogonal to the first, with maximal remaining variance, and so on.

Kolenikov and Angeles (2009) have recently described a technique to incorporate categorical variables into PCA using polychoric correlations. They conclude that the proportion of explained variance estimated using this method is more accurate than that generated by other methods. Therefore, if the proportion of explained variance is important to the analysis, polychoric PCA should be used.

The polychoric correlations can be seen as a Pearson’s correlation for ordinal variables. In calculating the polychoric correlation between two ordinal variables X and Y it is assumed that these two variables are the result of categorizing two latent variables x and y with standard univariate normal distribution, and that those two unobserved variables follow a standard bivariate normal distribution with correlation ρ (Olsson 1979). The estimate of that correlation is the polychoric correlation.

For example, in our application the variables “breast” (Months of breastfeeding) and “play” (Frequency played with child last week) are categorical variables with 3 and 4 ordinal categories, respectively. To obtain polychoric correlations, it was assumed that these categorical variables have been obtained by defining 3 and 4 value ranges in two continuous variables, respectively. The aim is to estimate the correlation between these two continuous variables. However, if such variables are known, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient could be used. Note that as with other correlation coefficients (e.g. Pearson), when x = y, the polychoric correlation is 1.

Finally, having obtained the polychoric correlations among pairwise of variables x and y, the correlation matrix is constructed. The PCA is then performed in the usual way. We used the STATA (version 12) commands “polychoric” and “polychoricpca” to estimate the polychoric correlations and perform the PCA.

In addition to this, a hierarchical cluster analysis was carried out based on the selected principal components. In order to group departments together according to the similarity between the values of estimated principal components, the average of the principal component scores of the individuals within each department was calculated. We used a hierarchical agglomerative linkage method, which considers that at the beginning, each department is a group, and in the later stages, the departments are linked using a criterion of similarity between them. A known criterion of hierarchical agglomerative linkage is Ward’s method. This method forms clusters by maximizing within-cluster homogeneity, i.e. minimizing the variance within the formed groups at each stage (Timm 2002). The hierarchical cluster was estimated by the “PROC CLUSTER” procedure of the software SAS (version 9.2).

3 Data

The data used in the analysis were obtained from the Colombian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) conducted in 2010. This survey has been carried out in Colombia by Profamilia every 5 years since 1990. It is a nationally representative survey and covers the urban and rural areas of six regions (Caribbean, Eastern, Bogotá, Central, Pacific, and Amazon and Orinoco) and 33 departments.

DHS data included 17,756 children aged between 0 and 60 months. We selected the variables according to both their relevance to the study and the availability of data. We included a set of 15 variables related to children and their families as proxy measures of the five dimensions included in the intermediary determinants of health, according to the CSDH conceptual framework. It is important to consider that the data on antenatal care, delivery conditions and postpartum care was collected only for the last child born alive, which implied a reduction in the sample size (n = 14,296). For all variables included in the study, values of “don’t know” (1,260) or “missing” (317) were excluded. Thus, our final sample comprised 12,719 children who were alive at the time of the interview and for whom we had complete information.

Having obtained the sample, the weights were corrected so that they added up to the final sample size (12,719). To verify that our sample was still representative by departments, we compared the relative frequencies by department, in both the full sample (17,756) and the final sample. We observed that the order of departments based on the relative frequencies was the same in both samples. Furthermore, the differences between both relative frequencies were compared and the greatest difference between them was found to be 0.005.

3.1 Variables Included in the Analysis

The variables included in the index are defined in Table 1. As indicators of material circumstances, we included as a proxy for the living conditions whether the child lives in overcrowded housing and whether the child is underweight (defined as weight-for-age below—2 standard deviations). Underweight or overall under-nutrition may be the result of both chronic and acute malnutrition (Fotso and Kuate-Defo 2006), and therefore can reflect lack of adequate food or poor sanitary conditions and socioeconomic circumstances.

As a proxy for biological factors, we included three dummy variables for recent illnesses: whether the child had fever, cough or diarrhoea in the 2 weeks preceding the interview. Apart from reflecting the current health status of the child, recent illnesses can reflect children’s living conditions, since they reflect a lack of safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene.

