Abstract

Purpose of Review

Shared decision-making is a process that involves bidirectional exchange of information between patients and providers to support patients in making individualized, evidence-based decisions about their healthcare. We review the evidence on patient-led decision-making, a form of shared decision-making that maximizes patient autonomy, as a framework for decisions about HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP). We also assess the likelihood that patient-led decision-making occurs for PrEP and describe interventions to facilitate this process.

Recent Findings

Patient-led decision-making is likely to be uncommon for PrEP, in part because healthcare providers lack knowledge and training about PrEP. Few evidence-based interventions exist to facilitate patient-led decision-making for PrEP.

Summary

There is a need for rigorously developed interventions to increase knowledge of PrEP among patients and healthcare providers and support patient-led decision-making for PrEP, which will be increasingly important as the range of available PrEP modalities expands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective at decreasing HIV incidence in populations with high rates of new infections [1•, 2]. However, PrEP uptake has been limited in several key populations in the USA, including Black and Latinx men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender persons, cisgender Black women, and people who inject drugs [3, 4•, 5]. Several barriers to PrEP use exist, including that many individuals who are likely to benefit from using PrEP are unaware of PrEP; have concerns about its effectiveness, safety, or cost; or may not accurately assess their own risk for HIV infection [6,7,8,9]. In addition, many healthcare providers lack the knowledge and skills needed to identify individuals with clinical indications for PrEP and to prescribe PrEP, and they may share patients’ concerns about its use [8, 10••, 11, 12]. Improving patients’ and providers’ knowledge of PrEP and helping them to make informed decisions about its use may overcome these significant barriers to PrEP utilization.

Shared decision-making is a process that involves bidirectional exchange of information between patients and providers to support patients in making individualized, evidence-based decisions about their healthcare [13,14,15]. Nearly two decades ago, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) recognized a need for greater patient autonomy in healthcare and recommended shared decision-making as an optimal practice [16]. Shared decision-making is particularly important for healthcare decisions for which there is not a single “best” option for all patients—known as preference-sensitive decisions—so that patients can make choices that are congruent with their personal values. In practice, shared decision-making occurs on a continuum of decisional responsibility, with decisions made in full by clinicians or by patients at the extremes [17], depending on each patient’s preferred degree of responsibility. Because decisions about sexual healthcare are preference-sensitive and deeply personal [18], patient-led decision-making may represent the ideal approach for PrEP.

In this review, we explore frameworks for patient-led decision-making and how they apply to PrEP, assess the extent to which patient-led decision-making occurs for PrEP, and summarize research about decision-support interventions to promote informed decisions about PrEP. We discuss challenges and opportunities for implementing patient-led decision-making for PrEP and suggest that universal offering of PrEP represents an optimal approach to maximizing patient autonomy in decisions about PrEP use.

What Is Patient-Led Decision-Making?

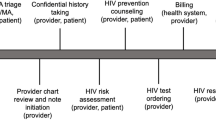

The goal of shared decision-making is to assess each patient’s values and preferences that are pertinent to a specific healthcare decision and then ensure that final decisions are congruent with these values. A systematic review of shared decision-making studies summarized the “essential elements” for providers to engage in shared decision-making with patients [19]. These elements include defining a health-related problem, reviewing benefits and downsides of treatment options, eliciting a patient’s values and preferences, assessing their ability to implement treatment options, providing a clinical recommendation, clarifying patient understanding, and enacting a treatment decision. For PrEP, this might include a discussion about HIV risk and prevention options to decrease risk (including PrEP), discussing patients’ perspectives on different options and the likelihood they could access and adhere to each option, confirming that patients have an accurate understanding of the options, and prescribing PrEP or providing another preferred prevention option.

