Abstract

This case report describes a 31-year-old man with 10 years of cocaine and cannabis dependence who developed reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (rTC), a rare variant of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. He presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with severe left temporal headache and vomiting which began whilst smoking cannabis and several hours after smoking methamphetamine and using cocaine via insufflation. Computed tomography and angiography of the brain was normal, and the headache resolved with analgesia. Urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, cocaine, opiates (attributed to morphine administered in ED) and amphetamines. Three hours later he had a seizure and within 10 min developed cardiogenic shock with antero-inferior ST segment depression on electrocardiogram and troponin-T rise to 126 ng/L. Coronary angiography demonstrated normal coronary arteries. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated severely impaired left ventricular (LV) systolic function with ejection fraction 15–20% and hypokinesis sparing the apex. Thyrotoxicosis, nutritional, vasculitic, autoimmune and viral screens were negative. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated severe LV functional impairment with dilated and hypocontractile basal segments, and T2 hyperintensity consistent with myocardial oedema and rTC. He received supportive management. Proposed mechanisms of rTC include catecholamine cardiotoxicity and coronary artery vasospasm. In this case, multiple insults including severe headache, cannabis hyperemesis and cocaine and methamphetamine-induced serotonin toxicity culminated in a drug-induced seizure which led to catecholamine cardiotoxicity resulting in rTC. Clinicians should be cognizant of stress cardiomyopathy as a differential diagnosis in patients with substance use disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reverse (also described as inverted or basal) Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (rTC) is rare and accounts for 2.2% of all Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TC), an acute reversible heart failure syndrome also described as stress cardiomyopathy [1, 2]. TC and its variants involve an acute coronary syndrome-like presentation in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease, typically triggered by catecholamine-induced cardiotoxicity [3]. rTC is an anatomical variant of TC characterised by basal hypokinesis and apical hyperkinesis, and typically presents at a younger age and with less severe left ventricular (LV) impairment [3]. Several drug-induced precipitants of rTC have been described [3].

Case Details

A 31-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department (ED) at 3:00 am with three hours of severe left temporal headache and vomiting which began whilst smoking cannabis, several hours after smoking methamphetamine and using cocaine via nasal insufflation. He denied recent shortness of breath, orthopnoea, chest pain or limb swelling. Two days earlier he was able to perform intense physical exercise without limitation.

He had been diagnosed with depression three months earlier and commenced on escitalopram 10 mg daily. Over the past 2 years he had presented to hospital multiple times with cannabis hyperemesis and took metoclopramide, hyoscine butylbromide and diazepam pro re nata for vomiting and abdominal cramps.

He had a long-standing history of polysubstance use from the age of 18, including cocaine for 10 years (1–1.5 g via nasal insufflation twice weekly), cannabis for 3 years (2 mg oil per week smoked via vaporiser daily), gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) for 4 years (3 mL oral weekly, previously daily), prescribed and illicit benzodiazepines 5–15 mg oral daily diazepam equivalents, four cigarettes daily and once weekly alcohol binges of ten standard drinks. The methamphetamine use prior to his presentation (three puffs) was the first use.

On initial examination, he had a body mass index of 15.4 kg/m2, heart rate was 91 beats per minute (bpm), blood pressure (BP) 163/107 mmHg, respiratory rate 24 breaths/min, temperature 36.5 °C, oxygen saturations 100% and Glasgow Coma Scale 15 (Fig. 1). He was agitated and diaphoretic which improved following analgesia. Heart sounds were dual with no murmurs and his chest was clear to auscultation. Abdomen was soft and non-tender. There was no peripheral oedema. He was clinically dehydrated. There was lower limb hyperreflexia with sustained ankle clonus. Pupils were 4 mm bilaterally and reactive to light. There were no other neurological findings. He was in urinary retention with 900 ml on bladder scan requiring indwelling catheter insertion. Urinalysis demonstrated protein + , ketones + and trace of non-haemolysed blood.

