Abstract

Research on resilience helps parents promote health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and mitigate stress associated with raising a child with disabilities. Therefore, understanding how resilience works for parents to inform future interventions and services is important. However, the mutual relations among parental stress, family resilience, and parents’ HRQOL for families of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have not been investigated in the literature. This study examined the associations among these three variables for these families and would benefit the parents as well as their children. A sample of 1003 parents of children with ASD reporting both parents’ HRQOL from a national dataset was included in this study. This dataset surveyed parents who had a child aged 0–17 in the household in the United States. The investigated latent variables were constructed by the items selected from the survey. Results showed that parental HRQOL could be directly affected by parental stress β = − 0.19, p <.001 and family resilience, β = 0.31, p <.001. Parental stress could be directly affected by family resilience, β = − 0.29, p <.001. Parental HRQOL could be indirectly affected by family resilience through parental stress, β = 0.055, SE = 0.013, p <.001, 95% CI = 0.034 to 0.084. In conclusion, family members could rely on and share the burden and responsibility for each other to increase their family resilience, which could assist parents to reduce their parental stress and directly and through the reduction of their parental stress indirectly increase their HRQOL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Care giving is usually demanding and overwhelming for parents of children with disabilities, which could impact their physical and mental health (Iacob et al., 2020). However, when confronting difficulties, some parents show resilience, but some parents have hard time accepting diagnosis of their children’s disabilities (Iacob et al., 2020). Why do some people overcome life risks and stay healthy whereas others yield to stress and adversity? Resilience, which concerns individual variations in response to risk, has become a field for researchers and practitioners to explore (Patterson, 2002). Particularly, this phenomenon has been studied among individuals with disabilities and their family members, because it focuses more on strength and healthy adaptation rather than a deficits orientation (Fong et al., 2021; Urbanowicz et al., 2019; Menezes et al., 2023). Therefore, understanding how resilience works for families of children with disabilities to inform future interventions and services is important.

The early studies that viewed resilience as a trait mainly focused on individual qualities of resilient children, for example, who were autonomous or had high self-esteem (Luthar et al., 2000; Masten, 2007). However, incorporating with the theoretical framework of transactions between the ecological context and the development of children, such as Human Ecology Theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), Family Systems Theory (Turnbull et al., 1984), and Ecological-Transactional Model (Cicchetti & Lynch, 1993), in which various environmental system, including family and its wider social environments and subsystems, interacts with family members over time in affecting human adaptation and development and thus contributes to risk and resilience (Masten & Monn, 2015), researchers in this field have indicated that there are three sets of resilient factors emerged from three different levels of the ecosystem (Luthar et al., 2000). The three sets of resilient factors are: (a) traits of individual family members, such as intelligence, self-esteem; (b) features of their family, such as parenting quality, family cohesion; and (c) characteristics of their wider social environment, such as good health and education services. In addition to treating resilience as a trait, researchers in the field have also advocated to view resilience as a process to better understand “the protective process” for the individuals to be resilient, which means understanding how factors interact with risks relative to positive outcomes (Luthar et al., 2000, p. 3). For instance, three models have been proposed by Garmezy et al. (1984) for understanding different processes that may help the individual family member offset or mitigate the impact of the adversity and obtain better development and adaptation (i.e., the factors may have direct, indirect, and inoculation effects on the outcomes) (Zimmerman & Arunkumar, 1994). In sum, the theoretical frameworks and the empirical studies for resilience have offered several guidelines for researchers and practitioners to explore potentially new avenues for study and application so as to design appropriate services and interventions that better meet individuals’ and families’ needs when facing adversity.

