Abstract

Police officers make significant stress-inducing decisions daily. Given the influence of emotions on police work, we examine the impact of anticipated regret on the decision-making process using a cross-cultural sample. Officers were asked to hypothetically make one of two job-related decisions of varying degrees of severity: shoot a threatening suspect (or not), or issue a speeding ticket (or not). Participants’ avoidant decision-making style, feelings of anticipated regret and predicted actions were analyzed. Results supported the mediated influence of anticipated regret on the relationship between avoidant decision-making style and avoidant decisions. Decision quality was also explored as an outcome which revealed a similar mediating influence of anticipated regret. While we found no significant cross-cultural outcome differences, we did notice differences regarding the use of avoidant decision-making style between the two samples. Implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Decisions made by police officers are often far-reaching. The decision to issue a speeding ticket as an example, once made, affects the civilian and society at large. This places pressure on police officers to consider alternatives carefully when deciding. Arrest or weapon discharge decisions, of course, require even more careful consideration. Of the work performed by police officers, a significant portion involves making decisions and reaching conclusions. In fact, decision-making activities together are rated at an 86% importance level for police officers based on task rankings presented by the Occupational Network (O*NET) (2013). Understanding the factors affecting decision-making among police officers is essential for enhancing decision-making training in police work. Recent research on cognition in police work (e.g., Kassin et al. 2013) also support the value of understanding cognitive factors likely to influence effectiveness within the law enforcement context.

Furthermore, police officers work under very stressful conditions (Daus and Brown 2012; Finn and Tomz 1998; Kop and Euwema 2001). Sources of stress in police work include organizational, operational, criminal justice system actions, personal life, and coping style (Finn and Tomz 1998). Mainly, the demands of human interaction between police officers and the public force them to cope with unique stressors and often of a threatening nature (The American Civil Liberties Union 1992). The coupling of decision-making with stress is a cause for concern.

With the impossibility of controlling the job demands of police work, officers may rely on personal strategies to reduce the influence of job strain or other negative consequences. The influence of these strategies may extend to decision-making processes as individuals struggle with managing decisional stress (Janis and Mann 1977). Furthermore, the effectiveness of these strategies is largely contingent on their appropriateness to situational demands (Kohn 1996). With the high-impact and high-risk situations faced by police officers, the choice of decision strategy should be carefully considered in light of decision-making implications. Once an officer perceives a situation as stressful, a decision is made between either an approach or avoid strategy; each having both cognitive and behavioral implications (Anshel 2000).

With an approach strategy, the officer is most concerned with controlling, improving understanding of the situation, and being resourceful. Conversely, with an avoid strategy the officer is most concerned with creating distance from the stressful situation (Anshel 2000). Both approaches have been suggested as useful in varying situations; however, an approach tendency is generally more adaptive (Anshel 2000). That said, it becomes curious to decipher the mechanism underling decisions not to avoid by those officers with an avoidant tendency. This paper seeks to make sense of the relationship between avoidant decision-making and decisions to avoid, or not, within the context of police work.

This study is expected to contribute to the decision-making literature by providing some evidence explicating the reasons police officers engage in avoidant decision-making. An adequate understanding of the dynamics contributing to the decision-making process in police work is useful to have as this may support communication and change initiatives geared towards reducing the prevalence of poor decision-making in crisis situations. Specifically, we will reinforce the value of the role of regret in decision-making (Ku 2008). The conclusions from these findings will further expand the general theoretical framework on improving decision-making within organizational settings, and especially, within police work.

Avoidant Decision-Making Style

The necessity of understanding the role of individual differences in judgment and decision-making research (Mohammed and Schwall 2009), and police decision-making (Salo and Allwood 2011) specifically, is apparent. The interactionist approach suggests that behavior is a function of both contextual and person-related factors (Endler and Magnusson 1976) which supports the idea of being attentive to trait-like factors influencing decision-making. In situations marked by ambiguity, person-related factors may be increasingly relevant as a source of influence (Mischel 1973). Within the context of police work, it is easy to imagine several ambiguous situations requiring decision-making such as whether a suspect poses a threat to one’s safety or not, or whether to allow some discretion when an anxious driver offers a more-than-reasonable excuse for speeding. In such circumstances, individual differences may play a more significant role in the decision-making process than in situations with less ambiguity.

One direction for exploring individual differences in decision-making focuses on the varying approaches to the process. Decision-making styles are reaction habits in particular decision-making contexts (Scott and Bruce 1995). Five styles have been commonly suggested and utilized in research. They are: intuitive (attention to details and a tendency to rely on feelings); rational (deliberate and systematic); dependent (seeking advice); avoidant (tendency to delay); and spontaneous (immediacy and need for concluding the process quickly) (Scott and Bruce 1995). These decision-making styles are not mutually exclusive. That is, research shows that people may tend to use more than one decision-making style (Thunholm 2003). Therefore, this study assumes decision styles exist on a relative, rather than an absolute, basis and suggests that relationships with other variables may exist. One such category of variables is emotions.

