Abstract

Background

Liver metastasis is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Surgical resection and systemic chemotherapy have been reported to be effective in gastric cancer with liver metastasis (GCLM). However, the best strategy for GCLM has not been established.

Methods

From May 2009 to July 2014, a consecutive series of GCLM patients in Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University were studied. Treatment strategies were evaluated with regard to different extents of metastases.

Results

A total of 163 patients were included. The overall survival was 10.1 months. Active treatment significantly prolongs the survival of GCLM patients. The overall survival time for patients with liver-limited metastases and extra-hepatic liver metastases was 11.6 mo and 8.7 mo, respectively (P = 0.012). The median survival time for liver-limited disease of H1, H2 and H3 was 14.2, 15.8, and 8.5 months, respectively (H3 vs H2, P = 0.001; H3 vs H1, P = 0.000; H1 vs H2, P = 0.900). Systemic chemotherapy was chosen as the main strategy for the ‘extensive’ patients with extra-hepatic metastases and H3 type liver-limited metastases. Patients’ survival was benefited by multi-line chemotherapy. No differences were shown between systemic chemotherapy and curative resection or palliative resection in H1 and H2 liver-limited metastases (16.0 mo vs 12.0 mo, P = 0.711; 16.0 vs 18.8 months, P = 0.654).

Conclusion

Systemic chemotherapy was the main treatment for gastric cancer patients with liver metastases. Curative resection could be considered for highly selected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A total of 989,600 new gastric cancer cases and 738,000 deaths of gastric cancer are estimated to occur every year, and over 70 % of new cases and deaths occur in developing countries [1]. Liver metastases can be found in 4–11 % of patients with gastric cancer [2–6]. And usually liver metastasis from gastric cancer is only part of the generalized metastases of the primary tumor, including peritoneal seeding, lung metastases, or extensive lymph node metastases [7–9]. The prognosis of GCLM has been reported to be poor. The 5-year survival rate is under 10 % and the median survival is only 3–5 months without effective treatments [10]. Systemic chemotherapy is a standard treatment approach for GCLM patients [11, 12]; however, surgical resection has been recently reported to prolong the survival of GCLM patients in highly selected subjects [5, 7, 13]. At present, large concurrent randomized control studies on surgical resection and systemic chemotherapy are not available. This study is to investigate different strategies for patients with GCLM.

Patients and methods

Patients

From May 2009 to July 2014, 1580 patients were diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma in Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University. Among them, patients diagnosed as gastric cancer with liver metastases were studied, which include patients with synchronous and metachronous liver metastases. Gastric cancer was confirmed histologically, and liver metastases from gastric cancer were confirmed by enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT), or liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or PET/CT, as well as the case history. Pathological confirmation of liver metastasis was not mandatory. Hepatic metastases was classified according to the General Rules for Gastric Cancer Study and Pathology in Japan [14]: H1, liver metastases limited to one lobe of the liver; H2, isolate metastases in both lobes of the liver; H3, multiple spread of metastases in both lobes of the liver.

With regard to treatments, only GCLM patients who accepted best supportive care (BSC) and active treatments (systemic chemotherapy or surgical resection) were studied. Surgical resection could be curative or palliative. Curative gastric resection refers to the absence of residual tumor with D2 lymphadenectomy as determined both macroscopically and microscopically. Palliative resection was taken with curative intent, but at least one surgery was ultimately palliative due to microscopically or macroscopically residual disease. Patients with extra-hepatic metastases and the H3 liver-limited were integrated as ‘extensive’ group, since surgical resection is not curative for these patients. The H1 and H2 patients were referred to the potentially resectable group as these patients had the chance to get a curative resection. Chemotherapy was recommended to all the patients with resection who could tolerate. The systemic chemotherapy was performed according to the NCCN guidelines. The frequently recommended chemotherapy regimens were XELOX/SOX or DS. Three-drug regimen DCF was recommended only to a small amount of patients with good PS. Irinotecan was recommended in the multiline chemotherapy if the patient had failed Oxaliplatin and Docetaxel-based regimens.

Follow-up

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis of liver metastases in both synchronous and metachronous types to death from any cause or last follow-up. All patients were assessed every 3 months. Data on patients who were alive or lost to follow-up were censored at the date of July, 2014.

