Abstract

This study examines why employees in positive informal relationships may engage in unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB). Drawing on social exchange theory and social cognitive theory, we examined the potential relational mechanisms of workplace friendships on UPB with a sample of 431 new-generation employees from different Chinese companies. The results of the empirical study indicated that workplace friendship and affective commitment were significantly positively related to UPB, as was the indirect effect of workplace friendship on UPB through affective commitment, and that a caring ethical climate (CEC) strengthened the positive relationships between workplace friendship and affective commitment and between affective commitment and UPB. Furthermore, male, married, and basic supervisor/ middle management employees were likelier to participate in UPB than female, unmarried, and general staff. These findings suggest that workplace friendships, affective commitment, and CEC may have a previously unexplored dark side. This study deepens the understanding of the environmental and personal factors that influence employee participation in UPB and contributes to the literature on the potential negative consequences of positive factors. We also discuss essential theoretical and practical implications and future research directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Guess what? Unethical behavior can cost organizations and society trillions of dollars in annual economic losses (Moore et al., 2012). Taking fraudulent activities alone, the economic loss of businesses globally due to fraudulent activities in 2010 was about 2.9 trillion dollars, which was already over 5 trillion dollars in 2019 (Mishra et al., 2022). These statistics are too frightening, implying that unethical behavior may be far more prevalent and trending upward than the famous business scandals reported in the news media (Moore et al., 2012). Furthermore, unethical behavior harms the interests of stakeholders and, more importantly, threatens the organization’s long-term development (Jannat et al., 2022). Therefore, a growing scholarly interest is in studying unethical behavior (Bryant & Merritt, 2021). The results of existing studies suggest that the drivers of unethical behaviors in organizations are highly complex and may be influenced by factors such as leader characteristics, individual employee characteristics, and organizational characteristics (Lin et al., 2018; Lian et al., 2022). The findings of these studies are sufficient to show that unethical behaviors do not occur in a vacuum (Tang et al., 2022).

Moreover, not all unethical behaviors are driven by employee interests. As Umphress and Bingham (2011) said, “Employees may engage in unethical behaviors, such as lying, to benefit the organization.” This not only broadens the perspective of the study of unethical behavior in business but also emphasizes that some employee behaviors may have a “dual” nature of being “pro-organizational” and “unethical” (Tang et al., 2022). Therefore, Umphress and Bingham (2011) define actions that are intended to promote the effective functioning of the organization or its members (e.g., leaders) and violate core societal values, mores, laws, or standards of appropriate behavior as unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB).

Since UPB has the paradoxical nature of being pro-organization and unethical (Chen et al., 2023), there may be positive and negative impacts (Tang et al., 2020). For example, employees who participate in UPB are more likely to feel guilty and, in turn, attempt to compensate for their unethical behavior through positive behavior (Tang et al., 2020), which in turn impacts their performance (Fehr et al., 2019). Conversely, the ambivalent nature of UPB may also further exacerbate employees’ anxiety, which in turn may lead to work-family conflict (Liu et al., 2021). In addition, individuals’ different attitudes towards UPB can also influence employees’ subsequent behaviors, such as incivility, avoidance of interactions, and whistleblowing (Tang et al., 2022). In conclusion, although UPB has “pro-organizational” characteristics, it is still a form of unethical behavior, which is hugely detrimental to the long-term development of an organization. Therefore, focusing on and exploring the potential antecedents of UPB and effectively curbing it is of great significance to academic research and practical work.

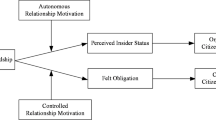

Social cognitive theory suggests that people, environments, and organizational behaviors constantly interact (Wood & Bandura, 1989). Therefore, the emergence of UPB should be extremely close to the interaction between the individual and the environment or other subjects (Mishra et al., 2022). In addition, employees often engage in UPB from the mindset of helping the organization build a good reputation or protecting the organization’s interests (Tang et al., 2022). Therefore, most scholars start from an interpersonal perspective with emotional factors as a midpoint (Park et al., 2023) to explore the factors affecting UPB further, and we believe there is a strong rationale for this path. Therefore, we chose affective commitment as a mediating variable between workplace friendships and UPB. Of course, based on real-world situational considerations, employees’ behaviors must occur in the organizational environment, so the environment will inevitably intervene in employees’ behaviors. Therefore, we further introduced the caring ethical climate (CEC) as a moderating variable to explore the moderating role of CEC in each path of the mediation model. The specific theoretical model is depicted in Fig. 1.

This study makes several contributions to the literature by opening the black box between workplace friendships and UPB. Firstly, UPB stems primarily from affective interactions between employees and the organization or other individuals, but previous studies have primarily focused on the leader-employee relationship (Bryant & Merritt, 2021). This study highlights that employees have closer relationships with their colleagues than with their leaders (Hayton et al., 2012) and that workplace friendships lead to positive outcomes for the organization and some potentially negative effects. For example, workplace friendships may lead to the proliferation of informal groups within an organization (Methot et al., 2016). Therefore, we explore the potential dark side of workplace friendships by exploring the affective interactions between employees and their colleagues, aiming to bridge the gap in the existing literature and thus enrich the antecedent research on UPB.

Secondly, affective commitment, as the primary affective factor inducing employees’ participation in UPB (Grabowski et al., 2019), is usually considered to be triggered by affective interactions between the organization or leader and employees in previous studies. We emphasize, however, that frequent affective interactions between employees and colleagues also lead to affective commitment (Anderson & Martin, 1995) and further result in employee participation in UPB. In this regard, we not only explored the mechanism of workplace friendships on UPB but also were able to enrich the antecedent research on affective commitment.

Third, when exploring the antecedents of UPB, previous studies have mainly considered the influence of single factors. We emphasize through the social cognitive theory that employees adapt their cognition and subsequent behaviour to changes in the external environment (Frese & Fay, 2001). Therefore, we considered the influence of significant others in the organization on employee behavior and the role of climate in the organizational environment. In this regard, we enrich the boundary effects literature in UPB antecedent studies by exploring the intervening role of the external environment in UPB antecedents, linking environmental factors and interpersonal interactions.

Additionally, in previous research on UPB, some scholars have also focused on differences in demographic information, but mostly in simple discussions, for example, using demographic information as control variables. This study explicitly analyses UPB’s differences in demographic information, which will help practitioners identify which groups are relatively more likely to participate in UPB. Thus, prevention and intervention measures will be targeted to them. This will also deepen scholars’ understanding of UPB’s complexity and improve the applicability of theories related to UPB in different contexts.

