Abstract

This study is a meta-analysis of how pull marketing actions influence the effectiveness of marketing actions employed by multichannel firms. Pull marketing actions are highly adaptable marketing actions designed to make multichannel distribution channel portfolios attractive. Integrating prior multichannel distribution literature, the authors investigate whether marketing actions’ effectiveness depends on pull marketing actions and their configuration with the distribution channel structure and attributes of customer, competition, and product category. The analysis that considers firm, data, and model attributes of the sampled studies reveals that marketing actions’ effectiveness is higher when multichannel firms use digital advertising and price promotions in all distribution channels. Price discrimination across channels does not improve marketing actions’ effectiveness. Furthermore, marketing actions’ effectiveness depends on how digital advertising and price promotions are aligned with channel variety, channel richness, customer experience, market competitiveness, and product purchase infrequency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Multichannel distribution is considered imperative for firms to stay competitive in the marketplace. Distribution channels in a typical multichannel portfolio might include some combination of online websites, mobile websites/apps, physical stores, and catalogs. However, a recent study involving more than 4,000 consumers and practitioners concludes that there is high variation in the performance of multichannel firms (Newman & McClimans, 2019). Other studies suggest that this variation is partly due to differences in marketing actions designed to incentivize purchases in distribution channel portfolios. For instance, surveys of chief marketing officers repeatedly reveal a lack of understanding about how marketing actions implemented across firms’ distribution channel portfolios can entice customers more effectively (Coughlan & Jap, 2016; Kotler, 2012; Moorman, 2017). Considering these studies and surveys, managers are actively engaged in understanding “what marketing actions in distribution channels can effectively enhance multichannel firm performance” (Hanbury, 2020; Maier & Wierenga, 2021; Ailawadi & Farris, 2020). Although there is a substantial base of practitioner and academic research (e.g., Gao & Su, 2017; Kumar & Venkatesan, 2005; Liu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2010), calls to understand the effectiveness of marketing actions in a multichannel distribution context still remain very relevant.

In this regard, the literature on distribution channel management suggests that marketing actions in distribution channels are primarily “pull-based” (Ataman et al., 2010; Bradford & Boyd, 2020). Pull marketing actions described in the multichannel distribution management literature comprise those marketing actions that are adaptable, directly aimed at consumers, and emphasize entire distribution channel portfolios (not selective channels). Pricing, advertising, and product-based actions that are directed at customers comprise pull marketing actions that managers can tactically change as required. These actions such as communicating price promotions in every channel, differentiated pricing across channels, digital advertising to promote every channel, and varying product line and breadth across channels, can be deployed across the distribution channel portfolio. We differentiate pull actions from push actions, which are mostly pricing actions only directed at trade intermediaries and are therefore not meaningful for the entire distribution channel portfolio of multichannel firms (Sardanelli, 2020; Ailawadi & Farris, 2017, 2020). Consequently, to further our understanding of the “effectiveness of marketing actions for multichannel firm performance,” we focus on pull marketing actions that emphasize the distribution channel portfolios of multichannel firms. We also consider the extent to which pull marketing actions can influence marketing action effectiveness in a multichannel firm (hereinafter referred to as MAE).

There does not exist a generalizable answer to our research question in the literature on distribution channels. A literature review (see Table 1) shows that studies selectively investigate pull marketing actions in varied contexts. For example, Chang (2012) focuses on the role of communication, whereas Gallino and Moreno (2014) look at cross-channel shopping features. Meanwhile, Konuş et al. (2008) examine contexts related to customer attributes, Kumar et al. (2019) investigate contexts pertaining to competition, and others capture contexts related to the channel structure such as the presence of physical stores in multichannel portfolios (e.g., Hartung, 2016; Richter & Street, 2018). Such selective assessment of pull marketing actions might also explain why there are some open questions lingering in the literature about the effectiveness of marketing actions in multichannel firms. For example, consider the ongoing debate about whether customers are responsive to digital advertising customized according to expressed preferences (Chen, 2018). Such targeted communication reduces customers’ information search costs, yet it creates distrust and privacy concerns, thereby influencing potential customers’ purchase decisions (Bleier & Eisenbeiss, 2015; Fong, 2012; Goldfarb, 2014). Similarly, although they constitute an integral component of pull actions, price promotions’ effects are mostly short-lived, and their contribution to firm value is sometimes questioned (Srinivasan et al., 2004) and other times validated (Zhang et al., 2020). The literature on multichannel distribution also identifies price discrimination across channels as a key factor that helps firms take advantage of consumers’ heterogeneous price sensitivities (Chu et al., 2007; Kacen, 2003), yet its influence on customers’ unfairness perceptions is also highlighted (Wolk & Ebling, 2010).

Against the backdrop of varied research foci and findings, we take the configuration-theoretic perspective, which in the multichannel domain is considered as a system of business actions configured with the distribution channel structureFootnote 1 and market conditions (Kabadayi et al., 2007; Arnold & Palmatier, 2012; Kauferle & Reinartz, 2015). The configuration perspective helps visualize the controllable or highly adaptable elements of the business (i.e., pull marketing actions) and the less adaptable and often uncontrollable parts of the business environment together (e.g., Vorhies & Morgan, 2003). Any element of the configuration is effective to the extent it is aligned with the other two elements. Thus, if business actions that make distribution channels attractive adapt to the attributes of the distribution channel structure and those of the market, they contribute most to multichannel firm performance (Kabadayi et al., 2007). Although this particular theoretical perspective is considered to provide a holistic description of a multichannel firm, there is considerable uncertainty about how well these configurations work. In the extant empirical multichannel distribution literature, most studies assess either one element (mostly business actions or channel structure, e.g., Li & Kannan, 2014; Fisher et al., 2019; Gu & Kannan, 2021) or two-element configurations of a multichannel firm’s business. Concerning the latter, a majority of studies consider either the alignment of the channel structure with market attributes (e.g., Bell, Gallino, & Moreno, 2018; Akturk et al., 2018) or business actions with the channel structure (e.g., Kushwaha and Shankar, 2013; Zhang & Wedel, 2009). Thus, there is no generalizable understanding of how business actions might work together with both the channel structure and market attributes.

Channel structure and market attributes represent the elements of a multichannel firm’s configuration that are “less” controllable. Market attributes are obviously external to the firm. The channel structure (i.e., elements of the distribution channel such as the choice of channel modes) can be conceptualized as marketing actions that cannot be tactically changed as needed because it involves inter-firm dependencies and a potential for channel conflict, all of which complicate and restrict agile changes (Ailawadi & Farris, 2020). In contrast, business actions such as pull marketing actions are tactical and can be configured based on the needs of the channel structure and market conditions. Yet, a systematic conclusion about such configurations remains to be drawn. Accordingly, we aim to meta-analyze previous multichannel studies on MAE while accounting for study-specific heterogeneity related to data and methodologies. Such a meta-analysis allows making generalizable conclusions about how different pull marketing actions, channel structure, and market conditions might together influence MAE. Our meta-analysis highlights theoretical and empirical relationships that contribute to the flourishing discussion on multichannel distribution (MSI, 2020).

In the meta-analysis, we define MAE as the estimated elasticity of marketing actions that a multichannel firm uses to create customer demand in its distribution channel portfolio. The elasticity is based on firm performance. We include in our definition both topline performance measures such as sales and bottom-line performance measures such as profits. Our meta-analysis consists of 66 unique studies encompassing a wide range of published and unpublished works with 546 distinct observations for MAEs.Footnote 2 After controlling for several study level attributes related to data characteristics, publication type, and the presence of endogeneity/heterogeneity correction, our findings suggest that digital advertising and price promotions across channels contribute more to MAE than price discrimination. Further, digital advertising contributes more to MAE when products are infrequently purchased, customers are experienced, and physical channels are included in the distribution channel portfolio of multichannel firms. Meanwhile, price promotions across channels are more effective for infrequently purchased products, highly competitive markets, and for distribution channel portfolios with a variety of channel modes. We also derive additional insights, e.g., firms that show specific sequences of channel addition are more successful in their marketing actions. Finally, we find that MAE estimates in the distribution literature are sensitive to the metric of firm performance as well as to the use of endogeneity corrections. We acknowledge that our constructs do not represent the entire domain of pull marketing actions, channel structure, and market conditions. Instead, in the spirit of a meta-analysis, our study provides generalizable findings for those representative constructs that are frequently assessed in empirical studies in the distribution channel literature.

