Abstract

Based on Farber’s burnout proposal, the first aim of this study was to examine the psychometric properties of the short version of the Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire (BCSQ-12) in secondary school teachers. The second aim of the study was to examine possible differences in the burnout subtypes in terms of gender, type of school, and teaching experience. Two different samples of 584 (M = 45.04; 43% males) and 106 (M = 45.50; 40% males) secondary school teachers participated in the study. Results obtained from both the exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) and the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) supported the three-factor structure of the BCSQ-12, comprised of overload, lack of development, and neglect. Further, the BCSQ-12 showed adequate composite reliability. The negative relationships between the three-factor structure of burnout, teachers’ basic psychological need satisfaction, and teachers’ job satisfaction provide evidence of the nomological validity of BCSQ-12. Finally, female teachers, state school teachers, and experienced teachers reported a greater risk of suffering one or more of these three burnout subtypes. Theoretical, methodological, and practical contributions of the BCSQ-12 are discussed, highlighting the importance of assessing the three burnout subtypes separately.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The burnout syndrome is one of the major public health problems worldwide, in particular in human service professions (García-Carmona et al. 2018; Innstrand et al. 2011). In the teaching context, burnout leads to ensuing emotional and psychological costs for teachers (e.g., high stress, low satisfaction, anxiety or sleep problems; Gluschkoff et al. 2016; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2016; Yu et al. 2015), but it also causes organizational costs for schools and educational administrations (e.g., low job performance and high absenteeism; Lackritz 2004; Moriana and Herruzo 2006; Ryan et al. 2017). Further, teacher burnout has also been related to how teachers interact with their students, which becomes a key factor in students’ motivation and academic achievement (Abós et al. 2018c; Klusmann et al. 2016).

All these consequences have made teacher burnout an increasing concern, not only for many researchers, interested in identifying sociodemographic and psychological characteristics that affect burnout, but also for school stakeholders, interested in the well-being of teachers (von der Embse et al. 2016). One of the most effective ways of reducing burnout is to design, implement, and evaluate specific strategies and intervention programs aimed at preventing it (Iancu et al. 2018). It is important, therefore, to measure burnout via an instrument that focuses on the characteristics of the teaching profession and that is able to differentiate between the burnout subtypes they may experience. To do so, the present study relies on Farber's (1990, 1991, 2000) proposal, which was initially raised in an educational setting, to examine the psychometric properties in secondary school teachers of the short version of the Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire (BCSQ-12) developed by Montero-Marín et al. (2011c).

Burnout Models and Definitions

Since workers affected by burnout came to light through observations by Freudenberger (1974), numerous descriptions of this syndrome have been found in literature (Farber 2000; Gil-Monte 2005; Maslach and Jackson 1986; Pines and Aronson 1988). However, it was not until a decade later when the evaluation of burnout became available, through the development of one of the most popular scales, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach and Jackson 1986). In its most recent version (Maslach et al. 1996), the MBI considers burnout as a prolonged response to chronic stressors at work and it is defined by the three dimensions of exhaustion (i.e., feelings of being emotionally overextended, depletion, and fatigue), cynicism (i.e., a development of distant behavior toward work and colleagues), and inefficacy (i.e., the feeling of not conducting tasks adequately). The MBI has been used in numerous working populations to measure burnout. In fact, it has been slightly adapted to better fit different professional profiles such as human services (MBI-HSS), educators (MBI-ES), and even students (MBI-SS) (for further information, see Maslach et al. 1996). However, all these versions are based on a general framework that is unable to capture the specific characteristics of each particular case (Montero-Marín et al. 2009). Further, they contemplate burnout as a syndrome with relatively consistent symptoms in all individuals as a response to chronic stress at work (Montero-Marín et al. 2009). This not only increases the difficulty of identifying different types of burnout experienced by teachers, but it also hinders addressing specific strategies to cope with the burnout subtypes.

A Burnout Model to Capture Teaching Job Characteristics

According to Farber (1990), the burnout prevention strategies to be applied should be based on the characteristics and symptoms experienced by each person. That is, a level of specification in the treatment, attending to individual differences, that would need to consider the provenance of the feelings of frustration and stress factors experienced, the resources to cope with them, and the symptoms manifested (Farber 2000). Thus, from a more phenomenological point of view than the one provided by Maslach’s definition, three different burnout subtypes were tentatively proposed by Farber (1990, 1991, 2000). This theoretical framework could be more accurate for examining teacher burnout because it emerges specifically within –among others– an educational setting.

The three original subtypes proposed by Farber (1990, 1991, 2000) are frenetic, underchallenged, and wornout, which were structured and systematized in a typological definition by Montero-Marín et al. (2009) according to the level of dedication at work, to respond to chronic stress and frustration as a classification criterion. The frenetic subtype, characterized by investing a large amount of time at work, is common of people who are highly involved, ambitious, and overloaded. The underchallenged subtype, typified by feelings of indifference, boredom, and lack of personal development, is common of people who perform routine tasks. The wornout subtype, characterized by the feeling of losing control over results, the perception of lack of recognition of self-efforts, and neglecting responsibilities, is common of people who experience a rigid organizational structure at work (Montero-Marín and García-Campayo 2010; Montero-Marín et al. 2009). This burnout definition was operationalized by means of the Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire (BCSQ-36; Montero-Marín and García-Campayo 2010), which is helpful to specifically examine the burnout subtypes and to design specific strategies depending on individual characteristics. This is workable because the BCSQ-36 provides a larger framework, overcoming the limitations of MBI, which, although three-dimensional, is at the same time more broadly oriented towards a unified definition of the syndrome (Montero-Marín et al. 2012).

A short version of the BCSQ-36 has also been developed (BCSQ-12; Montero-Marín et al. 2011c), which is able to present the typological perspective of the BCSQ-36 with a more parsimonious structure. It is more manageable to administer, with better psychometric properties, and its completion is less time-consuming. The BCSQ-12 comprises overload, lack of development, and neglect factors, belonging, respectively, to the burnout subtypes identified by the BCSQ-36 (i.e., frenetic, underchallenged, and wornout). In the teaching context, overload is usually suffered by teachers who put too much time and effort into their work at the expense of their own health and personal life. Lack of development is experienced by teachers who work superficially because they perceive that it is very difficult to develop their personal skills, and their intention is to change jobs. Finally, teachers who experience neglect give up quickly in stressful situations because they perceive they do not have sufficient resources to teach and no longer care about their responsibilities.

The BCSQ-12 has been previously tested in different contexts and populations, such as university workers (Montero-Marín et al. 2011c; including teaching and research staff, administration and service personnel, and scholarship holders), dental students (Montero-Marín et al. 2011b), or primary healthcare physicians (Montero-Marín et al. 2015). In all of them, it has proved to be a reliable tool to discriminate the three burnout subtypes. However, to date, the BCSQ-12 has not specifically been validated in secondary school teachers. Considering that teaching is one of the professions whose daily schedules include a higher workload (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2015), the shortness of the BCSQ-12 could be an added point in favor of measuring burnout in the teaching context.