Statistical analysis

The overall survival was determined by Kaplan–Meier method, and the survival differences of the different groups were defined by log rank test. The balance of baseline characteristics of different groups was tested by Chi square. Mean comparison was performed by Student’s t test. Significance was established for values of 2-tailed P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed by The SPSS software package, version19.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 163 GCLM patients were included with the median age of 63 years old (range 31–94), of which 131 (80.4 %) patients were male and 32 (19.6 %) were female. 129 (79.1 %) cases were synchronous metastatic and 34 (20.9 %) cases metachronous metastatic. 62 (38 %) patients were companied with other distant metastases beyond liver and 101 (62 %) patients were limited to liver. Liver-limited metastases patients were further classified into three groups according to the different extent of liver metastases: 45 (27.6 %) patients for H1, 30 (18.4 %) patients for H2, and 26 (16.0 %) patients for H3. Patients’ characteristics are described in Table 1. The median follow-up time was 29.0 months (95 % CI 23.4–34.6 months).

The overall survival of patients with liver metastasis from gastric cancer

The median overall survival of the 163 patients was 10.1 months (95 % CI 8.4–11.8 months, Fig. 1). Among them, 20 (12 %) patients received best supportive care (BSC) and the rest 143 (88 %) patients received active treatment (systemic chemotherapy or surgical resection). The survival median survival time of BSC was 2.8 months (95 % CI 2.5–3.1 months), significantly shorter than 12.0 months (95 % CI 9.1–14.9 months) of active treatments (P = 0.000). In this study, 69 patients were tested for Her-2, of which 15 (21.7 %) patients were positive and 54 (78.3 %) patients negative. 10 (66.7 %) of the positive patients received Herceptin combined with chemotherapy. Patients taking Herceptin had a tendency for longer median survival than those taking chemotherapy alone, but had no statistically significance possibly due to the limited number of patients (14.7 months, 95 % CI 7.3–22.1 months vs 8.9 months, 95 % CI 1.6–16.2 months, P = 0.164). The above results showed that the prognosis of GCLM was very poor and active treatments significantly prolong the overall survival time.

The overall survival was compared between the extents of metastases. In this study, 62 (38 %) patients had extra-hepatic metastases and 101 (62 %) patients had liver-limited metastases. The median survival of those with extra-hepatic metastases and liver-limited metastases was 8.7 months (95 % CI 5.6–11.8 months) and 11.6 months (95 % CI 10.0–13.2 months), respectively (P = 0.012). Liver-only GCLM patients were classified into three types: H1, liver metastases limited to one lobe of the liver; H2, isolated metastases in both lobes of the liver; H3, multiple spread of metastases in both lobes of the liver. It turned to be 45 (27.6 %) patients of H1, 30 (18.4 %) patients of H2 and 26 (16.0 %) patients of H3. The median survivals of H1, H2 and H3 were 14.2 months (95 % CI 7.7–20.7), 15.8 months (95 % CI 13.1–18.5) and 8.5 months (95 % CI 2.9–14.1), respectively (Fig. 2). Significant difference was shown between H3 and H2 or H3 and H1 (H3 vs H2, P = 0.001; H3 vs H1, P = 0.000), but no significant difference shown between H1 and H2 (P = 0.900).

Comparison of survivals in patients with different extents of liver-limited metastases. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed a significantly poor survival time in patients with H3 liver metastases than those with H1 (P = 0.000) and H2 (P = 0.001). No significant difference existed between the survivals of H1 and H2 (P = 0.900)

Systemic chemotherapy was the main treatment of ‘extensive’ patients

For those ‘extensive’ patients with extra-hepatic metastases or H3 liver-only metastases, systemic chemotherapy as the standard treatment was recommended in guidelines. Among the 88 ‘extensive’ patients, 19 (21.6 %) patients received the best supportive care, 69 (77.3 %) patients chose systemic chemotherapy and no patient had surgical resection. The median survival of patients with systemic chemotherapy and BSC was 9.4 months and 2.8 months, respectively (P = 0.000). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3, patients with multi-line chemotherapy (n = 29) had nearly twice as much the median survival as that of single-line chemotherapy (n = 31) (14.2 months vs 6.6 months, P = 0.000). The results demonstrated that regardless of extra-hepatic or H3 type hepatic-limited metastases, systemic chemotherapy was the main treatment strategy for ‘extensive’ GCLM patients, and multi-line chemotherapy should be recommended if they can tolerate.