Theory and hypotheses

As per configuration theory, a multichannel firm’s performance should depend on how well business actions, the channel structure, and market conditions fit together. Since the channel structure and market conditions are the less adaptable parts of a multichannel firm’s business, it is imperative that business actions be adapted according to the other two elements. This adaptation significantly enhances the value proposition for customers to make them respond favorably to marketing actions (Gatignon, 1993). Business actions are represented by pull marketing actions that are directed at customers to emphasize the attractiveness of every channel in the multichannel distribution portfolio. In particular, as per the summarized typology of a multichannel distribution system suggested by Ailawadi and Farris (2020), pull marketing actions include pricing actions and digital advertising among others. Pricing actions refer to having differential pricing across channels, which we call price discrimination, and the use of price promotions in every channel (Chandon et al., 2000; Van Heerde & Neslin, 2017). Digital advertising deploys display ads, paid search ads, social media ads, retargeted ads, and email marketing,Footnote 3 all of which are designed to direct customers to every distribution channel in a multichannel firm’s portfolio (Fong, 2012; Goldfarb, 2014). Although pull actions can also include product-based actions such as adjusting product line breadth and depth across channels, we are unable to include them in our meta-analysis due to the paucity of empirical studies about product-based pull actions in the literature on multichannel distribution.

The channel structure comprises channel variety and richness. Channel variety represents the number of distribution channel modes (online, mobile, or offline). Each mode provides distinct benefits to customers in their search for products. Whereas offline modes such as physical stores allow a rich hands-on experience with a product, online modes such as websites provide convenience and enable the exploration of entire product lines, and mobile modes offer convenience as well as product customization based on geolocation. Studies confirm that the three modes are sufficiently differentiated in terms of the nature and intensity of customer engagement (Almarashdeh et al., 2019; Cui et al., 2021). Channel richness indicates the extent to which a firm’s channels enable customers to interact with products, and it can considerably enhance product attractiveness (Shankar & Kushwaha, 2021). Thus, channel richness can be reasonably described by the presence of physical stores in a multichannel distribution portfolio because physical stores allow the maximum possible sensory experience with products in the pre-purchase stage. Market conditions represent customer level, competitor level, and product category level attributes. At the customer level, we consider customers’ experience with a multichannel firm regarding either prior purchases or in interactions with the firm’s distribution channels. Such experiences or familiarity is used by firms to understand customer preferences so that pull actions may be aligned accordingly (Kumar, Dalla Pozza, & Ganesh, 2013; Gupta, Lehmann, & Stuart, 2004). At the competitor level, we consider market competitiveness. Pull actions are critical to differentiate between competitors especially when firms react quickly and aggressively to each other’s strategies, a characteristic of highly competitive markets (Fan & Yang, 2020; Barney, 2014). At the level of product category, we consider whether the products are infrequently or frequently purchased. This correlates with the lack of habitual preference formation, which is considered by firms to predict how customers might respond to pull actions (e.g., Liu-Thompkins & Tam, 2013). The infrequency of purchase in the product category is interpreted as a market condition because it describes a fundamental attribute of the product market and cannot be altered by a firm unless it ceases to operate in the market.

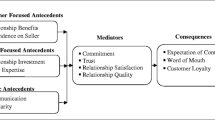

In the following subsection, we discuss how pull marketing actions on their own and when configured with the channel structure and market conditions may influence MAE and then develop formal hypotheses (Fig. 1).

Price discrimination

Differential pricing across channels might help firms take advantage of the price sensitivities of different customer segments (Chu et al., 2007). Moreover, studies show that price discrimination is effective in very specific cases such as separated customer segments in the case of underdeveloped markets (Wolk & Ebling, 2010) and pricing in line with segment-specific norm perceptions (Choi & Mattila, 2009). In general multichannel firms are however motivated to avoid price discrimination across their distribution channels (Flores & Sun, 2014; Zhang et al., 2010). This is because customers typically have access to multiple distribution channels’ price information and therefore may perceive unfairness if they observe a price asymmetry across distribution channels (Choi & Mattila, 2009). Customers’ price evaluations influence how they assess the overall customer experience. Perceived benefits decrease when they feel that the pricing is unfair (Fassnacht & Unterhuber, 2016), thereby negatively affecting customers’ engagement with the firm via its varied distribution channels. As customer engagement is a key driver of purchase incidences (Verhoef et al., 2010), we expect that the presence of price discrimination likely discourages customers from purchasing from the firm regardless of the channel. Thus, effectiveness of a multichannel firm’s marketing actions likely reduces to the extent it engages in price discrimination across channels. In terms of MAE,

H1

The presence of price discrimination is associated with a decrease in the effectiveness of marketing actions of a multichannel firm (MAE).

Price promotions across channels

Firms often use price promotions to incentivize purchases (Shi et al., 2005). Price promotions improve customer experience by adding short-term utilitarian (i.e., value for money) and hedonic (i.e., the joy of finding deals and learning about promoted products) benefits (Aydinli et al., 2014; Chandon et al., 2000). Against this backdrop, we predict that price promotions, when offered in all channels, serve as a tool for multichannel firms to enhance overall customer experience. It generates short-term utilitarian and hedonic benefits of interacting with a firm via its varied distribution channels. Such benefits might evoke instant purchase intentions regardless of the channel through which customers interact with the firm. Price promotion’s benefits might also increase anticipations of promotions such that customers keep tracking the firms’ offerings on multiple distribution channels, which may translate to more purchase incidences over time (e.g., Zhang et al., 2019). In sum, we infer that price promotions incentivize potential customers to interact with a multichannel firm via its distribution channels over prolonged periods of time. Such continual interactions might increase customer engagement with the firms’ varied distribution channels, thereby increasing the likelihood of purchases. Thus, the effectiveness of marketing actions likely increases in the presence of price promotions across all channels of a multichannel firm. In terms of MAE,

H2

The presence of price promotions across all channels is associated with an increase in the effectiveness of marketing actions of a multichannel firm (MAE).

Digital advertising

We consider digital advertising as a multichannel strategy for the following reason. In the literature on multichannel distribution, we note that when firms deploy digital advertising, they do not promote some specific channels over others. Instead, most studies assess digital advertising that encourages customers to visit every distribution channel. Some forms of digital advertising such as display ads are implemented within all distribution channels as well. Further, whether digital advertising emphasizes a channel and/or is implemented in one channel of a multichannel firm, the effects always spill over to all other channels (e.g., Dinner et al., 2014; Ansari et al., 2008), which points to the multichannel nature of digital advertising.

As argued above, in our meta-analysis, digital advertising is a form of targeted multichannel communication. Multichannel firms might target different segments of customers and send messages to all such segments emphasizing the personalized benefits of shopping within a multichannel distribution portfolio (Tinnila et al., 2005). Targeted communication also allows multichannel firms to repeatedly inform customers of the benefits of engaging with a multichannel distribution portfolio. Such targeting on the one hand might risk consumer annoyance and negative feedback and on the other hand helps firms gain eyeballs and brand awareness, which are critical precursors of eventual conversions (Manchanda et al., 2006). In addition, the reach of digital advertising allows customized messaging to numerous segments of potential customers (Bala & Verma, 2018). The scale of targeted messaging not only increases the volume of potential customers engaging with preferred channels but also enables customer attention to spill over to all other channels offered by the multichannel firm (Desai, 2019), which in turn raises the likelihood of conversions in every channel (Honka et al., 2017). Thus, we propose that the effectiveness of marketing actions of a multichannel firm should increase in the presence of digital advertising. In terms of MAE,

H3

The presence of digital advertising is associated with an increase in the effectiveness of marketing actions of a multichannel firm (MAE).