Correlates Associated with Teacher Burnout

The study of burnout correlates seems critical to develop prevention strategies to reduce its incidence. On the one hand, grounded in self-determination theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan 1985, 2000, 2002), satisfying the basic psychological needs (BPNs) for autonomy, competence, and relatedness is essential to reach optimal personal functioning (e.g., low burnout at work). Autonomy refers to people’s need to feel they are the causal agents of their own actions (Ryan and Deci 2017). Competence refers to perceived ability when someone is faced with a situation that threatens an important goal (White 1959). Finally, relatedness refers to the individual’s aspiration to maintain close and positive interpersonal relationships with his/her social environment and feel part of it (Deci and Ryan 2000). According to SDT principles, numerous studies have associated the satisfaction of the BPNs with work-related outcomes (Van den Broeck et al. 2016). With regard to the teaching context, past studies conducted with the MBI have shown that teachers, whose three BPNs have been satisfied, report less feelings of burnout (Kaplan and Madjar 2017; Van den Berghe et al. 2014) and greater job satisfaction (Collie et al. 2016; Lee and Nie 2014). Further, in a recent research study with secondary school teachers (Abós et al. 2018a), based on Farber’s burnout approach, the needs for autonomy and relatedness were negatively related to the feelings of overload and lack of development, whereas the need for competence was negatively associated with the feelings of neglect and lack of development. Overall, these results indicate that teachers’ BPN satisfaction not only fosters their human development, but it is also vital for feeling positive at work (i.e., with less burnout and high job satisfaction). Given that the satisfaction of autonomy, competence, and relatedness might help to buffer against the adversity of burnout in secondary school teachers, further studies based on Farber’s burnout approach are required.

On the other hand, it is also important to study some sociodemographic correlates that may affect teacher burnout. In this sense, manifold studies based on Maslach’s model have examined how sociodemographic and labor characteristics may affect burnout at work (e.g., Brewer and Shapard 2004; Purvanova and Muros 2010). In particular, gender, the type of school, and years of experience have been identified as some of the most relevant factors related to teacher burnout. Regarding gender, past studies have shown that female teachers experience higher emotional exhaustion than their male counterparts, while the opposite is true for feelings of cynicism (Antoniou et al. 2013; Betoret and Artiga 2010). With regard to type of school, results found are inconsistent. For example, in the study conducted by Solera et al. (2017), teachers who worked in state schools experienced greater feelings of burnout than those working in non-state schools. However, Arias-Gallegos and Jiménez-Barrios (2013) showed that when state school teachers were compared to non-state school teachers, the former experienced higher feelings of cynicism and inefficacy, while no differences were found in terms of exhaustion. Finally, teaching experience has been reported as a highly influential characteristic in the development of burnout, but results to date do not seem to be consistent, either. Whereas some studies have indicated that as teachers gain more experience, they suffer greater feelings of exhaustion, and they perceive themselves to be less efficient at work (e.g., Betoret and Artiga 2010), others have found opposite results (e.g., Fisher 2011; Lau et al. 2005). Integrating both results, these studies seem to suggest an inverted U relationship between teaching experience and burnout. Hence, further research on differences in burnout in terms of gender, type of school, and teaching experience is warranted, not only to identify the groups that have a greater risk of suffering one of these three burnout subtypes, but also to design more effective burnout prevention strategies.

Furthermore, research in the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on the burnout subtypes operationalized by Montero-Marín and colleagues (Montero-Marín and García-Campayo 2010; Montero-Marín et al. 2009, 2011b, c) is quite scarce. To date, and to the authors’ knowledge, only one study has examined the differences in the prevalence of burnout subtypes in university workers in terms of gender and work experience (Montero-Marín et al. 2011a). This abovementioned study showed that males have greater feelings of lack of development than females, whereas no differences were found between genders in overload and neglect. In terms of work experience, the most experienced workers suffer from greater feelings of neglect than novice workers, whereas no differences were found between them in terms of overload and lack of development. Given the limited number of studies based on Farber’s burnout approach and sociodemographic characteristics, further studies on secondary school teachers are needed to identify the groups that have a greater risk of suffering one of these three burnout subtypes.

The Present Study

Factor Structure, Composite Reliability, and Nomological Validity of the BCSQ-12 in Teachers

The aim of this study was to analyze the factor structure, composite reliability, and nomological validity of the BCSQ-12 in secondary school teachers. The three-factor structure (i.e., overload, lack of development, and neglect) of BCSQ-12 has been previously validated in university workers (Montero-Marín et al. 2011c), dental students (Montero-Marín et al. 2011b), and primary care physicians (Montero-Marín et al. 2015) via Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) procedures. For decades, EFA and CFA have been considered appropriate to study the psychometric properties of measurement instruments. However, whereas EFA models are suitable for a preliminary exploratory step, their inclusion in predictive models is not allowed (Ferrando and Lorenzo-Seva 2014). Similarly, in CFA models, cross-loadings between items and non-target factors are fixed at zero, which may cause biased estimates of factor correlations (Asparouhov et al. 2015).

To overcome these methodological limitations, together with CFA, an exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) was conducted in the present study to reinvestigate the factor structure of the BCSQ-12 in teachers. ESEM is based on integrating classical EFA with CFA procedures, providing methodological advances for EFA models that were limited to CFA and SEM models (e.g., goodness-of-fit assessment, nomological validity; Asparouhov and Muthén 2009). Further, ESEM provides methodological advances for CFA models by using oblique target rotation, which permits, not only the estimation of models in a confirmatory way, but also the free estimation of all cross-loadings between items and non-target factors (Asparouhov and Muthén 2009). Yet, it is important to note that ESEM may not always be the best solution to examine the factor structure of an instrument, and it may present some limitations. Given that CFA produces more parsimonious models, when the ESEM model does not fit significantly better than the CFA model, and does not report smaller factor correlations (i.e., the inclusion of cross-loadings in ESEM, although minimal, tends to reduce the correlations between latent factors), the CFA solution would be more suitable (Marsh et al. 2014). In addition, ESEM models commonly need larger sample sizes than CFA to maintain precision when they are conducted. Finally, despite this seemingly being a less important detail, the truth is that ESEM research has been growing in recent years and, therefore, it has less research background and evidence than CFA (Joshanloo and Lamers 2016). The combination of ESEM and CFA models can provide help to obtain a broader view of the examined construct (i.e., Farber’s burnout subtypes). Consequently, based on both the ESEM and CFA models, the first hypothesis suggests that a three-factor structure (i.e., overload, lack of development, and neglect) would emerge for secondary teachers’ responses to the BCSQ-12, showing acceptable psychometric properties.

Another important step in the validation process of an instrument is to examine its association with theoretically related constructs (i.e., nomological validity). So, according to SDT (Ryan and Deci 2017) and past studies in teachers (e.g., Abós et al. 2018a; Collie et al. 2016; Van den Berghe et al. 2014), the second hypothesis suggests that autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction will show negative relationships with burnout subtypes, and positive relationships with job satisfaction. Teachers’ job satisfaction (i.e., a positive work-related outcome), included in the study, may even help to prove if both types of work-related outcomes (job satisfaction and burnout), according to SDT, are inversely related to their psychosocial antecedents of autonomy, competence, and relatedness satisfaction (i.e., job satisfaction in a positive way, whilst burnout subtypes are so in a negative way).