One in 36 children has been identified with ASD in the United States (Maenner et al., 2023). Parents of children with ASD face ongoing challenges. These challenges can influence their various life domains (e.g., health, goals, work, and community involvement; Hsiao, 2016; Johnson et al., 2011; Peer & Hillman, 2014). Therefore, many researchers have investigated factors related to these aspects and identified the ways to help these parents to be resilient. For example, Bekhet et al. (2012) used the main constructs of resilience theory to investigate studies related to resilience in these families. They summarized risk factors (e.g., severity level of ASD and parents’ anger), protective factors (e.g., cognitive appraisal, social support, and religious beliefs and spirituality), indicators of resilience (e.g., optimism, positive family functioning, and sense of coherence), and outcomes of resilience (e.g., better marital quality, less depression, and greater life satisfaction) for interventions to help an adult who had a family member with ASD to be resilient. Peer and Hillman (2014) identified resilient factors for parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities to face parental stress in a systematic review. They summarized social support, optimism, and coping style as main resilience variables for these parents. Iacob et al. (2020) used the meta-analysis method to synthesize multiple research results on resilience factors for caregivers of children with developmental disabilities. They found that coping, perceived health, life satisfaction, and social support were positively related to resilience. Nevertheless, after rigorous examination in the extant literature, it can be found that most studies identified resilient factors that protect parents from stress from an individual level (e.g., coping style, optimism) and a wider social environment level (e.g., social support, professional support) with only a few studies from a family level (e.g., family cohesiveness, family functioning). Most studies used correlation and regression to understand their relationships among these variables. This phenomenon was also observed by Masten (2007) who called it as the first wave of research on resilience. There were only a few studies (e.g., Halstead et al., 2018; Hsiao, 2016) which applied path analysis to understand how resilient factors affect the association between parental stress and parent’s HQOL in families of children with ASD for better understanding the resilience process as proposed by Garmezy et al. (1984). Up to now, the mutual relations among parental stress, family resilience, and parents’ HRQOL for these families have not been yet investigated, especially, in viewing the family resilience as a family level variable in resilience theory to affect this relationship. In addition, Iacob et al. (2020) found that 88.57% of the participants from the 26 studies they included in their analysis were females and asked for more involvement of males as samples in the future resilience research. To address this gap, therefore, the current study investigated the perceptions of both parents of children with ASD to apprehend the interrelations among parental stress, family resilience, and parents’ HRQOL so as to identify the possible paths among these variables for designing intervention or services to better help these families.

Relations between parental stress and HRQOL

Parents of children with ASD usually face many challenges (e.g., children’s behavior, communication, and social problems). These all lead to stress for parents. Parental stress is “defined as parental perceptions of an imbalance between the demands of parenting and available resources” (Hsiao, 2018, p. 201). Many studies indicated that parents of children with ASD had a high level of parental stress (e.g., Cheatham & Fernando, 2022; Hoffman et al., 2009; Meadan et al., 2010; Prata et al., 2019). As such, the factors related to parental stress need to be identified to help these parents reduce their stress.

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) refers to individual physical and mental health status and its impact on their quality of life. It is a helpful indicator of overall health (Yin et al., 2016). Because HRQOL influences the adaption and coping for parents to face the presence of a child with disabilities in families (Hsiao, 2016; Tung et al., 2014), exploring this variable is important for designing support and services and understanding their effectiveness. Parents would be more supportive of their child with ASD, when they have strong HRQOL (Chuang et al., 2014; Feetham, 2011). Nevertheless, these parents tend to report a low level of HRQOL (Khanna et al., 2011). Previous studies showed many factors (e.g., family sense of coherence, parental stress, and child’s performance) affecting HRQOL in parents (e.g., Hsiao, 2016; ten Hoopen et al., 2022). These factors include parental stress. Theoretically, the negative association between parental stress and parents’ HRQOL can derive from the theory of Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Johnson et al., 2011).

Relations of family resilience to parental stress and HRQOL

Family resilience treats family as a functional unit and refers to “the functioning of the family system in dealing with adversity” (Walsh, 2016, p. 616); especially it focuses on the process of family stress, coping, and adaptation to help the whole family unit and all members in face of adversities have positive adaption. Therefore, the specific set of resilience capacities (i.e., the feature of the family), is concerned in this study, especially, as mentioned above, most of the previous studies for families of children with ASD only examine the influences of resilience of individual family members (e.g., caregivers or parents) on the families and their members (Bekhet et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2020). Plumb (2011)’s study was one of the few studies that viewed the family resilience as a family level variable for these families and examined the relationship between this family-level variable with other variables. Results of Plumb’s study found that family resilience could help parents reduce their parental stress. In recent years, a few other studies also revealed the same results as Plumb’s study (Cheatham & Fernando, 2022; Kim et al., 2020).

Additionally, other studies consider family features as a unit and show its influences on parental stress and HRQOL for families of children with ASD. For instance, Johnson et al. (2011) investigated the associations among parenting stress, parental HRQOL, and family functioning for these families. Their study showed that fathers’ physical health and both parents’ mental health were related with family and personal life stress; the association between family and personal life stress and both parents’ mental health could be mediated by the discrepancy scores between expectation and satisfaction in family functioning. Thus, from the theoretical foundations of family resilience and the results of the past studies, we could hypothesize that parental HRQOL could be directly affected by parental stress and family resilience; parental stress could be directly affected by family resilience; parental HRQOL could be indirectly affected by family resilience through parental stress.

