Abstract

Many new marketing strategies falter in the execution phase where managers fail to make frontline employees fully committed to implementing the new initiatives. While formal managers can apply transformational and transactional leadership behaviors to increase salespeople’s strategy commitment, peers can also exert a great deal of informal influence on salespeople. Building on recent social network perspectives of leadership, this paper investigates the interplay between the sales manager’s leadership styles and peer effects during the implementation of a new strategy in a large sales organization. The authors find that salespeople with high network centrality but low strategy commitment not only lower their peers’ commitment but also hurt the effectiveness of a transformational manager. Specially, the influence of a central salesperson becomes stronger when the sales group has lower external connectivity. However, sales managers’ transactional leadership can decrease the non-committed central salesperson’s influence over peers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Marketers need to constantly revise or abolish existing strategies and introduce new ones to keep pace with environmental and market changes (Reeves and Deimler 2011). Arguably, however, the real challenge for most marketers lies not in deciding which new direction to take, but in how effectively their organizations will embrace the changes and implement the new strategies (Neilson et al. 2008). Especially in the boundaries of the organizations, successful execution of new strategies almost always demands frontline employees’ complete engagement and full commitment.

Salespeople play such an integral role in developing and nurturing customer relationships that they can directly influence customer loyalty (Palmatier et al. 2007). On the flip side, however, their critical role allows them to easily hurt strategic initiatives that they are not committed to. For example, unaligned salespeople can circumvent new pricing strategies and sign suboptimal deals to attain their own quota (Hinterhuber and Liozu 2012), undersell new products (Ahearne et al. 2010b), or withhold customer information from salespeople of other business units during the implementation of a cross-selling strategy (Duclos et al. 2007). Therefore, gaining salespeople’s strategy commitment is crucial and, at the same time, can be enormously challenging.

These challenges highlight the decisive role of leadership in aligning salespeople’s interests with the new direction and gaining their support throughout the implementation phase. To study the role of leaders in a sales context, researchers have predominantly drawn from classic leadership theories (MacKenzie et al. 2001; Schmitz et al. 2014; Shamir et al. 1993; Wieseke et al. 2009; Yukl 2002). A tacit, yet central premise of these theories is a view of leadership as a formal and action-oriented phenomenon confined to managers. However, this top-down conception of leadership is challenged by increasing complexities in sales processes and flatter and more flexible management structures, which all support a more relational and distributed notion about leadership (Flaherty et al. 2012; Mehra et al. 2006). Facing sophisticated customers and complicated sales processes, salespeople need to leverage their relationships with their peers to gain insights on how to handle a situation, push their case faster internally, or overcome administrative or technical obstacles (Plouffe et al. 2016; Schmitz and Ganesan 2014). As a result, salespeople have become so heavily dependent on their internal networks that they can hardly avoid being influenced by key colleagues (Fuller 2014).

Realizing the need for an alternative view of leadership, researchers have recently proposed a social network perspective to leadership (Balkundi & Kilduff, 2006; Carter et al., 2015; Flaherty et al., 2012). This perspective on leadership is born out of topical definitions of leadership as a dyadic, relational, and social dynamic (Avolio, Walumbwa, & Weber, 2009). Social network perspectives define leadership as a relational phenomenon that involves building and using social capital (Balkundi & Kilduff, 2006; Carter et al., 2015). According to these perspectives, leadership (1) can be informal or formal, suggesting that leaders do not necessarily occupy formal positions, (2) is relational, meaning that leadership is associated with relationships among individuals rather than being merely about certain managerial actions, (3) is embedded within the social ties among actors, indicating that leaders could be identified by the degree to which they are central to the network of social links among colleagues, and (4) is patterned, implying that the structural pattern of how actors in the network connect affects the influence of leaders (Balkundi & Kilduff, 2006; Carter et al., 2015).

In this research, we build on social network perspectives of leadership to identify informal leaders within sales groups and juxtapose their influence on salespeople’s strategy commitment with the formal sales manager’s influence exerted through traditional leadership styles. To do this, we tracked the implementation of a new product strategy in a large media corporation that historically had sold print advertisement space but was adding online advertisement space to its product portfolio and trying to shift its sales emphasis to the new product line.

Of particular interest to our research is how the informal influence of peers interacts with the well-researched formal manager’s leadership styles, which are often classified under two general styles: transformational leadership, or leading by inspiring, and transactional leadership, or leading by providing positive and negative feedback (MacKenzie et al. 2001). We argue that salespeople who are often the go-to colleague in everyday work-related matters play an integral role in helping or harming the efforts of a transformational leader, since they are the ones who help the broader vision crystallize into concrete task-related guidelines. Although inspiring, transformational leaders often leave the mechanics of how to get to an advocated vision to employees (Shamir et al. 1993; Grant 2012). Therefore, followers of a transformational leader often need to seek advice from peers to better translate the vision to the specific task in hand (Zhang and Peterson 2011) and hence are more susceptible to the informal influence of central peers. We demonstrate that non-committed salespeople who are central in advice networks hurt the effectiveness of transformational leadership. On the other hand, a sales manager’s transactional leadership, which traditionally was believed to be inferior to the transformational style, can reduce the negative informal influence of non-committed central peers by defining a clear roadmap and an incentive system to guide salespeople’s intentions and behaviors.

Our research significantly contributes to both the theory and practice of sales leadership. First, in line with recent theoretical work (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006; Carter et al. 2015; Flaherty et al. 2012), we take a social network perspective to leadership. A concomitant of such a perspective is that leadership is no longer confined to formal organizational position of an individual; instead, any particular salesperson with high degree centrality can influence peers’ attitudes and actions. More importantly, our novel findings suggest that the traditionally studied leadership behaviors interact with informal paths of influence to determine salespeople’s new strategy commitment.

Second, prior studies on leadership styles have mostly treated transformational leadership as a magic bullet that usually works well and is superior to transactional leadership behaviors (MacKenzie et al. 2001). We add a vital contingency to the effectiveness of transformational leadership and demonstrate that transactional leadership becomes preferable to the transformational style when influential salespeople are not aligned with sales managers and have unfavorable effects on their peers. This finding is rooted in the underlying process of influence via these behavioral leadership styles. Transformational leadership is about intrinsic motivation, while the transactional style ties performance to extrinsic consequences (i.e., recognition or rebuke). Our results suggest that when it comes to intrinsic motivation, rhetoric might not be enough. Instead, the relational aspect of leadership is of paramount importance when the goal is to internally motivate salespeople.

Third, our results provide clear and actionable implications for managers. According to our findings, a central salesperson’s lack of strategic commitment can have detrimental effects on peers when salespeople in the group have, on average, a low number of ties with peers from other sales groups. These are sales groups that have little interaction with other groups and implement strategies in relative isolation from others. One option for managers in these groups is to adapt a transactional leadership style by tying salespeople’s performance and behavior to contingent reward and punishment (MacKenzie et al. 2001), making salespeople less sensitive to the central but uncommitted salesperson’s influence in their sales group. Alternatively, managers can act as network engineers by facilitating interactions across different sales groups via meetings, conferences etc. This could help salespeople find other sources of advice who are potentially more supportive of the new changes. Moreover, our findings suggest that managers who want to apply a transformational leadership style should also have their doors open for giving advice. Managers whose subordinates more frequently and easily access them for advice build the necessary informal leadership stature to more effectively apply a transformational style.