Within the context of managing the demands of decision-making in police work, we are most concerned with the avoidant style. This reasoning stems from the often observed positive relationship between avoidant decision-making and negative stress (Salo & Allwood, 2010; Thunholm 2008). Avoidant decision-making style is also associated with maladaptive cognitive and behavioral tendencies including low self-esteem, compromised regulatory ability, and an inability to act on intentions (Thunholm 2003). This tendency toward avoidance in decision-making conceptually resembles an avoidant approach towards stress management which potentially has negative well-being and performance implications for police work.

Decision Avoidance

Decision avoidance occurs as an individual evades making a decision by delaying or choosing options perceived as non-decisions, i.e. no action or no change (Anderson 2003). One preference of decision avoidance, the status quo bias, results in no change and is based on the assumption that people prefer having things remain as they are (Anderson 2003). Therefore, a police officer’s decision not to arrest the breadwinner of a household may be cognitively impacted by his/her desire not to disturb the stability of this family. Similarly, an officer may decide not to issue a speeding ticket as this may disrupt the current state of affairs. We suggest that avoidant decision-making style will be related to avoidant decisions within the context of police work.

Hypothesis 1

Decision-making avoidant style will be positively related to avoidant behavior such that police officers with an avoidant decision-making style will be more likely to avoid acting.

Further, we apply a non-consequentialist approach to understanding police decisions to avoid by incorporating the contribution of emotions in the decision-making process where emotions influence choice by having mediating control (Anderson 2005). Recent research within the forensic science point to the significance of emotional factors working in conjunction with cognitive processes to influence decision-making (Dror et al. 2005). In this study, we focus on the influence of anticipated regret.

Anticipated regret

Two general categories of emotions have been found to influence the decision-making process: actual and anticipated emotions (Ng and Wong 2008). On one hand, the influences of positive and negative affect experienced during decision-making have been considered for their impact on decision quality. The ‘sadder-but-wiser hypothesis’ proposed by Alloy and Abramson (1979) is one example of this which suggests that the presence of negative emotions improves the quality of decisions. The general explanation behind the sadder-but-wiser hypothesis suggests that the experience of negative affect allows decision-making to occur with more consideration of factors outside the individual’s control (Golin et al. 1977), as well as allowing less impact of self-protective biases (Taylor and Brown 1988).

On the other hand, emotions expected or anticipated by a particular decision have been proposed to influence choices made based on the individual’s desire either to prevent or experience the emotion. The role of emotions in the decision-making process may therefore act as a prohibitive force in the course of action (Anderson 2003; Fredin 2008). For example, regret—a negative emotion which is experienced on realizing or suspecting an outcome would have been better under an alternative choice (Zeelenberg 1999)—is often avoided. Regret theorists have argued that negative emotions are avoided and, as a result, choices are made in light of the intention to facilitate this avoidance (Dijk and Van Harreveld 2008). Extending this to law enforcement, a police officer, aware of the possible negative consequences of the inappropriate use of force, may consider this in making his/her decision so as to avoid these consequences. Anticipated negative emotion in the decision-making process may therefore be regulated through the tendency to avoid.

Hypothesis 2

Decision-making avoidant style will be positively related with anticipated regret, such that police officers with a stronger avoidant style will experience more anticipated regret when making a decision.

Regret is experienced as a result of a discrepancy between expectations and outcomes with some element of personal responsibility; further, sources of regret may include the things we do: ‘action regret,’ or our failure to act: ‘inaction regret’(Dijk and Van Harreveld 2008). Being a negative emotion, it is then safe to assume that the experience of regret would be preferred to be avoided. That being the case, regret serves to enhance the decision-making process as individuals may seek to avoid choosing an option that would induce the experience of negative feelings. In order for this emotion to be experienced, the thought process of an individual has a critical role.

To highlight the thinking which takes place prior to feelings of regret, Dijk and Van Harreveld (2008) contrast regret with disappointment. Disappointment is also the result of a disparity between expectation and reality, or counterfactual thinking. However, disappointment is experienced when this counterfactual thinking occurs under an alternative outcome outside an individual’s control. Regret, they argue, occurs when counterfactual thinking occurs had one chosen differently. The clear implication of this difference is that regret involves more of an element of personal responsibility. Therefore, we may feel disappointment should we make an investment and experience a loss of profit versus a gain. Conversely, we feel regret when another opportunity is presented which we decided against making an investment in.

Anderson (2005) also argues that decision-makers are more likely to anticipate regret in situations where they feel a high degree of social responsibility. He suggests this occurs due to regret involving a self-blame component. Using Anderson’s (2005) logic, decisions of a law enforcement officer to arrest a suspect, may therefore cause feelings of regret given the high degree of social responsibility inherent to their job role. We therefore suggest that anticipated regret will be significantly related to avoidant behavior in police work.

Hypothesis 3

Anticipated regret will be positively associated with decisions of avoidant behavior such that when police officers anticipate regret, they will choose to avoid action more than when less regret is anticipated.

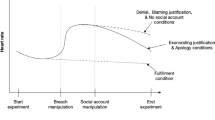

Additionally, an avoidant tendency toward decision-making in police work occurs as a result of anticipated regret. We suggest that the ambiguity associated with some decision-making tasks required by police officers results in more reliance on individual differences as context cues are less apparent (Mischel 1973). Police officers with an avoidant tendency and faced with difficult decision tasks may therefore rely on their personal inclination which may be further supported by expectations that an approach tendency may result in feelings of regret (see Fig. 1).

