Abstract

There is a wave of globalized match-fixing occurring in football. In the last few years, there have been investigations and scandals in dozens of different countries in every continent. However, no academic has explored why the players agree to fix these football matches? They display few of the characteristics of normal deviancy: the athletes have high societal and sexual status. They are, purportedly, well-rewarded for their work. In previous work, it has been shown that the athletes are rarely coerced into fixing, so why would they fix matches? In this paper, the author uses both quantitative and qualitative (including interviews with some athletes) methods to show that fixing is largely the purview of older players nearing the end of their careers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since I first set my sights on Soccer as a career I have met almost every known type of football fiddle. I have been involved in quite a few myself and I am not ashamed. I, like hundreds of others, have been driven to it by the miserly attitude of the authorities in their assessment of fair payment for services rendered… You can see why we look round for alternative sources of ‘income’; why we are not above a little bribery and corruption so long as nobody gets hurt in the process. Trevor Ford, I Lead the Attack, 1957, page 20.

Introduction

“Modern sports is suffering from a cancer,” said Michel Platini, the current Head of European Football Association (UEFA), as he testified before the Council of Europe (Platini 2014). Michel Platini’s vivid imagery has been echoed by other prominent sports officials. Jacques Rogge, the former head of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), claimed that “Now there is a new danger coming up that almost all countries have been affected by and that is corruption, match-fixing and illegal gambling.” (July 2011). His successor at the IOC, Thomas Bach, upon assuming the position in 2013, declared that “fixing and corruption… are the number one problem facing sport” (Bach 2014). Sepp Blatter, the current head of FIFA (the Federation International de Futbol Associations – the group that oversees international football) has made similar claims (see Blatter 2013).

They are speaking about the “Tsunami” of match-fixing that European policeman claim has swept over international sport (Europol et al. 2013). These investigators used that word when they spoke of over six-hundred matches in 3 years being fixed. The corrupted matches ranged from relatively obscure games in, for example, the Finnish second-division to over-one-hundred-and-fifty matches in international games played by national teams. The police claimed their findings were “the tip of the iceberg”. Their work has been mirrored in over-sixty national police investigations into this phenomenon across the world: from South Korea (where they have been several suicides of athletes linked to the issue) to Australia (where in 2014, several athletes were convicted of their participation in fixed matches) to Hungary, El Salvador and South Africa (Hill 2013: Interpol 2014).

These sports officials and police investigators are speaking about the globalization of sports corruption. First revealed in ‘The Fix’ (Hill 2010) it is the linkage between corrupted athletes around the world and the large Asian-based sports gambling market. It is a relatively new method of corruption in a very old phenomenon (match-fixing was recorded at the ancient Olympics and in numerous examples in differing historical eras and sports since that time (see Hill 2013, Chapter 1). However, what is new is that a set of fixers based in Malaysia and Singapore travel the world fixing football matches (and other sporting events) using largely identical methods regardless of the country or culture of the athletes.

Estimates vary as to the exact size of the illegal sports gambling market. A 2006 study in the American journal Foreign Policy valued the entire Asian gambling industry both legal and illegal at $450 billion (U.S.) a year. In comparison, the Asian pharmaceutical industry is worth roughly $106 (U.S.) billion a year. It is difficult to know how accurate the gambling figure is or how mucho of it is spent on sports gambling. For example, the Remote Gambling Association (RGA) (a trade group that represents many of the private European bookmaking companies) claimed that the total of all gambling and betting in the world is $335 billion (U.S.) a year. However, the World Lottery Association (WLA) the umbrella-group of legal government-run gambling companies, claimed that the total amount of the illegal sports gambling world, with most of this market in Asia, is approximately $90 billion (U.S.). Other estimates have gone even higher. Interpol – the International Police Association - has announced the, largely-illegal Asian sports gambling market is worth approximately $500 billion. While a former senior executive of the sports gambling section of the Hong Kong Jockey Club estimates that the total size of the market might be as high as one trillion (U.S.) dollars (Hill 2013, 142–145).Footnote 1

The dramatic statements and large financial estimates of the Asian sports gambling industry, however, miss one particular question: at the heart of most of these fixed games are athletes who agree to take part in corruption.Footnote 2 Why would a prominent athlete participate in a gambling fix? This paper attempts to answer the specific question of motivation of corrupted athletes.

It is question that does not seem to have an easy answer using theories from classic criminology. Criminologists are fascinated with the question of why criminals commit crime (or deviancy). In 1938, Robert Merton, one of the thinkers whose ideas have shaped this field, proposed a large-scale motivation of criminals. He argued that criminal deviant acts are, largely, committed by working class males who lack status and respect in their society. The perpetrator has little or no legitimate means of acquiring that status and thus turns to a criminal pathway to gain the economic and social status that more privileged members of society can more easily acquire.Footnote 3

However, using Merton’s argument, it seems that he and his disciples would say that professional athletes are the last people to commit an act of corruption. After all, the players do a job that commands an enormous amount of status in their societies: many men, women and children adore and adulate them (MIT and Manufacturing Foundation surveys, cited by Kuper, Simon. “Pain and humiliation and fear - for a few moments of glory.” The Financial Times: London. July 23 2005). Their place of work is watched by tens of thousands of fans. They are, purportedly, well rewarded by relatively large salaries. It is difficult to think of a profession that enjoys more status in society than an elite athlete. Yet across a range of different leagues, countries and cultures, athletes at the very height of their careers and prestige have taken the decision to commit a deviant act. We have seen in previous work (Hill 2013, Chapters 10 & 11) that in most examples players are not coerced into gambling corruption, so why would so many players decide to commit match corruption?Footnote 4

Definitions

To help understand this question, a definition of the two types of match-fixing in professional football:

Arranged match-fixing

when corruptors manipulate a football match to ensure that one team wins or draws the match.

