Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this systematic review was to describe and examine the current use of treatment summaries and survivorship care plans (TSs/SCPs) for cancer survivors, as well as to summarize and critically assess relevant literature regarding their preferences and usefulness. There is a knowledge gap regarding the preferences of stakeholders as to what is useful on a treatment summary or survivorship care plan.

Methods

A systematic review of eligible manuscripts was conducted using preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Relevant studies were identified via PubMed, CINAHL Plus, and the Cochrane Library from 2005 through 2013. Eligible studies were critically appraised with qualitative and quantitative appraisal tools.

Results

There were 29 studies included in this review; 19 were quantitative. Survivors and primary care physicians preferred a printable format delivered 0 to 6 months posttreatment and highlighting signs and symptoms of recurrence, late, and long-term effects, and recommendations for healthy living. Oncology providers supported the concept of treatment summary and survivorship care plan but reported significant barriers to their provision. No studies incorporated caregiver perspectives of treatment summary and survivorship care plan.

Conclusion

This systematic review did not reveal conclusive evidence regarding the needs of survivors or providers regarding treatment summaries and survivorship care plans. A lack of rigorous studies contributed to this.

Implications for cancer survivors

Treatment summaries and survivorship care plans are useful for cancer survivors; however, future rigorous studies should be conducted to identify and prioritize the preferences of survivors regarding these.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction/background

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, helped galvanize the oncology community to recognize and address unmet needs of cancer survivors [1]. The report, which conceded a deficit in knowledge and responsiveness of oncology providers concerning cancer survivorship, stated that the essential components of survivorship care were to prevent, detect, and provide surveillance of new and recurrent cancers, coordinate care between oncologists and primary care providers, and ensure that survivors were given information on late and long-term effects of cancer treatment modalities [1].

In support of the essential components of survivorship care, the IOM panel presented 10 recommendations, one of which stated, “Patients completing primary treatment should be provided with a comprehensive care summary and follow-up plan that is clearly and effectively explained. This ‘Survivorship Care Plan’ should be written by the principal provider(s) who coordinated oncology treatment” ([1], p. 4). The IOM’s rationale for advocating for the record of care and comprehensive follow-up plan, respectively termed treatment summary (TS) and survivorship care plan (SCP), was to enhance care coordination among oncology providers, cancer survivors, their caregivers, and primary care providers (PCP), to ensure that the 10 million cancer survivors were not lost to “systematic follow-up within our health care system and opportunities to effectively intervene are missed” ([1], p. 4). This is still essential, as there are currently 14.5 million cancer survivors in the USA, with the number expected to increase to nearly 19 million by 2024 [2].

Key stakeholders such as the National Cancer Institute’s Office of Cancer Survivorship, American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), American Cancer Society (ACS), National Comprehensive Cancer Network, National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, Oncology Nursing Society, and LIVESTRONG™ embraced and endorsed the IOM recommendation for the provision of TS/SCP to survivors and their PCPs. During the past 9 years, several of these organizations and others created TS/SCP templates for use by either oncology health care providers or survivors. The most well-known TS/SCP template originated from ASCO and is available for download [3]. Others include Journey Forward [4], the LIVESTRONG™ care plan via Penn Medicine’s OncoLink [5], The Cancer Survivors’ Prescription for Living Plan [6], the Minnesota Cancer Alliance’s What’s Next? Life after Cancer Treatment [7], and the Foundation for Gynecologic Oncology’s Survivorship Toolkit, which is sponsored by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology [8]. Additionally, the American College of Surgeon’s Commission on Cancer (CoC) 2012 standards (standard 3.3) required accredited cancer institution members to implement TS/SCPs by 2015 for cancer survivors who completed active treatment [9].

Despite the endorsements and creation of TS/SCP templates, implementing TS/SCPs as a standard of care has been slow. Most oncology programs in the USA have adopted TS/SCPs in some capacity [10, 11]; however, use of care plans remains inconsistent across health care systems and programs [12, 13]. Two national studies indicated that nearly half of oncologists always or almost always provided TS [11], while only 10–20 % always or almost always provided SCP [11, 14]. However, nearly two thirds of oncologists reported discussing care recommendations with cancer survivors [14]. In September 2014, the CoC amended standard 3.3 from the expectation that 100 % of cancer survivors who completed active treatment receive a TS/SCP to a phased implementation of providing SCPs because member institutions indicated in a survey that only 21 % were prepared with a process and plan for compliance [15].

While the IOM’s recommendation for TS/SCP was commendable, the pragmatism of TS/SCP remains unproven. Recently, an integrative review [16] and a systematic review [17] of studies, both of which focused on SCP outcomes, concluded that (1) there were a limited number of rigorous scientific studies looking at feasibility and effectiveness of TS/SCP and (2) there was negligible evidence of improved short- or long-term patient-reported outcomes (PROs) that can be tied to TS/SCP [16, 17]. The reasons for the lack of supporting evidence for the efficacy of TS/SCP remain unclear, but a growing body of literature suggests that there are significant barriers to the feasibility, acceptability, and implementation of TS/SCP [10, 16, 18, 19].

