Abstract

ᅟ

The increase in cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is well known; however, appropriate management of this elevated risk in rheumatology clinics is less clear.

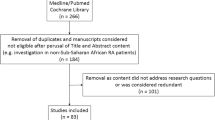

Purpose of Review

By critically reviewing literature published within the past 5 years, we aim to clarify current knowledge and gaps regarding CVD risk management in RA.

Recent Findings

We examine recent guidelines, recommendations, and evidence and discuss three approaches: (1) RA-specific management including treat-to-target and medication management, (2) assessment of comprehensive individual risk, and (3) targeting traditional CVD risk factors (hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, obesity, and physical inactivity) at a population level. Considering that 75% of US RA visits occur in specialty clinics, further research is needed regarding evidence-based strategies to manage and reduce CVD risk in RA.

Summary

This review highlights clinical updates including US cardiology and international professional society guidelines, successful evidence-based population approaches from primary care, and novel opportunities in rheumatology care to reduce CVD risk in RA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) experience elevated risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) including 50–70% higher risk of heart disease than the general population [1, 2]. Still, optimal ways to assess and manage this elevated risk are unknown, and there are few guidelines or evidence-based practices for managing CVD risk in RA. Recent recommendations from the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and a few recent controlled trials offer some guidance and are further discussed. Additionally, updates from US cardiovascular guidelines and evidence-based practices from primary care are highlighted. We aim to critically appraise the recent literature and suggest future directions by examining three strategic approaches to addressing cardiovascular risk: (1) an RA disease-centric approach including treat-to-target and RA medication management, (2) assessment of comprehensive individual risk via risk scores, and (3) management of traditional CVD risk factors using a clinic population-based model. Table 1 provides examples and an overview of these approaches. Given that 75% of US RA visits occur in specialty care [3], rheumatology clinics have a tremendous opportunity to help patients with RA to manage and reduce CVD risk.

RA-Centered

RA Control

One strategy for managing CVD risk in RA is by focusing on RA control. A benefit of this approach is that it leverages disease-specific expertise by rheumatologists. Mechanistically, RA inflammation increases arterial stiffness [4, 5], changes lipid salvage [6,7,8], and destabilizes plaque [9,10,11], among other physiologic changes, predisposing to rupture and infarction (Fig. 1). This makes control of RA inflammation an obvious target to reduce CVD. Both flares and cumulative burden of disease have been associated with increased CVD risk [12•]. Better control of RA activity has recently been associated with fewer cardiovascular events [13•]. Treat-to-target is the new gold standard for achieving RA control which has been shown to improve numerous outcomes [14••] in randomized controlled trials [15•, 17]. “Abrogation of inflammation” by controlling RA, as emphasized in the 2014 treat-to-target update, improves CVD risk given the association between chronic inflammation and CVD [10]. It should be acknowledged, however, that a purely RA-centered approach to CVD risk management may overlook other important modifiable risk factors.

Glucocorticoids

A second consideration with an RA-specific focus on CVD risk is RA medication management, including the use of glucocorticoids. Both dose and duration of glucocorticoid use are associated with increased CVD risk [18•, 19]. In one study, authors reported that a dose threshold of 8 mg prednisone daily was associated with all-cause and CVD mortality [20•]. Another reported a 13% increased risk of myocardial infarction per 5 mg/day dose increase [18•]. The latter cohort study also noted that both current and cumulative steroid dose increased risk of myocardial infarction. A 10-year follow-up of a 2-year randomized trial of low dose prednisolone in RA noted a trend towards reduced survival and increased cerebrovascular disease [19]. Therefore, the updated 2017 EULAR recommendations [21••] on CVD risk management in RA advocate establishing a plan to stop or taper glucocorticoids to the lowest dose as soon as clinically feasible.

RA Treatments

Additional understanding has also emerged regarding the effects of many RA treatments on cardiovascular risk in recent years. Cox inhibitors including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have known CVD risk, with rofecoxib as the most notorious offender [22]. However, a recently published study found moderate doses of celecoxib to be non-inferior to ibuprofen and naproxen for cardiovascular risk [23•] suggesting some risk for all selective and non-selective cox inhibitors. Conversely, antimalarial therapies have been associated with improved cardiovascular profile, potentially via reduction in inflammation, although this association has been debated. One observational study noted a 72% decreased incident CVD risk with hydroxychloroquine use [24]. However, the prospective QUESTRA trial (Quantitative Patient Questionnaires in Standard Monitoring of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis) did not suggest lower CVD event rates with hydroxychloroquine [25]. Methotrexate continues to be studied with regard to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. In 2002, Choi et al. noted a significant survival benefit of methotrexate with a CVD mortality hazard ratio of 0.3 [26]. Most recently, several studies have reported that measures of atherosclerosis, including carotid intima-media thickness, can be reduced with methotrexate and other disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDS) [27,28,29]. The ongoing Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial is even studying the effect of methotrexate on cardiovascular outcomes in a high CVD risk population without RA [30]. Additionally, some suggest that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha blockade improves measures of CVD risk as compared to other DMARDs [31] and a systematic review found that anti-TNF medications may have a positive role in preventing progression of subclinical atherosclerosis [32]. Among newer biologics, while both tocilizumab and tofacitinib increase lipid levels, a post-marketing study on tocilizumab did not show an increase in cardiovascular events [33]. Further randomized controlled trials and long-term follow-up studies addressing CVD risk with RA therapies are warranted.