Given that parental behaviour and psychosocial factors can be hard to operationalize and measure, we grouped together a set of variables representing nutritional habits, parenting style and stressful events that can influence a child’s development, as part of the single category termed behavioural and psychosocial factors. As a measure of nutritional habits we included months of breastfeeding. Breastfeeding reduces infant mortality and has benefits for child health in both the short term and the long term. The WHO recommends that infants should be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months with continued breastfeeding for up to 2 years or longer. This variable is measured by duration in months and has three categories: never breastfed, up to 2 years and more than 2 years.

One of the aspects that characterises parenting style is parent’s involvement. To measure this aspect, the frequency with which mother played with the child and the frequency of child’s physical activity were included. Play has a decisive role in the child’s development and is linked to secure attachment with caregivers and relationships with other children (Irwin et al. 2007). It is well known that physical activity has a positive effect on child health (Boreham and Riddoch 2001). Sixty minutes daily at least twice a week are recommended (Strong et al. 2005).

Psychosocial factors include psychosocial stressors, as well as stressful living circumstances and relationships. Physical punishment, despite being a practice socially acceptable as a way to discipline children in many countries (Deater-Deckard et al. 2003; Gershoff 2002; Graziano and Namaste 1990), can be a stressful life event that may affect the child’s health. In this category we included whether the mother physically punished children with spanking, pushing, depriving them of food, hitting with objects, giving them inappropriate work to do or throwing water at them.

Finally, as indicators of maternal and child care and the use and access to the health system we took into account antenatal visits, whether the mother received a tetanus toxoid injection during pregnancy, the person who attended the delivery (doctor or others) and the place of delivery (health institution or others). As an indicator of antenatal care we included the number of antenatal visits during pregnancy. It is estimated that at least four visits during pregnancy improves a range of health outcomes for women and children (WHO 2005). This variable is therefore categorized into no antenatal visits, one to three visits and four or more visits. In addition to this, a child’s access to health system and their immunization were also included. The scope of immunization services and the quality of preventive care provided by health services to children under the age of five are reflected in the coverage of specific vaccines. We included data on whether or not the child had received the third dose of polio vaccine.

3.2 Descriptive Statistics

All the descriptive and statistical analyses were corrected by the STATA command “svy”, which takes into account the survey design. The sample proportions by region of some categories of the variables included in the analysis are shown in the Appendix. The selected categories for each variable are in agreement with those necessary for a child to enjoy good health during childhood. The data show some notable facts, which underline the importance of the analysis by departments rather than by region or country.

For instance, at the regional level, Bogotá has the best performance in child health in the majority of categories; however, it is the region with the lowest proportion of third doses of polio and time spent on children’s physical activity. On the other hand, Amazon and Orinoco are the regions with the highest number of underweight children, children with diarrhoea, mothers without tetanus injections, physically-abused children, and the poorest health systems.

Nevertheless, as stated above, the results by regions should be treated with caution as they may mask substantial differences among departmental conditions. A case in point is the Pacific region, where the departments of Valle and Chocó, in spite of their geographical proximity, have quite different socioeconomic levels. While in Valle, roughly 96 % of the deliveries are attended by a physician in a health institution, in Chocó these indicators only reach 70 %. Differences are also observed in terms of health infrastructure and access, despite almost all children having health insurance, there are departments where deliveries attended in a health institution only reach 72 %.

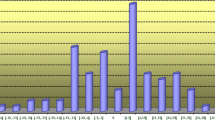

The number of antenatal visits and crowded housing are the variables with the greatest contrast among departments. While 95 % of mothers attended 4 or more check-ups during pregnancy and 87 % of housing has less than three persons per room in Quindío, in Vaupés these figures were 55 % and 52 %, respectively.

It is worth mentioning the case of Chocó. This department exhibits lower rates in almost all health indicators, but the percentage of mothers who breastfed their children up to 2 years is the highest (97 %), which may be associated with economic restraints in acquiring mother’s milk supplements.

