Abstract

Chronic inflammation is supposed to be an important mediator of cardiometabolic dysfunctions seen in type 2 diabetes. In this mini-review, we collected evidence (PubMed) from randomized controlled trials (through March 2016) evaluating the effect of anti-inflammatory drugs on indices of glycemic control and/or cardiovascular events in people with type 2 diabetes. Within the last 25 years, many anti-inflammatory drugs have been tested in type 2 diabetes, including hydroxychloroquine, anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies (etanercept and infliximab), salsalate, interleukin-1 antagonists (anakinra, canakinumab, gevokizumab, LY2189102), and CC-R2 antagonists. Despite being promising, the observed effects on HbA1c or glucose control remain rather modest in most clinical trials, especially with the new drugs. There are many trials underway with anti-inflammatory agents to see whether patients with cardiovascular diseases and/or type 2 diabetes may have clinical benefit from marked reductions in circulating inflammatory markers. Until now, a large trial with losmapimod (a p38 inhibitor) among patients with acute myocardial infarction, including one/third of diabetic patients, showed no reduction in the risk of major ischemic cardiovascular events. Further evidence is warranted in support of the concept that targeting inflammation pathways may ameliorate glycemic control and also reduce cardiovascular complications in type 2 diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

At the end of the last century, Hotamisligil and Spiegelman [1, 2] opened the way to the inflammation–insulin resistance connection. They demonstrated the presence of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) in adipose tissue and its direct role in inducing insulin resistance in mice. This link has represented more than an interesting hypothesis in Medicine, given that many metabolic conditions, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes, are thought to be states of chronic inflammation. Needless to say, all these metabolic abnormalities are strictly tied together, which gave further support to the concept of a “common soil” linking chronic inflammation to metabolic disorders. Visceral obesity was thought to be the starting condition through the release of inflammatory cytokines, including TNF, which may facilitate insulin resistance and possibly hyperglycemia in predisposed people. The last, but not the least, part of the inflammatory circle came from the evidence that increased inflammatory activity plays a critical role in the development of atherogenesis and predispose-established atherosclerotic plaques to rupture [3]. Therefore, chronic inflammation was supposed to be an important mediator of cardiometabolic dysfunctions seen in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes [4].

Cardiometabolic benefit of reducing inflammation in type 2 diabetes

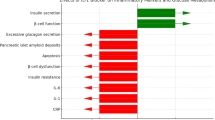

After more than 20 years from those seminal studies [1, 2], what does it remain of the inflammatory hypothesis of metabolic diseases, particularly of type 2 diabetes? The hypothesis has been explored in humans mainly by targeting inflammation with specific drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes; as supporting observations, studies in people with inflammatory rheumatoid diseases have also been performed. In a general perspective, the inflammatory connection of type 2 diabetes should be satisfied when specific interventions (a) reduce the circulating inflammatory markers; (b) ameliorate the glycemic control of diabetes, via an improvement of insulin resistance, insulin secretion or both; and (c) decrease cardiovascular events.

In this narrative review, we collected evidence coming from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that assessed the effect of anti-inflammatory drugs on indices of glycemic control (glucose, HbA1c) and/or cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes. We identified relevant studies through an extensive literature search in MEDLINE through March 2016, with the following terms: type 2 diabetes, noninsulin-dependent diabetes, anti-inflammatory drugs, cardiovascular outcomes, clinical trial, and glycemic control. No language restrictions were imposed. Reference lists of original studies, and previous reviews were also carefully examined.

Anti-inflammatory drugs and glycemic control

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)

HCQ exerts its action through many mechanisms, including inhibition of phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and chemotaxis, and by decreasing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases, and blocking T and B cell receptors, and toll-like receptor signaling [5, 6]. In addition, HCQ has been suggested to have beneficial effect on lipids, coagulation, and diabetes which may contribute to lower the high cardiovascular risk in Systemic Lupus patients. We found three randomized trials [7–9] lasting 6–18 months, with a double-blind procedure in two [7, 9], assessing the role of HCQ in insulin-resistant, treatment refractory (insulin, sulfonylurea, or both)-patients with type 2 diabetes (Table 1). The results were satisfactory or very satisfactory as the HbA1c response was similar to that seen with other antidiabetic agents, like pioglitazone [9], or ranged from 1 to 3 % decrease in HbA1c in a way similar to that of insulin [7].

