Abstract

Economic expansion and recession have shaped the long-term evolution of local economic systems, exemplifying causes and consequences of territorial disparities and alimenting the debate on regional resilience. The present study investigates changes (2004–2013) in the spatial structure of two labour market indicators in Italy (participation and unemployment rates) during the most recent expansion and recession waves, so as to identify socioeconomic and territorial factors influencing short-term performances of local labour markets. Specialization in advanced industry (such as precision mechanics) is one of the most important factors associated to low employment losses during recession in Italy. Our results offers a contribution to the debate on regional resilience by reconnecting it to the more general issue of spatial disparities. We aim to shed light on the impact of institutional change and external shocks on the evolutionary path of local economic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Long run structural changes in regional economies have attracted a vast literature hinged on both neoclassical equilibrium theory and the evolutionary approaches recently introduced by the New Economic Geography (Patacchini and Rice 2007; Kemeny and Storper 2015; Martin and Sunley 2015a). Spatial distribution of income and wealth, structure of local labour markets, differentials in employment and unemployment rates among areas, together with changes in the urban hierarchy, have been crucial issues in regional science for a long time and still represent a challenge in a world dominated by economic stagnation and uncertain factors of growth (Soares et al. 2003; Rice et al. 2006; McCann and Ortega-Argilés 2013; Armstrong et al. 2014; Gerolimetto and Magrini 2016). In a perspective of renewed and widened regional disparities (Taulbut and Robinson 2015), identifying (and defining the spatial relationship between) drivers of socioeconomic divides is a key research issue with both theoretical and policy implications (del Campo et al. 2008; Mulligan 2010; Storper 2011; Magrini et al. 2015).

Long-run regional economic development has usually been interpreted as a homogeneous trajectory shaped by different types of shocks impacting “on regional linkages and networks, in turn leading to possible changes in trajectories or triggering path-shifting processes that require an ability to mobilize and recombine agents and resources into new development frameworks” (Bailey and de Propris 2014). In the last decade, the rapid succession of expansion and recession waves influenced considerably the medium-term evolution of regional economic systems, strengthening the debate on regional resilience and connecting it to the more traditional issue of spatial disparities in socioeconomic variables (Simmie and Martin 2010; Fingleton et al. 2012; Martin 2012). In Europe, recession impacted mostly economically weak Mediterranean regions, compared to northern regions. Thus, the analysis of regional economic dynamics during recession in southern Europe allows an empirical verification of concepts such as ‘resilience’, ‘resistance’, ‘recovery’, ‘re-orientation’ and ‘renewal’ applied to the recent evolution of local systems undergoing relevant socioeconomic, political and cultural changes (e.g. Pike et al. 2010; Benediktsson and Karlsdóttir 2011; Glaeser et al. 2014; Kemeny and Storper 2015).

So far, the concept of ‘resilient region’ has been applied mainly to affluent regions, either through empirical testing of economic theory or under exploratory approaches evaluating target variables or sets of indicators (Hassink 2010; Hudson 2010; Hincks et al. 2004). By recognizing the ongoing global crisis as a major turning point in regional systems, resilience-based approaches have been inspired, in some cases, by definitions and operational frameworks typical of evolutionary economic geography (Bristow and Healy 2014). Important results in this field were achieved investigating the effects of the recent financial crisis on regional growth, employment and investment (Bailey and de Propris 2014).

Assessing the intimate relationship between socio-spatial structure and economic performance of local labour markets is a relevant issue in regional economics and contributes to the study of socioeconomic disparities at both national and supra-national levels. Economic performance of local districts has been related to spatial differentials in employment and unemployment rates (Patacchini and Zenou 2007; Naito 2012; Bande and Karanassou 2013; Fratesi and Percoco 2013; Green and Livanos 2015; Taulbut and Robinson 2015). The short-term development of local economic systems has been interpreted as the result of short-term recession dynamics and as a proxy of regional resilience (Hassink 2010; Hudson 2010; Pike et al. 2010; Hincks et al. 2004; Martin and Sunley 2015b). Temporal variations in unemployment can be interpreted as an implicit indicator of resistance to economic shocks or post-shock recovery (Salvati et al. 2016).

In a recent work on the impact of the 2008–2009 recession on unemployment in the largest 60 cities of UK, Lee (2014) identified the main determinants of the resilience of urban economies to unexpected shocks. Cities with the highest proportion of people employed in financial services, manufacturing and construction have experienced the lowest increases in the unemployment rate. The well-known spatial determinants of socioeconomic disparities in the UK have also played a role in the scattered growth of the unemployment rate during recession, with wealthier regions in Britain and Scotland performing better than other regions. An important feature of urban resilience is human capital and especially the stock of skilled workers: Lee found unemployment rates to be less growing in cities with high-skilled population, that can attract businesses, stimulate innovation and create value more quickly. At the same time, the ‘resilience gap’ caused by short term economic shocks could exacerbate regional disparities in unemployment (e.g. Rice et al. 2006; Patacchini and Rice 2007; Taulbut and Robinson 2015), determining spatial effects in socio-demographic processes that deserve further investigation (e.g. Proietti 2005; Fischer et al. 2009; Edzes et al. 2015).

Like the UK, Italy is a developed economy in Europe with considerable socioeconomic disparities (Dunford and Greco 2007; Dunford 2008; Dow et al. 2012; D’Agostino and Scarlato 2013). Local unemployment rates diverge by more than 20 points between the richest areas of northern Italy and the poorest southern regions. In the most recent decade, the slow economic growth and the subsequent stagnation stimulated moderate changes in the industrial structure at both the national and regional scales. Conversely, local labour markets have evolved rapidly, in part due to political reforms that, since 1997, have opened highly-regulated local markets to competition, flexibility and temporary jobs. Flexibility was invoked as a response to youth unemployment and inherent disparities in the job market between northern and southern regions, contributing to the uneven internal migration of skilled workers towards northern Italy (Faini et al. 1997; Fratesi and Percoco 2013; Iammarino and Marinelli 2015).

