Abstract

Summary

The challenges of hip fracture care in Malaysia is scarcely discussed. This study evaluated the outcomes of older patients with hip fracture admitted to a teaching hospital in Malaysia. We found that one in five individuals was no longer alive at one year after surgery. Three out of five patients did not recover to their pre-fracture mobility status 6 months following hip fracture surgery.

Purpose

With the rising number of older people in Malaysia, it is envisaged that the number of fragility hip fractures would also increase. The objective of this study was to determine patient characteristics and long-term outcomes of hip fracture in older individuals at a teaching hospital in Malaysia.

Methods

This was a prospective observational study which included consecutive patients aged ≥ 65 years old admitted to the orthopedic ward with acute hip fractures between March 2016 and August 2018. Patient socio-demographic details, comorbidities, pre-fracture mobility status, fracture type, operation and anesthesia procedure, and length of stay were recorded. Post-fracture mobility status was identified at 6 months. Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to assess the risk of death in all patients.

Results

310 patients (70% women) with the mean age of 79.89 years (SD 7.24) were recruited during the study period. Of these, 284 patients (91.6%) underwent surgical intervention with a median time to surgery of 5 days (IQR 3–8) days. 60.4% of patients who underwent hip fracture surgery did not recover to their pre-fracture mobility status. One year mortality rate was 20.1% post hip fracture surgery. The independent predictor of mortality included advanced age (hazard ratio, HR = 1.05, 95% CI = 1.01–1.08; p = 0.01), dependency on activities of daily living (HR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.26–3.45; p = 0.01), and longer length of hospitalization (HR = 1.02, 95% CI = 1.01–1.04; p < 0.01).

Conclusion

One in 5 individuals who underwent hip fracture surgery at a teaching hospital in Kuala Lumpur was no longer alive at one year. A systematic approach to hip fracture management is crucial to improve outcomes and restore pre-fracture function of this vulnerable group of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence of hip fracture is increasing exponentially in the Asia Pacific region with an estimated increase of 1.12 million in 2018 to 2.56 million by 2050 [1]. Malaysia is projected to have the highest rate of increase in hip fracture injuries by 2050. Although international guidelines proposed a seamless approach to the management of hip fracture among older adults, replicating the same standards in Malaysia is highly challenging due to discrepancies in cultural beliefs, lower health literacy, and healthcare funding provision for older adults [2].

In Malaysia, a majority of older hip fracture patients are managed by the orthopedic team with limited orthogeriatric input due to the scarcity of geriatricians in the country [3, 4]. The length of time to surgical intervention varies, depending on whether the public or private system is used. In public hospitals, the average waiting time is around 5 days to 2 weeks while the private sector provides much faster access to surgery within a few days. The hip implants for hemiarthroplasty have to be paid for before surgery in both sectors. Private healthcare for older adults is therefore entirely out-of-pocket as most older adults do not have private health insurance coverage. Care at public hospitals is funded fully by taxation, where patients only need to pay nominal fees in this heavily subsidized public sector. As a result, in the case of hip surgery, the operation cost is fully borne by the tax payer but the patient is required to pay for the implant. The full cost of private healthcare and supplemental cost for public healthcare for our older population is usually borne by adult children, as few older adults have any income or savings. While implants are eventually paid for by a welfare fund for patients who could not afford the cost, the protracted application process inevitably leads to long delays.

Despite the projected increase in number of older persons with hip fractures, studies on the long-term outcomes for hip fracture in Malaysia remain limited. Our study is aimed at identifying the characteristics and long-term outcomes of older patients admitted with acute hip fracture in a teaching hospital in Malaysia. A better understanding of the clinical burden, management, and outcomes of older adults with hip fracture is needed in order to improve the care of this vulnerable group of individuals.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a prospective observational study performed in University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), a 1000-bedded teaching hospital in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. UMMC is a government-funded public medical institution offering subsidized care. A proportion of the patients are government pensioners for whom all charges, including hospitalization and procedural fees as well as hip implants, are borne by their pension fund.

Consecutive patients aged 65 years and above who sustained an acute hip fracture between 22 March 2016 and 31 August 2018 were recruited into the study. Informed consent was obtained from patients or their next-of-kin for the conduct of this study. Patients with hip fracture were admitted to the orthopedic trauma ward with routine geriatric consultation on weekdays, from 8am to 5 pm. Geriatricians provide preoperative assessment, optimization of medical conditions, postoperative prevention of complications, and initiation of antiosteoporosis medication. Hip fractures were defined as all fractures from the femoral neck to subtrochanteric regions. Patients with pathological hip fracture, periprosthetic fracture, fractures associated with high-energy injury, and polytrauma were excluded. This study was approved by the University Malaya Medical Centre Ethics Committee Board (20,163–2260).