Gambling match-fixing

when corruptors manipulate a football match to profit-maximise on the gambling market.

These types of fixes differ in their organizers (corruptors), their timing, the relationship of power between the teams who are playing and even the total number of goals that is scored in each type of fix (Hill 2013, Chapters 3 & 4). These two types of fixes also differ in motivation for the players participating in the corruption.

This paper will focus exclusively on players who are engaged in the second type of match-fixing – gambling. The data from the FIF Pro survey, among others, shows that often players are coerced into corruption by their employers in Arranged match-fixing (1–20, FIF Pro 2012). The data analysed in this paper shows the way to understand why some footballers fix matches for gambling corruptors is to see them as economically-motivated criminals who choose to participate in fixing matches for a set of financial reasons. The best societal comparison of footballers is not disadvantaged working class males, but an eclectic mixture between high-level business executives and professional ballet dancers. Footnote 5

Methods

-

i).

Interviews - In 1967, Donald Cressey wrote of the difficulties of conducting research into serious or organized crime. One particular challenge that he highlighted was the inability to gain access to, and therefore interview criminals (Cressey 1967, 101–112). Almost 40 years later, Mike Maguire also writes of the “neglected art” of actually talking to criminals (Maguire 2000). He claims that it is comparatively rare for researchers to speak directly to criminals, outside of prison, concerning their motivations and methods. This is the first of the research methods used in this article: interviews with people who were not only inside the professional sub-culture of football but also had some direct experience in the deviant sub-culture of match-fixing. There were interviews with football officials and police officers who, purportedly, tried to fight against fixing; journalists who were, purportedly, investigating match-fixing;Footnote 6 referees who had been bribed or offered bribes to corrupt games; and players and coaches whose teams, or sections of teams, were fixing games. Most importantly, there were interviews with corruptors who arranged fixed-matches and players who took part in these games. Table 1, indicates the range of professions of the interview subjects:

Table 1 Interview subjects by profession

In Table 1, the first row lists the various professional categories of the interview subjects. Four of the categories are self-explanatory: referees, players, corruptors and journalists. The other four categories consist of the following groups: gamblers – any bettors, odd compliersFootnote 7 or gambling industry worker from executive to ‘runners’; officials – any league or team administrators, including coaches or managers; law enforcement – police officers, secret service personnel or state prosecutors; others contains a miscellaneous range of professions.Footnote 8

Most of the interview subjects reported that the topic of match-fixing in football is immensely controversial and that they feared recriminations from either the corruptors or the authorities if they spoke out. Because of the controversial nature of the topic almost all of the interviews were “off the record”. Particularly, people who were still serving in the game stressed that if they were to be quoted, either publicly or in such a way as to allow people to guess their identity, they would lose their job or possibly face more severe consequences.

A number of bookies and corruptors were also kind enough to share some of their time and knowledge. Their criminal “bona fides” were thoroughly checked, either through law enforcement or criminal sources or by court records, before the interviews to ensure that they were genuine match fixers. For them, the risk was extremely high, as in many jurisdictions organized gambling, let alone fixing matches, is illegal. Accordingly, the following device is used in the text: proper names are changed and all interview subjects are given a specific code. Table 2.1, row 2, lists this code. Each category has a specific code – Players = P, Referees = R, etc. – and each interview subject is given a number depending on the date of the interview. So, the first player interviewed is P1, the first corruptor COR1, and so on. The few interview subjects who did insist on being on the record are identified both by their last name and their profession: for example, Blatter, SO44, Blatter 2014 or Gregg, P23, 2005.

-

ii).

Confession Databank: The term “confession” is used loosely here. The sources are sometimes confessions given in newspaper interviews or books, but often they are covertly taped conversations or trial transcripts. The key is that the actual text of each item in the databank consists of the actual words of the person who fixed a match or took part in one. A few examples: the recorded telephone conversations of a Russian football club owner in his attempts to fix a match; the covertly taped conversations of the Belgian corruptors of the Semi-Final of the UEFA Cup of 1984; and the judicial confession of the Italian gambling corruptors who attempted to fix Serie A matches in the 1979–80 season. However, the most useful and pertinent texts were the police confessions of Malaysian-Singaporean football players from the 1995 investigation. These confessions have never been previously-publicly examined and access to them by law enforcement sources in the Malaysian-Singaporean community. They contain a rich material of primary data on how the players rigged matches and tournaments.