Notwithstanding the lack of evidence, oncologists and PCPs agree that a SCP is theoretically beneficial [20–22]. Yet, there is little consensus on (1) the template, (2) format, (3) content, (4) time at which TS/SCP should be provided to survivors, (5) metrics for outcome evaluation, and (6) the provider who should be responsible for delivery of the SCP to patients [21–23]. The main impediments correlated with the lack of delivery of TS/SCP are the length of time and breadth of resources needed for an oncology practice to provide a personalized TS/SCP for a single survivor [17, 21, 24, 25].

One may infer that the significant amount of time needed to complete individualized documentation (median time of 30–60 min) of the TS/SCP and review the document with the cancer survivor (median time of 30–60 min) [12] is related to the numerous items recommended for inclusion in the original IOM report. The IOM fact sheet from the 2005 report suggested 18 components for the TS/SCP (7 for the record of care and 11 for the care plan), each of which were bullet points containing multiple elements to be documented [1]. In an effort to create a metric scorecard, Palmer and colleagues identified 92 separate items for inclusion on a TS/SCP (60 for the TS, 32 for the SCP) based upon the IOM report recommendations [19]. A number of factors impair the ability to provide TS/SCP to survivors: disparity and variability amongst practice settings (i.e., academic, community, urban, and rural), access to electronic health records, computerized TS/SCP programs such as Journey Forward, staffing, approval and support among practice setting administrators, and myriad other factors [24, 25].

Evidence is emerging regarding the lack of utility and/or benefit of TS/SCP for patients and PCPs, particularly for PRO [16, 17]. Despite these findings, a study from Hewitt et al. [22] suggested that cancer survivors and PCPs found TS/SCP to be useful. The perspective of these key stakeholders is paramount to the successful implementation of TS/SCP and, as such, necessitates further exploration of the preferences of cancer survivors, their caregivers, and health care providers. The purpose of this systematic review was to describe and examine the current use of TS/SCPs for cancer survivors, as well as to summarize and critically assess relevant literature regarding the preferences and usefulness of the care plans that are currently in use. It asked the following questions: (1) How are cancer TS/SCP used in clinical practice? (2) What are characteristics of cancer TS/SCP? and (3) What are the preferences and usefulness of TS/SCP from the perspectives of cancer patients, caregivers, and oncology health care providers? This paper lays the groundwork for the use of evidence-based SCP in clinical practice, which is an essential step in improving the quality of cancer survivorship care.

Methods

Literature search strategy

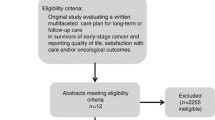

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) were used as guidelines in this systematic review [26]. A search strategy (Fig. 1) was used to identify studies involving cancer SCP incorporating preferences of health care providers, patients, and their caregivers regarding information to be included in these plans in the following electronic databases: PubMed (US National Library of Medicine); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus with Full Text (EBSCO), and the Cochrane Library (Ovid). Search parameters included English-only publications between 2005 and 2013, which was consistent with the publication date of the Institute of Medicine’s report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition [1].

Though “cancer survivorship care plans” is an often-used phrase within oncology, it is not a Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) phrase. As such, a combination of MeSH terms and keywords related to information preferences on cancer SCP was employed. Due to the lack of specificity of some of the key words for oncology and/or SCP, the search was further refined with additional key words (e.g., cancer treatment summary, survivorship, coordination of care) if more than 1500 records were identified.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review included studies that were (1) published between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2013; (2) published as original work in a peer-reviewed journal; (3) written in English; and (4) contained qualitative or quantitative data related to preferences of items to be incorporated on cancer SCP by adult-aged (18+ years) persons identified to be (a) diagnosed with any type or stage of cancer, (b) a family member of one who has cancer and/or caregiver, or (c) health care provider (e.g., primary care physician, oncology physician, advanced practice professionals). Studies were excluded if (1) the topic addressed palliation, end of life, or hospice treatment; (2) they pertained to survival and/or mortality statistics; (3) the targeted sample was adolescent or pediatric cancer survivors, their caregivers, or health care providers (because survivorship care for the pediatric oncology population uses and addresses unique issues of age-related physical and psychosocial development significantly different than adult-aged populations); (4) they related to the provision of survivorship clinical care unrelated to SCP content; or (5) they were secondary works (e.g., review articles, book chapters, poster abstracts, commentaries, editorials, case reports, or dissertations/theses).

Study selection

The schema for study selection is delineated in Fig. 2. One reviewer (first author) initially screened all non-duplicative study titles with dichotomous ratings (yes/no) for inclusion in the review. Subsequently, two reviewers (first and second authors) independently read and considered 363 abstracts for inclusion in the review with the same categorical rating structure. An inter-rater reliability analysis using the kappa statistic was performed to determine consistency between the two reviewers [27]. Disagreements in ratings between the two reviewers, which occurred in less than 13 % of all reviewed abstracts, were resolved by consensus. There was moderate agreement between two independent reviewers (first and second authors), κ = 0.502 ± 0.061 (95 % CI, 0.382, 0.622), p < 0.000. Selected studies were further scrutinized for inclusion subsequent to data abstraction.

Data abstraction

Data on relevant study characteristics, such as study objectives and design, selection criteria, sample size, theoretical framework (if applicable), outcome measures, and any statistically significant and/or summarized results, were independently extracted from each study by two reviewers (first and second authors) and catalogued using spreadsheet software. These two reviewers then independently rated each study for inclusion, and inter-rater reliability was calculated using the kappa statistic. Of the 47 studies identified for full-text review, the reviewers had near perfect agreement (κ = 0.905 ± 0.065, 95 % CI (0.78, 1.0), p < 0.000) for the inclusion of 29 studies published between 2007 and 2013. In a further effort to reduce bias, 10 % of the sample (n = 4) was randomly selected for independent ratings by a third reviewer (third author). There were no discrepancies in agreement when compared to the first two reviewers’ decisions of the same studies.

