Abstract

Background and aims

Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index is a HCC predictor in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients. However, little is known about whether FIB-4 helps identify non-cirrhotic CHB patients with minimal HCC risk after prolonged nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA) therapy.

Methods

A total of 1936 ethnically diverse, non-cirrhotic CHB patients were enrolled in this retrospective multi-national study. All patients received prolonged NA treatment, including entecavir and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. We explored whether FIB-4 cutoff of 1.30, a marker indicative of mild fibrosis severity, could stratify HCC risks in these patients.

Results

A total of 48 patients developed HCC after a mean follow-up of 6.98 years. FIB-4 level at 1 year after treatment (1-year FIB-4) was shown to be associated with HCC development and was superior to pre-treatment FIB-4 value. When patients were stratified by 1-year FIB-4 of 1.30, the high FIB-4 group was at an increased HCC risk compared to the low FIB-4 group, with a hazard ratio of 4.87 (95% confidence interval: 2.48–9.55). Multivariable analysis showed that sex and 1-year FIB-4 were independent predictors, with none of the 314 female patients with low 1-year FIB-4 developing HCC. Finally, 1-year FIB-4 of 1.30 consistently stratified HCC risks in patients with low PAGE-B score, a score composed of baseline age, sex and platelet count, and the annual incidence rate of HCC was 0.11% in those with PAGE-B < 10 + 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30.

Conclusions

In non-cirrhotic CHB patients receiving prolonged NA therapy, 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30 is useful for identifying those with minimal HCC risk by combining with female sex or low PAGE-B score.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global health problem and patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) are at risk of developing cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), resulting in over one million deaths per year [1]. Fortunately, prolonged nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA) treatment in CHB patients has been shown to minimize their liver-related complications and to reduce HCC risk [2,3,4,5,6].

HCC surveillance is important because early HCC detection is the key to lower HCC morbidity and mortality [7, 8]. Concerning all screening and surveillance programs, it is mandatory to create a cost-effective surveillance system. There is a need to identify subgroups of on-treatment patients who have a minimal HCC risk (< 0.2% per year) with less need of HCC surveillance, which may help physicians to prioritize the limited medical resources in the pandemic of COVID-19 [7, 8]. As HCC risk has been shown to remain substantial among the cirrhotic patients after NA therapy in contrast to the low risk of non-cirrhotic patients [3,4,5,6, 9,10,11,12,13], focusing on non-cirrhotic patients and exploring their factors to predict the minimal HCC risk is more feasible than including all the treated patients with heterogeneous severity of liver fibrosis to achieve the goal [9,10,11, 13,14,15].

Accumulating data show that liver fibrosis severity is a valid biomarker to predict HBV-related HCC development in non-cirrhotic patients after NA therapy [16]. Fibrosis index based on four factors (FIB-4) derived from routine clinical parameters has been recognized as a better surrogate marker for liver fibrosis severity in CHB compared to other biomarkers, such as AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) [17,18,19]. A recent large population-based cohort study suggested that FIB-4 < 1.30 was useful for identifying patients at low risk for liver-related events [20]. Our recent data also confirmed that FIB-4 of 1.29, a very similar cutoff, could identify CHB patients at low risk of cirrhosis and HCC in a treatment-naïve cohort and those at low HCC risk in a small on-treatment cohort [21, 22]. These data suggest that FIB-4 level around 1.29–1.30, a low cutoff to define mild liver fibrosis (F2 or less) [19], could be a useful marker to stratify the risk for future development of liver-related adverse events. However, it remains unclear whether the FIB-4 < 1.30 cutoff could accurately identify CHB patients who have sufficiently low HCC risk that the need for routine HCC surveillance can be mitigated after prolonged antiviral therapy.

To address this critical issue, using a FIB-4 based prediction model, we conducted an international, multicentre, retrospective cohort study with the primary aim of exploring whether it is possible to identify non-cirrhotic CHB patients with less need for routine HCC surveillance.