Conceptual framework

Marketing strategy implementation

A review of the literature on marketing strategy implementation reveals that despite a long-standing interest in the topic (Bonoma 1984) and some notable contributions (Ahearne et al. 2010a; Sarin et al. 2012), the collective body of literature remains limited (Chimhanzi and Morgan 2005). Building on the assumption that implementers are influenced by only their own (and not their peers’) beliefs, perceptions, and motivations, researchers have mainly focused on three questions: (1) What individual factors, such as beliefs, attitudes and behaviors, contribute to adapting to and implementing changes (Ahearne et al. 2010a)? (2) Which formal organizational levers, such as incentives, control systems, or job characteristics, influence those individual factors (Noble and Mokwa 1999; Walker and Ruekert 1987)? (3) How can a given strategy be framed in a psychologically favorable way (e.g., revenue-enhancing versus costly or outcome-oriented versus process-oriented) to enhance individual perceptions of that strategy (Sarin et al. 2012; Ye et al. 2007)? Extant research does not address the role of peers in shaping salespeople’s commitment to new strategies, however.

Previous research on the outcomes of strategy implementation argues that strategy implementers’ commitment to their roles is key for maximizing the outputs of the strategy (Noble and Mokwa 1999). Thus, strategy role commitment, defined as employees’ determination to effectively perform individual implementation responsibilities, is an important predictor of successful strategy implementation (Dess and Origer 1987; Noble and Mokwa 1999; Wooldridge and Floyd 1989). However, previous literature does not address the role of leadership styles or peer effects in shaping employees’ strategy role commitment.

Leadership theories in sales research

Recognizing the critical role of salespeople in actualizing firm strategies, researchers have long attempted to identify managerial behaviors that better align salespeople’s commitment and actions with the desired direction. Drawing from leadership theories in organizational psychology, sales researchers have mostly focused on two groups of supervisory behaviors.

The first group of behaviors stemmed from the theory of supervisory feedback or leader-reinforcing behavior (e.g., Kohli 1985; Podsakoff et al. 1984), which postulates that sales managers should provide both positive feedback (e.g., recognition, approval) and negative feedback (e.g., rebuke, disapproval) to salespeople contingent on their effort or performance. Due to the give-and-take nature of these types of behaviors, they are often called transactional leadership (MacKenzie et al. 2001). Salespeople who work under a transactional leader know that positive or negative feedback will await them, depending on their degree of success in fulfilling the assigned tasks. The underlying influence process of this type of leadership is one of compliance rather than internalization (MacKenzie et al. 2001).

The second stream of research started from the observation that certain managers, often called charismatic (e.g., Shamir et al. 1993) or transformational (MacKenzie et al. 2001) leaders, rely on inspirational appeals rather than supervisory feedback to motivate their subordinates. In particular, transformational leaders are known to articulate a compelling vision, emphasize group goals, express optimism about the future, expect higher performance, and encourage creative thinking (MacKenzie et al. 2001; Shamir et al. 1993). The gist of transformational leadership is stimulating individuals to transcend their own self-interests and move toward a promoted vision. Research on leadership styles has generally found transformational leadership to be more effective than transactional leadership. Table 1 summarizes prior findings of leadership research in sales management.

However, the extant literature has limited its focus to formal managers. This manager-centered perspective does not depict a complete portrait of reality, since salespeople often look to more than their formal manager for leadership. In fact, as sales leadership structures have become flatter, the importance of “behind the chart” relationships has increased such that the main influencer in many sales teams might not necessarily occupy a formal leadership position. Recognizing these changes, researchers have recently called for empirical work that combines traditional leadership theories with social network research (Carter et al. 2015; Flaherty et al. 2012). We explain these new social network perspectives of leadership in the next section.

In addition, prior research mostly treats the transformational style as a panacea for sales leadership and finds it to be superior to the transactional style. Scant attention has been paid to potential contingencies under which the transformational style might not be as effective or be inferior to the transactional style. We fill these gaps in the sales leadership literature by offering some of these contingencies.

Social network perspectives of leadership

The social network perspectives of leadership (Carter et al. 2015; Balkundi and Kilduff 2006; Flaherty et al. 2012) build on four attributes of leadership that are best characterized by core concepts developed in the social network theory. These contemporary views entail that leadership is (1) potentially formal and/or informal, (2) relational, (3) embedded within social ties, and (4) patterned (Carter et al. 2015; Balkundi and Kilduff 2006). We build on these contemporary leadership perspectives to develop the theoretical foundation of our study.

Characteristics

The formal/informal characteristic indicates that formal sources of power are not the only paths to influencing employees and salespeople do not merely look to their manager for leadership (Flaherty et al. 2012; Mehra et al. 2006). Instead, leadership involves building and using social capital (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006). This means that the arrangement of social connections surrounding an actor defines the degree to which the actor can have an impact on the attitudes and behaviors of his/her connections. Thus, regardless of their formal position, actors with high centrality can exert an informal type of leadership by utilizing their network centrality to shape their peers’ organizational attitudes and behaviors.

The relational attribute of leadership indicates that as much as leadership is about leader’s characteristics and behaviors, it is also about the relationships among individuals. Traditional leadership theories have largely placed leaders under personological and behavioral microscopes. In contrast, the most distinguishing feature of social network research is its emphasis on the relationships among actors.

The third characteristic draws from the concept of embeddedness in social network theory to posit that leadership is also embedded within the social context. Therefore, social network perspectives of leadership indicate that salespeople’s perceptions of peers as leaders are reflected through a set of embedded ties within which those peers are located (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006). Highly embedded actors (i.e., high degree centrality) can utilize their centrality to influence the high number of peers to which they are connected.

Finally, a key concept in social network theory, structural patterning, is also an important feature in leadership. To understand who is a leader, social network perspectives of leadership suggest that researchers should investigate the social-structural positions occupied by particular actors as well as the patterns of relationships among all actors in the network (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006; Carter et al. 2015). This means that the effectiveness of leaders would also depend on the way other salespeople connect to each other (e.g., whether relationships among individuals include ties to actors from other networks). In a sales context, this would imply that effective sales managers should act as “network engineers,” able to detect who is connected to who and link unconnected actors when necessary (Flaherty et al. 2012).

To summarize, these four characteristics indicate that actors with high degree centrality can influence their peers regardless of their formal position. We draw on these social network perspectives of leadership to identify informal leaders within sales groups and study the interplay of their peer influence with the formal influence of sales managers which is mainly applied through traditional leadership styles (i.e., transformational and transactional).

Relational ties

Social network perspectives of leadership express leadership as a relational phenomenon incorporating relationships among individuals. Two types of relationships widely investigated in the literature are advice-seeking and friendship ties (Kilduff and Brass 2010). Despite a possible overlap between the two types of ties, they are theoretically distinct and lead to different types of outcomes (Borgatti and Foster 2003). While friendship ties are predictive of social-related outcomes, such as job satisfaction or the degree to which a team retains its members (i.e., team viability), advice-seeking ties are mostly related to job- and duty-related outcomes, such as task performance (Guzzo and Dickson 1996). The former outcomes (e.g., team viability) are considered as prerequisites of long-term functioning, while the latter involve meeting or exceeding expectations from specified work assignments (Gladstein 1984). Since in this research we are concerned with the extent to which salespeople commit to executing new marketing strategies, we narrow our focus to advice-seeking ties.