Critical appraisal methods

Critical appraisal tools differed for quantitative and qualitative studies. The quality of quantitative studies (n = 19) was evaluated using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (QAQTS) from the Effective Public Health Practice Project [28]. Two reviewers (first and second authors) used the QAQTS tool to independently assess and rate each study in the following areas as “strong,” “moderate,” or “weak” by predetermined criteria from the QAQTS dictionary [29]: (a) selection bias, (b) study design, (c) confounders, (d) blinding, (e) data collection methods, and (f) withdrawals and dropouts. A fourth option of “not applicable” was used for sections (c) and (d) for those studies that did not include more than one group. Each study was then assigned a global rating of strong (four strong ratings with no weak ratings), moderate (less than four strong ratings and one weak rating), or weak (two or more weak ratings). The two reviewers had a discrepancy in ratings in just one of the 19 (5 %) studies, which was resolved by discussion. The third reviewer (third author) independently assessed and rated two (10 %) of the quantitative studies selected by random number generation without any discrepancies in ratings. The QAQTS tool assigned low ratings to studies that had less than 60 % response rates, which consequently had the potential to decrease the global rating from moderate to weak. However, survey response research indicates that a 50 % response rate is acceptable for surveys delivered via mail, email, or web [30]. In this review, studies where acceptable survey response rates may have caused a low rating on the QAQTS tool were individually evaluated (n = 1 study), and the rating was modified.

For the qualitative studies, two reviewers (first and second authors) independently evaluated and rated the studies (n = 10) with the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI) [30]. This tool assessed 10 elements, including theoretical framework, appropriateness of research methodology, data collection and analysis, researcher bias, adequate representation of participants, ethical considerations, and strength of conclusions. Each reviewer objectively rated the paper as “include” or “exclude,” with unanimous consensus. A third reviewer (third author) independently assessed and rated one (10 %) randomly selected qualitative article, agreeing with the other reviewers for study inclusion.

Results

Study characteristics

The search of electronic databases yielded 5886 unique study citations. Most of the included studies were quantitative (n = 19); 3 were designed as randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [31–33], 1 was a pretest/posttest [23], and an additional 15 were survey studies with descriptive analyses (Table 1). The remaining 10 (34 %) of the included studies were qualitative, mostly relying on analyses of data collected via focus group and individual interviews.

Twenty of the studies (71 %) sought survivor perspectives (n = 14 studies queried survivors only; n = 6 studies had input from survivors and providers). The majority of studies included survivors diagnosed with breast cancer (n = 10), while the other studies considered persons with diagnoses of colorectal cancer (n = 3), gynecologic cancer (n = 1), or a heterogeneous group of cancer diagnoses (n = 6). Almost half of the papers included perspectives of health care providers; six included oncology providers (i.e., oncologists, nurses, and nurse practitioners), four included PCPs, and four included both. Three papers exclusively included perspectives of cancer survivors who self-identified to be minority: two with South Asian women and one with African American women [37, 47, 48]. Sixty percent of the studies were conducted in the USA (n = 18), with the remainder in Canada (n = 7), Australia (n = 3), and the UK (n = 1). There were no studies with caregiver perspectives that fit our inclusion criteria.

The variables of interest with survivors encompassed several elements, such as survivorship experiences and the quality of care received, satisfaction with survivor-physician and physician-physician communication, perceived gaps in survivorship care, and delivery of a SCP. Variables of interest with providers included provider perceptions of barriers to implementation of SCP, role clarification of which discipline should provide survivorship care, and confidence in managing cancer survivors.

Clinical use of TS/SCPs

A majority of the included studies contained information on use in clinical practice (n = 18). The overwhelming theme identified was that PCPs who received a TS/SCP, particularly the record of care, perceived that there was enhanced coordination of care with the oncology team [11, 20–22, 24, 34, 36, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46, 50, 52]. Four examined a TS/SCP clinical intervention in which participants received a SCP followed by a face-to-face review with a clinician [23, 31–33]. Two of the four studies [31, 37] randomized participants to either standard or standard practice plus a 30-min clinical visit to review the SCP. In a third study, cancer survivors who completed adjuvant therapy received an intervention with NCI’s Facing Forward: Life After Cancer Treatment as well as an in-person visit with a nurse and nutritionist to review surveillance and healthy living recommendations [33]. The final study, a 10 person pilot, developed and utilized the “survivor care” intervention in which study participants received (1) a DVD with information booklet; (2) an individualized SCP that was provided to the survivor, PCP, and oncology treatment team, (3) a face-to-face clinical visit with a nurse, and (4) three follow-up telephone calls [23]. All four of these studies (three RCTs and one pretest/posttest) did not show any significant outcomes for the intervention arm when compared to controlled groups. Thirteen studies (45 %) utilized a known TS/SCP template in the methodological design. The ASCO template (n = 5) was the most commonly used [31, 35, 37, 38, 44] followed by LIVESTRONGTM [40, 43] and Journey Forward [21, 51]. Mayer et al. [43] queried participants on their preferences of four TS/SCP templates (ASCO, Journey Forward, LIVESTRONGTM, and the South Atlantic Division of American Cancer Society SCP). The remaining studies created unique templates based upon existing survivorship guidelines [23, 32, 33, 39, 53] (Table 1).

