Abstract

Employee well-being has been a focus of interest in social and organizational psychology research and maintains considerable implications for organizational overall performance and growth. Burnout and its core component, emotional exhaustion (EE), have been frequently used as a standard measure of employee well-being in research. Grounded in the assumptions of the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory, the purpose of the present study was to examine job embeddedness (JE) and its sub-dimensions of fit, links, and sacrifice, as mediators of the association between work locus of control (WLOC) and burnout, as measured by EE. The study included 161 multidisciplinary employees with a minimum of one-year tenure from diverse organizations. Data were collected at two-time points, with one month apart. The findings showed that JE fully mediated the association between WLOC and EE, explaining 22% of the variance in EE. Examining each of the JE sub-dimensions showed that fit and sacrifice, but not links, individually, served as full mediators of the association between WLOC and EE. The results attest to the important impact of JE on employees’ well-being and provide additional understanding of the processes by which WLOC leads to workplace well-being. The discussion includes both theoretical and practical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Employee well-being has been a focus of interest in social and organizational psychology research mainly because it has considerable implications for organizational overall performance and growth (Guthier et al., 2020; Maslach, 2017). Dysfunctional well-being has been a predictor of job performance, employee retention, and physical health (Wright & Huang, 2012). The findings suggest that personal and contextual factors interact with each other and have a differential effect on employee well-being. Despite the wealth of accumulated knowledge, job stress is growing worldwide and is estimated to affect over 50 million individuals in the European Union alone (Guthier et al., 2020). Moreover, the Covid-19 pandemic and the social distancing regulations imposed to control the spread of the virus have been linked to increased rates of job insecurity, work-family conflicts, and other health-related strains (e.g., Nemteanu et al., 2021; Zacher & Rudolph, 2021). The deteriorated working conditions have increased the likelihood of employees facing job burnout (Kniffin et al., 2021). Additionally, workplace burnout has recently been officially included by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the 11th edition of its International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), as an occupational phenomenon that leads individuals to contact health services (Guthier et al., 2020). Therefore, exploring the factors affecting burnout may provide both theoretical and practical contributions.

This research aims to deepen our understanding of employee well-being by applying the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) to analyze how work locus of control (WLOC) interacts with burnout risk within the framework of job embeddedness (JE). This study is pioneering in its integration of these three distinct constructs into a unified model, thus addressing a significant gap in existing scholarship. By employing the foundational formative measure of JE, this study provides a detailed examination of how embeddedness components impact employee well-being. From a practical standpoint, our findings may serve to create tailored interventions designed to enhance embeddedness and minimize burnout risk, while adjusting to employees’ levels of WLOC. This innovative method of measuring and interpreting the effects of JE offers substantial contributions to our understanding of the intricate dynamics that affect work-related psychological health. The subsequent sections will examine each research variable and discuss the principles of COR theory as the foundation for formulating the hypotheses of this study.

Theoretical background

Burnout

Burnout represents a state of both psychological and physical condition characterized by depletion or fatigue, resulting from exposure to chronic job stressors (Maslach et al., 2001; Maslach & Jackson, 1981). According to Maslach (2017, p. 144), “workers who are experiencing burnout are overwhelmed, unable to cope, and unmotivated, and they display negative attitudes and poor performance.” Burnout has been of particular interest to many stakeholders because it impacts both the individual as well as society (Guthier et al., 2020). Burnout has detrimental effects on mental and physical well-being and job performance (Guthier et al., 2020; Leiter & Maslach, 2003; Lemonaki et al., 2021; Maslach, 2017; Maslach et al., 2001) and as such results in a considerable economic loss due to an increase in absenteeism and turnover rates, low morale, incivility and a rise in healthcare costs (Borritz et al., 2006; Maslach, 2017).

Situational, environmental, and personal variables play important roles in predicting burnout. More specifically, Leiter and Maslach (2003) describe burnout as an outcome of person-job incompatibility. The authors identified six key areas in which these imbalances may occur and increase employee vulnerability to burnout: work overload (both physical and emotional), lack of control and autonomy at the job, lower than expected rewards (whether monetary, social, or intrinsic), lack of support and trust in the workplace, perceived unfairness or inequality, and conflict between organizational and employee values (Leiter & Maslach, 2003; Maslach, 2017).

Burnout comprises three dimensions—interpersonal (characterized by cynicism and detachment), self-evaluation (involving feelings of reduced personal accomplishment), and physical-emotional (marked by emotional exhaustion) (Leiter & Maslach, 2003). At the heart of these components is emotional exhaustion (EE), which Leiter and Maslach (2003, p. 93) describe as “feelings of being overextended and depleted of one’s emotional and physical resources.” Recognized as the fundamental aspect of burnout, EE is often used independently to assess the condition (Guthier et al., 2020; Sonnentag et al., 2010). Research has consistently shown that EE is closely linked to several critical workplace outcomes such as job performance, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee turnover (Cropanzano et al., 2003; Lee & Ashforth, 1996; Tourigny et al., 2013; Wright & Cropanzano, 1998). Considering its pivotal role in the burnout syndrome and its established connections with significant work-related outcomes, the current study will specifically address EE as the primary measure of burnout. This focus underscores the importance of EE in understanding and addressing burnout in the workplace.

Given the significant impact of burnout and EE on both individuals and organizations, it is important to examine the factors that may contribute to or mitigate these experiences. One such factor that has been consistently linked to employee well-being is locus of control.

