Abstract

Delirium is seen in about one third of all sick elderly patients. As elderly inpatient admissions increase in our setting, it becomes important to understand the risk factors and predictors of delirium to better manage and prevent this disorder. A retrospective analysis of medical records of all patients 65 years and older admitted in 2009 at the Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi was performed. A pretested questionnaire was designed to obtain information on patient demographics, diagnoses, medication usage, hospital course, and complications. All patients that had a diagnosis or sub-diagnosis of delirium were reviewed for associated factors, causes, and outcomes. Data were compared between patients with and without delirium for associated factors, and outcomes. Multivariable logistic regression was performed and crude and adjusted odds ratio with 95 % confidence interval was calculated. A total of 464 charts were reviewed and 22 % were found to have delirium. Infection was the most common cause of delirium. Increasing age (AOR 1.9), prior neurological disorder (AOR 2.2), pneumonia (AOR 3.3) and urinary tract infection (AOR 3.1), psychoactive drug use (AOR 2.1), and poor functionality (AOR 5.75) were strongly associated with an increased risk of delirium. Delirium was associated with higher length of stay, and medical complication rate and increased mortality. This was a baseline study that confirmed the commonly known risk factors for delirium. Of most concern was poor functional status and psychoactive drug use in the overall patient sample. It highlighted the need for using appropriate and timely diagnostic tests to identify delirium in our elderly inpatients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Delirium is seen in about one third of all sick elderly patients (British Geriatric Society. Guidelines for prevention, diagnosis, and management of delirium in older people in hospital. Jan 2006). It is considered to be one of the major geriatric syndromes and is usually an endpoint of several pathologic processes converging to an acutely confused state. It often serves as a marker of future frailty in the elderly. Whether present at the time of admission or acquired during hospital stay, it is associated with higher morbidity and mortality, poor outcomes (Fong et al. 2009; Witlox et al. 2010), longer hospital stay and decline in functional status. (Balas et al. 2009; O’Keeffe and Lavan 1997). Various studies have cited prevalence ranging from greater than 10 % (Siddiqi et al. 2006; Korevaar et al. 2005) to 40 % (Sandberg et al. 1999; Miller 2008). Despite its high prevalence, delirium remains largely unrecognized by the emergency room,(Han et al. 2009), admitting physicians and nurses (Inouye et al. 2001). Reasons for under diagnosis are poor recognition of the clinical features of delirium and altering course (Siddiqi et al. 2006; Inouye et al. 2001; Saxena and Lawley 2009; Inouye 2006). Several risk factors for delirium have been identified (Schor et al. 1992; Elie et al. 1998) some of which are increasing age (Saxena and Lawley 2009; Guntena and Mosimannb 2010) male gender, and use of psychoactive drugs.

Other common predictors are dementia(Guntena and Mosimannb 2010), chronic depression and prior functional status (Korevaar et al. 2005). In addition to risk factors; certain precipitating factors like infections often trigger an episode of delirium in these high risk patients (Inouye and Charpentier 1996). Elderly patients undergoing non-elective surgeries are at particular risk (Saxena and Lawley 2009; Fong et al. 2009). Hip fracture is also a well-known precipitating factor, which when complicated with delirium often signifies slower recovery and increased length of hospital stay (Adunsky et al. 2003).

Up to one third of all cases of delirium may be preventable (Fong et al. 2009; Young and Inouye 2007; Adunsky et al. 2003). Risk factor identification with timely management of precipitating factors may be the most effective way to prevent this complex disorder (Mittal et al. 2010) In addition appropriate and timely mental status examination may also help identify delirium to better assess and manage such high risk elderly patients.

Research studies published in South Asia on delirium are scarce (Chrispal et al. 2010; Khurana et al. 2011; Mattoo et al. 2010). Most of these have emerged in the last few years in response to the regional rise in the elderly population. To our knowledge no studies in Pakistan have looked at delirium as a distinct entity in the elderly.

Globally, elderly patients account for 30 % or more of hospital admissions (NHSR 2007; Choon et al. 2008; Clegg and Young 2011). Although national data is not available; in our hospital about one fifth of all admissions are of patients 65 years or older. Despite lower proportions of elderly admissions, their health care provision is often compromised, as most of these elderly patients are self-paying with no formal post discharge care options. This further adds to the burden of caring for such patients in a health care system that lacks resources to care for its elderly. An estimation of delirium and risk factor identification thus becomes particularly important in our setting. We therefore conducted this study to identify the proportion, predictors, and outcomes of delirium and to compare across genders in our in-patient setting.