The reform of the labour market came into force in 1997 (the so called ‘Treu’ law) and was revised and improved by a subsequent law (the so called ‘Biagi’ law) in 2003. These reforms positively impacted the Italian labour market—considered one of the most rigid in Europe—by increasing the flexibility of contracts, reducing recruitment constraints and introducing new institutions responsible for the matching between labour supply and demand. On the whole, job reforms, combined with slightly positive economic dynamics, pushed the unemployment rate to the historic low in 2007 (6.1%), with relevant decreases in female and youth unemployment rates (Battaglia and Iraldo 2011). However, in an economic structure dominated by small-size firms such as Italy, reforms also contributed to a progressive de-regulation of local markets promoting more temporary jobs than expected. Unemployment rates rose again in the subsequent years as a result of recession, reaching 8.9% in 2010 and 12.2% in 2013, the peak value observed in the time series since 1977.

Due to the short-term relationship between the evolution of local labour markets (increased regional disparities in the rate of activity and employment, consolidating the north–south divide in youth unemployment) and structural reforms at the national scale, the recent Italian development path provides a unique opportunity to test hypotheses on the socioeconomic resilience of local districts. Empirical analysis may benefit from the new time-series of labour market indicators at a fine spatial scale disseminated annually, since 2004, by the National Institute of Statistics. This data set includes participation and unemployment rates at the level of local labour markets in Italy (686 districts as defined in 2001) and allows accurate spatial analysis of pre- and post-recession economic dynamics, e.g. in terms of reduction (or expansion) of regional disparities in unemployment rate. The effects of institutional changes (in this case, labour reforms) on local labour markets performances can be also investigated (Storper 2011; Rodríguez-Pose 2013; McCann and Ortega-Argilés 2013; Boschma 2015; Martin and Sunley 2015a).

Based on these premises, the present study assesses changes in the spatial structure of the two aforementioned indicators during employment growth in Italy (2004–2007), in the subsequent job shortage following recession (2007–2010) and in the most recent crisis period (2010–2013) dominated by a stable participation rate and a progressive increase in unemployment rates. By compiling a database of more than 70 socioeconomic and territorial indicators, the analysis identifies which factors have a stronger impact on the dynamics of participation and unemployment rates on a district scale. While the rationale here proposed is eminently exploratory (Serra et al. 2015), it attempts to overcome the supposed limits of the descriptive approach typical of the ‘regional resilience’ paradigm (Christopherson et al. 2010). In this approach, the socioeconomic environment is seen as a powerful factor influencing the resilience potential of local districts (Salvati 2016). Our results contribute to the debate on socioeconomic resilience connecting it to the more general issue of regional disparities, and shed light on the impact of institutional changes and external shocks on the evolutionary path of local economic systems (Boschma 2015).

The paper is organized as follows. The next section covers data collection and describes the methodological framework. The subsequent section illustrates evidence related to changes in the spatial distribution of participation and unemployment rates across the Italian local labour markets, testing for intrinsic differences based on place-specific factors. The final section interprets these empirical results in light of regional resilience and offers some concluding remarks.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study area

Italy is a southern European country extending 302,070 km\(^{2}\) with 23% lowlands, 42% uplands and 35% mountainous areas. The partition into two geographical divisions (Northern-Central Italy and Southern Italy including the two main islands, Sicily and Sardinia), widely used in official statistics, reflects the long-established disparities still observed in the country. Extending well beyond the industry-service dichotomy, regional divides in Italy reveal a wide-range impact on urban structures and involve socioeconomic processes acting at vastly different spatial scales, from national to local (Bonavero et al. 1999). Northern Italy encompasses the Italian tract of the “blue banana” European region and includes some of the wealthiest regions in the continent, such as Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia-Romagna. Separated from northern Italy by the Apennines mountain, Central Italy is a polarized region with a marked urban–rural divide and a mixed economic structure centred on small-scale manufacturing, tourism and high-quality agriculture. Southern Italy is a disadvantaged region with a younger population structure, more restricted accessibility from Europe and a production structure centred on low-income agriculture and traditional services (constructions, commerce and the public sector) concentrating in compact urban areas.

2.2 Labour market indicators

Two labour market indicators (participation and unemployment rates) were made available on a year basis for the time interval 2004–2013 at the district scale in Italy. Participation rate (labelled as ‘p’) was calculated as the ratio of total workforce (employed and unemployed) to the resident population in age >14 and <74 years per each year of the time interval. Unemployment rate (labelled as ‘u’) was calculated as the ratio of population actively seeking for a job to the total workforce, as described above. The percent rate of change over three consecutive intervals of equal length (2004–2007, 2007–2010, 2010–2013) was also calculated for both indicators. Empirical analysis was carried out using the 686 travel-to-work areas (the so called ‘Sistemi Locali del Lavoro’ or Local Labour Market Areas, LLMAs) as the elementary spatial unit. LLMAs have been identified by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat 2006) based on commuting data collected in the 2001 National Census of Population (Istat 1997). LLMAs reflect districts of socioeconomic interest and were widely used to analyze e.g. the regional development of Italy (Pellegrini 2002), the local specialization in agriculture (Giusti and Grassini 2007), and the impact of land quality on economic growth (Salvati et al. 2011).