Finally, the new generation of employees (Millennials and Gen Z; Li & Yang, 2023) already accounts for more than half of the global workforce (Lee, 2022), and their behavioral choices are directly related to the future development of organizations (Warner & Zhu, 2018). Several studies have highlighted that new-generation employees typically emphasize justice at work (Zhu et al., 2015); for example, over 80% of millennials are unwilling to continue working for organizations that engage in unethical behavior (Su & Hahn, 2022). This may seem to make it unreasonable to associate the new generation of employees with UPB. However, as the largest group of employees in current organizations, it is unlikely that the emergence of UPB in organizations is unrelated to them. How and when does UPB emerge and develop in new generation employees? We sought to explore this process through this study. In addition, Confucian values serve as the ethical behavioral standards for Chinese citizens (Suseno et al., 2021), making China generally considered a collectivist country (Steele & Lynch, 2013). Although employees are less likely to participate in unethical behaviors in collectivist cultures (Smithikrai, 2014; Grijalva & Newman, 2015), UPB business scandals have been commonplace in Chinese organizations in recent years. Therefore, this study discusses UPB in the context of Chinese organizations, which helps to understand the cultural changes and provides insights for organizations situated in similar cultures.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Unethical pro-organizational behavior

As mentioned earlier, on the one hand, UPB represents actions made by individuals that benefit the organization; on the other hand, UPB can be detrimental to the interests of those outside the organization, which, of course, may also be a behavior desired by organizational managers (Alper Ay, 2021). Examples include employees concealing defects in goods or services, selling them to customers, and accountants helping organizations commit financial fraud (Luan et al., 2023). Employees, influenced by organizational identification, perceived organizational support, organizational commitment, and positive reciprocity beliefs, may be strongly motivated to participate in UPB to benefit the organization, even if they know UPB is unethical (Luan et al., 2023). Of course, employees may also be ambivalent about whether to implement UPB due to stronger moral courage and social expectations (Alper Ay, 2021). UPB may benefit the organization’s short-term interests. However, it can harm the interests of customers or other stakeholders, which could be more conducive to the organization’s long-term growth.

With the increasing wealth of research on UPB in the academic community, some scholars have conducted meta-analyses on UPB, systematically examining the antecedent conditions of UPB (Mishra et al., 2022; Luan et al., 2023). Antecedent research on UPB is similar to unethical behavior, with the vast majority being studied from the perspective of individuals, leaders, or organizations. With the gradual deepening of research, factors at the individual level of employees are gradually receiving attention, such as positive reciprocity beliefs, moral disengagement, and moral identity. The above studies are mainly based on social cognitive theory, which attributes the antecedents of UPB to the dysregulation of individual employees’ cognition and self-regulation (Bandura, 1989).

In existing research, leader-employee interactions tend to be viewed as a significant influence factor on UPB (Bryant & Merritt, 2021), with only a few studies focusing on the impact of employee-employee interactions on UPB (Cheng et al., 2022). However, the entity that most closely interacts with employees in the workplace is not their direct supervisor but the coworkers around them (Hayton et al., 2012). Many scholars have argued that interactive friendships among employees as a result of their work relationships can lead to desirable outcomes for organizations, such as improved employee attitudes toward work, increased organizational productivity, and employee retention (Song, 2006; Mao et al., 2012; Asgharian et al., 2015). However, due to organizational changes and technological upgrades, the emergence and development of workplace friendships have also become more complex (Ahmad et al., 2023), and some potential adverse effects are already emerging. Therefore, we believe it is more appropriate to focus on why workplace friendships may lead to unfavorable outcomes for firms (Pillemer & Rothbard, 2018), such as the adverse effects that may result from nepotism or favoritism (Wang et al., 2023a). Moreover, most studies have focused on the effects of workplace friendships on work performance, and few scholars have focused on their effects on individual behavior. Therefore, we sought to link workplace friendships with UPB and explore the mechanism of action between the two.

Furthermore, reciprocity is the core of social exchange theory, emphasizing that employees can reciprocate organizational support and care via participation in UPB (Luan et al., 2023). Under the reciprocity perspective, affective commitment is one of the stronger predictors of employee behavior among many affective factors (Matzler & Renzl, 2007; Mercurio, 2015), and thus, affective commitment (or organizational commitment) has frequently appeared as an antecedent of UPB in existing studies. Nevertheless, some gaps still need to be addressed in these studies.

First, affective commitment is usually triggered by employees’ affective interactions with the organization or essential individuals in the organization, but most of the existing studies have focused on the influence of the organization or leaders on employees’ affective commitment (Bouraoui et al., 2019; Marique et al., 2013; Ribeiro et al., 2018), ignoring the affective interactions between employees and colleagues. It is worth emphasizing that when the quality of affective interactions between employees and colleagues is higher, stronger workplace friendships are formed, and this affective relationship further transfers or spreads to the employee-organization relationship (Wu et al., 2023). Second, the results of existing studies on the relationship between affective commitment and UPB could be more consistent. On the one hand, many studies have confirmed affective commitment as one factor that encourages employees to participate in UPB (Grabowski et al., 2019; Qazi et al., 2019). However, on the other hand, the results of a meta-analysis on the antecedents of UPB did not support the relationship between organizational commitment and affective commitment with UPB (Luan et al., 2023). This result may be related to the few studies included in the meta-analysis, but more importantly, affective commitment may only be related to the “pro-organizational” characteristics of UPB. Therefore, we sought to link workplace friendships with affective commitment and explore the mechanisms of action between affective commitment and UPB, enriching the literature on the antecedents of UPB.

Workplace friendship

Generally, interpersonal relationships in organizations include formal rank and informal interpersonal relationships. As an informal relationship, workplace friendship refers to a close interpersonal relationship developed by employees who share hobbies, interests, or values based on working together (Berman et al., 2002; Pillemer & Rothbard, 2018).

In early research, workplace friendships were viewed as a one-dimensional concept, measured using friendship opportunities (Riordan & Griffeth, 1995). However, the one-dimensional scale is limited in that it needs to address the level of workplace friendships that employees develop using friendship opportunities. Thus, based on a synthesis of studies by Hackman and Lawler (1971) and Winstead et al. (1995), Nielsen et al. (2000) noted that workplace friendships consist of two dimensions: friendship opportunity and friendship prevalence. Friendship opportunities are the climate and environment created by the organization for employees that are conducive to building friendships at work and are a vital element in influencing informal relationships (Goetz & Boehm, 2020). Higher levels of friendship opportunities imply that the organization creates a supportive work environment and climate for employees (Xiao et al., 2020), which facilitates communication and trust among employees. Friendship prevalence refers to the quality of interpersonal relationships and the degree of interdependence among employees (Nielsen et al., 2000). Higher levels of friendship prevalence mean employees receive great support from their coworkers. Overall, workplace friendships encompass characteristics such as being voluntary, informal, characterized by shared norms, and driven by socio-affective goals (Pillemer & Rothbard, 2018), making them high-quality interpersonal relationships. However, existing studies do not make a strict distinction between the two and often use friendship prevalence as a measure of workplace friendship (Ugwu et al., 2022; Fasbender et al., 2023). Of course, some studies have noted the drawbacks of measuring only one dimension (Zhuang et al., 2020) and have included both dimensions in their studies and found that they work similarly (Durrah, 2023).

According to social exchange theory, people typically enter into and maintain exchange relationships with others, expecting to receive something in return (Gouldner, 1960). Suppose both parties follow the reciprocity principle of resource exchange. In that case, their interaction will continue to improve, and trust between them will be enhanced (Zeb et al., 2023), and this interaction can theoretically explain the emergence and development of workplace friendships. Like other informal relationships in organizations, workplace friendships are often perceived to have positive consequences for both the organization and the employee, mainly regarding work attitudes, behaviors, and consequences. Existing research has found that high workplace friendships can positively affect employees’ work engagement, well-being, organizational identification, and organizational commitment, help improve burnout, job stress, and job insecurity, and reduce turnover intentions. In addition, employees will also exhibit more knowledge-sharing behaviors, interpersonal citizenship behaviors, innovative behaviors, and organizational citizenship behaviors in high levels of workplace friendships, improving employee performance (Sias, 2009; Lee & Ok, 2011; David et al., 2023). The positive effects of workplace friendships on organizations have been widely validated (Zhang et al., 2022). However, workplace friendships can also contribute to the flooding of informal groups within organizations or the depletion of employee resources (Methot et al., 2016). When this occurs, workplace friendships may lead to negative employee behaviors (Zhuang et al., 2020).