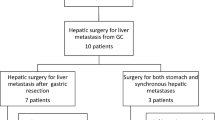

Surgical resection and systemic chemotherapy showed the similar survival time in “limited” patients

The treatment consequence for “limited” group is still controversial. In this study, H1 and H2 patients received different patterns of treatments including best supportive care (BSC), palliative resection, curative resection and systemic chemotherapy. The baseline characteristics of H1 and H2 patients are described in the supplementary material (Online Source 1, Table S1). Among the 75 ‘limited’ patients, only 1 (1.3 %) patient (H1) adopted BSC, 34 (45.3 %) patients (29 H1 + 5 H2) received curative resection, 7 (9.4 %) patients (3 H1 + 4 H2) undertook palliative resection, and 33 (44 %) patients (12 H1 + 21 H2) received systemic chemotherapy. The characteristics of patients taking different treatments are shown in Table 2. The survival time for the patient with BSC is 1.0 month which again suggested that the poor prognosis is associated with lack of active treatment. The outcomes of the three treatment strategies were analyzed. The median survivals of curative resection, palliative resection and systemic chemotherapy were 12.0 months, 18.8 months and 16.0 months, respectively, which showed no significant difference (palliative resection vs systemic chemotherapy, P = 0.654; palliative resection vs curative resection, P = 0.682; curative resection vs systemic chemotherapy, P = 0.711, Fig. 4). Along with the risks and complications brought by surgery, the results in this study suggested that systemic chemotherapy should be recommended as the main strategy in treating H1 and H2 liver-limited GCLM patients.

Comparison of survivals in H1 and H2 patients with different treatments. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed no significant difference between the survivals of palliative resection, systemic chemotherapy and curative resection (palliative resection vs systemic chemotherapy, P = 0.654; palliative resection vs curative resection, P = 0.682; curative resection vs systemic chemotherapy, P = 0.711)

Discussion

The most common site for gastric cancer to metastasize is liver. Liver metastasis was identified to be an independent prognostic factor for poor advanced gastric cancer (AGC) survival, and gastric cancer with liver metastasis (GCLM) was classified into the high risk group [15, 16]. The prognosis of GCLM is very poor as the disease is often associated with extensive metastatic lesions [17]. In this study, the median survival time of all the GCLM patients was 10.1 months, while the patients with the best supportive care were only 2.8 months. The median survival of patients with active treatment is 12.0 months. However, in the clinical practice, optimal treatments for GCLM patients have been controversial.

Systemic chemotherapy is the standard therapy recommended for Stage IV or metastatic gastric cancer by both the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines [18] and the Japanese Guidelines [19]. In the present study, most of the patients with extensive disease such as extrahepatic metastases or H3 liver-limited metastases were treated with systemic chemotherapy, which significantly prolonged their survival time compared to the best supportive care. Furthermore, the survival time for patients with multi-line chemotherapy is twice as much as with single line chemotherapy. Therefore, systemic chemotherapy was recommended as the prime treatment for this portion of patients. Multi-lines chemotherapy was encouraged.

Surgical resection was rarely applied in GCLM patients due to its generalized metastases. However, inspired by the exciting achievements by hepatic resection of colorectal cancer, we are to explore what surgical resection brings for metastatic gastric cancer. Several studies have reported that surgical resection did benefit to the survival of GCLM patients during the past few years [13, 20–23]. One of the results reported by Takemura showed that the overall survival rate of GCLM for 1, 3, and 5-year after macroscopically liver resection (R0 or R1) was 84, 50, and 37 %, respectively, and the median survival time was 34 months [13]. However, most of these studies had no control arm and limited number of long survivors was regarded as the benefit of surgical resection. It has to be noticed that in most of these studies, patients who took resection were highly selected and more favorable population than those who received systemic chemotherapy. Furthermore, in an analysis of 1452 patients who took hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonendocrine liver metastases, patients with gastric cancer experienced poor outcomes [24]. And few studies have compared the effects of surgical resection with systemic chemotherapy in the GCLM patients. In this study, curative resection seems promising for the ‘limited’ group with H1 or H2 metastases, so the survivals of curative resection, palliative resection and systemic chemotherapy in the ‘limited’ patients were analyzed. The result indicated no significant differences for the three different treatments.

So far it was reported that hepatic resection was performed only on 10–21 % of GCLM patients, but intra-hepatic recurrence happened to about 2/3 of patients [25]. The reason for high recurrence may be that about half of the hepatic metastases from gastric cancer had seeded off micrometastases, and the presence of these micrometastases was associated with a poorer result of hepatic resection [26]. Takemura reported the usefulness of repeated hepatectomy for recurrent GCLM in selected patients [27]. However, unless the patient had the recurrent lesion solitary and appropriate for curative resection, repeated hepatectomy is hard to achieve. On the other hand, surgical resection can also increase mortality and postoperative complications. Mortality was 1.1 % according to the previous studies in which the data were available, and morbidity ranged from 19 to 47 % [25]. Even in the high-experienced center, patients undertaking gastrectomy and hepatectomy usually are associated with poor quality post-operation life. Major adverse events include protracted stomach paralysis, pulmonary infection, regurgitation, malnutrition and so on.