Locus of control

Locus of Control (LOC) is one of the most frequently studied individual variables in social research and it effectively predicts attitudes, emotions, and behaviors (Ng et al., 2006). It can be described as the degree to which people perceive having control over the consequences of events that occur in their lives (Hernandez et al., 2022). Rotter (1966) differentiates internal LOC from external LOC. Individuals with an internal LOC (internals) believe that their actions and personal qualities lead to results, while individuals with an external LOC (externals) perceive that outcomes are governed by external forces (Galvin et al., 2018). Internals are self-assured, attentive, and take charge while trying to influence their external surroundings. Furthermore, they frequently see a strong link between their actions and the subsequent outcomes. Externals, conversely, perceive themselves as playing a passive role in their external environment and tend to ascribe personal outcomes to luck or external forces (Ng et al., 2006). In the work context, LOC is related to many outcomes. Specifically, internal LOC is strongly associated with job satisfaction and job performance, job motivation, task performance, investment in training, career success, social experiences, and interpersonal relationships at work (Caliendo et al., 2022; Judge & Bono, 2001; Ng et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2010).

The link between perceived control and burnout has been well-established in the literature. Numerous studies have demonstrated that internal LOC is positively associated with individuals’ burnout and general well-being in and outside of work (Judge et al., 1998; Spector, 1988; Spector et al., 2002; Spector & O’Connell, 1994; Wang et al., 2010). Employees who experience a lack of control or autonomy in their work due to role conflicts, inconsistent demands, or incongruent values are more likely to experience EE, as they struggle to set priorities and fully engage in their work (Leiter & Maslach, 2003; Cordes & Dougherty, 1993). LOC plays a significant role in this relationship, as individuals with an internal LOC (internals) tend to perceive their job as offering more autonomy compared to those with an external LOC (externals) (Spector, 1982). Consequently, internals are less likely to experience role conflicts and the associated EE (Ng et al., 2006).

Job embeddedness

Building on the relationship between LOC and burnout, it is important to consider other factors that may influence this association. One such factor that has gained increasing attention in the organizational psychology literature is job embeddedness (JE). The concept of JE (Mitchell et al., 2001) was originally developed to assess the contextual forces that encourage an individual employee to remain within an organization. This original model of job retention included two spheres in which these forces operate: organizational (on-the-job) and community (off-the-job). The former emphasizes elements within the organizational environment that embed the employee (e.g. a good pension plan), whereas the latter concentrates on elements within the community that embed the individual (e.g. quality of environment and presence of recreational opportunities) (Lee et al., 2004). These forces are measured across three factors: Links, Fit and Sacrifice. The “links” component refers to the level of individuals’ connections to other people or activities, both within their work environment and within their community. The “fit” component refers to the extent to which the individual’s values, aspirations, and plans fit with the organization’s culture or with the surrounding environment. The “sacrifice” component refers to the perceived material or psychological merits that may be lost by leaving the organization or the community. The greater the links, fit and sacrifice, the more the person is bound to the organization (Lee et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2001).

While Mitchell et al. (2001) initially introduced JE as a unified concept, subsequent research in organizational psychology has predominantly emphasized organizational embeddedness to predict work-related outcomes (Burton et al., 2010; Lev & Koslowsky, 2012; Ng & Feldman, 2010, 2011, 2013; Peltokorpi et al., 2022). In line with this focus, our study exclusively explores the organizational embeddedness component, as we aim to investigate job-related factors that may impact well-being.

A sizeable amount of research has demonstrated that (JE) is a significant predictor of turnover (Coetzer et al., 2019; Crossley et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2004; Mallol et al., 2007; Mitchell et al., 2001; Qian et al., 2022), as well as other work-related outcomes such as job performance(Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2008; Lee et al., 2004; Safavi & Karatepe, 2019; Sun et al., 2012) and citizenship behavior (Lee et al., 2004; Lev & Koslowsky, 2012).

Early research on JE primarily focused on its positive impact on organizational outcomes, yet recent studies have shifted attention toward its effects on employee well-being. Several investigations have identified negative correlations between JE and burnout indicators (e.g., Candan, 2016; Goliroshan et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020, 2022; Zhou & Chen, 2021), suggesting that embeddedness may serve as a protective factor for well-being.

Despite the extensive focus on the outcomes of JE in existing research, there remains much to learn about the antecedents of embeddedness, particularly regarding what motivates certain employees to become more embedded than others. In a pioneering study, Ng and Feldman (2011) have demonstrated that individuals with an internal LOC are more likely to engage in proactive behaviors that shape their work environment, resulting in increased embeddedness.

.

The conservation of resources (COR) theory

The relationships between WLOC, JE, and employee well-being can be understood through the lens of the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989). The COR theory is a motivational theory that explains human conduct based on the evolutionary necessity of individuals to obtain and safeguard resources to ensure survival. Its core argument asserts that individuals strive to acquire, preserve, and protect things that hold value to them. These may include personal, social, and material resources, such as well-being, self-esteem, family, and employment. Moreover, obtaining and retaining these resources leads individuals to believe they can cope with stressful challenges. The core principles of the theory argue that individuals view resource loss as distressing and that the more resources they have, the more they can utilize them in order to defend themselves from further resource loss during stressful events in their lives (Hobfoll et al., 2018).