Another source of information were the Singapore court transcripts of eleven cases that were tried in court between 1986 and 2000 on match-fixing in football. These too contained a great deal of information that outlined methods, strategies and structures of the gambling syndicates and their relationships with various players, coaches and referees within the game. In total there were over 313,000 words: from 17 different countries and 6 international tournaments, in 10 different languages. The confession databank and transcribed interviews consists of over 560,000 words. All the databank has been completely translated – using at least two different translators for each language, to ensure accuracy – and transcribed.Footnote 9

In this way, through both qualitative interviews and text analysis of actual corruptors words, Maguire’s plea for researchers to directly speak to criminals is partially answered (Maguire 2000).

-

iii).

Databases: Finally, much of the evidence used in the book comes from the creation of several databases.Footnote 10 The two principal ones are the Fixed-Match Database (FMDB) and the Fixing/Non-Fixing Players Database (the FPD database). The FMDB was constructed by finding in newspaper articles, interviews or through the compilation of the confession databank, examples of fixed matches. The database is, currently, comprised of 301 fixed matches in 60 different countries and 55 different leagues or cup play. The FMDB consists of 39 variables. There are 11 information variables: date of match, name of team, league, etc.; 22 categorical variables, listing things like “was organized crime involved in the fix?”; “was the home team fixing?”; 2 continuous variables, e.g. total number of goals scored in the game; and 4 ordinal variables, e.g. degree of certainty of the fix.

The most important of these was how did one know that a game had actually been fixed? After all, almost every week there is some compliant from an outraged manager or a disgruntled fan that their team only lost because someone, somewhere had been “got at.” So it was necessary to be clear about how certain it was that a game was actually fixed. Accordingly, a variable was developed – degree of certainty of fix. The first, and highest, degree of certainty was if the game had been declared fixed in court or some legal proceedings. A second database, the Fixed-match Database 2 was developed (FMDB-2), where only the games that a judicial decision of some kind had ascertained that the event had been fixed was used. This is the principal database used in this book.

For each game in this database there were at least two match-reports: a statistical one, listing times of goals, number of yellow/red cards, substitutions; and an anecdotal report listing any possible missed penalties or own goals that the statistical report may have missed. Any game, where these reports could not be found was excluded from the database (there are 88 games where this information was not available), so there are 137 games in the FMDB-2 database.

The second challenge was to ensure that there was a control group built into the database. Because football games vary so greatly in terms of culture, style and era (there are fewer goals scored in the Spanish league than in the Italian league and much fewer goals scored in contemporary games than in matches 50 years ago) the games in this database were then matched with games from a control group of purportedly honestly-played games of an equivalent culture, playing style and era. For example, in the FMDB-2 database, there are 12 games from the German league in 1971 that were fixed. To match these games, 12 games were randomly selected from a presumably honest league, the Norwegian, of the same year – so the FMDB-2 consists of 137 fixed matches and 130 control matches that are specifically matched to approximate leagues of equal playing style.

There was another database used as a “control group of the control groups.” This control group consists of five European leagues – England, Scotland, France, Germany and The NetherlandsFootnote 11 from the 2005–06 season. The two control group are contrasted to ensure that the statistical patterns do actually represent a significant trend in the data. A further point is that in my construction of the database there is no implication that all the fixes that may have occurred in a league are represented. Nor are there comparisons on the rates of fixed matches between various leagues.

There is another database - the Fixing/Non-Fixing Players Database (FPD). It is composed of 117 players who either fixed matches or were approached to fix matches. This database has 30 different variables ranging from categorical variables such as, “Was the player coerced into taking part in the fix?” to informational variables such as name, team and date. The key variable in this database is whether a player agreed to take part in the fixed matches or not. There are 93 players listed who when approached agreed to fix a match and 24 players who when approached refused.

One further note, because the source of the current trend in global match-fixing is a relatively small group (60–80) of corruptors and their runners living mostly in Malaysia and Singapore it is possible to identify cross-cultural motivations among players interviews and ‘confessions’. However, one distinction should be made: leagues/competitions of high-corruption versus leagues/competitions of low-corruption. This will be explored in a further section. There are two caveats that should be made in this distinction. Many purported leagues/competitions of low corruption – ex: Germany, England, World Cup tournaments – were upon investigation shown to have some corruption (Staff 2010; Newell and Watt 2013 and Hill 2013): and secondly, the conditions in leagues/competitions change over time and are responsible for the raising or diminishing of rates of corruption: ex: English football in 2014 is markedly different from English football in 1964 (see Hill 2013, chapter 17).

Analysis

To begin with an incident that occurred during an interview with a player in Singapore.

It was the day after a Champions League game. In Asia, European games start at two or three o’clock in the morning, so after the interview we sat up most of the night to watch the game. P10 is an international player. At one time FIFA had ranked him as one of the most promising young players in the world. In the interview and conversation, he seemed very honest. He spoke about his problems adapting to a lifestyle of easy fame and status. He had become a drug addict – mostly cocaine and amphetamines – had married and then divorced, after his wife had not been able to put up with his extra-marital affairs. P10 eventually dropped out of the game for some time, and with his parents help, had tried to turn his life around. He has now re-married, is a publicly professed Christian and has re-entered football.

He had taken part in fixed matches. Key matches where the manager or owner of his team had bribed players on the opposing team. But he claimed he had never taken a bribe or had anything to do with gambling match-fixing in his life.