Comprehensive Individual CVD Risk Assessment

The second approach to managing cardiovascular risk in RA is via comprehensive individual risk assessment. This type of assessment is often accomplished using validated risk assessment tools or prediction scores to calculate individual risk with the goal of tailoring therapy on a per-patient basis. Recognizing that the development of CVD involves a complex interplay of factors including genetic predisposition, medications, disease characteristics, and traditional CV risk factors, assessment of comprehensive individual risk in RA should optimally take into account these factors where current tools may fall short (Fig. 1). One US example of a risk assessment tool is the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD) risk calculator [34], wherein a 10-year calculated CVD mortality risk of >7.5% leads to recommendation of lipid-lowering agents and lifestyle modifications. As discussed above, however, this tool does not take into account RA-specific concerns including disease activity, glucocorticoids, or interactions that raise CVD risk (Fig. 1) or who should calculate and manage risk factors.

Calculating Risk

Calculation of CVD risk can promote early identification and intervention on risk factors, particularly in a high-risk population such as patients with RA. However, risk calculators developed for the general population, including the Framingham risk score and SCORE algorithm, underestimate CVD risk in patients with RA [35, 36], and only the UK-derived QRISK2 [37] includes built-in calculation of RA risk. To address this, new 2017 EULAR task force recommendations advocate using a 1.5 multiplication factor on risk prediction models to estimate CVD risk for all RA patients [21••]. This was in contrast to 2009 recommendations that advocated using this multiplier if certain RA characteristics were present, i.e., disease duration >10 years, seropositivity, and certain extra-articular manifestations [38]. The 2017 update recommends use of this multiplication factor without restriction based upon evidence of increased CVD risk even in patients with early RA or without extra-articular disease [21••]. Additionally, various RA-specific prediction tools have been developed to assess individual CVD risk, including Extended Risk Score-RA (ERS-RA) and A Transatlantic Cardiovascular Risk Calculator for RA (ATACC-RA) [35, 39, 40] with varying success. Moreover, everyday clinical use of all calculated predictors by rheumatologists and primary care physicians has been limited [41]. There remains a need for a validated, user-friendly estimation of CVD risk in patients with RA, with hopes that in the future such calculators could extend to other inflammatory diseases such as psoriatic arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus. Other, simpler, more practical assessment strategies may need to be considered as well.

An often debated aspect of CVD risk management has been whether this care should be the domain of the primary care physician (PCP) or the rheumatologist [42, 43]. EULAR recommendations from 2009 and 2017 emphasize that rheumatologists should be responsible for CVD risk management in RA. However, comprehensive CVD risk calculation and management involves multiple variables including smoking status, diabetes status, gender, age, blood pressure, and lipid values, which might be considered outside routine rheumatology practice. There are benefits to this comprehensive individual risk calculation approach, yet as will be discussed, this is a resource-intensive strategy that may not always be feasible in a busy rheumatology clinic with limited staffing.

Recommendations and Evidence for Risk Assessment

The 2017 EULAR recommendations for CVD risk assessment discuss comprehensive risk assessment, and another international consensus group recently proposed a list of cardiovascular quality indicators for CVD risk evaluation in RA [44•]. EULAR recommends completing comprehensive risk assessments in RA patients “at least once every five years and should be reconsidered following major changes in anti-rheumatic therapy,” and treating high-risk patients or those with established CVD “according to national guidelines.” EULAR and the quality indicators both address goals of reduction of glucocorticoids, assessment of traditional CVD risk factors such as smoking status and cessation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes screening, and emphasize exercise and lifestyle. The quality indicator group even addresses specific frequency of such interventions, for example “physical activity goals should be discussed with their rheumatologist at least once yearly.” The quality indicators also recommend communicating to the primary care physician “that patients with RA have an increased cardiovascular risk.” A recent Canadian chart review noted gaps for many of these indicators, most notably documentation of formal CVD risk assessment, communication to PCP about an elevated blood pressure or increased CVD risk, and body mass index documentation and counseling in less than 10% of encounters [45]. A comprehensive risk assessment program would ideally aim to regularly address each of these risk factors to ensure quality care.

Individual CVD risk factor identification and calculation are suboptimal in many other RA studies [46,47,48], and some have studied RA clinic approaches to identify and manage risk. Primdahl and colleagues studied more than 800 RA patients in the Netherlands, wherein study nurses performed comprehensive screening averaging 30 min per patient to assess CVD risk factors [49••]. They found that 14% of patients without known diabetes had impaired fasting glucose, and 37% had elevated blood pressure. Among 42% already diagnosed with hypertension, only 54% had a systolic blood pressure less than 140 mmHg. These results reiterate the utility of screening RA patients in rheumatology clinics to ensure they are monitored closely for traditional CVD risk factors. This research group also reported that in patients with low RA disease activity, nursing or shared care visits are cost effective [50, 51] and offered more time to discuss individual CVD risk and risk factors. Others have also shown that comprehensively screening individuals with RA for CVD risk is cost effective [52]. Despite these successes, practical considerations for executing comprehensive CVD risk screening in usual care RA clinics remain.

Imaging and Subspecialty Care

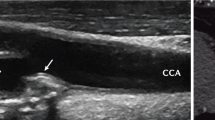

The 2013 AHA/ACC and US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines do not advocate routine first-line use of imaging to assess CVD risk [53]. Yet, some have proposed methods for individual risk assessment in RA patients including imaging such as coronary arterial calcium scoring via cardiac computed tomography (CT) [46] or ultrasound [54]. CT has been shown to correlate with overall magnitude of atherosclerosis and subsequent CVD events in RA [55]. RA patients without known coronary artery disease have higher and more severe plaque burden on CT angiography [56]. One difficulty is that coronary artery calcium assessment only images calcified plaque, which tends to be more stable, whereas vulnerable, unstable plaque may not be visualized. Carotid ultrasound including carotid intima-medial thickness and arterial stiffness is another modality studied to assess CVD burden, and this was predictive of CVD events in a cohort of RA patients [57]. The exact role of imaging in CVD risk assessment in RA patients remains unclear.