First, we investigated whether FIB-4 was a superior HCC predictor to APRI and whether FIB-4 determined at different time points was associated with different predicting performance. Second, we explored whether FIB-4 < 1.30 was associated with lower HCC risks than those with higher FIB-4 level. Finally, we investigated whether FIB-4 < 1.30 could help identify patients with minimal HCC risk by serving as a complementary predictor of sex and two HCC prediction models, including PAGE-B score, a Caucasian cohort-derived model based on pre-treatment age, sex, and platelet count [23, 24], and REACH-B score, an Asian-cohort derived model composed of age, sex, HBeAg, HBV DNA, and ALT [14, 25].

Materials and methods

Patient cohorts

This international, multicentre study was conducted across 5 hospital and clinic-based cohorts in Taiwan, South Korea, Greece, and the USA. Patients were enrolled between 2000 and 2016. They were included if they were > 18 years old, treatment-naïve, had chronic HBV mono-infection and were willing to receive prolonged entecavir or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate therapy. None of them had cirrhosis based on either liver histology (N = 208), liver stiffness measurement < 13 kPa (N = 67) [26], or characteristic ultrasonographic findings (n = 1661) [22, 27].

Supplementary Fig. 1 shows how we enrolled the patients retrospectively. Between 2007 and 2016, 2312 non-cirrhotic CHB patients were enrolled: 413 patients were from the National Taiwan University Hospital and Taipei Tzuchi hospital in Taiwan (TW1) [21], 393 from the China Medical University Hospital in Taiwan (TW2) [28], 817 from Asan Medical Center in South Korea (KR), 130 patients from General Hospital of Athens in Greece (GR), and 559 patients from Stanford University Medical Center and five other nearby community clinics in the USA (US) [29]. After excluding 93 patients without FIB-4 levels before treatment or at 1-year post-treatment and 5 with follow-up period less than 1 year, 2214 patients remained. Another 273 patients with HBV DNA level < 2000 IU/mL or unavailable HBV DNA level before antiviral treatment and 5 patients with HCC diagnosed within the first year of follow-up were excluded. Finally, a total of 1936 patients were included for subsequent analyses.

During the treatment period, entecavir was shifted to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate at the physician’s discretion when viral suppression was suboptimal.

This study was approved by the research ethics committees of each participating center.

Data collection

Patients were tested for serological markers, including HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe), hepatitis C antibody (anti-HCV), and had liver function tests before antiviral treatment. Throughout the follow-up period, serum liver function tests were assayed every 3 to 6 months. HBV DNA levels with or without alpha-fetoprotein levels were determined every 6 to 12 months and abdominal ultrasonography was performed about every 6 months for HCC surveillance.

Diagnosis of HCC

HCC was diagnosed either by histology/cytology or by typical imaging findings (arterial enhancement and venous wash-out by contrast-enhanced computerized tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scanning) in hepatic nodules larger than 1 cm [30].

Serological assays

Serum HBsAg, HBeAg, anti-HBe, and anti-HCV were tested using commercial assays. Serum HBV DNA level was quantified using the commercial assays available at each hospital with lower detection limits ranging from 20 to 100 IU/mL.

Calculation of FIB-4 index and APRI

The FIB-4 index and APRI were calculated according to the formulas:

FIB-4 = age (years) × AST [U⁄L] ⁄(platelet counts [109⁄ L] × (ALT [U⁄L])1⁄2). APRI = AST level (/upper limit of normal of AST)/ platelet counts [109⁄L] × 100 [19]. The upper limit of normal AST is 40 U/L.

Statistical analysis

HCC was defined as the endpoint. The clinical follow-up started at the time of starting antiviral treatment. The person-years were censored on the date of HCC development, death, the last date of follow-up, or Dec 31, 2018, whichever came first. The cumulative incidence of HCC stratified by different variables was derived using the Kaplan–Meier curve analysis and the log-rank test was used to test for the statistical difference.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to compute the area under the ROC curves (AUROC) for different factors and FIB-4 determined at different time-points in predicting HCC development.