The next day we met for coffee. He was leaving the city that evening. He had been playing for his club for 5 months and had received no salary. The owner of the team had signed a contract with him, promising to pay him a certain amount of money each month. The owner had simply refused to do so. P10 had played on and become the team’s leading goal scorer. Still the owner had refused to pay him. Finally, the day before the interview, P10 had walked out of the club and, with his wife, was flying home.

At one point, P10 leaned forward and said, “You know a lot of these fixers don’t you?”

“Well. I have interviewed some of them, yes.”

“Give me one of their phone numbers.”

“What?”

“Give me one of their phone numbers.” He repeated. “Look, I haven’t been paid in 4 months. I have got a wife. I have got commitments. I could make a lot of money this way.”Footnote 12

**

This anecdote is included not to shock the reader or moralize, but because it seems to sum up the state of many players who consider match-fixing. In general, they take part in corrupt deals not because they are coerced, but for financial gain.

This desire for money is showed throughout an analysis of the Fixing/Non-Fixing Player Database (the FPD database). The database has 117 players who responded either yes or no to a specific invitation to fix a football match: 25 who declined, and 92 who accepted. In the database there are 24 variables. One of these variables, is “decision points” or a specific answer to a directly asked question, related to gambling-fixes – “why did you fix, or not fix, a match?” – for 76 of the players. These decision points come from varying sources in the database: some come from interviews; some are found in the equivalent of “life-histories”Footnote 13; in 23 of the cases, the players are answering this question in a court of law or a police confession.

The cases do show that the consistent, almost-universal, motivation for match-fixing is money. The precise motivation for acquiring that money varies in each case, from conditions of relative deprivation to simple greed. There are reasons like private schools or clothes for children, investment in another business or inability to sell a house, given by the players to justify their decisions. The phrases that are repeated throughout the confession databank, in both leagues of high and low corruption, are variations of this theme:

You have to understand these types. They can make more money on one fixed game than an in an entire season, they are so badly paid at these clubs they are desperate to survive… (Delepierre 2006).

It took a lot of heart-searching before I finally made up my mind to go through with the deal. I love football. It is my whole life. But I was in debt, and finding it difficult to manage. I thought of our money troubles… (Gabbert 1963a, iii)

I suppose I really decided to go “bent” because of the easy money there was to be made… (Gabbert 1964a, viii).

He had a fucking Rolex on his arm. I said, “Give it to me, I want to weigh it.” It was the fucking business – three grand’s worth of watch. He said, “This is yours, the next time you do the business [fix a match] (Grobbelaar in Thomas 2003, 93).”

In previous literature - Hill (2013, Chapters 10 & 11) – it is shown that few players are coerced into gambling match-fixing; the excerpts above show that most choose to fix matches to gain money. However, this finding leaves a series of unanswered questions unanswered: why do players accept bribes? And, which players will participate? The rest of the paper is an exploration of those two specific questions.

Is it all just anomie?

One of the most trenchant criticisms of Merton’s thinking came 20 years after his original article when the criminologist Donald Cressey in his work Epidemiology and Individual Conduct (Cressey 1960) asked a simple, but important question: “why some and not others?” In other words, it was all very well for Merton and his followers to claim that deprivation was the source of a great deal of criminal deviancy, but many poor people, who have little access to status or high paying jobs, do not turn to crime. This particular question of who commits ‘crimes’ and why - was picked up by a host of other authors, and has become one of the dominant sociological puzzles of the field, (see for example, Katz 1988 or Hoffman 2002). So following Cressey’s argument, if the main motivation for players to fix matches is financial, is it possible to come up with a set of common variables that delineate between corrupt players and non-corrupt players?

There are a range of theories that attempt to describe why some players chose to participate in gambling match-fixing. For example, the one most widely cited by Malaysian and Singaporean football officials is ‘good-young-boys-entering-into-bad-circumstances’. An idea that reflects both Durkheim's idea of anomie (Durkheim 1952, 248–250) and Merton’s ‘Strain Theory’. In the specific case of athletes, it is that they are individuals who are suddenly given so much money, status and economic opportunity that the ensuing anomie causes them to commit acts of deviancy.

This argument is, to be facetious, a version of the “sex, drugs and rock n’ roll ruining the lives of young men" argument that has assumed various guises since the Biblical prophets mentioned it to the young Israelites (see for example, Proverbs 7: 7–27 and Katz 1988, 216). The idea goes as follows: the players are young men who suddenly receive attention and financial rewards beyond their wildest dreams; they hang out with bad company, they drive fast cars, they are tempted by faster women; it all goes to their heads. Suddenly, they are fixing football matches and ruining the integrity of the sport that has given them so much. SO1, a senior Malaysian football official, outlines the structure of this argument:

Most players are dropouts. Country boys. They would probably be working in the fields or rubber estates, if it were not for football. They are completely lost when they become big football players. They visit discos. It is all new surroundings. Lots of girls. There is a lot of naiveté. They are not hard criminals … (SO1)

This lack of economic opportunity certainly describes the background of many professional football players in Malaysia and Singapore. They tend to be disproportionately from both poor backgrounds and socially marginalized groups like the Tamil community in Malaysia or the Malaysian community in Singapore (SO5).