Methods

Study Site

The Aga Khan University Hospital a 563 bed tertiary care teaching hospital in Karachi, Pakistan was chosen as the study site to identify the proportion of patients being admitted with delirium along with its predisposing and precipitating factors.

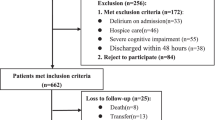

A retrospective analysis of patients admitted to Aga Khan University Hospital from January 2009 to December 2009 was conducted from November 2009 to February 2010. A total of 500 charts were reviewed and 464 were included in the study, 36 were excluded based on the eligibility criteria.

Inclusion/ Exclusion Criteria

All patients admitted to medical and surgical wards in 2009 that were 65 years and older were included in the study however patients with acutely diagnosed neurological conditions like strokes, intracranial bleeds and central nervous system infections were excluded due to primary neurologic pathology.

Patients with delirium were identified through keywords of “acute confusion”, “acute mental status changes”, “fluctuating consciousness”, “acute agitation”, “and organic brain syndrome.”

A questionnaire was designed after an extensive review of literature on delirium including its predisposing and precipitating factors. This questionnaire was further validated for its content through expert review. This was used to obtain relevant information from each patient record. Information included patient demographics, reason for admission, length of stay, admitting, and discharge diagnosis. Presence and details of co-morbids, complications, number, and name of medications used during stay were also obtained. Information regarding metabolic disturbances, infections, and memory loss were also gathered from the patient records. Presence of substance abuse, identified as use of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs was also obtained. All patient records that had a diagnosis or sub diagnosis of delirium were further reviewed to determine whether the diagnosis was established on admission or during hospital stay. Information on type of delirium: hypoactive (presenting as lethargy drowsiness with psychomotor retardation) vs. hyperactive (presenting as agitation, restlessness and hallucinations) was also obtained from patient records. Timing of mental status examination (MSE) during hospitalization was also obtained.

Approval by the University Ethics Committee was obtained prior to chart review. To maintain confidentiality, all patient records were given an identification code and the data was entered and analyzed using those codes.

Chart reviews and data collection was done by a physician with post graduate training, after undergoing a half day orientation session for chart reviews. Pilot testing of the questionnaire was conducted on 50 patient records. These charts were reviewed by two separate reviewers and information collected was shared on completion to streamline the data collection process. Ambiguous questions was reviewed and revised accordingly. Moreover 10 % of data was reviewed by two separate reviewers to ensure validity of data collected.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine sample characteristics. Mean and Standard deviations for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables were calculated. The baseline characteristics and other variables including co-morbids, complications, procedures, length of stay and functional status at discharge were compared between patients with and without delirium. For model building, delirium was taken as the dependent variable and univariate analysis was carried out to observe association with independent variables (age, gender, presence of diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, neurological disease, pneumonia or urinary tract infection, poly-pharmacy, psychoactive drug use, and functional status on admission) and crude odds ratio with 95 % CI was calculated. Independent variables were tested for multicollinearity; no correlation was found between the variables. Multivariable model was built by adding variables with p value of <0.1 obtained by the univariate analysis (all variables except presence of coronary artery disease), in order of significance and adjusted odds ratio with 95 % CI was calculated .SPSS 16.0 was used for data analysis.

Results

The results of our study showed that the mean age of patients admitted was 72.7 years (SD 6.4). One third (35 %) of these were 75 years and older. There was a slightly higher preponderance of male admission (58 %). One third of patients stayed for 5 days or longer. Analysis of co-morbids showed that the most common illnesses found in this age group were hypertension (69 %), diabetes (43 %), coronary artery disease (30 %), and neurological illnesses (13 %,) ranging from prior cerebro-vascular disease, Parkinson’s and dementia. Neurological diseases were seen more in males than females (69 % vs. 31 %, p < 0.002). A hundred and eighty-one patients (39 %) were admitted to intensive or special care units. More than half of the total charts reviewed (54 %) revealed a poor functional status at the time of admission with patients either bedridden or with restricted activities. Gender analysis showed males to be more functionally active than females (69 % vs. 31 % p value <0.001). Mental state examination (MSE) was performed on almost all patients on admission (99 %), but only on a quarter of patients during hospital stays (24 %). At the time of discharge MSE was performed in only 4 % patients. Poly-pharmacy (use of 5 or more drugs was seen in a large proportion of patients (56 %)) (Table 1). Use of alcohol and tobacco were reported by 22 % patients, more-so by males than females (86 % vs. 14 %, p < 0.001). Psychoactive medications were used by 39 % patients. Multiple psychoactive medications were used by 9 % of patients. The most prevalent usage was of benzodiazepines [n = 65 (31 %)], followed by narcotics [n = 63 (30 %)], anticonvulsants [n = 28 (13 %], antidepressants [n = 28 (13 %)], antipsychotics [n = 19 (9 %)] and antihistamine [n = 7 (3 %)].