Building on this theoretical foundation, Kiazad et al. (2015) suggested that the idea of embeddedness and its work-related outcomes can be parsimoniously explained within the framework of the COR theory. They argued that people stay in organizations in order to retain resources and acquire more resources. Based on the tenets of the COR theory, the authors further posited that resources gained from one sphere can be utilized to replace resources lost in another sphere. For example, when embedded employees experience resource loss such as EE, they can turn to their multiple embedding resources (e.g., colleague support or feeling valued by others) for a substitute. In other words, embeddedness holds a protective effect against stresses, given that embedded employees have more resources to enable them to confront stressful situations and events compared to their less embedded counterparts. This theoretical perspective helps to understand how embeddedness influences employee well-being by providing individuals with the resources needed to cope with work-related stressors and challenges.

Similarly, the COR theoretical framework can explain the relationship between LOC and JE. embeddedness. As mentioned earlier, Ng and Feldman (2011) demonstrated the role of LOC in the embedding process. Their study, which was based on the COR theory, argued that individuals with an internal LOC are more motivated to acquire resource surpluses and to avoid resource losses than those with an external LOC. These individuals tend to engage in proactive behaviors that help them gain resources such as networking, seeking out growth opportunities, and negotiating better employment packages. These acquired resources, in turn, enhance their perceptions of embeddedness. In contrast, individuals with an external LOC may be less engaged in such resource acquisition behaviors, resulting in lower levels of perceived embeddedness (Ng & Feldman, 2011).

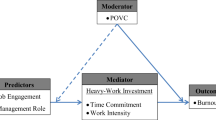

Combining these arguments, we can posit that individuals with an internal LOC are more likely to become embedded in their jobs through the acquisition of resources, and this increased embeddedness, in turn, provides them with the resources needed to maintain their well-being in the face of work-related stressors. Hence, based on the COR theory and the reviewed literature, the following conceptual model is proposed (Fig. 1).

Summary of literature review and research aims

As discussed previously, past research has provided empirical support for the relationships between LOC and JE (Ng & Feldman, 2011), and between JE and burnout (e.g., Candan, 2016; Goliroshan et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2020, 2022; Zhou & Chen, 2021). Through the lens of the COR theory, these findings suggest that individuals with an internal LOC are more inclined to engage in behaviors that enhance their JE, which may subsequently serve as a protective factor against burnout.

Despite the growing interest in the associations between JE and employee well-being, the number of studies examining these relationships remains relatively limited. Furthermore, some contradictory findings regarding the relationship between JE and EE (e.g., Allen et al., 2016; Peltokorpi, 2022) necessitate a re-examination of the nature of this association. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no study to date has investigated the potential mediating role of JE in the relationship between LOC and EE. Additionally, many studies on JE have relied on reflective measures that capture global perceptions of embeddedness (e.g. Dirican & Erdil, 2022; Ng & Feldman, 2011; Zhang et al., 2012), rather than the original formative measure developed by Mitchell et al. (2001), which assesses the specific dimensions of fit, links, and sacrifice. The differences in the measurement of JE may represent a fundamentally different methodological approach (Lee et al., 2014). Similarly, studies have often utilized general measures of LOC, as opposed to context-specific measures of work LOC (WLOC), which have been shown to yield stronger relationships with work-related criteria (Wang et al., 2010).

These gaps in the literature highlight the need for further research to understand the mechanisms through which LOC influences burnout and to provide a more thorough understanding of the role of JE and its sub-dimensions in this relationship. The current study aims to address these gaps by examining the mediating role of JE in the relationship between WLOC and EE, using the original formative measure of JE (Mitchell et al., 2001) and the context-specific measure of WLOC. By employing these measures, this study seeks to provide an in-depth understanding of how specific facets of JE contribute to the relationship between WLOC and EE, thus offering valuable insights for developing targeted interventions to mitigate the risk of burnout.

Drawing from the literature review and the gaps identified in the literature, we examined the following research questions (a) To what extent is WLOC associated with EE? (b) What is the nature of the relationship between JE and EE? (c) To what extent WLOC is associated with JE? (d) Does JE mediate the relationship between WLOC and EE? (e) And to what extent do the specific facets of JE (fit, links, and sacrifice) contribute to the relationship between WLOC and EE?

Hence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

-

H1: WLOC will be negatively correlated with EE, such that higher levels of internal WLOC will be associated with lower levels of EE.

-

H2: JE will be negatively correlated with EE, such that higher levels of JE will be associated with lower levels of EE.

-

H3: WLOC will be positively correlated with JE, such that higher levels of internal WLOC will be associated with higher levels of JE.

-

H4: JE will mediate the relationship between WLOC and EE, such that WLOC will have an indirect effect on EE through its influence on JE.

-

H5: The specific facets of JE (fit, links, and sacrifice) will differentially contribute to the relationship between WLOC and EE.

These research questions and hypotheses will guide the data analysis and interpretation presented in the upcoming sections.

Methodology

Measures

The following measures were used in the present study:

-

Work locus of control (WLOC). Participants completed a questionnaire based on Spector’s(1988) Work Locus of Control Scale, translated into Hebrew and used by Laufer (2004). While the original scale consisted of 16 items, one item (representing internal WLOC) was omitted from the Hebrew version, resulting in a total of 15 items. A sample item includes: “A job is what you make of it.” The items were scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In line with the original scoring system presented by Spector (1988), the items were recoded such that a low score represented internal WLOC, and a high score represented external WLOC. The coefficient alpha here was 0.73.