Patient-led decision-making is a type of shared decision-making that distinguishes itself in two ways. First, it represents an approach that is most appropriate for decisions characterized by equipoise, meaning that one or more options exist that are equally valid, such that an individual’s preferences are the optimal determinants of choice [20]. Second, it is a process in which the patient (and not the provider) has most if not all of the decisional responsibility [17]. In addition to the essential elements for shared decision-making, patient-led decision-making ideally includes eliciting comprehensive details about patients’ health-related behaviors and providing patients with unbiased information about options, so that providers and patients can be confident that true equipoise exists among options for each patient [19]. Additional ideal features of patient-led decision-making include establishing mutual respect with patients and employing a flexible and individualized approach to the decision-making process [19]. For PrEP, this could include eliciting a comprehensive sexual health history, reviewing behavioral and structural determinants of HIV risk (e.g., HIV incidence by zip code), using culturally sensitive and nonjudgmental language [21], and modifying the information exchange and decision-making processes based on each patient’s health literacy and numeracy. For HIV prevention, some individuals may not be aware of their vulnerability to HIV acquisition or might not disclose information about stigmatized behaviors that are associated with HIV exposure, such as injection drug use or sex work, because of the concerns about discrimination from providers. Thus, it is important for clinicians to provide information about PrEP and other preventive options to all patients regardless of the behaviors they disclose, to avoid missed opportunities for patients to learn about and request PrEP. Table 1 summarizes the essential and ideal elements of patient-led decision-making and describes their application to PrEP.

Patient-Led Decision-Making for PrEP: Does It Happen in Clinical Practice?

To understand the need for interventions to facilitate patient-led decisions about PrEP, it is important to know how often this process is already occurring between patients and providers who discuss PrEP. Studies suggest that shared decision-making in general, and patient-led decision-making more specifically, does not commonly occur during clinical encounters for which they would be appropriate. This may be due to lack of provider training and skills in effective communication, time constraints, and a lack of tools to support these processes [22,23,24]. There are limited data on the extent to which shared or patient-led decision-making occur for PrEP. Many providers have limited knowledge about, experience with, and skills related to PrEP [8, 10••, 25, 26, 27 and 28••], suggesting that they are inadequately prepared to engage in shared or patient-led decision-making. Thus, strategies to implement patient-led decision-making for PrEP are needed, with improvements in providers’ knowledge and skills with PrEP as a fundamental priority.

Haynes’s conceptual model of shared decision-making [29] provides a general framework for ways to facilitate patient-led decision-making that can be applied to PrEP. The three major domains of this framework include (1) improving patients’ knowledge of the clinical evidence about treatment options, including data on the risk of harms and benefits for each option; 2) helping patients to clarify their values and preferences around the use of each option; and 3) helping patients to integrate information about their overall clinical state (e.g., comorbidities) and circumstances (e.g., financial constraints) when deciding among options. The model further posits that providers must possess clinical expertise to help patients successfully integrate these domains as part of the decision-making process.

Improving Knowledge of PrEP to Facilitate Patient-Led Decision-Making

Awareness and use of PrEP among patients have increased over the past several years in some key populations, including urban MSM [5]. However, knowledge remains limited in other populations, such as people who inject drugs [4, 8, 30], Black and Latinx populations [31], and heterosexuals in urban centers [31, 32], suggesting that most individuals from these groups will need education about PrEP during discussions with providers.

A large body of evidence from extensive clinical research on PrEP can inform patients’ decisions, if this evidence is provided to patients in an accessible and comprehensible format. Over the past decade, multiple randomized and observational studies have demonstrated that a fixed-dose combination tablet containing two antiretroviral medications, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine (TDF-FTC), is safe and highly effective at preventing HIV acquisition when used with high adherence [2, 33,34,35,36,37]. Most frontline providers will have limited knowledge of these studies because of a lack of experience with HIV and PrEP [10, 28] and may benefit from trainings and tools to help them summarize the research evidence during discussions with their patients. Similarly, because patients vary in their health literacy, numeracy, and knowledge of PrEP, culturally tailored tools that summarize information about PrEP for diverse patient populations are needed to facilitate informed decision-making.

The recent approval of a second daily oral medication for use as PrEP, tenofovir alafenamide with emtricitabine (TAF-FTC), heightens the challenge in providing patients with clinical evidence that is relevant to their individual circumstances. This new option was approved for use as PrEP in October 2019 based on safety and efficacy data from the DISCOVER study, a randomized study that demonstrated that TAF-FTC was non-inferior to TDF-FTC as daily PrEP among MSM and transgender women [38, 39]. Because the DISCOVER study did not enroll other populations, such as cisgender women and transgender men, TAF-FTC was approved as PrEP only for individuals who do not engage in receptive vaginal sex [40]. The DISCOVER study also demonstrated different safety profiles between the two medications, with TAF-FTC being associated with slightly more favorable renal and bone biomarkers but also incrementally more weight gain and dyslipidemia as compared to TDF-FTC. Thus, providers and patients need to understand the complexities of the clinical evidence and prescribing indications for these two PrEP medications for effective and individualized decision-making to occur.