4 Results

4.1 Construction, Components and Dimensions Represented by the Index of Intermediary Determinants of Early Childhood Health—IDECHI–

A widely used criterion for selecting the number of retained principal components is that proposed by Kaiser (Kaiser 1960) which suggests retaining components with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Based on this criterion and analyzing the minimal number of principal components which incorporate the 15 original variables included in the IDECHI, we identified five components: PC1, PC2, PC3, PC4 and PC5. These components explain 60 % of the total variance. Also, to maximize the correlation between original variables and principal components, the latter have been rotated using VARIMAX criteria (Kaiser 1958).

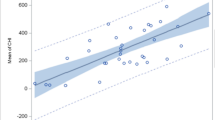

Having obtained the principal components, two indices were estimated. The first index was calculated giving equal weights to each component. The second one was estimated as a weighted average of the retained components, taking into account the proportion of explained variance by each dimension. The weightings were calculated dividing each eigenvalue into the sum of the eigenvalues retained. Nevertheless, when we used equal weights as the method for estimating the index, the departments’ positions did not change significantly. In fact, the positions of the departments at the top and bottom of the ranking remained practically the same with both methods. In this paper we only show the results of the weighted indicator.

The indicator is centred on zero; more positive scores, therefore, indicate departments that have better child health conditions, whereas those with more negative scores have a worse performance. The indicator allows us to identify the health dimensions in which a department presents deficits with respect to the rest of the country.

The variables represented by each component and the rotated matrix of correlations between PC and original categorical variables are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Within each PC, the variables with the greatest correlation were selected.

The results show that the first component, PC1, is related to maternal care and use of health facilities. This component includes the person who attended the delivery, the place of the delivery and the antenatal care. Variables that reflect biological factors, such as recent illnesses, are grouped together in the second component, PC2. In the third component, PC3, factors related to parenting style such as playing, physical exercise and punishment are represented. The fourth component, PC4, is associated with material circumstances and encompasses household living conditions and nutritional status. It is important to bear in mind that although the play variable has the strongest correlation with the third component, it is also strongly associated with PC4. Finally, child health insurance and immunization are represented in the fifth component, PC5. The components are interpreted positively, i.e. the higher the score, the better the child’s health.

Table 3 indicates that not having appropriate antenatal care, giving birth at home and without help from a doctor, are the variables that most differentiate child health. As we expected, mothers not having received antenatal care negatively affects child health. Moreover, although the correlation is lower, having fewer antenatal visits than recommended has an equally negative impact on child health.

Likewise, breastfeeding for more than 2 years correlates negatively with child health. In conditions of poverty an increase in breastfeeding may mean that it is not possible to supplement the child’s diet with other foods.

The magnitude and sign of the correlations associated with the play variable suggest that participating in this type of activity—as opposed to not doing it—positively affects child health. Furthermore, the more frequent the activity, the stronger the relationship to child health. At the same time, we observe that this variable is closely related to household material circumstances (PC4). This may indicate that the play variable could be connected to parenting style but, at the same time, is positively linked to parental socioeconomic status, as demonstrated in some studies (Guryan et al. 2008).

The results show the positive effect of physical activity on child health. However, it would seem that performing this activity once a week is not sufficient to influence child health in a positive way.

The correlation matrix also suggests that physical abuse is linked to parenting style. Nevertheless, the relatively low correlation of this variable may show the ambiguity of its effect on child health. On the one hand, we might expect that given its physical and psychological consequences, physical abuse would have a negative effect on child health. On the other hand, however, punishment as a way of disciplining a child would reflect stricter parents and therefore would have a positive influence on child health (Deater-Deckard et al. 2003; Gershoff 2002).

4.2 Colombian Departments’ Heterogeneity in Intermediary Determinants of Early Childhood Health

The indicator of intermediary determinants of early childhood health (IDECHI) allows departments to be ranked and differences in child health across Colombian regions to be analysed. With the aim of showing the heterogeneity of the distribution of the departments among components, ranking by principal components is presented in Table 4. The departments best/worst ranked for each component are: Atlántico/Vaupés (maternal care and use of health facilities), Boyacá/Amazonas (biological factors), Antioquia/Chocó (behavioural and psychosocial factors), Quindío/Vaupés (material circumstances) and Antioquia/Guajira (child care and access to health system).