Whether UPB, as a negative behavior, is affected by workplace friendships is unknown. However, we make the following reasonable speculations based on social exchange theory. First, workplace friendships enable employees to perceive organizational support for developing friendships (David et al., 2023). When employees develop stronger friendships with their colleagues, they may develop a stronger affiliation with the organization, leading to the perception that they should give back to the organization. This perception may lead them to participate in UPB for the organization’s benefit. Second, employees may choose to sacrifice short-term ethical standards to maintain long-term relationships (Zhuang et al., 2020), and the lack of ethical standards is an essential factor that induces employees to participate in UPB. In addition, workplace friendships enable employees to share organizational benefits with colleagues (Zhang et al., 2022), which means that all members may benefit when the organization is successful. Therefore, employees may participate in UPB for the expected benefits. Based on the above analyses, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

H1: Workplace friendship is positively related to UPB.

The mediating role of affective commitment

The concept of organizational commitment suggests that the more time employees spend working in an organization, the more affective commitment they develop, while their identification with the organization evolves into organizational commitment (Liou, 2008). Affective commitment, as an essential dimension of organizational commitment, represents the state of employees’ psychological attachment to the organization and reflects the positive relationship between the two (Sharma & Dhar, 2016). It strengthens employees’ identification with the organization, commitment to their work, and sense of honor as a member (Meyer & Allen, 1991) and effectively predicts employees’ behavior and emotions (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). Therefore, effectively increasing the level of affective commitment of employees is also an essential part of organizational success. According to social identity theory, when people realize they belong to a particular social group, they create a sense of belonging and value as a group member (Arshad et al., 2022). Scholars have identified employee satisfaction (Matzler & Renzl, 2007), perceived organizational support (Marique et al., 2013), corporate social responsibility (Bouraoui et al., 2019), and transformational leadership (Ribeiro et al., 2018), among others, as essential antecedents for the emergence of affective commitment. Current research has focused primarily on the influence of organizations or leaders on employees’ affective commitment. It is worth noting, however, that the subjects in the workplace who interact most frequently with employees are the coworkers around them. Thus, the affective commitment generated by employees will also stem from interactions with coworkers. When workplace friendships have a positive effect on an organization, they represent a positive interpersonal relationship (Berman et al., 2002), which facilitates the development of a pleasant and harmonious working environment in the organization and, in turn, reduces employees’ stress and frustration (McKeown & Ayoko, 2020), improves employees’ emotional connection to the organization (Lee et al., 2022), and effectively reduces employee turnover. Non-task-oriented communication (e.g., affective communication) has been shown to increase employees’ organizational commitment (Anderson & Martin, 1995), and organizations that foster a friendly environment will undoubtedly serve as a source of emotional support for employees and a bridge for emotional bonding. The deeper the friendship between employees, the stronger the sense of security felt in the organization and the degree of emotional attachment to the organization (Wu et al., 2023).

Several recent studies have also explored the negative consequences of employees’ positive psychological factors. For example, while affective commitment has often been associated with positive consequences in previous research, it has now been tentatively demonstrated that it may be significantly related to the “paradoxical” negative consequences of UPB (Grabowski et al., 2019; Qazi et al., 2019). This also means that affective commitment may be a personal factor in encouraging employees to participate in UPB. In addition, most of the existing studies exploring UPB from an interpersonal perspective use affective factors as a midpoint (Mishra et al., 2022; Luan et al., 2023), and affective commitment is one of the strongest predictors of employee behavior among many affective factors (Matzler & Renzl, 2007; Mercurio, 2015). Based on the theoretical framework of a cognitive-affective processing system, individuals with higher levels of affective commitment have a sense of identity and belonging to the organizational situation. This psychological response increases their involvement in organizational activities (Klein et al., 2012), creating a strong obligation for employees to give back and ultimately adopt certain behaviors. With this logic, we believe that employees with higher levels of affective commitment to their organizations are more likely to act in blind or even unethical ways to protect the organization’s interests.

In summary, workplace friendships enhance the affective connection between employees and the organization, which generates affective commitment to the organization. When affective commitment is successfully generated, employees are more likely to adopt UPB to protect the organization’s interests. Based on the above analyses, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

H2: Workplace friendship is positively related to affective commitment;

-

H3: Affective commitment is positively related to UPB;

-

H4: Affective commitment mediates the positive relationship between workplace friendships and UPB.

The moderating effect of caring ethical climate

Because employees within the same organization work in similar environments and are governed by the same policies, procedures, and codes of ethics, they tend to have similar perceptions of the ethical climate. At the same time, such perceptions may have a degree of stability (Wang & Hsieh, 2012). As part of the organizational climate, the ethical climate reflects employees’ shared perceptions of the organization’s ethical policies, practices, and procedures (Victor & Cullen, 1988). Although there is still some controversy about the types of ethical climate, most scholars still agree with Victor and Cullen (1988), who categorized ethical climate into five types: law and code, caring, instrumental, independence, and rules. Unlike other types of ethical climate, the emergence of CEC implies that the organization upholds the principle of altruism and cares for the interests of each employee (Li & Peng, 2022).

According to the logic of the social cognitive theory, employees adjust their cognition depending on their environment and adopt certain behaviors to be consistent with the environment (Frese & Fay, 2001). This also means that when employees are at a high level of CEC, they are more likely to feel cared for by the organization (Zhang & Cao, 2021) and thus establish good friendship relationships with other members of the organization, generating a more substantial affective commitment to the organization, and ultimately generate a tendency to maintain the interests of the organization and further act in favor of the interests of the organization (Huang et al., 2012). This logic may be one of the main pathways to UPB’s emergence. Conversely, when the level of CEC formed in the organization is low, it is difficult for the employees to feel a strong sense of belonging from it, and thus, they are unable to form a robust affective commitment, which ultimately affects the employees’ view of the organization’s interests and fails to link the organization’s interests with their own. Therefore, the likelihood of employee participation in UPB is lower. Based on the above analyses, we propose the following hypotheses:

-

H5a: CEC positively moderates the positive relationship between workplace friendships and UPB. Specifically, the positive relationship is stronger when the CEC is higher;

-

H5b: CEC positively moderates the positive relationship between workplace friendships and affective commitment. Specifically, the positive relationship is stronger when the CEC is higher;

-

H5c: CEC positively moderates the positive relationship between affective commitment and UPB. Specifically, the positive relationship is stronger when the CEC is higher.

Demographic characteristics

Relevant studies generally agree that demographic characteristics must be considered when examining employees’ psychological and behavioral aspects (Becker et al., 2016). Although previous studies have revealed that UPBs significantly differ in demographic characteristics (Luan et al., 2023), we would also like to emphasize that the results of these studies have yet to develop a unified understanding.

Specifically, regarding gender, females may exhibit higher ethical standards due to social role expectations (Eagly & Karau, 2002). However, males and females may also perform similarly unethical behaviors in certain egalitarian national cultures (Chen et al., 2016). Employees with higher levels of education have relatively higher levels of human capital investment and are typically less likely to participate in UPB (Zhang & Zhou, 2024), but may also make UPB more profitable (Luan et al., 2023). In terms of age, younger individuals may be more willing to take risks than older (Bryant & Merritt, 2021). Furthermore, since tenure and position typically show a strong positive relationship with age, it is possible to exhibit similar results. However, several studies have also emphasized that there may be complex or curvilinear relationships between age, tenure, position and UPB (Dadaboyev et al., 2024).