Aims of the study

The purpose of this study was to further examine the aforementioned hypothesis. That is, the interrelations among parental stress, family resilience, and HRQOL for families of children with ASD. Specially, parental stress and family resilience were considered relevant to HRQOL. The hypothesized model to indicate the pathways for these variables was shown in Fig. 1.

Method

Data source

The 2018–2019 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) Combined Data Set was used for this cross-sectional study. It was conducted across 2018 and 2019. An invitation mail to complete the survey was sent out to households through a randomly selected method across the United States asking an adult to fill out a screener questionnaire. If the adult/parent who reported a child aged 0–17 in the household was willing to answer a full questionnaire, they could complete it for a randomly selected child either via online or paper. A total of 59,963 surveys were completed with 30,530 in 2018 (43.1% completion rate) and 29,433 in 2019 (42.4% completion rate) (Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative [CAHMI], 2021).

Samples

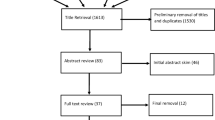

Out of the 59,963 surveys completed, 1,602 (2.67%) respondents indicated that their child had ASD. Because this study was focused on parents’ physical and mental HRQOL, only respondents who reported data on both parents’ (i.e., a two-parent household) HRQOL were included for the analysis. In this survey, a parent is referred to as a biological, adoptive, foster, or step mother or father. This study included 1003 parents of a child with ASD ages 3–17. Of these participating respondents, over two-third of the participants were White (n = 708, 70.59%). About 60% of participants had a college degree or higher. The majority of the primary language spoken in the household is English (n = 948, 94.52%). Of the children with ASD, there were 804 boys (80.16%) and 199 girls (19.84%), aged younger than 6 (121, 12.06%), 6 to 10 (272, 27.11%), 11 to 15 (416, 41.48%), and 16 to 17 (194, 19.34%). More family demographic information is shown in Table 1.

Measures

The investigated latent variables of parental stress, family resilience, and parental HRQOL were constructed by the items selected from the survey.

Parental stress

There were three questions used to measure parental stress in raising a child. An example question for this factor was: “During the past month, how often have you felt angry with [CHILD’S NAME]?”. Participants rated these questions with “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “usually”, and “always”. However, the scale categories of “usually” and “always” for this variable were combined to assign the same scale value by the original data source due to a small number of respondents in these two scale categories (CAHMI, 2021). That is, the variable was coded with usually or always = 4, sometimes = 3, rarely = 2, and never = 1. The more the demands of parenting on the family were, the higher parental stress would be. The current study has Cronbach’s alpha = 0.77.

Family resilience

Family resilience included three questions to measure the qualities essential to resilience during difficult times (CAHMI, 2021). An example question for this factor was: “When your family faces problems, how often are you likely to talk together about what to do?”. Participants rated these questions from “none of the time” to “all of the time”. However, the scale categories of “none of the time” and “some of the time” for this variable were combined to assign the same scale value by the original data source due to a small number of respondents in these two scale categories (CAHMI, 2021). That is, the variable was coded with “some/none of the time”, “most of the time”, and “all of the time” with the numerical values of 3, 2, 1, respectively. The variable was reversely recoded with the numerical values of 1, 2, 3, respectively for the purpose of the current study. Higher scores showed that during difficult times family demonstrates higher qualities of resilience. The current study has Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89.

Parental HRQOL

There were four questions used to measure parental HRQOL. An example question for this factor was: “Would you say that, in general, ([CHILD’S NAME] [MOTHER TYPE]/your physical health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”. Participants rated these questions from “excellent” to “poor”. However, the scale categories of “excellent” and “very good” and the scale categories of “fair” and “poor” were respectively combined to assign the same scale value by the original data source due to a small number of respondents in these scale categories (CAHMI, 2021). That is, the variable was coded with fair or poor = 3, good = 2, and excellent or very good = 1. This variable was reversely recoded with the numerical values of 1, 2, 3, respectively for the purpose of the current study. Higher scores indicated better parental HRQOL. The current study has Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74.

Data analysis

First, the ratio of missing data was examined by the frequency method. All variables had less than seven missing values. Additionally, 20 out of 1003 participants have missing values, which was observed for 1.99% (20/1003) of all data. Thus, the subsequent statistical analyses might not be affected by the missing data (Bennett, 2001). The participants with missing values were deleted.