-

Job embeddedness (JE). The 26-item scale adapted from Mitchell et al.’s (2001) job embeddedness scale and translated into Hebrew by Lev and Koslowsky (2012) was used here. The scale comprises of three subscales: links to the organization (an example item: ‘‘How many work teams are you on?’’), fit to the organization (an example item. ‘‘My job utilizes my skills and talents well’’), and organization-related sacrifice (an example item: ‘‘The benefits are good on this job’’). The items in the links subscale are assessed using an open-ended numerical scale. (e.g., number of work teams), and the fit and sacrifice items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). All link items were standardized before combining items. The three subscales (fit, sacrifice, and links) were standardized and then summed to create a total embeddedness score. The reliability of the composite scale was 0.87.

-

Emotional Exhaustion (EE). Nine items representing the emotional exhaustion component from the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)(Maslach & Jackson, 1981) were adopted. The items were translated into Hebrew. A sample item: “I feel emotionally drained from my work.” The coefficient alpha here was.84.

In addition to the above measures, participants responded to several demographic indicators including gender, age, marital status (single, married or has a life partner, divorced, widow/er), education (high school or lower, technical/nonacademic, academic), work industry, tenure, and organizational hierarchical level (employee, professional worker, manager, senior manager). As none of these indicators were correlated with the dependent variable, EE, they were not included in the present analysis.

Participants

A study sample of 161 employees took part in the research. The participants were all members of an Israeli online panel (“Sekernet”). SekerNet is an internet panel established in 2007 that offers its services to research institutes and academic institutions. The panel has tens of thousands of panel members segmented by age, sex, area of residence and sectors. The panel members have expressed their agreement to participate in various studies and are compensated for doing so (as translated from the panel website). The criteria for inclusion in the study were a minimum tenure of 1 year, an age range between 22 and 67, and a full-time or nearly full-time (75% and above) position.The current study utilized a diverse sample of employees from various industries and organizational contexts. This approach is consistent with previous research on JE and related constructs, which has often relied on heterogeneous samples to increase the generalizability of the findings (e.g., Allen et al., 2016; Peltokorpi et al., 2022). The use of an online panel allowed for the recruitment of a broad range of participants, enhancing the external validity of the study. While the sample contained both full-time (84.5%) and nearly full-time (15.5%) employees, supplementary analyses revealed no significant difference in the average (standardized) scores for both JE and EE scores between these two groups. For JE, full-time employees had a mean score of 0.01 (SD = 1.02), while nearly full-time employees had a mean score of − 0.07 (SD = 0.90) with no statistical difference between the groups (t(161) = 0.35, p =.725). Similarly, for EE, full-time employees had a mean score of 0.04 (SD = 1.02), and nearly full-time employees had a mean score of − 0.24 (SD = 0.86), again with no statistically significant difference (t(161) = 1.29, p =.099). These findings indicate that including nearly full-time employees in the study did not significantly affect the overall results. Eighty-five participants (52.8%) were women. Ages ranged from 22 to 65 with a mean age of 42.04 (SD = 11.69). Seventy-two participants (44.7%) reported having some academic education and 127 (78.9%) were married or had a life partner. Employees were employed at their organizations for 1 to 40 years with a mean tenure of 8.69 years (SD = 8.61). Hundred and seven participants (66.5%) were line workers, 23 (14.3%) were professionals, and the rest were managers (16.8%) or senior managers (2.5%).

A priori power analyses were conducted using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009) for the main multiple regression model with 2 predictors and an additional model with 4 predictors, representing the examination of the 3 embeddedness factors (fit, links, and sacrifice) as mediators. In line with Cohen’s (2013) guidelines and the conventions in psychology and organizational behavior research, a medium effect size (f² = 0.15) was assumed for both analyses. For the main model with 2 predictors, α = 0.05, power = 0.80, the power analysis indicated a minimum required sample size of 68 participants. For the additional model with 4 predictors, using the same parameters, the power analysis indicated a minimum required sample size of 110 participants. The current study’s sample size of 161 exceeds both minimum requirements, providing sufficient power to detect medium effects in both the main analysis and the analysis of the individual JE factors as mediators.

Procedure

Before completing the online survey, all participants provided their consent by agreeing to a digital informed consent form. Data were collected in two phases to reduce method bias resulting from a single-survey design consisting of self-reported measures (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The EE questionnaire was completed one month after the WLOC, and JE questionnaires were completed. The scales were presented to participants in random order at each phase, which may also reduce response bias (Standing & Shearson, 2010).

At Time 1, the link to the survey was distributed to a large number of the panel members. A total of 449-panel members responded within two days, of which 149 were disqualified before completing the questionnaires because they did not meet the inclusion criteria described above. Thus, a total of 300 completed questionnaires were received. After one month, the link to the second survey was distributed to the same 300 respondents, which resulted in 161 complete responses. The 139 respondents who did not reply to the second survey did not differ significantly from the sample that was analyzed in gender χ2(df=1) = 3.20, p =.074, age t(298) = -0.06, p =.954, education χ2(df=3) = 2.54, p =.47, and hierarchical level in organization t(250) = 3.32, p =.345. There was a marginal difference in tenure in a current organization (t(294) = -1.94, p =.053) according to which the non-respondent had higher tenure (M = 10.72, SD = 9.49) compared to the final sample (M = 8.69, SD = 8.61). In addition, the final sample had a higher rate of married participants (79%) compared with non-respondents (60%) (χ2(4, N = 250)p <.001).