Gender, Type of School, and Work Experience Differences in Teacher Burnout

A secondary aim of this study was to examine the possible differences in burnout subtypes (i.e., overload, lack of development, and neglect) depending on teachers’ gender, type of school, and teaching experience. Given that, to date, only one study has examined the differences in prevalence of burnout subtypes in university workers in terms of gender and work experience following Farber’s burnout subtype model (Montero-Marín et al. 2011a), our third hypothesis is tentative. However, previous studies have noted associations between different burnout models, which could be helpful to drive our hypotheses. In this sense, individuals experience overload when they attempt to increase their rewards by taking on an amount of work that becomes notably excessive (Montero-Marín et al. 2009). This feeling comprises a classic etiological burnout factor (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004), which in previous research conducted with the BCSQ showed an association with exhaustion (Montero-Marín et al. 2012, 2011c). Likewise, individuals who experience feelings of lack of development balance rewards by conducting tasks superficially, giving rise to feelings of meaninglessness in the workplace (Montero-Marín et al. 2009). These job feelings may trigger a negative assessment, comprising a risk factor for negative outcomes such as boredom or indifference (Montero-Marín et al. 2012), which are very close to Maslach’s burnout dimension of cynicism (Montero-Marín et al. 2012; Montero-Marín et al. 2011c). Finally, the neglect subtype optimizes rewards by reducing efforts as a consequence of the defenselessness learned at work (Montero-Marín et al. 2009). These feelings, which characterize the neglect subtype, are relatively close to Maslach’s dimension of lack of efficacy at the workplace (Montero-Marín et al. 2012; Montero-Marín et al. 2011c). Considering these associations, and also taking into account past studies conducted with Farber’s proposal (Montero-Marín et al. 2011a) and Maslach’s model (e.g., Antoniou et al. 2013; Arias-Gallegos and Jiménez-Barrios 2013; Betoret and Artiga 2010; Solera et al. 2017), we would expect to find that: (a) male teachers would obtain less feelings of overload and greater feelings of lack of development; (b) teachers with more teaching experience would obtain higher levels of neglect than teachers with less experience. Regarding type of school, no hypotheses have been formulated given the inconsistent results found in previous studies.

Methods

Ethical Disclosure

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Aragon (CEICA; PI15/0283). The database related to the first sample of 584 teachers comes from a Spanish national research project (EDU2013–42048-R). The main variables included in the initial protocol of this project were: teachers’ motivating style, motivational regulations, basic psychological needs, job satisfaction, engagement, and burnout subtypes. Given the limited instruments available in Spanish language, the main aim of this project was to provide to the scientific community with reliable and valid questionnaires to assess this psychological and work-related outcomes among secondary education teachers. Therefore, in order to better address the validations, and given the need to differentiate varied theoretical frameworks and gaps, it was decided to validate these questionnaires separately. The Basic Psychological Needs at Work Scale (Abós et al. 2018a), the Motivation for Teaching Scale (Abós et al. 2018b), and the Need-Supportive Teaching Style Scale (NSTSS) (Abós et al. 2018c) have been previously validated with this sample of 584 teachers. Therefore, this study represents the fourth and final validation study of the aforementioned project. Although it must be acknowledged that these four abovementioned studies have the same sample, it is also true that the nomological validation has been tested in all scales with different variables or even different subsamples. In this sense, the risk of error as a result of partial reports (including errors type I and II) was controlled in the present study by recruiting and using a different and complementary sample (i.e., a second sample of 106 teachers) to address the causal relationships between variables. Finally, it is also important to note that none of the results of this study have been published or presented previously in other studies.

Participants and Procedure

The study was conducted by using two totally differentiated samples of secondary school teachers from the Aragon region (northeast of Spain). Initially, all secondary school teachers (i.e., 7418) working in the Aragon region were invited to participate in the study. The response rate was 8%, resulting in an intentional sample of 584 teachers who completed the BCSQ-12 with their age, gender, type of school, and teaching experience. The average age of these teachers was 45.05 (SD = 8.97) years old, representing a wide range of ages from 25 to 66 years old. Likewise, they had been working as teachers for an average of 17.55 (SD = 10.26) years, ranging from 1 to 45 years’ teaching experience. Both genders were also well represented, resulting in 43.4% of male teachers and 56.6% of female teachers. Further, these teachers worked in 106 different secondary schools (81 state schools and 25 non-state schools). Seventy-one percent of the teachers worked in state schools whereas the rest of the teachers worked in non-state schools. Of the total of all secondary school teachers working in the region of Aragon (i.e., 7417), 3231 (i.e., 43.1%) were males and 4186 (i.e., 56.9%) females; 5279 (i.e., 71.1%) worked in state schools and 2138 (29.9%) worked in non-state schools. In this sense, gender and type of school percentages for this sample (i.e., n = 584) were proportionally equal to the total population of secondary teachers of the region of Aragon. These data statistics were provided by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (for a detailed examination, see http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/servicios-al-ciudadano-mecd/estadisticas/educacion/no-universitaria/profesorado/estadistica.html).

Furthermore, a second convenience sample of 216 different secondary school teachers, working in two state secondary schools and who did not participate in the first sample, were invited to take part in the study. The response rate was 49%, resulting in a second different intentional sample of 106 teachers who not only completed the BCSQ-12 and sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, type of school, and teaching experience), but also filled out validated questionnaires for BPNs and job satisfaction to test the nomological validity of BCSQ-12. This sample also represented a wide variety of ages (from 25 to 64 years old; Mage = 45.50, SD = 8.80), as well as a wide range of teaching experience (from 2 to 36 years old; M = 20.81, SD = 10.72). In addition, the percentage of males (41%) and females (59%) of this second convenience sample was similar to the previous sample (i.e., n = 584), and to the proportion of secondary teachers of the region of Aragon, equitably representing both genders.

In both data compilations, participants received an explanation of the study goals and a link to access the online questionnaire via e-mail. To start to fill out the questionnaire, teachers had to enter a personal code comprising the first two letters of their surnames and the first two numbers of their Identity Cards (ID). This form of identification allowed verifying that the first and the second sample were totally different. The time to fill out and submit the questionnaires was 30 days in both samples. Participation was also voluntary, and anonymity was guaranteed in both samples. Nevertheless, compared to the first sample, it also seems important to note that the two secondary schools of the second sample were chosen for convenience reasons. These two secondary schools were relatively close to the university and both were willing to collaborate with the research group, which helped to encourage -but not force- teachers to complete the online questionnaires. Therefore, although the recruitment procedures were the same (i.e., contact via email, 30 days to fill it out), these abovementioned reasons could justify the difference in response rates between samples.

Measures

The Short Version of the Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire

The Spanish short-version of the Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire (BCSQ-12; for further information, see Montero-Marín et al. 2011c) was used to assess teacher burnout. This scale includes 12 items (four items per factor) and taps into overload (e.g., “I risk my health when I pursue good results in my work”), lack of development (e.g., “I feel that my work is an obstacle to the development of my abilities”), and neglect (e.g., “When things at work don’t turn out as well as they should, I stop trying”). Responses were registered on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). This questionnaire has shown adequate reliability and validity in past research with other working populations (Montero-Marín et al. 2015).

Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction

The Spanish version of the Basic Psychological Needs at Work Scale (Abós et al. 2018a) was used to measure teachers’ BPN satisfaction. This scale includes 12 items (four items per factor) and taps into autonomy satisfaction (e.g., “My work allows me to make decisions”), competence satisfaction (e.g., “I have the ability to do my work well”), and relatedness satisfaction (e.g., “When I’m with the people from my work environment, I feel heard”). Responses were registered on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”). This scale has shown adequate reliability and validity in prior research with teachers (e.g., Desrumaux et al. 2015). In the present study, a CFA (n = 106) was performed showing adequate goodness-of-fit (χ2/df = 1.26, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.050; SRMR = 0.071; CFI = 0.973; TLI = 0.964). The composite reliability analysis obtained omega (ω) values of .93 for autonomy, .91 for competence, and .89 for relatedness, respectively.

Job Satisfaction

A Spanish translation of the Teacher Job Satisfaction Scale (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2011) was used to measure job satisfaction. This four-item scale is comprised of a single factor (e.g., “Working as a teacher is extremely rewarding”). Responses were given on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 6 (“strongly agree”). Evidence of reliability has been shown for this scale in prior research (e.g., Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2014). In the present study, a CFA (n = 106) was performed showing adequate goodness-of-fit (χ2/df = 1.04, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.021; SRMR = 0.005; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99). Omega (ω) value for the scale was .92. The four items were translated from English to Spanish using the procedures of the International Test Commission (Muñiz et al. 2013).