Degree centrality and group external connectivity

Prior research indicates that certain network positions confer special advantages to actors occupying those positions (Borgatti and Foster 2003; Brass 1984). The most important network position to occupy is a central position (Brass 2011; Brass et al. 2004). However, network literature has identified multiple centrality measures, each relating to a different concept and resulting in different outcomes. Of all these different centrality measures, “degree centrality” is the most germane to investigating leadership effects. In an advice-seeking social network, degree centrality refers to the extent to which an individual is sought after for advice by peers or subordinates (Borgatti 2005; Ibarra 1993). Other widely studied centrality measures include closeness, which captures access to resources, betweenness which captures information control, and eigenvector centrality which captures closeness to dominant players (for a review see Brass et al. 2004). While these types of centralities help the individual performance of the central actor by endowing him/her with strategic access to resources, key players, or information (e.g., Bolander et al. 2015; Gonzalez et al. 2014), they are less related to influencing the performance of those connected to the central actor (Brass 1984, 2011; Brass et al. 2004). Instead, individuals with high degree centrality in advice networks are frequent sources of advice to a large number of their peers or subordinates. These “go-to” colleagues might be experts with an incredible openness to help their colleagues, star salespeople who frequently share the tips of the trick with their peers, or high-tenure sales reps whose opinions are highly sought after. We refer to the salesperson with the highest level of degree centrality among peers in a sales group as the “central salesperson.” We also define the “degree centrality” for sales managers as the extent to which salespeople regularly refer to their sales manager for advice on work-related matters. Sales managers with high degree centrality couple their formal leadership with informal influence.

At the group level, patterns of connections among the group members with members of other groups are critical (Burt 1992, 2000). Groups with more informal ties to individuals from other groups are exposed to more bits of non-redundant perspectives (Burt 2000; Van den Bulte and Wuyts 2007). We argue that these new perspectives, gained from informal connections to outside members can reduce reliance on the informal resources inside the group. In other words, the main advice-giver of the group will be less influential in groups wherein more members seek alternative sources of advice from outside the sales group. This is in line with social network perspectives to leadership that view leadership as a patterned phenomenon and propose formal managers to be network engineers, linking unconnected actors when necessary.

Framework

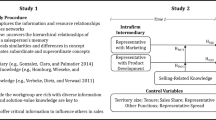

Figure 1 illustrates our conceptual framework. We build on social network perspectives of leadership to model the interplay between formal managerial leadership styles (i.e., transformational and transactional leadership) and the informal influence of peers during strategy implementation. In particular, the four social network characteristics of leadership guided the selection of our variables. The embeddedness and the relational characteristics underscore the importance of degree centrality in work relations for having leadership influence over peers and subordinates. The informal/formal characteristic denotes that leadership is not limited to formal managers; peers who are central in relational networks could also exert significant influence over their colleagues. Drawing from these three characteristics, we include the influence of a central peer’s strategy role commitment as well as a formal manager’s own network centrality in our conceptual model. Moreover, drawing from the fourth characteristic, structural patterning, we include the external connectivity of the sales group which determines whether the pattern of ties between salespeople incorporates external ties with peers from other sales groups.

Hypothesis development

The effect of sales managers’ transformational and transactional leadership

Researchers have consistently recognized leadership behavior as one of the most important factors affecting followers’ motivation and commitment (Deichmann and Stam 2015). Transformational and transactional leadership styles are the collection of constructive leader behaviors and therefore, research on sales leadership has often focused on these two types of leader behaviors. The opposite of these constructive behaviors is often called laissez-faire leadership, or “doing nothing,” which is associated with the lowest possible or even negative outcomes (Skogstad et al. 2007).Footnote 1

However, transactional and transformational leaders use different methods to affect salespeople’s strategy role commitment. Transactional leaders communicate their expectations and both reward and punish salespeople in accordance with the agreed task goals (Bass, 1985; MacKenzie et al. 2001). Salespeople who work with a transactional leader are likely to receive feedback; they receive negative feedback when their behavior or performance falls short of the stated objectives and positive feedback when they meet or exceed the expectations.

On the other hand, transformational leaders motivate salespeople mostly through inspirational and intellectual stimulation (Bass 1985). They promote a shared vision and emphasize collective goals, helping followers to develop a sense of purpose (MacKenzie et al., 2001; Shamir et al. 1993). Moreover, transformation leaders encourage followers to challenge existing assumptions and think differently to find creative ways to contribute to the overall vision (Bass 1985). By engaging in these leadership behaviors, transformational managers seek to motivate salespeople to rise above their immediate self-interests and contribute to the broader vision of the firm (MacKenzie et al. 2001).

H1: Sales managers’ transactional leadership has positive effects on salespeople’s strategy role commitment.

H2: Sales managers’ transformational leadership has positive effects on salespeople’s strategy role commitment.

The moderating role of sales managers’ degree centrality

A higher degree centrality for managers implies that a larger number of salespeople feel free to regularly stop by their office and individually seek their advice on work-related matters. Social network perspectives of leadership identify embeddedness within informal advice networks as an important pillar of effective leadership (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006). According to these theories, central sales managers can utilize their informal ties with their salespeople, to more effectively lead (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006; Flaherty et al. 2012). During the process of implementing a new marketing strategy, more informal interactions with subordinates provide managers with better opportunities to monitor salespeople’s attitudes and behaviors toward the strategy. As a result, managers who benefit from high degree centrality within the advice network of the sales group have more informal ties to subordinates which facilitate the process of giving feedback or guidance to them when necessary.

A transformational sales manager who guides salespeople through inspiration and intellectual stimulation can utilize his/her ties to regularly interact with subordinates, guide and motivate them toward the shared goal, and reduce their ambiguity and frustration with the new strategy. Managers with higher centrality couple their formal power with being highly involved in informal relationships with subordinates. This helps their promoted vision to better connect with salespeople at a personal level. On the other hand, a transactional sales manager who leads via rewards and punishments can utilize his/her centrality to more closely monitor subordinates’ actions and outcomes, ascertain that salespeople are on the right track with regards to implementation tasks, and apply more effective incentive systems (i.e., rewards and punishments) to maximize salespeople’s outcomes.

H1a: The effect of sales managers’ transactional leadership on salespeople’s strategy role commitment is stronger when the manager has higher degree centrality in the sales group.

H2a: The effect of sales managers’ transformational leadership on salespeople’s strategy role commitment is stronger when the manager has higher degree centrality in the sales group.

The informal effect of central peers

According to the embeddedness characteristic in social network views of leadership, actors with high degree centrality in informal networks can influence peers (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006). Centrality in the work-related advice network of sales groups grants central salespeople important benefits. First, because they are the go-to people, the information they provide is viewed as accurate and reliable on work-related matters (Brass et al. 2004). Second, because most of their colleagues seek advice from them, the volume of information that they spread in the group and the number of peers that they directly influence are significantly higher than other salespeople. Third, their centrality gives them high visibility, which translates into positive reputation or prestige in the group (Brass 2011; Brass et al. 2004). In the context of strategy implementation, the information and advice that central salespeople provide to peers with regards to the new strategy is high volume, visible, and perceived as accurate and reliable. Thus, we expect the highly committed central salespeople to provide positive advice and information with regards to the new strategy and lead their peers in the same direction, which, in turn, results in high peer commitment to the new strategy.