Second, the measurement and the structural models were tested by the structure equation modeling. The measurement model depicted the factor loadings of the indicators and the correlations for the latent factors of family resilience, parental stress, and HRQOL. The structural model depicted the mutual relations of these three latent factors (see Fig. 1). The indices as shown in Table 2 were used as the criteria for model adequacy (Byrne, 2010; Schumacker & Lomax, 2004). The indirect effect was tested by the bootstrap method.

Results

The measurement model

The indicators and factors of parental HRQOL, family resilience, and parental stress were specified in the measurement model to test their construct validities. After modification, this model had a great fit, χ2/df = 3.760, CFI = 0.979, NFI = 0.972, RMSEA = 0.053, compared with the acceptable values of the fit indices suggested by experts as shown in Table 2 (Byrne, 2010; Schumacker & Lomax, 2004). The item indicators could adequately construct the latent factors (i.e., parental HRQOL, family resilience, and parental stress) based on statistically significant estimates of all factor loadings. Table 3 presents the item indicators with the standardized factor loadings for the latent factors.

The Pearson’s Coefficients were from − 0.276 to 0.366 for these latent variables as shown in Table 4. Family resilience had a positive relationship with parental HRQOL (r =.366). Parental stress had a negative relationship with family resilience (r = −.290) and parental HRQOL (r = −.276). The hypotheses of the relations for these latent variables were supported by the correlations.

The structural model

The hypothesized structural model with the modification indices represented a great model fit, χ2/df = 3.760, CFI = 0.979, NFI = 0.972, RMSEA = 0.053, compared with the acceptable values of the fit indices suggested by experts as shown in Table 1. (Byrne, 2010; Schumacker & Lomax, 2004). In addition, the paths for the hypothesized model were meaningful, as shown in Fig. 2. Parental HRQOL could be directly affected by parental stress β = − 0.19, p <.001 and family resilience, β = 0.31, p <.001. Parental stress could be directly affected by family resilience, β = − 0.29, p <.001. Parental HRQOL could be indirectly affected by family resilience through parental stress, β = 0.055, SE = 0.013, p <.001, 95% CI = 0.034 to 0.084 (based on 1000 bootstrap samples).

Discussion

The interrelations among parental stress, family resilience, and HRQOL were examined for families of children with ASD in this study. The results showed that parental HRQOL could be directly affected by parental stress and family resilience. Parental stress could be directly affected by family resilience. Parental HRQOL could be indirectly affected by family resilience through parental stress.

A lower level of HRQOL was perceived by parents when they had a higher level of parental stress. This finding aligned with the results of several studies conducted before (e.g., Hsiao, 2016; McStay et al., 2014). For instance, parental HRQOL could be predicted by parental stress for parents of children with high-functioning ASD (Lee et al., 2009). The result of this study extended the concept of HRQOL to both parents of children with ASD. In Hsiao’s (2016) study, among a couple of variables that contributed to parental mental HRQOL, parental stress was identified as a major factor related to the mental HRQOL of parents. The result of this current study included physical HRQOL into the parental HRQOL variable. It indicated that parental HRQOL was negatively associated with parental stress. One potential explanation for this result could be that parenting stress is related to the many constraints imposed by the increased role demands on parents on different life domains (e.g., reduced sleep, leisure, social time), which has a negative effect on their HRQOL.

The finding that family resilience could help parents reduce their parental stress echoes the results of some studies conducted before (Cheatham & Fernando, 2022; Plumb, 2011). For example, Oelofsen and Richardson (2006) found that the sense of coherence, which is a feature of family resilience, was related to parental stress for families of children with developmental disabilities. Regarding the relations between parental HRQOL and family resilience, the finding of the current study extends the results of previous literature, which showed that resilience of mothers was associated with their perceived health (e.g., Ruiz-Robledillo et al., 2014). The finding of the current study indicated that when both parents perceived higher levels of family resilience, they tended to have a better HRQOL. The results that family resilience could reduce parental stress and promote parental HRQOL could be that family resilience is grounded in a systemic orientation and derived from individual resilience and effective family functioning. By definition, it is the crucial family processes that could lessen stress and adversity and foster positive adaptation and the well-being of members and families. Finally, the result of the current study that family resilience might promote parental HRQOL through the reduction of parental stress could be explained by Johnson et al.’s (2011) study as mentioned above. The relations among the variables of parental stress, family resilience, and parental HRQOL in the current study extended the relations among the variables of personal and family life stress, family functioning, and parental mental health. This extension result could be that resilient family would talk and work together with each other and know their own strengths to draw on so that family members could rely on and share the burden and responsibility for each other, and in turn help parents reduce their parental stress and indirectly increase their HRQOL through the reduce of their parental stress.