Gender, Type of School, and Teaching Experience

Teachers’ gender, type of school, and teaching experience were measured as categorical variables. Gender was divided into males and females, and type of school was divided into state and non-state schools. Teaching experience was transformed into three categorical variables following the classification of previous studies (Montero-Marín et al. 2011a). Teachers with less than four years’ experience were called “novice”, those between five and 16 years, “medium-experienced”, and those who had more than 16 years’ experience, “experienced”.

Data Analysis

Model Estimation

The descriptive statistics were calculated with SPSS 20. ESEM, CFA, and structural equation modeling (SEM) were performed with Mplus 7.4, and estimated with the Robust Maximum Likelihood (MLR) method, which provides standard errors and tests of model fit that are robust to the non-normality distribution of the data. MLR estimator is also preferred for Likert scales that include five or more answer categories (Rhemtulla et al. 2012). In ESEM, all main loadings were freely estimated, whereas cross-loadings were targeted, but not forced, via oblique target rotation procedure to be as close to zero as possible (Morin et al. 2016b). As per typical CFA specification, items only loaded on their respective factor, cross-loadings were constrained to zero and all three factors were allowed to correlate (Morin et al. 2016a). The standardized factor loadings (λ) and uniqueness terms (δ) of each item were reported for ESEM and CFA models.

The scale score reliability estimates were computed using McDonald’s (1970) ω = (Σ|λi|)2/([Σ|λi|]2 + Σδii). Standardized factor loadings are represented for λi and standardized item uniquenesses for δii. In contrast to Cronbach’s alpha (α), omega (ω) coefficient has the benefit of taking the strength of association between items and constructs (λi) into account, as well as item-specific measurement errors (δii) (Dunn et al. 2014). Furthermore, a vast body of studies in social sciences has offered considerable support to the use of this reliability parameter (e.g., León et al. 2015). However, because Cronbach’s alpha has traditionally been used to assess the internal consistency reliability of the factors, and it has been broadly used in educational and psychological research (Dunn et al. 2014), this coefficient was also reported for the BCSQ-12.

Nomological Validity

To test the nomological validity of the BCSQ-12, a SEM was conducted, using the most optimal model and adding latent CFA factors representing BPNs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness), and job satisfaction. Standardized regression weights (β) and explained variance (R2) were reported.

Gender, Type of School, and Experience Differences in Teacher Burnout

We conducted three multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) to examine differences in the three burnout subtypes (i.e., overload, lack of development, and neglect) using teachers’ gender, type of school, and teaching experience as independent variables. If significant differences were found, post-hoc tests were performed by means of Bonferroni’s method. Effect size (Partial Eta Square; ηp2) was reported. Values of effect size above .01 were considered small, above .06 moderate, and above .14 large (Cohen 1988). Observed power (op) was also reported for each MANOVA.

Model Assessment

Model assessment (ESEM, CFA, and SEM) was based on the following goodness-of-fit indices: comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Higher values of 0.90 and 0.95 for CFI and TLI indicate adequate and excellent fit indices, respectively (Marsh et al. 2004). Values of 0.08 and 0.06 or less for RMSEA and SRMR are considered as adequate and excellent, respectively (Marsh et al. 2004). The chi-square test (χ2), although reported, was not a decisive index in the evaluation of the models because it can be overpowered due to sample size.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

BCSQ-12 Factor Structure (Aim 1)

The results based on descriptive statistics (M and SD, n = 584) for teachers’ responses to BCSQ-12 are reported in Table 1. Correlations showed significant and strong relationships between items of the same factor. Items belonging to the overload factor showed significant and moderate-to-low relationships with the lack of development items, whereas the majority of relationships with the neglect items were non-significant. Lack of development items showed significant and moderate relationships with the neglect items.

The goodness-of-fit indices of the estimated alternative measurement models are reported in Table 2 (n = 584). The three-factor ESEM and CFA models showed similarities and an excellent level of fit in all indices (CFI and TLI ≥ 0.950; RMSEA and SRMR≤0.060). At first sight, despite the CFA model not providing a higher level of fit than the ESEM model, the similarities between the goodness-of-fit indices of both models suggest that the use of CFA could be preferable to the use of the ESEM in the BSCQ-12, considering differences in parsimony (i.e., ESEM is less parsimonious than CFA). However, the comparison of goodness-of-fit indices may not be sufficient to choose the most optimal model, needing to be complemented with a comparison of parameter estimates (Morin et al. 2016a).

Factor loadings, (λ) uniquenesses (δ), and composite reliability (ω) of the three-factor ESEM and the three-factor CFA models are reported in Table 3 (n = 584). First, the three-factor ESEM model showed significant and very high factor loadings in all items. One advantage of the use of ESEM is that it allows us to observe that the cross-loadings were not higher than 0.10 in any of the three burnout subtypes. Importantly, only seven out of 24 cross-loadings were significant, although very low. Comparing the loading factors and the cross-loadings, we observed how the overload factor appeared to be globally well-defined by high factor loadings (λ = 0.73–0.86; M = 0.80; p < 0.01) and reasonably low cross-loadings (|λ| = 0.00–0.03; M = 0.01). In addition, the four items belonging to the overload factor did not show significant cross-loadings in the remaining factors. With respect to lack of development factor loadings (λ = 0.64–0.95; M = 0.82; p < 0.01), the results were similar to overload. Cross-loadings also obtained low values (|λ| = 0.02–0.10; M = 0.06), but items five (|λOverload| = −0.04; |λNeglect| = −0.09), six (|λOverload| = 0.05; |λNeglect| = 0.08), and seven (|λNeglect| = 0.10) showed significant cross-loadings in other factors. However, comparing these values with the factor loadings, the cross-loadings can be considered notably weak. Finally, the neglect factor revealed significant and high factor loadings (λ = 0.72–0.88; M = 0.82; p < 0.01), and reasonably weak cross-loadings (|λ| = 0.01–0.05; M = 0.02). Consistent with this result, only items 11 (|λOverload| = −0.05) and 12 (|λOverload| = 0.05) showed significant values in other factors, although both obtained very low values. Second, consistent with the three-factor ESEM results, all the factors in the three-factor CFA model were well-defined, indicating significant and very high factor loadings (λ = 0.70–0.90; M = 0.81; p < 0.01). More precisely, the three burnout subtypes of overload (λ = 0.73–0.87; M = 0.80; p < 0.01), lack of development (λ = 0.70–0.92; M = 0.83; p < 0.01), and neglect (λ = 0.73–0.87; M = 0.82; p < 0.01) resulted very well-defined, even indicating a slight improvement in comparison to the factor loadings showed by the three-factor ESEM model.

With regard to reliability, both the three-factor ESEM (ωOverload = 0.88, ωLack-of-development = 0.90, ωNeglect = 0.90; M = 0.89) and the three-factor CFA (ωOverload = 0.88, ωLack-of-development = 0.90, ωNeglect = 0.88; M = 0.88) models showed good to excellent composite reliability, once again reporting equal results for both approaches. In line with this observation, the internal consistencies of the BCSQ-12 were 0.88, 0.89, and 0.90 for overload, lack of development, and neglect, respectively, as indexed by Cronbach alphas. Finally, latent correlations of the ESEM and CFA solutions between the three burnout subtypes are reported at the bottom of Table 3 (n = 584), resulting in similar findings (ESEM: |r| = 0.10 to 0.54, M = 0.30; CFA: |r| = 0.09 to 0.54, M = 0.29).

Despite the ESEM solution being able to help to provide a more extensive representation, compared to the CFA solution, as it reports not only factor loadings but also cross-loadings, when both models reveal similar goodness-of-fit indices, factor loadings, factor correlations, and reliability, the CFA should be considered the most suitable solution because it is more parsimonious (Marsh et al. 2014). For this reason, the three-factor CFA model was retained to test the nomological validity of the BCSQ-12 in secondary school teachers.