Interestingly, the use of HCQ in rheumatoid arthritis has been associated with a decreased risk of developing diabetes: 77 % reduced risk among those taking the drug for more than 4 years, compared to those who had not taken it [10]. Moreover, in a retrospective cohort of 1266 patients with rheumatoid arthritis from 2001 to 2013 [11], treatment with HCQ was independently associated with a 72 % reduction in all incident cardiovascular (CV) events.

Anti-TNF therapies

Anti-TNF therapies, using the TNF receptor:Fc fusion protein (etanercept) or specific monoclonal antibodies (infliximab), are widely used in various inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [12], psoriasis [13], and Crohn’s disease [14]. The various studies performed until now with the aim to obtain amelioration of insulin resistance and hence hyperglycemia by blocking the TNF system yielded negative results not only in people with type 2 diabetes [15, 16] (Table 1), but also in nondiabetic, insulin-resistant subjects [17]. The absence of any consistent effect on insulin sensitivity by anti-TNF therapies has been disappointing, considering that the whole story started from the hypothesis that TNF could be a major mediator of insulin resistance. More or less convincing reasons have been put forward to explain these negative results, including dosing duration, choice of population, the presence of more powerful determinants of insulin sensitivity, or a dissociation between TNF-mediated effects on inflammation and insulin resistance in humans. As it happened with the lack of benefit of anti-TNF therapy for heart failure [18], the TNF hypothesis for type 2 diabetes is not supported by the results of specific studies.

In a retrospective cohort study of 47,193 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the risk of acute myocardial infarction was elevated by 30 % among anti-TNF initiators overall (etanercept and infliximab) compared with abatacept or tocilizumab initiators [19].

Salsalate

More than a century ago, high doses of sodium salicylate (≥5 g/d) were first demonstrated to alleviate symptoms in diabetic patients having presumably type 2 diabetes [20], as Ebstein in 1876 and then Williamson in 1901 concluded that sodium salicylate could diminish greatly the sugar excretion. Salsalate, which has been used to treat inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and other rheumatologic conditions, is a strong inhibitor of the NF-κB pathway [21]. Salicylates have been shown to inhibit IκB kinase, thereby inhibiting the NF-κB cascade and decreasing the production of inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-6, TNF, and CRP) and decreasing insulin resistance [22].

As demonstrated in recent trials (Table 1), the use of salsalate therapy, at doses of 3–4.5 g daily, has the ability to lower insulin resistance and reduce the levels of glucose, triglycerides, and free fatty acid concentrations, with minimal side effects [23, 24]. The two RCTs with salsalate demonstrated a benefit of 0.33 % HbA1c in type 2 diabetes compared with placebo, but they failed to have improvements in endothelium-dependent and -independent dilations of the brachial artery [25]. Unlike aspirin, salsalate is not acetylated, it is not a cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor and does not impact upon bleeding times or platelet aggregation. Whether or not salsalate might reduce cardiovascular event rates is unknown.

Interleukin-1 antagonism

Under the influence of higher glycemic levels, islets macrophages start to produce inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, which contributes to the impairment in pancreatic secretory function by increasing the β-cell apoptosis rate [26].

Anakinra is a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, the first to be used in clinical practice. The first study [27] that tested the metabolic effect of IL-1β inhibition with Anakinra in type 2 diabetes reported benefits on both hyperglycemia and secretory function of insulin associated with reduced C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (Table 1). Additional 12 independent clinical studies [28] have demonstrated that IL-1 antagonism has the potential to improve glycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. However, the magnitude of the effects is often a matter of debate.

Canakinumab binds to human IL-1β, blocking interaction of this cytokine with its receptors, an effect that should in turn reduce circulating levels of IL-6 and hepatic production of CRP and fibrinogen [29]. In a phase IIb, randomized trial (556 men and women) [30], monthly doses of canakinumab over 4 months had a modest but nonsignificant effect on HbA1c and glucose, with no effect on lipids (LDL and HDL cholesterol) among the well-controlled (baseline HbA1c = 7.4 %) diabetic patients being at high risk of cardiovascular disease (Table 1). Yet, in this same study population, canakinumab was highly effective at reducing CRP, IL-6, and fibrinogen levels.

Gevokizumab is a recombinant human-engineered monoclonal antibody that binds and neutralizes human IL-1β. In a placebo-controlled study [31], a total of 98 patients were randomly assigned to placebo (17 subjects) or gevokizumab (81 subjects). In the combined intermediate-dose group (single doses of 0.03 and 0.1 mg/kg), the mean placebo-corrected decrease in glycated hemoglobin was 0.85 % after 3 months (N = 16 subjects, P = 0.049) (Table 1), along with enhanced C-peptide secretion, increased insulin sensitivity, and a reduction in CRP levels.