Some have proposed referral of high-risk patients to primary care or preventive cardiology and other health systems have developed dedicated cardiology-rheumatology clinics to comprehensively assess at-risk RA patients [58•]. However, in one study of patients with psoriatic arthritis, just 10% of those referred attended a preventive cardiology visit, and ultrasound assessment of carotid plaques and cardiology referral did not change management [59]. Moreover, cardio-rheum clinics are not feasible in all systems, and the above findings suggest that follow-up arranged through primary care or rheumatology clinics might improve impact by ensuring patient attendance and buy-in. Future work could address the utility and cost-effectiveness of such resource-intensive modalities for routine assessment of individual CVD risk in RA.

Targeting Traditional CVD Risk Factors at a Population Level

A third strategy for managing CVD risk in patients with RA is by addressing one or more traditional CVD risk factors at a rheumatology clinic population level. As mentioned, because 75% of RA visits in the USA occur in specialty clinics [3], this could be a prime location to address prevention topics historically attributed to primary care. Population health science supports that such interventions with a wide population reach improve impact, noting that impact is a product of reach times effect [60]. In one study, 80% of RA patients had at least one prevalent cardiovascular risk factor, and rates of traditional risk factors were shown to also be under-diagnosed and poorly controlled in this population [46]. Newly incident CVD risk factors were also higher in RA patients in another study [41]. Understanding that time is valuable and limited, assessment or management of these risk factors may be delegated. Non-MD staff such as nurses or medical assistants may be empowered by the development of staff-led protocol interventions that can take place during rooming or nurse visits as has been tested in primary care [61•].

Hypertension

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has prioritized HTN as a national target for reducing CVD risk at a population level even beyond RA, saying nothing will save more lives than hypertension protocols [62, 63]. Importantly, one study estimated that treating just 11 patients with moderate hypertension (defined as a systolic blood pressure between 140 and 160 mmHg) would prevent one CVD event in the general population [64]. The current Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) guidelines on HTN published in 2014 recommend treatment for a blood pressure >150/90 in adults >60 years or >140/90 in younger adults regardless of comorbidities such as diabetes or RA [65•]. Controversy surrounded these guidelines, and with subsequent evidence of lowered blood pressure across all age groups, the American Society of Hypertension recommends a threshold of 140/90 for all patients [66]. Similar to the general population, in RA HTN is the most prevalent CVD risk factor making it an appealing reversible target. Moreover, in RA, HTN is associated with asymptomatic cardiovascular organ damage on echocardiography, independent of inflammatory activity [67]. One study showed a 29% gap in diagnosis of HTN in RA patients compared to non-RA patients using longitudinal blood pressures [68]. Interestingly, a premier US multispecialty group that used hypertension protocols demonstrated no gap [69]. In that large health maintenance organization, implementation of a system-wide hypertension program with nurse protocols had significantly improved population level blood pressure control rates in RA and non-RA populations [61•]. Similarly, by using electronic medical record alerts and staff protocols, rheumatology clinics can identify and refer patients with high blood pressure to the PCP for management [70, 71]. Given that blood pressure is measured at nearly all RA visits, and HTN is highly prevalent and reversible, it is a prime target for rheumatology clinics.

Tobacco

Tobacco use is a modifiable CVD risk factor of particular importance in RA for reasons beyond risk of cardiopulmonary disease. Smoking is a strong risk factor for RA [72], yet up to one third of patients with RA still smoke [73]. Tobacco use has been linked to progression of RA disease activity [74•] and reduced medication efficacy [75,76,77,78]. In primary care, staff interventions and quit line referrals are effective [79, 81•] and are advocated by USPSTF guidelines [82] and the US Public Health Service [83]. These are also cost-effective interventions; in the USA, quit line services are available free in all 50 states, and Medicare, Medicaid, and most insurance plans will cover tobacco cessation therapies. Specifically, a simple “Ask, Advise, Connect” model was 13 times more effective than passive referral using brochures to get smokers to connect with quit lines [84]. Internationally, Naranjo et al. highlighted the need for more standardized, clinic- or system-wide interventions for tobacco cessation reporting a lack of a protocol in many rheumatology departments, although 65% of rheumatologists self-reported advising their patients to quit smoking “most or all of the time” [84]. In a prospective study by that group, one out of six RA patients quit smoking after a systematic clinical intervention was established [85]. Additionally, a recent study showed equal efficacy of over the counter nicotine replacement therapy and prescription varenicline for successful smoking cessation [86•], potentially simplifying treatment. Given potential gains for both RA control and cardiopulmonary health, tobacco cessation through simple quit line referrals and nicotine replacement counseling could be important rheumatology clinic population interventions.

Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia is another traditional CVD risk factor with interesting implications in RA and CVD risk. A paradoxical lowering of lipid levels is observed in poorly controlled RA despite high ongoing CVD risk due to concurrent inflammation [10]. For this reason, EULAR encourages use of the total cholesterol/high-density lipoprotein (HDL) ratio, which is “a better CVD risk predictor in RA than individual lipid components,” and adds that such measurements are also acceptable in the non-fasting state [21••]. Some authors discuss using low-density lipoprotein (LDL), HDL, or apolipoproteins B or A1 to monitor CVD risk due to chronic inflammation [87]. International recommendations differ with regard to lipid monitoring and management in RA; the United Kingdom and Canada list RA as a risk factor to recommend more frequent testing [37, 88], however the US does not explicitly recommend more frequent testing. EULAR recommendations mention that lipids should ideally be assessed when disease is stable or in remission, but do not comment on specific frequency of testing [21••]. Several authors have noted suboptimal lipid testing in RA [46, 89, 90]. As with assessment of CVD risk, there is also considerable debate on whether lipid management should be the domain of the PCP or the rheumatologist. Whether patients with RA or other inflammatory diseases would benefit from more frequent lipid monitoring especially if their disease is not well-controlled also merits further investigation.

Statins, one of the most important classes of lipid-lowering agents which are also known as HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, demonstrate multiple benefits in RA. Two trials, TRACE (Trial of Atorvastatin for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in RA), which was stopped early due to low event rate, and its predecessor, TARA (Trial of Atorvastatin in RA), showed statistically significant arthritis and lipid-control effects of statins [91, 92]. Another trial reported better articular response in RA patients receiving tofacitinib plus atorvastatin compared to tofacitinib monotherapy [93]. Furthermore, after statin discontinuation, TARA patients experienced increased all-cause and CVD mortality within a month [94] potentially due to loss of anti-lipid and anti-inflammatory effects of statins. Likewise, authors noted a 2% per month frequency of acute MI following statin discontinuation in a population-based RA cohort study [92]. A study reporting that arterial stiffness improved after long-term treatment with rosuvastatin in patients with RA also supports statin use [95]. The 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines simply recommend that clinicians “use clinical judgment in these situations, weighing potential benefits, adverse effects, drug-drug interactions and patient preferences” with regard to initiation of statin therapy in patients with “rheumatologic or inflammatory diseases.” [96•]. Importantly, these new guidelines suggest initiating statins at varying intensities based on the calculated risk profile with lesser emphasis on LDL targets.

Nevertheless, certain RA therapies demand special lipid monitoring. Tocilizumab requires testing at 4 to 8 weeks after initiation and every 6 months thereafter and tofacitinib requires testing 4 to 8 weeks after initiation [97, 98]. There are no evidence-based guidelines for monitoring dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk in patients on chronic glucocorticoids. One study demonstrated that prednisone increased HDL but did not affect LDL or total cholesterol/HDL ratio [99] as supported by EULAR. Conversely, in the TEAR trial and other studies, lipid levels and function improved after initiation of methotrexate or triple therapy via improved disease control [73, 100]. In accordance with major professional society and medication-specific monitoring recommendations, most agree that rheumatologists should execute lipid monitoring in such circumstances [21••].

Diabetes, Obesity, and Physical Inactivity

Finally, we combine diabetes, obesity, and physical activity in the broad category of metabolic conditions to consider in CVD risk management in RA. We and others have noted gaps in screening for diabetes mellitus [42, 49••] and a lack of lifestyle counseling [47, 101]. Reasons for this are likely multifactorial, including lack of time, perhaps lack of knowledge or experience, or a belief that this is managed in primary care [42]. The updated 2017 EULAR recommendations advocate lifestyle counseling, emphasizing the importance of these strategies for overall health. In RA, physical activity slows radiographic disease progression, decreases CVD risk and pain perception, and increases bone mineral density [102]. One study demonstrated significantly improved blood pressure, body mass index, and disease activity and severity after 6 months of an individualized aerobic and resistance high intensity exercise program for RA patients [103]. A second RCT studying resistance training showed restoration of lean mass and function in patients with RA [104], and another demonstrated improved endothelial function, suggesting an improved cardiovascular profile as well [103]. One observational study noted that individuals who were physically active presented with milder RA [105]. Still, in Primdahl’s study, 66% of RA patients did not meet physical activity recommendations [49••]. The EUMUSC.net project, in collaboration with EULAR and the European Union, recommends that providers refer patients with newly diagnosed RA for enrollment in an individualized exercise program [106•]. The CDC recommends four evidence-based programs for physical activity in patients with RA [107•]. Given the numerous benefits of physical activity in RA and potential impact on CVD risk, we suggest rheumatologists address activity and other lifestyle factors at least annually per the quality indicator recommendations [44•].

Limitations in the current literature include a paucity of large randomized controlled studies examining CVD risk management in RA with sufficient longitudinal follow-up to observe changes in CVD event rates. Moreover, some of the best-studied interventions for assessing and modifying risk factors, such as comprehensive nurse or cardiology clinic CVD screening visits [49••, 52], are resource intensive but are deserving of further study. New evidence from beyond rheumatology suggests that varied strategies may be tailored to specific clinic and patient population needs.