The analysis of the IDECHI by components shows heterogeneity in the health performance of the departments. There is no one department that ranks top in all five components. Bogotá, for instance, which is in first position in the global indicator, is ranked 19 out of 33 for child health insurance and immunization. Boyacá and Cundinamarca, in second and third place, are ranked 10 and 15 respectively for health at birth. In the case of the lowest ranking departments, we note that Vaupés is ranked 19 for recent illnesses but is in the lowest positions in the other health dimensions.

The IDECHI ranking of Colombian departments in 2010 is shown in Table 5. The departments are organized by region and the results are presented for urban and rural areas. The results indicate that Vaupés, Chocó, Amazonas, Vichada and Guajira are ranked in the lowest positions, while Bogotá, Boyacá, Cundinamarca, Quindío and Valle are at the top of the ranking. This order remains roughly the same for rural areas. In urban areas, the bottom of the ranking is invariable but the top end shows significant changes. In this particular case, the departments with better performance are: Antioquia, Bogotá, Cundinamarca, Huila and Nariño.

4.3 Clustering of Colombian Departments According to the IDECHI

From the retained principal components, a hierarchical cluster analysis was carried out. The cluster analyses allow us to generate an alternative classification of departments, taking into account the characteristics of child health rather than geographical location. The departments by cluster are shown in Table 6 and Map 1.

The results indicate that cluster 1 is formed by 13 departments that perform best in all components. Cluster 3 is formed by five departments with a good performance in the first four components. These clusters group those departments that are in the top 5 of the indicator. These are departments located in the centre of the country.

Clusters 2 and 4 show a heterogeneous performance in child health. Cluster 2, made up of five departments, performs better in health at birth and access to health care, whereas it has deficiencies in current health status, parenting style and living conditions. Cluster 4, formed by five departments, is below the average in all components with the exception of the first. Eight of the ten departments that form these clusters are located in the north of the country.

The departments in cluster 5 are located in the peripheral region and show a poor performance in all dimensions of intermediary determinants of child health. The four departments in this group rank lowest in the IDECHI.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we have presented a description of intermediary determinants of early childhood health in Colombia by department and place of residence (urban/rural) through the construction of a composite indicator of child health. We have used data from the 2010 Colombian Demographic Health Survey (DHS), taking into account several dimensions of children’s health throughout their first 5 years of life, including antenatal health. The index has been computed using polychoric PCA. From this method five principal components were selected. The index grouped together variables related to intermediary factors of child health, such as the use of health facilities at birth, recent illnesses, parenting style, living conditions and nutritional habits, and more general access to health services.

The analysis of the IDECHI indicated that department performance varies according to component. A department can perform very well in one dimension but at the same time may rank in lowest position in another child health dimension. With regard to place of residence, the results show that rural areas have more child health needs compared to urban areas. Furthermore, according to the evidence of economic and social indicators in Colombia, we find a positive association between performance in intermediary determinants of child health, socioeconomic conditions and the health infrastructure of the departments. Although this issue is not dealt with in depth in this paper, some conclusions can be drawn. The departments with the best child health conditions are those where the economic activity of the country is concentrated and poverty rates are lower. The departments ranking at the bottom have the highest levels of poverty. The results suggest that the regional disparities in child health may be associated with differences in parental characteristics, household conditions and economic development levels, which highlight the importance of context in the study of child health in Colombia. In this vein, our indicator can provide relevant information and may be a useful tool for designing public programmes and allocating resources in favour of children.

On the other hand, the results of the hierarchical cluster show that departments that perform well in most of the specific determinants of early childhood health are located in the centre of the country. These are the departments with the greatest economic competitiveness. In contrast, those departments where intermediary determinants of child health perform worst are located in the Amazon and Orinoco, Pacific and Atlantic regions, which together are known as the peripheral region. This region is characterized by having per capita GDP levels well below the national average, little State presence, a hostile environment and a large proportion of the ethnic minorities in the region (Galvis and Meisel 2010; Meisel 2007). For these reasons, in this region priority should be given to designing policies aimed mainly at the health care of mothers and children at birth, as well as the development of programmes that aim to improve departmental equity in access to key goods and facilities for child well-being.