2.3 Background variables

Based on the analysis of multiple drivers of change, our approach aims at illustrating the complexity of local labour market dynamics in expansion and recession waves. The economic, social and demographic indicators tested for possible impact on local labour market performances in Italy were organized in the following domains: (i) territorial aspects including topography (7 indicators), (ii) land-use distribution (5), (iii) settlement characteristics (7), (iv) district specialization (6), (v) economic performances (11), (vi) productive structure (27), (vii) education level (3) and (viii) demographic attributes, including population structure and dynamics (8).

Contextual indicators were derived from statistical data sources (mainly Italian National Institute of Statistics and Corine Land Cover maps of Italy) at the local district scale and refer to the beginning of the study period (2004–2007), with some variables recorded in 2001 because of restrictions in the availability of more recent statistical data . A total of 74 indicators were calculated for each Italian LLMA (Table 1). Research domains and indicators have been chosen according to previous works in the field of regional analysis (Soares et al. 2003; del Campo et al. 2008; Dallara and Rizzi 2012; Salvati et al. 2014) and labour economics in Italy (Faini et al. 1997; Cracolici et al. 2007). Although the indicators chosen in the present study can be considered as a partial outlook to the vastly different Italian socioeconomic contexts, they provide a broad qualification of the economic structure and socio-demographic traits observed in each local labour market.

2.4 Data analysis

The analysis framework developed in this study was based on multivariate statistics and spatial techniques. Such an approach was preferred to formalized econometric techniques since the aim of this study was eminently exploratory. Exploratory approaches based on a large set of relevant indicators are broadly conceived and rather frequent in resilience science (e.g. del Campo et al. 2008). They allow to consider the impact of variables supposed to be indirectly correlated with labour market dynamics in a comprehensive way and to underline latent resilience dimensions that might be demised from a traditional econometric analysis.

2.4.1 Descriptive and correlation statistics

Descriptive statistics and maps of the two labour market indicators (participation and unemployment rates) by time interval were calculated with the aim to assess changes in the labour market performances between northern and southern Italy during 2004–2013. Spearman non-parametric rank tests were run to assess significant pair-wise correlations between each labour market indicator and each contextual indicator. Significance was set up at \(p<\) 0.05 after Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons.

2.4.2 Multivariate analysis

A principal component analysis (PCA) was undertaken on the data matrix composed of the labour market indicators by LLMA with the aim to evaluate latent relations between unemployment and participation rates over time and space. We run a second PCA on the matrix composed of a selection of the 74 contextual indicators described above, where some were removed simply to avoid multi-collinearity (see Table 1); labour market indicators were considered as supplementary variables. This analysis was aimed at identifying the latent factors shaping changes in the labour market indicators at the beginning of the study interval and during the three phases described above (expansion, early decline, recession), identifying place-specific variables and relevant research domains. As the PCA was based on the correlation matrix, the number of relevant axes (m) was chosen by retaining the components with eigenvalue >3. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, which tests whether the partial correlations among variables are small, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which tests whether the correlation matrix is an identity matrix, were used to assess the quality of the PCA outputs. These tests evaluate the appropriateness of the factor model when analyzing the original data.

2.4.3 Regression analysis

The geographically weighted regression (GWR) framework proposed by Fotheringham et al. (2002) was finally used to identify (and rank the impact of) the most relevant indicators in the spatial distribution of participation and unemployment rates. Model specification was based on the results of the PCA to avoid misspecification due to indicators’ collinearity. The scores of the components with eigenvalue >3 (see above) were regarded as predictors with the objective to include relevant, independent dimensions affecting local labour markets. Predictors were tested for correlation separately with each labour market indicator (the 2004 ‘benchmark’ values: p04 and u04, and the rates of change over the subsequent time intervals: p07 and u07, p10 and u10, p13 and u13) taken as dependent variables.

The methodological framework underlying GWR uses a kernel function to calculate weights for the estimation of local weighted regression models. Contrary to the standard regression model, where the regression coefficients are location-invariant, the specification of a basic GWR model for each location s = 1, ..., n, is:

where y(s) is the dependent variable at location s, X(s) is the row vector of explanatory variables at location s, b(s) is the column vector of regression coefficients at location s, and e(s) is the random error at location s. Hence, regression parameters, estimated at each location by weighted least squares, vary in space, implying that each coefficient in the model is a function of s, a point within the geographical space of the study area. As a result, GWR gives rise to a distribution of local estimated parameters, modelling socioeconomic processes that are non-stationary in space (Ali et al. 2007; Manca et al. 2014). The weighting scheme is expressed as a kernel function that places more weight on the observations closer to the location s. In this study, we adopted one of the most commonly used specifications of the kernel function, which is the bi-square nearest neighbour function. All variables were standardized prior to analysis.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics of job market indicators

Trends in participation and unemployment rates in Italy (1977–2013) are illustrated in Fig. 1. Unemployment rate increased from an average rate of 6.5–7% at the end of the 1970s to a stable rate of 9–10% in the 1980s, decreasing up to 8% at the end of the decade. Unemployment rate increased again up to 11% in the 1990s showing a slight but continuous decline between late 1990s and 2007 and a rapid increase afterwards. The minimum value observed in the time-series (6.1%) was recorded in 2007, representing a structural break distinguishing a period of unemployment decline (due to the joint effect of moderate economic growth and job reforms) and the 2008–2009 recession. Unemployment rate reached the highest observed value in 2013 (12.2%) doubling the value recorded in 2007. Following a period of slight increase between the end of the 1970s and mid-1990s, participation rate increased rapidly since the end of the 1990s approaching 64% in 2012 and 2013.