Configuration of pull marketing actions with the channel structure (variety and richness)

With channel variety

Channel variety refers to the number of different modes of distribution such as offline, online, and mobile offered by a multichannel firm. We assess the advantages of channel variety for each of the three pull marketing actions. First, when multichannel firms engage in price discrimination, customers are sometimes able to rationalize price differences based on their layman understanding of the cost structures of some specific channels (e.g., physical stores are more expensive to operate; Fassnacht & Unterhuber, 2016). Such rationalization might fail as the number of distinct channels with different pricing increases partly due to a limited understanding of how different channels work (especially online and mobile channels) and partly due to the increasing confusion about quality signals in different channels (Neslin et al., 2006; Neslin & Shankar, 2009). With different pricing in all varieties of channels, rationalization fails and consequently allows perceptions of unfairness to increase, which adds to the already discussed disadvantages of price discrimination in H1. Second, in terms of price promotions, if promotions are offered in varied channels, the scale of varied customers who are incentivized to interact with the firm increases. Further, due to the universal availability of price promotions, customers will be less motivated to switch between channels. Thus, channels will likely not cannibalize each other, which only complements the firm’s intention of increasing reach by increasing channel variety. Finally, in terms of digital advertising, studies show that targeted communication attracts customers to the different channel modes based on channel preferences (e.g., Ansari et al., 2008). As digital advertising draws potential customers to every channel, it complements channel variety to increase the total number of potential customers that interact with the firm. As digital advertising is also known to cause positive spillovers in the channel portfolio, the scale of spillovers should increase with the increase in channel variety. As a result, digital advertising complements the firm’s motivation to reach different customers through more varied channels, thereby increasing the probability of purchases in every channel.

Overall, we propose that price discrimination does not align well with higher channel variety, but price promotions across channels and digital advertising align well with higher channel variety. In terms of MAE,

H4

With increasing channel variety, (a) the negative association between price discrimination and MAE will increase, (b) the positive association between the presence of price promotions across channels and MAE will increase, and (c) the positive association between the presence of digital advertising and MAE will increase.

With channel richness

As the richness of the channel structure refers to the extent to which customers can interact with products before purchase, we consider the presence of physical stores in the distribution channel portfolio as indicating channel richness. We assess the advantages of having a physical store for each of the three pull marketing actions one at a time.

First, in terms of price discrimination, we argue that customers can implicitly understand differential pricing as far as physical stores are concerned (Hartung, 2016; Richter & Street, 2018). Associated expenses of inventory, personnel, and infrastructure management have been touted as the most common reasons for store closings in the last decade (Briedis et al., 2020). With regard to other channels, using such simplistic logic is not meaningful, and more financially complex logic related to tax structures and technological infrastructure may apply, which most customers may not comprehend (Mohammed, 2017). Hence, for a customer, differential pricing may be easier to reconcile and be assessed as less unfair in the presence of physical stores than in their absence. Consequently, differential pricing aligns better with the presence of physical stores (versus in their absence) in the channel portfolio. Second, in terms of price promotions, the alignment with having physical stores might not be meaningful because simultaneous price promotions can make every channel equally attractive. Thus, price promotion complements every channel and not just physical stores. Finally, in terms of digital advertising, it may be advantageous to have a physical store. Although such targeted communication can attract different customers to different channels, having physical stores might allow greater spillover. For instance, due to geolocation, mobile app ads can indicate the presence of physical stores at the right moment. This motivates customers on mobile apps to visit a store, thereby incentivizing conversion due to the support and advantages that salespeople and physical store ambience provide (Zhang et al., 2021). Further, multichannel firms strategically target ads at customers who engage in webrooming (e.g., online browsing without filling a cart, or abandoning a cart) to emphasize nearby physical stores in which customers are very likely to make purchases (Forbes, 2016).Footnote 4 Thus, having a physical store (versus its lack) incrementally adds to the benefits of digital advertising of a multichannel firm.

Overall, we propose that having a physical store in the distribution channel portfolio aligns well with price discrimination and digital advertising, whereas its alignment with price promotions across channels does not matter. In terms of MAE,

H5

With the presence of physical stores in the distribution channel portfolio, (a) the negative association between the presence of price discrimination and MAE will decrease, and (b) the positive association between the presence of digital advertising and MAE will increase.

Configuration of pull marketing actions with customer experience

Experienced customers who are familiar with a multichannel firm (either due to prior purchase or engagement with the firm’s offerings via its distribution channels) have a relatively clear understanding of the firm’s attributes and product offerings (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987; Johnson & Russo, 1984). In a multichannel context, studies show that experienced customers base their purchase decisions on their sufficient contextual knowledge and as a result face very low uncertainty in their purchase journey (e.g., Cambra-Fierro et al., 2020; Herziger & Hoelzl, 2017). Multichannel studies have consistently shown that experienced customers due to their low uncertainty in the purchase journey perceive less risk in responding to the marketing actions of firms (Gensler et al., 2012; Kumar & Venkatesan, 2005). These experienced customers are more likely to interact with different channels in a firm’s distribution portfolio if their engagement is incentivized by typical pull marketing actions such as digital advertising and pricing (Montaguti et al., 2016; Neslin et al., 2014). Compared with such experienced customers, those who do not have as much experience or familiarity with a firm show more uncertainty throughout their purchase journey, have less trust in marketing-related information, and therefore are slower and more tentative in responding to pull marketing actions (Cambra-Fierro et al., 2020). As a result, less experienced customers are less easily swayed by pull marketing actions (Herziger & Hoelzl, 2017; Valentini et al., 2011). Thus, as increased customer experience correlates with increased sensitivity to pull marketing actions in multichannel settings, more (versus less) experienced customers may be more easily incentivized with price promotions and digital advertising to make purchase decisions. If customers become more sensitive to a firm’s pull marketing actions due to their experience, they are more likely to consider the firm’s price discrimination across channels as an important factor in making their purchase decisions. As price discrimination is generally perceived as an unfair practice that adversely affects purchase decisions (as we propose in H1), more (versus less) experienced customers who care more about price discrimination are likely to be more adversely affected by it.

In summary, we propose that more (versus less) experienced customers align better with digital advertising and price promotions across channels but worse with price discrimination. In terms of MAE,

H6

For more experienced versus less experienced customers, (a) the negative association between the presence of price discrimination and MAE increases, (b) the positive association between the presence of price promotions across channels and MAE will increase, and (c) the positive association between the presence of digital advertising and MAE will increase.

Configuration of pull marketing actions with market competitiveness

Competitive markets are characterized by a high heterogeneity of product choices (Fan & Yang, 2020). Due to the sheer variety of product choices in highly competitive (relative to less competitive) markets, the extent of customer loyalty in the former is lower as well (McMullan & Gilmore, 2008). In environments characterized by less customer loyalty, customer switching costs are low, and customers are more accepting of and therefore more responsive to firms’ attempts to differentiate themselves. As a result, as market competitiveness increases, firms tend to rely more on pull marketing actions to distinguish themselves (Gans, 2002). Research by Villanueva et al. (2007) echoes the above finding by showing that a firm in a highly competitive setting might achieve better returns by focusing on period-by-period advertising and pricing tactics rather than trying to build customer loyalty through strategies such as extended relationship management programs. This logic should play out in a multichannel setting as well such that customers respond more favorably to differentiating pull marketing actions of multichannel firms as market competitiveness increases. Increasing favorability of customer responses implies that differentiating actions such as digital advertising and price promotions are likely to make a multichannel firm’s offerings more attractive in competitive markets. If customers deem a multichannel firm’s pull marketing actions as reasonable tactics aimed at differentiation in highly competitive markets, they are more likely to be accepting of such practices (Maxwell & Garbarino, 2010). Thus, even though price discrimination across channels is generally considered an unfair practice (as we propose in H1), in highly competitive markets, such perceptions of unfairness might be less salient as it is considered a reasonable tactic by which a firm differentiates itself (e.g., Flores & Sun, 2014).