Conclusions

Patients with RA, who are at higher CVD risk than their peers, often experience suboptimal management of CVD risk factors. We have discussed three approaches to management of CVD risk in patients with RA: disease-specific, comprehensive individual risk assessment, and rheumatology clinic population-based. From the RA disease-specific standpoint, we recommend treat-to-target care, glucocorticoid reduction, and careful consideration of medications that impact CVD risk. Regarding individual risk, EULAR recommendations suggest comprehensive individual CVD risk assessment with risk calculation at least every 5 years or more frequently with major changes in anti-rheumatic therapy. Regarding traditional risk factors, we encourage initiation of clinic population monitoring strategies aiming for blood pressures of less than 140/90 mmHg, smoking cessation, lipid monitoring, and appropriate statin therapy. Rheumatologists should also counsel patients on lifestyle modifications and physical activity at least annually, and communicate regularly with the PCP regarding CVD risk as recommended by global quality indicators. Given their close relationships with RA patients, who frequently consider rheumatologists their main physicians, rheumatology clinics are well positioned to regularly address modifiable CVD risk factors [21••]. It is imperative to study new strategies to manage CVD risk in RA and other autoimmune conditions given their potential to improve individual and population health.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Lindhardsen J, Ahlehoff O, Gislason GH, Madsen OR, Olesen JB, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. The risk of myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes mellitus: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):929–34.

Avina-Zubieta JA, Thomas J, Sadatsafavi M, Lehman AJ, Lacaille D. Risk of incident cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(9):1524–9.

Schappert SM, Rechtsteiner EA. Ambulatory medical care utilization estimates for 2007. Vital Health Stat 13. 2007;2011(169):1–38.

Avalos I, Chung CP, Oeser A, Gebretsadik T, Shintani A, Kurnik D, et al. Increased augmentation index in rheumatoid arthritis and its relationship to coronary artery atherosclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2007.

Wallberg-Jonsson S, Caidahl K, Klintland N, Nyberg G, Rantapaa-Dahlqvist S. Increased arterial stiffness and indication of endothelial dysfunction in long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008;37(1):1–5.

Charles-Schoeman C, Watanabe J, Lee YY, Furst DE, Amjadi S, Elashoff D, et al. Abnormal function of high-density lipoprotein is associated with poor disease control and an altered protein cargo in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(10):2870–9.

Watanabe J, Charles-Schoeman C, Miao Y, Elashoff D, Lee YY, Katselis G, et al. Proteomic profiling following immunoaffinity capture of high-density lipoprotein: association of acute-phase proteins and complement factors with proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):1828–37.

Charles-Schoeman C, Lee YY, Grijalva V, Amjadi S, FitzGerald J, Ranganath VK, et al. Cholesterol efflux by high density lipoproteins is impaired in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(7):1157–62.

Aubry MC, Maradit-Kremers H, Reinalda MS, Crowson CS, Edwards WD, Gabriel SE. Differences in atherosclerotic coronary heart disease between subjects with and without rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34(5):937–42.

Castaneda S, Nurmohamed MT, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Cardiovascular disease in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30(5):851–69.

Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420(6917):868–74.

Myasoedova E, Chandran A, Ilhan B, Major BT, Michet CJ, Matteson EL, et al. The role of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) flare and cumulative burden of RA severity in the risk of cardiovascular disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015. Population-based cohort study reporting increased CVD risk from both flares and cumulative RA burden.

• Solomon DH, Reed GW, Kremer JM, Curtis JR, Farkouh ME, Harrold LR, et al. Disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of cardiovascular events. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(6):1449–55. Longitudinal US cohort study reporting on the association of RA disease activity and CVD events.

•• Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Burmester GR, Bykerk V, Dougados M, Emery P, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: 2014 update of the recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):3–15. EULAR treat to target recommendations for RA.

• Markusse IM, Akdemir G, Dirven L, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, van Groenendael JH, Han KH, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis after 10 years of tight controlled treatment: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(8):523–31. Randomized controlled trial results of a treat to target study in RA.

Solomon DH, Lee SB, Zak A, Corrigan C, Agosti J, Bitton A, et al. Implementation of treat-to-target in rheumatoid arthritis through a Learning Collaborative: Rationale and design of the TRACTION trial. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(1):81–7.

Axelsen MB, Eshed I, Horslev-Petersen K, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Hetland ML, Moller J, et al. A treat-to-target strategy with methotrexate and intra-articular triamcinolone with or without adalimumab effectively reduces MRI synovitis, osteitis and tenosynovitis and halts structural damage progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the OPERA randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(5):867–75.

• Avina-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, De Vera MA, Choi HK, Sayre EC, Rahman MM, et al. Immediate and past cumulative effects of oral glucocorticoids on the risk of acute myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52(1):68–75. Population-based cohort study in Canada demonstrating correlation between current and cumulative steroid dosing in CVD risk.

Ajeganova S, Svensson B, Hafstrom I. Low-dose prednisolone treatment of early rheumatoid arthritis and late cardiovascular outcome and survival: 10-year follow-up of a 2-year randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4(4):e004259. e-publication.

• del Rincon I, Battafarano DF, Restrepo JF, Erikson JM, Escalante A. Glucocorticoid dose thresholds associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):264–72. Clinic-based cohort study correlating glucocorticoid dose threshold of ≥8mg for increased cardiovascular and all cause mortality.

•• Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, Heslinga M, McInnes IB, Peters MJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017. Updated EULAR CVD risk management recommendations in RA. Highlights include the recommendation to use a risk calculation modifier for all RA patients.

Ray WA, Stein CM, Daugherty JR, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Griffin MR. COX-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of serious coronary heart disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9339):1071–3.

• Nissen SE, Yeomans ND, Solomon DH, Luscher TF, Libby P, Husni ME, et al. Cardiovascular safety of celecoxib, naproxen, or ibuprofen for arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2519–29. Randomized double-blind non-inferiority study in RA and OA patients showing non-inferior risk for CVD events with celecoxib vs. ibuprofen and naproxen.

Sharma TS, Wasko MC, Tang X, Vedamurthy D, Yan X, Cote J, et al. Hydroxychloroquine use is associated with decreased incident cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(1):e002867. e-publication.