We suggest the inconsistent results above are due to the different theoretical bases chosen for these studies. Given that the purpose of this study was to explore the antecedents of UPB, we chose the social cognitive theory, which has been most widely used in studies of UPB’s antecedents, as the theoretical foundation (Mishra et al., 2022; Luan et al., 2023). Through the lens of social cognitive theory, this study posits that males to the societal valorization of power and competitive dynamics are more predisposed to participate in UPBs construed as manifestations of authoritative exercise. In contrast, females are more inclined to avoid participating in behaviors that may damage their reputations or are incompatible with their gender roles because of societal expectations and self-identity (Chen et al., 2016). Employees with higher levels of education typically have more excellent cognitive abilities and critical thinking and value personal reputation, which may help them recognize and resist UPB (Zhang & Zhou, 2024). Furthermore, with increasing age, employees accumulate more work experience and social knowledge, and they may better understand how to participate in UPB more covertly. Similar to this logic, employees with longer tenure and higher positions may identify more deeply with the organization and, therefore, may choose to participate in UPB due to pursuing the organization’s goals and considerations of personal career development (Luan et al., 2023).

Furthermore, although work-family conflict has become a hot topic of relevant studies in recent years (Liu et al., 2021), it is worth noting that there still needs to be more research involving the effect of marital status on UPB. Based on the logic of social cognitive theory, this study suggests that when employees get married, the family pressures they face will increase. In turn, they will strive to improve their job performance (Bolino et al., 2010), which may lead them to choose UPB to avoid dismissal or pursue promotion.

In summary, all of these demographic characteristics have been shown to impact employee psychology or behavior significantly in studies in the field of organizational behavior (Becker et al., 2016; Bernerth & Aguinis, 2016). Therefore, we focused on six critical demographic characteristics, namely gender, age, tenure, position, education level, and marital status (also the control variables we used subsequently, Becker, 2005; Bernerth & Aguinis,2016). In addition, reverse causality does not challenge these demographic characteristics, making it easier to conclude causality. We therefore propose the following hypotheses:

-

H6a: Male employees are more likely to participate in UPB than female employees;

-

H6b: Older employees are more likely to participate in UPB than younger employees;

-

H6c: Longer-tenured employees are more likely to participate in UPB than shorter-tenured employees;

-

H6d: Employees in senior positions are more likely to participate in UPB than employees in junior positions;

-

H6e: Employees with lower education levels are more likely to participate in UPB than employees with higher education levels;

-

H6f: Married employees are more likely to participate in UPB than unmarried employees.

Method

Sample and procedure

This study used convenience sampling to administer a questionnaire to a group of new-generation employees (born after 1980) in China. To ensure the authenticity and validity of the sample, we collected data using the paid sampling service provided by Wenjuan (https://www.wenjuan.com/). Wenjuan has already established partnerships with Peking University, Tsinghua University, Walmart, and many other well-known organizations and has already collected over 2.08 billion pieces of data. Before starting the data collection, we provided Wenjuan with the requirements for the sample group, which mainly included: (a) current employees who have signed an employment contract with the company (representing that the participant has a stable job); (b) employees born after 1980; and (c) the type of company in which the employee works as a limited liability company, which is also the most predominant type of company in China. In addition, to ensure the authenticity and validity of the data collection, we also required the participant’s response process through the following measures: (a) limiting the number of responses from the Internet link (only one response per device or IP); (b) the order of the scale items varied across participants (randomly disrupted); and (c) setting up random interference questions (e.g., this question, please choose option “B” directly, or simple number crunching questions; Curran, 2016).

Wenjuan obtained informed consent from all participants and also ensured anonymity and confidentiality for all participants. In the end, the researcher only received coded data that did not contain any information that could identify the participants. The questionnaire collection process started on July 1, 2023, and lasted about one month. Through the data overview provided by Wenjuan, 714 participants clicked on the web link for this questionnaire survey, of which 626 participants submitted fully completed questionnaires, with a response rate of 87.68%. In order to improve the quality of the questionnaire data, the following measures were taken to screen the questionnaires further:

-

a)

Deletion of questionnaires with answers arranged in “straight lines” or “wavy shapes.“

-

b)

Based on the number of questions, participants with less than 6 min of response time were removed.

-

c)

Remove samples with incorrect answers to random interference questions.

We obtained 431 valid questionnaires through these screening measures, exceeding the sample size suggested by Lund (2023). The effective rate of the questionnaire was 68.85%, which exceeds the 50% threshold suggested by Fowler (2010). Therefore, the quality of the data obtained from this survey meets the requirements of a general social science questionnaire. The majority of the participants were female (63.11%); the age of the participants was mainly concentrated in 23–27 (36.66%) and 28–32 (30.16%), i.e., the majority of the participants were born in 1990–2000 (66.82%); 71.23% of the participants had less than seven years of tenure; and 55.22% of the participants were general staff. In addition, the participants in this survey had a high level of education, with 76.80% having a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Measures

Since all the scales used in this study were initially expressed in English, we selected the Chinese versions to survey the sample population. According to the research needs, Chinese scholars localized these scales according to the back-translation procedure developed by Brislin (1970). The Chinese versions of these scales have been used for research in the Chinese context, cited many times, and published in high-quality journals in China. Therefore, these scales have been successfully tested in actual research and can be used in our study. Unless otherwise noted, all structured questionnaires in this study were scored using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Workplace friendship

The workplace friendship scale measures employees’ likelihood and quality of mutual friendship. The version developed by Nielsen et al. (2000) is more commonly used in related studies. The original workplace friendship scale consisted of two dimensions, friendship opportunity and friendship prevalence, with six questions per dimension for twelve items. Sun and Jiao (2012) tested the application of this scale in an organizational context in China. Through exploratory factor analysis, they found problems in the factor loading of three questions: “I do not feel that anyone I work with is a true friend,” “I socialize with coworkers outside of the workplace,” and “I have the opportunity to develop close friendships at my workplace,” so they suggested deleting them before using the scale. It is worth emphasizing that these three questions were deleted not because of problems with the scale itself but because of appropriate adjustments based on Chinese cultural characteristics. Since this study was also conducted in a Chinese context, we followed Sun and Jiao’s suggestion, which aligns with the scale requirements for cross-cultural research (Brislin, 1970). In addition, the structure of the scale did not change; the revised workplace friendship scale still includes two dimensions, with friendship opportunities consisting of five questions and friendship prevalence consisting of four questions. Example items include: “I have formed strong friendships at work” and “I have the opportunity to get to know my coworkers.” The higher participants’ self-reported scores on this scale indicate a higher perceived opportunity or prevalence of friendships at work.

Unethical pro-organizational behavior

We used a six-item scale developed by Umphress et al. (2010) to measure UPB, with sample items including “If it would help my organization, I would misrepresent the truth to make my organization look good” and “If it would help my organization, I would exaggerate the truth about my company’s products or services to customers and clients.” The scale asks participants to rate their willingness to engage in UPB in their organizations, and the higher the score, the stronger the employee’s tendency to engage in UPB.