Out of all the charts reviewed 22 % of the elderly had delirium. About half of the patients with delirium were 75 years or older with almost equal numbers of males (49 %) and females (51 %). Sub analysis of patients with delirium showed that 97 % were admitted with the diagnosis and 3 % developed it during the hospital stay. Most (73.5 %) were found to have hypoactive type, 23 % had hyperactive, and 4 % unknown type of delirium. Infection was identified as a major cause of delirium in two-thirds (69 %) of these patients, 20 % had pneumonia and 17 % had UTI. Almost half 49 % had a metabolic cause for delirium, 2 % had hip fracture. Single cause for delirium was identified in majority of patients (74 %), two causes in 22 % and three causes in 1 %. A large majority (67 %) were treated with antibiotics, 10 % with antipsychotics, and 49 % received other treatment. Almost one-fifth, 17 % of patients admitted with delirium was readmitted with delirium within the following year. MSE was performed in almost all patients with delirium (99 %) at the time of admission, 85 % during the stay but only 11 % on discharge. 59 % were admitted to SCU/ICU settings and 41 % to regular wards. Functional status on admission showed that 14 % were fully mobile, 57 % had restricted activities, and 29 % were bed ridden at the time of admission. Functional status improved on discharge in 21 % of patients who became fully mobile; in patients with restricted activities it decreased to 45 %, but the number of bed ridden patients increased to 34 %.

Univariate analysis showed that age 75 or older, female gender, pneumonia, or urinary tract infection as an admitting diagnosis, presence of hypertension, history of a prior neurological disorder, polypharmacy psychoactive drug use, and restricted activities at the time of admission were all associated with delirium (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis (Table 2) showed patients aged 75 or older were 1.9 times more likely to have delirium compared to patients less than 75 years old. Patients with prior neurological disorders were 2.2 time more likely to have delirium. Patients with pneumonia were 3.3 times and those with urinary tract infections were 3.1 more likely to become delirious. Patients using psychoactive drugs were 2.1 times more likely than non-users to develop delirium and those with restricted activities or bedridden patients were 6.2 more likely to suffer from delirium.

A greater number of patients with delirium were admitted to the intensive/special care units compared to patients without delirium (59 % vs. 33 %, p value <0.001) (Table 3).

Duration of stay was longer for patients with delirium (50 % vs. 29 %, p < 0.001). Mortality was significantly higher in patients with delirium compared to patients without delirium patients (8 % vs. 2 %, p 0.005). Medical complication rates were also higher (49 % vs. 16, p < 0.001), inpatients with delirium. Surgical and drug complication rates were the same. Higher number of consults were obtained for patients with delirium (78 % vs. 53 % p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study is the first to assess delirium in Pakistan. The noteworthy characteristics of the whole group of elderly individuals studied were the high rates of hypertension, diabetes, and poor functional status at the time of admission. Other relevant findings in this cohort were the high rates of poly-pharmacy and psychoactive drug use.

Out of the total cases reviewed, more than one-fifth of elderly patients had delirium during hospitalization. The frequency of delirium found in our study is comparable to previous studies (Siddiqi et al. 2006; Miller 2008).

Almost all elderly patients underwent a mental status examination at the time of admission. This evaluation only assessed consciousness level and orientation status. In our study, DSM IV and CAM criteria as recommended by several studies (Inouye et al. 1990; Monette et al. 2001; Kakuma et al. 2003) were not used in evaluation of delirium. Whether this assessment accurately estimated delirium in our study could not be determined. A recent systematic review (Wong et al. 2010) identified CAM testing as the best bedside tool for detection of delirium based on ease of administration and time. The term “delirium” was not used in any of the charts reviewed for our study instead it was listed by terms like acute confusion reflect a lack of awareness of delirium as a separate diagnosis.