Naranjo A, Sokka T, Descalzo MA, Calvo-Alen J, Horslev-Petersen K, Luukkainen RK, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(2):R30. e-publication.

Choi HK, Hernan MA, Seeger JD, Robins JM, Wolfe F. Methotrexate and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1173–7.

Vandhuick T, Allanore Y, Borderie D, Louvel JP, Fardellone P, Dieude P, et al. Early phase clinical and biological markers associated with subclinical atherosclerosis measured at 7 years of evolution in an early inflammatory arthritis cohort. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(1):58–67.

Kim HJ, Kim MJ, Lee CK, Hong YH. Effects of methotrexate on carotid intima-media thickness in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(11):1589–96.

Guin A, Chatterjee Adhikari M, Chakraborty S, Sinhamahapatra P, Ghosh A. Effects of disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs on subclinical atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction which has been detected in early rheumatoid arthritis: 1-year follow-up study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(1):48–54.

Everett BM, Pradhan AD, Solomon DH, Paynter N, Macfadyen J, Zaharris E, et al. Rationale and design of the Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial: a test of the inflammatory hypothesis of atherothrombosis. Am Heart J. 2013;166(2):199–207. e15.

Solomon DH, Curtis JR, Saag KG, Lii J, Chen L, Harrold LR, et al. Cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis: comparing TNF-alpha blockade with nonbiologic DMARDs. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):730. e9- e17.

Tam LS, Kitas GD, Gonzalez-Gay MA. Can suppression of inflammation by anti-TNF prevent progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in inflammatory arthritis? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(6):1108–19.

Curtis JR, Perez-Gutthann S, Suissa S, Napalkov P, Singh N, Thompson L, et al. Tocilizumab in rheumatoid arthritis: a case study of safety evaluations of a large postmarketing data set from multiple data sources. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;44(4):381–8.

Ho KK, Anderson KM, Kannel WB, Grossman W, Levy D. Survival after the onset of congestive heart failure in Framingham Heart Study subjects. Circulation. 1993;88(1):107–15.

Arts EE, Popa C, Den Broeder AA, Semb AG, Toms T, Kitas GD, et al. Performance of four current risk algorithms in predicting cardiovascular events in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(4):668–74.

Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Roger VL, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Usefulness of risk scores to estimate the risk of cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(3):420–4.

Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Vinogradova Y, Robson J, Minhas R, Sheikh A, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1475–82.

Peters MJ, Symmons DP, McCarey D, Dijkmans BA, Nicola P, Kvien TK, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for cardiovascular risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;69(2):325–31.

Arts EE, Popa CD, Den Broeder AA, Donders R, Sandoo A, Toms T, et al. Prediction of cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis: performance of original and adapted SCORE algorithms. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(4):674–80.

Solomon DH, Greenberg J, Curtis JR, Liu M, Farkouh ME, Tsao P, et al. Derivation and internal validation of an expanded cardiovascular risk prediction score for rheumatoid arthritis: a Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America Registry Study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(8):1995–2003.

Jafri K, Bartels CM, Shin D, Gelfand JM, Ogdie A. Incidence and management of cardiovascular risk factors in psoriatic arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(1):51–7.

Bartels CM, Roberts TJ, Hansen KE, Jacobs EA, Gilmore A, Maxcy C, et al. Rheumatologist and primary care management of cardiovascular disease risk in rheumatoid arthritis: patient and provider perspectives. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(4):415–23.

Burgos PI, Alarcon GS. Preventive health services for systemic lupus erythematosus patients: whose job is it? Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(3):124.

• Barber CE, Marshall DA, Alvarez N, Mancini GB, Lacaille D, Keeling S, et al. Development of cardiovascular quality indicators for rheumatoid arthritis: results from an international expert panel using a novel online process. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(9):1548–55. International Delphi study recommending eleven cardiovascular quality indicators for RA.

Barber CE, Esdaile JM, Martin LO, Faris P, Barnabe C, Guo S, et al. Gaps in addressing cardiovascular risk in rheumatoid arthritis: assessing performance using cardiovascular quality indicators. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(11):1965–73.

Chung CP, Giles JT, Petri M, Szklo M, Post W, Blumenthal RS, et al. Prevalence of traditional modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparison with control subjects from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(4):535–44.

Desai SS, Myles JD, Kaplan MJ. Suboptimal cardiovascular risk factor identification and management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cohort analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(6):R270. e-publication.

Panoulas VF, Douglas KM, Milionis HJ, Stavropoulos-Kalinglou A, Nightingale P, Kita MD, et al. Prevalence and associations of hypertension and its control in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(9):1477–82.

•• Primdahl J, Clausen J, Horslev-Petersen K. Results from systematic screening for cardiovascular risk in outpatients with rheumatoid arthritis in accordance with the EULAR recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(11):1771–6. Trial of comprehensive nurse CVD risk screening in RA. Nurse visits for CVD risk assessment identified many new risk factor diagnoses.

Primdahl J, Sorensen J, Horn HC, Petersen R, Horslev-Petersen K. Shared care or nursing consultations as an alternative to rheumatologist follow-up for rheumatoid arthritis outpatients with low disease activity--patient outcomes from a 2-year, randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013.

Sorensen J, Primdahl J, Horn HC, Horslev-Petersen K. Shared care or nurse consultations as an alternative to rheumatologist follow-up for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) outpatients with stable low disease-activity RA: cost-effectiveness based on a 2-year randomized trial. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44(1):13–21.