Cancer survivor SCP preferences

Cancer survivors agreed, when asked, that TS/SCPs were useful and effective, particularly for written documentation of treatment [22, 34, 35, 38, 39, 41, 42, 51–53], while survivors’ preferences reported in Faul et al. indicated that the provision of the TS/SCP reduced worry [38]. Two studies did not show an overwhelming survivor preference of web-based/electronic TS/SCP over a printed paper copy [39, 43]; however, Mayer et al. indicated survivor preference for a face-to-face consultation [43]. A few studies suggested that the TS/SCP should be written in plain language because clinical verbiage is challenging for survivors to understand [37, 42, 43].

Survivors preferred to have specific areas of concern addressed on a SCP, such as information on signs and symptoms of recurrent cancer, fatigue, cognitive changes, depression, anxiety, spiritual guidance, and relationship changes (particularly marital strife) [22, 41, 42, 48, 49, 51]. Survivors also requested improved communication of information on healthy living recommendations, such as nutrition and exercise, late and long-term effects, a record of care/treatment summary, and which provider is responsible for follow-up testing and care [37, 49, 51]. In Dulko et al. [21], half of respondents thought that they received the TS/SCP at the appropriate time (completion of active treatment) while survivors’ perspectives reported in Mayer et al. stated the optimal time was 3 to 6 months posttreatment [43].

PCP SCP preferences

Several studies suggested that PCPs overwhelmingly believed that TS/SCP were useful as a communication tool between the oncology and primary care teams [20, 22, 34, 39, 43, 45, 46, 50, 52]. This is particularly true regarding the provision of the cancer staging characteristics and treatment overview when presented in a concise and abridged manner [20, 40, 43, 46, 50]. Of the studies that asked, PCPs did not have a strong preference for electronic copies, particularly if they already had access to the electronic record [43–45]. However, one study noted that some PCPs preferred a paper record to place in the patient’s chart [45]. Some studies suggested that the pools of PCP respondents were uncomfortable with the provision of surveillance and survivorship care, citing knowledge deficits in oncology care [34, 39, 45, 46]. These studies directly contrast Hewitt et al. [22] and Smith et al. [50], in which the majority of PCPs stated that they were comfortable with providing survivors survivorship care, and cited doing so as an “important role” in the provision of posttreatment care. As reported in Salz et al. [45], at least 50 % of respondents indicated that all 45 items recommended by the IOM for inclusion on TS/SCP were important or very important. Other studies highlighted PCP preferences for TS/SCP; these included cancer characteristics and a record of care [43, 45, 50], surveillance testing noting the designated health professional to order and follow-up on said test [20, 21, 39, 43, 45], late and long-term effects of treatment [20, 34, 43], and psychosocial information [34].

Oncology provider SCP preferences

Nine of the studies included perspectives of oncology health care providers. Six of these studies solely evaluated the perspective of the oncology health care provider [11, 21, 38, 39, 50, 52], while three studies included perspectives of nurses and other oncology support staff [22, 24, 44]. Oncology health care providers felt that TS/SCPs were useful for patients and other health care providers, but opinions varied as to what content should be included and who should be responsible for preparing the TS/SCP [21, 22, 34, 38, 53]. Three studies specifically addressed which member of the oncology health care team should complete the TS/SCP and present it to the patient. Specifically, Dulko and colleagues [21] concluded that advanced practice providers should have the responsibility to complete the documentation of the TS/SCP as well as review with the cancer survivor, while respondents in Hewitt et al. [22] thought that nurses should have the responsibility for both (e.g., this was stated by nurses in the study). Baravelli et al. [34] reported strong disagreement between two groups, in which physicians felt that they should have the responsibility of preparing and delivering the TS/SCP and nurses felt that nurses or advanced practice nurses should have the responsibility. The most reported barrier to implementing TS/SCP into clinical practice included the time to complete the SCP [22, 36, 38, 44, 53]. Other reported barriers included sustainability [36], lack of reimbursement [22], lack of consensus on format [53], and cost of documenting a TS/SCP [44].

Critical appraisal of studies

Besides the three randomized clinical trials and one pretest/posttest single group study, the remainder of the quantitative studies used a descriptive study design via questionnaires or surveys. The analysis of quantitative studies using the QAQTS tool resulted in global ratings of one strong paper [39] and four moderate papers [23, 32, 50, 52]. The QAQTS rating for survey response rates was adjusted for Smith et al. [50], as this study had a mailed survey response of 59 %, which is considered “good” for a mailed survey response [30]. This increased the global rating from weak to moderate. All other studies (n = 14) had a global rating of weak (Table 2). A majority of the weak ratings were a result of the descriptive study designs, lack of representative population samples, and lack of reliable and/or valid tools for data collection.