The argument of the sports officials is strengthened by the strong sense of hierarchy in professional football in Malaysia and Singapore. The players, from their mostly disadvantaged backgrounds, are given little status within the football community. At times, they still had to kiss the hands, literarily, of some league officials. Club or league officials often do not hide their class-conscious contempt of the players. Two football officials when interviewed said, “Most of the players are sharecroppers who without football would be cutting rubber trees in the jungle…” (SO 1; SO 5).

To summarize this argument: a group of young, working class men, who normally would be unable to enjoy a middle-class lifestyle, are suddenly catapulted into a profession that gives them relatively large financial rewards but uncertain status. The players have no set of firm rules or familiar norms that can guide them in this new situation. Their state of moral confusion is so overwhelming that they commit acts of deviancy and match-fixing.

If the theory of individual anomie leading to match-fixing were correct, match-fixing would be negatively correlated with age. Because players generally enter the league between the ages of 19 and 22, then the younger a player was, the more likely he would fix matches (SO1, J9). Does the data support this hypothesis?

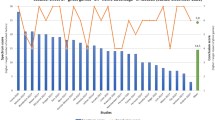

Percy Seneviratne’s history of the Malaysian football league, (written and published with the financial backing of the Football Association of Malaysia) generally supports the idea of greedy, young players losing their heads and fixing matches (Seneviratne 2000, 110–116). However, as shown below in Fig. 12.1, it also reveals that of the twenty-nine players suspended by the FAM in 1994, only five of them were twenty-four or under. The other twenty-four players were senior professionals with years of experience both as players and in enjoying “the high life.” Over fifty percent (15) of the players were in fact, over the age of twenty-nine and were thus, in football terms, extremely experienced professionals. In other words, these fifteen were the players on the teams who had the longest time to become adjusted to the supposedly exciting lifestyle of a professional footballer.

This finding is supported by the Fixing/Non-fixing Player Database for different leagues and playing eras. In the database there are 66 players who committed acts of gambling match-fixing whose ages we know. When broken down the figures of the Malaysian-Singaporean league are, roughly, replicated. They show that match-fixing is largely the purview of older players: of the players who fixed matches 12 (18.2 %) were under the age of 25; 21 (31.8 %) were between twenty-five and twenty-eight; and a further 33 (51 %) players were 29 years old and over.Footnote 14

Figure 2 shows these figures and contrasts them with the age breakdown of players in a typical league of relatively high corruption – the English Fourth Division in 1961 (Hill 2010, Chapter 9: see also Hardaker (Secretary-General of the Football Association), Hardaker and Butler 1977) - as a control group. In that league 23.8 % of the players were under 24, 56.7 % were between 24 and 29, and only 19.5 % of players were 30 and over (English Football Association 1962). Yet this last group – players 30 and over – accounts for almost forty-five percent of the match-fixing players in the database. In other words, a player 30 and over is more than twice as likely to be engaged in match-fixing as a player under the age of 25.

These findings do not, of course, mean that we can completely dismiss the theory of individual anomie. Figures 1 and 2 indicate only when the players were either caught or confessed to match-fixing, not when they started match-fixing. Players may have begun match-fixing at an earlier age because of individual anomie, but carried on fixing for other reasons. To further test the hypothesis that match-fixing is caused by youthful anomie data for 41 of the players that gives both their ages when they were caught match-fixing and when they started fixing was analyzed. The results of this analysis are shown below in Table 2:

Table 2 also does not support the hypothesis of individual anomie. The players who do match-fix had an average of 7.39 years playing before they began fixing. The average age of the players when they start to match-fix is 26.8 years old: an age where youthful anomie caused by an introduction to a new career can be presumed to have passed.Footnote 15 It is also striking to note that the average age when a player begins match-fixing is only a few months older than the average age of a player in the league. The figure seems to indicate that as a player moves into the back trajectory of his career, it is then that match-fixing begins.

Using this data we must discount the hypothesis – that match-fixing is largely the prevail of young players unused to the new lifestyle of professional football. Rather, match-fixing seems to be mostly done by players who are well-established in their careers. This paradigm makes sense along rational lines, if a match is to be fixed, it is easier for a player with the most “playing capital” to fix the match. It is the younger, less experienced players who, generally, lack playing capital, since their place on the team is uncertain, their talent is undeveloped, and their ability unknown. The confessions and interview subjects also confirm that it was the senior players on the team who were generally the most prominent in fixing matches. These senior players were the players who had the longest amount of time to become used to the “high lifestyle.”

There is one important qualification that needs to be made concerning the results above. The tables and statistics are accurate, however, they do have an underlying sample bias. The data is perforce, mostly from leagues of high corruption. The more corruption there is, the more players there will be who are fixing, the more fixing players there are from one league, the more the database will reflect situations of high corruption. However, there are four examples in the interviews and database of anomie leading to match-fixing. The examples are not related to age; rather they are linked to leagues or circumstances of low corruption. An example, from one of the corruptors who was, allegedly, able to corrupt matches in the Olympic games:

There are some players who won’t do it for money, but they will do it for women. I fixed the XXX team in 1996 against YYY at the Olympics in Atlanta. They wouldn’t do it, when I offered lots of money. They said, “No, no, no… I am praying to God…” Finally, I got this beautiful Mexican girl. I paid her $50,000 for the whole tournament. She would hang out in the lobby. She met him (the player from the XXXX team) and then went up to his room, did it [had sex] and then she proposed to him. Then I went in… “Will you do one game for me?” He said, “Yes.” And they lose to YYYY. (Cor 1)

The significance of this example, is that sexual anomie was successfully created, not against a younger player in a league/competition of high corruption, but against an older religious player in a league (the Olympics) where corruption was relatively difficult. In other words, in leagues where corruption is widely practiced, the decision to fix games seems to come from the older players on the teams without recourse to anomie. However, in leagues/competitions with little corruption, on occasion anomie can be seen as a motivation to get players, again mostly older, to fix matches. In Hill (2013, Chapters 7–9), we saw a similar trend in the data where gambling corruptors used a “fast bucks” approach in leagues of high corruption but, in leagues of low corruption, used “counterfeit intimacy” as a way to approach players.