Moreover, since implementing a new strategy is usually coupled with uncertainty and ambiguity, salespeople might seek sources of information and advice to reduce their uncertainty and confusion. Central salespeople are, by definition, the main source of advice for work related matters. Therefore, they play a crucial role when salespeople are developing their interpretations of the new strategy. Because they are highly sought after for advice, their beliefs about the new strategy significantly impact the advice seekers. Thus, we expect the positive beliefs of highly committed central salespeople about the new strategy to impact peers in the same way and make them more committed to their roles in strategy implementation:

H3: The central salesperson’s strategy role commitment has a positive effect on peers’ strategy role commitment.

The moderating effect of a sales group’s external connectivity on the informal influence of central salespeople

Social capital theories suggest that, similar to individuals, groups also possess social capital based on the structural pattern of ties among group members with members of other groups (Burt 2000). Advice-seeking ties between salespeople in a sales group contains work-related information. However, ties among actors from the same group carry highly repetitive information (Burt 2000). External sources of information are valuable in providing novel insights, different perspectives, and better understanding of how actors in other groups cope with the same issues (Ahearne et al 2014; Choi 2002).

Moreover, according to social network views of leadership, the pattern of ties among group members with members of other groups is an important determinant of leadership effectiveness (Balkundi and Kilduff 2006; Carter et al. 2015). That is, the effectiveness of leaders also depends on the way that group members connect to members of other groups. In the context of strategy implementation, we argue that the influence of an informal leader (i.e., central salesperson) on peers is dependent on the external connectivity of the sales group.

External connectivity of the sales group affects the type and volume of the information that group members collect and process regarding the new strategy. During the implementation of a marketing strategy, sales groups whose members have advice-seeking ties with salespeople from other sales groups gather information on how other groups are executing the new strategy, how committed they are, and what beliefs and attitudes they have toward the new initiative.

While each sales group is subject to the influence of central peers, we argue that the central peer’s influence decreases in sales groups that have more external ties with other sales groups. Higher external connectivity of the sales group offers salespeople wider perspectives and alternative ideas about the new strategy, making them less sensitive to or dependent on the central peer’s opinions about the new strategy. Thus, the central salesperson’s beliefs about the strategy will be less influential on peers’ strategy commitment since externally connected peers collect and process information from multiple sources other than the central salesperson.

H3a: The effect of the central salesperson’s strategy role commitment on peers’ strategy role commitment is weaker when the sales group has higher external connectivity.

The moderating effect of the central salesperson’s commitment on the impact of sales managers’ transformational leadership

Researchers have shown that individuals use signals and information sent by their managers and peers to shape beliefs about what they should do (Chiaburu and Harrison 2008). The extant literature demonstrates that transformational leaders tend to communicate broad and nonspecific goals that relate more to the overall vision of the firm (MacKenzie et al. 2001; Shamir et al. 1993; Simons 1999). On the other hand, central peers are often referred to for more explicit, everyday work-related matters (Brass et al. 2004). Therefore, during the implementation of a new marketing strategy, central salespeople play a vital role in helping the big picture translate into more concrete task guidelines.

For instance, during the introduction of a new product line or a transition from an old to a new sales technology, transformational leaders delineate how the new direction relates to the general vision of the organization, but are less likely to provide detailed guidance on how to transfer customers to the new product line or how to sell the new technology to new customers. In other words, transformational leaders leave the mechanics of implementing the strategy to salespeople and encourage them to come up with their own ways of executing the new policy (MacKenzie et al. 2001). This particular leadership style increases the followers’ need to refer to their peer sources of advice to figure out the best way to convert the broader vision to explicit know-how (Zhang and Peterson 2011). Therefore, followers of a transformational manager are more susceptible to the informal influence of central peers. Uncommitted central peers could easily hurt a strategic initiative by spreading their opposing views about the advocated vision to their peers who, under a transformational manager, are more in need for advice in order to reduce the uncertainties associated with the new direction.

H4: The effect of sales managers’ transformational leadership on salespeople’s strategy role commitment is weaker when the central salesperson has a lower level of strategy role commitment.

The moderating effect of sales managers’ transactional leadership on the peer effect of the central salesperson

As we explained before, new strategic initiatives generate conditions of ambiguity and uncertainty in sales forces. In order to reduce their uncertainty, salespeople look for trusted sources of advice regarding the new strategy. According to social network perspectives of leadership, informal leaders (i.e., central salespeople) are among the most trusted sources of advice when salespeople are trying to interpret an ambiguous work situation (Balkundi & Kilduff 2006). However, we argue that the peer advice and information of central salespeople might not be crucial to salespeople if formal sales managers directly reduce the task ambiguity of salespeople by applying a transactional leadership style.

Compared to transformational leaders, transactional leaders are known to be more specific about their expectations and lead by contingent reward and punishment (MacKenzie et al. 2001). Due to the rewarding and punitive consequences of their actions, salespeople who work under a transactional leader have a clearer perspective on what actions to take in order to secure rewards and avoid punishments from their managers. Since transactional leadership style provides specific reward and punishment to direct the behaviors of subordinates, salespeople are less in need of referring to alternative sources of advice such as their central peers. In fact, following the feedback provided by transactional sales managers will expose salespeople to less risk compared to trusting information and advice from secondary sources such as central salespeople. Therefore, salespeople become less sensitive to and dependent on the central salesperson’s influence. Thus:

H5: The effect of the central salesperson’s strategy role commitment on peer salespeople’s strategy role commitment is weaker when the sales manager increases his/her use of transactional leadership style.

Performance impacts of the sales group’s strategy role commitment

If we compare strategy implementation with a specific goal that salespeople want to achieve, the goal setting literature would describe commitment as the determination and extension of effort and attention to accomplish the set goal. Previous studies have shown that when everyone is dealing with the same difficult goal, those with higher commitment usually outperform others (H. J. Klein et al. 1999). Marketing strategy implementation literature has also identified role commitment as a major predictor of success in strategy implementation (Noble and Mokwa 1999). Thus, we expect that salespeople’s commitment to diligently perform their implementation responsibilities will result in better chances of achieving the implementation goals. Since the major outcome of the new strategy studied here is improving the sales performance of the new product line, we expect the strategy role commitment of salespeople to result in higher sales performance of the new products.

H6: When salespeople in a sales group have a higher average level of strategy role commitment, the sales group performs better in selling the new products.

Methodology

Research context

We obtained data from the sales division of a leading U.S-based media firm. Similar to many sales organizations in other industries such as pharmaceuticals, insurance, and retailing, the studied sales organization had a hierarchical structure in which a number of salespeople worked under the supervision of a sales manager (average group size: 6.7), and a number of sales managers worked under the leadership of a sales director. The entire sales force was under the supervision of the VP of sales. In this firm, the marketing department was in charge of analyzing market trends and identifying the most promising market segments. Newly agreed-on strategic initiatives were announced to higher-level sales managers so that they could align salespeople with the new strategic directions. This company mainly utilized an outcome-based sales control system. While managers emphasized proper sales procedures, expense control, and use of technical knowledge, salespeople were mainly compensated based on achieving sales quota objectives.