While none of the RCTs found significant differences on outcome measures between groups (SCP vs. no SCP), each RCT examined distinctive outcome measures. Brothers et al. [31] examined gynecologic cancer survivors’ perceptions of the quality of their oncology care and helpfulness of written material provided; Grunfeld et al. [32] examined cancer-related distress, and Hershman et al. [33] examined health worry, treatment satisfaction, and issues and changes that survivors correlated to long-term survivorship using the 81-item Impact of Cancer scale. The descriptive quantitative studies found that survivors and PCPs endorsed the use of a SCP, while oncology providers felt that SCP are time-consuming, required too many resources to produce, and did not assist in the overall patient management of survivorship care. Survivors continued to express unmet needs during their care and cited such examples as confusion as to which provider should provide survivorship care, poor long-term side effect and symptom management, and unmet interpersonal and emotional needs.

Nine of the 10 qualitative papers met at least 7 of the 10 JBI-QARI criteria (Table 3), and all used focus groups or individual interviews. Although the Singh-Carlson et al. [48] study had nearly all of the criteria present signifying the strength of the study, very few of the papers included the philosophical framework of the questions, discussed the beliefs/values of the authors, or noted how those beliefs were isolated from the analysis of the paper to minimize bias. JBI-QARI deems all of those categories essential components of a strong qualitative paper; thus, studies with these unmet criteria may not be considered high quality [54]. Finally, one paper [22] lacked rigor in several of the JBI-QARI criteria as noted by the reviewers (first and second authors).

In summary, the critical appraisal revealed that the majority of the articles were categorized as presenting weak evidence due to their design methodology of a simplistic single interaction with the participants. Only one quantitative study [33] was rated as strong, while three quantitative studies [23, 31, 32] were rated as moderate in supporting their conclusions. None of these RCTs demonstrated any statistical difference in quality of life outcomes between a control group and survivors who were given a TS/SCP. One qualitative study [48] was suggestive of a high-quality conclusion, while eight studies were of credible evidence.

Discussion

This systematic review analyzed studies designed to elucidate the preferences of cancer survivors as well as oncology and primary care providers for specific items or concepts identified as essential for inclusion on TS/SCP. This systematic review did not reveal conclusive evidence to explicate and verify the gaps or needs in TS/SCP from the perspective of cancer patients or providers. The lack of rigorous study designs and lack of consensus in the format and type of TS/SCP used contributed to the inconclusive position. However, the notable thematic findings evident across included studies suggested that patients and PCPs agreed on the pragmatism of TS/SCP as a historical summation and documentation of oncology care. Both groups preferred a printable format delivered 0 to 6 months posttreatment. Cancer survivors favored a document with plain non-clinical language that included a treatment summary, signs and symptoms of recurrence, late and long-term effects, and recommendations for healthy living. PCPs preferred a concise record of care, clearly delineating which provider would be responsible for surveillance care; yet, PCPs disagreed among themselves regarding their willingness and ability to provide oncology follow-up care. Oncology providers supported the concept of TS/SCP but reported significant barriers to the provision of TS/SCP to PCPs and survivors. These barriers included lack of reimbursement and resources to complete/provide the TS/SCP, length of time to complete a TS/SCP, as well as a national consensus of the appropriate format.

Despite these noted trends, our review highlights that a significant knowledge gap remains regarding TS/SCP preferences of cancer survivors and providers. The knowledge deficit regarding cancer survivors’ preferences includes identifying (1) which items and concepts are highly valued and should be definitively addressed on the TS/SCP; (2) any potential correlation between the high-value concepts and demographic data (e.g., age, gender, socioeconomic status, level of education, adult learning style, decision-making style); (3) what, if any, TS/SCP items could be correlated to survivor distress and what interventions would alleviate the distress; (4) the influence of TS/SCP provision on PRO and risk stratification algorithms for treatment-related late and long-term effects; and (5) the preferences of caregivers for information.

There is also limited information on how to make the TS/SCP useful to PCPs to maximize their impact on care for the survivor. For example, do PCPs prefer to receive a copy of the TS rather than receiving a several page TS that also includes a SCP? Do TS/SCP alter a PCP’s evaluation and management of survivors regarding late and long-term effects (i.e., risk stratification based on a survivor’s comorbidities and cancer treatment)? As noted in this review, there is a discrepancy among PCPs in their comfort level in caring for cancer survivors. So, what should oncology providers do to efficiently and practically address those concerns?

The preferences of oncology providers indicate that the majority preferred a designated staff member to complete the form in a timely manner (less than 20 min [20]) using an accessible template within an electronic health record [21, 24, 38, 44]. However, there are well-known reported barriers to the implementation of TS/SCP in direct contrast to the stated preferences of oncologists [10]. These included (1) time for staff to complete forms [38, 44], which in one study averaged 53.9 min [21], (2) lack of reimbursement [38, 44], (3) lack of resources and institutional processes [10, 21, 38, 40], and (4) challenges in transitioning survivors from oncology practices to PCPs [38]. Addressing the effect of these barriers on the TS/SCP process by alleviating some of the organizational constraints (i.e., resources, choosing a single template, using technology and electronic health record systems) could potentially impact and improve health care system processes by enhancing compliance in the provision of TS/SCP. National oncology organizations are beginning to acknowledge these barriers to implementation by adjusting their recommendations. In September 2014, the CoC modified standard 3.3 [15], which clarified the type of information to be included on a TS/SCP, and in October 2014, ASCO revised the TS/SCP template by condensing it to two pages [3].