The future availability of additional PrEP options will further increase the need for providers to distill the expanding research evidence on PrEP for their patients. For example, an on-demand PrEP regimen, where patients take a short course of TDF-FTC PrEP shortly before and after the time of sex, is also efficacious for MSM and recommended by the World Health Organization [41] but has not been studied or recommended for use in other populations, such as people who have vaginal sex. Importantly, pharmacokinetic data on TDF in the vagina suggests that this regimen may not provide similar protection [42]. An intravaginal ring that elutes dapivirine, a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, was modestly effective at decreasing HIV incidence among cisgender women in Africa [43, 44]. In July 2020, this formulation received a positive scientific opinion from the European Medicines Agency [45], which will pave the way for World Health Organization guidelines on its use and additional national regulatory reviews, including by the US Food and Drug Administration [46]. A randomized study recently demonstrated that a bimonthly injection of a long-acting formulation of cabotegravir, an HIV integrase inhibitor, was safe and superior in efficacy compared to daily oral TDF-FTC among MSM and transgender women [47]. This regimen will likely be available for prescribing in the near future, pending the completion of a study of cabotegravir among cisgender women in Africa. The availability of multiple formulations of PrEP will bring up new considerations for patient choice, such as preferences around self-administered pills or intravaginal rings versus clinician-administered injections, quarterly clinical visits for oral or topical PrEP versus bimonthly visits for injections, and the discomfort of injections versus the need to ingest pills or insert rings.

Universal Offering of PrEP

An ideal way to ensure that patients are informed about PrEP and have an opportunity to make decisions about its use is for providers to discuss and offer PrEP to all patients as part of routine preventive healthcare [48•]. Universal offering of PrEP would provide each patient with a chance to learn about PrEP, exchange information with providers about benefits and downsides, and decide whether or not to initiate a prescription. Discussing PrEP with all patients, regardless of whether they have disclosed risk factors for HIV acquisition, could also mitigate providers’ implicit bias in PrEP offerings [49, 50] and therefore potentially improve equity in PrEP provision [51]. While a universal approach to offering PrEP is aspirational, there are practical challenges to its implementation, such as needing all primary care providers to be knowledgeable about PrEP, prepared to discuss PrEP within the time available for preventive healthcare, and willing to prescribe or refer. One way to encourage more routine discussion of PrEP would be to draw on providers’ experiences with and strategies for counseling on contraception [52]. Because preventive care for HIV and pregnancy are both components of sexual healthcare and include multiple bio-behavioral options (e.g., oral chemoprophylaxis, barrier protection), providers may feel comfortable adapting communication techniques, including patient-led decision-making, from contraceptive counseling when discussing PrEP [18, 53,54,55,56].

Integrating Patients’ Values, Preferences, and Health Considerations to Individualize PrEP Decisions

Because individual patients are likely to differ in their perspectives and preferences around PrEP options, patient-led decisions will require effective ways for patients to clarify and integrate their values, preferences, and relevant health considerations when deciding about PrEP. Patients’ values and preferences around PrEP use may be influenced by many factors, such as their cultural background and peer norms, concerns about stigma (e.g., being judged for using PrEP), medical and pharmaceutical mistrust, and their sexual partnerships and behaviors [9, 11, 57]. For example, patients may be motivated to use PrEP because of positive experiences among peers, but they may also be cautious about PrEP after encountering misinformation about its safety on trusted social media platforms [58•], resulting in decisional conflict that well-trained providers could help patients to understand and work to resolve. For providers who elicit values from patients, it is of utmost importance that they do so in a nonjudgmental manner, so that patients will feel comfortable providing an unbiased assessment of their values, which in turn can improve the likelihood that their final decision is congruent with their preferences.