Hypothesis 4

Anticipated regret will mediate the relationship between decision-making avoidant style and decision avoidant behavior.

With our interest in examining the effect of an individual difference variable on the decision-making process, we decided to incorporate a situational consideration. The person-situation interactional model to understanding human behavior has long been of interest in psychology (Endler and Magnusson 1976). Cultural differences seem a natural contextual variable to examine when possible. Therefore, we examined our hypotheses using data from two countries: Jamaica and the United States. The nature of police work in these countries was expected to vary as a result of cultural and social differences. Hofstede’s (1984) cultural value taxonomy is useful to bear in mind as we examine differences between Jamaica and the United States. The two countries differ primarily on the individualism/collectivism and uncertainty avoidance dimensions which may provide some ideas for speculations about our findings. The United States scores higher on both individualism dimension (95 vs. 39) and uncertainty avoidance (46 vs. 13). This means that in the United States, employees are often more self-sufficient and have a higher preference for avoiding uncertainty in comparison to Jamaica. Therefore, hypothetically, it may be the case that officers in the U.S. sample may expect more regret when faced with ambiguous situations as their preference is for more certainty. To our knowledge, no previous work had examined these differences.

Research Question 1

Does country (Jamaica vs. the United States) influence the proposed mediated relationship between avoidant decision-making and avoidant behavior?

Additionally, since we had two decisions situations of greatly variant degrees of severity, we decided to examine the implications our proposed mediating relationship would have on the quality of decisions made across situations. Our research largely focuses on whether the decision made was one of avoidance or not but it is also relevant to explore these decisions on the basis of their effectiveness.

Research Question 2

Does the type of decision (shoot vs. ticket) affect the quality of decisions as explained by anticipated regret?

Method

Participants

Law enforcement officers (N = 120) were recruited from several Midwestern, U.S. cities’ police departments and one police department in Kingston, Jamaica. Of the U.S. sample (n = 71), 27 officers were employed at three police departments within suburban communities, while 44 officers worked across police departments within more inner-city settings. The remaining 49 officers were from the participating Jamaican police department located in urban Jamaica. Eighty-four percent of the sample was male, and 16% female. Regarding race, 60% of the sample included Caucasians, 39% were Black/African American and 1% Hispanic. Participants had an average of 11 years’ experience, and average age (M) was 36 (SD = 8.21). The average number of hours worked per week was 43 (SD = 11.38). See Table 1 for descriptives of full sample.

Procedure

Contact was made with responsible parties from several police departments in a Midwestern city in the United States, and one police department in Kingston, Jamaica. Participation was requested and officers were asked to volunteer with guarantee given of anonymity and confidentiality. Officers were also assured that the responses would in no way affect their jobs.

Participants were asked to complete questionnaires. First, the decision-making style of the officers was assessed using the General Decision-Making Style Inventory (GDMS; Scott and Bruce 1995). This measures five decision-making styles including rational, dependent, avoidant, intuition and spontaneous. Participants were also asked to complete the demographics measure.

Second, officers were presented with one of two decision-making scenarios (between Ss design) and asked to indicate how much anticipated regret they would expect to feel given the situation, and later to make a decision based on the information presented. The two scenarios were of greatly varying severity: one requiring a decision to use force/not use force versus ticket/not issue ticket. The scenario requiring a decision using force was in the form of a domestic violence altercation with options based on the continuum of force (Terrill 2001). The final and most severe option was to shoot. In order to disguise the research focus on anticipated regret, participants were also asked to rate the extent to which they anticipated feelings of additional emotions such as pride, being at peace, embarrassment and a general question about the impact the decision would have on their mood. For this assessment, each decision-making style was represented with a statement of an action. For example, ‘thinking about what other officers have done in the past’ was used to represent a dependent decision-making style.

Measures

Demographic measure

Participants completed a questionnaire to assess the demographics of the sample. This measure included age, race, gender, job role, hours worked per week and years of experience within law enforcement.

Decision-making style

The General Decision-Making Style Inventory (GDMS; Scott and Bruce 1995) is a 24-item questionnaire which measures individual decision-making styles using a 5-point rating scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The GDMS was used to assess avoidant decision-making style (Gambetti et al. 2008). The subscale alpha for the GDMS in the current study was .68. Sample items (Scott and Bruce 1995, pg. 825-826) include, “I avoid making important decisions until the pressure is on”.

Anticipated regret

Anticipated regret was measured with a single-item measure (“To what extent do you feel you might regret this decision?”) using a 5-point Likert-type scale (Anchors: 1, not at all and 5, to a large extent). Anticipated regret was measured for each decision choice.

Decision avoidance

To operationalize decision choice, two vignettes (see below) were created requiring decisions representative of law enforcement officers’ responsibilities, with input from a subject matter expert (Police Chief from Midwestern town). The scenarios varied based on the nature of the decision, with one being of a more critical nature. That is, one situation required making a decision about the use of force in a domestic violence situation, while the other required a decision about issuing a speeding ticket. The situations allowed participants to indicate decision choices from a list of alternatives (2 for the ticket, and 10 for the domestic violence scenario).