Our findings are consistent with recently published reviews by Mayer et al. [16] and Brennen et al. [17], both of which failed to demonstrate that TS/SCP provision was related to favorable PRO for its recipients, despite support from nationally supported oncology organizations, health care providers, and cancer survivors. In light of those reviews in tandem with this review, a question remains: Should there be a cessation of TS/SCP? While this question is fair to ask when confronted with current evidence from the reviews and lack of TS/SCP implementation by most US cancer institutions [11–14], it is undoubtedly premature to advocate for an extreme course reversal on TS/SCP by terminating this tenet of survivorship care, particularly because cancer survivor feedback was strongly positive. Firstly, provision of TS/SCP to cancer survivors and their providers is often supported by the principle of beneficence from within the oncology community, citing it as the “right thing to do.” This idealism remains as important today as it was in 2005. Secondly, significant time and financial resources have been dedicated to the implementation of TS/SCP in the USA and globally. This includes standards set forth by credentialing bodies such as CoC and the National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers. Thirdly, as cancer survival rates continue to increase, the provision of TS/SCP becomes even more essential for survivors. Finally, the lack of scientifically rigorous studies to date precludes creating conclusive changes.

Based upon the above-noted gaps, it is imperative to demonstrate and justify evidence-based rationale for TS/SCP to (1) contribute to improved care coordination from oncology to PCPs and other specialty providers, (2) substantiate the need for reimbursement for survivorship care, (3) demonstrate cost-effective resource utilization for cancer centers, and most importantly (4) show efficacy and improved PRO for cancer survivors. Prior to further investigation on the relationship between TS/SCP and PRO, additional non-formative research should be conducted, particularly comparative effectiveness studies in diverse cancer populations to help elucidate concrete preferences of survivors and providers in an effort to develop a consistent template and format.

There were several limitations with this review, attributable to the methodologies of the studies. The majority of studies included were exploratory in nature, using formative research methodology or opinion-based questionnaires rather than assessing PRO. Survivor study participants were more often diagnosed with a solid tumor malignancy, primarily breast cancer, which narrowed the samples by gender and limited the evidence for survivors of other cancer types. Further, the studies varied widely on which SCP format was used and/or how TS/SCP was distributed to PCPs and patients. Another challenge was comparing findings from studies conducted in dissimilar international health care settings, such as the fee-for-service model in the USA compared with national health systems in Australia, Canada, and the UK, in which patients may return to their PCP at much earlier time points after treatment completion [32]. In this review, two separate critical appraisal tools were used, despite the existence of a few mixed methods appraisal tools. The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) was not chosen because the tool only had pilot data on reliability and validity [55, 56] during the critical appraisal process for this review. The JBI-QARI tool was chosen upon review of existing literature [57, 58]. The strict criteria set forth by the JBI-QARI for qualitative studies, which generally do not have highly interpretive findings, may have negatively affected a study’s strength of evidence [59]. Appraisal tools (e.g., Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) [60], Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [61], Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) [62, 63]) for quantitative studies were considered but not chosen because the tools were designed to appraise single methodological approaches; QAQTS was chosen at the recommendation of The Cochrane Review reviewer’s handbook [64]. Our systematic review methodology could be limited by the possibility that despite conducting a comprehensive literature search, we may have unintentionally omitted studies germane to the review. Studies published after December 2013 were not included. Further, because few RCTs exist on use of TS/SCP, we could not fully interpret the clinical significance of TS/SCP for cancer survivors. Also, no study addressed what gaps and/or needs cancer survivors and providers wanted addressed on a TS/SCP. Finally, our initial research question included caregiver preferences, which remains unanswered in this review, as there were no available studies that considered their perspective. Three studies that focused on caregiver perspective [65–67] were omitted because the outcomes were related to their needs and experiences rather than on the TS/SCP. Although additional empirical studies are needed in this area, our review advances the ability to organize and interpret the literature on the usefulness of TS/SCP.

Conclusion

This review exposes the lack of comprehensive or conclusive evidence, therefore confirming the need for further research and analysis if the needs of cancer survivors are to be adequately addressed. While there is consensus among cancer survivors and PCPs that TS/SCP is useful, which elements stakeholders view as essential remains elusive. The overall weakness of the evidence presented and the lack of statistical significance in RCT outcomes limit the value and utility of the findings; however, this further illustrates the need to engage in non-formative research (i.e., comparative effectiveness studies) to determine how TS/SCP improves patient and practice outcomes. It may be challenging to gain consensus among providers and survivors regarding what should be included in a TS/SCP. As such, using the existing evidence to move toward feasibility and testing of TS/SCP outcomes will hopefully advance and strengthen evidence for use of TS/SCP for survivors.

References

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2014-2015. Atlanta.

ASCO Survivorship Care Plan Template In: Cancer survivorship. American Society of Clinical Oncology. http://www.asco.org/practice-research/cancer-survivorship. Accessed December 16, 2014.

Survivorship Care Plan Builder. Journey Forward. 2014. http://www.journeyforward.org/professionals/survivorship-care-plan-builder. Accessed December 16, 2014.

LIVESTRONG™ Care Plan powered by Penn Medicine’s OncoLink. 2014. http://www.livestrongcareplan.org/. Accessed December 16, 2014.

The Prescription for Living Plan. The American Cancer Society, Oncology Nursing Society, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, American Journal of Nursing, and the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. 2014. http://www.nursingcenter.com/lnc/static?pageid=721732. Accessed December 16, 2014.