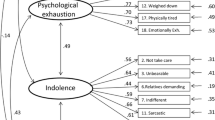

The next step to examine the psychometric properties of the BCSQ-12 in secondary teachers was to assess the nomological validity. Starting with the retained three-factor CFA model and using a different second study sample (i.e., n = 106), a SEM was conducted, resulting in the following goodness-of-fit indices: χ2/df = 1.60, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.076; 90% CI = 0.064–0.088; SRMR = 0.084; CFI = 0.978; TLI = 0.974. Although the RMSEA -considering 90% CI- and SRMR indices were slightly higher than the recommended cutoff criteria, they were close to being adequate (i.e., ≤0.080). In addition, the CFI and TLI showed excellent values. CFA factors representing autonomy, competence, relatedness satisfaction, and job satisfaction were added to the three-factor CFA model for the BCSQ-12. As observed in Fig. 1, we found that overload was only significantly and negatively related to autonomy satisfaction (ß = -0.39, p < 0.01). Further, lack of development showed similar significant and negative relationships with autonomy (ß = -0.31, p < 0.01) and relatedness satisfaction (ß = -0.35, p < 0.01). Yet, neglect showed the highest significant and negative relationship with competence satisfaction (ß = -0.42, p < 0.01), while a moderate and negative significant relationship was obtained with autonomy satisfaction (ß = -0.26, p < 0.01). Finally, job satisfaction showed an opposite significant relationship with BPNs, particularly with autonomy (ß = -0.44, p < 0.01) and competence satisfaction (ß = -0.23, p < 0.01).

Gender, Type of School, and Teaching Experience Differences in Secondary Teacher Burnout Subtypes (Aim 2)

The multivariate effects of gender (F(3, 580) = 6.647, p < .001, ηp2 = .033, op = 0.974), type of school (F(3, 580) = 18.420, p < .001, ηp2 = .087, op = 1.000), and teaching experience (F(6, 1156) = 5.879, p < .05, ηp2 = .030, op = 0.954) were significant. Univariate F-values, effect sizes (ηp2), observed power (op), and comparisons between groups based on Bonferroni’s method, in terms of gender, type of school, and teaching experience, are reported in Table 4 (n = 584). In terms of gender, female teachers reported significantly higher scores in overload than male teachers, whereas no differences were found in the other burnout subtypes. Regarding type of school, teachers who worked in state schools obtained significantly higher scores in the three burnout subtypes compared to teachers working in non-state schools. Finally, experienced teachers reported significantly higher scores in lack of development and neglect than novice teachers. Further, medium-experienced teachers also reported significantly higher scores in neglect compared to novice teachers. Overload differences between novice, medium-experienced, and experienced teachers were not found.

Discussion

It is well-established that the burnout syndrome is a serious problem, not only for teachers’ health but also for the educational system in general. Therefore, designing, implementing, and evaluating strategies to reduce and prevent teacher burnout is becoming a priority for school policymakers (von der Embse et al. 2016). However, the first step would be to validate instruments that can capture and differentiate the burnout subtypes that teachers may experience in a valid, reliable, and operational –in the sense of brief– way. Thus, taking Farber's (1990, 1991, 2000) approach, and its systematized and operationalized definition by Montero-Marín and colleagues (Montero-Marín and García-Campayo 2010, Montero-Marín et al. 2009, 2011b, c) as background, the present study examines the psychometric properties of the short version of the BCSQ and some psychological and sociodemographic correlates in secondary school teachers.

Can the BCSQ-12 Be an Appropriate Scale to Measure and Identify the Different Teacher Burnout Subtypes? (Aim 1)

The first aim of this study was to inspect the factor structure, composite reliability, and nomological validity of the BCSQ-12 in secondary school teachers. Firstly, based on the previous validation of the BCSQ-12 in university workers (Montero-Marín et al. 2011c), dental students (Montero-Marín et al. 2011b), and primary care physicians (Montero-Marín et al. 2015), the first hypothesis suggested that a three-factor structure comprised of overload, lack of development, and neglect could show acceptable psychometric properties in secondary school teachers. Consistent with the referred previous validation studies, the results of both the ESEM and CFA models indicated excellent fit indices, showing satisfactory construct validity of the three-correlated factors model of the BCSQ-12. The three-factor ESEM model showed high factor loadings with their relative latent factor. In addition, all the cross-loadings were very low and most of them were not significant, suggesting that none of the items could be loading on the other latent factors. In line with ESEM results, the three-factor CFA model also reported significant and very high factor loadings in all items, confirming the association of each item with its previously hypothesized latent factor. In addition, when cross-loadings are constrained to be zero (i.e., in the CFA model), the factor correlations can be overinflated, suggesting the potential emergence of a global dimension (Litalien et al. 2017). However, the latent correlations of the CFA model were equal to the correlations of the ESEM model, offering little support for the global burnout factor in teachers. Perfectly consistent with the theoretical proposal (Farber 1990, 1991, 2000; Montero-Marín and García-Campayo 2010; Montero-Marín et al. 2009, 2011b, c), these results suggest that the three burnout subtypes should be measured separately in teachers. This methodological combination between the ESEM and CFA models might provide a more refined picture of the three-factor structure of the BCSQ-12 in teachers. In particular, the very high factor loadings obtained in the two models, together with the low, and in some cases non-significant, cross-loadings reported in the ESEM, and consequently, the absence of overinflated factor correlations in CFA, might serve to reinforce the existence of three distinguished subtypes with which secondary school teachers may experience burnout at work. Taken together, these results may also represent a practical contribution to guide future prevention burnout studies in teachers, suggesting that prevention strategies must take the subtype of burnout experienced (i.e., overload, lack of development, and neglect) into account.

Secondly, the omega values (ω) were adequate for the three latent factors in both the three-factor CFA model and the three-factor ESEM model (ω’s ≥ 88, see Table 3) and, therefore, the first hypothesis was supported. These composite reliability results are in line with previous studies that used the BCSQ in primary healthcare professionals. In particular, Montero-Marín et al. (2016) examined composite reliability of the BCSQ-36 (and, thus, of the BCSQ-12) using a congeneric model, obtaining adequate values in the three burnout subtypes of overload (R = .81), lack of development (R = .86), and neglect (R = .86). In parallel, the present study also shows good-to-excellent Cronbach’s alpha values (α’s ≥ 88, see Table 3) in the three subtypes of burnout, providing additional support for the reliability hypothesis. Consistent with the current study, some previous validation studies of the BCSQ-12 (Montero-Marín et al. 2011b, 2011c) also reported acceptable values in the latent factors reliability based on Cronbach’s alpha. More precisely, both in the first validation with university workers (Montero-Marín et al. 2011c), and with dental students (Montero-Marín et al. 2011b), results showed good internal consistency values in terms of Cronbach’s alpha for the three burnout subtypes of overload (α = .87/.85), lack of development (α = .87/.81), and neglect (α = .85/.82). In addition, using a sample of primary healthcare professionals, Montero-Marín et al. (2016) reported good internal consistency for the three burnout subtypes of overload (R = .81), lack of development (R = .85), and neglect (R = .86), as indexed by tau-equivalent model of reliability.