On the contrary, systemic chemotherapy has advantage of safety and universality. As with more effective toxic drugs being explored, systemic chemotherapy seems to bring more benefit to advanced gastric cancer patients nowadays [28, 29]. And second-line or even third-line chemotherapy can still result in substantial prolongation of survival when compared to best supportive care (BSC) if physical performance permits [30]. In a study, Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy has been considered as a new standard option for patients with HER-2 positive advanced gastro-esophageal junction cancer or gastric cancer [31]. It has been reported that Her-2 positivity rate was significantly higher in liver metastasis of gastric cancer [32]. Drug resistance is wildly regarded as one of the disadvantages of chemotherapy, but new oral targeted drug like Apatinib has brought hope to chemotherapy-refractory advanced metastatic gastric cancer patients [33]. Together with the results in this study, systemic chemotherapy was recommended as the main strategy for GCLM patients even in the ‘limited’ patients.

It cannot be denied that curative resection may increase the possibility of long survivors, though the heterogeneity decreases the suitability of surgical resection in GCLM. It becomes important to determine the suitable candidates for surgical resection. It has been reported that those having solitary hepatic metastasis and the maximum diameter of hepatic lesion smaller than 5 cm seem to be benefited more [6, 13, 23, 27, 34]. In this study, among the curative resection patients, those with single liver metastasis had a longer survival than those with multiple liver metastases; however, the maximum diameter of hepatic lesion is not an independent factor for prognosis. It has also been reported that patients with metachronous hepatic metastases were better candidates for hepatic resection [2, 35]. Other reports showed no significant difference in survival between synchronous and metachronous metastases after curative resection [3]. Only one metachronous patient took curative resection in this study, and his survival was similar to the synchronous patients. Due to the limited number of metachronous patients, any conclusion concluded is not reliable.

The findings of this study indicated the importance of active treatment for GCLM patients. Systemic chemotherapy was the main treatment strategy appropriate for extensive and limited GCLM patients. Curative resection could only be considered in a small number of highly selected patients though the indications are still controversial. Randomized controlled trials are essential to evaluate the benefits of surgical resection and chemotherapy for gastric cancer patients with liver metastases; however, the patient recruitment may preclude its feasibility.

References

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90.

Okano K, Maeba T, Ishimura K, Karasawa Y, Goda F, Wakabayashi H, et al. Hepatic resection for metastatic tumors from gastric cancer. Ann Surg. 2002;235(1):86–91.

Sakamoto Y, Ohyama S, Yamamoto J, Yamada K, Seki M, Ohta K, et al. Surgical resection of liver metastases of gastric cancer: an analysis of a 17-year experience with 22 patients. Surgery. 2003;133(5):507–11.

Koga R, Yamamoto J, Ohyama S, Saiura A, Seki M, Seto Y, et al. Liver resection for metastatic gastric cancer: experience with 42 patients including eight long-term survivors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37(11):836–42.

Cheon SH, Rha SY, Jeung HC, Im CK, Kim SH, Kim HR, et al. Survival benefit of combined curative resection of the stomach (D2 resection) and liver in gastric cancer patients with liver metastases. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(6):1146–53.

Qiu JL, Deng MG, Li W, Zou RH, Li BK, Zheng Y, et al. Hepatic resection for synchronous hepatic metastasis from gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(7):694–700.

Sakamoto Y, Sano T, Shimada K, Esaki M, Saka M, Fukagawa T, et al. Favorable indications for hepatectomy in patients with liver metastasis from gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(7):534–9.

Marrelli D, Roviello F, De Stefano A, Fotia G, Giliberto C, Garosi L, et al. Risk factors for liver metastases after curative surgical procedures for gastric cancer: a prospective study of 208 patients treated with surgical resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198(1):51–8.

D’Angelica M, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Turnbull AD, Bains M, Karpeh MS. Patterns of initial recurrence in completely resected gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2004;240(5):808–16.

Jerraya H, Saidani A, Khalfallah M, Bouasker I, Nouira R, Dziri C. Management of liver metastases from gastric carcinoma: where is the evidence? Tunis Med. 2013;91(1):1–5.

Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, Takagane A, Akiya T, Takagi M, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(3):215–21.

Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H, Shirao K, Doi T, Sawaki A, et al. Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(11):1063–9.