Initial treatment included 15 mg intravenous (IV) morphine over an hour leading to headache resolution, as well as 10 mg oral metoclopramide, 1 g oral paracetamol and 1 L IV 0.9% sodium chloride. Routine pathology showed normal renal function, white cell count and C-reactive protein. Liver function was normal aside from an isolated elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) of 68 U/L [reference interval (RI) 5–50]. Albumin and protein were slightly elevated at 49 g/L and 83 g/L (RI 33–48 and 60–80, respectively), as was haemoglobin (176 g/L), which all normalised with IV fluids. Urine drug screen was positive for benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, cocaine and metabolites, amphetamine-type substances and opiates (attributed to morphine administered in ED) and negative for methadone. Computed tomography of the brain (CTB) and angiography (CTA) from the aortic arch to Circle of Willis excluded intracranial haemorrhage, ischaemia and dissection.

Two and a half hours post presentation he became tachycardic (150 bpm) with tonic extension of all four limbs and deviation of eyes superiorly then left. This resolved following administration of 5 mg IV midazolam and 1 mg IV benztropine. Venous blood gas showed a mixed respiratory and metabolic acidosis with pH 6.99, pCO2 73 mmHg, HCO3 17 mmol/L and lactate 16.0 mmol/L. This was considered to be due to a drug-induced seizure or less likely, a dystonic reaction to metoclopramide. There were no further episodes.

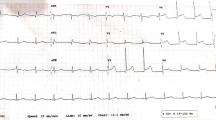

Within 10 min, he developed cardiogenic shock and hypothermia (33.9 °C). He became hypotensive (systolic BP 54 mmHg) and was cold peripherally. Heart rate was 82 bpm and oxygen saturation was maintained at 99% without supplemental oxygen. There was vasospasm on attempt to insert a radial arterial catheter. Troponin-T was elevated at 126 ng/L (RI ≤ 14 ng/L) and electrocardiogram demonstrated antero-inferior ST segment depression and QTc 412 ms (Fig. 2). Following aspirin and ticagrelor loading, an emergent coronary angiogram via the femoral artery demonstrated normal coronary arteries and no vasospasm was observed. Antiplatelets were ceased. A provisional diagnosis of cardiogenic shock due to drug-induced cardiomyopathy and coronary artery vasospasm was made. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) on day one demonstrated severe impairment of LV systolic function with an ejection fraction (EF) of 15–20%, normal wall thickness and hypokinesis of the entire septum, anterior wall, postero-lateral wall and inferior wall, with contractility best preserved at the apex (Table 1). There was mild mitral and tricuspid regurgitation. He was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). He then developed overt pulmonary oedema with hypoxaemia, shortness of breath and consistent findings on chest radiograph. This improved with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and a furosemide infusion. Troponin peaked at 1126 ng/L at 12:10 pm (6.5 h post seizure). NT-pro-BNP was elevated to 401 ng/L (RI ≤ 125). Dobutamine infusion was commenced and levosimendan infusion added on day 2. Day 5 TTE demonstrated some improvement in LV systolic function with EF 37%, diffuse hypokinesis with regional variation and contractility best preserved at the apex and apical third segments. Dobutamine and levosimendan were discontinued on day 6 due to improvement in haemodynamics.

Initially in ICU he was agitated, confused and impulsive, requiring parenteral sedation with dexmedetomidine, midazolam and droperidol. Diazepam was continued regularly.

Thyrotoxicosis, vasculitic, nutritional, autoimmune and viral screens were negative. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) showed mildly dilated LV with severe impairment of function with dilated and hypocontractile basal segments which were hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging consistent with myocardial oedema (Fig. 3). There was no late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) of the myocardium to suggest infiltration or scar. These findings were consistent with rTC.

Cardiac magnetic resonance demonstrating reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. a Four chamber cine end diastolic image shows normal chamber size and wall thickness. b Four chamber cine end systolic image shows hypokinetic basal-mid LV with preserved apical contraction. c T2-weighted image shows hyperintense myocardial signal in the basal-mid LV consistent with oedema. d No late gadolinium enhancement to suggest infiltration or scar

He was commenced on candesartan, an angiotensin II receptor blocker and bisoprolol, a cardioselective beta-1 blocker and discharged to a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility after 2 weeks. At one month he was asymptomatic, had a completely normal TTE including LVEF 70% and candesartan and bisoprolol were ceased. He had returned to work and exercise by 6 weeks.

Discussion

In this case, a number of factors likely led to a catecholamine surge including severe headache, cannabis hyperemesis, cocaine and methamphetamine-induced serotonin toxicity and a drug-induced seizure. Acute catecholamine cardiotoxicity likely resulted in myocardial stunning which led to rTC [1]. Given the presence of radial artery spasm on attempted arterial catheter insertion, it is possible that acute cocaine-related multivessel coronary artery spasm also played a role in the pathogenesis, although angiographic vasospasm was not observed [1].