Officers in the domestic violence condition were given choice options based on the use of force continuum. This allowed them to make decisions about actions in a non-dichotomous fashion. The continuum is broken down into ten levels: none, command, threat, pat down, handcuffing, firm grip, pain compliance technique, takedown maneuver, strikes with the body and strike with external mechanisms (Terrill 2001). Ten alternatives were created based on the continuum, to be relevant to the scenario. Officers were given options ranging from ‘command’ to ‘shoot’. These alternatives were reviewed and concluded (by the SME) to be reasonable, during the piloting process. Decisions of not issuing a ticket and not shooting were coded as ‘avoidant behavior’ for analysis purposes, thus making the dependent variable a similar dichotomous variable for both scenarios. For the domestic violence scenario, the options were collapsed so as to allow all but one option being avoidant; that is, the shoot option. This was due to limited variance on the dependent variable. Specifically, within the domestic violence scenario 78% of the officers (n = 45) decided not to shoot while 22% (n = 13) decided to shoot. Of the 13 officers, 85% (n = 11) chose an option less than 9 (use of non-lethal weapon).

Ticket scenario: You are conducting a routine traffic operation on a Thursday afternoon when your speedometer identifies the first speeding driver for the afternoon. You decide to follow the driver who continues in excess of 20 miles over the posted speed limit for 3 blocks. The operator of the vehicle ignores your repeated efforts to effect the traffic stop, continuing to drive ignoring your instructions. It appears the driver is attempting to elude. After one minute of continuous driving, the driver pulls over and you are not very happy with the length of time it took for this person to respond to your siren. You step out of your vehicle and walk towards the driver’s side of the vehicle with ticket pad in hand. You are certain this person deserves a ticket and are annoyed by his/her lack of concern and respect for the law. As soon as you stop by the door, the window rolls down. You see a crying middle-aged lady who frantically shakes her head and begins speaking, “good afternoon Sir, I…” You stop her mid-sentence, “Are you okay, ma’am?” She begins explaining that she did not notice she had been speeding until she noticed your siren. You are faced with the decision of giving this lady a ticket. |

Domestic violence scenario : You are traveling south on Washington Avenue, when you are radioed to a domestic violence incident involving a male and female at 345 Cornell Street. While on route to the call, dispatch informs you that two other officers were already at the scene engaged in a fight with the male. You later arrive at the scene and rush to assist the two other officers when you are approached by an angry female. Without any warning the female takes a swipe at you with a broken bottle. You tell her to drop the bottle but she refuses, and continues to advance towards you. |

Decision quality

To achieve a rating of decision quality, 6 SMEs (police chiefs and superintendents) were asked to read and provide ratings of the decision options presented to participants. Ratings were made on a 5-point scale ranging from poor (1) to excellent (5). Once these ratings were collected, the intra-rater reliability was determined by examining the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICCs) for the 6 raters. Ratings from 5 raters were kept (r = .70). The mean for each decision option was calculated and assigned as participant scores based on matching responses. For example, expert ratings of a decision to issue a ticket had a mean rating of 2.67. Therefore, officers in the ticket condition who indicated this option were assigned 2.67 as their decision quality score. Given that expert ratings were provided by U.S. personnel, decision quality was only applied to analyses conducted on the U.S sample to avoid any issues with generalizability.

Results

Descriptive statistics were run on demographics, each of the five decision-making styles and corresponding behavior outcome and anticipated regret. Pearson correlations or point-biserial (as appropriate) correlations were conducted in order to examine the relationship between the demographic variables, the independent variables, the mediator and the dependent variables. The means, standard deviations and variable correlations for the full sample are reported in Table 1.

Demographics

Results showed some significant correlations with demographic variables. Firstly, gender was found to be positively related to location, r(119) = .31, p < .01, such that more female police officers were seen in Jamaica than the U.S. Additionally, Jamaican officers reported longer work hours than those in the U.S., r(118) = .24, p < .01.

Regarding demographics and avoidant decision-making style, there was a positive correlations between location and avoidant decision-making (r(118) = .27, p < .01) such that Jamaican police officers were observed as being more avoidant.

Hypothesis Testing

To assess our Hypotheses (1-4) and Research Question 1 (conditional effect of country) simultaneously, we tested a moderated-mediation model using Preacher and Hayes (2012) method to calculate bootstrapped effects. This approach, which facilitates the estimation of an indirect effect using normal theory and a bootstrap approach is considered superior to a combination of Baron and Kenny’s (1986) mediational analyses and the Sobel test (Preacher and Hayes 2004). Additionally, the PROCESS macro used for our analyses allows the testing of mediation using maximum likelihood logistic regression (for dichotomous outcomes) (Hayes 2012). We tested whether the effect of avoidant decision-making style on decision avoidance was mediated by anticipated regret. Additionally, we included country as the moderating variable (Jamaica vs. the United States) in order to examine our first research question. Using this approach, mediation is significant if the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the indirect effect is above 1. Results indicated that using a 5,000 bootstrapped sample, the CI for the indirect effect was not above 1; thereby demonstrating no moderated-mediated relationship. Results can be found in Table 2.