LY2189102 is a humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG4) that binds to IL-1β with high affinity and neutralizes its activity. In a phase II, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study [32], subcutaneous LY2189102 administered weekly for 12 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes reduced HbA1c levels at 12 weeks (−0.38 % with the 18 mg dose) and inflammatory biomarkers, including CRP and IL-6 (Table 1).

CC-R2 antagonists

C–C chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) also known as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, and its receptor, C–C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2), play important roles in various inflammatory diseases. In a 4-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and randomized, multicenter study [33], 89 patients were randomized to receive either 250- or 1000-mg of JNJ-41443532, an orally bioavailable, selective, reversible antagonist of CCR CCR2 antagonist, twice daily; 30-mg of pioglitazone once daily (reference arm); or placebo. There was a modest yet significant decrease in 23-h-weighted mean glucose (Table 1).

Anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular outcomes

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration [34] was a meta-analysis of individual records from 160,309 people without history of vascular disease from 54 long-term prospective studies; the study found a positive association between CRP and vascular risk, at the same level of that associated with an increase in either blood pressure or cholesterol. Despite the robust epidemiological evidence, it remains unknown whether inhibition of inflammation per se will lower vascular event rates. Moreover, the optimal agent for trials testing the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerosis should be able to reduce inflammatory biomarkers, such as CRP, IL-6, and fibrinogen, with minimal effects on lipids and other CV risk factors.

There is a great expectation from the results of Canakinumab Antiinflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS) as regards whether patients with cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes may benefit from an anti-IL-1β treatment [35]. The declared aim of CANTOS was to address directly the potential for canakinumab to reduce incident cardiovascular events in a secondary prevention population with a persistent proinflammatory response. Another NHLBI-sponsored trial (Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial—CIRT) is evaluating the role of low-dose methotrexate as a potential anti-inflammatory agent to suppress cardiovascular event rates [36]. Moreover, large-scale Phase III trials are now underway with agents that lead to marked reductions in IL-6 and CRP (such as canakinumab and methotrexate), as well as with agents that impact on diverse non-IL-6-dependent pathways, disrupting the first step of the arachidonic acid pathway of inflammation through the inhibition of the phospholipase A2 (such as varespladib and darapladib) [37].

In the meantime, a trial with losmapimod, a selective, reversible, competitive inhibitor of p38 MAPK with onset as early as 30 min after oral dosing has come to an end [38]. Activation of p38 MAPK leads to amplification of the inflammatory cascade through enhanced production of multiple cytokines, including TNF, IL-1, and IL-6, metalloproteinases, and cyclooxygenase. This large RCT was prompted by the findings of a randomized trial of 526 patients hospitalized with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), in which losmapimod, administered prior to percutaneous coronary intervention, attenuated the acute increase in markers of inflammation (CRP and IL-6) at 72 h [39].

In the LATITUDE-TIMI 60 [38], patients were randomized to either twice-daily losmapimod (7.5 mg; n = 1738) or matching placebo (n = 1765) and were treated for 12 weeks and followed up for an additional 12 weeks. Among patients with acute myocardial infarction, the use of losmapimod compared with placebo did not reduce the risk of major ischemic cardiovascular events, although it reduced levels of CRP at 4 weeks and at the end of the treatment period at 12 weeks. The trial included one/third (33 %) of diabetic patients in each arm.

Conclusions

There is a considerable increase in the interest among the researchers about anti-inflammatory therapies in the setting of chronic disorders such as type 2 diabetes and CV diseases. However, because inflammation acts along multiple and redundant pathways, the identification of an appropriate target may be difficult. The current interest is apparently directed toward new drugs targeting inflammation which are innovative molecules acting at different stages of the inflammatory cascade. It has been hypothesized that the immune system is intimately linked to metabolism disorders [40]: accordingly, patients with diabetes may benefit from IL-1β or TNF blockade which focuses on pathologically activated pathways responsible for the disease. However, this hypothesis has to be confirmed by further studies specifically designed to test the effect of immune-modulating drugs on diabetes and the associated CV risk. Paradoxically, the drugs that until now have demonstrated the more robust effect on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes are the oldest ones, such as HQC and salsalate. HCQ has the most abundant evidence for metabolic benefit, with the longest trial so far performed and the largest number of patients. The newer, costly, and innovative drugs have yet to demonstrate their value in both metabolic and CV outcomes in type 2 diabetic patients. The old, cheap medications could be a useful and cost-efficient option in the treatment of specific individuals with treatment-refractory type 2 diabetes; however, larger and longer clinical trials are needed to convince the medical community of their benefits on treatment and prevention of type 2 diabetes, as well as on its CV complications.