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for continuous variables and percentages were used for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards regression model was adopted to calculate the crude and multivariate-adjusted hazard ratios (HR) of HCC. Covariates in multivariable analysis were chosen according to stepwise regression model with significance level = 0.10 for removal from the model and significance level = 0.05 for addition to the model. Statistical significance of all tests was defined as p < 0.05 by two-tailed tests. All analyses were performed using Stata statistical software (version 10.0; Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Pre-treatment characteristics and follow-up data of 1936 non-cirrhotic CHB patients with prolonged NA treatment

Table 1 shows the pre-treatment characteristics of 1936 treatment-naïve patients. Most of them were males and of Asian descent. The median age at enrolment was 45.64 years. The median HBV DNA level and platelet count before treatment were 6.54 (log10 IU/mL) and 187 (109/L), respectively. Most of the patients had ALT > 40 U/L (88.38%) before treatment but most also had improvement to < 40 U/L after one year of treatment (78.41%).

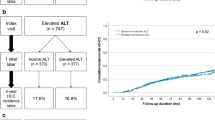

The mean follow-up period was 6.99 ± 2.40 years. During the follow-up, 48 patients developed HCC yielding an annual incidence rate of 0.35% (95% CI 0.27–0.47%) (Fig. 1a).

Comparing the FIB-4 and APRI in predicting HCC development

The pre-treatment median values (interquartile range) of FIB-4 and APRI were 1.67 (1.65) and 1.03 (1.59), respectively. We first explored which marker serves as a better HCC predictor by comparing the AUROCs of both markers in the overall cohort. The results showed pre-treatment FIB-4 had better prediction accuracy than APRI [AUROC: 0.62 (95% CI 0.54–0.69) vs. 0.51 (95% CI 0.44–0.58), p < 0.001], but both performed relatively poorly.

Comparing the FIB-4 levels at different time points in predicting HCC development

We then analyzed the FIB-4 kinetics in 1712 individuals with FIB-4 available at different time points. FIB-4 level was the highest before treatment and dropped during the first year of therapy, then remained constant thereafter (Suppl. Fig. 2).

To ascertain at what time point in the treatment course FIB-4 would have the optimal predictive performance, FIB-4 levels at pre-treatment, 1 year and 2 years post-treatment were calculated in 1726 patients who did not develop HCC within the first 2 years of follow-up and their AUROCs in predicting HCC development were compared. We found that FIB-4 at 1 year after treatment [AUROC: 0.75 (95% CI 0.67–0.82)] was superior to pre-treatment FIB-4 [AUROC: 0.64 (95% CI 0.56–0.71), p = 0.003] and might be better than that at 2 years after treatment [AUROC: 0.69 (95% CI 0.60–0.77), p = 0.040] (Fig. 1b). Given this, FIB-4 at 1-year post-treatment (1-year FIB-4) was selected as our HCC prediction marker.

Risk factors associated with HCC development

Different FIB-4 cutoffs have been reported to be clinically useful in patients with chronic HBV infection. We compared the prediction performance using the Youden index among different FIB-4 cutoffs once reported for predicting significant liver fibrosis in a meta-analysis [19] and HCC development [21, 31,32,33], in patients with chronic HBV infection (supplementary Table 1). Among all the 8 cutoffs of 1-year FIB-4, the optimal one was around 1.30–1.45. We decided to choose 1.30 as it is a well-validated cutoff in 2 large cohort studies [20, 21]. The AUROC, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for the cutoff to predict HCC development were 0.68, 77.1%, 58.3%, 4.5%, and 99% respectively.

We then explored whether 1-year FIB-4 of 1.30 is an optimal cutoff for stratifying HCC risks. When categorizing the patients with this cutoff, we found that the high FIB-4 group, compared to the low FIB-4 group, had an increased HCC risk with HR of 4.87 (95% CI 2.48–9.55, p < 0.001) in univariable analysis (Fig. 1c and Table 2). Older age and male sex were also associated with increased HCC risks with HR of 1.06 per 1-year increase (95% CI 1.03–1.08, p < 0.001) and 3.91 (95% CI 1.55–9.88, p = 0.004, Fig. 1d), respectively (Table 2).