The general, inverse relation between age and match-fixing echoes other studies in the literature on economic crime and corruption (“white collar crime”). For example, in their Yale study, (Weisburd et al. 2001) ran a number of analyses trying to establish motivating factors for deviancy among economic criminals. They looked at marriage, home ownership and rate of employment to see if they were linked with the propensity to economic deviancy. According to Weisburd and Waring, these factors were not linked to committing economic crimes. However, what was linked to economic deviancy was age: the older the person, the more likely they were to commit an economic crime like fraud or embezzlement. Or as Weisburd and Waring wrote:

… as offenders move into middle age they gain a growing awareness of time as a “diminishing, exhaustible resource” (Shover 1985, 211). Goals and aspirations change for these offenders as for other people as they get older. We suspect that such changes influence the willingness of offenders to be involved in criminality, irrespective of opportunity structures (emphasis added) and other prerequisites for offending… (Weisburd et al. 2001, 41)

The British criminologist Dick Hobbs in his book Bad Business: Professional Crime in Modern Britain (Hobbs 2003) found a similar trend in criminals that he interviewed as this typical excerpt illustrates:

Whatever you got you want more – that’s the way we all are. It’s like anything else. You start off with something, and it seems like enough… But really it’s family. When you got kids around you, you start worrying if they will be all right, and if the bills will get paid if you go away. The money don’t go as far as it used to, and you start to feel like you should be stretching out for more… You want better things – motors and a proper home, if you got kids… the risk is there, but the money was more to the point. (Professional thief quoted in Hobbs 2003, 20–21)Footnote 16

Advancing age is one of the things that makes economic crime unique. It is in direct opposition to most “street” crimes – burglary, violent crimes, rape – where youth is directly related to the criminal’s propensity to commit them. Unlike business executives whose prowess and propensity to commit crime is linked to their intellectual achievements and professional networks (Weisburd et al. 2001, 41), football players’ success is directly linked to their physical ability. (It should be noted that professional footballers effectively become “middle aged” in their sporting careers by their late twenties, and are often described as “elderly” if still playing in their thirties).

It is because of this physical factor that there is a link between match-fixing football players and professional dancers. Wainwright and Turner discovered in their study of professional ballet dancers, Just Crumbling to Bits? (Wainwright and Turner 2006), that many dancers have an acute sense of “physical capital.” In a typical excerpt a dancer says:

I retired at 38. I would say the last 3 years [I was] increasingly aware of aches that hadn’t been there in the past, and also the fact that you take a little bit longer to get over from a particular exertion… as I got older my wife would always notice when I got out of bed and creaked! (Wainwright and Turner 2006, 244)

Linked to this idea is the sense that physical ability is not only of relatively short duration, but also extraordinarily vulnerable. Harry Gregg, a successful goalkeeper of the era when match-fixing was relatively common in the English game (including on Gregg’s own team), revealed in an interview, the attitude to injured players in the Manchester United squad: “…when you get injured at Old Trafford (Manchester United), nobody will talk to you…you shouldn’t get injured. That was just the unspoken thing…” (Gregg 2005, cited in Hill, 2010).

Ian St. John, another player of that era, echoes this when he writes, in an attempt to excuse his own match-fixing, “I wish I could write a book about all the great players of my era who were put on the rubbish heap when they were injured…” (St. John Ian and Lawton James 2006, 62).

It is this sense of the vulnerability and risk of imminent injury that is seen in the “fear of falling” that Stanton Wheeler writes of in his 1988 study of the motivation of economic criminals.Footnote 17 Wheeler claims that it is not only money that motivates economic criminals but also a sense of imminent crisis or failure. A compounding factor for athletes, is that unlike other economic criminals they are generally not particularly well-educated or have other opportunities outside their sport. The FIF Pro study, compiled by the players union, speaks of this sense of failing benefits and neglected education (FIF Pro 2012). Older football players have a very strong sense that their careers may be over in the next game or practice and they need to make as much money as possible now (P6, 8).

Conclusion

In an analysis of the above data, Robert Merton and his academic followers are actually correct in describing why a player might consider accepting a bribe. Their thesis is that the athletes are under strain or anomie in the careers, the reality is that the players may not be considering their circumstances at the current moment. Nor are they thinking about trying to gain status or income, rather they are thinking about the near-future, where they may be in a situation of anomie – no career, relatively uneducated and little opportunity to maintain both the status and pay that they enjoyed as players. Given these circumstances, it then becomes a rational choice decision for the players to attempt to profit maximize by accepting corrupt deals.