What’s Next? Life after Cancer Treatment. In: Cancer survivorship care plan. The Minnesota Cancer Alliance. http://mncanceralliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/SurvivorCarePlan3202012_Final.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2014.

Survivorship Toolkit. Society of Gynecologic Oncology. 2014. https://www.sgo.org/clinical-practice/management/survivorship-toolkit/. Accessed December 16, 2014.

Cancer Program Standards 2012, version 1.2.1: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care Manual. American College of Surgeons. 2014. https://www.facs.org/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/standards. Accessed May 13, 2014.

Birken SA, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ. Survivorship care plans: prevalence and barriers to use. J Canc Educ. 2013. doi:10.1007/s13187-013-0469-x.

Forsythe LP, Parry C, Alfano CM, Kent EE, Leach CR, Haggstrom DA, et al. Use of survivorship care plans in the United States: associations with survivorship care. J Natl Cancer I. 2013. doi:10.1093/jnci/djt258.

Stricker CT, Jacobs LA, Risendal B, Jones A, Panzer S, Ganz PA, et al. Survivorship care planning after the institute of medicine recommendations: how are we faring? J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:358–70.

Merport A, Lemon SC, Nyambose J, Prout MN. The use of cancer treatment summaries and care plans among Massachusetts physicians. Support Care Cancer. 2012. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1458-z.

Blanch-Hartigan D, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Tenbroeck S, Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, et al. Provision and discussion of survivorship care plans among cancer survivors: results of a nationally representative survey of oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2014. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.51.7540.

Accreditation Committee Clarifications for Standard 3.3 Survivorship Care Plan. In: The CoC source. American College of Surgeons. 2014. https://www.facs.org/publications/newsletters/coc-source/special-source/standard33. Accessed December 16, 2014.

Mayer DK, Birken SA, Check DK, Chen RC. Summing it up: an integrative review of studies of cancer survivorship care plans (2006-2013). Cancer. 2014. doi:10.1002/cncr.28884.

Brennan ME, Gormally JF, Butow P, Boyle FM, Spillane AJ. Survivorship care plans in cancer: a systematic review of care plan outcomes. Brit J Cancer. 2014. doi:10.1038/bjc.2014.505.

Oeffinger KC, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Smith SM, Mitby PA, Eshelman-Kent DA, et al. Increasing rates of breast cancer and cardiac surveillance among high-risk survivors of childhood Hodgkin Lymphoma following a mailed, one-page survivorship care plan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;56:818–24.

Palmer SC, Jacobs LA, DeMichele A, Risendal B, Jones AF, Stricker CT. Metrics to evaluate treatment summaries and survivorship care plans: a scorecard. Support Care Cancer. 2014. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-2107-x.

Shalom MM, Hahn EE, Casillas J, Ganz PA. Do survivorship care plans make a difference? a primary care provider perspective. J Oncol Pract. 2011. doi:10.1200/JOP.2010.000208.

Dulko D, Pace CM, Dittus KL, Sprague BL, Pollack LA, Hawkins NA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing cancer survivorship care plans. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013. doi:10.1188/13.ONF.575-580.

Hewitt ME, Bamundo A, Day R, Harvey C. Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2007. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826.

Jefford M, Lotfi-Jam K, Baravelli C, Grogan S, Rogers M, Krishnasamy M, et al. Development and pilot testing of a nurse-led posttreatment support package for bowel cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2011. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f22f02.

Salz T, McCabe MS, Onstad EE, Baxi SS, Deming RL, Franco RA, et al. Survivorship care plans: is there buy-in from community oncology providers? Cancer. 2014. doi:10.1002/cncr.28472.

Birken SA, Deal AM, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ. Determinants of survivorship care plan use in US cancer programs. J Cancer Educ. 2014. doi:10.1007/s13187-014-0645-7.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535.

Cohen J. Quantitative methods in psychology: a power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–9.

Quality Assessment Tool For Quantitative Studies. Effective Public Health Practice Project. 1998. http://www.ephpp.ca/index.html. Accessed May 13, 2014.

Quality Assessment Tool For Quantitative Studies Dictionary. Effective Public Health Practice Project. 2009. http://www.ephpp.ca/PDF/QADictionary_dec2009.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2014.

Dillman DA. Mail and internet surveys: the tailored design method. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1999.

Brothers BM, Easley A, Salani R, Andersen BL. Do survivorship care plans impact patients’ evaluations of care? a randomized evaluation with gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:554–8.

Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, Maunsell E, Coyle D, Folkes A, et al. Evaluating survivorship care plans: results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.837.

Hershman DL, Greenlee H, Awad D, Kalinsky K, Maurer M, Kranwinkel G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013. doi:10.1007/s10549-013-2486-1.

Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, Schofield P, Lotfi-Jam K, Rogers M, et al. The views of bowel cancer survivorship and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow-up. J Cancer Surviv. 2009. doi:10.1007/s11764-009-0086-1.

Blinder VS, Norris VW, Peacock NW, Griggs JJ, Harrington DP, Moore A, et al. Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment plan and summary documents in community oncology care. Cancer. 2013. doi:10.1002/cncr.27856.

Brennan ME, Butow P, Spillane J, Boyle FM. Survivorship care after breast cancer: follow-up practices of Australian health professionals and attitudes to a survivorship care plan. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1743-7563.2010.01286.x.

Burg MA, Lopez EDS, Dailey A, Keller ME, Prendergast B. The potential of survivorship care plans in primary care follow-up of minority breast cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1012-y.