References

G.S. Hotamisligil, N.S. Shargill, B.M. Spiegelman, Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science 259, 87–91 (1993)

G.S. Hotamisligil, A. Budavari, D. Murray, B.M. Spiegelman, Reduced tyrosine kinase activity of the insulin receptor in obesity-diabetes: central role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Clin. Investig. 94, 1543–1549 (1994)

P. Libby, Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 420, 868–874 (2002)

K. Esposito, D. Giugliano, The metabolic syndrome and inflammation: association or causation? Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 14, 228–232 (2004)

C. Belizna, Hydroxychloroquine as an anti-thrombotic in antiphospholipid syndrome. Autoimmun. Rev. 14, 358–362 (2015)

Y.C Kaplan, J. Ozsarfati, C. Nickel, G. Koren, Reproductive outcomes following hydroxychloroquine use for autoimmune diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. (2015 Dec 23). doi: 10.1111/bcp.12872. [Epub ahead of print]

A. Quatraro, G. Consoli, M. Magno et al., Hydroxychloroquine in decompensated, treatment-refractory noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. A new job for an old drug? Ann. Intern. Med. 112, 678–681 (1990)

H.C. Gerstein, K.E. Thorpe, D.W. Taylor, R.B. Haynes, The effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are refractory to sulfonylureas—a randomized trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 55, 209–219 (2002)

A. Pareek, N. Chandurkar, N. Thomas et al., Efficacy and safety of hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a double blind, randomized comparison with pioglitazone. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 30, 1257–1266 (2014)

M.C. Wasko, H.B. Hubert, V.B. Lingala, J.R. Elliott, M.E. Luggen, J.F. Fries, M. Ward, Hydroxychloroquine and risk of diabetes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA 298, 187–193 (2007)

T.S. Sharma, M.C. Wasko, X. Tang, D. Vedamurthy, X. Yan, J. Cote, A. Bili, Hydroxychloroquine use is associated with decreased incident cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 4, 5 (2016)

M.A. Gonzalez-Gay, C. Gonzalez-Juanatey, T.R. Vazquez-Rodriguez et al., Insulin resistance in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of the anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1193, 153–159 (2010)

J. Channual, J.J. Wu, F.J. Dann, Effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade on metabolic syndrome components in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and additional lessons learned from rheumatoid arthritis. Dermatol. Ther. 22, 61–73 (2009)

E. Parmentier-Decrucq, A. Duhamel, O. Ernst et al., Effects of infliximab therapy on abdominal fat and metabolic profile in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 15, 1476–1484 (2009)

F. Ofei, S. Hurel, J. Newkirk, M. Sopwith, R. Taylor, Effects of an engineered human anti-TNF-alpha antibody (CDP571) on insulin sensitivity and glycemic control in patients with NIDDM. Diabetes 45, 881–885 (1996)

H. Dominguez, H. Storgaard, C. Rask-Madsen et al., Metabolic and vascular effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockade with etanercept in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. J. Vasc. Res. 42, 517–525 (2005)

N. Esser, N. Paquot, A.J. Scheen, Anti-inflammatory agents to treat or prevent type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 24, 283–307 (2015)

Q. Javed, I. Murtaza, Therapeutic potential of tumour necrosis factor-alpha antagonists in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart Lung Circ. 22, 323–327 (2013)

J. Zhang, F. Xie, H. Yun, et al, Comparative effects of biologics on cardiovascular risk among older patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. (2016 Jan 20). doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207870. [Epub ahead of print]

S.E. Shoelson, J. Lee, A.B. Goldfine, Inflammation and insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 116, 1793–1801 (2006)

M.J. Yin, Y. Yamamoto, R.B. Gaynor, The anti-inflammatory agents aspirin and salicylate inhibit the activity of I(kappa)B kinase-beta. Nature 396, 77–80 (1998)

T.D. Gilmore, Introduction to NF-kappaB: players, pathways, perspectives. Oncogene 25, 6680–6684 (2006)