This is a key finding both academically – where so little work in the field of professional athletes corruption has been undertaken – and also in discovering methods of combatting the ‘Tsunami’ of match-fixing linked to globalized sports corruption that the sports officials quoted at the beginning of this article speak about. If one can understand properly why players undertake corruption, it should be possible to take steps to properly control it.

For example, at the current moment (November 2014) FIFA, FIFPro and Interpol have joined forces in an education campaign designed to teach players the dangers of match-fixing. Much of the focus of their campaign is an ethical-based one: where players are taught that fixing is morally a bad thing to do. Leaving aside the credibility issue of a FIFA sponsored ethical campaign (see Jennings 2006: Yallop 1999), if the data in this paper is correct, then their focus is the wrong one. It is not that players do not know the correct ethical position in gambling match-fixing: it is that players have not been paid their salaries, benefits or have received no significant post-retirement education. If the organizers of similar campaigns to took this rational-choice based focus on match-fixing, we may predict that there would be a reduction in the level of gambling match-fixing.

Notes

Because Asian sports books, particularly the illegal ones do not open their finances to scrutiny it is difficult to say which of these large estimates is correct. However, the Hong Kong Jockey Club executive was quoted as saying, “FIFA boasts about $4 billion dollars at the World Cup; we in Asia have a word for the day when the market reaches $4 billion dollars, we call it – Thursday.” (Hill and Longman 2014)

This paper does not examine corruption among referees or match-officials.

Merton’s article “Social Structure and Anomie” that outlined this theory was immensely influential and, at one point, was the single most frequently cited and reprinted paper in American sociology (Cole 1975). The article and Merton’s later modifications have produced its own school of though in criminology – “Strain Theory” - and a host of modern-day disciples (see for example, Adler et al. 1995).

The neo-Marxist School of Criminology does not seem to help either when examining this question. For its proponents, like Young or Taylor, (Walton et al. 1994) criminal deviancy can, at times, be explained by “social exclusion” or a variation on Merton’s theory of disadvantaged working class youth. But again, professional football players, although mostly from the working class, are simply not excluded from society (SO1, SO5, May 2005).

Both the Singapore and English Football Associations view potentially corrupt players as directly comparable to white-collar criminals. In an internal document circulated by their disciplinary committee they specifically compare potential match-fixing players who share information with corruptors as “analogous” to stock market insider trading (Zainal, Mohamed, Ali, Mohamed and Lomri, Ali - Disciplinary Hearing. no1-3/2003, 6. Disciplinary Committee, Football Association of Singapore 2003).

‘Purportedly’ because some of the interview subjects were themselves accused of being corrupt.

An odds compiler is the person who calculates the odds that the gambling ‘book’ is made on. They usually have a great deal of experience in mathematics and are trying to achieve a ‘perfect book’ – not as generally supposed where there is a perfect prediction of who will the win match, rather a good odds compiler is trying to set the odds on a sporting event so that both sides are equally backed.

Including 2 diplomats, 3 businessmen, 2 members of the Malaysian royal family, an academic, a politician and a political dissident.

Please see the acknowledgement section for the entire list of translators and languages.

The construction of the database owes much to the advice of Johann Lambsdorff of the University of Passau and Marc Carinici of Betcapper.com. The theoretical model comes from the chapter by Michael Biggs in Making Sense of Suicide Missions (Biggs 2005).

The same information exists for the Italian league, the Serie A, but was deliberately excluded from analysis as so many matches in the league that season were shown to have been fixed.

This player was not given any information about the corruptors.

The ages of four of the players that are unknown have been excluded, and this figure does not include the Malaysian confessions that may have been included in Seneviratne’s work.

The average professional football player, generally, starts his paid employment in the years between 19 and 22 (SO1; SO5; English Football Association 1962).

Katz has other – American – criminals expressing similar views (Katz 1988, 215).

See also Wheeler et al. 1988, for a discussion of similar themes.

References

Adler, F and Laufer, W.S. (eds). The Legacy of Anomie Theory: Advances in Criminological Theory. Advances in Criminological Theory. Ed. F and Laufer Adler, W.S.(eds). Vol. 6. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 1995

Atkinson R (1998) The Life Story Interview. In: Maanen JV (ed) Qualitative research methods. Sage, London

Bach Thomas (2014) Quoted in: http://www.lawinsport.com/tag/IOC/3 and http://www.playthegame.org/news/news-articles/2007/towards-a-global-coalition-for-good-governance-in-sport/ Found November

Biggs M (2005) “Dying without killing: self-immolation 1963–2002”. In making sense of suicide missions, ed. Diego Gambetta, 173–208 and 320–324. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Blatter S (2013) Match-fixing: Cheats will never be stopped. BBC. Available online at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/0/football/21375402 7 February

Blatter Sepp (2014) Quoted in: http://www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/organisation/footballgovernance/news/newsid = 2001014/ and http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/football/article-2118642/Sepp-Blatter-warns-match-fixing-great-problem-football.html - found November.

Cole S (1975) The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. In: Coser LA (ed) In the idea of social structure. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York

Cressey D (1960) Epidemiology and individual conduct: a case from criminology. Pac Sociol Rev 3(2):47–58

Cressey D (1967) Methodological problems in the study of organized crime. Annals of the American Academy of Political Science 374:101–12

Delepierre Frederic (2006) “On M’a Proposée 200,000 Euros”: C’est Une Première. Un Joueur Approche Par La Mafia Des Paris Truques Ose Parler. Il a Refusé Le Jackpot." Le Soir, Feburary 7, 36.