At the beginning of the data collection period, the company had started implementing a new product strategy to gradually shift its focus from selling print advertisement products to offering digital ads to its customers. The sales department was tasked with pushing the newly developed digital products to targeted market segments. Since the media industry had been focusing on selling traditional print ads to marketers for many years, this shift in strategy was considered a significant change in the day-to-day operations of salespeople. A shift to selling digital ads required significant training on digital advertising products. Moreover, salespeople needed to target more digitally oriented advertisers and ad agencies and negotiate with them based on online ad auction pricing models, digital ad placement methods, and ROI-driven advertising analytics. This required the revision of a number of existing customer acquisition and negotiation methods, and modification of current sales techniques.

All the salespeople and sales managers involved in the new strategy went through several sessions of training to get familiar with the new products. The incentive and compensation structure was a commission system based on quota achievement across all the products, which was gradually shifting its focus from traditional ads toward digital ads. Along with the implementation of the new strategy, the rewards system was also revised so that approximately 20% of all the sales compensation was based on new product quota achievement. The company was planning to gradually increase this amount to 50% within the next two years.

Despite all the organizational efforts for smoothing the implementation process, our interviews with a number of salespeople, sales managers, and sales directors in the company revealed a general concern that these changes would impose a significant amount of risk on salespeople, which might result in confusion, frustration and resistance to change. Moreover, managers were worried about the negative, “behind the charts” influence of peers on each other in executing the new initiative. Therefore, we were provided with an appropriate context for studying a top-down strategy implementation within the sales force. Since the scope of change was significant for the company, leadership during the change process and peer effects played critical roles in obtaining the commitment of salespeople. We expect to observe relatively similar situations when sales organizations in other companies implement different types of important marketing strategies. Therefore, we believe that our findings are generalizable to other scenarios of marketing strategy implementation through the sales force.

Data collection

Before the quantitative survey, we conducted a number of interviews with several salespeople, sales managers, and sales directors in the company to get familiar with the nature of the sales organization and the new strategy. The implementation process had started with defining new quotas for selling digital ads. We sent surveys during the beginning stages of the strategy implementation to all salespeople and sales managers involved in the process. We obtained responses from 433 salespeople (65% response rate) and 65 sales managers (88% response rate). Since our study involved the analysis of social networks, we decided not to include groups in which less than half of the salespeople responded to the questionnaire. This would help us avoid some possible missing data problems and enhance the robustness of our analysis. We were finally left with 398 salespeople working in 60 sales groups. Our final response rate, after eliminating sales groups with lower than 50% respondents, was 72% for the salesperson level and 92% for the sales manager level. Therefore, we had a robust case for applying the social network analysis methods. We found no systematic differences between early and late respondents on either demographic variables or major constructs. A brief description of the sample appears in Table 2. We used two separate questionnaires at the salesperson and sales manager levels to measure respective constructs at each level. The strategy role commitment construct was measured at both levels, while other constructs were only measured at the salesperson level.

We also collected objective data from the firm three months later to track the success of the new product strategy. This allows for a time lag between the antecedents (e.g., strategy role commitment) and the outcome (i.e., sales group’s sales performance of the new products) and thereby enhances our causal inference and reduces potential threats arising from common method variance (Rindfleisch et al. 2008).

Measures

All scales used in the study are well-established measures in the literature. Table 3 displays the means, standard deviations, average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability coefficients, and intercorrelation matrix for the focal measures of the study. Questionnaire items, item loadings, measurement scales, and literature sources appear in the Appendix.

Transformational and transactional leadership styles were measured using the well-known scale developed by MacKenzie et al. (2001). We measured strategy role commitment by customizing the scale developed by Noble and Mokwa (1999) to fit our research context. We provided a brief description of the strategy before asking respondents to rate their level of commitment to the strategy. We measured sales group’s sales performance of new products using objective company data on how each sales group had performed in achieving the sales quota of the new products.

In order to map the advice-seeking network and identify the most central salesperson in each sales group, we applied the standard nomination procedure that has been widely used in prior research (Marsden 1990). Specifically, we asked each salesperson to nominate salespeople in his/her sales group to whom he/she regularly referred to for advice on work-related matters. In each sales group, we selected the salesperson with the highest number of incoming advice-seeking ties among peers as the “central salesperson.” In addition, we asked salespeople in each group whether they regularly referred to their sales manager for advice on work-related matters. We counted the number of nominations that each sales manager received from subordinate salespeople and divided it by the total number of salespeople in each group to calculate the “degree centrality” of sales managers in their respective sales groups.

In this paper, we argue for the existence of “central” salespeople with significant amount of influence over their peers. In order to check whether social network patterns actually supported the existence of central salespeople, we calculated the percentage of advice-seeking ties in sales groups that were directed to the salesperson with the highest centrality score among peers. Our results revealed that on average, 42% of all the advice-seeking ties were connected to salespeople with top-ranked centrality scores. Salespeople with the second-ranked centrality scores only attracted an average of 22% of all the advice-seeking ties, and the number dropped to 14% for third-ranked salespeople. Skewed distribution of network ties toward salespeople with the highest number of ties provided clear evidence for the existence of dominant central salespeople in the informal networks of sales groups.

To measure the external connectivity of sales groups, we first mapped the external network of sales groups by asking group members to nominate salespeople outside of their own sales groups to whom their regularly referred to for advice on work-related matters. We counted the total number of outgoing advice ties from a sales group, denoted as E. The total number of advice-seeking ties inside the sales group was denoted as I. Next, we used the E-I index (Krackhardt and Stern 1988) to operationalize the external connectivity of the sales group. This was calculated by (E-I)/(E + I), which shows the dominance of external ties over internal ties in a sales group. A group with a small number of external ties and a high number of internal ties represents a situation in which group members have low external connectivity and prefer to seek the majority of their work-related advice from internal sources.

We controlled for several factors that could potentially influence the new product performance of the sales groups. We controlled for the average sales experience of salespeople in each sales group (sales experience with the company) and the work experience of the sales manager (work experience with the company), using objective data provided by the firm. Moreover, because the strategy implementation scenario was related to new product launching, we controlled for salespeople’s “new product knowledge” by adapting a four-item measure from Behrman and Perreault (1982).

We controlled for the impact of the sales manager’s strategy role commitment on salesperson’s strategy role commitment and found a significant effect (β = .32, p < .05). Since we had singled out the central salesperson from the group, we separately evaluated the impact of the sales manager’s strategy role commitment and leadership styles on the central salesperson’s strategy role commitment. However, we did not find a significant effect for sales managers’ strategy role commitment (β = .08, p > .05), transactional leadership (β = .10, p > .05) or transformational leadership (β = .09, p > .05). This is an interesting finding because, unlike other salespeople, sales managers’ leadership styles do not seem to automatically affect in the central salesperson’s strategy role commitment. A possible explanation is that central salespeople, who have a high status in their sales groups, develop their own perspectives about the new initiatives rather than being heavily influenced by their managers. They might be on board with managers under certain occasions, might be neutral, or might oppose the new strategy. This is in line with previous findings in the distributed leadership literature (Mehra et al., 2006). Even though we did not study the underlying reasons behind this finding, it clearly indicates a potential conflict between the sales manager and the central salesperson when it comes to implementing new strategies. Therefore, it is crucial for sales managers to understand how to decrease the negative peer effects of unaligned central salespeople.