The results of both reliability parameters used in the present study (i.e., omega coefficient and Cronbach’s alpha) offered good-to-excellent values for the three subtypes of BSCQ-12. In this sense, psychometric research has indicated that when the difference between Cronbach’s alpha and omega coefficients is within the range of −.20 to +20, and factor loadings are, on average, ≥.70, using one or other reliability parameter has no practical consequences (Raykov and Marcoulides 2015; Viladrich and Angulo-Brunet 2017). The present study showed that when Cronbach’s alpha was used to estimate the reliability of BCSQ-12, the degree of deviation from omega coefficient was lower than .20 in the three burnout subtypes. In fact, Cronbach’s alpha and omega values were almost the same. Likewise, the retained three-factor CFA showed factor loadings of ≥.70 in all BCSQ-12 items. These results suggest that the two reliability parameters could be adequate to guarantee the reliability of BCSQ-12 in teachers. However, it is important to bear in mind that indices obtained by Cronbach’s alpha could be biased by the number of items that comprise each latent factor as well as by the sample size (Dunn et al. 2014). In addition, in psychosocial research, questionnaires are rarely one-dimensional, and data are usually provided from different populations or samples. Consequently, the tau-equivalence assumption is also likely to be violate, which could drastically bias Cronbach’s alpha values (Dunn et al. 2014; McNeish 2018). In contrast, a good omega performance is usually achieved even when alpha assumptions are not met. Therefore, there is growing consensus in psychometric literature recommending a switch to the omega coefficient instead of alpha (Dunn et al. 2014; McNeish 2018; Revelle and Zinbarg 2009; Trizano-Hermosilla and Alvarado 2016). In this line, recent psychosocial studies have reinforced the methodological advantages of calculating the omega index (ω) (León et al. 2015; Perreira et al. 2018; Sánchez-Oliva et al. 2017). Thus, it is also important to remark the contribution of the present study in terms of composite reliability (McNeish 2018). Together with the previous composite reliability (i.e., congeneric reliability) findings, reported by Montero-Marín et al. (2016) in primary healthcare professionals, the present study also provides evidence of composite reliability -via omega values- in a different work-context (i.e., secondary school teachers) for the BCSQ-12.

Thirdly, to examine the nomological validity of BCSQ-12, a second additional hypothesis was formulated aimed at examining the relationships between BPN satisfaction, and the three burnout subtypes and job satisfaction in a different sample of 106 secondary school teachers. It is important to interpret these results with caution given the small sample size and the cross-sectional design, and also because some goodness-of-fit indices (i.e., CI 90% and SRMR) of the SEM showed scarce values. As expected, the need for autonomy showed negative relationships with the three burnout subtypes, in agreement with SDT tenets (Ryan and Deci 2017). These results seem to suggest that the design of burnout prevention strategies, based on the satisfaction of teachers’ autonomy, could be helpful to protect teachers from the three burnout subtypes. Furthermore, the competence need showed a negative relationship with the burnout subtype of neglect. This characteristic of neglect has previously been related to similar self-efficacy perceptions (Montero-Marín and García-Campayo 2010; Montero-Marín et al. 2011b). A possible explanation could be that the perception of competence satisfaction allows teachers to adapt to complex and changing environments that facilitate their teaching responsibilities when they perceive that they do not have sufficient tools to teach. However, contrary to our hypothesis, competence satisfaction did not show a relationship with overload and lack of development. The high number of tasks (e.g., preparation of lessons, assessment, meetings, or extracurricular activities) that Spanish secondary school teachers have to cope with in their work could dilute the positive effects of need for competence on the overload subtype (Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2015). Likewise, the insufficient professional development opportunities among Spanish teachers could explain the lack of relationship between teachers’ competence satisfaction and lack of development (Anaya and López 2014). According to our hypothesis, a negative relationship was found between the need for relatedness and the burnout subtype of lack of development. These results seem to suggest that prevention strategies based on the creation of warm interpersonal relationships among teachers could be helpful to prevent them focusing their attention on feelings of difficulty in making progress at work, and their intentions to change jobs. However, contrary to our expectations, associations between relatedness satisfaction with overload and neglect were not found. That is, although teachers may work in an environment that nurtures their relatedness satisfaction, they still might perceive feelings of overload. One possible explanation could be the high workload in the teaching setting, which has been widely documented as one of the most common and damaging stressors for their good psychological functioning at work (Shernoff et al. 2011; Skaalvik and Skaalvik 2015). With regard to neglect, it seems that despite having a good job climate with other teachers, these interpersonal relationships may not be determinant to the teaching style and attitude established by the teacher.

Finally, consistent with our hypothesis and previous studies (Collie et al. 2016; Lee and Nie 2014) and SDT (Ryan and Deci 2017), the autonomy and competence needs showed positive relationships with job satisfaction. Yet, the relatedness need did not show an association with job satisfaction. In line with a recent study conducted by Rothmann and Fouché (2018), these results might suggest that positive outcomes, such as job satisfaction and engagement, are more likely to occur if teachers feel competent and autonomous, while satisfying the relatedness need may not be as important as the other two BPNs to achieve positive outcomes in the teaching profession. One possible explanation could be that the need for relatedness with colleagues could be less important than the need for relatedness with students to experience teachers’ adaptive outcomes such as engagement, enjoyment, or enthusiasm (Aldrup et al. 2017; Klassen et al. 2012). Further studies are needed to refute this possible explanation. Despite this result, generally speaking, the relationships between BPN satisfaction and job satisfaction show opposite patterns compared to the three burnout subtypes. Consequently, in line with SDT (Deci and Ryan 1985, 2000, 2002; Ryan and Deci 2017), most of the relationships found in this validation study also support the nomological validity of BCSQ-12. The overall results suggest that this scale could be adequate to identify the different burnout subtypes that teachers may experience at work.

Can Teacher Burnout Be Different Depending on the Gender, Type of School, and Experience? (Aim 2)

A secondary aim of this study was to analyze the differences in the subtypes of overload, lack of development, and neglect, depending on the teachers’ gender, type of school, and teaching experience. Regarding teachers’ gender, we expected male teachers to obtain less feelings of overload and greater feelings of lack of development compared to their female counterparts. In line with our hypothesis, the results of the present study showed higher scores in overload in female teachers. According to the gender role theory (Eagly and Wood 1982), cultural reasons may explain these differences because women traditionally tend to express their feelings of fatigue at work (i.e., higher overload), while men generally do not communicate their feelings. Yet, no differences between male and female teachers were found in terms of lack of development. These results are not in line with the previous study conducted by Montero-Marín et al. (2011a), who found higher scores in lack of development in male university workers, suggesting that the role of men has always been linked to higher social expectations in terms of professional developments. In this sense, the lack of promotion opportunities among Spanish secondary school teachers, in their educational system, could explain the lack of differences between males and females in terms of lack of development in the teaching context (Vercambre et al. 2009).

With regard to type of school, considering the inconsistency found in previous studies conducted with the MBI as well as the absence of studies with Farber’s burnout approach, no hypotheses were driven. Our results showed that teachers who work in state schools report higher scores in the three burnout subtypes (i.e., overload, lack of development, and neglect) than teachers who work in non-state schools. In line with previous studies conducted in Spanish teachers (Betoret 2009; Betoret and Artiga 2010), one possible explanation is that there are more likely to be teacher stressors in state schools in Spain (e.g., higher ratio of students per classroom, higher cultural diversity of students, and higher levels of student misbehavior and amotivation). Similarly, less feelings of burnout subtypes in non-state schools teachers could be explained because non-state schools teachers may have access to a greater amount of resources (e.g., courses, materials, facilities) to improve or facilitate their teaching. Finally, we expected more experienced teachers to have greater feelings of neglect than teachers with less experience. Consistent with Montero-Marín et al. (2011a), the results of the present study showed that medium-experienced and experienced teachers have greater feelings of neglect than novice teachers. These results indicate that teaching experience may turn out to be a significant risk factor for developing a neglecting attitude at work, suggesting that neglect prevention strategies could be very useful for teachers with more years of teaching experience. Further, the results of the present study also indicated that experienced teachers reported higher scores in lack of development than novice teachers. In Spain, teachers must normally pass several public exams during the first years of their teaching careers before they get a permanent job. This fact could explain why novice teachers showed less feelings of lack of development and neglect because they still have important goals to achieve in their professional career. On the contrary, teachers who have more experience may perceive that they have fewer opportunities of professional development and challenges in their careers, giving way to negligent behaviors.