In summary, we propose that more competitive versus less competitive markets align better with digital advertising, price promotions across channels, and price discrimination. In terms of MAE,

H7

As market competitiveness increases, (a) the negative association between the presence of price discrimination and MAE decreases, (b) the positive association between the presence of price promotions across channels and MAE will increase, and (c) the positive association between the presence of digital advertising and MAE will increase.

Configuration of pull marketing actions with product purchase infrequency

We classified products into two categories: frequently purchased goods (FPGs) – those that customers habitually purchase (e.g., office supplies, food, personal hygiene products, etc.) and infrequently purchased goods (IFPGs)—those not purchased habitually (e.g., electronics, wine, apparels, etc.). As customers purchase FPGs frequently unlike IFPGs (Rundle‐Thiele and Bennett 2001; Young et al., 2010), the purchases of FPGs tend to be characterized by convenience and habit both in terms of the product brand as well as the channels of purchase (Dick & Basu, 1994; Peter et al., 1999; Phau & Poon, 2000). In contrast for IFPGs, due to the relative rarity of purchase experiences (Miller et al., 2010), customers are less likely to have established preferences (e.g., Kiang et al., 2000). Because of the less-established preferences of IFPGs (versus FPGs), customers of IFPGs tend to be more receptive to pull marketing actions aimed at encouraging preference switching, such as digital advertising and price promotions. Thus, the effectiveness of digital advertising and price promotions of multichannel firms might be higher for customers of IFPGs than FPGs. Unlike digital advertising and price promotions that customers of IFPGs (relative to FPGs) are more receptive to, price discrimination might work differently. Customers of FPGs, due to their established preferences, consider themselves loyal customers and therefore expect to be rewarded with the best prices in the channels of their choice (e.g., Homburg et al., 2019). With price discrimination, customers of FPGs feel disgruntled if the best prices are not being offered in their preferred channels, which causes dissatisfaction and perceptions of unfairness. In comparison, customers of IFPGs might be less expectant of being rewarded with best prices and therefore might be less sensitive and react less negatively to price discrimination. In all, in terms of MAE,

H8

For customers of IFPGs relative to FPGs, (a) the negative association between the presence of price discrimination and MAE decreases, (b) the positive association between the presence of price promotions across channels and MAE increases, and (c) the positive association between the presence of digital advertising and MAE increases.

Methodology

Data collection and coding strategies

For a comprehensive coverage of multichannel distribution studies, we conducted a literature search using the following steps. First, we identified published studies on multichannel distribution through keyword search in all major electronic databases, including Web of Science, ABI/INFORM Global, Scopus, EBSCO, Emerald, Business Source Complete, Science Direct, and Google Scholar. The keywords include “distribution channel,” “multichannel marketing,” “multichannel retailing,” “multichannel strategy,” “multichannel shopping,” “shopping channel preference,” “online/offline shopping,” “channel choice,” and “channel addition,” as well as their combinations with terms such as “business performance,” “profitability,” and “purchase,” etc. Second, independent of the first step, we scrutinized each issue of every major marketing and business management journal based on the abovementioned keywords.Footnote 5 Third, to address the “file-drawer” problem, we used the ProQuest database to search for dissertations with the above keywords. We also contacted scholars who actively work in this field, requesting for their working papers relevant to the topic, and posted announcements on the academic portal (i.e., ELMAR) to seek any other unpublished studies in this area. Finally, we scanned the bibliography lists of all published and unpublished studies to identify any articles that we might have missed in the previous steps.

Inclusion criteria

We applied the following inclusion criteria to finalize the sample. First, consistent with prior meta-analyses in the marketing discipline (Assmus et al., 1984; Bijmolt et al., 2005; Sethuraman et al., 2011), all sampled papers on multichannel distribution must either directly report the MAE estimates based on econometric models or contain regression coefficients that we can derive and convert to MAEs. Studies solely based on experimental studies are therefore excluded (You et al., 2015). Second, the directly reported or derived MAE must capture the effectiveness of a marketing actionFootnote 6 with regard to the firm’s performance, not channel-specific performance. We include varied types of firm performance in our sample. Sales-related effectiveness includes $ sales, survey measures of purchase intentions for a firm/brand, and product purchase incidence for a firm/brand. Profit-related effectiveness includes $ profit, $ return on assets, return on equity, and survey measures of overall firm performance. With the application of these criteria, the initial sample contains 72 studies associated with 100 independent samples and 572 MAE observations from 1999 to 2021. However, we recognize that our theoretical framework is more applicable to B2C firms than B2B firms. In B2B firms, several components of our configuration are irrelevant such as the presence of physical stores and the frequency of product purchase. Further, pull marketing components such as salespeople are critical to B2B and are not captured in our framework. The lack of similarity between multichannel marketing actions in B2C and B2B firms is reflected in our dataset such that more than 90% of studies and more than 90% of independent samples comprise B2C firms. Thus, we retained only B2C samples for our analysis. As a result, our final dataset contains 66 studies and 91 independent samples as well as 546 MAE observations (see Table WA1).

MAE derivation and reweighting

If an MAE was estimated based on a log–log regression equation, it was interpreted as “a certain percentage change in the value of an independent variable is likely to lead to a certain percentage of change in firm performance”. The magnitudes of such MAEs are comparable across studies. Thus, we directly recorded the MAE magnitudes in our database with no further derivation. If an MAE is estimated in a log-level or level-log regression equation, we applied the formula provided by Gemmill et al. (2007) to further convert it and make the finally derived MAE comparable across different samples and studies. In the end, 81 MAEs from 18 independent samples were converted (See Table WA2).

Another concern with the collected MAEs is the overrepresentation problem. Multiple MAEs from a single data sample that represent the same independent-and-dependent variable relationship are reported in one study.Footnote 7 We include all such MAEs if they meet our inclusion criteria. This ensures that our meta-analysis reflects the landscape of research in this discipline with little subjective intervention from us. Notwithstanding, it results in a large number of observations concentrated around certain studies that reported many MAEs. If left unattended, such an issue could bias our modeling estimation due to the overrepresentation of studies reporting a large number of MAEs. To prevent our meta-analysis results from being skewed due to overrepresentation, we reweighed each MAE by multiplying \(1/\) total number of reported MAEs based on the same data sample for the same independent-and-dependent variable relationship (Eisend, 2014; Roschk & Hosseinpour, 2020). For a more detailed description of the reweighting procedure and formula, please refer to the Web Appendix A.

Coding scheme and measurement of the independent and moderating variables

We report the detailed coding schemes of every pull marketing action, channel variety, channel richness, market competitiveness, customer experience, and product purchase infrequency in Table 2.

Measurement of control variables: factors related to firm, data, time, and method

We included a list of control variables as suggested by prior meta-analytical studies. We describe the reasons for including them as control variables here. The detailed measures are discussed in Table 2.