Affective commitment

The affective commitment scale measures employees’ emotional attachment and identification with the organization (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001). The scale consists of six questions, with sample items including “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization” and “Remaining a member of this organization is important to me.” The higher the participants’ self-reported scores, the higher the level of identification and emotional attachment to the organization.

Caring ethical climate

The CEC scale measures employees’ perceptions of an organization’s supportive and caring atmosphere (Victor & Cullen, 1988). The scale consists of five questions, with sample items including “In this company, people look out for each other’s good.” and “Our major concern is always what is best for the other person.” The higher the participants’ self-reported scores on this scale, the more they feel included and cared for in the organization.

Control variables

Bernerth and Aguinis (2016) suggested that in the data analysis section, not only is it necessary to include control variables that may be potentially related to the focal variable, but also to select appropriate control variables based on empirical relationships and theories found in previous studies. Therefore, we combined previous studies and selected gender, age, tenure, education level, position, and marital status as control variables in this study (Umphress et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2022; Luan et al., 2023). These variables have been shown in previous studies to have a possible impact on employees’ UPB.

Data analysis

This study used IBM SPSS V26 and Amos V28 software for data analysis. SPSS software is used for descriptive statistical analysis, reliability testing, and correlation analysis. This study used the PROCESS macro V4.1 developed by Hayes to test the data for mediation and moderation effects. The advantages of using it are as follows. First, it can dramatically simplify the steps of mediated effects analysis by automatically handling Bootstrap and Sobel tests for mediated effects. Second, it can automatically process the data (e.g., centralization, product term calculation) before performing the moderated effects analysis. In addition, it can handle mediated or moderated effects models with control variables, allowing for more convenient handling of mediated models with moderation (Hayes et al., 2017). In addition, given the low power of Harman’s single-factor test, this study used Amos software to implement a control for the effects of an unmeasured latent method factor method (ULMC) to test for common method bias (Tang & Wen, 2020).

Results

This section first tested the questionnaire data for common method bias. Second, we examined correlations between variables and differences in demographic characteristics of UPB. Finally, we examined the relationship between workplace friendships, affective commitment, and CEC with UPB.

Common method bias test

Since all data in this study were self-reported by participants, there may be an issue of common method bias. In addition to measures such as anonymity and confidentiality, this study used Harman’s one-factor test to conduct exploratory factor analyses of all scale items. The results showed that the first factor had an explanatory rate of 32.13%, less than the critical value criterion of 40% (Tang & Wen, 2020). In addition, given the limitations of Harman’s one-factor test, we also used the ULMC method as a supplementary test for common method bias to ensure the study’s rigor.

First, we build the M1 model with only trait factors. The results showed that the leading fit indices of the model were close to ideal: χ2/df = 1.910, CFI = 0.918, TLI = 0.909, RMSEA = 0.046, and SRMR = 0.044, indicating that the questionnaire design is structurally valid. Second, a two-factor model, M2 including the method factor, was built, and the two models were compared to obtain the following differences in fit indices: Δχ2/df = 0.268, ΔCFI = 0.029, ΔTLI = 0.027, ΔRMSEA = 0.007, and ΔSRMR = 0.007. The results showed that the difference between the fitted indices of the two models was less than 0.03, which indicates that the models were not significantly improved with the addition of the common method factor. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is no significant difference between the two models, which means that there is no significant common method bias in the data of this study (Lian et al., 2018).

Correlation analysis

The correlations between all variables in this study are shown in Table 1. Workplace friendship (r = 0.74, p < 0.01) and affective commitment (r = 0.60, p < 0.01) were all significantly and positively related to UPB. In addition, gender (r = -0.12, p < 0.05), age (r = 0.12, p < 0.05), marital status (r = 0.16, p < 0.01), tenure (r = 0.12, p < 0.05), and position (r = 0.16, p < 0.01) were also significantly related to UPB.

Difference analysis

To further explore the mechanism of UPB occurrence, we tested for differences in UPB on some demographic information. Before performing the variance analysis, we tested the data for normal distribution, but the results did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, the parametric test could not be selected. In the selection of nonparametric test methods, considering that the independent variables included both two independent sample subgroups (gender) and multiple independent sample subgroups (age, education, etc.), the Mann-Whitney U test (when two independent sample subgroups are included) and the Kruskal-Wallis H test method (when multiple independent sample subgroups are included) were selected for nonparametric test. In addition, we performed all paired multiple comparisons to analyze the variance for multiple independent sample subgroups. The results of the variance analysis are shown in Fig. 2, indicating that significant differences in UPB were observed across gender, marital status, and position (only the results with significant differences are shown).

Specifically, male, married, and basic supervisor/ middle management employees were more likely to participate in UPB than female, unmarried, and general staff. These results support hypotheses H6a, H6d, and H6f. Also, we did not find significant differences in age, education level, and tenure among UPBs; therefore, hypotheses H6b, H6c, and H6e were not supported. This may be related to the sample limitation of this study. In this study, the participants’ birth years were mainly concentrated between 1990 and 2000 (66.82%); 71.23% of the participants had tenure of less than seven years. Moreover, the educational level of the participants was generally higher (76.80% of participants had undergraduate degrees and above), which contributed to one reason for the non-significant difference in the results.

Hypothesis testing

Regression analysis

To improve the model’s accuracy, we introduce gender, age, and other factors as control variables (including in the analysis of mediation and moderation effects), which are used to reduce the interference of confounding variables in estimating relevant effects. Simple linear regression results showed that workplace friendships were significantly and positively related to UPB (β = 0.71, p < 0.01), and hypothesis H1 was preliminarily tested.

Mediating effect analysis

In the analysis of mediation effects, we first introduce control variables. Then, we standardize all data and use the nonparametric percentile bootstrap method with deviation correction with 5000 sampling and 95% confidence intervals. Finally, we used the PROCESS macro program developed by Hayes (2018) to test for mediating effects. We selected Model 4 from this plug-in as the base model (Model 4 is a simple mediation model) to examine the role of affective commitment in the relationship between workplace friendships and UPB.

Based on the results of the mediation effects analysis (Table 2), we found that, as expected, workplace friendships were significantly and positively related to UPB (β = 0.71, p < 0.01). Furthermore, when we added affective commitment to the model, the positive relationship between workplace friendship and UPB remained significant (β = 0.55, p < 0.01), and hypothesis H1 was supported. Of course, the positive relationships between workplace friendship and affective commitment (β = 0.58, p < 0.01) and affective commitment and UPB (β = 0.26, p < 0.01) were also significant, and hypotheses H2 and H3 were successfully tested.

In addition, we further analyzed the indirect effect of workplace friendship on UPB, and the results are shown in Table 3. Specifically, the indirect effect of workplace friendship on UPB through affective commitment was significant (β = 0.13, boot 95% CI [0.08, 0.20]), with the indirect effect accounting for 21.57% of the total effect, supporting hypothesis H4.

Moderating effect analysis

We further use Model 59 in the PROCESS macro program (Model 59 assumes that all paths of the mediation model are moderated) to test the moderated mediation model, and the results are shown in Table 4. Specifically, there was a significant interaction between workplace friendships and CEC on affective commitment (β = 0.29, p < 0.01) but not on UPB (β = -0.02, ns). In addition, there was a significant interaction between affective commitment and CEC on UPB (β = 0.22, p < 0.01).