In multivariable analysis, older age, male sex, and 1-year FIB-4 > 1.30 were independently associated with HCC development (Table 2). However, since age has been incorporated in the FIB-4 calculation, we only stratified our subsequent analyses by sex and 1-year FIB-4 (supplementary Table 2). By 1-year FIB-4, the annual HCC incidence in patients with 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30 was 0.14% (95% CI 0.08–0.25%). By 1-year FIB-4 and sex, none of the 314 women with 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30 developed HCC during the mean follow-up period of 7.01 years (Supplementary Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis of enrolling patients with ETV treatment and patients with undetectable viral load after treatment for 1 year

As different antiviral drugs could be associated with different HCC risks, sensitivity analysis was performed by enrolling 1386 patients receiving ETV treatment only. The 1-year FIB-4 > 1.30 was consistently associated with increased HCC risks and the age- and sex-adjusted HR was 4.92 (95% CI 1.81–13.34).

We also explored the role of FIB-4 in patients with undetectable viral load after treatment for 1 year. In 771 patients with available HBV DNA levels at 1 year after treatment, 578 patients (75.0%) cleared serum HBV DNA and 12 patients developed HCC. One-year FIB-4 of 1.30 consistently stratified the HCC risk in patients with undetectable viral load [High vs. low, HR: 12.5 (95% CI 1.6–96.8)].

One-year FIB-4 complemented pre-treatment PAGE-B score to stratify HCC risks

We confirmed a positive correlation between PAGE-B score and HCC risks (p for trend < 0.001) with an AUROC of 0.67 (95% CI 0.60–0.75) for HCC prediction. When stratifying the patients by PAGE-B scores of 10 and 17, there were 1065, 859, and 12 patients with PAGE-B score < 10 (low score), between 10–17 (intermediate score), and > 17 (high score), respectively. The 5-year cumulative HCC incidence rates were 0.86% and 2.18% for the low and intermediate PAGE-B score, respectively (Supplementary Table 3). Patients with intermediate score had higher HCC risk with HR of 3.01 (95%: 1.61–5.62, p = 0.001) when compared to patients with low PAGE-B score (Supplementary Table 3). The subgroup with high PAGE-B scores was not analyzed due to the small patient number.

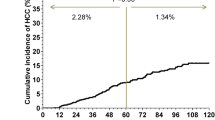

As PAGE-B score is a pre-treatment prediction model, we explored whether 1-year FIB-4 predicted HCC in patients with different pre-treatment PAGE-B scores (Supplementary Table 3). Among patients with low and intermediate PAGE-B scores, those with higher FIB-4 had higher HCC incidence in both groups (Fig. 2a, b). The HR (high vs. low FIB-4 level) was 5.10 (95% CI 1.79–14.54, p = 0.002) and 2.89 (95% CI 1.02–8.24, p = 0.047) in the low and intermediate groups, respectively.

The HCC risk was explored in the patients stratified by different levels of pre-treatment PAGE-B score and 1-year FIB-4 (Supplementary Table 3). In the 888 patients who had pre-treatment PAGE-B score < 10 and 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30, their annual incidence rate of HCC was 0.11% (95% CI 0.05–0.23%).

One-year FIB-4 served as an HCC predictor independent of REACH-B score

REACH-B score was also calculated and the median (IQR) score was 11 (11). A higher REACH-B score was shown to be associated with increased HCC risk (p for trend < 0.001) with AUROC of 0.69 (95% CI 0.63–0.76) for HCC prediction. One-year FIB-4 > 1.30 consistently served as an independent HCC predictor with REACH-B score-adjusted HR of 3.40 (95% CI 1.64–7.06).

Discussion

A major complication in non-cirrhotic CHB patients after initiating prolonged NA is the development of HCC, but it has been a challenge to precisely predict HCC risk in these patients due to their low HCC incidence, hence a large cohort study with long-term follow-up is required. This multi-center cohort study, including 1936 non-cirrhotic patients from Asia, Europe, and the USA, is the first report to show that 1-year FIB-4 of 1.30, a published cutoff for mild fibrosis severity [19], was effective in stratifying HCC risks. More importantly, 1-year FIB-4 of 1.30 complemented sex, pre-treatment PAGE-B score, and pre-treatment REACH-B score to stratify HCC risks, implying 1-year FIB-4 may be a useful marker to categorize HCC risks in non-cirrhotic CHB patients receiving prolonged NA therapy.