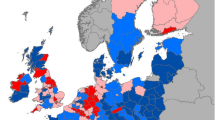

The spatial distribution of the two indicators in the Italian local labour markets was illustrated in Fig. 2 as crude rate for 2004 and as percent rate of change for three subsequent time intervals (2004–2007, 2007–2010 and 2010–2013). The traditional north–south divide in the performance of local labour markets was evident at the beginning of the study period. Participation rate was over 50% in the majority of northern Italy districts and in a number of central Italy districts with the exception of poorly-accessible rural and mountain areas. In southern Italy, the only districts with participation rate above 50% were found in Sardinia (the metropolitan areas of Cagliari and Sassari and the touristic district of Gallura). Unemployment rate was found below 5% in flat and accessible districts of the Po plain, and below 10% in central Italy districts and in mountain, less-accessible northern Italy districts. Southern districts displayed a rate frequently exceeding 10% or even 15% in some cases (the metropolitan area of Naples, southern Sardinia including Cagliari, most Sicily districts including Palermo, the regional capital, some internal, rural districts of Calabria, Basilicata and Apulia). Unemployment rate increased with participation rate (Spearman correlation coefficient, r\(_{\mathrm{s}}\) = 0.90, n = 686, \(p<\) 0.001).

During 2004–2007, unemployment rate decreased more rapidly in southern districts than in northern districts. This process was accompanied with a decline in participation rate in southern Italy and a slight increase in northern Italy. The resulting change in the participation rate showed a fragmented and spatially-heterogeneous distribution with higher gains observed in rural areas of northern and central Italy than in urban, coastal and internal flat districts.

Trends in the job market indicators observed in the subsequent time interval (2007–2010) reflect the negative impact of the 2008–2009 recession, determining a spatially-diffused increase of the unemployment rate in the whole of Italy. The largest increases were concentrated in high-density, industrial areas of northern and central Italy and medium-density rural areas of southern Italy. The decline in participation rate observed in southern Italy (except some touristic and coastal districts in Sardinia, Sicily and Basilicata) contrasts with the moderate increase recorded in central and northern districts. Changes in participation rate at the local scale were not correlated with changes in unemployment rate. Widespread and sharp increases in the unemployment rate occurred in the most recent time interval (2010–2013). Participation rate increased in both northern and southern Italy being positively correlated with unemployment rate (r\(_{\mathrm{s}}\) = 0.25, n = 686, \(p<0.05\)).

A PCA was finally developed to summarize the spatial correlation in the job market indicators during the 4 time intervals analyzed (2004, 2004–2007, 2007–2010, 2010–2013). The PCA extracted two components explaining 61.4% of the total variance (Fig. 3). Component 1 (38.7% of the total variance) outlines the north–south divide in the Italian job market. Participation rate in 2004 (higher in northern Italy than elsewhere in Italy) showed positive loadings; unemployment rate (higher in southern Italy than elsewhere in Italy) clustered along the negative side of this axis. While percent changes in the unemployment rate between 2004 and 2007 were positively associated with component 1, changes in the unemployment rate in the subsequent time interval (2010–2013) followed the reverse pattern. Component 2 (22.7% of the total variance) outlines a different spatial pattern for the percent changes in participation rate over 2007–2010 (higher gains observed in northern Italy) and 2010–2013 (widespread increases across the country).

Principal component analysis applied to selected local labour market indicators in Italy (see the Sect. 2 for acronyms and technical details)

3.2 Local labour markets and contextual indicators

3.2.1 Correlation analysis

Spearman non-parametric correlations identified significant relationships between job market indicators and contextual indicators at the LLMA scale (Table 2). Participation rate at the beginning of the study period (2004) showed a marked north–south divide (SOU), being significantly higher in industrial districts (IN%) specialized in mechanics (DK) and with an above-average per-capita disposable income (VAP), propensity to export (WEP and EXP), labour productivity in industry (PIN) and services (PSE) and size of local units (SIZ). In these districts above-average values were also observed for the following indicators: population growth rate (GRO), density of foreign citizens (MIG), incidence of upper secondary education (DEG), percentage of civil weddings (WED) and incidence of rented houses (REN). Participation rates decreased significantly in de-specialized districts (DES) displaying above-average share of agriculture in total district value added (AG%), density of workers in constructions (F), commerce (G), health and other public services (N), and incidence of non-occupied dwellings (EMP). Unemployment rate (2004) showed the reverse correlation profile.

Changes in participation and unemployment rates between 2004 and 2007 showed a marked north–south divide. Both indicators decreased in local districts with an economic structure dominated by commerce, increasing in districts with high per-capita disposable income, above-average labour productivity in industry and propensity to export, larger firms and job attractiveness. These results pinpoint at the process of north–south convergence in unemployment rates in Italy, when unemployment decreases were observed mainly in economically-disadvantaged districts, although with a decreasing participation to the job market. Economically-leading districts attracted workers and the increasing participation rate was reflected in a higher unemployment rate. Participation rate between 2007 and 2010 declined in southern Italy and increased slightly in northern Italy. The declining participation to the job market in southern Italy did not impact unemployment rates.

While changes in participation rate during economic stagnation (2010–2013) were found to be uncorrelated with any contextual indicator, unemployment rate increased in southern Italy, mainly in de-specialized districts with an economic structure dominated by commerce. Conversely, unemployment rates increased less rapidly or even decreased in the wealthier districts of Italy, characterized by above-average per-capita disposable income, share of industry in the total product, labour productivity in industry, propensity to export, firm size and percentages of foreign people and civil weddings.