Patients and providers will need to collaborate to integrate information about each patient’s personal health status and social circumstances when considering PrEP use. Providers can use their medical expertise to help patients identify pertinent health considerations when choosing among prevention options, such as medical comorbidities (e.g., renal, bone, or metabolic conditions) that could affect the safety of PrEP, drug interactions between PrEP and other medications, and pregnancy or lactational status. Substance use and mental health conditions [59] are common among people who use PrEP and could result in barriers to adherence for some individuals [60, 61], so providers can also support patients by offering examples of strategies to successfully use PrEP in the context of these conditions [62, 63] (and by prescribing or referring patients for treatment). In addition, providers can assist patients in navigating external circumstances that might influence decisions about PrEP use, such as financial, insurance, or social barriers. For example, providers can connect patients to financial assistance programs if patients have difficulties in affording co-payments for PrEP [6], refer patients experiencing homelessness for housing support, in turn potentially mitigating structural vulnerabilities to HIV and facilitating adherence to PrEP, or provide suggestions for how patients can negotiate PrEP use with sexual partners. If patients receive the support they need to access and adhere to PrEP, they may be better positioned to base decisions about PrEP use on their personal preferences instead of external factors, which could improve satisfaction with their decisions.

Decision-Support Interventions for PrEP

For patients to make decisions about PrEP options that resonate with their values, they may benefit from interventions to help with the processing, weighing, and balancing of these options that occur in the final steps of the decision-making process. Moreover, because patients and providers will need to integrate evolving clinical evidence about PrEP options as well as each patient’s personal preferences, health status, and social circumstances—often within the time constraints of brief clinical encounters—there is a need for interventions that can optimize the efficiency of decision-making. An example of this type of intervention would be task-sharing, such as having patients begin the process of information exchange and deliberation with health educators and then concluding with a brief encounter with a provider to enact a decision.

An additional strategy that can potentially improve efficiency and effectiveness is the use of clinical decision aids, which are tools designed to facilitate informed decision-making in healthcare. These tools vary in their format (e.g., online, paper-based), their intended end users (e.g., patients, providers, or both), and their topic area (e.g., treatment or prevention). Clinical decision aids have been developed for many preventive healthcare decisions, including decisions about use of prophylactic medications. Examples include helping individuals to choose among contraception options [64] or whether or not to use statin medications for cardiovascular disease prevention [65]. A comprehensive review found that clinical decision aids tended to help patients to feel more knowledgeable, better informed, and clearer about what matters most to them; they also helped patients have more accurate risk perceptions and a more active role in decision-making [66••], all of which can support patient-led decision-making.

Few evidence-based clinical decision aids have been created for PrEP. An online clinical decision aid to help MSM and their primary care providers decide whether or not to initiate PrEP was developed using the Ottawa Decision Support Framework, a rigorous developmental processes that draws upon concepts from psychology, decision analysis, social support, and economic theory to support patient-centered decisions [67]. This clinical decision aid integrated an individualized HIV risk assessment tool based on prior sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted infections [68] and values clarification exercises about PrEP, such as reflections on how desirable or undesirable it would be to attend follow-up PrEP visits with providers every 3 months. In a pilot study, the decision aid was acceptable to patient and provider participants, improved knowledge about PrEP for these groups, and helped patients feel better prepared to decide whether or not to initiate PrEP [69, 70]. An additional decision aid is being developed using a framework of trauma-informed care to support cisgender women in patient-led decisions about PrEP [71] . Ideally, decision-support tools such as these will be easily modified and updated as new PrEP modalities and new data about the advantages and drawbacks of each modality become available, so that patients and providers can access up-to-date information as they approach decisions about PrEP use. Full-scale studies to test the impact of these decision-support interventions on shared and patient-led decision-making and clinical outcomes for PrEP are needed to inform whether and how to implement these strategies in clinical settings. These studies would ideally measure not only how these tools impact PrEP prescriptions but of equal importance would be how they affect patient experience, including satisfaction with the decision-making process.

While patient-led decision-making may represent the ideal approach for PrEP, providers may have misgivings about honoring patients’ decisions to use PrEP. Some providers have delayed PrEP provision or refused to prescribe PrEP despite direct requests from patients because of their own biases or preconceived notions [72•, 73•], such as inaccurate assumptions that increased condomless sex with PrEP use could increase HIV transmission [12, 45], representing a major threat to patient autonomy. Thus, it will be important for medical opinion leaders and public health authorities to provide clinicians and communities with accurate information on the benefits and risks of PrEP, address misconceptions about PrEP that could deter prescribing behaviors, and disseminate unequivocal guidance that patient-led decision-making represents the best practice for PrEP.