Kievit W, Maurits JS, Arts EE, van Riel PL, Fransen J, Popa CD. Cardiovascular screening in patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis is cost-effective. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016.

American Heart Association. American Heart Association Position Statement on State Efforts to Mandate Coronary Arterial Calcification and Carotid Intima Media Thickness Screenings Among Asymptomatic Adults. 2012. Available at: http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_467574.pdf. Accessed January 11, 2017.

Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, Lonn E, Kendall CB, Mohler ER, et al. Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21(2):93–111; quiz 89–90.

Budoff MJ, Nasir K, McClelland RL, Detrano R, Wong N, Blumenthal RS, et al. Coronary calcium predicts events better with absolute calcium scores than age-sex-race/ethnicity percentiles: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(4):345–52.

Karpouzas GA, Malpeso J, Choi TY, Li D, Munoz S, Budoff MJ. Prevalence, extent and composition of coronary plaque in patients with rheumatoid arthritis without symptoms or prior diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(10):1797–804.

Ikdahl E, Rollefstad S, Wibetoe G, Olsen IC, Berg IJ, Hisdal J, et al. Predictive value of arterial stiffness and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis for cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(9):1622–30.

• Semb AG, Rollefstad S, van Riel P, Kitas GD, Matteson EL, Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular disease assessment in rheumatoid arthritis: a guide to translating knowledge of cardiovascular risk into clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1284–8. International expert recommendations on CVD risk assessment in RA.

Lucke M, Messner W, Kim ES, Husni ME. The impact of identifying carotid plaque on addressing cardiovascular risk in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:178.

Rose GA. The strategy of preventive medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992.

• Jaffe MG, Lee GA, Young JD, Sidney S, Go AS. Improved blood pressure control associated with a large-scale hypertension program. JAMA. 2013;310(7):699–705. Large pragmatic trial of primary care hypertension protocols that improved population blood pressure control at a large HMO.

CDC. Vital signs: awareness and treatment of uncontrolled hypertension among adults--United States, 2003–2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:703–9.

Frieden TR, King SM, Wright JS. Protocol-based treatment of hypertension: a critical step on the pathway to progress. JAMA. 2014;311(1):21–2.

Ogden LG, He J, Lydick E, Whelton PK. Long-term absolute benefit of lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients according to the JNC VI risk stratification. Hypertension. 2000;35(2):539–43.

• James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–20. Controversial updated hypertension management guidelines from 2014 (JNC 8).

Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, Mann S, Lindholm LH, Kenerson JG, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32(1):3–15.

Midtbo H, Gerdts E, Kvien TK, Olsen IC, Lonnebakken MT, Davidsen ES, et al. The association of hypertension with asymptomatic cardiovascular organ damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Blood Press. 2016;25(5):298–304.

Bartels CM, Johnson H, Voelker K, Thorpe C, McBride P, Jacobs EA, et al. Impact of rheumatoid arthritis on receiving a diagnosis of hypertension among patients with regular primary care. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(9):1281–8.

An J, Cheetham TC, Reynolds K, Alemao E, Kawabata H, Liao KP, et al. Traditional cardiovascular risk factor management in rheumatoid arthritis compared to matched nonrheumatoid arthritis in a US managed care setting. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(5):629–37.

Bartels C, Ramly E, Johnson H, P M, Li Z, Zhao Y, et al. Improving Timely Follow-up After High Blood Pressures in Rheumatology Clinics Using Staff Protocols [Abstract]. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Congress. London, UK: Ann Rheum Dis; 2016. p. 877.

Bartels C, Ramly E, Johnson H, Zhao Y, Lewicki K, Lauver DR. Improved Follow-up of Hypertension in Rheumatology Patients: Results of a Pilot [Abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2015;67(10).

Karlson EW, Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. A retrospective cohort study of cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis in female health professionals. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(5):910–7.

Navarro-Millán I, Charles-Schoeman C, Yang S, Bathon JM, Bridges SL, Chen L, et al. Changes in lipoproteins associated with methotrexate therapy or combination therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the treatment of early rheumatoid arthritis trial. Arthritis Rheumatism. 2013;65(6):1430–8.

• Saevarsdottir S, Rezaei H, Geborek P, Petersson I, Ernestam S, Albertsson K, et al. Current smoking status is a strong predictor of radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the SWEFOT trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(8):1509–14. Secondary analysis comparing smoking and non-smoking RA patients from a randomized non-blinded parallel treatment study.

Abhishek A, Butt S, Gadsby K, Zhang W, Deighton CM. Anti-TNF-alpha agents are less effective for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in current smokers. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16(1):15–8.

Saevarsdottir S, Wedren S, Seddighzadeh M, Bengtsson C, Wesley A, Lindblad S, et al. Patients with early rheumatoid arthritis who smoke are less likely to respond to treatment with methotrexate and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: observations from the Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Swedish Rheumatology Register cohorts. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(1):26–36.

Soderlin MK, Petersson IF, Geborek P. The effect of smoking on response and drug survival in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with their first anti-TNF drug. Scand J Rheumatol. 2012;41(1):1–9.

Hyrich KL, Watson KD, Silman AJ, Symmons DP. Predictors of response to anti-TNF-alpha therapy among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45(12):1558–65.

Boyle R, Solberg L, Fiore M. Use of electronic health records to support smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD008743.

Carson KV, Verbiest ME, Crone MR, Brinn MP, Esterman AJ, Assendelft WJ, et al. Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD000214.