Faul LA, Rivers B, Shibata D, Townsend I, Carbrera P, Quinn GP, et al. Survivorship care planning in colorectal cancer: feedback from survivors & providers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012; doi: 0.1080/07347332.2011.651260.

Haq R, Heus L, Baker NA, Dastur D, Leung FH, Leung E, et al. Designing a multifaceted survivorship care plan to meet the information and communication needs of breast cancer patients and their family physicians: results of a qualitative pilot study. BMC Med Inform Decis. 2013. doi:10.1186/1472-6947-13-76.

Hill-Kayser CE, Vachani CC, Hampshire MK, Di Lullo G, Jacobs LA, Metz JM. Impact of internet-based cancer survivorship care plans on health care and lifestyle behaviors. Cancer. 2013. doi:10.1002/cncr.28286.

Kent EE, Arora NK, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Forsythe LP, Hamilton AS, et al. Health information needs and health-related quality of life in a diverse population of long–term cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:345–52.

Marbach TJ, Griffie J. Patient preference concerning treatment plans, survivorship care plans, education, and support services. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:335–42.

Mayer DK, Gerstel A, Leak AN, Smith SK. Patient and provider preference for survivorship care plans. J Oncol Pract. 2012. doi:10.1200/JOP.2011.000401.

Partridge AH, Norris VW, Blinder VS, Cutter BA, Halpern MT, Malin J, et al. Implementing a breast cancer registry and treatment plan/summary program in clinical practices: a pilot program. Cancer. 2012. doi:10.1002/cncr.27625.

Salz T, Oeffinger KC, Lewis PR, Williams RL, Rhyne RL, Yeazel MW. Primary care providers’ needs and preferences for information about colorectal cancer survivorship care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012; doi: 0.3122/jabfm.2012.05.120083

Sima JL, Perkins SM, Haggstrom DA. Primary care physician perceptions of adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000000061.

Singh-Carlson S, Nguyen SKA, Wong F. Perceptions of survivorship care among south Asian female breast cancer survivors. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:80–9.

Singh-Carlson S, Wong F, Martin L, Nguyen SKA. Breast cancer survivorship and South Asian women: understanding about the follow-up care plan and perspective and preferences for information post treatment. Curr Oncol. 2013;20:63–79.

Smith SL, Singh-Carlson S, Downie L, Payeur N, Wai ES. Survivors of breast cancer: patient perspectives on survivorship care planning. J Cancer Surviv. 2011. doi:10.1007/s11764-011-0185-7.

Smith SL, Wai ES, Alexander C, Singh-Carlson S. Caring for survivors of breast cancer: perspective of the primary care physician. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:e218–26.

Sprague BL, Dittus KL, Pace CM, Dulko D, Pollack LA, Hawkins NA, et al. Patient satisfaction with breast and colorectal cancer survivorship care plans. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:266–72.

Watson EK, Sugden EM, Rose PW. Views of primary care physicians and oncologists on cancer follow-up initiatives in primary care: an online survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2010. doi:10.1007/s11764-010-0117-y.

Wiljer D, Urowitz S, Jones J, Kornblum A, Secord S, Catton P. Exploring the use of survivorship consult in providing survivorship care. Support Care Cancer. 2013. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1760-4.

Reviewers’ Manual, Appendix III. Joanna Briggs Institute. 2014. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/ docs/sumari/ReviewersManual-2014.pdf. Accessed May 13, 2014.

Pluye P, Gagnon MP, Griffiths F, Johnson-Lafleur J. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:529–46.

Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, Macaulay AC, Salsberg J, Jagosh J, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:47–53.

Hannes K, Lockwood C, Pearson A. A comparative analysis of three online appraisal instruments’ ability to assess validity in qualitative research. Qual Health Res. 2010. doi:10.1177/1049732310378656.

Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw R, Miller T, Smith J, Young B, et al. Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. Health Serv Res Policy. 2007. doi:10.1258/135581907779497486.

SUMARI: The Joanna Briggs Institute system for the unified management, assessment and review of information. Joanna Briggs Institute. 2007. http://www.joannabriggs.org/sumari.html. Accessed May 13, 2014.

Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N, TREND The Group. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:361–6.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–7.

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–4.

CONSORT Statement. 2010. http://www.consort-statement.org/downloads/consort-statement. Accessed April 8, 2014.

Armstrong R, Waters E, Doyle J. Chapter 21: reviews in health promotion and public health. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1, The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed April 8, 2104.

De Padova S, Rosti G, Scarpi E, Salvioni R, Amadori D, De Giorgi U. Expectations of survivors, caregivers and healthcare providers for testicular cancer survivorship and quality of life. Tumori. 2011;97:367–73.

Given BA, Sherwood P, Given CW. Support for caregivers of cancer patients: transition after active treatment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0611.

Dolce MC. The internet as a source of health information: experiences of cancer survivors and caregivers with healthcare providers. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011. doi:10.1188/11.ONF.353-359.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mary Beth Happ, PhD, RN, FGSA, FAAN, Janine Overcash, PhD, GNP-BC, and Beverly S. Reigle, PhD, RN, for reading and providing feedback on drafts of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Klemanski, D.L., Browning, K.K. & Kue, J. Survivorship care plan preferences of cancer survivors and health care providers: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv 10, 71–86 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0452-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-015-0452-0