Abstract

We report the successful surgical treatment of aortic regurgitation in a 27-year-old woman with Turner syndrome (TS) who was admitted with exacerbation of dyspnea on exertion. Echocardiography showed a bicuspid aortic valve with severe aortic regurgitation and computed tomography showed dilatation of the ascending aorta and aortic root. Due to the patient’s low body surface area (due to TS), standard determination of aortic size was not possible; therefore, we used the reference curves of aortic diameters in children. Because of the possibility of fatal ascending aortic dissection and rupture, we performed concomitant aortic root remodeling and aortic valve repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patients with Turner syndrome (TS) frequently have a bicuspid aortic valve and TS is considered to be a risk for aortic dilation or dissection, similar to Marfan syndrome. Nearly all individuals with TS have a short stature, similar to children [1]. Because there is no aortic diameter-based surgical criterion for aortic replacement in patients with TS, the surgical timing and procedures must be carefully considered. We report a case of successful ascending aortic replacement and aortic root remodeling with repair of a bicuspid aortic valve in a patient with TS, performed using the reference curves of aortic diameters in children [2].

Case report

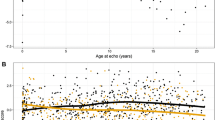

A 27-year-old woman with TS, who has been followed up as an outpatient, since she was 16 years old, admitted to our hospital with dyspnea on exertion. Her body surface area (BSA) was 1.15 m2. Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed severe aortic regurgitation with a bicuspid aortic valve; diastolic and systolic dimensions of 49 and 36 mm, respectively; and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 55%. The right coronary and non-coronary cusps were fused. Aortic regurgitation was caused by prolapse of the left coronary cusp. The maximum diameters of the aortic root and the ascending aorta were 33.5 and 28.5 mm, respectively, and they were normal sized for an adult. However, the aortic root seemed relatively dilated compared with the ascending aorta (Fig. 1a, b). According to the index of aortic diameters by BSA for children, both her aortic root and ascending aorta were 1.5 times larger than normal [2].

Preoperative computed tomography showing a dilated aortic root in the coronal plane and b in the axial plane. Intraoperative pictures showing c fused right coronary and non-coronary cusps, with slight thickening and d central plication. Histopathological examination showing e limited myxoid degeneration (alcian blue/periodic acid–Schiff stains ×100)

Because the patient, due to TS, has the possibility of complications from Type A dissection in the near future, we decided to perform an ascending aortic replacement and aortic root remodeling with aortic valve (AV) repair.

A median sternotomy was performed. Cardiopulmonary bypass was established via cannulation of the ascending aorta with bicaval venous return. Transection of the ascending aorta revealed a bicuspid aortic valve consisting of fused, noncalcified, right coronary, and non-coronary cusps. The geometric height of the non-fused, left coronary cusp was 21 mm and that of the basal ring was 24 mm. We felt that it would be possible to perform aortic root remodeling and AV repair using the anatomical measurements of her aortic root and valve [3]. The aortic root was exfoliated to the level of the basal ring, so that external annuloplasty with a prosthetic graft ring could be performed. After replacing the ascending aorta with a 22-mm prosthetic graft, five threads with pledgeted are placed from the inside out circumferentially in the subvalvular plane. Three sutures are positioned 2 mm below the nadir of each cusp and two are placed at the base of the interleaflet triangles between the non- and left coronary sinuses and between the left and right coronary sinuses. A sixth suture is passed from externally at the level of the interleaflet triangle between the right and non-coronary sinus to limit the risk of membranous septum. The six anchoring stitches are passed through the inner aspect of the 5-mm prosthetic graft ring. The ring is then descended around the remodeled aortic root. The stitches are tied to secure the ring in subvalvular position. We tailored a 24-mm Vascutek® Gelweave Valsalva™ Graft (Terumo Medical Corp., Somerset, NJ, USA) into two symmetrical neosinuses to adjust for the asymmetrical native commissures. The prolapsed fused cusp (Fig. 1c) was repaired with central plication (Fig. 1d) to adjust the effective height (9 mm) using a Schäfers calliper (Fehling Instruments, Karlstein, Germany). Finally, the bilateral coronary buttons were anastomosed to the Valsalva graft using the Carrel patch technique. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful.

Histopathological examination of the resected aortic wall demonstrated limited myxoid degeneration with no evidence of either fragmentation or separation of the elastic fibers. Alcian blue/periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stains were positive in the areas of myxoid change (Fig. 1e). Cystic medial necrosis, which is often seen in the patient with Marfan syndrome, is called myxoid medial degeneration too.