To better understand the pattern of interactions, we plotted simple slope plots of the interactions. We take the scores of CEC above the mean plus one standard deviation as the high grouping (M + 1SD) and the scores of CEC below the mean minus one standard deviation as the low grouping (M − 1SD). As shown in Fig. 3, the relationships between workplace friendship and affective commitment (β = 0.25, p < 0.01) and affective commitment and UPB (β = 0.09, p < 0.05) were significant and positively related at low levels of CEC and more so at high levels of CEC (β = 0.61, 0.34; p < 0.01). Thus, these results support H5b and H5c, but hypothesis H5a was not supported.

Discussion

This study takes the new generation of employees as the research object and explores the path and boundary conditions of workplace friendships affecting UPB. The study’s results indicated a positive direct and indirect relationship between workplace friendship and UPB and that the indirect positive relationship is realized through affective commitment. In addition, CEC amplified the indirect relationship. In other words, CEC served as a boundary condition to strengthen the positive relationships between workplace friendship and affective commitment, and affective commitment and UPB.

First, as we expected, there was a significant positive correlation between workplace friendships and UPB. Previous studies on UPB are mainly based on social cognitive theory and social exchange theory (Mishra et al., 2022). These studies suggest that the reasons that lead employees to engage UPB mainly lie in the reciprocal process between the employee and the organization and the employee’s cognitive process (Luan et al., 2023). Although no previous research has focused on the effects of workplace friendships on UPB, social exchange theory can help us explain this finding (Kieserling, 2019). On the one hand, workplace friendship is, by nature, a mutual and voluntary close relationship (Pillemer & Rothbard, 2018), which helps employees form a positive identity within the organization. On the other hand, when employees receive support (both material and moral) from others within the organization, they may try to give back (Chernyak-Hai & Rabenu, 2018). Of course, this relationship does not only exist between individuals. When organizations provide support and resources to their employees, employees may also engage in pro-organizational behaviors in return. Therefore, workplace friendships can form informal relationships between employees. This informal relationship can have a positive impact on employees and organizations, such as increasing employee job satisfaction or job performance; and, of course, it can also lead to deviant behaviors in the workplace (Zhuang et al., 2020) or other harmful outcomes (Pillemer & Rothbard, 2018).

Second, we also found a mediating role for affective commitment. Specifically, workplace friendships may lead to the development of affective commitment, which can further contribute to UPB in new-generation employees. This finding enriches the mechanism of action of workplace friendships on UPB in new-generation employees. Negative behaviors resulting from workplace friendships can be understood in terms of the dual characteristics of UPB. Since UPB has both “pro-organizational” and “unethical” characteristics (Tang et al., 2022), employees’ cognition of these two characteristics swayed based on their states (Chen et al., 2023). When organizations provide employees with more opportunities for friendship or the prevalence of friendships, the likelihood of establishing informal relationships among employees is more significant. Their emotions are more likely to be fulfilled, and therefore, more likely to view UPB as giving back to the organization (at this time, the “pro-organization tendency” of employees is more potent), leading to UPB. Especially for new-generation employees, their emotional needs may be more potent than their material needs (Ni et al., 2022). When new-generation employees’ emotional needs are met, they are more likely to view organizational goals as their own, leading to UPB.

Third, this study also found that CEC moderated the mediating path of affective commitment, but this moderating effect was insignificant in the direct effect of workplace friendships on UPB. This finding could enrich the boundary conditions under which UPB occurs. Expanding on social cognitive theory (Wood & Bandura, 1989), we argue that with high levels of CEC, factors such as harmony, mutual support, and pleasantness abound within the organizational environment, which makes it easier for employees to establish friendship bonds with each other, which in turn leads to greater recognition of and reliance on, the organization and their affective commitment level is also more robust (Li & Peng, 2022). When employees’ affective commitment is successfully established, CEC will further promote affective commitment, resulting in a change in the employee’s behavior. Their behavioral tendency to choose “pro-organizational” is also stronger. However, this study did not find that CEC could influence the correlation between workplace friendships and UPB. This is different from our expectations, but we also found similar conclusions to this finding in existing research (Wei & Zhang, 2020). The reasons for this conclusion lie in the essence of CEC, a standard guideline the organization provides for employees to adopt when dealing with ethical issues, and workplace friendships are composed of informal relationships between employees. Secondly, informal relationships may further contribute to forming informal groups in the organization, which is a significant factor that leads to the disruption of established rules (Alshammri, 2021). Therefore, informal groups in organizations are more likely to undermine the development of CEC. Together, CEC can promote “healthy” workplace friendships that generate affective commitment among employees. However, it does not affect “unhealthy” workplace friendships because, in this case, the relationship between workplace friendships and CEC cancels each other out. Therefore, CEC could not moderate between workplace friendships and the direct relationship with UPB.

Finally, we also found that UPB had significant differences in gender, marital status, and position. In terms of gender, male employees are more likely to participate in UPB than female employees, which is supported by many previous studies (Lian et al., 2022; Luan et al., 2023). In Chinese culture, males are often expected to play more positive, proactive, and competitive roles. They are also likely to be viewed as the primary breadwinners of their families. Such gender role expectations may motivate male employees to participate in UPB to pursue career success (Luan et al., 2023). In terms of position, employees in senior positions are more likely to participate in UPB than those in junior positions. Based on specific values in Chinese organizations, such as Mianzi and Guanxi, may prompt employees in senior positions to participate in UPB to uphold these values (Zhang & Zhou, 2024). In addition, employees in senior positions usually have more power and decision-making autonomy and are under more pressure; therefore, they may participate in UPB in the absence of supervision in order to achieve performance goals.

Furthermore, few previous studies have linked employees’ marital status to UPB, and this study innovatively proposes and validates that married employees are more likely to participate in UPB than unmarried employees. This result should be discussed in the context of traditional Chinese culture. In China, general employees wanting to enter into a marriage relationship must consider their financial situation (Keldal & Şeker, 2022). For example, in the preparatory stage of marriage, males may face economic requirements such as buying a house, a car, and the “bride price” (Duan et al., 2022); after marriage, both spouses need to face the economic pressures of mortgage payments, car loans, raising children, and supporting parents. Therefore, we argue that due to family or financial pressures after marriage, general employees are more concerned about job promotion or avoiding dismissal because their job is their primary source of income. As a result, general employees, after marriage, appreciate their jobs more, which may induce them to increase their job performance and try to contribute to the organization through some dishonorable means (UPB).

Theoretical contributions

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, we enrich current research on the antecedents of UPB from the perspective of informal relationships. As mentioned earlier, much of the current research on the antecedents of UPB focuses on the effects of leader-employee interactions on UPB (Bryant & Merritt, 2021). However, research on the effects of informal relationships formed by employee-employee interactions on UPB has yet to be emphasized. This study is an expansion of social cognitive theory. Since the reasons employees choose to implement UPB are very complex, we should pay more attention to various individuals that can impact employees. This study confirmed that the employee-employee interpersonal relationship is also an essential factor influencing individuals’ behavioral choices, which broadens the idea of studying the antecedents of UPB from a relational perspective.

Second, this study broadens the applicability of workplace friendships in relevant research. Current research on the consequences of workplace friendships focuses on employees’ work attitudes or performance. Although some scholars have already begun to pay attention to the adverse effects of workplace friendships (Wang et al., 2022), no research has explored the mechanism of workplace friendships on the complex individual behavior of UPB. The mechanism of the occurrence and development of workplace friendships in organizations is usually complex. The relevant research results still need to be improved, and the research on the consequences of workplace friendships is relatively single. This study innovatively links workplace friendships with UPB, which helps to enrich the research on the relationship between workplace friendships and individual behaviors.