Data collected included patient baseline socio-demographics, pre-fracture residence, pre-fracture mobility status, and performance of activities of daily living (ADL) such as bathing, feeding, grooming, and toileting. Pre-fracture mobility status was recorded as independent walking without aid, walking with one aid, use of walking frame, or chairbound/bedbound. Ability to perform ADL was further dichotomized to independent or dependent on others (requiring assistance in one or more ADL) for the purpose of analysis. The comorbidities recorded in this study were self-reported, physician-diagnosed conditions of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, stroke, osteoporosis, and dementia. The diagnosis of ischemic heart disease included patients with previous history of angina and coronary artery disease. The presence of lung disease included the presence of the diagnosis of asthma, obstructive airway disease, lung fibrosis, and bronchiectasis. Details of fracture type and reason for non-operative decision in patients who were managed conservatively were documented. For patients who underwent surgical intervention for hip fracture, waiting time to surgery (defined as time of admission to time of surgery), type of surgical and anesthesia procedure were recorded. Patients who were transferred out of bed within 24 h postoperatively were classified as having early mobilization. Length of hospitalization and inpatient mortality were also determined.

Outcome measures

Patients or their next of kin were contacted via telephone consultation at 6 months to determine their post-fracture mobility and residence status. For patients who underwent hip surgery, differences between their pre-fracture and post-fracture mobility measured at six months were recorded. A decline in mobility from their pre-fracture ability was categorized as poor mobility recovery from fracture incident. Vital status at one year post discharge was obtained from the national death registry department. Mortality data was collected up to 15 October 2019.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean with standard deviation (SD) for parametric data or median with interquartile ranges (IQR) for non-parametric continuous data. Categorical data was presented as frequencies with percentages in parenthesis and compared with the chi-squared test. The Mann–Whitney \(U\) test was employed to determine differences in rating scores, which were considered continuous data. A probability value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significance. A survival curve was first obtained to estimate mortality risk for individuals who underwent hip fracture surgery via the Kaplan–Meier method. Additional adjusted curves were plotted for risk factors that were associated with death following surgery. Cox proportional hazards analyses adjusted for all confounding factors was utilized to determine the hazard ratio for mortality. All predictor variables with a p value of < 0.10 were entered into the proportional hazard model to identify independent factors associated with mortality in our patient group. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

A total of 326 patients met the inclusion criteria during the study period. Of those, 310 patients with completed hospital admission data were included in the analysis of the study (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The median time from fall incident to hospital admission was 1 (IQR = 0–2) day, whereas 4 patients reported no falls leading to the fracture episode.

Two hundred and eighty-four (91.6%) patients underwent surgical intervention for hip fracture, and 26 (8.4%) patients did not undergo hip surgery. Reasons for not operating included refusal by families and/or patients (n = 19), severe acute medical illness (n = 3), and death (n = 4). The median time from hospital admission to surgery was 5 (IQR 3–8) days, with 18% of patients operated within 48 h of admission to hospital. Twenty-seven patients (9.5%) who had financial difficulties paying for their hip implants which required assistance from either the social welfare department or donations from non-government organizations were operated within 7 (IQR 4–10) days from hospital admission. Details of type of surgery and anesthesia are reported in Table 2. Of the patients who underwent hip surgery, 114 (40.1%) patients received early mobilization within 24 h, postoperatively. The median length of hospitalization was 9 (IQR 7–15) days with discharges occurring within a median of 4 (IQR 3–6) days, postoperatively. The reported inpatient mortality following hip fracture surgery was 10/284 (3.5%). Of patients who survived hip fracture surgery, 224/274 (81.8%) of patients were discharged to their own homes, 35/274 (12.8%) to institutionalized care, and 6/274 (2.2%) to a rehabilitation center. 14 (5.4%) patients who were community dwellers were discharged to a care institution after their hip surgery.

All survivors to discharge were contacted via telephone at 6 months. 38 patients had died, and 19 (6.9%) were lost to follow-up. Of the 217 (93.1%) patients with successful follow up telephone call, 131 (60.4%) patients did not recover to their pre-fracture mobility status. The largest decline were from patients who were independently mobile without aid prior to hip fracture (Fig. 2). 77 (35.5%) of patients required the use of walking frames at 6 months following hip fracture surgery. Among patients who were managed conservatively for hip fracture, 6/11 (54.5%) remained chairbound/bedbound at six months post discharge. Overall, 91.2% were living in their own homes, and 8.8% were in institutional care.

The 1 year mortality rates for patients post hip fracture surgery was 20.1% with median follow-up period of 27.5 (IQR 12–35) months for all patients. From the unadjusted Cox proportional hazard analysis for patients who underwent hip surgery, age, men, ADL dependency, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, total number of comorbidities, intertrochanteric fracture, regional anesthesia, and length of hospitalization were significantly associated with mortality (Table 2). Ten factors with p value ≤ 0.10 were entered into the final model to determine the best predictor model for mortality. From this, age, ADL dependence, and length of hospitalization appeared as independent predictors of mortality following hip fracture surgery in older adults (Fig. 3). For patients with hip fracture who were managed conservatively, the 1 year mortality rate was 73.1%.