Conclusion

Shared decision-making is the optimal approach for preference-sensitive healthcare decisions, and patient-led decision-making, which maximizes patient autonomy, is well-suited for PrEP. Because many providers and patients lack knowledge of PrEP and have not been prepared to engage in patient-led decision-making about its use, strategies are needed to improve the frequency and quality of this process in clinical settings. Clinical decision aids are being developed for PrEP and merit rigorous testing to assess their impact on decisional processes and clinical outcomes, including patient satisfaction with their decisions. These interventions will need to be adaptable for the diverse populations that could benefit from PrEP, efficient for clinic staff and patients who have limited time during clinical encounters, and flexible to account for new PrEP information and modalities. Universal offering of PrEP during preventive healthcare, which can be achieved if providers adapt successful communication strategies from contraceptive counseling, could increase opportunities to provide PrEP. If patient-led decision-making can be implemented for PrEP, it has the potential to improve PrEP uptake across diverse patient populations, which could help achieve the goal of ending the HIV epidemic in the USA by 2030.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Chou R, Evans C, Hoverman A, Sun C, Dana T, Bougatsos C, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2019;321(22):2214–30 The United States Preventive Services Task Force issued a Grade A recommendation for the use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with emtricitabine as daily oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), indicating strong evidence of net clinical benefit for this regimen. This review summarizes the clinical evidence in support of the Grade A recommendation for PrEP, which can inform decision-support interventions for PrEP.

Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, Blechinger D, Nguyen DP, Follansbee S, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1601–3.

Kanny D, Jeffries WL, Chapin-Bardales J, Denning P, Cha S, Finlayson T, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in HIV preexposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men - 23 urban areas, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(37):801–6.

• McFarland W, Lin J, Santos GM, Arayasirikul S, Raymond HF, Wilson E. Low PrEP Awareness and Use Among People Who Inject Drugs, San Francisco, 2018. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(5):1290–1293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02682-7. This study of people who inject drugs in San Francisco found that only 57% had heard of PrEP, 14% had discussed PrEP with a provider, and 3% had used PrEP in the prior year, highlighting a need for interventions to improve knowledge, patient-provider discussions, and use of PrEP for this key population.

Finlayson T, Cha S, Xia M, Trujillo L, Denson D, Prejean J, et al. Changes in HIV preexposure prophylaxis awareness and use among men who have sex with men - 20 urban areas, 2014 and 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(27):597–603.

Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Dentoni-Lasofsky D, Ellis CG, Silverberg MJ, Slome S, et al. Barriers to preexposure prophylaxis use among individuals with recently acquired HIV infection in Northern California. AIDS Care. 2019;31(5):536–44.

Hill LM, Lightfoot AF, Riggins L, Golin CE. Awareness of and attitudes toward pre-exposure prophylaxis among African American women living in low-income neighborhoods in a Southeastern city. AIDS Care. 2020;25:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1769834.

Qin Y, Price C, Rutledge R, Puglisi L, Madden LM, Meyer JP. Women's decision-making about PrEP for HIV prevention in drug treatment contexts. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2020;19:2325958219900091.

Kimball D, Rivera D, Gonzales M 4th, Blashill AJ. Medical Mistrust and the PrEP Cascade Among Latino Sexual Minority Men. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(12):3456–3461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02916-z.

•• Pleuhs B, Quinn KG, Walsh JL, Petroll AE, John SA. Health care provider barriers to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2020;34(3):111–23 In this systematic review of healthcare provider barriers to PrEP provision in the United States, the authors identified several themes of barriers to PrEP. These themes included providers’ knowledge gaps, discordance in beliefs between HIV specialists and primary care providers on who should prescribe PrEP, interpersonal stigma, and concerns about PrEP costs, patient adherence, and behavioral and health consequences of PrEP use. These barriers represent important targets for interventions to improve providers’ engagement in patient-led decision-making for PrEP.

Goparaju L, Praschan NC, Warren-Jeanpiere L, Experton LS, Young MA, Kassaye S. Stigma, Partners, Providers and Costs: Potential Barriers to PrEP Uptake among US Women. J AIDS Clin Res. 2017;8(9):730. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6113.1000730.