An examination of the data indicates that while a significant effect was observed, the direction of the effect was counter to the prediction made. That is, rather than being positively related to avoidant decisions, avoidant decision-making style shared a negative association with the outcome (-.0.25) once the mediator was added in model 2.

Reverse Causation Analyses

Given the unexpected direction of the results observed, it was felt that a reverse causal relationship between the mediator and the outcome could exist. Kenny (2012) highlights that when the mediator and outcome variables are not manipulated, as in this case, the direction of the effect may be uncertain. It is therefore suggested to retest a mediation model by interchanging the variables.Footnote 1 We thus decided to test the mediational model with anticipated regret as the outcome and avoidance as the mediating variable in order to be more confident about the direction of the effect observed. In this case we suspected that the outcome, decisions of extreme action, may be the factor causing feelings of anticipated regret. To test this, anticipated regret was examined as the outcome variable and avoidant decision (dichotomous) as the mediating variable. A logistic mediational analysis was conducted using Herr’s (2013) SPSS syntax which allows the test of mediational analyses with a dichotomous mediator (avoidant decision) based on the Baron and Kenny (1986) method. Results for this model can be found in Table 3. While the pattern of results indicated a partial mediation effect, this was not confirmed by a follow-up Sobel test (z = .93; p = .35). This provides more confident support for our former findings of anticipated regret being the mediating variable.

Additional Analyses

With the confirmation of a mediated relationship, we proceeded to examine our second research question related to decision quality across scenarios. The means, standard deviations and correlations for the Unites States sample are reported in Table 4.

Correlational analyses showed some significant correlations with demographic variables. For example, police officers working longer hours were more likely to respond with a decision to discharge their weapon if faced with the domestic violence situation described, r(70) = .35, p < .05. Expert ratings of decision quality were included for analysis with the U.S. sample. Mean ratings for each decision option can be found in Table 5. There was a negative correlation between years of experience and decision quality such that more experienced officers were less likely to indicate they would make the most appropriate decision given the situations described, r(70) = -.25, p < .05. Decision quality also correlated negatively with general avoidant decisions (r(70) = -.66, p < .01) and shoot decisions, specifically (r(70) = -1.00, p < .01); such that, avoidance was generally determined by the experts as being the better option. However, a closer look at the expert ratings of decision quality reveal that issuing a ticket (not avoiding) was a better decision (M = 2.67) than being avoidant. Conversely, shooting (M = 1.83) was rated as less suitable an option than several of the avoidant options (yell, threaten, grab, wristlock, non-lethal). Therefore, experts determined that the suitability of avoidance varied by situation.

The Preacher and Hayes (2012) method was used to examine our second research question. We were interested in determining whether scenario type (ticket or shoot) would influence the relationship between avoidant decision-making style and decision outcome, as mediated by anticipated regret. This time, we examined decision quality as our outcome by transposing expert ratings of decisions to police officers’ scores. That is, participants’ values on the dependent variable (avoidance) were used to create a new variable based on the mean ratings of decision quality (5-point scale) from Police Chiefs and Superintendents. Given the finding of a mediated relationship, we decided to follow suit by testing a moderated-mediation between avoidant decision style and decision quality (continuous) as mediated by anticipated regret. Scenario was included in the model as a moderator. Table 6 shows results of this analysis which also indicated a significant mediated role of anticipated regret on the relationship between avoidant decision-making and decision quality. Scenario type did have a significant effect on decision quality; however; an examination of the confidence intervals suggests this was not a significant moderating effect.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to identify the extent of the influence of anticipated regret on the decision-making process within law enforcement. The goal was to explore if anticipated regret mediated the relationship between the avoidant decision-making style and the decision to avoid. Additionally, the influence of anticipated regret was compared across countries and decision-making scenarios of varying degree of consequence. Participants were presented with one of two hypothetical decision-making scenarios—a domestic violence and ticket scenario, and asked to make a decision. Participants’ decision-making style, anticipated regret and chosen behavioral outcome were measured. Overall, anticipated regret was found to play a significant role in the decision-making process; there were also some unexpected relationships observed in the results.

The data showed some skew in responses resulting in the options for the domestic violence scenario having to be collapsed so as to allow all but one option being avoidant; that is, the shoot option. It is quite possible that contextual influences or constraints were responsible for range restriction on these decisions, but in different ways. In the ticket scenario, likely departmental norms regarding when to issue a ticket and when to allow latitude overrode the officers’ decision-making processes. In fact, ratings from police chiefs based on the context of the situation described, largely agreed that the decision to issue the ticket was the superior choice consistent with training. This explained why officers in the study might have chosen not to avoid issuing the ticket.

In the domestic violence situation which saw most officers using non-lethal force, this restriction could have been the result of a choice to use the maximum amount of force necessary for the situation which exceeded the use of a wristlock (option 8), but was unwarranted of a decision to shoot. Again, expert police officers suggest that the decision to use non-lethal force in the scenario described was in fact the most suited based on training. Research by Garner and Maxwell (n.d) reveals that the use of a gun as a weapon across six different jurisdictions had a frequency of only 0.1% during arrest situations. Officers were more likely to twist a suspect’s arm (1.6%), or grab a suspect (6.1%) than discharge a weapon or make a command (1.3%). The use of a non-lethal weapon, of a comparatively similar extent of force to grabbing or twisting an arm, appears consistent with use of force norms.