To sum up, in answer to our research questions, we found that: i) intermediary determinants that correlate strongest with child health are those associated with health before and during delivery, ii) department performance in intermediary determinants of child health varies significantly by dimension. With regard to place of residence, urban areas have advantages in intermediary determinants of child health compared to rural areas, and iii) in relation to their child health, departments grouped differently to the geographical regions traditionally established in regional studies and in other surveys in the country, such as Quality Life Survey.

This study attempts to represent, in one single index, intermediary determinants of child health. The composite indicators approach may contribute towards a better understanding and visualization of the differences in intermediary determinants of child health, to the extent that it enables us to analyse the phenomenon, both in an overall perspective and in exploring its dimensions. Furthermore, the index enables us to analyse relative differences in child health among Colombian departments, which can send important policy messages which could contribute to the reduction of territorial inequities.

However, there are obvious limitations in this study. Firstly, the exclusion of the psychosocial factors assessed here from previous Colombian DHS, and the lack of recent DHS or unavailability of such data from other Latin American countries, makes it impossible to compare our index with others. Secondly, it is worth noting that there are also other intermediary factors that are not accounted for in this study due to the lack of available data, such as, for instance, socially accepted behaviours and practices that can affect child environment, as well as levels violence and safety conditions where children live. Additionally, barriers to accessing health facilities and nurseries can be important intermediary factors of child health.

Finally, it should be noted that although the intermediary determinants presented here are important pathways and mechanisms through which social determinants influence child health, clearly they are not the only ones. Therefore, further research is required in the study of child health inequities. The analysis should be complemented by identifying structural determinants that give us a more complete view of child health and inequities in well-being. Despite this, the methodological approach employed here—through the empirical construction of a weighted composite index—makes it easier to understand the relative status of intermediary determinants of child health in Colombia.

The composite indicators approach and the weighting procedure used in the construction of the index, provide an opportunity to identify key intermediary factors of child health and their relative importance. Furthermore, these kinds of indicators may help identify potential intervention strategies for more downstream determinants of child health. It highlights the relevance these factors have in terms of public policy, to the extent that they can be modified easily, for instance, through child care programmes.

Nevertheless, further work is necessary to improve the index, its robustness and the validity of the results over time. Against this backdrop, it is important that in future research other countries are included in the analysis, as well as the identification of other dimensions that impact on child development. We hope that this study helps to draw the attention of policy makers to this vulnerable population and that it may be used as a criterion for the allocation of public funds.

Notes

Departments are subdivided into municipalities.

References

Annie E Casey Foundation. (2010). KIDS COUNT data book: State profiles of child well-being (p. 56). Baltimore: The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Ben-Arieh, A. (2000). Beyond welfare: measuring and monitoring the state of children—new trends and domains. Social Indicators Research, 52, 235–257.

Ben-Arieh, A. (2008a). Indicators and Indices of Children’s Well-being: towards a more policy-oriented perspective. European Journal of Education, 43, 37–50.

Ben-Arieh, A. (2008b). The child indicators movement: past, present, and future. Child Indicators Research, 1(1), 3–16.

Bernard, P., Charafeddine, R., Frohlich, K. L., Daniel, M., et al. (2007). Health inequalities and place: a theoretical conception of neighbourhood. Social science and medicine, 65(9), 1839–1852.

Boreham, C., & Riddoch, C. (2001). The physical activity, fitness and health of children. Journal of sports sciences, 19(12), 915–29.

Bradshaw, J., Hoelscher, P., & Richardson, D. (2007). An index of child well-being in the European Union. Social Indicators Research, 80(1), 133–177.

Bradshaw, J., & Richardson, D. (2009). An index of child well-being in Europe. Child Indicators Research, 2(3), 319–351.