Marcus JL, Katz KA, Krakower DS, Calabrese SK. Risk compensation and clinical decision making - the case of HIV preexposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(6):510–2.

Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7.

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med. 1997;44(5):681–92.

(2001) Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC).

Kon AA. The shared decision-making continuum. JAMA. 2010;304(8):903–4.

Chen M, Lindley A, Kimport K, Dehlendorf C. An in-depth analysis of the use of shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2019;99(3):187–91.

Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–12.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Rollnick S. Dual equipoise shared decision making: definitions for decision and behaviour support interventions. Implement Sci. 2009;4:75.

Marcus JL, Snowden JM. Words matter: putting an end to "unsafe" and "risky" sex. Sex Transm Dis. 2020;47(1):1–3.

Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):291–309.

Legare F, Ratte S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals' perceptions. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(3):526–35.

Blanc X, Collet TH, Auer R, Fischer R, Locatelli I, Iriarte P, et al. Publication trends of shared decision making in 15 high impact medical journals: a full-text review with bibliometric analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2014;14:71.

Blumenthal J, Jain S, Krakower D, Sun X, Young J, Mayer K, et al. Knowledge is power! Increased provider knowledge scores regarding pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are associated with higher rates of PrEP prescription and future intent to prescribe PrEP. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(5):802–10.

Seidman D, Carlson K, Weber S, Witt J, Kelly PJ. United States family planning providers' knowledge of and attitudes towards preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a national survey. Contraception. 2016;93(5):463–9.

Tellalian D, Maznavi K, Bredeek UF, Hardy WD. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection: results of a survey of HIV healthcare providers evaluating their knowledge, attitudes, and prescribing practices. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(10):553–9.

•• Zhang C, McMahon J, Fiscella K, Przybyla S, Braksmajer A, LeBlanc N, et al. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation cascade among health care professionals in the United States: implications from a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2019;33(12):507–27 The authors conducted a systematic review to characterize the PrEP implementation cascade (i.e., awareness, willingness, consultation, and prescription) among health care professionals in the United States. Only two-thirds of professionals were aware or willing to prescribe PrEP, and only about one-third had engaged patients in PrEP consultations, suggesting a need to prepare more providers to engage patients in discussions and decision-making about PrEP.

Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH. Physicians' and patients' choices in evidence based practice. BMJ. 2002;324(7350):1350.

Bazzi AR, Biancarelli DL, Childs E, Drainoni ML, Edeza A, Salhaney P, et al. Limited knowledge and mixed interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(12):529–37.

Misra K, Udeagu CC. Disparities in awareness of HIV postexposure and preexposure prophylaxis among notified partners of HIV-positive individuals, New York City 2015-2017. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76(2):132–40.

Roth AM, Tran NK, Piecara BL, Shinefeld J, Brady KA. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness is low among heterosexual people of color who might benefit from PrEP in Philadelphia. J Prim Care Community Health. 2019;10:2150132719847383.

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99.

Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, Sangkum U, Mock PA, Leethochawalit M, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–90.

Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410.

Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–34.

McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, Dolling DI, Gafos M, Gilson R, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):53–60.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Briefing Information for the August 7, 2019 Meeting of the Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/129607/download.

Mayer KH, Molina JM, Thompson MA, Anderson PL, Mounzer KC, De Wet JJ, et al. Emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide vs emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (DISCOVER): primary results from a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):239–54.

FDA approves second drug to prevent HIV infection as part of ongoing efforts to end the HIV epidemic. FDA news release. October 3, 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-second-drug-prevent-hiv-infection-part-ongoing-efforts-end-hiv-epidemic. .

World Health Organization. What’s the 2+1+1? Event-driven oral pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV for men who have sex with men: update to WHO’s recommendation on oral PrEP [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prep/211/en/.

Cottrell ML, Yang KH, Prince HMA, Sykes C, White N, Malone S, et al. A translational pharmacology approach to predicting outcomes of preexposure prophylaxis against HIV in men and women using tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with or without Emtricitabine. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(1):55–64.

Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, et al. Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2121–32.

Nel A, van Niekerk N, Kapiga S, Bekker L-G, Gama C, Gill K, et al. Safety and efficacy of a dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention in women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2133–43.