In addition, our data showed that none of the 314 women with 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30 developed HCC within a mean follow-up period of 7.01 years. The annual HCC incidence was 0.11% (95% CI 0.05–0.23%) in 888 patients with pre-treatment PAGE-B < 10 and 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30 with 95% confidence interval just above the recommended threshold (0.2% per year) for HCC surveillance. Taking these data together, 1-year FIB-4 could help practicing physicians identify patients with minimal HCC risks with less need for routine HCC surveillance. Moreover, the FIB4 is based on readily available factors and can be applicable in resource-limited areas where most HBV patients of the world live in. Our finding is important in HBV management as these areas do not have resources to survey all CHB patients for HCC. However, further large prospective studies are needed to confirm our findings.

We found 14 patients who developed HCC with a low PAGE score (TW1: 4, KR: 4, GR: 1, US: 5) with 5-year cumulative incidence of 0.86%, which was contradictory to the zero HCC risk as reported in the Caucasian cohort [23, 24]. The discrepancy may be reasoned by our larger cohort with different ethnicities. Our data suggested that the combination of 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30 with a low PAGE-B score could serve as a better predictor to define low HCC risk. With further validation, it would be possible to identify a group of patients with less need for HCC surveillance, which is important for us prioritize medical resources in the pandemic of COVID-19.

Our study has several strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to include nearly 2000 multiethnic non-cirrhotic CHB patients receiving prolonged NA therapy. A large cohort with a long follow-up period is the mainstay to address the issue of HCC surveillance due to the very low HCC incidence in the non-cirrhotic, NA-treated patients. Second, previous studies have shown that either FIB-4 or APRI values are often inflated before antiviral therapy in patients with active hepatitis due to elevated AST and ALT levels [34]. A rapid decrease of AST and ALT values following antiviral treatment can generally be expected and are largely due to resolution of liver necroinflammation rather than liver fibrosis improvement. Inflated FIB-4 values tend to be unstable, and may not predict HCC development. Our data also showed 1-year FIB-4 predicted HCC development more accurately than pre-treatment FIB-4 levels. In addition, the prediction performance also improved using 1-year APRI (data not present). Both of the findings support the inference and suggest these biomarkers are useful when determined 1 year after treatment.

Our study also has some limitations. First, liver stiffness measurement was not available in every hospital at enrolment. The diagnosis of non-cirrhosis was mostly made by abdominal ultrasonography, which was not perfect. In addition, we could not compare the prediction power between liver stiffness value and FIB-4. However, liver stiffness measurement is not routinely performed in most real-world settings outside of tertiary referral centers, whereas FIB-4 and PAGE-B could be more useful as both are based on readily available clinical parameters even in most resource-limited areas. Second, the number of non-Asian patients (N = 117, around 6%) and those receiving TDF (N = 210, around 10%) were small. The clinical utility needs to be further validated in these patients. Thirdly, several host risk factors, such as obesity and diabetes, and possible viral risk factors, such as HBsAg, hepatitis B core-related antigen levels, and HBV DNA kinetic, were not included in our analysis because these data were not collected routinely. Finally, we did not explore the role of FIB-4 in other prediction models containing cirrhosis as a major predictor since we aimed to identify minimal HCC risk group and focused on non-cirrhotic patients only [9, 35,36,37].

In summary, in non-cirrhotic CHB patients receiving prolonged NA treatment from different countries, 1-year FIB-4 of 1.30 is useful for stratifying HCC risk in such patients. Patients with 1-year FIB-4 < 1.30 have a low HCC risk by combining with female sex or low PAGE-B score, which paves the way to prioritize the limited medical resources, such as HCC surveillance, in the pandemic of COVID-19.

Abbreviations

- APRI:

-

AST to platelet ratio index

- FIB-4:

-

Fibrosis index based on four factors

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- NA:

-

Nucleos(t)ide analogue

- CHB:

-

Chronic hepatitis B

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- ULN:

-

Upper limit of normal

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- HBeAg:

-

Hepatitis B e antigen

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- AUROC:

-

Area under the ROC curve

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

References

Tseng TC, Kao JH. Elimination of hepatitis B: is it a mission possible? BMC Med. 2017;15:53.