3.2.2 Principal component analysis

Results of the PCA run on the 74 contextual indicators provided a comprehensive outlook of the multiple relationships between labour market indicators and the local socioeconomic context. The PCA extracted four components (48% of the total variance): labour market indicators were considered as supplementary variables in the PCA and analyzed for correlation with each component extracted (Table 3). Component 1 extracted 21% of the total variance with more than 10 indicators displaying high (positive or negative) loadings. Component 1 represents a gradient of economic performances (per-capita income, labour productivity in both industry and services, firm size) and industrial specialization (precision mechanics with high propensity to export) discriminating northern districts from southern districts. Performing and wealthier districts—mainly located in northern and central Italy—attracted workers from less-performing or disadvantaged districts and from abroad. Participation and unemployment rates in 2004 and changes in participation and unemployment rates between 2004 and 2007 were correlated with component 1.

Component 2 (12% of the total variance) identifies the urban–rural gradient in Italy. Compact urban districts with an economic structure based on specialized services (research and development, real estate, finance and banking) and high density of skilled workers contrasted with suburban and rural districts with the highest share of industrial product in the total product. Unemployment rate in 2004 and changes in unemployment rate (2004–2007) were associated with component 2. Unemployment rate in 2004 was higher in service-oriented local labour markets. Unemployment rate during 2004–2007 increased in industrial districts and decreased in service-oriented local labour markets.

Component 3 (9% of the total variance) identifies a land-use gradient associated with specific attributes of the demographic structure and human settlements at the local scale (average number of components per family, non-occupied houses, dwelling size, accessibility). Participation rate increased during 2004–2007 in less accessible districts. Component 4 (6% of the total variance) illustrates a gradient of ‘tourism attractiveness’ separating tourism-specialized districts (young population, above-average percentage of mono-nuclear families and rapid urban expansion) from economically-disadvantaged, de-specialized districts characterized by population aging. Participation rate in 2004 was found moderately associated with component 4.

3.2.3 Geographically weighted regression

The relationship between local labour market indicators and the principal components described above was investigated through a GWR producing models with different goodness-of-fit (Table 4). As a general rule, the models running on the dependent variables measured at the beginning of the study period (p04, u04) performed better than the models running on the rates of change over time. Unemployment rate performed better than participation rate as dependent variable irrespective of the time interval analyzed.

Spatial disparities in 2004 participation rate were satisfactorily explained (global adj-R\(^{2}\) = 0.91) by a GWR model using component scores as predictors (Fig. 4). Local R\(^{2}\) coefficients were particularly high in northern Italy and in some areas of central and southern Italy (Marche, Sardinia, part of Apulia and Basilicata). Component 1 (‘economic performances and industrial specialization’) influenced positively the participation rate in some rural areas of northern and central Italy and in southern Sicily and a similar pattern was observed for component 2 (‘rural–urban divide’). Component 3 (‘district accessibility and land-use’) had the major impact on northern Italy districts and restricted areas of central Italy located between Tuscany and Marche. Component 4 (‘tourism and natural amenities’) outlined the negative correlation between population aging and participation rate in northern and central Italy, with participation rate in southern Italy being positively affected by tourism specialization.

Geographically weighted regressions with participation rate (as the dependent variable) and the four extracted principal components (Table 3) as predictors by time period

Scores of the 4 principal components explained spatial changes in participation rate between 2004 and 2007 with a global adjusted R\(^{2}\) by 0.40. Local R\(^{2}\) coefficients were higher in some districts of central and southern Italy. Both the economic performance gradient (component 1) and the urban–rural divide (component 2) influenced positively the rate of participation to the job market of both central and southern Italy. A negative association was found with land-use gradient (component 3) in north-eastern Italy, Apulia and southern Sardinia. Component 4 showed negative coefficients in north-western regions and in districts situated at the boundary between central and southern Italy.

GWR produced less powerful models for the two dependent variables in the time intervals 2007–2010 and 2010–2013 with adjusted R\(^{2}\) generally lower than 0.4 and high local R\(^{2}\) scattered across Italy. The performance gradient and the urban–rural divide influenced the change in participation rates (2007–2010) more in southern districts than elsewhere in Italy. The land-use gradient was negatively associated with changes in participation rate over 2007–2010 in northern Italian districts; the reverse pattern was observed in the following time interval. Our results indicate that, with economic growth, the positive impact of agglomeration economies (e.g. industrial specialization, economic performances and urban concentration) on the participation rate was more evident in central and southern Italy. Accessibility, land-use and tourism specialization became the most relevant factors during recession with distinct impacts on participation rates in northern and southern districts.

The spatial distribution of the 2004 unemployment rate in Italy was satisfactorily explained (global adjusted R\(^{2}\) = 0.88) by a GWR model with the 4 principal components as predictors (Fig. 5). Local R\(^{2}\) were found to be particularly high in districts situated in Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Abruzzo and Apulia. Unemployment rate was lower in urban and peri-urban districts with high economic performances. The negative impact of component 4 on the unemployment rate was relatively widespread in central and southern Italy.

Geographically weighted regressions with unemployment rate (as the dependent variable) and the four extracted principal components (Table 3) as predictors by time period

Changes in the local unemployment rate during economic expansion were satisfactorily explained by the 4 component scores (global adjusted R\(^{2}\) = 0.58). Local R\(^{2}\) coefficients were found to be higher in northern Italy and in some areas of central and southern Italy than elsewhere in Italy. Factors associated to district economic performances and the urban–rural gradient had a positive influence on the unemployment rate in central-southern Italy. While component 3 had the highest (negative) impact on Sicily and southern Sardinia districts, component 4 showed negative coefficients in north-eastern Italy and in districts placed at the boundary between central and southern Italy.