This case occurred in a young male adult, which is typical of rTC, as opposed to TC which tends to occur in postmenopausal females [1]. This may be explained by the distribution of cardiac adrenoreceptors which are most concentrated at the base of the heart in younger adults, and the apex in older persons, resulting in increased sensitivity to circulating catecholamines in these regions [4, 5].

All reported cases of rTC have occurred in the setting of emotional or physical stress, compared to TC cases which have no identifiable precipitant in up to 30% [5]. rTC due to prescribed drugs is predominantly due to sympathomimetics, including epinephrine (adrenaline) injections [6,7,8]. Like sympathomimetic drugs, seizures are also associated with an increase in monoamines and have been reported as triggers for both TC [1, 9, 10] and rTC [9].

On review of the literature, we found twelve case reports involving fourteen cases of rTC due to non-prescribed drugs as seen in Table 2 [4, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Thirty six percent (5/14) were female and the median age was 29 years (IQR 23–47 years). The drugs implicated were amphetamines (n = 6), methamphetamine (n = 2), cannabis (n = 1), caffeine and 1,3-dimethylamylamine in an energy drink (n = 1), cocaine (n = 1), cocaine and methamphetamine (n = 1), caffeine and dimethylhexylamine in a weight loss supplement (n = 1) and yohimbine in a supplement for erectile dysfunction (n = 1). LVEF data were available for thirteen patients which was complete (initial and recovery) for nine patients and partially complete for four patients. Median initial LVEF was 36% (IQR 18–44%) and normalisation occurred after a median of 6 days (IQR 3–60 days). Our case involved similar initial LVEF impairment and rapid recovery.

Both cannabis use and cannabis hyperemesis syndrome can lead to a catecholamine surge and hyperadrenergic state and have been associated with TC [22, 23].

Chronic cocaine use can also lead to dilated cardiomyopathy with LV dilatation, hypertrophy and global LV systolic dysfunction, which is potentially reversible with abstinence [24,25,26]. Proposed mechanisms include ischaemia, direct myocardial toxicity, persistent hyperadrenergic state, oxidative stress and individual susceptibility [24]. Cocaine-induced myocarditis, myocardial infarction and arrhythmias have also been described [27].

In our case, pre-existing myocardial damage from chronic cocaine use may have contributed to cardiac dysfunction. However, given the patient had no symptoms of heart failure prior to admission, this is unlikely to have been significant.

Based on the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale (Naranjo Scale), it is possible that cocaine (score of 4), methamphetamine (4) or cannabis (3) were implicated in causing rTC [28]. Based on the Naranjo Scale, it is also possible that any of the drugs given in ED were culprits given their temporal relationship to development of rTC. However, given that they were single and low dose administrations, and not in any drug classes previously reported to be a causative agent, they are considered less likely to be implicated. Additionally, one of the limitations of the Naranjo Scale is that latency of onset is not taken into consideration.

In the present case there was under-recognition of rTC as the underlying pathology until CMRI was performed on day 6. By this stage, the patient had completed a 5-day dobutamine infusion and 4-day levosimendan infusion, with an improvement in LVEF from 15–20 to 37%. The use of inotropes such as dobutamine is not recommended in TC and its variants. Dobutamine can potentially worsen cardiac failure and prognosis due to sympathomimetic activity at the beta-adrenergic receptors and have a dose-dependent paradoxically negative inotropic effect in TC [1, 29, 30]. Further, dobutamine has been implicated in iatrogenic TC when administered during stress echocardiography [31,32,33]. It is possible that dobutamine administration in the present case delayed the cardiac recovery.

Conclusion

This unusual and multifactorial case involved a drug-induced seizure as a precipitant for rTC. Sympathomimetic drugs remain a common cause of this rare variant of TC. The case highlights that clinicians should be cognizant of stress cardiomyopathy as a differential diagnosis in patients with substance use disorders.