Model specification

In our dataset, salespeople were nested within sales managers. Thus, we applied hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) to account for possible interdependencies and cross-level effects in a sales group. We used full maximum likelihood for estimation to compare model fits across nested models (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). We centered variables at the grand mean level because we were primarily interested in level two predictors (Enders & Tofighi 2007). In order to justify the use of higher level predictors, we first calculated a null model to evaluate whether significant between-group variation existed with regards to salespeople’s strategy role commitment. The results indicate that working under different sales managers made a significant difference in salespeople’s strategy role commitment (χ2 = 463, d.f. =398, p < 0.05). This justifies the addition of predictor variables at the sales manager level. Our final HLM model is as follows:

Model 1: Sales Manager’s Leadership Styles and Central Salesperson’s Strategy Role Commitment ➔ Salesperson’s Strategy Role Commitment (HLM regression)

Level 1 : SRCSPij = β 0j + rij.

Level 2 :\( {\displaystyle \begin{array}{c}\hfill \kern0.1em {\beta}_{0\mathrm{j}}={\gamma}_{00}+{\gamma}_{01}\left({\mathrm{TAL}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)+{\gamma}_{02}\left({\mathrm{TFL}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)+{\gamma}_{03}\left({\mathrm{SRCCSP}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)+{\gamma}_{04}\left({\mathrm{SRCSM}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)+{\gamma}_{05}\left({\mathrm{TAL}}_{\mathrm{j}}\times {\mathrm{DCSM}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)+{\gamma}_{06}\hfill \\ {}\hfill \left({\mathrm{TFL}}_{\mathrm{j}}\times {\mathrm{DCSM}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)+{\gamma}_{07}\left({\mathrm{TAL}}_{\mathrm{j}}\times {\mathrm{SRCCSP}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)+{\gamma}_{08}\left({\mathrm{SRCCSP}}_{\mathrm{j}}\times {\mathrm{TFL}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)+{\gamma}_{09}\left({\mathrm{SRCCSP}}_{\mathrm{j}}\times {\mathrm{ECSG}}_{\mathrm{j}}\right)\hfill \\ {}\hfill +{\mathrm{u}}_{0\mathrm{j}}.\kern0.5em \left(\mathrm{for}\kern0.1em \mathrm{salesperson}i\mathrm{insalesgroup}j\right)\hfill \end{array}} \)

Finally, we applied an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to test the impact of salespeople’s strategy role commitment on each sales group’s sales performance:

Model 2: Salespeople’s Strategy Role Commitment ➔ Sales Group’s Sales Performance (OLS regression)

SPSGj = α 0 + α 1(AVE_SRCSPj) + α 2(AVE_SEXPSPj) + α 3(AVE_PKNOWSPj) + α 4(WEXPSMj) + ε j , (for sales groupj)

Note that at the salesperson level, SRCSP is the salesperson’s SRC, SEXPSP is the salesperson’s sales experience with the company, PKNOWSP is the salesperson’s product knowledge, and SRCCSP is the central salesperson’strategy role commitment. At the sales manager level, SRCSM is the sales manager’s strategy role commitment, DCSM is the sales manager’s degree centrality, WEXPSM is the sales manager’s work experience with the company, TAL is the sales manager’s transactional leadership, TFL is the sales manager’s transformational leadership. At the sales group level, ECSG is sales group’s external connectivity, and SPSG is the sales group’s sales performance.

Results

Measurement model

Although all the scales in this study were either adapted or developed from previously tested measures in the literature, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis to validate the scales. Results showed that all items loaded on their corresponding factors. An additional confirmatory factor analysis on focal constructs also resulted in acceptable fit indexes (χ2 = 48.6, d.f. =28; comparative fit index = .96; Tucker–Lewis index = .93). Item loadings are reported in the Appendix.

As Table 3 shows, all the constructs have composite reliabilities greater than .90, and all the AVEs exceed .50. These results indicate that our measures are highly reliable. Moreover, because the AVE values for all constructs exceeded the squared correlations between each respective pair, the constructs also exhibited discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker 1981). Since we collected data from salespeople regarding the transactional and transformational leadership styles of their sales managers, we ran a few tests to evaluate the appropriate level of aggregation for these measures in the HLM model. After analyzing the intraclass correlations, we found support for the aggregation of data to the sales manager level (Transactional Leadership: ICC1 = .25, ICC2 = .81, Rwg = .75; Transformational Leadership: ICC1 = .23, ICC2 = .83; Rwg = .73). ICC1 represents the proportion of overall variance that resides within versus between groups. ICC1 for the leadership measures indicated that more than 75% of the overall variance resided between sales managers rather than between salespeople within each manager, suggesting that our leadership measures should be aggregated to the manager level (K. J. Klein et al., 2000). Similarly, ICC2 indicates group mean reliability, and values above .7 pass the recommended threshold for aggregation (K. J. Klein et al., 2000). Finally, the median Rwg for both variables is above the recommended threshold for aggregation (K. J. Klein et al., 2000).

Hypotheses testing

Main effects

Table 4 reports the estimation results of Model 1 (HLM regression), and Table 5 presents the results of Model 2 (OLS regression). In support of H1, we found that sales managers’ transactional leadership has a significant positive effect on salespeople’s strategy role commitment (H1: γ = .24, p < .05). Sales managers’ transformational leadership also has a positive and significant impact on salespeople’s strategy role commitment (H2: γ = .38, p < .05), and its effect is significantly stronger compared to the main effect of transactional leadership (∆γ = .14, p < .05). Moreover, we found support for the main effect of the central salesperson’s strategy role commitment on peer salespeople’s strategy role commitment (H3: γ = .25, p < .05). As a control variable, we also found support for the main effect of sales managers’ strategy role commitment on salespeople’s strategy role commitment (γ = .32, p < .05). Overall, our findings support our hypotheses that both transformational and transactional leadership styles improve salespeople’s strategy role commitment during strategy implementation. In addition, salespeople’s strategy role commitment depends on how committed the central salesperson is to the strategy.

H6 predicts that sales groups in which salespeople are, on average, more committed to a strategy achieve higher levels of sales of new products. To test this hypothesis, we applied an OLS regression of the average (per sales group) sales quota achievement of new products on the average strategy role commitment of salespeople in a sales group. We found strong support for the hypothesized positive relationship (H6: β = .28, p < .05).

Moderation effects

Figure 2 illustrates the hypothesized moderating effects. We found that sales managers’ degree centrality positively moderates the relationship between transformational leadership and salespeople’s strategy role commitment (H2a: γ = .18, p < .05), but it had no effect on the impact of transactional leadership (H1a: γ = .10, p > .05). Thus, sales managers who are more central in their groups are more successful in enhancing their subordinates’ strategy role commitment only when they apply a transformational leadership style. We also found that the impact of the central salesperson’s strategy role commitment on peer salespeople in the group is weaker when the sales group has a high level of external connectivity (H3a: γ = −.17, p < .05). This finding indicates that more diverse sources of work-related information broaden salespeople’s perspectives and, consequently, reduce the influence of central peers.

Moderation effects. Note: At the salesperson level, SRCSP is the salesperson’s strategy role commitment, and SRCCSP is the central salesperson’strategy role commitment. At the sales manager level, DCSM is the sales manager’s degree centrality, TAL is the sales manager’s transactional leadership, TFL is the sales manager’s transformational leadership. At the sales group level, ECSG is sales group’s external connectivity

Consistent with our prediction, we found that the central salesperson’s strategy role commitment positively moderates the relationship between sales managers’ transformational leadership and salespeople’s strategy role commitment (H4: γ = .29, p < .05). This finding implies that using a transformational leadership style by sales managers during strategy implementation is less effective if the central salesperson in the group is not committed to the strategy. In addition, we found that sales managers’ transactional leadership negatively moderates the impact of the central salesperson’s strategy role commitment on peers (H4: γ = −.16, p < .05). Thus, when the sales manager practices a transactional leadership style during new strategy implementation, the central salesperson will have a weaker effect on peers.