Discussion of Hypotheses

Decision-makers are more likely to experience anticipated regret for decisions which are irreversible (Zeelenberg 1999). Coupled with that, irreversibility of decision outcome has been found to contribute to anticipated regret (Anderson 2005). As such, the current study expected to find a relationship between the decision-making style of avoidance and anticipated regret such that, the more irreversible a decision outcome, the more anticipated regret would be present.

It was found that anticipated regret was reported more strongly among officers with an avoidant decision-making style. Tversky and Shafir’s (1992) finding of decision avoidance being more likely in situations offering multiple options may explain the reason for the presence of decision avoidance within the work of law enforcement officers who are often faced with several alternatives when making decisions. Furthermore, the nature of police work, specifically the presence of significant others in the decision environment and placing a high degree of social responsibility on officers, highlight two factors contributing to an increase in anticipated regret (Zeelenberg 1999).

The results of this study did not find support as expected for Hypothesis 3. However, there was a negative relationship between anticipated regret and the tendency to avoid (relationship approached significance). Therefore, officers of an avoidant decision-making style were more willing to issue a ticket or shoot and experienced more anticipated regret. There are a number of possible explanations for this. Firstly, as pointed out above, the restriction of range in decision within the sample could have contributed to this surprising finding (Levin 1972). However, a second explanation of this could be the contextual differences associated with police work.

An attention to the role played by context has been called for in emotion research (Jordan et al. 2010) and has been highlighted in the domain of forensic science (Dror and Charlton 2006; Kassin et al. 2013). Law enforcement officers are faced with unique challenges on a daily basis. These include the need to make a range of decisions, some life-threatening and emotionally-laden. Given the nature of these circumstances, officers may therefore be required to act outside their normal tendencies; for example, being forced to make a decision to shoot as opposed to avoiding such an action. The expectation of regret when acting outside of one’s normal decision-making mode, as observed in this research implies that this additional effort has some emotional ramifications. The expectation of regret—counterfactual thinking had one chosen differently (Dijk and Van Harreveld 2008)—with its implied personal responsibility, may therefore forecast self-blame. That is, officers may be more likely to assume responsibility, thus blame, for an action they expect to be remorseful about. Specifically, for officers who prefer to avoid, when faced with situations where avoidance isn’t a real option, one would expect more regret to surface. As discussed above, it is likely that for the ticket scenario, there were strong constraints against not giving a ticket and thus, officers felt as if they had no choice but to act accordingly. In the domestic violence scenario, although avoidance was statistically captured (anything less than shoot); conceptually, the next highest decision choice on the use of force continuum (use of non-lethal weapon) really isn’t a true ‘avoid’ choice. Officers again, given the scenario, did not really have an option to avoid, given the severity of the situation. Thus, those who really do prefer to avoid, naturally experience more regret when they can’t due to contextual factors.

The tendency of acting counter to one’s tendencies may have other implications related to emotional health. Authenticity, or acting in accordance with one’s dominant tendency (Harter 2001) has been seen to contribute to positive outcomes while inauthenticity tends to do the opposite (Cole 2001). Research examining the effects of inauthenticity in the workplace has found negative relationships between inauthenticity and time spent at work and job involvement. Additionally there was a positive relationship found with feelings of depression and inauthenticity (Erickson and Wharton 1997). Legitimately, officers acting in an ‘inauthentic’ way expected more regret as seen in the meditational analysis. Making a decision to shoot when one would have normally avoided such an action, represents great incongruence which may increase the possibility of feelings associated with counterfactual thinking.

Contextual Factors

We found no significant cross-cultural differences in our results regarding our primary conceptual models but noticed differences regarding the use of avoidant decision-making style between the two samples. Additionally, we suspect that future research with a larger sample size may find interesting cross-cultural effects. A potential explanation for an effect may be provided by the application of Hofstede’s (1984) cultural value differences between Jamaica and the United States. As previously mentioned, the United States is marked by more self-sufficient individuals with a higher preference for avoiding uncertainty in comparison to Jamaica. While not included in our analyses, these cultural differences may be applied to providing an explanation for differences observed between the two countries.

Decisions made under conditions of uncertainty are often associated with more regret (Kramer & Stone, 2011). With the Jamaican culture being more accepting of conditions of uncertainty, an aversion to regret may be limited. That is, the Jamaican culture may facilitate less preoccupation with negative counterfactual thinking as deviance from the norm is more tolerable. Police officers in Jamaica may therefore be less likely to anticipate regretting a decision in an uncertain situation. In contrast, police officers in the United States may anticipate more regret which may increase the chances of this influencing decision-making process.