Mental status assessment rates were also low during hospital stay and at the time of discharge. Occurrence of delirium during hospitalization and presence of persistent delirium at the time of discharge may thus have been underestimated. Persistent delirium maybe be underestimated (Levkoff et al. 1992) and can lead to poorer patient outcomes as documented in prior studies (Cole et al. 2009; Adamis et al. 2006).

Among associated factors, age more than 75 years was significantly associated with delirium. In previous studies advancing age is a well-recognized risk factor for delirium (Saxena and Lawley 2009; Schor et al. 1992; Elie et al. 1998; Guntena and Mosimannb 2010; Laurila et al. 2008) As Pakistan has joined the worldwide aging phenomena in recent years; we may see higher rates of delirium in the future years; especially in in-patient settings.

Presence of prior neurologic disease was also identified as an independent association for delirium in our elderly patients. In addition to dementia, the spectrum of neurologic conditions documented in our study included prior cerebrovascular disease and Parkinson’s Disease. However unlike other studies that have cited prior delirium (Litaker et al. 2001) and depression (Schor et al. 1992) as risk factors, these two conditions were not found in this study. It is unclear whether this was a lack of documentation or an absence of depression and prior delirium.

Both pneumonia and urinary tract infections known for precipitating delirium (Habiba et al. 2002) were also strongly associated with development of delirium in our study. Surprisingly, we only found two of the 17 patients with hip fracture to have delirium. Whether the low rate of delirium in hip fracture patients was due to a lack of recognition of delirium or because of the small number of hip fractures found during the study period was hard to ascertain.

Poor functional status was another major association identified for delirium in our study. Previous studies have also identified poor functional status as a risk factor (Korevaar et al. 2005; Laurila et al. 2008; Habiba et al. 2002). However functional status was poor in the elderly without delirium, as well. Whether poor functioning reflects the regionally high rates of musculoskeletal disease like osteoporosis (Habiba et al. 2002; Berkemeyer et al. 2009) or it is linked to the high prevalence of co-morbidities such as hypertension and diabetes via neurological and cardiovascular disease is unclear. Other factors particular to our setting such as suboptimal physical activity (Nishtar 2007) may also be contributing to poor functional as well.

Psychoactive drug use was also identified as an associated factor for delirium in this study and is in accordance with prior studies (Schor et al. 1992; Habiba et al. 2002). Unlike some previous studies however, the most commonly used psychoactive drug in our study was benzodiazepines, as opposed to narcoleptics or narcotics. This association assumes greater significance in a setting where use of psychoactive drugs is common for non-psychiatric conditions (Khuwaja et al. 2007) and self-medication is an acceptable and frequent practice.

Hypertension as a co-morbid condition was present in a significantly higher number of patients with delirium. However, due to the relatively small number of patients in our study, multivariate analysis did not identify hypertension as being independently associated with delirium. In Pakistan where one out of every three adults over 45 suffer from hypertension (World Health Organization 2011); hypertension causing delirium via neurovascular disease may be an important risk factor for delirium in our setting and further research may be needed.

Patients with delirium were also found to have longer hospital stay (Elie et al. 1998) in high intensity care areas, with greater medical complication rates, higher mortality and worse functional outcomes. Higher cost of care was identified via longer lengths of stay and greater number of consults in our study and reflects the need for early recognition of this complex disorder. Prior studies have also cited longer hospital stay and greater cost of care for such patients (Siddiqi et al. 2006; Adunsky et al. 2003). Poorer outcomes associated with delirium has been identified in other studies as well (Laurila et al. 2008; George et al. 1997) and signifies the need for prevention of delirium in high risk patients. A multi-interventional approach found to be effective in the prevention and management delirium should be considered for use in our setting, as well (Hempenius et al. 2011; O’Mahony et al. 2011).

Study Limitations

The retrospective design of the study limited the data available and may not be representative of all Pakistani patients. Follow-up and long term prognosis of patients with delirium was also not possible in this study due to its retrospective nature. Certain well known risk factors like poor vision and hearing, malnutrition and depression could not be assessed due to unavailability of data. In addition some important data on psychoactive drug usage were missing or incomplete resulting in a partial analysis.