Firm

The firms represented in multichannel studies show variation in the sequence with which new channels were added in the distribution channel portfolio. Forty-seven independent samples reported the sequence of a new channel addition adopted by a multichannel firm (e.g., first offline channel, then website followed by mobile). The remaining 44 independent samples did not disclose such channel sequence information. Although the sequence of channel addition is potentially a channel structure variable that could moderate the effects of pull marketing, due to large missing values for most sequences, we are only able to consider the main effects of some sequences of new channel addition (i.e., physical stores followed by website, website followed by physical stores, and physical stores plus website followed by mobile) and unable to include any interactions with these sequences. Thus, the sequence of channel addition only serves as a control for this analysis. We also control for any indication of cross-channel seamlessness that offers customers the ability to browse, purchase, and process product returns across any channel in the portfolio. This variable indicates the underlying firm ability to manage complex processes, which might help MAE as well.Footnote 8

Data

With respect to publication status, 18 independent samples are unpublished papers including dissertations, conference proceedings, and working papers associated with 109 MAE observations. In addition, 29 independent samples were published in premier journals recognized by the Financial Times, reporting 189 MAEs. Following the practice of prior meta-analytical studies in our field (e.g., Grewal et al., 2018; Schmidt & Bijmolt, 2020), we set fixed-effect variables for both unpublished work and premier journals to control for their potential influence on the empirical results. Finally, with respect to data attributes, we also recognize that the data type of the studies possibly biases the direction of the MAE estimates. The general conclusion among meta-analytical studies in the marketing literature is that the nature of the data type (e.g., primary vs. archival data) might bias empirical results (e.g., Edeling & Fischer, 2016), and therefore we control for the type of the data included in the study.

Time

As our data ranges from 1999 to 2021, we need to control for technological evolution as reflected by the increasing trend of online and mobile channels over time. It is possible that multichannel firms learnt to be more effective with their marketing actions with such technological evolution. Thus, we included a continuous variable labeled “e-sales” that indicates ecommerce (includes mobile and online) volume over the years in the United States reported by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Method

Numerous meta-analytical studies suggest that the accommodation of endogeneity and observation heterogeneity in the model might affect the elasticity estimates of the focal variable (Bijmolt et al., 2005; Sethuraman et al., 2011; You et al., 2015). Thus, we control for these factors in our empirical analysis as well.

Model estimation and procedure

Consistent with prior meta-analytical studies (Palmatier et al., 2006; You et al., 2015), we first performed a univariate analysis to examine the mean and distribution of the reported MAEs. We then estimated the impact of our proposed factors on MAEs. All sampled MAE data in our study may be potentially subject to various measurements or estimation heterogeneities arising from their original studies. Studies vary in their MAE estimation techniques, and such heterogeneities may result in biases in coefficient estimation, which cannot be treated as part of random sampling error. A typical meta-analytic regression process based on the OLS method is inefficient in handling such a nested or hierarchical structure of the MAEs (Denson & Seltzer, 2011; Krasnikov & Jayachandran, 2008; You et al., 2015). Recognizing the limitations with OLS, we employed a hierarchical linear model (HLM) to evaluate between-study variance while controlling for measurement biases due to variations within each individual study. The model is estimated via the maximum likelihood method to acquire robust, efficient, and consistent results (Bijmolt et al., 2005; Hox et al., 2010; Troy et al., 2008):

At level 1, \({MAE}_{ij}\) denotes the ith elasticity estimate from study j. \({\alpha }_{0j}\) is the intercept. \({\alpha }_{1j}\) is a vector of the coefficients measuring the impacts of all the factors \({X}_{ij}\) of our interest including the interaction terms. \({\varepsilon }_{ij}\) denotes the error term. At level 2, we absorb the effect of study characteristics on the slopes evaluated at level 1. Therefore, we have \({\gamma }_{10}\) estimated as the overall coefficient across all selected studies and \({\mu }_{1j}\) as the study-level residual error term.

In this meta-analysis, our goal is to assess how the effectiveness of a multichannel firm’s marketing actions is associated with the configuration of pull marketing actions with both the channel structure and market factors. We set up two models, with Model 1 dealing with the main effects of our interest only and Model 2 evaluating both the main effects and the interactions.

Between-study variance check

Prior to the HLM estimation, we first calculated the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for MAEs reported in our sampled studies. Both metrics evaluate the ratio of between-study and overall variances (Snijders & Bosker, 1994). The within-study variance for the MAEs is \(0.028\) (\(p<.001\)), and the between-studies variance is \(0.075\) (\(p<.001\)). The ratio of between-studies variance component to the total variance is 0 \(.72\)(\(0.075/[0.075+0.028]\)). To account for this 72% of the variance that arises between studies, we use HLM in this study (McGraw & Wong, 1996).

Multicollinearity check

We also conducted a bivariate correlation analysis across all variables of interest (see Table WA3). In this case, if two variables are highly correlated (greater than 0.7), it can lead to multicollinearity. In our sample, all correlation coefficients are smaller than 0.5. The variance inflation scores (VIF) of all included variables in our final model range from 1.28 to 2.68. Both metrics lead us to rule out the multicollinearity concerns (see: You et al., 2015).

Publication bias check

By definition, publication bias suggests that the significance, magnitude, and/or direction of a coefficient estimate (in our context MAE) may lead to the decision of publication or not (Rothstein et al., 2005). Thus, we tested whether such a potential publication bias may result in an invalid estimation of our HLM model results. We first used the trim and fill approach based on Duval and Tweedie (2000). The re-adjusted mean MAE is 0.02, smaller than the actual 0.05. It suggests that the reported MAEs based on our sampled studies might be biased and skewed toward greater values. Next, we calculated the fail-safe N based on the overall dataset. The result is 514, which implies we will need at least another 514 MAE estimates to reverse our modeling results. The large fail-safe Ns indicate that the publication bias identified in the trim and fill process may not be a serious concern.

Results and discussion

Univariate analysis of the MAE

Our final dataset consists of 546 MAEs extracted from 66 studies, associated with 91 independent samples. Figure WA1 presents a histogram of the distribution frequencies of all these MAEs. The mean MAE is 0.05 (standard deviation = 0.27). The total number of studies reporting negative MAEs is 37. Based on Figure WA1, there seems to be a large variance with respect to the distribution of all 546 MAEs of these studies, which might be due to the study-level heterogeneity. Using the HLM model, we are able to examine the impact of each of our interested variables while accommodating within-study variances (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002).

Results of tests of hypotheses

We present the main effect and full model results (i.e., the first two columns) in Table 3. For the sake of brevity, only the results based on the full model (i.e., the second column) are discussed below. We do not find support for H1, so there is a lack of association between the presence of price discrimination across channels and MAE (\(\beta =-.13; p>.10)\). H2 suggesting a positive association between price promotions across channels and MAE is supported (\(\beta =1.03; p< .01)\). In line with H3, we find a positive association between digital advertising and MAE (\(\beta =1.38;p< .01\)).

In terms of the configuration of pull marketing actions with the channel structure, we find the following results. Channel variety is only important for price promotions across channels (\(\beta =.29; p< .01\)), and not for price discrimination or digital advertising. Thus, only H4b is supported. This set of results suggests that channel variety (i.e., the number of channel modes) and price promotions complement each other as the former directly expands the number of contact points with customers and the latter directly incentivizes purchase at every contact point. Digital advertising and price discrimination might make some channels more attractive to customers, given the targeted nature of advertising and the prices differences between channels respectively. Thus, unlike price promotions, these pull actions do not make all channels equally attractive and therefore might not be able to complement the expansion of customer contact points attributed to channel variety.

We also find that channel richness or the presence of physical stores only complements digital advertising as per H5b (\(\beta =.18; p< .05\)) and not price promotion or price discrimination. It is possible that we identify effects only with digital advertising as this pull action being targeted in nature directly encourages spillovers across channels (especially persuading webrooming or non-purchasing customers using online and mobile channels to complete purchases in nearby physical stores; Forbes, 2016). Such spillovers are not likely with price promotions because these are available in every channel and do not incentivize movement across channels. Price discrimination might encourage spillovers to the extent customers want to migrate to and from physical stores in search of better prices. However, the non-significant effect suggests that price discrimination is likely cannibalizing sales from channels in the migration process rather than incentivizing non-purchasing customers in one channel to make purchases in another channel (which digital advertising achieves in contrast).