Data analysis

All variables were standardized and analyzed for normality. The analysis showed that most variables met the normal distribution criteria, with skewness values ranging from − 0.15 to + 0.32. An exception was the links dimension which had a skewness value of 2.17 and a kurtosis value of 7.12 indicating that the distribution was positively skewed and heavy-tailed compared to the normal distribution. Harman’s single factor test showed the first factor explained only 18.01% of the total variance, suggesting common method variance was not a substantial issue. Prior to analyzing the study hypotheses, the internal consistency of each scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The reliability coefficients for all measures demonstrated good internal consistency: WLOC, α = 0.73; JE (the composite measure), α = 0.87; and EE, α = 0.84. The Fit and Sacrifice dimensions of JE also showed good internal consistency (α = 0.89 and α = 0.80, respectively). However, the internal reliability for the Links dimension was lower (α = 0.65) (see Table 1). This is not surprising, as the links dimension is an aggregate of several indicators that do not necessarily constitute a single factor (Cortina, 1993). Additionally, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was calculated for each scale, yielding values of 0.776 for WLOC, 0.891 for JE Fit, 0.814 for JE Sacrifice, 0.684 for JE Links, and 0.863 for EE. These results suggest that the sampling adequacy for most scales was good to excellent, with the exception of the JE Links scale, which was acceptable but lower than the others. These findings support the reliability of the measures used in the study and their suitability for the planned mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018).

In addition, before analyzing the study hypotheses several demographic variables were examined including, age, gender, education, organizational hierarchical level, family status, and tenure in the current position. None of these variables significantly correlated with the dependent variable and, therefore, they were not included further in the analysis.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS 26 and the mediation hypothesis was analyzed using the Hayes PROCESS procedure in SPSS (Hayes, 2018).

Results

Table 1 summarizes the means, standard deviations, inter-correlations, and reliabilities among the study variables. The inter-correlations were all in the expected directions and significant, with the exception of the links dimension which was not found to be significantly correlated with any of the study variables, apart from the expected association with the composite variable of JE.

Analysis of hypotheses

The results of the mediation analysis, as depicted in Fig. 2, provide support for the hypothesized relationships between WLOC, JE, and EE. As predicted in H1, WLOC was significantly associated with EE (β = − 0.18, p <.01), with individuals having a more internal WLOC reporting lower levels of EE. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that an internal LOC is associated with lower levels of job burnout (e.g., Ng et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2010).

H2 posits a negative association between JE and EE. As predicted, JE was significantly negatively associated with EE (β = − 0.46, p <.01), suggesting that more embedded employees experience lower levels of EE. This finding is consistent with the implications of the COR for JE, as discussed by Kiazad et al. (2015). The authors argue that embedded individuals have more resources to cope with work-related stressors and thus are less likely to experience burnout, as they can draw upon their multiple embedding resources to replace resources lost in stressful situations.

H3 proposed a positive relationship between WLOC and JE. The results supported this hypothesis, with WLOC being significantly negatively correlated with JE (β = − 0.25, p <.01), indicating that individuals with a more internal WLOC tend to be more embedded in their jobs. This finding extends previous research by Ng and Feldman (2011), who found a significant association between LOC and perceived JE.

The mediation analysis using PROCESS (Hayes, 2018) provided support for H4, which proposed that JE would mediate the relationship between WLOC and EE. The results showed that WLOC and JE together explained a significant portion of the variance in EE (R² = 0.22, p <.001). Moreover, the indirect effect of WLOC on EE through JE was significant (indirect effect = 0.11, 95% CI [0.04, 0.20]), while the direct effect of WLOC on EE was non-significant (direct effect = 0.07, p =.37), indicating full mediation. These findings suggest that the effect of WLOC on EE can be largely explained by its impact on JE, with individuals with a more internal WLOC being more embedded in their jobs, which in turn reduces their EE.

To further investigate the role of JE in the relationship between WLOC and EE, we examined whether each individual component of embeddedness (fit, links, and sacrifice) serves as a mediator. Given that the preliminary analyses showed no significant correlation between the links dimension and either WLOC or EE, this dimension was excluded from the mediation analysis.

Using the Hayes PROCESS procedure, we found that both fit and sacrifice individually served as full mediators of the association between WLOC and EE. The indirect effect of WLOC on EE through fit was significant (indirect effect = 0.12, 95% CI [0.05, 0.22]), as was the indirect effect through sacrifice (indirect effect = 0.10, 95% CI [0.04, 0.18]). Thus, addressing H5, the findings suggest that the relationship between WLOC and EE can be explained by the extent to which individuals perceive a fit between their skills, values, and career goals and those of their organization, as well as the perceived material and psychological benefits they would have to give up if they were to leave their organization.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to explore JE as influencing employees’ wellbeing. In particular, by focusing on the COR theory we examined JE as a mediator of the association between WLOC and burnout, as measured by EE. Moreover, as opposed to previous studies that measured JE with a reflective scale that captures perceptions of embeddedness, the current study’s uniqueness derives from its ability to examine the individual contribution of each of the embeddedness components (i.e., fit, sacrifice, and links) to the mediation.

The findings showed a negative relationship between WLOC and EE, supporting H1. This aligns with previous research suggesting that an internal LOC is associated with lower levels of job burnout (e.g., Ng et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2010). Furthermore, COR theory posits that individuals with an internal LOC are more likely to engage in resource acquisition and protection behaviors, which can help them cope with work-related stressors and prevent EE.