The GWR produced a relatively poor model for the subsequent phase (2007–2010), with adjusted R\(^{2}\) lower than 0.27 and relatively high local R\(^{2}\) observed only in a restricted part of north-eastern Italy. Spatial trends were comparable with what was observed between 2004 and 2007. The GWR model for 2010–2013 performed better (adjusted R\(^{2 }=^{ }\) 0.55). North-east and central-southern districts showed local R\(^{2}\) coefficients higher than those observed for the rest of Italy. The spatial impact of the four principal components changed slightly compared to the precedent time intervals with higher and positive impact of all components in northern and central districts compared with southern districts. In conclusion, GWR models showed a substantial stability in the spatial coefficient of the 4 component scores with a moderate north–south divide. These results suggest that recession did not alter the spatial relation between unemployment rate and the indicators associated to the selected components.

4 Discussion

Given the inherent spatial complexity of the Italian Local Labour Markets (Patacchini 2008), exploratory frameworks based on multivariate statistics and spatial techniques provide a comprehensive analysis of the main determinants and contextual factors shaping job market characteristics and performances over time (Rice et al. 2006). The present study has analyzed spatio-temporal trends of selected labour market indicators in Italy with the aim to identify the socioeconomic profile of local districts experiencing changes in participation and unemployment rates over expansion and recession waves. Our study moves in a regional resilience perspective when exploring the spatio-temporal pattern of the unemployment rate, considered a sensitive variable to economic shocks and a proxy for resilience capability (Lee 2014). Since the spatial dynamics of the unemployment rate during economic expansions and recessions has been interpreted as a possible measure of local labour market resilience (Davies 2011), we finally identified the socioeconomic characteristics of the districts that have experienced the best performances in the two economic phases.

Under economic expansion, employment grew especially in economically-weak districts, fuelling a process of slow convergence in labour market indicators between northern and southern Italy. Employment gains, however, have partly benefited from a progressive reduction in the participation rate in southern Italy (Dunford 2008). In northern Italy, a low unemployment rate was associated with increasing participation rates at the local scale, possibly reflecting the higher job attractiveness compared to the rest of Italy (Patacchini 2008).

According to previous studies on socioeconomic resilience in European regions (see for instance Davies 2011), the analysis of local labour markets’ dynamics at the onset of the economic crisis led to mixed results. The correlation profile of the unemployment rate in 2010–2013 is specular to what was observed in 2004–2007, suggesting that the employment gains achieved by lagging districts during economic expansion were subsequently lost with recession. Economically-leading industrial districts in northern Italy were experiencing the lowest recession impact on labour market performances. In other words, recession influenced negatively the north–south convergence process stimulated by the 1997 and 2003 job market reforms, showing a more intense impact on the weakest local labour markets in southern Italy. District specialization in advanced industry (such as precision mechanics) was found to be one of the most relevant factors associated to low employment losses during recession. Interestingly, the socioeconomic profile of districts with the highest gain (and loss) in unemployment rates during expansion (and recession) was quite specular. These results candidate 2007 as the turning point from the process of north–south convergence observed during 2004–2007 to a more heterogeneous regime with wealthy districts better resisting to recession.

Urban areas and districts with an economic structure centred on advanced services occupied an intermediate position between industrial areas of northern Italy, and economically-disadvantaged, rural areas of central and southern Italy with low-skilled workers and a productive structure based on construction, commerce and the public sector (Dunford and Greco 2007). These results appear to be in partial disagreement with what was presented by Lee (2014) for the dynamics of the unemployment rate in the UK during the 2008–2009 recession. Lee points out that the largest urban areas with an economic structure centred on advanced services and skilled workforce (high percentage of university graduates) tend to be less exposed to economic shocks, showing slower unemployment increases than areas with a more traditional, mixed industrial-service economic structure and less skilled workers. The major differences between Italy and the UK can be attributed to the economic structure (Patacchini and Rice 2007) centred on small firms with high propensity to export (such as those specialized in precision mechanics) in Italy. Moreover, regional disparities in participation and unemployment rates are particularly complex in Italy.

Recession has undoubtedly created favourable conditions for a process of divergence between wealthy regions—better protected from economic shocks—and economically-weak local districts (Proietti 2005; Pike et al. 2010; Cellini and Torrisi 2014). Moreover, the analysis of Italian LLMAs suggests that “disparities tend to enlarge during slowdowns, that is, during periods in which it is reasonable to expect that fewer resources could be devoted to short-term policies aimed at tackling them” (Magrini et al. 2015, p. 264). This result is in partial disagreement with the indication coming from empirical studies, that show how regions characterized by a greater firm diversification may be more resilient to economic shocks (Frenken et al. 2007). In our case, the diversification of the local economic structure was the highest in medium-income districts of northern Italy, suggesting that related variety may reinforce the resistance of industrial districts to economic shocks (Fingleton et al. 2012).

The importance of human capital with high qualification as a resilience factor has also been emphasized in previous studies (Bristow and Healy 2014). In this perspective, Italy differs somewhat from the stylized facts showing that the percentage of graduates (from secondary school) is higher in industrial districts more resistant to shocks (Faini et al. 1997), contrary to what was observed for the percentage of (university) graduates. These findings—possibly related to the education-job mismatch that characterizes Italy and especially southern Italy (see Iammarino and Marinelli 2015 and references therein)—underscore the importance of path-dependent processes shaping resilience of the Italian regions (see Sensier and Artis 2014 and references therein).