Third, the introduction of affective commitment and CEC variables in this study helps us better analyze the mechanism of action and boundary conditions of the effect of workplace friendships on UPB. Previous studies have mainly focused on the influence of the leader-employee relationship on affective commitment (Mumtaz & Rowley, 2020), and we further enriched the antecedent research of affective commitment by broadening the antecedents to an employee-employee relationship. In addition, we introduce CEC, a moderating variable that echoes social cognitive theory. It is essential to establish a rich moderating mechanism in exploring UPB, and CEC can be regarded as an environmental variable in reciprocal determinism, helping us explain why benign variables can lead to the paradox of UPB.

Finally, we also found differences in some demographic information exhibited by UPB. As mentioned above, many previous studies have focused on gender, age, tenure, and other factors (Lian et al., 2022), and we innovatively propose that employees with different marital statuses may have different levels of UPB. Indeed, there have been studies that have begun to focus on the impact of variables involving family factors, such as work-family conflict, on employee behavior (Tu et al., 2022) or that have explored antecedent variables of unethical pro-family behavior (Wang et al., 2023b). These studies have been very enlightening. In China’s work environment, where the boundary between work and family is blurred (Peng et al., 2022), employees’ family status is bound to impact their organizational behaviors. This study found that different marital statuses of employees lead to different levels of UPB tendencies. This relatively cutting-edge conclusion can significantly enrich the perspective of UPB research and shed light on the study of related factors such as unethical pro-family behavior. Of course, this study’s limitation of the sample group to new-generation employees is also novel. Since new-generation employees possess different personalities from other generations (Warner & Zhu, 2018), they have also become a significant force in organizations worldwide. This study can enrich the research findings on the behavior of new-generation employees in organizations and expand the sample population for UPB-specific research.

Practical implications

The conclusions drawn from this study also have important implications for management practice. For managers, UPB is often hidden under a “pro-organizational” appearance, so managers should pay more attention to the factors that can lead to UPB. Controlling the antecedents of UPB is also an essential means of effectively curbing UPB (Luan et al., 2023).

First of all, managers should pay attention to the correction and management of workplace friendships. Workplace friendships help employees establish deep emotional ties with each other. They also help them build identification with the organization, improve their sense of belonging, and thus enhance their work performance (Methot et al., 2016). Therefore, managers can encourage employees to collaborate in work teams while appropriately increasing cross-team and cross-departmental communication and cooperation. In addition, an open and friendly organizational climate can be created by carrying out collective activities that benefit employees’ physical and mental health, such as staff birthday parties and fun sports, to create good conditions for forming and developing workplace friendships. Of course, the disadvantages of informal relationships formed by workplace friendships cannot be ignored (Wang et al., 2022), and managers need to develop appropriate systems to regulate and guide the formation of “healthy” informal relationships among employees.

Second, managers must consider the “appropriate” construction of affective commitment. Increased levels of affective commitment have been shown to promote UPB, so we argue that there are also two types of affective commitment, “rational” and “blind.” When employees are in a state of blind affective commitment, they are more likely to disregard the requirements of the system or norms and engage in UPB; on the contrary, when employees are in a state of rational, affective commitment, they can demonstrate their loyalty to the organization on the one hand, and the other hand, they also regulate their behaviors, and thus the greater the likelihood that they will engage in “ethical pro-organizational behavior.”

Finally, managers should choose appropriate management styles based on the different demographic characteristics of their employees. For example, employees who have just entered into marriage often face the pressure of building a “new family,” and the economic pressure of raising children and supporting parents will make them exhausted. Therefore, managers can set specific personal work goals for them following departmental objectives, give them appropriate free working time, and allow them to choose their workplace freely. This way, employees can allocate their time to work and family according to their circumstances. In addition, male employees’ ethical decisions tend to be based on rules and power, while female employees’ ethical judgments mainly stem from their responsibilities to others (Fulmore et al., 2024). Therefore, managers can develop differentiated education and training programs to improve the moral literacy of employees of different genders in a targeted manner. Of course, organizations should also strengthen the supervision of employees in senior positions as a way to circumvent the more hidden UPB.

Limitations and future research directions

Although our conclusions can contribute to theory and practice, some limitations remain. First, although we explored the effect of employee-employee relationships on UPB relatively innovatively, we did not examine the possible effects of other individuals. Future research could combine leader-employee relationships with employee-employee relationships to explore further the strength of the influence of superiors and peers on employee behavior within an organization and to improve the antecedent research on UPB. Secondly, this study only adopts the method of employee self-reporting when collecting data, which is relatively simple. Therefore, the leader-employee matching survey method can be adopted in future research to eliminate subjective differences further. In addition, the results of this study may only apply to some specific regions, given the significant differences in cultural backgrounds between regions. Comparative studies could be conducted in the future for similar developing or developed countries. Finally, although we found that UPB significantly differed across employees of different genders, marital statuses, and positions and point to the frontiers of these findings, the effect mechanisms of these demographic characteristics on UPB are unclear. In this study, we only made inferences from practical experience. Accordingly, future research can delve into the differential manifestations of demographic characteristics on UPB and propose targeted intervention measures by integrating relevant theories.

Conclusion

Through empirical investigation of Chinese employees, this study found that: (a) Workplace friendship is positively related to UPB; (b) The positive relationship between workplace friendship and UPB was indirectly influenced by affective commitment.; (c) CEC strengthened the positive relationships between workplace friendship and affective commitment and between affective commitment and UPB; and (d) Male, married, and basic supervisor/ middle management employees were likelier to participate in UPB than female, unmarried, and general staff. The results of this study not only enriched the research on the antecedents of UPB and the dark side consequences of workplace friendships but also found that such dark side consequences are realized via the indirect role of affective commitment and the boundary role of CEC. At the same time, this study provides some suggestions for managers’ practice based on the findings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahmad, R., Ishaq, M. I., & Raza, A. (2023). The blessing or curse of workplace friendship: Mediating role of organizational identification and moderating role of political skills. International Journal of Hospitality Management,108, 103359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103359

Alper Ay, F. (2021). Yapsam Da Yapmasam Da Sorun Olabilir! Etik Olmayan Organizasyon Yanlısı Davranışlar (EOOYD). In K. Aydin (Ed.), Örgüt Geliştirme ve Örnek Uygulamalar (pp. 61–94). Iksad Publications.