Nguyen MH, Yang HI, Le A, Henry L, et al. Reduced incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with chronic hepatitis B treated with tenofovir-a propensity score-matched study. J Infect Dis. 2019;219:10–8.

Wong GL, Chan HL, Mak CW, Lee SK, et al. Entecavir treatment reduces hepatic events and deaths in chronic hepatitis B patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2013;58:1537–47.

Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521–31.

Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, Seko Y, et al. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2013;58:98–107.

Su TH, Hu TH, Chen CY, Huang YH, et al. Four-year entecavir therapy reduces hepatocellular carcinoma, cirrhotic events and mortality in chronic hepatitis B patients. Liver Int. 2016;36:1755–64.

Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, Chang KM, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018;67:1560–99.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol 2017;67:370-398

Yang HI, Yeh ML, Wong GL, Peng CY, et al. REAL-B (Real-world Effectiveness from the Asia Pacific Rim Liver Consortium for HBV) risk score for the prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with oral antiviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2019

Tseng TC, Peng CY, Hsu YC, Su TH, et al. Baseline Mac-2 binding protein glycosylation isomer level stratifies risks of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients with oral antiviral therapy. Liver Cancer. 2020;9:207–20.

Hsu YC, Jun T, Huang YT, Yeh ML, et al. Serum M2BPGi level and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after oral anti-viral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48:1128–37.

Chiang HH, Lee CM, Hu TH, Hung CH, et al. A combination of the on-treatment FIB-4 and alpha-foetoprotein predicts clinical outcomes in cirrhotic patients receiving entecavir. Liver Int. 2018;38:1997–2005.

Tada T, Kumada T, Toyoda H, Tsuji K, Hiraoka A, Tanaka J. Impact of FIB-4 index on hepatocellular carcinoma incidence during nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B: an analysis using time-dependent receiver operating characteristic. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:451–8.

Jung KS, Kim SU, Song K, Park JY, et al. Validation of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma prediction models in the era of antiviral therapy. Hepatology. 2015;62:1757–66.

Wang HW, Lai HC, Hu TH, Su WP, et al. Stratification of hepatocellular carcinoma risk through modified FIB-4 index in chronic hepatitis B patients on entecavir therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:442–9.

Wong VW, Janssen HL. Can we use HCC risk scores to individualize surveillance in chronic hepatitis B infection? J Hepatol. 2015;63:722–32.

Mallet V, Dhalluin-Venier V, Roussin C, Bourliere M, et al. The accuracy of the FIB-4 index for the diagnosis of mild fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:409–15.

Kim BK, Kim DY, Park JY, Ahn SH, et al. Validation of FIB-4 and comparison with other simple noninvasive indices for predicting liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in hepatitis B virus-infected patients. Liver Int. 2010;30:546–53.

Xiao G, Yang J, Yan L. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index and fibrosis-4 index for detecting liver fibrosis in adult patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2015;61:292–302.

Unalp-Arida A, Ruhl CE. Liver fibrosis scores predict liver disease mortality in the United States population. Hepatology. 2017;66:84–95.

Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Su TH, Yang WT, et al. Fibrosis-4 index helps identify hbv carriers with the lowest risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1564–74.

Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Su TH, Yang WT, et al. Fibrosis-4 index predicts cirrhosis risk and liver-related mortality in 2075 patients with chronic HBV infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:1480–9.

Papatheodoridis G, Dalekos G, Sypsa V, Yurdaydin C, et al. PAGE-B predicts the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis B on 5-year antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2016;64:800–6.

Papatheodoridis GV, Idilman R, Dalekos GN, Buti M, et al. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma decreases after the first 5 years of entecavir or tenofovir in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2017;66:1444–53.

Yang HI, Yuen MF, Chan HL, Han KH, et al. Risk estimation for hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B (REACH-B): development and validation of a predictive score. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:568–74.

Friedrich-Rust M, Ong MF, Martens S, Sarrazin C, et al. Performance of transient elastography for the staging of liver fibrosis: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:960–74.

Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang HC, Chen CL, et al. Higher proportion of viral basal core promoter mutant increases the risk of liver cirrhosis in hepatitis B carriers. Gut. 2015;64:292–302.

Chen CH, Lee CM, Lai HC, Hu TH, et al. Prediction model of hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B treated with entecavir. Oncotarget. 2017;8:92431–41.

Hsu YC, Wong GL, Chen CH, Peng CY, et al. Tenofovir versus entecavir for hepatocellular carcinoma prevention in an international consortium of chronic hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol 2019

Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:358–80.

Suh B, Park S, Shin DW, Yun JM, et al. High liver fibrosis index FIB-4 is highly predictive of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B carriers. Hepatology. 2015;61:1261–8.

Honda M, Shirasaki T, Terashima T, Kawaguchi K, et al. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) core-related antigen during nucleos(t)ide analog therapy is related to intra-hepatic HBV replication and development of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Infect Dis. 2016;213:1096–106.

Kim JH, Kim JW, Seo JW, Choe WH, Kwon SY. Noninvasive tests for fibrosis predict 5-year mortality and hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:882–8.

Kim WR, Berg T, Asselah T, Flisiak R, et al. Evaluation of APRI and FIB-4 scoring systems for non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2016;64:773–80.

Yuen MF, Tanaka Y, Fong DY, Fung J, et al. Independent risk factors and predictive score for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:80–8.

Wong VW, Chan SL, Mo F, Chan TC, et al. Clinical scoring system to predict hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1660–5.

Hsu YC, Yip TC, Ho HJ, Wong VW, et al. Development of a scoring system to predict hepatocellular carcinoma in Asians on antivirals for chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2018;69:278–85.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues at the National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, who enrolled and followed the patients, and all the research assistants, including Miss Wan-Ting Yang and Mr. Cheng-Hsueh Tsai, who assisted in collection of clinical information. Finally, we thank the Cancer Registry, Cancer Administration and Coordination Center, NTUH for providing cancer registration data to confirm our diagnoses.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from National Taiwan University Hospital (107-N4041, 108-N4157, and 109-N4644), the Ministry of Science and Technology, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (MOST 106–2314-B-002–136), and National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX108-10807BC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: T-CT, J-HK. Acquisition of data: T-CT, C-CW, MHN, HT, CHW, CLW, JZ, JL, MP, GP, J.C., Y-S.L., C-Y. P., H-C. L. Analysis and interpretation of data: T-CT. J-HK. Drafting of the manuscript: T-CT, J-HK. Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: J-HK, MHN, MP, GP, JC, Y-SL. Statistical analysis: T-CT. Obtained funding: TCT, J-HK. Technical or material support: TCT. Study supervision: J-HK.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J-H. K. has served as a consultant for Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Roche and on speaker’s bureaus for Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp and Dohme. T-C. T. has served on speaker’s bureaus for Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Gilead Sciences. Y-S.L. is an advisory board member of Gilead Sciences and receives investigator-sponsored research funding from Gilead Sciences. GP has served as advisor and/or lecturer for Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dicerna, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Ipsen, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Spring Bank and has received research grants Abbvie, Bristol- Myers Squibb, Gilead. C-Y. P. has served as an advisory committee member for Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp and Dohme, and Roche. Mindie H. Nguyen has served as a consultant or in the advisory board for Spring Bank, Novartis, Gilead, Anylam, Intercept, Exact Sciences, Laboratory of Advanced Medicine and has received grant/research support from Gilead, Pfizer, Vir, National Cancer Institute, B. K. Kee Foundation and Glycotest.

Ethical statement

Our research complies with the guidelines for human studies and has been conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All the data collection and analysis of this retrospective cohort study has been approved by the research ethical committees of each hospital.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12072_2020_10124_MOESM2_ESM.tiff

Supplementary Figure 2. FIB-4 kinetic of 1712 on-treatment CHB patients with available FIB-4 levels at different time points (TIFF 117 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tseng, TC., Choi, J., Nguyen, M.H. et al. One-year Fibrosis-4 index helps identify minimal HCC risk in non-cirrhotic chronic hepatitis B patients with antiviral treatment. Hepatol Int 15, 105–113 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-020-10124-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-020-10124-z