5 Conclusion

Results of our study suggest how policies that introduced more flexibility in the labour market have contributed to a regime shift that improved the resistance of weaker local systems to short-term economic shocks. At the same time, the outcome of these policies have occasionally reflected controversial situations, such as the decrease in the unemployment rate and the simultaneous decrease in the rate of participation in the labour market observed in the period 2004–2007. These evidence answer to the call “to investigate more systematically which institutional structures in regions are responsive to new growth paths (...) to what extent is institutional change required for the development of new growth paths in regions” (Boschma 2015, p. 738) and definitely show the relevance of studies considering recession, changes in institutional arrangements and local resilience as possible driving forces of regional economic growth.

References

Ali, K., Partridge, M.D., Olfert, M.R.: Can geographically weighted regression improve regional analysis and policy making? Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 30(3), 300–329 (2007)

Armstrong, H., Ballas, D., Staines, A.: A comparative classification of labour market characteristics of British and Greek small islands. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 21(2), 222–248 (2014)

Bailey, D., de Propris, L.: Editorial: recession, recovery and resilience? Reg. Stud. 48(11), 1757–1760 (2014)

Bande, R., Karanassou, M.: The natural rate of unemployment hypothesis and the evolution of regional disparities in Spanish unemployment. Urban Stud. 50(10), 2044–2062 (2013)

Battaglia, M., Iraldo, F.: Spatial effects of labour policies promoted in Italy from 1996 to 2006: an analysis in the EU context. Eur. Plan. Stud. 19(2), 311–330 (2011)

Benediktsson, K., Karlsdóttir, A.: Iceland: crisis and regional development—thanks for all the fish? Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 18(2), 228–235 (2011)

Bonavero, P., Dematteis, G., Sforzi, F.: The Italian Urban System. Towards European Integration. Ashgate, Aldershot (1999)

Boschma, R.: Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Reg. Stud. 49(5), 733–751 (2015)

Bristow, G., Healy, A.: Regional resilience: an agency perspective. Reg. Stud. 48, 923–935 (2014)

Cellini, R., Torrisi, G.: Regional resilience in Italy: a very long-run analysis. Reg. Stud. 48(11), 1779–1796 (2014)

Christopherson, S.J., Michie, J., Tyler, P.: Regional resilience: theoretical and empirical perspectives. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 3, 3–10 (2010)

Cracolici, M.F., Cuffaro, M., Nijkamp, P.: Geographical distribution of unemployment: an analysis of provincial differences in Italy. Growth Change 38(4), 649–670 (2007)

D’Agostino, G., Scarlato, M.: Innovation, socio-institutional conditions and economic growth in Italian regions. Reg. Stud. (2013). doi:10.1080/00343404.2013.838000

Dallara, A., Rizzi, P.: Geographic map of sustainability in Italian local systems. Reg. Stud. 46(3), 321–337 (2012)

Davies, S.: Regional resilience in the 2008–2010 downturn: comparative evidence from European countries. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 4, 369–382 (2011)

del Campo, C., Monteiro, C.M.F., Oliveira Soares, J.O.: The European regional policy and the socio-economic diversity of European regions: a multivariate analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 187, 600–612 (2008)

Dow, S., Mantagnoli, A., Napolitano, O.: Interest rates and convergence across Italian regions. Reg. Stud. 46, 893–905 (2012)

Dunford, M.: After the three Italies the (internally differentiated) north–south divide: analysing regional and industrial trajectories. Annales de Géographie 6(664), 85–114 (2008)

Dunford, M., Greco, L.: Geographies of growth, decline and restructuring: the rise and fall (privatization) of the state-owned steel sector and the trajectories of steel localities in the Italian Mezzogiorno. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 14(1), 27–53 (2007)

Edzes, A., Hamersma, M., Venhorst, V., van Dijk, J.: Labour market performance and school careers of low educated graduates. Lett. Sp. Resour. Sci. 8(3), 267–289 (2015)

Faini, R., Galli, G., Gennari, P., Rossi, F.: An empirical puzzle: falling migration and growing unemployment differential among Italian regions. Eur. Econ. Rev. 41(3–5), 571–579 (1997)

Fingleton, B., Garretson, H., Martin, R.: Recessionary shocks and regional employment: evidence on the resilience of UK regions. J. Reg. Sci. 51, 109–133 (2012)

Fischer, M.M., Bartkowska, M., Riedl, A., Sardadvar, S., Kunnert, A.: The impact of human capital on regional labor productivity in Europe. Lett. Sp. Resour. Sci. 2(2–3), 97–108 (2009)

Fotheringham, A.S., Brunsdon, C., Charlton, M.: Geographically Weighted Regression. The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships. Wiley, Chichester (2002)

Fratesi, U., Percoco, M.: Selective migration, regional growth and convergence: evidence from Italy. Reg. Stud. 48, 1650–1668 (2013)

Frenken, K., Van Oort, F., Verburg, T.: Related variety, unrelated variety, and regional economic growth. Reg. Stud. 41, 685–697 (2007)

Gerolimetto, M., Magrini, S.: A spatial analysis of employment multipliers in the US. Lett. Sp. Resour. Sci. 9(3), 277–285 (2016)

Giusti, A., Grassini, L.: Local labour systems and agricultural activities: the case of Tuscany. Int. Adv. Econ. Res. 13, 475–487 (2007)

Glaeser, E.L., Giacomo, A.M., Tobio, K.: Cities, skills and regional change. Reg. Stud. 48, 7–43 (2014)

Green, A., Livanos, I.: Involuntary non-standard employment and the economic crisis: regional insights from the UK. Reg. Stud. 49(7), 1223–1235 (2015)