References

Lyon, A. R., Bossone, E., Schneider, B., Sechtem, U., Citro, R., Underwood, S. R., Sheppard, M. N., Figtree, G. A., Parodi, G., Akashi, Y. J., Ruschitzka, F., Filippatos, G., Mebazaa, A., & Omerovic, E. (2016). Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: A Position Statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Heart Failure, 18(1), 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.424

Templin, C., Ghadri, J. R., Diekmann, J., Napp, L. C., Bataiosu, D. R., Jaguszewski, M., Cammann, V. L., Sarcon, A., Geyer, V., Neumann, C. A., Seifert, B., Hellermann, J., Schwyzer, M., Eisenhardt, K., Jenewein, J., Franke, J., Katus, H. A., Burgdorf, C., Schunkert, H., … Lüscher, T. F. (2015). Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(10), 929–938. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1406761

Awad, H. H., McNeal, A. R., & Goyal, H. (2018). Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: A comprehensive review. Annals of Translational Medicine, 6(23), 460–460. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2018.11.08

Chehab, O., Ioannou, A., Sawhney, A., Rice, A., & Dubrey, S. (2017). Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and cardiogenic shock associated with methamphetamine consumption. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 53(5), e81–e83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.06.027

Ramaraj, R., & Movahed, M. R. (2010). Reverse or inverted Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (reverse left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome) presents at a younger age compared with the mid or apical variant and is always associated with triggering stress. Congestive Heart Failure, 16(6), 284–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00188.x

Khoueiry, G., Abi Rafeh, N., Azab, B., Markman, E., Waked, A., Abourjaili, G., Shariff, M., & Costantino, T. (2013). Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the setting of anaphylaxis treated with high-dose intravenous epinephrine. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 44(1), 96–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.09.032

Esnault, P., Née, L., Signouret, T., Jaussaud, N., & Kerbaul, F. (2014). Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy after iatrogenic epinephrine injection requiring percutaneous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 61(12), 1093–1097. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-014-0230-x

Belliveau, D., & De, S. (2016). Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy following exogenous epinephrine administration in the early postpartum period. Echocardiography, 33(7), 1089–1091. https://doi.org/10.1111/echo.13219

Chou, J., Beutler, L. R., & Goldschlager, N. (2016). Electrocardiography evolution in a woman presenting with alcohol withdrawal seizures and cocaine use. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(5), 693–695. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0278

Kyi, H. H., Aljariri Alhesan, N., Upadhaya, S., & Al Hadidi, S. (2017). Seizure associated Takotsubo syndrome: A rare combination. Case Reports in Cardiology, 2017, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8458054

Cotinet, P. A., Bizouarn, P., Roux, F., & Rozec, B. (2021). Management of cardiogenic shock by circulatory support during reverse Tako-Tsubo following amphetamine exposure: A report of two cases. Heart and Lung, 50(3), 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.10.007

Keituqwa Yanez, I., Nicolas-Franco, S., & Gracia Olivas, J. A. (2017). Heart failure in a case of inverted Takotsubo cardiomyopathy due to cocaine and methamphetamine abuse treated with levosimendan. Archives of Cardiovascular Imaging, 5(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.5812/acvi.14401

Meera, S., Vallabhaneni, S., & Shirani, J. (2020). Cannabis-induced basal-mid-left ventricular stress cardiomyopathy: A case report. International Journal of Critical Illness and Injury Science, 10(5), 49–52. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJCIIS.IJCIIS_25_20

Albenque, G., Bohbot, Y., Delpierre, Q., & Tribouilloy, C. (2020). Basal Takotsubo syndrome with transient severe mitral regurgitation caused by drug use: A case report. European Heart Journal—Case Reports, 4(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/EHJCR/YTAA028

Fulcher, J., & Wilcox, I. (2013). Basal stress cardiomyopathy induced by exogenous catecholamines in younger adults. International Journal of Cardiology, 168(6), e158–e160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.08.067

Alsidawi, S., Muth, J., & Wilkin, J. (2011). Adderall induced inverted-Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions, 78(6), 910–913. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.23036

Al-Abri, S., Meier, K. H., Colby, J. M., Smollin, C. G., & Benowitz, N. L. (2014). Cardiogenic shock after use of fluoroamphetamine confirmed with serum and urine levels. Clinical Toxicology, 52(10), 1292–1295. https://doi.org/10.3109/15563650.2014.974262

Movahed, M. R., & Mostafizi, K. (2008). Reverse or inverted left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome (reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy) in a young woman in the setting of amphetamine use. Echocardiography, 25(4), 429–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00604.x

Kaoukis, A., Panagopoulou, V., Mojibian, H. R., & Jacoby, D. (2012). Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with the consumption of an energy drink. Circulation, 125, 1584–1585. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.057505