Conclusion

This was a retrospective study that focused on an important and emerging health problem in an elderly in-patient population in Pakistan. It also gave us a glimpse of the overall health status of the elderly population in our setting. The prevalence of delirium in our analysis was comparable to the figures found in studies of Western societies. It is therefore important that all medical staff involved in the care of the elderly must be trained to recognize common risk factors to be able to prevent and effectively manage delirium. In addition, its evaluation should be done via standardized tests such as the Confusion Assessment Method. Whether modification of risk factors such as poor functional status, and psychoactive drug use will decrease delirium in our setting is yet to be determined and will require further research.

References

Adamis, D., Treloar, A., Martin, F. C., & Macdonald, A. J. (2006). Recovery and outcome of delirium in elderly medical inpatients. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 43(2), 289–298.

Adunsky, A., Levy, R., Heim, M., Mizrahi, E., & Arad, M. (2003). The unfavorable nature of preoperative delirium in elderly hip fractured patients. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 36(1), 67–74.

Balas, M. C., Happ, M. B., Yang, W., Chelluri, L., & Richmond, T. (2009). Outcomes associated with delirium in older patients in surgical ICUs. Chest, 135(1), 18–25.

Berkemeyer, S., Schumacher, J., Thiem, U., & Pientka, L. (2009). Bone T-scores and functional status: a cross-sectional study on German elderly. PloS One, 4(12), e8216.

British Geriatric Society. (2006). Guidelines for prevention, diagnosis and management of delirium in older people in hospital. (Jan 2006).

Choon, C. N., Shein, S. L., & Chan, A. (2008). Feminization of Ageing and Long term Financing in Singapore. Available at http://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/ecs/pub/wp-scape/0806.pdf.

Chrispal, A., Mathews, K. P., & Surekha, V. (2010). The clinical profile and association of delirium in geriatric patients with hip fractures in a tertiary care hospital in India. Journal of the Association of Physicians India, 58, 15-19.

Clegg, A., & Young, J. B. (2011). Which medications to avoid in people at risk of delirium: a systematic review. Age and Ageing, 40(1), 23–29.

Cole, M. G., Ciampi, A., Belzile, E., & Zhong, L. (2009). Persistent delirium in older hospital patients: a systematic review of frequency and prognosis. Age and Ageing, 38(1), 19–26.

Elie, M., Cole, M. G., Primeau, F. J., & Bellavance, F. (1998). Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 13(3), 204–212.

Fong, T. G., Tulebaev, S. R., & Inouye, S. K. (2009). Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nature Reviews Neurology, 5(4), 210–220.

George, J., Bleasdale, S., & Singleton, S. J. (1997). Causes and prognosis of delirium in elderly patients admitted to a district general hospital. Age and Ageing, 26(6), 423–427.

Guntena, A. V., & Mosimannb, U. P. (2010). Delirium upon admission to Swiss nursing homes: a cross-sectional study. Swiss Medical Weekly, 140(25–26), 376–381.

Habiba, U., Ahmad, S., & Hassan, L. (2002). Predisposition to osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons-Pakistan, 12, 297–301.

Han, J. H., Zimmerman, E. E., Cutler, N., Schnelle, J., Morandi, A., Dittus, R. S., et al. (2009). Delirium in older emergency department patients: recognition, risk factors, and psychomotor subtypes. Academic Emergency Medicine, 16(3), 193–200.

Hempenius, L., van Leeuwen, B. L., van Asselt, D. Z., Hoekstra, H. J., Wiggers, T., Slaets, J. P., et al. (2011). Structured analyses of interventions to prevent delirium. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(5), 441–450.

Inouye, S. K. (2006). Delirium in older persons. The New England Journal of Medicine, 354(11), 1157–1165.

Inouye, S. K., & Charpentier, P. A. (1996). Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. Journal of the American Medical Association, 275(11), 852–857.

Inouye, S. K., van Dyck, C. H., Alessi, C. A., Balkin, S., Siegal, A. P., & Horwitz, R. I. (1990). Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine, 113(12), 941–948.

Inouye, S. K., Foreman, M. D., Mion, L. C., Katz, K. H., & Cooney, L. M., Jr. (2001). Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161(20), 2467–2473.