The current study has several limitations. First, using existing data has its own limitations. For example, the dataset used was combined from two years of surveys; there might be repeated samples. The repeated samples might have some influence on the statistical analysis. Second, the scales of the latent variables for the current study were constructed by the selected items from a national survey. These scales probably would not be able to equate with a well-developed scale. Third, the respondents did not identify what assessment or definition was used for the diagnosis of their child’s ASD. Fourth, the participating parents self-reported their responses to the survey questions. Thus, perceptions of resilience, stress level, and health status are subjective. Even if they rated these questions the same on the scale, they might not experience at the same level. Finally, using cross-sectional data, such as this study, could not make causal inferences.

The interrelations among parental HRQOL, family resilience, and parental stress from the results of the current study might have some important implications for collaboration between service providers and families. Specifically, this might help practitioners develop interventions to enhance factors found to be protective and mitigate factors found to be risk (e.g., parental stress), so as to promote parental HRQOL. For example, service providers could offer opportunities to help families with children with ASD develop social and problem-solving skills; this might promote self-efficacy and family cohesion, and thus help the families with their resilience. Through reducing parental stress and improving family resilience, parental HRQOL of these families could be enhanced.

For further study, the following recommendations are suggested. Among these three important aspects, the longitudinal relations are needed to be further examined. Also, future research could include more variables (e.g., parenting coping styles, child’s age, social support) to understand their interrelations with family resilience as an outcome factor. In sum, the current study assists to examine the relations among family resilience, parental stress, and parental HRQOL for families of children with ASD.

References

Bekhet, A. K., Johnson, N. L., & Zauszniewski, J. A. (2012). Resilience in family members of persons with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Issue in Mental Health Nursing, 33, 650–656. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2012.671441

Bennett, D. A. (2001). How can I deal with missing data in my study? Australian and New Zealand. Journal of Public Health, 25(5), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2001.tb00294.x

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

Cheatham, K. L., & Fernando, D. M. (2022). Family resilience and parental stress in families of children with autism. The Family Journal, 30(3), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807211052494

Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (2021). 2018–2019 National Survey of children’s Health (2 years combined data set): Child and family health measures, national performance and outcome measures, and subgroups, SPSS Codebook, Version 1.0, Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by Cooperative Agreement U59MC27866 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau(MCHB).

Chuang, I. C., Tseng, M. H., Lu, L., Shieh, J. Y., & Cermak, S. A. (2014). Predictors of the health-related quality of life in preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1062–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.05.015

Cicchetti, D., & Lynch, M. (1993). Toward an ecological / transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry, 56(1), 96–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624

Feetham, S. (2011). The relationship of family to health: Historical overview. In M. C. Rosenberg (Ed.), Encyclopedia of family health (pp. xxxi–xxxvi). Sage.

Fong, V., Gardiner, E., & Iarocci, G. (2021). Satisfaction with informal supports predicts resilience in families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 25(2), 452–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320962677

Garmezy, N., Masten, A. S., & Tellegen, A. (1984). The study of stress and competence in children: A building block for developmental psychopathology. Child Development, 55(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129837

Halstead, E., Ekas, N., Hastings, R. P., & Griffith, G. M. (2018). Associations between resilience and the well-being of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder and other developmental disabilities. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 1108–1121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3447-z

Hoffman, C. D., Sweeney, D. P., Hodge, D., Lopez-Wagner, M. C., & Looney, L. (2009). Parenting stress and closeness: Mothers of typically developing children and mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357609338715

Hsiao, Y-J. (2016). Pathways to mental health-related quality of life for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Roles of parental stress, children’s performance, medical support, and neighbor support. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.10.008

Hsiao, Y-J. (2018). Parental stress in families of children with disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 53(4), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053451217712956

Iacob, C. I., Avram, E., Cojocaru, D., & Podina, I. R. (2020). Resilience in familial caregivers of children with developmental disabilities: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 4053–4068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04473-9

Johnson, N., Frenn, M., Feetham, S., & Simpson, P. (2011). Autism spectrum disorder: Parenting stress, family functioning and health-related quality of life. Families System & Health, 29, 232–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025341

Khanna, R., Madhavan, S. S., Smith, M. J., Patrick, J. H., Tworek, C., & Becker-Cottrill, B. B. (2011). Assessment of health-related quality of life among primary caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(9), 1214–1227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1140-6