Dai, Z., Fukuda, T., Kinoshita, K., & Komiyama, N. (2020). Inverted Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with the consumption of a weight management supplement. CJC Open, 2(1), 26–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjco.2019.11.002

Rodriguez-Castro, C. E., Saifuddin, F., Porres-Aguilar, M., Said, S., Gough, D., Siddiqui, T., Mukherjee, D., & Abbas, A. (2015). Reverse Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with use of male enhancers. Proceedings (Baylor University Medical Center), 28(1), 78–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2015.11929197

Latif, Z., & Garg, N. (2020). The impact of marijuana on the cardiovascular system: A review of the most common cardiovascular events associated with marijuana use. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(6), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9061925

Singh, A., Saluja, S., Kumar, A., Agrawal, S., Thind, M., Nanda, S., & Shirani, J. (2018). Cardiovascular complications of marijuana and related substances: A review. Cardiology and Therapy, 7(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40119-017-0102-x

Maceira, A. M., Ripoll, C., Cosin-Sales, J., Igual, B., Gavilan, M., Salazar, J., Belloch, V., & Pennell, D. J. (2014). Long term effects of cocaine on the heart assessed by cardiovascular magnetic resonance at 3T. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 16(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-16-26

Cooper, C. J., Said, S., Alkhateeb, H., Rodriguez, E., Trien, R., Ajmal, S., Blandon, P. A., & Hernandez, G. T. (2013). Dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to chronic cocaine abuse: A case report. BMC Research Notes, 6(536), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-6-536

Zacà, V., Lunghetti, S., Ballo, P., Focardi, M., Favilli, R., & Mondillo, S. (2007). Recovery from cardiomyopathy after abstinence from cocaine. Lancet, 369(9572), 1574. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60711-9

Vasica, G., & Tennant, C. C. (2002). Cocaine use and cardiovascular complications. Medical Journal of Australia, 177(5), 260–262. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04761.x

Naranjo, C. A., Busto, U., Sellers, E. M., Sandor, P., Ruiz, I., Roberts, E. A., Janecek, E., Domecq, C., & Greenblatt, D. J. (1981). A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 30(2), 239–245.

Paur, H., Wright, P. T., Sikkel, M. B., Tranter, M. H., Mansfield, C., O’Gara, P., Stuckey, D. J., Nikolaev, V. O., Diakonov, I., Pannell, L., Gong, H., Sun, H., Peters, N. S., Petrou, M., Zheng, Z., Gorelik, J., Lyon, A. R., & Harding, S. E. (2012). High levels of circulating epinephrine trigger apical cardiodepression in a β2-adrenergic receptor/Gi-dependent manner: A new model of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circulation, 126(6), 697–706. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.111591

Abe, Y., Tamura, A., & Kadota, J. (2010). Prolonged cardiogenic shock caused by a high-dose intravenous administration of dopamine in a patient with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Cardiology, 141(1), e1–e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.123

Abraham, J., Mudd, J. O., Kapur, N., Klein, K., Champion, H. C., & Wittstein, I. S. (2009). Stress cardiomyopathy after intravenous administration of catecholamines and beta-receptor agonists. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 53(15), 1320–1325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.020

Arias, A. M., Oberti, P. F., Pizarro, R., Falconi, M. L., Pérez De Arenaza, D., Zeffiro, S., & Cagide, A. M. (2011). Dobutamine-precipitated Takotsubo cardiomyopathy mimicking acute myocardial infarction: A multimodality image approach. Circulation, 124, e312–e315. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008557

Mosley, W. J., Manuchehry, A., McEvoy, C., & Rigolin, V. (2010). Takotsubo cardiomyopathy induced by dobutamine infusion: A new phenomenon or an old disease with a new name. Echocardiography, 27(3), e30–e33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8175.2009.01089.x

Funding

This research did not receive any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EN reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. DMR critically revised the manuscript. NJ conceived the idea to report the case and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version and agree to be accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and do not have any financial disclosures.

Consent for Publication

The patient provided written informed consent for publication.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Y. Robert Li.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nash, E., Roberts, D.M. & Jamshidi, N. Reverse Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Precipitated by Chronic Cocaine and Cannabis Use. Cardiovasc Toxicol 21, 1012–1018 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-021-09692-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-021-09692-9