In terms of the configuration of pull marketing actions with customer experience, we note that only digital advertising works well with customers who have experience with the firm (\(\beta =.07; p< .01\)), as we proposed in H6c. We do not find significant interactions with price discrimination or price promotions. Regarding the configuration of pull marketing actions with market competitiveness, we observe that only the presence of price promotions across channels helps in highly competitive markets (\(\beta =.04; p< .05\)), as we proposed in H7b. We do not find significant interactions with price discrimination or digital advertising. In terms of the configuration of pull marketing actions with product purchase infrequency, we find support for both H8b and H8c, i.e., both the presence of price promotions across channels (\(\beta =.27; p< .05)\) and digital advertising (\(\beta =.12;p< .01\)) work better with infrequently purchased products instead of frequently purchased products. We do not find a significant interaction with price discrimination.

Other meaningful results

Although the channel structure represents a less adaptable marketing action of the multichannel distribution system, we report some main effect results of channel structure that are meaningful for MAE. Channel variety improves customers’ responsiveness to marketing actions in aggregate (\(\beta =.07; p< .05\)), but the mere presence of physical stores (i.e., channel richness) is unhelpful for such responsiveness (\(\beta =-.13; p< .05\)). This latter result combined with some of the interactions reported in the previous section suggests that having physical stores is unhelpful for multichannel firms unless they can use digital advertising to emphasize such stores and encourage channel spillovers. We also find evidence that multichannel firms that initially had physical stores and then added online channels are more successful at enticing customers with marketing actions (\(\beta =.29; p< .01)\) than firms with other sequences of channel addition. This implies that legacy firms that evolved into multichannel firms by adding digital channels are able to take better advantage of marketing actions than digital native firms. In terms of data, we see that MAE estimates are not biased by the type of data (primary vs. archival,\(p>.10\)). Concerning methodology, we note that although accounting for observation heterogeneity (e.g., fixed effects and random effects of observations) does not change MAE estimates, studies that account for endogenous regressors show significantly lower MAE estimates than those that do not (\(\beta =-.26; p< .05)\).

Sensitivity of results to firm performance type

We find that most studies in our data include sales-related MAE elasticities (i.e., 51 studies and 74 independent samples). However, there are also studies using overall performance measures such as profit elasticities (15 studies and 17 independent samples). While we are not specific about the metric of MAE in our theoretical arguments, most of our arguments focus on whether pull marketing actions influence customer’s purchase decisions in a multichannel context. Therefore, our arguments and hypotheses might be more meaningful for top-line performance that only looks at purchase incidence and ignores the cost side of performance. The above logic suggests that we should investigate whether the results are sensitive to firm performance type. Thus, we re-estimate our model by including interactions of our three pull marketing actions with a performance-type dummy variable (1 if MAE is sales-related elasticities and 0 otherwise). We provide the results in the 3rd column of Table 3. We find that both the positive association between price promotions across channels and MAE \(\left(\beta =.70; p< .05\right)\) and the negative association between price discrimination and MAE \(\left(\beta =-.50; p< .01\right)\) are higher with sales-related elasticities than with profit-related elasticities. In contrast, the positive association between digital advertising and MAE is less pronounced with sales-related elasticities than with profit-related elasticities \(\left(\beta =-.44; p< .05\right).\)

Discussion, contribution, and future research

Whether in academia or industry, the effect of marketing actions across distribution channels within a multichannel portfolio is critically debated. In this regard, a meta-analysis is an appropriate method for drawing generalizable conclusions from a systematic review of a body of literature. We contribute to the many open debates about marketing action effectiveness in the multichannel distribution literature. Specifically, we provide an understanding of how pull marketing actions related to digital advertising and pricing should be effectively configured with other less adaptable elements of a multichannel firm’s distribution system, i.e., the distribution channel structure and market factors.

Implications for academic research

The literature on multichannel distribution has primarily addressed the pairwise configurations of pull marketing actions with either the distribution channel structure or market attributes (i.e., customer, competitor or product category). Our meta-analysis reveals that the multi-element configuration of pull marketing actions with distribution channel structure, customer attributes, competitor attributes, and product category attributes are all vital for the effectiveness of marketing actions in multichannel firms. Further, it is important to understand the above multi-element configuration with respect to specific pull marketing actions. For instance, price promotions across distribution channels align with other elements very differently than digital advertising and as such partly explains the varied effectiveness of marketing actions within multichannel firms. Besides the multi-element configuration, our meta-analysis reveals that some multichannel firms were more effective with marketing actions possibly due to the sequence with which they expanded their distribution channel portfolio. Specifically, firms that added online channels to their legacy physical stores report higher MAE than firms that show other sequences of channel addition (e.g., adding physical stores to online channels or adding a mobile mode to existing channels). Thus, distribution channel addition sequences might indicate unobservable differences in marketing ability that if ignored could contribute to omitted variable bias.

In addition to the hypothesized effects, we provide some additional insights regarding MAE estimates in the literature on distribution channel. For instance, in column 2, Table 3, we show that MAE estimates are not biased by the type of data (primary vs. archival), which implies that researchers need not be concerned about biased conclusions due to the nature of data. This is encouraging for scholars in this area who have access to one data type and not the other. In terms of methodology, we find that studies that account for endogenous regressors indicate significantly lower MAE estimates than those that do not. This suggests that multichannel distribution studies that ignore endogenous regressors possibly over-estimate the performance of marketing actions. Thus, endogeneity corrections are crucial in an empirical analysis of multichannel marketing data.

Implications for managers

Our findings suggest that multichannel firms can improve their marketing action effectiveness by configuring pull marketing actions with factors related to distribution channel structure, customers, competitors and product category. To make more specific recommendations, we set up several scenarios that a multichannel firm’s manager may encounter in terms of channel variety and richness, customer experience, market competitiveness, and infrequently purchased product category or IFPG. We discuss our recommendations for pull marketing actions in each scenario next. These recommendations are summarized in Table 4.

First, multichannel firms that possess a variety of channels should engage more proactively in price promotions across all channels than firms with less channel variety. Second, multichannel firms that offer a physical channel to consumers (compared to those that do not) can benefit more by engaging in digital advertising. Third, multichannel firms can benefit more by targeting more of their digital advertising budgets to experienced customers rather than new or potential customers considering firms’ knowledge of customers’ past purchases and interactions. Fourth, multichannel firms operating in competitive markets should provide price promotions in every channel and use digital advertising that emphasizes every channel in the distribution portfolio. Finally, multichannel firms selling infrequently purchased product categories gain more from using digital advertising and price promotions across channels than firms that sell frequently purchased product categories. Thus, firms selling infrequently purchased product categories should deploy digital advertising and price promotions with more intensity than firms selling frequently purchased product categories.

Future research

Possibility of unobservable characteristics

Many of the variables used in our study could reflect unobserved firm capabilities. Due to such unobservable characteristics, our meta-analysis provides generalizable associations rather than causal effects.

Fine-grained approaches to channel configurations

Because of the high variability in channel configurations and restricted data availability, we only tested different channel modes. However, we acknowledge that there are many more fine-grained channel configurations such as mobile website, app, the 3rd party app, and desktop website that future research should consider.

A broader range of pull marketing actions

Some noteworthy variables had to be excluded from our analysis because of data availability. For example, absolute price levels, penetration pricing, and product variations across channels are relevant yet missing in our sample. Thus, we suggest conducting future research in these pull marketing actions.