Coulton, C. J., & Fischer, R. L. (2010). Using early childhood wellbeing indicators to influence local policy and services. In S. B. Kamerman, S. Phipps, & A. Ben-Arieh (Eds.), From child welfare to child well-being (Vol. 1, pp. 101–116). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Coulton, C. J., Korbin, J. E., & McDonell, J. (2009). Editorial: indicators of child well-being in the context of small areas. Child Indicators Research, 2(2), 109–110.

Cummins, S., Curtis, S., Diez-Roux, A. V., & Macintyre, S. (2007). Understanding and representing “place” in health research: a relational approach. Social science & medicine, 65(9), 1825–38.

Cummins, S., Macintyre, S., Davidson, S., & Ellaway, A. (2005). Measuring neighbourhood social and material context: generation and interpretation of ecological data from routine and non-routine sources. Health & Place, 11(3), 249–60.

DNP. (2007). Conpes Social 109: Política pública nacional de primera infancia: Colombia por la primera infancia (p. 39). Bogotá: Departamento Nacional de Planeación.

Deater-deckard, K., Lansford, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2003). The development of attitudes about physical punishment: an 8-year longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(3), 351–360.

Diez Roux, A. V. (2001). Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American journal of public health, 91(11), 1783–9.

Fotso, J.-C., & Kuate-Defo, B. (2006). Household and community socioeconomic influences on early childhood malnutrition in Africa. Journal of biosocial science, 38(3), 289–313.

Galvis, L. A., & Meisel, A. (2010). Persistencia de las desigualdades regionales en Colombia: Un análisis espacial (Working paper No. 120). Retrieved from Banco de la República Centro de Estudios Económicos Regionales (CEER) website: http://www.banrep.gov.co/documentos/publicaciones/regional/documentos/DTSER-120.pdf

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579.

Graziano, A., & Namaste, K. (1990). Parental use of physical force in child discipline: a survey o 679 college students. Journal of interpersonal violence, 5(4), 449–463.

Guryan, J., Hurst, E., & Kearney, M. (2008). Parental education and parental time with children. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 23–46.

Hagerty, M. R., & Land, K. C. (2007). Constructing summary indices of quality of life: a model for the effect of heterogeneous importance weights. Sociological Methods & Research, 35(4).

Hotelling, H. (1933). Analysis of a complex of statistical variables into principal components. Journal of Educational Psychology, 24, 417–441.

Irwin, L., Siddiqi, A., & Clyde, H. (2007). Desarrollo de la Primera Infancia: Un Potente Ecualizador. Resource document World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/publications/early_child_dev_ecdkn_es.pdf. Accessed 26 Jul 2011.

Kaiser, H. F. (1958). The varimax criterion for analytic rotation in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 23(3), 187–200.

Kaiser, H. F. (1960). The application of electronic to factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20, 141–151.

Kolenikov, S., & Angeles, G. (2009). Socioeconomic status measurement with discrete proxy variables: is principal component analysis a reliable answer? Review of Income and Wealth, 55(1), 128–165.

Land, K. C., Lamb, V. L., & Mustillo, S. K. (2001). Child and youth well-being in the United States 1975–1998: some findings from a new index. Social Indicators Research, 56, 241–320.

Lau, M., & Bradshaw, J. (2010). Child Well-being in the Pacific Rim. Child Indicators Research, 3(3), 367–383.

Lockwood, B. (2004). How robust is the Kearney/Foreign policy globalisation index? The World Economy, 27(4), 507–523.

MPS. (2009). Plan Nacional para la Niñez y la Adolescencia (p. 94). Bogotá: Ministerio de Protección Social.

Macintyre, S., Ellaway, A., & Cummins, S. (2002). Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Social Science & Medicine, 55(1), 125–139.

Marmot, M., Friel, S., Bell, R., Houweling, T. A. J., & Taylor, S. (2008). Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The Lancet, 372(9650), 1661–1669.

Meisel, A. (2007). La Guajira y el mito de las regalias redentoras. (Working paper No. 86). Retrieved from Banco de la República Centro de Estudios Económicos Regionales (CEER) website: http://www.banrep.gov.co/documentos/publicaciones/regional/documentos/DTSER-86.pdf.