Overall, as a practical contribution, these results seem to suggest that prevention strategies to buffer the different subtypes of teacher burnout should pay special attention to high-risk groups such as females (in terms of overload), state school teachers (in terms of the three burnout subtypes), and experienced teachers (in terms of lack of development and neglect). Nevertheless, more research into Farber’s burnout subtypes and sociodemographic characteristics is necessary to produce more conclusive evidence.

Practical Implications: Specific Strategies to Prevent Teacher Burnout

Taking the recognized limitations related to nomological validity into account, but considering our results and previous studies with teachers that have evidenced the critical role of BPN satisfaction as the necessary fuel for adequate functioning at work (Klassen et al. 2012; Roth 2014), some specific prevention strategies could be useful to buffer the distress feelings of different burnout subtypes. Furthermore, this study contributes to previous literature on some sociodemographic characteristics, which could further refine future intervention studies on burnout prevention in teachers. Based on these findings and in accordance with the tenets of SDT (Deci and Ryan 1985, 2000, 2002; Ryan and Deci 2017), some practical implications for teachers themselves, but also for headteachers and the educational administration, are proposed.

Teachers who experience overload burnout risk their own health to fulfill their teaching tasks and obligations. In this sense, the results of this study could invite to rethink that prevention strategies, based on supporting teachers’ need for autonomy, may help to prevent teacher overload. In line with this claim, previous evidence (Van den Berghe et al. 2013) suggests that the educational administration could support teachers’ need for autonomy by developing a more consensual curriculum with teachers, and making higher quality resources available in classrooms to stimulate and facilitate teaching. Likewise, some actions, such as providing teachers with enough freedom in terms of their teaching style, opportunities to participate in interdisciplinary project-based learning, responsibilities in the development of their school’s educational projects or in student assessment, could be adopted by headteachers to support teachers’ need for autonomy. Importantly, consistent with the sociodemographic results found, educational administrations and headteachers should be aware that these suggested strategies could be especially important for female and state school teachers.

Teachers who experience lack of development feel that teaching provides insufficient challenges. The results of this study suggest that prevention strategies geared towards supporting teachers’ autonomy and relatedness satisfaction may provide help to try to prevent teachers’ lack of development. In this sense, in addition to the aforementioned strategies to support teacher autonomy, recent research (Durksen et al. 2017) has shown some ideas on how educational administration and headteachers could support teachers’ need for relatedness. For instance, encouraging participation in need-supportive teaching training programs and interdisciplinary projects, and promoting educational innovations could provide new challenges for teachers, but they may also strengthen relationships between teachers from different areas or courses, developing a friendly and warm environment in schools. Likewise, organizing coexistence activities (e.g., sports, recreational, or training activities) outside working hours could allow teachers to get to know their peers in other contexts. Further, it is important to add that prevention strategies that focus on lack of development could be particularly pertinent for state school and experienced teachers.

Teachers who experience neglect feel that they do not have all the desired resources in order to deal with their teaching tasks, and consequently, they do not care anymore about their responsibilities as teachers or the possible related outcomes. The results of this study invite to think that prevention strategies based on supporting the need for autonomy mentioned above and, in particular, prevention strategies based on supporting the need for competence, may help to reduce or prevent teachers’ feelings of neglect. In this sense, educational administration and headteachers could support teachers’ competence satisfaction by providing opportunities to attend conferences and by giving teachers more positive feedback. Further, training in new methodologies and technologies, which can cope with some teacher stressors (e.g., student misbehavior or amotivation), could increase their feelings of competence (Rothmann and Fouché 2018). This could be especially useful for stimulating the professional development of the more experienced teachers who commonly feel further removed from the new methodologies and technologies. In this vein, it is important to note that these neglect burnout prevention strategies could be especially useful for teachers who work in state schools, as well as for medium-experienced and experienced teachers.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are some limitations to the present study, and, therefore, results should be interpreted with caution. The first limitation is the non-representative nature of the samples investigated. Given that teachers’ participation was voluntary, some teachers that experienced high levels of burnout subtypes may, perhaps, have refused to take part of this study. A very low response rate (i.e., 8%) was obtained in the largest sample (i.e., n = 584), which could introduce bias. Regarding the second sample (i.e., n = 106), although it had a higher response rate (i.e., 49%), it has to be noted that the two secondary schools were selected by convenience. In addition, the school boards of both schools encouraged teachers to participate in the study, which could induce biased response patterns. Consequently, special caution is required when generalizing these results, particularly with the findings obtained in the nomological validity. Future research should overcome these limitations to increase the generalizability of the BCSQ-12. Likewise, participants were native speakers, which may limit their possibilities of generalization. Examining the three-factor structure of the BCSQ-12 in other teachers with different mother tongues should be considered a relevant avenue of research. Further, future research studies would explore the invariance of BCSQ-12 among teachers working in different countries. Second, to assess the ESEM model, the present study used goodness-of-fit indices derived from research conducted with CFA. Consequently, caution is required when interpreting these results. A third limitation of the present study relates to its cross-sectional design, which makes it difficult to estimate the causal effect of BCSQ-12 factors and their correlates. Future longitudinal research will be needed to further unravel the direction of the relationships examined and to shed more light on burnout subtypes. Fourth, this study only examined the associations between the BCSQ-12 dimensions, teachers’ BPNs, and their job satisfaction. Future studies should include other relevant correlates, such as teachers’ motivation, engagement at work, MBI dimensions, stress, or anxiety to continue expanding the sequence proposed in Fig. 1 and report more information about the nomological validity of BCSQ-12 in teachers. Given that other validation studies of our project (i.e., Abós et al. 2018a) have examined similar relationships to those in this study, which could induce a risk related to the multiplicity of analyses, a second sample was recruited in this study to avoid ethical conflicts. We encourage future studies to conduct broader models, including all four scales validated in our project for a further understanding of teachers’ burnout. Fifth, although the MANOVA showed significant overload differences regarding gender and type of school, as well as lack of development and neglect differences regarding teaching experience, the limited scope of these results must be recognized due to the low effect sizes that were found. In addition, given that the categorization of the teaching experience was arbitrary, results should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, further research should examine the influence of other sociodemographic characteristics, such as monthly income, contract type and duration, or familial obligations, on burnout subtypes. Altogether, it could be helpful to design and apply strategies to prevent burnout that should be individually tailored to the perceived risk of each person. Finally, both regarding BPNs and job satisfaction, the measures used to examine the nomological validity of the BCSQ-12 were obtained through self-report questionnaires. This may be attributable to response style characteristics rather than expected associations between factors, inducing a mono-method bias. Future prospective studies should add other types of measures like observations, interviews or discussion groups.

Conclusion

The results of the present study suggest that the BCSQ-12 is a valid and reliable questionnaire to measure burnout subtypes (i.e., overload, neglect, and lack of development) in secondary school teachers. These findings suggest that the three burnout subtypes, which were previously identified by Farber (1990, 1991, 2000) and systematized by Montero-Marin and colleagues (Montero-Marín and García-Campayo 2010; Montero-Marín et al. 2009, 2011b, c), should be measured separately in teachers. Further, the relationships found between BCSQ-12 subtypes and teachers’ BPN satisfaction and job satisfaction also suggest evidence of nomological validity. Finally, female teachers, state schools’ teachers, and experienced teachers might be more severely affected by the different burnout subtypes. These findings suggest the need to design and implement strategies to support the satisfaction of teachers’ basic psychological needs, which could buffer against the detrimental effects of different burnout subtypes. Given that female teachers, state school teachers, and experienced teachers seem to have a greater risk of suffering one of these three burnout subtypes, particular attention should be paid to these teachers.