Accounting for “push” marketing actions

Push marketing actions are adopted by multichannel firms for trade intermediaries. We did not have any data on push marketing actions in our sample, but future research can look at the tradeoff between push and pull marketing actions to understand their relative effectiveness in specific distribution channels.

Notes

We use the terms “distribution channel” and “channel” interchangeably. Channel, in this study, refers solely to distribution channels and not communication channels such as media outlets. Although communication is certainly possible via distribution channels such as by using display ads within online websites, we take the perspective of distribution.

We reviewed meta-analytic studies published in major marketing journals up until 2021 to confirm that we have sufficient data to conduct a meta-analysis. The number of articles used in previous meta-analytic studies ranges from 9 (e.g., Tellis and Wernerfelt 1987) to 1,030 (e.g., Peterson 1994), and the number of effect sizes varies from 11 (e.g., Cox et al., 1997) to 11,874 (e.g., Homburg et al., 2012). We thus conclude that our research contains an adequate number of studies for a meta-analysis.

Although there are many types of digital advertising, studies mostly investigate one or the other. Due to the large missing values of every single type of digital advertising, we are unable to separately consider them theoretically and empirically. As a result, we club everything under the umbrella of digital advertising.

We recognize that the opposite is less likely to happen such that showrooming customers (if they can be tracked in physical stores, which is difficult in itself) are less likely to purchase online from the same multichannel firm (Forbes, 2016).

These journals include the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research, Journal of Interactive Marketing, Journal of Retailing, Journal of Marketing Channels, Marketing Science, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Management Science, Journal of Service Research, Marketing Letters, Quantitative Marketing and Economics, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Journal of Business Research, European Journal of Marketing, Information Systems Research, MIS Quarterly, Strategic Management Journal, Decision Sciences, Decision Support Systems, Industrial Marketing Management. Many other journals were although not considered as major marketing journals publishing multichannel distribution-related work. Several such journals did not turn up in many of our electronic databases but did turn up on Google Scholar. For example, we considered studies in Journal of International Marketing, International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, to name a few. We included region-specific journals as well such as Asia–Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics as they showed up on Google Scholar. We note that these studies form a preliminary sample, and many studies were eliminated based on the inclusion criteria that we describe next.

Marketing actions encompass all types of 4 P elements or marketing-mix deployed by multichannel firms.

This happens when the authors employ different modeling techniques. For example, in Breugelmans and Campo (2016), we collected 72 MAEs measuring how a multichannel firm’s price promotion affects its business performance. The researchers investigated this IV–DV relationship based on 12 samples of different customer segments, product types (e.g., milk vs. cereal), and modeling techniques (i.e., homogenous vs. heterogeneous models). For each sample, we extracted six MAEs measuring the cross-channel (online and offline) price promotion effects (i.e., contemporaneous, lagged, and frequency). In a similar vein, Gu, and Kannan (2021) employed three versions of DID to investigate the heterogeneities of the treatment effect of mobile app adoption on customers’ multichannel spending. The authors set up 10 groups among six customer segments for comparison (i.e., Segment 1 vs. 3, 4, 5, and 6 respectively; 2 vs. 4, 5, 6 respectively, 3 vs. 5, 6 respectively, and 4 vs. 6). Eventually, we collected 30 MAEs (10 groups $$\times $$ 3 modeling techniques) from this study.

We should also control for the total number of channels in the distribution portfolio. However, the number of channels correlates substantially with channel variety (.71), which precludes us from using the number of channels as a control in the analysis.

References

Ailawadi, K. L., & Farris, P. W. (2017). Managing multi-and omni-channel distribution: Metrics and research directions. Journal of Retailing, 93(1), 120–135.

Ailawadi, K. L., & Farris, P. W. (2020). Getting multi-channel distribution right. John Wiley & Sons.

Akturk, M. S., Ketzenberg, M., & Heim, G. R. (2018). Assessing impacts of introducing ship-to-store service on sales and returns in omnichannel retailing: A data analytics study. Journal of Operations Management, 61, 15–45.

Alba, J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(4), 411–454.

Almarashdeh, I., Jaradat, G., Abuhamdah, A., Alsmadi, M., Alazzam, M. B., Alkhasawneh, R., & Awawdeh, I. (2019). The difference between shopping online using mobile apps and website shopping: A case study of service convenience. International Journal of Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management Applications, 11, 151–160.

Ansari, A., Mela, C. F., & Neslin, S. A. (2008). Customer channel migration. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(1), 60–76.

Arnold, T. J., & Palmatier, R. W. (2012). Channel Relationship Strategy. Handbook of Marketing Strategy. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Assmus, G., Farley, J. U., & Lehmann, D. R. (1984). How advertising affects sales: Meta-analysis of econometric results. Journal of Marketing Research, 21(1), 65–74.

Ataman, M. B., Van Heerde, H. J., & Mela, C. F. (2010). The long-term effect of marketing strategy on brand sales. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(5), 866–882.

Aydinli, A., Bertini, M., & Lambrecht, A. (2014). Price promotion for emotional impact. Journal of Marketing, 78(4), 80–96.

Bala, M., & Verma, D. (2018). A critical review of digital marketing. International Journal of Management, IT & Engineering, 8(10), 321–339.

Barney, J. B. (2014). How marketing scholars might help address issues in resource-based theory. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(1), 24–26.

Bell, D. R., Gallino, S., & Moreno, A. (2018). Offline showrooms in omnichannel retail: Demand and operational benefits. Management Science, 64(4), 1629–1651.

Bell, D. R., Gallino, S., & Moreno, A. (2020). Customer supercharging in experience-centric channels. Management Science, 66(9), 4096–4107.

Bijmolt, T. H., Van Heerde, H. J., & Pieters, R. G. (2005). New empirical generalizations on the determinants of price elasticity. Journal of Marketing Research, 42(2), 141–156.

Bilgicer, H. (2014). Driver and Consequences of Multichannel Shopping. Columbia University.

Biyalogorsky, E., & Naik, P. (2003). Clicks and mortar: The effect of on-line activities on off-line sales. Marketing Letters, 14(1), 21–32.

Bleier, A., & Eisenbeiss, M. (2015). The importance of trust for personalized online advertising. Journal of Retailing, 91(3), 390–409.

Bradford, T. W., & Boyd, N. W. (2020). Help me help you! Employing the marketing mix to alleviate experiences of donor sacrifice. Journal of Marketing, 84(3), 68–85.

Breugelmans, E., & Campo, K. (2016). Cross-channel effects of price promotions: An empirical analysis of the multi-channel grocery retail sector. Journal of Retailing, 92(3), 333–351.

Briedis, H., Kronschnabl, A., Rodriguez, A., & Ungerman, K. (2020). Adapting to the next normal in retail: The customer experience imperative. Retrieved May 1, 2021, from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/adapting-to-thenext-normal-in-retail-the-customerexperience-imperative

Brynjolfsson, E., Hu, Y., & Rahman, M. S. (2009). Battle of the retail channels: How product selection and geography drive cross-channel competition. Management Science, 55(11), 1755–1765.

Cambra-Fierro, J., Kamakura, W. A., Melero-Polo, I., & Sese, F. J. (2016). Are multichannel customers really more valuable? An analysis of banking services. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 33(1), 208–212.

Cambra-Fierro, J., Melero-Polo, I., Patrício, L., & Sese, F. J. (2020). Channel habits and the develoMAEnt of successful customer-firm relationships in services. Journal of Service Research, 23(4), 456–475.

Campo, K., & Breugelmans, E. (2015). Buying groceries in brick and click stores: Category allocation decisions and the moderating effect of online buying experience. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 31, 63–78.

Cao, L., & Li, L. (2015). The impact of cross-channel integration on retailers’ sales growth. Journal of Retailing, 91(2), 198–216.

Cao, L., Liu, X., & Cao, W. (2018). The effects of search-related and purchase-related mobile app additions on retailers’ shareholder wealth: The roles of firm size, product category, and customer segment. Journal of Retailing, 94(4), 343–351.