Michalos, A. C., Sharpe, A., & Muhajarine, N. (2006). An Approach to a Canadian Index of Wellbeing. Resource document Centre of Expertise on Culture and communities. http://cultureandcommunities.ca/cecc/downloads/indicators-2006/Michalos-Sharpe-Muhajarine-Approach-CdnIndex-Wellbeing.pdf. Accessed 22 Sep 2010.

Moore, K. A. (1997). Criteria for indicators of child well-being. In R. M. Hauser, B. V. Brown, & W. R. Prosser (Eds.), Indicators of child well-being (pp. 36–44). New York: Russell Sage.

Moore, K. A., Brown, B. V., & Scarupa, H. J. (2003). The uses (and misuses) of social indicators: Implications for public policy. Resource document Child Trends. http://www.childtrends.org/files/child_trends-2003_02_01_rb_useandmisuse.pdf. Accessed 3 Sep 2010.

Njong, A. M., & Ningaye, P. (2008). Characterizing weights in the measurement of multidimensional poverty: An application of data-driven approaches to Cameroonian data (Working Paper No 21). Retrieved from Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) website: http://www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/OPHI-wp21.pdf.

OECD. (2008). Handbook on constructing composite indicators: Methodology and user guide. Methodology. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Olsson, U. (1979). Maximum likelihood estimation of the polychoric correlation coeficient. Psychometrika, 44(4), 443–460.

Pearson, K. (1901). On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Philosophical Magazine, 2, 559–572.

Profamilia (2005). Salud Sexual y Reproductiva en Colombia: Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud ENDS 2005. Resource Document Asociación Probienestar de la Familia Colombiana. http://www.profamilia.org.co/encuestas/Profamilia/Profamilia/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=82&Itemid=526. Accessed 27 Oct 2009.

Rigby, E. M., & Köhler, L. (2002). Child Health Indicators of Life and Development (CHILD) Report to the European Commission.

Saltelli, A. (2007). Composite indicators between analysis and advocacy. Social Indicators Research, 81(1), 65–77. doi:10.1007/s11205-006-0024-9.

Sampson, R. J. (2008). Moving to inequality: neighborhood effects and experiments meet social structure. American Journal of Sociology, 114(1), 189–231.

Solar, O., & Irwin, A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice).

Spencer, N. (2000). Poverty and child health. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press.

Strong, W. B., Malina, R. M., Blimkie, C. J. R., Daniels, S. R., et al. (2005). Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. The Journal of pediatrics, 146(6), 732–737.

Timm, N. H. (2002). Applied multivariate analysis. New York: Springer.

UNICEF (2007). Child poverty in perspective: An overview of child well-being in rich countries: A comprehensive assessment of the lives and well-being of children and adolescents in the economically advanced nations. Innocenti Report Card 7. Resource Document United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Innocenti Research Centre. http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc7_eng.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2011.

UNICEF (2009). The State of the World’s children Celebrating 20 Years of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Resource Document United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). http://www.unicef.org/rightsite/sowc/pdfs/SOWC_Spec%20Ed_CRC_Main%20Report_EN_090409.pdf. Accessed 15 Sep 2010.

UNICEF (2010). The children left behind: A league table of inequality in child well-being in the world’s rich countries. Innocenti Report Card 9. Resource Document United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Innocenti Research Centre. http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc9_eng.pdf. Accessed 4 Feb 2011.

WHO (2005). The World Health Report 2005: make every mother and child count. Resource Document World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/whr/2005/whr2005_en.pdf. Accessed 22 Jun 2010.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support by the Spanish Ministry of Science FEDER Grants 21787-C03-01 and ECO2008-01223. Ana Maria Osorio also has been supported by the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Cali-Colombia. The authors are extremely grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osorio, A.M., Bolancé, C. & Alcañiz, M. Measuring Intermediary Determinants of Early Childhood Health: A Composite Index Comparing Colombian Departments. Child Ind Res 6, 297–319 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-012-9172-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-012-9172-4