Our data suggests some difference in decision-making quality across scenarios in the United States sample. While not significant based on the confidence intervals observed, the direction of the effects suggests that officers given the domestic violence scenario made better decisions than those given the ticket scenario. Potentially, in light of the severity of consequence inherent in a decision to discharge a weapon, officers with an avoidant tendency are more likely to deliberate longer when deciding. Or, perhaps there is a relationship between making better decisions in crisis situations and an avoidant tendency. Additionally, these decisions were influenced by the anticipation of regret. This implies that the role of emotions in decision-making may have some positive implications for future work on decision-quality. More directly, proper emotional training may help to enhance police decision-making.

Practical Implications

The results of this study bring to light the importance of attention towards decision-making in law enforcement and specifically the role emotions play in this process. Not only are a significant number of police officers’ job-related tasks associated with making decisions (O*NET 2013), but officers are also faced with decisions of varying severity of consequences. Therefore, a need is apparent for careful decision-making training under different conditions of severity and emotionality which would seem to be critical for effective police work. Coupled with this is the implication of including decision-making skills as a criterion in the selection within law enforcement.

A second clear implication of this research is the role played by emotion, both experienced and anticipated, in the decision-making process within law enforcement. The unique findings observed illustrate that the nature of police work introduces distinctive circumstances which may require further exploration of the nature of the impact of emotion on the process. Notwithstanding, given the already emotionally laborious nature of police work (Daus and Brown 2012; Rafaeli and Sutton 1987), the added emotionality of the decision-making process has strong implications for the design of emotional management training. Daus and Cage (2008) highlight a need for including emotional training in human resource processes through initiatives geared at focusing attention towards the relevance of emotional skills in the workplace. Selection and training for law enforcement officers may therefore include a component focusing on the management of emotions in the decision-making process.

While law enforcement represents one profession, the clear role of emotions in decision-making may also extend to other professions. Therefore, decision-making training including an emotional component may also be relevant across other professional organizations. For example, emotional management training such as that used in military settings (Linkh and Sonnek 2003), which attempts to identify individuals’ current anger management strategies could be applied to law enforcement decision-making. This may be relevant in developing more facilitative anger management strategies.

Limitations

Given the small size of the police departments from which data were gathered, the researchers had some trouble recruiting participants as there was a stated concern regarding the ability of participants to remain anonymous. While participants were reminded that the data would only be seen and used by the researchers, there was some uneasiness reported at one police department. Fowler (1995) argues that doubts of a guarantee of confidentiality by participants may result in a tendency towards socially desirable responses. Therefore, this concern serves as a possible limitation to the present study. The limitation of having a small sample size may have also affected the issue with restriction of range as discussed above.

Additionally, the ability of generalizing these findings to organizations in general may be restricted given the focus of this study on law enforcement, specifically. The findings reveal that the work of police officers is conducted under unique circumstances. Therefore, while it is clear that emotions are important in the decision-making process in law enforcement, the exact nature of these relationships may not necessarily be applicable to those in other work settings. As such, replications of this and similar studies would be better able to provide insights into the role of anticipated regret and other emotions on decision-making processes in the workplace. Notwithstanding, this study highlights the value of doing so, and especially in occupations requiring moderate to high risk decisions.

Another limitation of our study is the nature of the dependent variable used. Rather than being a measure of actual decision, we measured predicted decision. Therefore, our scenario-based methodology presents some limitations regarding external validity. However, our data was collected from experienced police officers which lend some credence to its validity. That is, experts are said to engage in more concrete reasoning and are more mindful of uncertainties (Calderwood et al. 1987).

Future Research

This research supports the need for further exploration of the nature and impact of emotions on the decision-making process both within law enforcement and in other professions. Highlighted by the findings above was a tendency of officers with an avoidant decision-making style to be less likely to engage in avoidant behavior in decision-making when experiencing anticipated regret. Further research exploring the reason for this relationship as well as the potential effects of this on officers’ well-being and ability to make effective decisions is warranted. Additionally, this research examined the role of anticipated regret on predicted decision-making. Future researchers may also find it useful to explore the actual post-decisional or experienced regret on current and future job performance.

Notes

We thank Scott Highhouse for this recommendation after reviewing a previous version of this manuscript.

References

Alloy L, Abramson L (1979) Judgment of contingency in depressed and non-depressed students: Sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 108:441–485

Anderson C (2003) The Psychology of doing nothing: Forms of decision avoidance result from reason and emotion. Psychological Bulletin 129:139–167

Anderson C (2005) The functions of emotion in decision-making and decision avoidance. In: Baumeister R, Loewenstein G, Vohs K (eds) Do emotions help or hurt decisions? Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Anshel MH (2000) A conceptual model and implications for coping with stressful events in police work. Criminal Justice and Behavior 27:375–400

Baron R, Kenny D (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51:1173–1182

Calderwood R, Crandall B, Klein G (1987) Expert and novice fire ground command decisions (KATR-858(D)-87-02F). In Final Report under contract MDA903-85-C-0327 for the U.S. Army Research Institute Alexandria, VA: Fairborn, OH, Klein Associates Inc

Cole T (2001) Lying to the one you love: The use of deception in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 18:107–129

Daus CS, Brown SG (2012) The Emotion Work of Police. Invited chapter in Ashkanasy, Hartel & Zerbe (Eds.), Research on Emotions in Organizations (pp.305–328) Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Daus CS, Cage T (2008) Learning to face emotional intelligence: Training and workplace applications. Invited chapter in Cooper & Ashkanasy (Eds.), Research Companion to Emotion in Organizations. Edward Elgar