• Vidrine JI, Shete S, Cao Y, Greisinger A, Harmonson P, Sharp B, et al. Ask-Advise-Connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in health care settings. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(6):458–64. Cluster randomized trial that demonstrated than an ask-advise-connect vs an ask-advise-refer strategy resulted in 13 times more tobacco quit line utilization.

Siu AL. Behavioral and pharmacotherapy interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant women: U.S. Preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(8):622–34.

Fiore MC, Jaen CR. A clinical blueprint to accelerate the elimination of tobacco use. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2083–5.

Naranjo A, Khan NA, Cutolo M, Lee SS, Lazovskis J, Laas K, et al. Smoking cessation advice by rheumatologists: results of an international survey. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(10):1825–9.

Naranjo A, Bilbao A, Erausquin C, Ojeda S, Francisco FM, Rua-Figueroa I, et al. Results of a specific smoking cessation program for patients with arthritis in a rheumatology clinic. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(1):93–9.

• Baker TB, Piper ME, Stein JH, Smith SS, Bolt DM, Fraser DL, et al. Effects of nicotine patch vs varenicline vs combination nicotine replacement therapy on smoking cessation at 26 weeks: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(4):371–9. Randomized controlled trial reporting equivalence between nicotine replacement therapy and varenicline for smoking cessation.

Mackey RH, Kuller LH, Moreland LW. Cardiovascular disease risk in patients with rheumatic diseases. Clin Geriatr Med. 2017;33(1):105–17.

Genest J, McPherson R, Frohlich J, Anderson T, Campbell N, Carpentier A, et al. 2009 Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult - 2009 recommendations. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25(10):567–79.

Bartels CM, Kind AJ, Everett C, Mell M, McBride P, Smith M. Low frequency of primary lipid screening among medicare patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(5):1221–30.

Bartels CM, Kind AJ, Thorpe CT, Everett CM, Cook RJ, McBride PE, et al. Lipid testing in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and key cardiovascular-related comorbidities: a medicare analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;42(1):9–16.

Danninger K, Hoppe UC, Pieringer H. Do statins reduce the cardiovascular risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17(6):606–11.

De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, Kopec J, Goycochea-Robles MV, Lacaille D. Statin discontinuation and risk of acute myocardial infarction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(6):1020–4.

McInnes IB, Kim HY, Lee SH, Mandel D, Song YW, Connell CA, et al. Open-label tofacitinib and double-blind atorvastatin in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):124–31.

De Vera MA, Choi H, Abrahamowicz M, Kopec J, Lacaille D. Impact of statin discontinuation on mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(6):809–16.

Ikdahl E, Rollefstad S, Hisdal J, Olsen IC, Pedersen TR, Kvien TK, et al. Sustained improvement of arterial stiffness and blood pressure after long-term rosuvastatin treatment in patients with inflammatory joint diseases: results from the RORA-AS study. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153440. e-publication.

• Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889–934. 2013 ACC/AHA guidelines for adult lipid management.

Micromedex. Tofacitinib: Monitoring. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics; 2017. Available at: www.micromedex.com/pharmaceutical. Accessed January 1, 2017.

Micromedex. Tocilizumab: Monitoring. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics; 2017. Available at: www.micromedex.com/pharmaceutical. Accessed January 1, 2017.

Schroeder LL, Tang X, Wasko MC, Bili A. Glucocorticoid use is associated with increase in HDL and no change in other lipids in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35(6):1059–67.

Charles-Schoeman C, Yin Lee Y, Shahbazian A, Wang X, Elashoff D, Curtis JR, et al. Improvement of high-density lipoprotein function in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate monotherapy or combination therapies in a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(1):46–57.

Bartels CM, Wong J, Johnson H, Voelker K, Smith M. Predictors of cholesterol and lifestyle discussions in rheumatoid arthritis visits: impact of perceived ra control and comparison with other prevention topics [Abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2014. p. S511.

Verhoeven F, Tordi N, Prati C, Demougeot C, Mougin F, Wendling D. Physical activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83(3):265–70.

Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Metsios GS, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJ, Nightingale P, Kitas GD, Koutedakis Y. Individualised aerobic and resistance exercise training improves cardiorespiratory fitness and reduces cardiovascular risk in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(11):1819–25.

Lemmey AB, Marcora SM, Chester K, Wilson S, Casanova F, Maddison PJ. Effects of high-intensity resistance training in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(12):1726–34.

Sandberg ME, Wedren S, Klareskog L, Lundberg IE, Opava CH, Alfredsson L, et al. Patients with regular physical activity before onset of rheumatoid arthritis present with milder disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(8):1541–4.

• Petersson IF, Strombeck B, Andersen L, Cimmino M, Greiff R, Loza E, et al. Development of healthcare quality indicators for rheumatoid arthritis in Europe: the eumusc.net project. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(5):906–8. European expert panel recommendations for RA care quality, which include providing exercise recommendations.

• Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity Programs. 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/interventions/physical-activity.html. Accessed January 11, 2017. CDC recommendation overview for physical activity in arthritis care. This includes five endorsed physical activity programs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Bartels receives peer-reviewed grant funding from Independent Grants for Learning and Change, Pfizer. Aimée Wattiaux and Ann Chodara declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any previously unreported studies with human and animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

All authors confirm that work is original and has not been published elsewhere, including figures and tables.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chodara, A.M., Wattiaux, A. & Bartels, C.M. Managing Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Clinical Updates and Three Strategic Approaches. Curr Rheumatol Rep 19, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-017-0643-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-017-0643-y