Discussion

Although a few authors have described the risks of aortic dilation and dissection in patients with TS, there is no surgical criterion with respect to aortic dimension and rate of dilatation for these patients [1]. Patients with TS have two problems in the aorta that have to be taken in consideration. The first is the likelihood of aortic dissection. In a Danish study, the estimated incidence of aortic dissection in patients with TS is 36/100,000 patients per year, and is six times more complicated than in a healthy female population [4]. The majority of dissections in patients with TS occur at the ascending aorta, and young adults aged from 20 to 40 years have a high risk for aortic dissection Type A [4]. The second problem is aortic dilatation. Abnormal dilatation of the aorta, especially at the aortic root into the ascending aorta, is frequently seen in patients with TS [1].

The problem was how to determine the surgical criterion using aortic dimensions. As one of the features of TS is short stature, the surgical criteria for adult aortic diameters would not apply. We diagnosed our patient with aortic root dilatation using the reference curves of aortic diameters in children based on BSA [2]. Matura et al. reported an aortic size index based on the ratio of ascending aortic size to BSA. A dilated ascending aorta, i.e., aortic size index > 2.0 cm/m2, requires close cardiovascular surveillance, and ≥ 2.5 cm/m2 indicates the greatest risk for aortic dissection [5]. In our patient, the aortic root and ascending aorta indices were 2.91 and 2.48 cm/m2, respectively, and had been gradually increasing (Fig. 2). Histopathological examination demonstrated myxoid degeneration, which indicated the risk of aortic dissection or aneurysm rupture in the near future, as demonstrated in Marfan syndrome [6]. Therefore, we considered it to be an appropriate time for the replacement procedures.

Several authors have reported ascending aortic and aortic root replacement in patients with TS. Kin et al. reported using a modified Bentall procedure and total arch replacement for a Stanford type A chronic aortic dissection in a patient with a bicuspid aortic valve [7]. Although the Bentall procedure is standard in aortic root surgery, valve sparing root surgery has become more popular and has achieved good results in recent years [8]. To date, the long-term durability of bicuspid aortic valve repair in patients with TS has not been well established. Since there are a few reports as to whether good hemodynamic function and durability of the bicuspid valve repair is achieved [9], we selected a root remodeling procedure with bicuspid valve repair for our patient.

Conclusion

We successfully performed ascending aortic replacement and aortic root remodeling with bicuspid aortic valve repair in a patient with TS. At present, no evidence-based guidelines exist for a cardiovascular approach in this patient population. Using the reference curves of aortic diameters in children based on BSA might be a useful method for determination of the appropriate time for surgery.

References

Lopez L, Arheart KL, Colan SD, et al. Turner syndrome is an independent risk factor for aortic dilation in the young. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1622–e1627.

Kaiser T, Kellenberger CJ, Albisetti M, Bergsträsser E, Buechel ERV. Normal values for aortic diameters in children and adolescents – assessment in vivo by contrast-enhanced CMR-angiography. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2008;10:56.

Schäfers HJ, Schmied W, Marom G, Aicher D. Cusp height in aortic valves. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;146(2):269–274.

Gravholt CH, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Stochholm K, Hjerrild BE, Ledet T, et al. Clinical and epidemiological description of aortic dissection in Turner’s syndrome. Cardiol Young. 2006;16:430–436.

Matura LA, Ho VB, Rosing DR, Bondy CA. Aortic dilatation and dissection in Turner syndrome. Circulation. 2007;116:1663–1670.

Dermengiu S, Ceausu M, Hostiuc S, Curca GC, Dermengiu D, Turculet C. Spontaneous aortic dissection due to cystic medial degeneration. Report of a sudden death case and literature review. Rom J Leg Med. 2009;17(2):89–96.

Kin H, Okabayashi H, Nakajima T, Takahashi K. Aortic dissection aneurysm with a bicuspid aortic valve in Turner’s syndrome. Surg Today. 2007;37:667–670.

Arimura S, Seki M, Sasaki K, et al. A nationwide survey of aortic valve surgery in Japan: current status of valve preservation in cases with aortic regurgitation. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;65:429–434.

Aicher D, Kunihara T, Issa OA, Brittner B, Gräber S, Schäfers H-J. Valve configuration determines long-term results after repair of the bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation. 2011;123:178–185.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Inno, G., Takahashi, Y., Kato, Y. et al. Aortic root remodeling in a patient with Turner syndrome using the reference curves of aortic diameters in children. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 66, 667–670 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-018-0889-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-018-0889-y