Dijk W, Van Harreveld F (2008) Disappointment and regret. In: Ashkanasy NM, Cooper CL (eds) Research companion to emotions in organizations. Edward Elgar Publishers, London, pp 90–102

Dror IE, Charlton D (2006) Why experts make errors. Journal of Forensic Identification 56:600–617

Dror IE, Peron AE, Hind SL, Charlton D (2005) When emotions get the better of us: the effect of contextual top‐down processing on matching fingerprints. Applied Cognitive Psychology 19:799–809

Endler NS, Magnusson D (1976) Toward an interactional psychology of personality. Psychological Bulletin 83:956–974

Erickson RJ, Wharton AS (1997) Inauthenticity and depression: Assessing the consequences of interactive service work. Work and Occupations 24:188–213

Finn P, Tomz JE (1998) Using peer supporters to help address law enforcement stress. The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin 67:10–18

Fowler FJ (1995) Improving survey questions: Design and evaluation (Vol. 38). Sage

Fredin A (2008) A study of whistleblowing inaction using decision avoidance and affective forecasting theories: Effects of financial vs. other types of wrongdoing (Doctoral Dissertation). Available from the Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 3330849)

Gambetti E, Fabbri M, Bensi L, Tonetti L (2008) A contribution to the Italian validation of the General Decision-making Style Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences 44:842–852

Garner J, Maxwell C (n.d.) Measuring the amount of force used by and against the police in six jurisdictions. Retrieved from http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/176330-2.pdf#search=%22use%20of%20force%20continuum%22

Golin S, Terrell F, Johnson B (1977) Depression and the illusion of control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 86:440–442

Harter S (2001) Authenticity. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ (eds) Handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press, London, England, pp 382–394

Hayes A (2012) PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/introduction-to-mediation-moderation-and-conditional-process-analysis.html

Herr N (2013, December 4) [Web log message]. Retrieved from http://www.nrhpsych.com/mediation/logmed.html

Hofstede G (1984) Culture's consequences: International Differences in Work-related Values (Vol. 5). Sage

Janis L, Mann L (1977) Decision making: A psychological analysis of conflict, choice and commitment. The Free Press, New York

Jordan P, Dasborough M, Daus C, Ashkanasy N (2010) A Call to context. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice 3:145–148

Kassin SM, Dror IE, Kukucka J (2013) The forensic confirmation bias: Problems, perspectives, and proposed solutions. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition 2:42–52

Kenny D (2012, April 3) Mediation. Retrieved from http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm

Kohn PM (1996) On coping adaptively with daily hassles. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS (eds) Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications. Wiley, New York, pp 181–201

Kop N, Euwema MC (2001) Occupational stress and the use of force by Dutch police officers. Criminal Justice and Behavior 28:631–652

Ku G (2008) Learning to de-escalate: The effects of regret in escalation of commitment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 105:221–232

Levin J (1972) The occurrence of an increase in correlation by restriction of range. Psychometrika 37:93–97

Linkh DJ, Sonnek SM (2003) An application of cognitive-behavioral anger management training in a military/occupational setting: Efficacy and demographic factors. Military Medicine 168:475–478

Mischel W (1973) Toward a cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychological Review 80:252–283

Mohammed S, Schwall A (2009) Individual differences and decision making: What we know and where we go from here. International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology 24:249–312

Ng CK, Wong KF (2008) Emotion and organizational decision-making: The roles of negative affect and anticipated regret in making decisions under escalation situations. In: Ashkanasy N, Copper C (eds) Emotions in Organizations. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 45–60

O*Net Online (2013) Details Report for: 33-3051.01 - Police Patrol Officers. Retrieved (2013, October 9) from http://online.onetcenter.org/link/summary/33-3051.01

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2004) SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 36(4):717–731

Rafaeli A, Sutton R (1987) Expression of emotion as part of the work role. Academy of Management Review 12:23–37

Salo I, Allwood CM (2011) Decision-making styles, stress and gender among investigators. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 34:97–119

Scott S, Bruce R (1995) Decision-making style: The development and assessment of a new measure. Educational and Psychological Measurement 55:818–831

Taylor SE, Brown JD (1988) Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin 103:193–210

Terrill W (2001) Police coercion: Application of the force continuum. LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC., Indianapolis

Thunholm P (2003) Decision-making style: Habit, style, or both? Personality and Individual Differences 36:931–944

Thunholm P (2008) Decision‐making styles and physiological correlates of negative stress: Is there a relation? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 49:213–219

Tversky A, Shafir E (1992) Choice under conflict: The dynamics of deferred decision. Psychological Science 3358:358–361

Union ACL (1992) Fighting police abuse: A community action manual

Zeelenberg M (1999) Anticipated regret, expected feedback and behavioral decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 12:93–106

Acknowledgements

We thank Scott Highhouse for his comments on a previous version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, S., Daus, C. Avoidant But Not Avoiding: The Mediational Role of Anticipated Regret in Police Decision-making. J Police Crim Psych 31, 238–249 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-015-9185-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-015-9185-2