A.B. Goldfine, V. Fonseca, K.A. Jablonski, L. Pyle, M.A. Staten, S.E. Shoelson, TINSAL-T2D (TargetingInflammation Using Salsalate in Type 2 Diabetes) Study Team. The effects of salsalate on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 152, 346–357 (2010)

A.B. Goldfine, V. Fonseca, K.A. Jablonski, Y.D. Chen, L. Tipton, M.A. Staten, S.E. Shoelson, Targeting inflammation using salsalate in type 2 diabetes study team. Salicylate (salsalate) in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 159, 1–12 (2013)

A.B. Goldfine, J.S. Buck, C. Desouza et al., Targeting inflammation using salsalate in patients with type 2 diabetes: effects on flow-mediated dilation (TINSAL-FMD). Diabetes Care 36, 4132–4139 (2013)

K. Maedler, P. Sergeev, F. Ris et al., Glucose-induced beta cell production of IL-1beta contributes to glucotoxicity in human pancreatic islets. J. Clin. Investig. 110, 851–860 (2002)

C.M. Larsen, M. Faulenbach, A. Vaag, A. Vølund, J.A. Ehses, B. Seifert, T. Mandrup-Poulsen, M.Y. Donath, Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 1517–1526 (2007)

C. Herder, E. Dalmas, M. Böni-Schnetzler, M.Y. Donath, The IL-1 pathway in type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular complications. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 26, 551–563 (2015)

H.J. Lachmann, I. Kone-Paut, J.B. Kuemmerle-Deschner, K.S. Leslie, E. Hachulla, P. Quartier, X. Gitton, A. Widmer, N. Patel, P.N. Hawkins, Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 2416–2425 (2009)

P.M. Ridker, C.P. Howard, V. Walter, on behalf of the CANTOS Pilot Investigative Group et al., Effects of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on hemoglobin A1c, lipids, C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and fibrinogen. A phase IIb randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation 126, 2739–2748 (2012)

C. Cavelti-Weder, A. Babians-Brunner, C. Keller, M.A. Stahel, M. Kurz-Levin, H. Zayed, A.M. Solinger, T. Mandrup-Poulsen, C.A. Dinarello, M.Y. Donath, Effects of gevokizumab on glycemia and inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 35, 1654–1662 (2012)

J. Sloan-Lancaster, E. Abu-Raddad, J. Polzer, J.W. Miller, J.C. Scherer, A. De Gaetano, J.K. Berg, W.H. Landschulz, Double-blind, randomized study evaluating the glycemic and anti-inflammatory effects of subcutaneous LY2189102, a neutralizing IL-1β antibody, in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 36, 2239–2246 (2013)

N.A. Di Prospero, E. Artis, P. Andrade-Gordon, D.L. Johnson, N. Vaccaro, L. Xi, P. Rothenberg, CCR2 antagonism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 16, 1055–1064 (2014)

S. Kaptoge, E. Di Angelantonio, G. Lowe, M.B. Pepys, S.G. Thompson, R. Collins, J. Danesh, C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet 375, 132–140 (2010)

P.M. Ridker, T. Thuren, A. Zalewski, P. Libby, Interleukin-1β inhibition and the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events: rationale and design of the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS). Am. Heart J. 162, 597–605 (2011)

P.M. Ridker, Testing the inflammatory hypothesis of atherothrombosis: scientific rationale for the cardiovascular inflammation reduction trial (CIRT). J. Thromb. Haemost. 7(Suppl 1), 332–339 (2009)

P.M. Ridker, T.F. Lüscher, Anti-inflammatory therapies for cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 35, 1782–1791 (2014)

M.L. O’Donoghue, R. Glaser, M.A. Cavender, LATITUDE-TIMI 60 Investigators et al., Effect of losmapimod on cardiovascular outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 315, 1591–1599 (2016)

L.K. Newby, M.S. Marber, C. Melloni et al., SOLSTICE investigators. Losmapimod, a novel p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor, in non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet 384, 1187–1195 (2014)

M.Y. Donath, Multiple benefits of targeting inflammation in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 59, 679–682 (2016)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

D. G. and K. E. received speaker fees from Lilly, SANOFI, and NOVARTIS.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maiorino, M.I., Bellastella, G., Giugliano, D. et al. Cooling down inflammation in type 2 diabetes: how strong is the evidence for cardiometabolic benefit?. Endocrine 55, 360–365 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-016-0993-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-016-0993-7