Chan, J., Wang, Y., Xu, K., & Chen, X. (2021). The Role of Physical Stores in the Digital Age: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Product Level Analysis. Available at SSRN 3762286.

Chandon, P., Wansink, B., & Laurent, G. (2000). A benefit congruency framework of sales promotion effectiveness. Journal of Marketing, 64(4), 65–81.

Chang, C.-W. (2012). Multichannel Marketing and Hidden Markov Models. University of Washington, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 3521641.

Chang, C.-W., & Zhang, J. Z. (2016). The effects of channel experiences and direct marketing on customer retention in multichannel settings. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 36, 77–90.

Chen, B. X. (2018). Are Targeted Ads Stalking You? Here’s How to Make Them Stop. Retrieved November 1, 2021 from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/15/technology/personaltech/stop-targeted-stalker-ads.html

Chiu, H.-C., Hsieh, Y.-C., Roan, J., Tseng, K.-J., & Hsieh, J.-K. (2011). The challenge for multichannel services: Cross-channel free-riding behavior. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 10(2), 268–277.

Choi, S., & Mattila, A. S. (2009). Perceived fairness of price differences across channels: The moderating role of price frame and norm perceptions. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 17(1), 37–48.

Chu, J., Chintagunta, P. K., & Vilcassim, N. J. (2007). Assessing the economic value of distribution channels: An application to the personal computer industry. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(1), 29–41.

Coughlan, A. T., & Jap, S. D. (2016). A field guide to channel strategy. Building routes to market: CreateSpace.

Cox, E. P., III., Wogalter, M. S., Stokes, S. L., & Murff, E. J. T. (1997). Do product warnings increase safe behavior? A meta-analysis. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 16(2), 195–204.

Cui, T. H., Ghose, A., Halaburda, H., Iyengar, R., Pauwels, K., Sriram, S., Tucker, C., & Venkataraman, S. (2021). Informational challenges in omnichannel marketing: remedies and future research. Journal of Marketing, 85(1), 103–120.

De Haan, E., Kannan, P., Verhoef, P. C., & Wiesel, T. (2018). Device switching in online purchasing: Examining the strategic contingencies. Journal of Marketing, 82(5), 1–19.

Deleersnyder, B., Geyskens, I., Gielens, K., & Dekimpe, M. G. (2002). How cannibalistic is the Internet channel? A study of the newspaper industry in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19(4), 337–348.

Denson, N., & Seltzer, M. H. (2011). Meta-analysis in higher education: An illustrative example using hierarchical linear modeling. Research in Higher Education, 52(3), 215–244.

Desai, V. (2019). Digital Marketing: A Review. International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development, 5(5), 196–200.

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99–113.

Dinner, I. M., Heerde Van, H. J., & Neslin, S. A. (2014). Driving online and offline sales: The cross-channel effects of traditional, online display, and paid search advertising. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(5), 527–545.

Du, K. (2018). The impact of multi-channel and multi-product strategies on firms’ risk-return performance. Decision Support Systems, 109, 27–38.

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463.

Edeling, A., & Fischer, M. (2016). Marketing’s impact on firm value: Generalizations from a meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(4), 515–534.

Eisend, M. (2014). Shelf space elasticity: A meta-analysis. Journal of Retailing, 90(2), 168–181.

Fan, Y., & Yang, C. (2020). Competition, product proliferation, and welfare: A study of the US smartphone Market. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 12(2), 99–134.

Fassnacht, M., & Unterhuber, S. (2016). Consumer response to online/offline price differentiation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 28, 137–148.

Fisher, M. L., Gallino, S., & Xu, J. J. (2019). The value of rapid delivery in omnichannel retailing. Journal of Marketing Research, 56(5), 732–748.

Flores, J., & Sun, J. (2014). Online versus in-store: Price differentiation for multi-channel retailers. Journal of Information Systems Applied Research, 7(4), 4.

Fong, N. (2012). Targeted marketing and customer search. ACR North American Advances in Consumer Research, 40, 943–944.

Forbes. (2016). Customers Like to Research Online but Make Big Purchases in Stores, Says New Retailer Study. Retrieved Dec 1, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbespr/2016/05/25/customers-like-toresearch- online-but-make-big-purchases-in-stores-says-new-retailer-study/sh=9ba945f244bb

Fornari, E., Fornari, D., Grandi, S., Menegatti, M., & Hofacker, C. F. (2016). Adding store to web: Migration and synergy effects in multi-channel retailing. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 44(6), 658–674.

Gallino, S., & Moreno, A. (2014). Integration of online and offline channels in retail: The impact of sharing reliable inventory availability information. Management Science, 60(6), 1434–1451.

Gallino, S., Moreno, A., & Stamatopoulos, I. (2017). Channel integration, sales dispersion, and inventory management. Management Science, 63(9), 2813–2831.

Gans, N. (2002). Customer loyalty and supplier quality competition. Management Science, 48(2), 207–221.

Gao, F., & Su, X. (2017). Omnichannel retail operations with buy-online-and-pick-up-in-store. Management Science, 63(8), 2478–2492.

Gatignon, H. (1993). Marketing-mix models. Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science, 5, 697–732.

Gemmill, M. C., Costa-Font, J., & McGuire, A. (2007). In search of a corrected prescription drug Elasticity estimate: A meta-regression approach. Health Economics, 16(6), 627–643.

Gensler, S., Neslin, S. A., & Verhoef, P. C. (2017). The showrooming phenomenon: It’s more than just about price. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 38, 29–43.

Gensler, S., Verhoef, P. C., & Böhm, M. (2012). Understanding consumers’ multichannel choices across the different stages of the buying process. Marketing Letters, 23(4), 987–1003.

Goldfarb, A. (2014). What is different about online advertising? Review of Industrial Organization, 44(2), 115–129.

Grewal, D., Puccinelli, N., & Monroe, K. B. (2018). Meta-analysis: Integrating accumulated knowledge. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46(1), 9–30.

Gu, X., & Kannan, P. (2021). The dark side of mobile app adoption: Examining the impact on customers’ multichannel purchase. Journal of Marketing Research, 58(2), 246–264.

Gupta, S., Lehmann, D. R., & Stuart, J. A. (2004). Valuing customers. Journal of Marketing Research, 41(1), 7–18.

Hanbury, M. (2020). Zara’s owner says it will close as many as 1,200 stores as it doubles down on online shopping. Retrieved Dec 1, 2021, from https://www.businessinsider.com/zara-inditex-invests-in-online-shopping-post-pandemic-2020-6

Hailey, V. (2015). A Correlation Study of Customer Relationship Management Resources and Retailer Omnichannel Strategy Performance. Northcentral University.

Hartung, A. (2016). The 10 Telltale Signs of Future Troubles for Walmart. Retrieved November 1, 2021 from https://adamhartung.com/the-10-telltale-signs-of-future-troubles-for-walmart/

Herziger, A., & Hoelzl, E. (2017). Underestimated Habits: Hypothetical Choice Design in Consumer Research. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2(3), 359–370.

Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Reimann, M., & Schilke, O. (2012). What drives key informant accuracy? Journal of Marketing Research, 49(4), 594–608.

Homburg, C., Lauer, K., & Vomberg, A. (2019). The multichannel pricing dilemma: Do consumers accept higher offline than online prices? International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36(4), 597–612.

Honka, E., Hortaçsu, A., & Vitorino, M. A. (2017). Advertising, consumer awareness, and choice: Evidence from the US banking industry. The RAND Journal of Economics, 48(3), 611–646.

Hox, J. J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge.

Huang, L., Lu, X., & Ba, S. (2016). An empirical study of the cross-channel effects between web and mobile shopping channels. Information & Management, 53(2), 265–278.