As hypothesized in H2, the findings showed that JE predicts burnout such that highly embedded employees reported lower rates of EE. This finding supports the role of JE as a protective resource against burnout, as suggested by COR theory, and aligns with prior research linking embeddedness with favorable outcomes concerning the individual employee (Ampofo et al., 2017; Candan, 2016; Goliroshan et al., 2021; Ng & Feldman, 2013; Zhou et al., 2020; Zhou & Chen, 2021; Zhou et al., 2022). These results provide strong support to the notion that embeddedness benefits the employee no less than it benefits the organization. Despite some contradictory findings regarding the relationship between JE and EE (e.g., Allen et al., 2016; Peltokorpi, 2022), our study aligns with the majority of research linking embeddedness with favorable employee outcomes.

In addition, the results demonstrated a positive relationship between WLOC and JE, thus supporting H3. This finding extends previous findings by Ng and Feldman (2011) and aligns with COR theory’s predictions about resource acquisition behaviors. Individuals with an internal WLOC are more likely to engage in activities aimed at gaining and protecting resources, resulting in higher embeddedness.

More importantly, the results showed that JE fully mediated the association between WLOC and EE, supporting H4. Building on the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018), and following Ng & Feldman’s (2011) study, we argued that internal workers are more likely to engage in activities aimed at gaining and protecting resources, resulting in higher embeddedness. Furthermore, the accumulated resources help the employee cope with work stresses, thus mitigating exhaustion and burnout. This finding highlights the role of JE as a resource that mediates the effect of WLOC on EE, as predicted by COR theory.

Examining each of the JE dimensions (fit, sacrifice, and links) individually, revealed that the fit and sacrifice dimensions were the only contributors to the mediation relationship. The links dimension did not correlate with WLOC or EE. It is worth noting that the COR theory emphasizes the value or significance that the individual attributes to the resources. Strain only occurs when a key resource is threatened, lost, or not achieved after considerable effort (Hobfoll et al., 2018). The “links” dimension, as measured by the JE composite index, reflects the quantity of the organizational connections, not their quality, and as such may not represent key resources that the employee values. Indeed, the value that the employee gives to social relationships in the organization may be reflected in the fit and sacrifice dimensions (i.e., “I like the members of my work group”; “I feel that people at work respect me a great deal”). Moreover, in the original Mitchell et al. (2001) study, the links dimension was not significantly associated with job satisfaction, and its associations with other work-related variables were substantially lower than those of the fit and sacrifice dimensions. Taken together, these findings suggest that the components of organizational fit and sacrifice better reflect the organizational resources valued by the individual employee, which they will strive to obtain and protect, and which, in return, may help them deal with work-related stress and burnout. These findings provide partial support for H5, highlighting the differential contributions of the JE facets to the relationship between WLOC and EE.

Theoretical and practical contributions

The present study’s findings have important practical and theoretical implications. The findings suggest that employees with internal WLOC are better capable of obtaining and retaining organizational resources, resulting in high embeddedness, which further protects them from burnout. This supports the COR theory’s proposition that individuals strive to acquire and protect resources and that these accumulated resources can help them cope with work-related stressors and prevent EE. HR managers should consider JE practical importance for both organizational and employee outcomes. It is recommended that intervention programs place particular emphasis on increasing perceptions of fit with the organization’s work, team, and culture, as well as highlight the unique advantages and opportunities (social, monetary, and career-wise) offered by the company. In addition, previous research suggested that internal LOC perceptions could be increased through interventions and affect positive and desired outcomes. More specifically, Huang and Ford (2012) demonstrated that after participating in a training program, drivers reported higher levels of internality and lower levels of externality, predicting an improvement in safe driving behaviors. As such, HR managers and practitioners should consider designing intervention programs to increase internal WLOC and decrease external WLOC as a means to enhance organizational embeddedness and lessen burnout among employees.

Limitations and future research directions

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of the present study. First, all the measures employed in this study were self-reported, which may be susceptible to common method biases such as consistency motif and social desirability (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Although we attempted to mitigate these biases by introducing a temporal separation between the independent and dependent measures and randomizing the order of the scales, future research should consider incorporating objective measures or data from multiple sources to corroborate our findings.

Second, while our study’s results support the mediating role of JE in the relationship between WLOC and EE, some evidence suggests that EE and embeddedness may be inversely related, and that the former can impair embeddedness (e.g. Karatepe, 2013). Furthermore, as noted in our introduction and discussion, some recent studies argue that at certain conditions high embeddedness can be harmful to the employee’s wellbeing (Allen et al., 2016; Peltokorpi, 2022). Thus, employing a longitudinal research design that encompasses the different measures at multiple intervals over an extended period could more accurately depict the direction as well as the conditional association between JE and EE. Such a design would allow researchers to better understand the complex and potentially reciprocal relationship between these constructs, as well as identify any boundary conditions that may influence the nature of this relationship.

Third, the generalizability of our findings may be limited due to the relatively small sample size and the focus on Israeli workers. Moreover, our study included some employees working slightly less than full-time (75% or above). Future research should aim to replicate our study among larger samples of employees from different cultures to obtain a broader cross-national perspective on the relationships between WLOC, JE, and EE. Additionally, researchers could explore potential cultural differences in the way these constructs interact and influence employee well-being.

Finally, while our study focused on EE as an indicator of employee well-being, future research could extend our model by examining other relevant outcomes, such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and job performance. Investigating these additional outcomes would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of WLOC and JE on various aspects of employee well-being and work-related attitudes and behaviors.