Control variables

Our results reveal that average salespeople’s sales experience (β = .14, p < .05) and sales managers’ work experience (β = .15, p < .05) have positive effects on the sales group’s sales performance. Furthermore, average salespeople’s product knowledge positively affects the sales group’s sales performance (β = .17, p < .05).

Discussion

Recent theories of leadership suggest that leaders are not necessarily the occupants of formal managerial positions but could rather be identified by their network centrality. Our results lend credence to this notion about leadership. We find that, during marketing strategy implementation, formal managers are not the only source of influence on salespeople with regard to strategy role commitment. In addition to them, salespeople with high levels of centrality in social networks can significantly influence peers’ strategy commitment. This peer impact is even stronger when the sales group has low external connectivity, denoted by fewer advice-seeking ties with other groups, which makes the group more dependent on the central salesperson. We contrasted the central salesperson’s influence with the sales manager’s leadership styles to provide a better perspective on the significance of informal versus formal leadership effects in sales groups.

Our results indicate that central salespeople with low strategy role commitment not only directly affect peers’ strategy commitment, but also undermine the effect of formal managers’ transformational leadership on salespeople. Transformational leaders often attempt to internally motivate followers by depicting a desired vision and promoting higher-level shared goals. However, these distal goals might be generic and vague and need to be translated into practical guidelines and daily workplace knowhow. Thus, salespeople may refer to trusted sources of advice such as central salespeople to make sense of the transformational manager’s guidelines. In this process, non-committed central peers can severely hurt the effect of transformational leadership by contradicting and opposing the transformational manager’s perspectives. Instead, transactional leadership, which works through compliance rather than internal motivation, lessens the impact of non-committed central salespeople on peers. Salespeople prefer to follow the clear guidelines and incentive system of the transactional manager in order to secure rewards and avoid punishment, rather than following a riskier source of advice such as central salespeople. Thus, transactional leadership substitutes the peer impact of central salespeople.

We also show that sales managers with higher degree centrality can more effectively use transformational leadership, although we did not find significant moderation of managers’ centrality on the effect of transactional leadership. Since transactional leaders set clear expectations with contingent reward and punishment, they might not need the support of a strong informal network (i.e., degree centrality) to align subordinates with their objectives. In contrast, transformational leadership is broader and less explicit. Thus, strong social ties with subordinates will help transformational leaders to combine their formal inspirational speeches with informal advice.

Theoretical implications

Leadership research in sales management

Drawing from recently developed social network perspectives of leadership, we challenge the extant views of leadership as a top-down, action-oriented phenomenon limited to managers. Current leadership research in sales management also relies on the traditional views of leadership as supervisory behaviors (see Table 1 for a review). Instead, we define leadership as a relational phenomenon that involves building and using social capital. This view of leadership expands the definition of leader to anyone in the organization who possesses high centrality, allowing researchers to more flexibly study interpersonal influence in the organizations. In addition, we extend the literature even further by contrasting the relational view of leadership with the behavioral one. We demonstrate that managerial behaviors and the influence of informal leaders affect one another. While informal leaders can undermine managers’ transformational behaviors, transactional behaviors could circumvent the relational influence of central salespeople.

These findings also contribute to prior literature on transformational and transactional styles in two ways. First, while prior research has mostly focused on the advantageous effects of transformational leadership, our results propose an important contingency for its positive impact. Second, the extant research on leadership styles mostly concludes that transformational leadership dominates the transactional style. We extend this line of research by showing that the balance tips in favor of transactional leadership when central salespeople are not committed to the new strategy. Our findings also reveal whether relational ties are needed for specific leadership styles to be effective. Transformational leadership influences through internalization and intrinsic motivation (MacKenzie et al., 2001). Our findings suggest that in order to influence via intrinsic motivation, managers need to have network centrality among their followers. In other words, delivering transformational speeches without being accessible for everyday work-related advice can result in losing impact to those informal leaders whose influence is driven from daily interactions with peers. On the other hand, influence through transactional leadership does not require strong relational ties with subordinates or high manager’s degree centrality. These findings are novel in the way that they explain the interrelatedness of behavioral and relational views of leadership.

Marketing strategy implementation

We contribute to this literature stream by demonstrating that, unlike what prior studies assume, strategy execution does not occur in a social vacuum. Future research on strategy implementation could benefit from our novel results by accounting for both formal and informal sources of influence as well as the structure of social ties among the implementers to get a more accurate picture of the implementation process.

Intra-organizational networks

Together our findings offer novel insights into the role of social networks and network centrality in organizations. Our results add a new perspective of centrality in organizational networks in which centrality is viewed not only as a valuable asset for the central salesperson, but also as a source of influence on peers. Our results suggest that similar to consumer markets where central influencers and opinion leaders have a direct impact on the adoption of new products (Van den Bulte and Wuyts 2007), central employees play an integral role in the internal marketing of new strategies. This role could rival managerial influence and result in unwanted ramifications regarding the commitment of the sales force to the new strategy. However, unlike the consumer markets where changing the influence of central consumers might not be feasible, the informal influence of central peers could be reduced if managers used certain strategies such as transactional leadership or network engineering, as we discuss in more detail below.

Managerial implications

During a marketing strategy implementation process, one of the major goals of managers is to motivate their subordinates and obtain their commitment to the firm’s strategic initiatives. Our findings offer actionable guidelines to managers.

First, sales managers need to evaluate the existence, degree of influence, and work attitudes and behaviors of central salespeople in their sales groups. Social network literature recommends a list of antecedents to centrality in groups such as personality and demographics variables (Klein et al. 2000). These antecedents may guide managers in identifying central salespeople in their groups. However, we suggest that, in a small group context, managers can also directly ask their subordinates about their regular sources of work-related advice. Managers can use this data to identify central players in their groups and to also evaluate external versus internal sources of advice for their employees. This analysis helps managers in applying the right balance of leadership styles and devising effective strategies to influence their employees.

Second, sales managers need to apply a mix of transformational and transactional leadership styles in order to obtain the commitment of their salespeople to a new strategy. We suggest that choosing the right balance of leadership styles depends on the patterns of social networks in the sales group. Managers need to observe and evaluate their own social networks in the group, social networks of the most central salesperson in the sales group, and social networks of the entire sales group as a business unit in order to regulate their leadership style accordingly.

Third, a sales manager may face serious challenges in strategy implementation when the central salesperson in the group in not supportive of the new strategy and has a low strategy role commitment. Managers can use a variety of methods to reduce or nullify the negative peer effects of non-committed central salespeople. From a leadership perspective, we suggest that applying a transactional leadership style significantly reduces the destructive peer effects of central salespeople. From a social network perspective, enhancing the external connectivity of the sales group through expanding its external network ties, as well as strengthening the centrality of the sales manager in his group, will lessen the peer effects of the central salesperson. It should be noted that building or modifying social network patterns is a long-term process and do not immediately occur following a managerial decision. Thus, sales managers need to plan reasonably ahead of the strategy implementation period to modify and align the social networks of their groups for the successful implementation of the strategy.