European Medicines Agency. Dapivirine vaginal ring 25 mg. July 24, 2020. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/dapivirine-vaginal-ring-25-mg-h-w-2168.

PrEPWatch. Dapivarine vaginal ring. July 24, 2020. Available at: https://www.prepwatch.org/nextgen-prep/dapivirine-vaginal-ring/.

Long-acting injectable cabotegravir is highly effective for the prevention of HIV infection in cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men. HIV Prevention Trials Network news release. May 18, 2020. Available at: https://www.hptn.org/news-and-events/press-releases/long-acting-injectable-cabotegravir-highly-effective-prevention-hiv#:~:text=Overall%2C%20HPTN%20083%20enrolled%204%2C570,%2C%20Vietnam%2C%20and%20South%20Africa.&text=These%20results%20demonstrate%20that%20CAB,cisgender%20men%20and%20transgender%20women.

• Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Integrating HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into routine preventive health care to avoid exacerbating disparities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1883–9 In this commentary, the authors propose routine offering of PrEP as part of preventive health care as a way to reduce inequities in PrEP awareness, access and use.

• Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Krakower DS, Magnus M, Hansen NB, et al. Prevention paradox: medical students are less inclined to prescribe HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for patients in highest need. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(6):e25147 The authors presented medical students with hypothetical scenarios about patients who may benefit from PrEP use and found that students indicted lower prescribing intentions for patients with higher risk of HV acquisition, such as those who intended not to use condoms. These findings suggest that prescribers’ biases about what constitutes appropriate sexual health behaviors could negatively impact patient autonomy in PrEP decisions.

Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, Dovidio JF. The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):226–40.

Chan SS, Chappel AR, Maddox KEJ, Hoover KW, Huang YA, Zhu W, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for preventing acquisition of HIV: a cross-sectional study of patients, prescribers, uptake, and spending in the United States, 2015-2016. PLoS Med. 2020;17(4):e1003072.

Gavin L, Pazol K. Update: providing quality family planning services — recommendations from CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:231–4.

Seidman D, Weber S, Carlson K, Witt J. Family planning providers' role in offering PrEP to women. Contraception. 2018;97(6):467–70.

Seidman D, Weber S. Integrating Preexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus prevention into women's health care in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(1):37–43.

Dehlendorf C, Fitzpatrick J, Steinauer J, Swiader L, Grumbach K, Hall C, et al. Development and field testing of a decision support tool to facilitate shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(7):1374–81.

Dehlendorf C, Grumbach K, Schmittdiel JA, Steinauer J. Shared decision making in contraceptive counseling. Contraception. 2017;95(5):452–5.

Gilkey MB, Marcus JL, Garrell JM, Powell VE, Maloney KM, Krakower DS. Using HIV risk prediction tools to identify candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis: perspectives from patients and primary care providers. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2019;33(8):372–8.

• Nunn AS, Goedel WC, Gomillia CE, Coats CS, Patel RR, Murphy MJ, Chu CT, Chan PA, Mena LA. False information on PrEP in direct-to-consumer advertising. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(7):e455-e456. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30034-5. This study identified false information about PrEP on social media platforms, which could jeopardize effective patient-led decision-making about PrEP. Patients and providers need to be aware that information about PrEP on social media may be inaccurate, and these decision-makers need access to sources of unbiased information about PrEP.

Miltz A, Lampe F, McCormack S, Dunn D, White E, Rodger A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in the PROUD randomised clinical trial of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e031085.

Grov C, Rendina HJ, John SA, Parsons JT. Determining the roles that club drugs, marijuana, and heavy drinking play in PrEP medication adherence among gay and bisexual men: implications for treatment and research. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(5):1277–86.

Hojilla JC, Vlahov D, Glidden DV, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, Hance R, et al. Skating on thin ice: stimulant use and sub-optimal adherence to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(3):e25103.

Hoenigl M, Jain S, Moore D, Collins D, Sun X, Anderson PL, Corado K, Blumenthal JS, Daar ES, Milam J, Dubé MP, Morris S; California Collaborative Treatment Group 595 Team. Substance Use and Adherence to HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis for Men Who Have Sex with Men1. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(12):2292–302. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2412.180400.