Concluding remarks

Based on the assumptions of the COR theory, the present study originally presents JE as a mediator of the evidenced relationship between internal WLOC and employee well-being, as measured by emotional exhaustion. By examining the differential contributions of the JE facets (fit, links, and sacrifice) to this mediation, our study provides a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms through which WLOC influences burnout. These findings are particularly important and relevant in our days since the Covid-19 pandemic has increased the vulnerability of employees to burnout (Kniffin et al., 2021), and job mobility as well as different forms of contingent employment are more prevalent (Scully-Russ & Torraco, 2020). The results highlight the importance of fostering internal WLOC and JE as resources to protect employee well-being and prevent burnout, aligning with the core principles of COR theory. The findings call for further empirical examination of the effect that JE and its sub-dimensions have on employee well-being as well as practical interventions to encourage and increase embeddedness and perceptions of internal LOC.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (LB) upon reasonable request.

References

Allen, D. G., Peltokorpi, V., & Rubenstein, A. L. (2016). When “embedded” means “stuck”: Moderating effects of job embeddedness in adverse work environments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(12), 1670–1686. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000134

Ampofo, E. T., Coetzer, A., & Poisat, P. (2017). Relationships between job embeddedness and employees’ life satisfaction. Employee Relations, 39(7), 951–966. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-10-2016-0199

Borritz, M., Rugulies, R., Villadsen, E., Mikkelsen, O. A., Kristensen, T. S., & Bjorner, J. B. (2006). Burnout among employees in human service work: Design and baseline findings of the PUMA study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 34(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940510032275

Burton, J. P., Holtom, B. C., Sablynski, C. J., Mitchell, T. R., & Lee, T. W. (2010). The buffering effects of job embeddedness on negative shocks. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(1), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.06.006

Caliendo, M., Cobb-Clark, D. A., Obst, C., Seitz, H., & Uhlendorff, A. (2022). Locus of control and investment in training. Journal of Human Resources, 57(4), 1311–1349.

Candan, H. (2016). A research on the relationship between job embeddedness with performance and burnout of academicians in Turkey. Journal of Business and Management, 18(3), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-1803026880

Coetzer, A., Inma, C., Poisat, P., Redmond, J., & Standing, C. (2019). Does job embeddedness predict turnover intentions in SMEs? International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 68(2), 340–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-03-2018-0108

Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Cordes, C. L., & Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and an integration of research on job burnout. Academy of Management Review, 18(4), 621–656.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D. E., & Byrne, Z. S. (2003). The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 160–169. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.1.160

Crossley, C. D., Bennett, R. J., Jex, S. M., & Burnfield, J. L. (2007). Development of a global measure of job embeddedness and integration into a traditional model of voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1031–1042. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1031

Dirican, A. H., & Erdil, O. (2022). Linking abusive supervision to job embeddedness: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. Current Psychology, 41, 990–1005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00716-1

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160.

Galvin, B. M., Randel, A. E., Collins, B. J., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Changing the focus of locus (of control): A targeted review of the locus of control literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(7), 820–833. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2275

Goliroshan, S., Nobahar, M., Raeisdana, N., Ebadinejad, Z., & Aziznejadroshan, P. (2021). The protective role of professional self-concept and job embeddedness on nurses’ burnout: Structural equation modeling. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00727-8

Guthier, C., Dormann, C., & Voelkle, M. C. (2020). Reciprocal effects between job stressors and burnout: A continuous time meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 146(12), 1146–1173. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000304

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Wheeler, A. R. (2008). The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work and Stress, 22(3), 242–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802383962

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100

Hernandez, J. M. C., Costa Filho, M., Kamiya, A. S. M., Pasquini, R. O., & Zeelenberg, M. (2022). Internal locus of control and individuals’ regret for normal vs. abnormal decisions. Personality and Individual Differences, 192, 111562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111562

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J.-P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of Resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych

Huang, J. L., & Ford, J. K. (2012). Driving locus of control and driving behaviors: Inducing change through driver training. Transportation Research Part f: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 15(3), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2011.09.002

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits - self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability - with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80

Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., Durham, C. C., & Kluger, A. N. (1998). Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.17

Karatepe, O. M. (2013). The effects of work overload and work-family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance: The mediation of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(4), 614–634. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111311322952

Kiazad, K., Holtom, B. C., Hom, P. W., & Newman, A. (2015). Job embeddedness: A multifoci theoretical extension. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038919

Kniffin, K. M., Narayanan, J., Anseel, F., Antonakis, J., Ashford, S. P., Bakker, A. B., Bamberger, P., Bapuji, H., Bhave, D. P., Choi, V. K., Creary, S. J., Demerouti, E., Flynn, F. J., Gelfand, M. J., Greer, L. L., Johns, G., Kesebir, S., Klein, P. G., Lee, S. Y., … Vugt, M. van. (2021). COVID-19 and the workplace: Implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. American Psychologist, 76(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716

Laufer, H. (2004). Long-experienced social workers and supervision: Perceptions and implications. The Clinical Supervisor, 22(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1300/J001v22n02_10

Lee, R. L., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.2.123

Lee, T. W., Burch, T. C., & Mitchell, T. R. (2014). The story of why we stay: A review of job embeddedness. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091244

Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Sablynski, C. J., Burton, J. P., & Holtom, B. C. (2004). The effects of job embeddedness on organizational citizenship, job performance, volitional absences, and voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 47(5), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159613

Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2003). Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In P. L. Perrewe & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Emotional and physiological processes and positive intervention strategies (Research in occupational stress and well being, Vol 3) (Issue 03, pp. 91–134). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3555(03)03003-8

Lemonaki, R., Xanthopoulou, D., Bardos, A. N., Karademas, E. C., & Simos, P. G. (2021). Burnout and job performance: A two-wave study on the mediating role of employee cognitive functioning. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(5), 692–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1892818