Hassink, M.: Regional resilience: a promising concept to explain differences in regional economic adaptability? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 3, 45–58 (2010)

Hincks, S., Webb, B., Wong, C.: Fragility and recovery: housing, localities and uneven spatial development in the UK. Reg. Stud. 48(11), 1842–1862 (2014)

Hudson, R.: Resilient regions in an uncertain world: wishful thinking or a practical reality? Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 3, 11–25 (2010)

Iammarino, S., Marinelli, E.: Education-job (mis)match and interregional migration: Italian university graduates’ transition to work. Reg. Stud. 49(5), 866–882 (2015)

Istat (1997) I Sistemi locali del lavoro 1991. Collana Informazioni no. 3. Rome: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica

Istat.: Atlante statistico dei comuni. Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, Rome (2006)

Kemeny, T., Storper, M.: Is specialisation good for regional economic development? Reg. Stud. 49(6), 1003–1018 (2015)

Lee, N.: Grim down south? The determinants of unemployment increases in British cities in the 2008–2009 recession. Reg. Stud. 48(11), 1761–1778 (2014)

Magrini, S., Gerolimetto, M., Duran, H.E.: Regional convergence and aggregate business cycle in the United States. Reg. Stud. 49(2), 251–272 (2015)

Manca, G., Attaway, D.F., Waters, N.: Program assessment and the EU’s agrienvironmental measure 214: an investigation of the spatial dynamics of agrienvironmental policies in Sardinia, Italy. Appl. Geogr. 50, 24–30 (2014)

Martin, R.: Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. J. Econ. Geogr. 12, 1–32 (2012)

Martin, R., Sunley, P.: Towards a developmental turn in evolutionary economic geography? Reg. Stud. 49(5), 712–732 (2015a)

Martin, R., Sunley, P.: On the notion of regional economic resilience: conceptualization and explanation. J. Econ. Geogr. 15(1), 1–42 (2015b)

McCann, P., Ortega-Argilés, R.: Smart specialization, regional growth and applications to European union cohesion policy. Reg. Stud. 49(5), 1291–1302 (2013)

Mulligan, G.: Revisiting interindustry employment requirements in nonmetropolitan economies. Lett. Sp. Resour. Sci. 3(2), 61–70 (2010)

Naito, T.: Urban-rural migration, unemployment, and privatization: a synthesis of Harris–Todaro model and a mixed duopoly. Lett. Sp. Resour. Sci. 5(2), 85–94 (2012)

Patacchini, E., Rice, P.G.: Geography and economic performance: exploratory spatial data analysis for Great Britain. Reg. Stud. 40, 1–20 (2007)

Patacchini, E.: Local analysis of economic disparities in Italy: a spatial statistics approach. Stat. Methods Appl. 17, 85–112 (2008)

Patacchini, E., Zenou, Y.: Spatial dependence in local unemployment rates. J. Econ. Geogr. 7, 169–191 (2007)

Pellegrini, G.: Proximity, polarization and local labour market performances. Netw. Sp. Econ. 2, 151–174 (2002)

Pike, A., Dawley, S., Tomaney, J.: Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 3, 59–70 (2010)

Proietti, T.: Convergence in Italian regional per-capita GDP. Appl. Econ. 37, 497–506 (2005)

Rice, P.G., Venables, A.J., Patacchini, E.: Spatial determinants of productivity: analysis for the regions of Great Britain. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 36, 727–752 (2006)

Rodríguez-Pose, A.: Do institutions matter for regional development? Reg. Stud. 47, 1034–1047 (2013)

Salvati, L.: The dark side of the crisis: disparities in per-capita income (2000–2012) and the urban-rural gradient in Greece. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie (2016). doi:10.1111/tesg.12203

Salvati, L., Mancini, A., Bajocco, S., Gemmiti, R., Carlucci, M.: Socioeconomic development and vulnerability to land degradation in Italy. Reg. Environ. Change 11, 767–777 (2011)

Salvati, L., Zitti, M., Carlucci, M.: Territorial systems, regional disparities and sustainability: economic structure and soil degradation in Italy. Sustainability 6, 3086–3104 (2014)

Salvati, L., Sateriano, A., Grigoriadis, E.: Crisis and the city: profiling urban growth under economic expansion and stagnation. Lett. Sp. Resour. Sci. 9(3), 329–342 (2016)

Sensier, M., Artis, M.: The resilience of employment in Wales: through recession and into recovery. Reg. Stud. 50, 586–599 (2014)

Serra, P., Vera, A., Tulla, A.F., Salvati, L.: Beyond urban-rural dichotomy: exploring socioeconomic and land-use processes of change in Spain (1991–2011). Appl. Geogr. 55, 71–81 (2015)

Simmie, J., Martin, R.: The economic resilience of regions: towards an evolutionary approach. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 3, 27–43 (2010)

Soares, J.O., Marques, M.L., Monteiro, C.F.: A multivariate methodology to uncover regional disparities: a contribution to improve European Union and governmental decisions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 145, 121–135 (2003)

Storper, M.: Why do regions develop and change? The challenge for geography and economics. J. Econ. Geogr. 11, 333–346 (2011)

Taulbut, M., Robinson, M.: The chance to work in Britain: matching unemployed people to vacancies in good times and bad. Reg. Stud. 49(12), 2070–2086 (2015)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salvati, L., Carlucci, M. & Venanzoni, G. Recession, resilience, local labour markets: wealthier is better?. Lett Spat Resour Sci 10, 177–204 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-016-0180-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12076-016-0180-8