Storholm ED, Volk JE, Marcus JL, Silverberg MJ, Satre DD. Risk perception, sexual behaviors, and PrEP adherence among substance-using men who have sex with men: a qualitative study. Prev Sci. 2017;18(6):737–47.

Dehlendorf C, Fitzpatrick J, Fox E, Holt K, Vittinghoff E, Reed R, et al. Cluster randomized trial of a patient-centered contraceptive decision support tool, My Birth Control. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(6):565.e1–e12.

Weymiller AJ, Montori VM, Jones LA, Gafni A, Guyatt GH, Bryant SC, et al. Helping patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus make treatment decisions: statin choice randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(10):1076–82.

•• Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:Cd001431 This Cochrane Database Systematic Review found that people exposed to decision aids before health care decisions tended to feel better informed and clearer about their values, and may have had a more active role in decision making and more accurate risk perceptions. Because the review identified no adverse effects on health outcomes or satisfaction, this review provides strong evidence that decision aids can improve patient-led decision-making in general and thus potentially for PrEP.

O’Connor AM (2006) Ottawa decision Suport framework to address decisional conflict. Ottawa Hosp. Res. Inst. Available at: https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/ODSF.pdf.

Hoenigl M, Weibel N, Mehta SR, Anderson CM, Jenks J, Green N, et al. Development and validation of the San Diego early test score to predict acute and early HIV infection risk in men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(3):468–75.

Krakower D, Powell VE, Maloney K, Wong JB, Wilson IB, Mayer K. Impact of a Personalized Clinical Decision Aid on Informed Decision-Making about HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis among Men who have Sex with Men. 2018. 13th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence. Miami, FL. 2018;8–10.

Powell VE, Mayer K, Maloney KM, Wong JB, Wilson IB, Krakower D. Impact of a Clinical Decision Aid for Prescribing HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis to Men who have Sex with Men on Primary Care Provider Knowledge and Intentions. 2018. 13th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence. Miami, FL. 2018;8–10.

NIH Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tools (RePORT). 5R01MD013565. Offering women PrEP with education, shared decision-making and trauma-informed care: the OPENS Trial. Available at: https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=9892890&icde=51187754&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=1&csb=default&cs=ASC&pball=.

• Skolnik AA, Bokhour BG, Gifford AL, Wilson BM, Van Epps P. Roadblocks to PrEP: What medical records reveal about access to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(3):832–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05475-9. In this qualitative study of clinic notes from the Veterans Health Affairs system, nearly all (94%) of PrEP conversations were initiated by patients, one-third of patients experienced delays receiving PrEP, and 70% of patients faced barriers to accessing PrEP. Barriers to PrEP included provider knowledge gaps about PrEP, confusion or disagreement over clinic purview for PrEP, and stigma associated with patients seeking PrEP. These results indicate a need to improve providers’ skills in communicating with patients about PrEP and prescribing to those patients who decide to initiate PrEP.

• Patel RR, Chan PA, Harrison LC, Mayer KH, Nunn A, Mena LA, et al. Missed opportunities to prescribe HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis by primary care providers in Saint Louis, Missouri. LGBT Health. 2018;5(4):250–6 This study found that nearly half of the patients seeking PrEP at an academic infectious diseases clinic in St. Louis, Missouri had previously asked their primary care providers about PrEP but were not prescribed it. These findings suggest that there are many missed opportunities for patient-led decision-making for PrEP in primary care.

Funding

This publication was made possible with the support from the Harvard University Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program (P30 AI060354), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (K01 AI122853 to JLM), and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Douglas Krakower has conducted research with project support from Gilead Sciences; has received honoraria for authoring or presenting continuing medical education content for Medscape, MED-IQ, and DKBMed; and has received royalties for authoring content for UpToDate, Inc. Julia Marcus has consulted for Kaiser Permanente Northern California on a research grant from Gilead Sciences. Whitney Sewell, Patricia Solleveld, Christine Dehlendorf and Dominika Seidman declare no conflicts.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

All reported studies with human subjects performed by the authors have been previously published and complied with all applicable ethical standards (including the Helsinki declaration and its amendments, institutional/national research committee standards, and international/national/institutional guidelines).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Implementation Science

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sewell, W.C., Solleveld, P., Seidman, D. et al. Patient-Led Decision-Making for HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 18, 48–56 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-020-00535-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-020-00535-w