Lev, S., & Koslowsky, M. (2012). On-the-job embeddedness as a mediator between conscientiousness and school teachers’ contextual performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 21(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2010.535656

Mallol, C. M., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Journal, S., Sep, N., & Thomas, W. (2007). Job Embeddedness in a Culturally Diverse Environment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 22(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/sl0869-007-9045-x

Maslach, C. (2017). Finding solutions to the problem of burnout. Consulting Psychology Journal, 69(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000090

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030020205

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Mitchell, T. R., Holtom, B. C., Lee, T. W., Sablynski, C. J., & Erez, M. (2001). Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1102–1121. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069391

Nemteanu, M. S., Dinu, V., & Dabija, D. C. (2021). Job insecurity, job instability, and job satisfaction in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Competitiveness, 13(2), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.7441/JOC.2021.02.04

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). The effects of organizational embeddedness on development of social capital and human capital. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(4), 696–712. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019150

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2011). Locus of control and organizational embeddedness. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317910X494197

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2013). The effects of organisational embeddedness on insomnia. Applied Psychology, 62(2), 330–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00522.x

Ng, T. W. H., Sorensen, K. L., & Eby, L. T. (2006). Locus of control at work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(8), 1057–1087. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.416

Peltokorpi, V. (2022). When embeddedness hurts: The moderating effects of job embeddedness on the relationships between work-to-family conflict and voluntary turnover, emotional exhaustion, guilt, and hostility. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(10), 2019–2051. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1803948

Peltokorpi, V., Feng, J., Pustovit, S., Allen, D. G., & Rubenstein, A. L. (2022). The interactive effects of socialization tactics and work locus of control on newcomer work adjustment, job embeddedness, and voluntary turnover. In Human Relations (Vol. 75, Issue 1, pp. 177–202). https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726720986843

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Qian, S., Yuan, Q., Niu, W., & Liu, Z. (2022). Is job insecurity always bad? The moderating role of job embeddedness in the relationship between job insecurity and job performance. Journal of Management & Organization, 28(5), 956–972.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/H0092976

Safavi, H. P., & Karatepe, O. M. (2019). The effect of job insecurity on employees’ job outcomes: The mediating role of job embeddedness. Journal of Management Development, 38(4), 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-01-2018-0004

Scully-Russ, E., & Torraco, R. (2020). The changing nature and organization of work: An integrative review of the literature. Human Resource Development Review, 19(1), 66–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484319886394

Sonnentag, S., Binnewies, C., & Mojza, E. J. (2010). Staying well and engaged when demands are high: The role of psychological detachment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 965–976. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020032

Spector, P. E. (1982). Behavior in organizations as a function of employee’s locus of control. Psychological Bulletin, 91(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.482

Spector, P. E. (1988). Development of the work locus of control scale. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 61(4), 335–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1988.tb00470.x

Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Sanchez, J. I., Driscoll, M. O., Bernin, P., Büssing, A., Dewe, P., Hart, P., Lu, L., Miller, K., Moraes, L. R. De, Ostrognay, G. M., Pagon, M., Pitariu, H. D., Poelmans, A. Y., Radhakrishnan, P., Russinova, V., Salamatov, V., Jesùs, F.,… Teichmann, M. (2002). Locus of control and well-being at work: How generalizable are Western findings? Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 453–466. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069359

Spector, P. E., & O’Connell, B. J. (1994). The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control and Type A to the subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1994.tb00545.x

Standing, L. G., & Shearson, C. G. (2010). Does the order of questionnaire items change subjects’ responses? An example involving a cheating survey. North American Journal of Psychology, 12(3), 603–603.

Sun, T., Zhao, X. W., Yang, L. B., & Fan, L. H. (2012). The impact of psychological capital on job embeddedness and job performance among nurses: A structural equation approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(1), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05715.x

Tourigny, L., Baba, V. V., Han, J., & Wang, X. (2013). Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of organizational commitment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(3), 514–532.

Wang, Q., Bowling, N. A., & Eschleman, K. J. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of work and general locus of control. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(4), 761–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017707

Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (1998). Emotional exhaustion as a predictor of job performance and voluntary turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 486–493.

Wright, T. A., & Huang, C.-C. (2012). The many benefits of employee well-being in organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1188–1192. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1828

Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. (2021). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 76(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702

Zhang, M., Fried, D. D., & Griffeth, R. W. (2012). A review of job embeddedness: Conceptual, measurement issues, and directions for future research. Human Resource Management Review, 22(3), 220–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2012.02.004

Zhou, H., & Chen, J. (2021). How does psychological empowerment prevent emotional exhaustion? Psychological safety and organizational embeddedness as mediators. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.546687

Zhou, H., Liu, S., He, Y., & Qian, X. (2022). Linking ethical leadership to employees’ emotional exhaustion: A chain mediation model. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 43(5), 734–749. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2021-0452

Zhou, H., Sheng, X., He, Y., & Qian, X. (2020). Ethical leadership as the reliever of frontline service employees’ emotional exhaustion: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030976

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

In accordance with ethical guidelines, the study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and adhered to all ethical protocols set forth by the University’s Ethics Committee. Prior to participation, informed consent was acquired from all study participants. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ben-Meir, L., Giladi, A. & Koslowsky, M. Job embeddedness as a mediator of the relationship between work locus of control and emotional exhaustion. Curr Psychol 43, 24994–25005 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06203-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06203-1