Limitations and future research

We conclude by acknowledging the limitations of our research and suggesting directions for future research. First, our data was limited to sales managers who worked directly with salespeople. Future research should look into contexts where multiple layers of management are involved in the execution of the strategy in order to evaluate whether the importance of managers’ centrality, as well as the effects of their leadership styles, would be different across different levels (e.g., CMO vs. district manager vs. regional sales manager). Second, although we surmise that our findings will hold in most new strategy implementation contexts that involve uncertainty and change, future research could verify this conjecture by studying other types of strategies such as market development, customer service plans, and customer engagement programs. Third, further research could examine whether social networks or commitments change during longer-term strategy implementation processes or address other longitudinal questions that our cross-sectional data might not be able to tap into. Fourth, sales groups are not isolated and social networks may exist between sales groups and other organizational functions such as marketing, engineering, and manufacturing. Investigating the role of such networks during strategy implementation would be another interesting direction for future research.

Moreover, we only examined the consequences of social networks during strategy implementation. Further research is necessary to understand how informal social networks develop or decay in sales organizations and what sales managers can do to build effective network structures inside their sales force. Furthermore, it would be useful to examine how individual attributes of salespeople interact with social network patterns to affect individual, group, and organizational outcomes. Finally, we collected data from a single firm. Future research should compare strategies implemented in different firms to see if firm characteristics (e.g., company culture, firm size, centralization, number of managerial levels) could influence the importance of social networks in leadership.

Notes

We thank the AE for asking for the alternative of these two leadership styles.

References

Ahearne, M., Lam, S. K., Mathieu, J. E., & Bolander, W. (2010a). Why are some salespeople better at adapting to organizational change? Journal of Marketing, 74(May), 65–79.

Ahearne, M., Rapp, A., Hughes, D. E., & Jindal, R. (2010b). Managing sales force product perceptions and control systems in the success of new product introductions. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(August), 764–776.

Ahearne, M., Lam, S. K., & Kraus, F. (2014). Performance impact of middle managers' adaptive strategy implementation: The role of social capital. Strategic Management Journal, 35(1), 68–87.

Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Weber, T. J. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual review of psychology, 60, 421–449.

Balkundi, P., & Kilduff, M. (2006). The ties that lead: A social network approach to leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(4), 419–439.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations: Free Press; Collier Macmillan.

Behrman, D. N., & Perreault, W. D. J. (1982). Measuring the performance of industrial salespersons. Journal of Business Research, 10(3), 355–370.

Boichuk, J. P., Bolander, W., Hall, Z. R., Ahearne, M., Zahn, W. J., & Nieves, M. (2014). Learned helplessness among newly hired salespeople and the influence of leadership. Journal of Marketing, 78(1), 95–111.

Bolander, W., Satornino, C. B., Hughes, D. E., & Ferris, G. R. (2015). Social networks within sales organizations: Their development and importance for salesperson performance. Journal of Marketing, 79(6), 1–16.

Bonoma, T. V. (1984). Making your marketing strategy work. Harvard Business Review, 62(March/April), 69–76.

Borgatti, S. P. (2005). Centrality and network flow. Social Networks, 27(1), 55–71.

Borgatti, S. P., & Foster, P. C. (2003). The network paradigm in organizational research: A review and typology. Journal of Management, 29(6), 991–1013.

Brass, D. J. (1984). Being in the right place: A structural analysis of individual influence in an organization. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29(December), 518–539.

Brass, D. J. (2011). A social network perspective on industrial/organizational psychology. In S. W. J. Kozlowski (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of organizational psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brass, D. J., Galaskiewicz, J., Greve, H. R., & Tsai, W. (2004). Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 47(6), 795–817.

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The social structure of competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Burt, R. S. (2000). The network structure of social capital. Research in Organizational Behavior, 22, 345–423.

Carter, D. R., DeChurch, L. A., Braun, M. T., & Contractor, N. S. (2015). Social network approaches to leadership: An integrative conceptual review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 597.

Chiaburu, D. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2008). Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1082–1103.

Chimhanzi, J., & Morgan, R. E. (2005). Explanations from the marketing/human resources dyad for marketing strategy implementation effectiveness in service firms. Journal of Business Research, 58(6), 787–796.

Choi, J. N. (2002). External activities and team effectiveness review and theoretical development. Small Group Research, 33(2), 181–208.

Deichmann, D., & Stam, D. (2015). Leveraging transformational and transactional leadership to cultivate the generation of organization-focused ideas. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 204–219.

Dess, G. G., & Origer, N. K. (1987). Environment, structure, and consensus in strategy formulation: A conceptual integration. Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 313–330.

Duclos, P., Luzardo, R., & Mirza, Y. H. (2007). Refocusing the sales force to cross-sell. The McKinsey Quarterly, 7, 1–4.

Enders, C. K., & Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods, 12(2), 121.

Flaherty, K., Lam, S. K., Lee, N., Mulki, J. P., & Dixon, A. L. (2012). Social network theory and the sales manager role: Engineering the right relationship flows. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 32(1), 29–40.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50.

Fuller, R. (2014). 3 behaviors that drive successful salespeople. Retrieved from http://blogs.hbr.org/2014/08/3-behaviors-that-drive-successful-salespeople/

Gladstein, D. L. (1984). Groups in context: A model of task group effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29(December), 499–517.

Gonzalez, G. R., Claro, D. P., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Synergistic effects of relationship managers' social networks on sales performance. Journal of Marketing, 78(January), 76–94.

Grant, A. M. (2012). Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 458–476.

Guzzo, R. A., & Dickson, M. W. (1996). Teams in organizations: Recent research on performance and effectiveness. In J. T. Spence & J. M. Darley (Eds.), Annual review of psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 307–338). Palo Alto: Annual Reviews.

Hinterhuber, A., & Liozu, S. (2012). Is it time to rethink your pricing strategy? MIT Sloan Management Review, 53(Summer), 69–77.

Ibarra, H. (1993). Personal networks of women and minorities in management: A conceptual framework. Academy of Management Review, 18(1), 56–87.

Jaworski, B. J., & Kohli, A. K. (1991). Supervisory feedback: Alternative types and their impact on salespeople's performance and satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(May), 190–201.

Kilduff, M., & Brass, D. J. (2010). Organizational social network research: Core ideas and key debates. The Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 317–357.

Klein, H. J., Wesson, M. J., Hollenbeck, J. R., & Alge, B. J. (1999). Goal commitment and the goal-setting process: Conceptual clarification and empirical synthesis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(6), 885.

Klein, K. J., Bliese, P. D., Kozlowski, S. W. J., Dansereau, F., Gavin, M. B., Griffin, M. A., et al. (2000). Multilevel analytical techniques: Commonalities, differences, and continuing questions. In K. J. Klein & S. W. J. Kozlowski (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kohli, A. K. (1985). Some unexplored supervisory behaviors and their influence on salespeople’s role clarity, specific self-esteem, job satisfaction, and motivation. Journal of Marketing Research, 22(4), 424–433.

Kohli, A. (1989). Effects of supervisory behavior: The role of individual differences among salespeople. Journal of Marketing, 53(4), 40–50.

Krackhardt, D., & Stern, R. N. (1988). Informal networks and organizational crises: An experimental simulation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51(2), 123-140.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Rich, G. A. (2001). Transformational and transactional leadership and salesperson performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(2), 115–134.