Alshammri, S. N. (2021). Do informal groups threaten organizations? Comparing group conflict management styles with supervisors. Independent Journal of Management & Production,12(4), 997–1018. https://doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v12i4.1342

Anderson, C. M., & Martin, M. M. (1995). Why employees speak to coworkers and bosses: Motives, gender, and organizational satisfaction. The Journal of Business Communication (1973),32(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194369503200303

Arshad, M., Qasim, N., Farooq, O., & Rice, J. (2022). Empowering leadership and employees’ work engagement: A social identity theory perspective. Management Decision,60(5), 1218–1236. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2020-1485

Asgharian, R., Anvari, R., Ahmad, U. N. U. B., & Tehrani, A. M. (2015). The mediating effect of job satisfaction on the relationship between workplace friendships and turnover intention in Iran hotel industry. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences,6(6 S2), 304–314. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2015.v6n6s2p304

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist,44(9), 1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Becker, T. E. (2005). Potential problems in the statistical control of variables in organizational research: A qualitative analysis with recommendations. Organizational Research Methods,8(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105278021

Becker, T. E., Atinc, G., Breaugh, J. A., Carlson, K. D., Edwards, J. R., & Spector, P. E. (2016). Statistical control in correlational studies: 10 essential recommendations for organizational researchers. Journal of Organizational Behavior,37(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2053

Berman, E. M., West, J. P., & Richter, M. N. Jr. (2002). Workplace relations: Friendship patterns and consequences (according to managers). Public Administration Review,62(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00172

Bernerth, J. B., & Aguinis, H. (2016). A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Personnel Psychology,69(1), 229–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12103

Bolino, M. C., Turnley, W. H., Gilstrap, J. B., & Suazo, M. M. (2010). Citizenship under pressure: What’s a good soldier to do? Journal of Organizational Behavior,31(6), 835–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.635

Bouraoui, K., Bensemmane, S., Ohana, M., & Russo, M. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment: A multiple mediation model. Management Decision,57(1), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2017-1015

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Bryant, W., & Merritt, S. M. (2021). Unethical pro-organizational behavior and positive leader-employee relationships. Journal of Business Ethics,168(4), 777–793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04211-x

Chen, C. W., Tuliao, V., Cullen, K., J. B., & Chang, Y. Y. (2016). Does gender influence managers’ ethics? A cross-cultural analysis. Business Ethics: A European Review,25(4), 345–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12122

Chen, M., Chen, C. C., & Schminke, M. (2023). Feeling guilty and entitled: Paradoxical consequences of unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Business Ethics,183(3), 865–883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05109-x

Cheng, K., Wang, Y., Lin, Y., & Wang, J. (2022). Observer reactions to unethical pro-organizational behavior and their feedback effects. Advances in Psychological Science,30(9), 1944–1954. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2022.01944

Chernyak-Hai, L., & Rabenu, E. (2018). The new era workplace relationships: Is social exchange theory still relevant? Industrial and Organizational Psychology,11(3), 456–481. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2018.5

Curran, P. G. (2016). Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,66, 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.07.006

Dadaboyev, S. M. U., Paek, S., & Choi, S. (2024). Do gender, age and tenure matter when behaving unethically for organizations: Meta-analytic review on organizational identity and unethical pro-organizational behavior. Baltic Journal of Management,19(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-12-2022-0480

David, N. A., Coutinho, J. A., & Brennecke, J. (2023). Workplace friendships: Antecedents, consequences, and new challenges for employees and organizations. In A. Gerbasi, C. Emery, & A. Parker (Eds.), Understanding workplace relationships (pp. 325–368). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16640-2_11

Duan, Z., Jin, X., & Teng, J. (2022). Typological features and determinants of men’s marriage expenses in rural China: Evidence from a village-level survey. Sustainability,14(14), 8666. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148666

Durrah, O. (2023). Do we need friendship in the workplace? The effect on innovative behavior and mediating role of psychological safety. Current Psychology,42(32), 28597–28610. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03949-4

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review,109(3), 573–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.3.573

Fasbender, U., Burmeister, A., & Wang, M. (2023). Managing the risks and side effects of workplace friendships: The moderating role of workplace friendship self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior,143, 103875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2023.103875

Fehr, R., Welsh, D., Yam, K. C., Baer, M., Wei, W., & Vaulont, M. (2019). The role of moral decoupling in the causes and consequences of unethical pro-organizational behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,153, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.05.007

Fowler, F. J. (2010). Survey research methods. SAGE Publications.

Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2001). Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior,23, 133–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23005-6

Fulmore, J. A., Nimon, K., & Reio, T. (2024). The role of organizational culture in the relationship between affective organizational commitment and unethical pro-organizational behavior. Journal of Managerial Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-11-2022-0581. Advance online publication.

Goetz, T. M., & Boehm, S. A. (2020). Am I outdated? The role of strengths use support and friendship opportunities for coping with technological insecurity. Computers in Human Behavior,107, 106265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106265

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review,25(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

Grabowski, D., Chudzicka-Czupała, A., Chrupała‐Pniak, M., Mello, A. L., & Paruzel‐Czachura, M. (2019). Work ethic and organizational commitment as conditions of unethical pro‐organizational behavior: Do engaged workers break the ethical rules? International Journal of Selection and Assessment,27(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12241

Grijalva, E., & Newman, D. A. (2015). Narcissism and counterproductive work behavior (CWB): Meta-analysis and consideration of collectivist culture, big five personality, and narcissism’s facet structure. Applied Psychology,64(1), 93–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12025

Hackman, J. R., & Lawler, E. E. (1971). Employee reactions to job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology,55(3), 259–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031152

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs,85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Hayes, A. F., Montoya, A. K., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal,25(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

Hayton, J. C., Carnabuci, G., & Eisenberger, R. (2012). With a little help from my colleagues: A social embeddedness approach to perceived organizational support. Journal of Organizational Behavior,33(2), 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.755

Huang, C. C., You, C. S., & Tsai, M. T. (2012). A multidimensional analysis of ethical climate, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Nursing Ethics,19(4), 513–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011433923

Jannat, T., Alam, S. S., Ho, Y. H., Omar, N. A., & Lin, C. Y. (2022). Can corporate ethics programs reduce unethical behavior? Threat appraisal or coping appraisal. Journal of Business Ethics,176(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04726-8

Keldal, G., & Şeker, G. (2022). Marriage or career? Young adults’ priorities in their life plans. The American Journal of Family Therapy,50(5), 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2021.1915213

Kieserling, A. (2019). Blau (1964): Exchange and power in social life. In B. Holzer, & C. Stegbauer (Eds.), Schlüsselwerke der Netzwerkforschung (pp. 51–54). Netzwerkforschung. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-21742-6_12

Klein, H. J., Molloy, J. C., & Brinsfield, C. T. (2012). Reconceptualizing workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: Revisiting assumptions and removing confounds. Academy of Management Review,37(1), 130–151. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2010.0018

Lee, Y. (2022). Dynamics of millennial employees’ communicative behaviors in the workplace: The role of inclusive leadership and symmetrical organizational communication. Personnel Review,51(6), 1629–1650. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-09-2020-0676

Lee, J. J., & Ok, C. (2011, January 6). Effects of workplace friendship on employee job satisfaction, organizational citizenship behavior, turnover intention, absenteeism, and task performance. Graduate Student Research Conference in Hospitality and Tourism. Retrieved December 30, 2023, from https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14394/29951

Lee, A. Y. P., Chang, P. C., & Chang, H. Y. (2022). How workplace fun promotes informal learning among team members: A cross-level study of the relationship between workplace fun, team climate, workplace friendship, and informal learning. Employee Relations,44(4), 870–889. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-06-2021-0251

Li, X., & Peng, P. (2022). How does inclusive leadership curb workers’ emotional exhaustion? The mediation of caring ethical climate and psychological safety. Frontiers in Psychology,13, 877725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.877725

Li, X., & Yang (2023). Facilitate or diminish? Mechanisms of perceived organizational support on employee experience of new generation employees. Psychological Reports. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941231183621. Advance online publication.

Lian, S., Liu, Q., Sun, X., & Zhou, Z. (2018). Mobile phone addiction and college students’ procrastination: Analysis of a moderated mediation model. Psychological Development and Education,34(5), 595–604. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2018.05.10