References

Abós, Á., Sevil, J., Julián, J. A., Martín-Albo, J., & García-González, L. (2018a). Spanish validation of the basic psychological needs at work scale: A measure to predict teachers’ well-being in the workplace. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance, 18(2), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-017-9351-4.

Abós, Á., Sevil, J., Martín-Albo, J., Aibar, A., & García-González, L. (2018b). Validation evidence of the motivation for teaching scale in secondary education. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 21, E9. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2018.11.

Abós, Á., Sevil, J., Martín-Albo, J., Julián, J. A., & García-González, L. (2018c). An integrative framework to validate the need-supportive teaching style scale (NSTSS) in secondary teachers through exploratory structural equation modeling. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 52, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.01.001.

Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., & Lüdtke, O. (2017). Does basic need satisfaction mediate the link between stress exposure and well-being? A diary study among beginning teachers. Learning and Instruction, 50, 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.11.005.

Anaya, D., & López, E. (2014). Spanish teachers’ job satisfaction in 2012-13 and comparison with job satisfaction in 2003-04. A nationwide study. Revista de Educacion, 365(365), 96–121. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2014-365-266.

Antoniou, A. S., Ploumpi, A., & Ntalla, M. (2013). Occupational stress and professional burnout in teachers of primary and secondary education: The role of coping strategies. Psychology, 4(3), 349–355. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.43A051.

Arias-Gallegos, W. L., & Jiménez-Barrios, N. A. (2013). Síndrome de burnout en docentes de Educación Básica Regular de Arequipa. Educación, 22(42), 53–76

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2009). Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(3), 397–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903008204.

Asparouhov, T., Muthén, B., & Morin, A. J. S. (2015). Bayesian structural equation modeling with cross-loadings and residual covariances. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1561–1577. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315591075.

Betoret, F. D. (2009). Self-efficacy, school resources, job stressors and burnout among Spanish primary and secondary school teachers: A structural equation approach. Educational Psychology, 29(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410802459234.

Betoret, F. D., & Artiga, A. G. (2010). Barriers perceived by teachers at work, coping strategies, self-efficacy and burnout. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1138741600002316.

Brewer, E. W., & Shapard, L. (2004). Employee burnout: A meta-analysis of the relationship between age or years of experience. Human Resource Development Review, 3(2), 102–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484304263335.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., Perry, N. E., & Martin, A. J. (2016). Teachers’ psychological functioning in the workplace: Exploring the roles of contextual beliefs, need satisfaction, and personal characteristics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 788–799. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000088.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2271-7.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: The University of Rochester Press.

Desrumaux, P., Lapointe, D., Ntsame Sima, M., Boudrias, J. S., Savoie, A., & Brunet, L. (2015). The impact of job demands, climate, and optimism on well-being and distress at work: What are the mediating effects of basic psychological need satisfaction? Revue Europeenne de Psychologie Appliquee, 65(4), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2015.06.003.

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046.

Durksen, T. L., Klassen, R. M., & Daniels, L. M. (2017). Motivation and collaboration: The keys to a developmental framework for teachers’ professional learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TATE.2017.05.011.

Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1982). Inferred sex differences in status as a determinant of gender stereotypes about social influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(5), 915–928. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.915.

Farber, B. A. (1990). Burnout in psychotherapists: Incidence, types, and trends. Psychotherapy in Private Practice, 8(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1300/J294v08n01_07.

Farber, B. A. (1991). Symptoms and types: Worn-out, frenetic, and underchallenged teachers. In B. A. Farber (Ed.), Crisis in education. Stress and burnout in the American teacher (pp. 72–97). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Farber, B. A. (2000). Treatment strategies for different types of teacher burnout. Psychotherapy in Practice, 56(6), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200005)56:5<675::AID-JCLP8>3.0.CO;2-D.

Ferrando, P. J., & Lorenzo-Seva, U. (2014). Exploratory item factor analysis: Some additional considerations. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1170–1175. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199991.

Fisher, M. H. (2011). Factors influencing stress, burnout, and retention of secondary teachers. Current Issues in Education, 14(1), 1–37.

Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. Journal of Social Issues, 30(1), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x.

García-Carmona, M., Marín, M. D., & Aguayo, R. (2018). Burnout syndrome in secondary school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 22(1), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-9471-9.

Gil-Monte, P. (2005). El sindrome de quemarse por el trabajo (“burn- out”). Una enfermedad laboral en sociedad del bienestar. Madrid: Pirámide.

Gluschkoff, K., Elovainio, M., Kinnunen, U., Mullola, S., Hintsanen, M., Keltikangas-Järvinen, L., & Hintsa, T. (2016). Work stress, poor recovery and burnout in teachers. Occupational Medicine, 66(7), 564–570. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqw086.

Iancu, A. E., Rusu, A., Măroiu, C., Păcurar, R., & Maricuțoiu, L. P. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing teacher burnout: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9420-8.

Innstrand, S. T., Langballe, E. M., Falkum, E., & Aasland, O. G. (2011). Exploring within - and between-gender differences in burnout: 8 different occupational groups. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 84(7), 813–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0667-y.

Joshanloo, M., & Lamers, S. M. A. (2016). Reinvestigation of the factor structure of the MHC-SF in the Netherlands: Contributions of exploratory structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences, 97, 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PAID.2016.02.089.

Kaplan, H., & Madjar, N. (2017). The motivational outcomes of psychological need support among pre-Service teachers: multicultural and self-determination theory perspectives, 2, 42. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2017.00042.

Klassen, R. M., Perry, N. E., & Frenzel, A. C. (2012). Teachers’ relatedness with students: An underemphasized component of teachers’ basic psychological needs. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(1), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026253.

Klusmann, U., Richter, D., & Lüdtke, O. (2016). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion is negatively related to students’ achievement: Evidence from a large-scale assessment study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(8), 1193–1203. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000125.

Lackritz, J. R. (2004). Exploring burnout among university faculty: Incidence, performance, and demographic issues. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(7), 713–729. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TATE.2004.07.002.

Lau, P. S. Y., Yuen, M. T., & Chan, R. M. C. (2005). Do demographic characteristics make a difference to burnout among Hong Kong secondary school teachers? Social Indicators Research, 71, 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-8033-z.

Lee, A. N., & Nie, Y. (2014). Understanding teacher empowerment: Teachers’ perceptions of principal’s and immediate supervisor’s empowering behaviours, psychological empowerment and work-related outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 41, 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TATE.2014.03.006.

León, J., Núñez, J. L., & Liew, J. (2015). Self-determination and STEM education: Effects of autonomy, motivation, and self-regulated learning on high school math achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 43, 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LINDIF.2015.08.017.

Litalien, D., Morin, A. J. S., Gagné, M., Vallerand, R. J., Losier, G. F., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Evidence of a continuum structure of academic self-determination: A two-study test using a bifactor-ESEM representation of academic motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEDPSYCH.2017.06.010.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K.-T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(3), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2.

Marsh, H. W., Morin, A. J. S., Parker, P. D., & Kaur, G. (2014). Exploratory structural equation modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 85–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory manual (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, California: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc..

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Mountain View, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, Inc..

McNeish, D. (2018). Thanks coefficient alpha, we’ll take it from here. Psychological Methods, 23(3), 412–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000144.

Montero-Marín, J., & García-Campayo, J. (2010). A newer and broader definition of burnout: Validation of the “Burnout Clinical Subtype Questionnaire (BCSQ-36).” BMC Public Health, 10(1), 302. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-302.