Kim, I., Dababnah, S., & Lee, J. (2020). The influence of race and ethnicity on the relationship between family resilience and parenting stress in caregivers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 650–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04269-6

Lee, G. K., Lopata, C., Volker, M. A., Thomeer, M. L., Nida, R. E., Toomey, J. A., Chow, S. Y., & Smerbeck, A. M. (2009). Health-related quality of life of parents of children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 24, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357609347371

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00164

Maenner, M. J., Warren, Z., Williams, A. R., Amoakohene, E., Bakian, A. V., Bilder, D. A., Durkin, M. S., Fitzgerald, R. T., Furnier, S. M., Hughes, M. M., Ladd-Acosta, C. M., McArthur, D., Pas, E. T., Salinas, A., Vehorn, A., Williams, S., Esler, A., Grzybowski, A., Hall-Lande, J., & Shaw, K. A. (2023). Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 72(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

Masten, A. S. (2007). Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 921–930. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579407000442

Masten, A. S., & Monn, A. R. (2015). Child and family resilience: A call for integrated science, practice, and professional training. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 64(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12103

McStay, R. L., Trembath, D., & Dissanayake, C. (2014). Stress and family quality of life in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Parent gender and the double ABCX model. Journal of Autism Developmental Disorder, 44, 3101–3118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2178-7

Meadan, H., Halle, J. W., & Ebata, A. T. (2010). Families with children who have autism spectrum disorders: Stress and support. Exceptional Children, 77, 7–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/001440291007700101

Menezes, M., Soland, J., & Mazurek, M. O. (2023). Association between neighborhood support and family resilience in households with autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-023-05951-6

Oelofsen, N., & Richardson, P. (2006). Sense of coherence and parenting stress in mothers and fathers of preschool children with developmental disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 31(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250500349367

Patterson, J. M. (2002). Integrating family resilience and family stress theory. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00349.x

Peer, J. W., & Hillman, S. B. (2014). Stress and resilience for parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A review of key factors and recommendations for practitioners. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 2, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12072

Plumb, J. C. (2011). The impact of social support and family resilience on parental stress in families with a child diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Doctorate in Social Work (DSU) Dissertation, 14.

Prata, J., Lawson, W., & Coelho, R. (2019). Stress factors in parents of children on the autism spectrum: An integrative model approach. International Journal of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health, 6(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.21035/ijcnmh.2019.6.2

Ruiz-Robledillo, N., De Andrés-García, S., Pérez-Blasco, J., González-Bono, E., & Moya-Albiol, L. (2014). Highly resilient coping entails better perceived health, high social support and low morning cortisol levels in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35(3), 686–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.12.007

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2004). A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

ten Hoopen, L. W., de Nijs, P. F. A., Duvekot, J., Greaves–Lord, K., Hillegers, M. H. J., Brouwer, W. B. F., & van Hakkaart, L. (2022). Caring for children with an autism spectrum disorder: Factors associating with health- and care-related quality of life of the caregivers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders,52, 4665–4678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05336-7

Tung, L., Huang, C., Tseng, M., Yen, H., Tsai, Y., Lin, Y., & Chen, K. (2014). Correlates of health-related quality of life and the perception of its importance in caregivers of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(9), 1235–1242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.06.010

Turnbull, A. P., Summers, J. A., & Brotherson, M. J. (1984). Working with families with disabled members: A Family systems Approach. Research & Training Center on Independent Living, University of Kansas.

Urbanowicz, A., Nicolaidis, C., Houting, J. D., Shore, S. M., Gaudion, K., Girdler, S., & Savarese, R. J. (2019). An expert discussion on strengths-based approaches in autism. Autism in Adulthood, 1(2), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.29002.aju

Walsh, F. (2016). Applying a family resilience framework in training, practice, and research: Mastering the art of the possible. Family Process, 55(4), 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12260

Yin, S., Njai, R., Barker, L., Siegel, P. Z., & Liao, Y. (2016). Summarizing health-related quality of life (HRQOL): Development and testing of a one-factor model. Population Health Metrics, 14, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-016-0091-3

Zimmerman, M. A., & Arunkumar, R. (1994). Resiliency research: Implications for schools and policy. Social Policy Report: Society for Research in Child Development, VIIII(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.1994.tb00032.x

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the use of Data Source from the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 2018–2019 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) Combined Data Set. However, the author is responsible for the interpretations and conclusions derived from the data in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hsiao, YJ. Parental stress, family resilience, and health-related quality of life: parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06687-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06687-x