Kakuma, R., du Fort, G. G., Arsenault, L., Perrault, A., Platt, R. W., Monette, J., et al. (2003). Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: effect on survival. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 51(4), 443–450.

Khurana, V., Gambhir, I. S., & Kishore, D. (2011). Evaluation of delirium in elderly: a hospital-based study. Geriatrics and Gerontology International.

Khuwaja, A. K., Ali, N. S., & Zafar, A. M. (2007). Use of psychoactive drugs among patients visiting outpatient clinics in Karachi, Pakistan. Singapore Medical Journal, 48(6), 509–513.

Korevaar, J. C., van Munster, B. C., & de Rooij, S. E. (2005). Risk factors for delirium in acutely admitted elderly patients: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatrics, 5, 6.

Laurila, J. V., Laakkonen, M. L., Tilvis, R. S., & Pitkala, K. H. (2008). Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in a frail geriatric population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 65(3), 249–254.

Levkoff, S. E., Evans, D. A., Liptzin, B., Cleary, P. D., Lipsitz, L. A., Wetle, T. T., et al. (1992). Delirium. The occurrence and persistence of symptoms among elderly hospitalized patients. Archives of Internal Medicine, 152(2), 334–340.

Litaker, D., Locala, J., Franco, K., Bronson, D. L., & Tannous, Z. (2001). Preoperative risk factors for postoperative delirium. General Hospital Psychiatry, 23(2), 84–89.

Mattoo, S. K., Grover, S., & Gupta, N. (2010). Delirium in general practice. Indian Journal of Medical Research, 131, 387–398.

Miller, M. O. (2008). Evaluation and management of delirium in hospitalized older patients. American Family Physician, 78(11), 1265–1270.

Mittal, V., Muralee, S., Williamson, D., McEnerney, N., Thomas, J., Cash, M., et al. (2010). Review: delirium in the elderly: a comprehensive review. American Journal Alzheimer’s Disease Other Dementia, 26(2), 97–109.

Monette, J., Galbaud du Fort, G., Fung, S. H., Massoud, F., Moride, Y., Arsenault, L., et al. (2001). Evaluation of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) as a screening tool for delirium in the emergency room. General Hospital Psychiatry, 23(1), 20–25.

National Health Statistics Report. (2007). National Hospital Discharge Survey. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr029.pdf.

Nishtar, S. (2007). Health Indicators of Pakistan—Gateway Paper II. Islamabad, Pakistan: Heartfile. Available at: www.heartfile.org/pdf/GWP-II.pdf.

O’Keeffe, S., & Lavan, J. (1997). The prognostic significance of delirium in older hospital patients. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 45(2), 174–178.

O’Mahony, R., Murthy, L., Akunne, A., & Young, J. (2011). Synopsis of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guideline for prevention of delirium. Annals of Internal Medicine, 154(11), 746–751.

Sandberg, O., Gustafson, Y., Brannstrom, B., & Bucht, G. (1999). Clinical profile of delirium in older patients. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 47(11), 1300–1306.

Saxena, S., & Lawley, D. (2009). Delirium in the elderly: a clinical review. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 85(1006), 405–413.

Schor, J. D., Levkoff, S. E., Lipsitz, L. A., Reilly, C. H., Cleary, P. D., Rowe, J. W., et al. (1992). Risk factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly. Journal of the American Medical Association, 267(6), 827–831.

Siddiqi, N., House, A. O., & Holmes, J. D. (2006). Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age and Ageing, 35(4), 350–364.

Witlox, J., Eurelings, L. S., de Jonghe, J. F., Kalisvaart, K. J., Eikelenboom, P., & van Gool, W. A. (2010). Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. Jama, 304(4), 443–451.

Wong, C. L., Holroyd-Leduc, J., Simel, D. L., & Straus, S. E. (2010). Does this patient have delirium?: value of bedside instruments. Jama, 304(7), 779–786.

World Health Organization. (2011). Noncommunicable country profiles 2011. Available at http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/pak_en.pdf.

Young, J., & Inouye, S. K. (2007). Delirium in older people. BMJ, 334(7598), 842–846.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sabzwari, S., Kumar, D., Bhanji, S. et al. Proportion, Predictors and Outcomes of Delirium at a Tertiary care Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. Ageing Int 39, 33–45 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-012-9152-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-012-9152-5