Takemura N, Saiura A, Koga R, Arita J, Yoshioka R, Ono Y, et al. Long-term outcomes after surgical resection for gastric cancer liver metastasis: an analysis of 64 macroscopically complete resections. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2012;397(6):951–7.

Chang JC. How to differentiate neoplastic fever from infectious fever in patients with cancer: usefulness of the naproxen test. Heart Lung. 1987;16(2):122–7.

Chau I, Norman AR, Cunningham D, Waters JS, Oates J, Ross PJ. Multivariate prognostic factor analysis in locally advanced and metastatic esophago-gastric cancer−pooled analysis from three multicenter, randomized, controlled trials using individual patient data. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(12):2395–403.

Chau I, Ashley S, Cunningham D. Validation of the Royal Marsden hospital prognostic index in advanced esophagogastric cancer using individual patient data from the REAL 2 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(19):e3–4.

Hwang JE, Kim SH, Jin J, Hong JY, Kim MJ, Jung SH, et al. Combination of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation and systemic chemotherapy are effective treatment modalities for metachronous liver metastases from gastric cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2014;31(1):25–32.

Ajani JA, Barthel JS, Bekaii-Saab T, Bentrem DJ, D’Amico TA, Das P, et al. Gastric cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(4):378–409.

Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. [Journal Article; Practice Guideline]. 2011 2011-06-01;14(2):113–23.

Kerkar SP, Kemp CD, Avital I. Liver resections in metastatic gastric cancer. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12(9):589–96.

Makino H, Kunisaki C, Izumisawa Y, Tokuhisa M, Oshima T, Nagano Y, et al. Indication for hepatic resection in the treatment of liver metastasis from gastric cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(6):2367–76.

Tiberio GA, Coniglio A, Marchet A, Marrelli D, Giacopuzzi S, Baiocchi L, et al. Metachronous hepatic metastases from gastric carcinoma: a multicentric survey. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35(5):486–91.

Ueda K, Iwahashi M, Nakamori M, Nakamura M, Naka T, Ishida K, et al. Analysis of the prognostic factors and evaluation of surgical treatment for synchronous liver metastases from gastric cancer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394(4):647–53.

Adam R, Chiche L, Aloia T, Elias D, Salmon R, Rivoire M, et al. Hepatic resection for noncolorectal nonendocrine liver metastases: analysis of 1,452 patients and development of a prognostic model. Ann Surg. 2006;244(4):524–35.

Kodera Y, Fujitani K, Fukushima N, Ito S, Muro K, Ohashi N, et al. Surgical resection of hepatic metastasis from gastric cancer: a review and new recommendation in the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17(2):206–12.

Nomura T, Kamio Y, Takasu N, Moriya T, Takeshita A, Mizutani M, et al. Intrahepatic micrometastases around liver metastases from gastric cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16(4):493–501.

Komeda K, Hayashi M, Kubo S, Nagano H, Nakai T, Kaibori M, et al. High Survival in Patients Operated for Small Isolated Liver Metastases from Gastric Cancer: A Multi-institutional Study. World J Surg. 2014 .

Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, Iveson T, Nicolson M, Coxon F, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(1):36–46.

Koizumi W, Kim YH, Fujii M, Kim HK, Imamura H, Lee KH, et al. Addition of docetaxel to S-1 without platinum prolongs survival of patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomized study (START). J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(2):319–28.

Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim DH, Park KW, Oh SY, Kwon HC, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1513–8.

Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9742):687–97.

Yokoyama H, Ikehara Y, Kodera Y, Ikehara S, Yatabe Y, Mochizuki Y, et al. Molecular basis for sensitivity and acquired resistance to gefitinib in HER2-overexpressing human gastric cancer cell lines derived from liver metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(11):1504–13.

Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Guo W, Xiong J, Bai Y, et al. Apatinib for chemotherapy-refractory advanced metastatic gastric cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3219–25.

Wang YN, Shen KT, Ling JQ, Gao XD, Hou YY, Wang XF, et al. Prognostic analysis of combined curative resection of the stomach and liver lesions in 30 gastric cancer patients with synchronous liver metastases. BMC Surg. 2012;12:20.

Ambiru S, Miyazaki M, Ito H, Nakagawa K, Shimizu H, Yoshidome H, et al. Benefits and limits of hepatic resection for gastric metastases. Am J Surg. 2001;181(3):279–83.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no: 81273187).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

W. Zhang and Y. Yu contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, W., Yu, Y., Fang, Y. et al. Systemic chemotherapy as a main strategy for liver metastases from gastric cancer. Clin Transl Oncol 17, 888–894 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-015-1321-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-015-1321-z