Denzin N (1989) Interpretive biography. Sage, Newbury Park

Durkheim E (1952) Suicide: A study in sociology. trans. George Simpson John A. Spaulding. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London

Europol, European Police Press Conference, The Hague, Netherlands, February 6, 2013.

FIF Pro (2012) Black book: Eastern Europe – The problems professional footballers encounter: research. Hooffddorp, The Netherlands

Gabbert Michael (1963) “I Took Bribes to Let Goals Through.” The People. April 19, 1, 8–9

Gabbert Michael (1964) “Team ‘Won’ Promotion by a Fiddle.” The People. April 26: 1, 14

Hardaker A, Butler B (1977) Hardaker of the league. Pelham Books, London

Hill D (2010) ‘A Critical Mass of corruption: Why some football leagues have more match-fixing than others’, International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship. 11(3):221-235

Hill D (2010) The fix: Soccer and organized crime. Mclleland and Stewart, Toronto

Hill D (2013) The insider’s guide to match-fixing in football. Anne McDermid & Associates, Toronto

Hill D, Longman J (2014) Fixed match cast shadow over world cup. New York Times, New York

Hobbs D (2003) Bad business: Professional crime in modern Britain. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hoffman J (2002) A contextual analysis of differential association, social control, and strain theories of delinquency. Soc Forces 81(3):753–785

Interpol (2014) see http://www.goal.com/en-us/news/1786/fifa/2014/09/10/5096265/interpol-urges-football-associations-to-get-real-on-match and http://www.espn.co.uk/espn/sport/video_audio/342383.html and http://www.playthegame.org/news/news-articles/2014/interpol-effective-global-legislation-on-match-fixing-is-unlikely/ - Found November

Jennings A (2006) Foul! The secret world of FIFA: Bribes, vote rigging and ticket scandals. Harper Sport, London

Katz J (1988) Seductions of crime: Moral and sensual attractions in doing evil. Basic Books, New York

Kuper, Simon. “Pain, humiliation and fear - for a few moments of glory.” The Financial Times: London. July 23, 2005

Maguire M (2000) “Researching “Street Criminals”: A Neglected Art.”. In: Wincup E, King RD (eds) In doing research on crime and justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Newell C, Watt H (2013) “Football match-fixing: two men charged with fraud charges made following allegations of match-fixing in football matches in Britain”. Telegraph, London

Platini Michel (2014) Testimony before the Council of Europe, Strasbourg, September, 2011. http://www.uefa.org/stakeholders/european-union/index.html - found November

Seneviratne P (2000) History of football in Malaysia. PNS Publishing Sdn Bhd, Kuala Lumpur

Shover N (1985) Aging criminals. Sociological observations, 17. Sage Publications, Beverley Hills

St. John Ian and Lawton James (2006) The Saint: My Autobiography. London: Hodder & Stoughton

Staff Writer (2010) “The European Match-Fixing Trial Led by German Prosecutors has Started in Western Germany.” National Turk, Istanbul, 6 October

Thomas D (2003) Foul play: The inside story of the biggest corruption trial in British sporting history. Bantam, London

Thomas William Issac and Znaniecki Florian (1918) The Polish Peasant

Wainwright SP, Turner BS (2006) Just crumbling to bits? an exploration of the body, ageing, injury and career in classical ballet dancers. Sociology: Journal of the British Sociological Association 40(2):237–56

Walton P, Taylor I, Young J (1994) The new criminology: For a social theory of deviancy. Routledge and Paul Kegan, London

Weisburd D, Waring E, Chayet E (2001) White-Collar Crime and Criminal Careers. In: Blumstein A, Farrington D (eds) Cambridge studies in criminology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wheeler S, Mann K, Sarat A (1988) Sitting in judgement: The sentencing of white-collar criminals. Yale University Press, New Haven

Yallop D (1999) How they stole the game. Poetic Publishing, London

Acknowledgments

A great thank you to the many translators for all their time and work on the confession database. Their kindness is deeply appreciated: Kess t’Hooft, Stefan De Wachter, Riina Ristikari, Srefania Battistelli, Graziano Lolli, Andrea Patacconi, Julika Erfurt, Thomas Gerken, Franziska Telschow, Sohnke Vosgerau, Natasha Gorina, Ekaterina Korobtseva, Ekaterina Kravchenko, Svetlana Guzeev, Eugene Demchenko, Alisa Voznaya, Maria Semenova and Emre Ozcan.

A thank you as well to the two anonymous reviewers of an early draft of this paper: their comments were invaluable. Any errors or omission are the author’s fault. Also to Professors Johann Lambsdorff and Michael Biggs for their help in structuring the various databases. A big debt of gratitude to my two supervisors Anthony Heath and Diego Gambetta for their great skill in guiding this work to its completion.

Finally a thank you to the fixers/corruptors who risked so much to speak to me about their methods of work and success in their field.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, D. Jumping into Fixing. Trends Organ Crim 18, 212–228 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-014-9237-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12117-014-9237-5