Discussion

One in five individuals who underwent surgery for hip fracture at a teaching hospital in Kuala Lumpur was no longer alive at 1 year follow-up. Furthermore, a reduction in mobility was observed in three out of five individuals. Overall, the outcome characteristics of patients presenting with hip fractures in our study were comparable with other countries [5]. Those who sustained a hip fracture were primarily community-dwelling and functionally independent. Only a small percentage had a previous diagnosis of osteoporosis [6, 7].

Non-surgical management of hip fracture is still prevalent in Asian countries, mostly due to perceived high risk of surgical death within the perioperative period and the reluctance of patients themselves or their family members for patients to undergo surgery [8,9,10,11]. A systematic review by Loggers et al. reported that one-third of non-operative management of hip fractures were due to non-medical reasons such as declination of surgery, economic reasons, and proxy preferences [12]. Our study, however, found that non-operative management were mainly due to family or patient refusal. While this discrepancy may have emanated from the low expectation of functional recovery and quality of life from the sequelae of severe illness by the Asian older adult and their family members which may have led to the acceptance of the morbidity associated with non-operated hip fractures. Such decisions were possibly made without the adequate knowledge of the potential consequences of not having an operation. Even in frail older patients with functional disabilities, severe cognitive impairment, and multimorbidities, which were associated with poor prognosis following hip fracture injuries, considerations for non-surgical treatment had to be balanced with the risk of pain, complications, and mortality [13, 14].

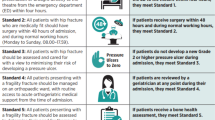

Our study revealed that most patients with hip fracture waited for more than 48 h for their hip surgery. Delay in time to surgery was also found in single-center studies from other lower and middle income countries in the Asia Pacific region, including Thailand, Myanmar, and India, which did not achieve international hip fracture clinical practice standards of having surgery by 48 h of admission to hospital [15,16,17,18,19]. The use of hip fracture clinical care pathways has been shown to address concerns regarding clinical management and optimization of patients prior to surgery, thus reducing delay to surgery. However, challenges specific to lower and middle income countries in the Asia Pacific region which involve delays in informed consent from family members and/or patients, burden of out-of-pocket expenditure for hip implants and surgical cost, lack of prioritization of older adults with hip fracture, and poor coordination of care are among patient and system factors were associated with delays to surgery [20]. Hence, country-specific adjustment is necessary to address the different health care systems and policies across countries and regions in order to improve hip fracture care.

For patients who underwent hip fracture surgery in our study, higher 1-year mortality rates were consistent with the widely recognized observations seen in patients who were older, higher level of dependency, and longer length of hospitalization. As there were limited step-down care facilities, rehabilitation centers, and shortage of public hospital beds in Malaysia, patients were promptly discharged on average at day 4 post-surgery with limited access to continued rehabilitation. Patients were either discharged home, with any care needs met by informal family caregivers or formal salaried caregivers, or directly to residential long term care. Hence, the longer duration of hospitalization in our study may represent patients who had increased comorbidity burden and complications that occurred during hospitalization which subsequently increases mortality risk. Indeed, the length of stay was primarily dictated by time to surgery with the median length of stay postoperatively being only four days compared to a median time to surgery of five days.

Hip fracture in older adults leads to pronounced functional decline and loss of mobility, particularly in individuals with cognitive impairment and poor pre-fracture ambulatory ability [21]. Recovery after hip fracture surgery has been associated with multiple factors starting from the time of injury through to post-discharge care. Studies have shown that early hip fracture surgery by 48 h, early mobilization within 36 h postoperatively, and multidisciplinary rehabilitation helped to improve mobility status and reduce institutionalization rates [22,23,24]. Despite surgical intervention, more than 50% of patients in our study did not regain their pre-fracture level of mobility at 6 months, with a majority of patients declining to requiring the use of a walking frame. Follow-up attendance of outpatient rehabilitation services needed to be initiated on discharge. Many of those who may benefit did not receive it due to lack of referral to community-based rehabilitation services. The delivery of seamless, integrated care beyond acute hip fracture care in hospital remains an aspiration as it is not supported by the current system.

While this was a single-center study and hence may not reflect hip fracture care throughout Malaysia, this study provides a glimpse on the potential differences and deficits in hip fracture care within an upper-middle income nation in South-east Asia. Furthermore, reasons for delay in time to surgery and cause of death in patients after discharge from hospital were not identified in the study. Hence, it is not possible to elucidate if patients with delayed surgery were requiring more time for medical optimization which subsequently led to higher risk of mortality, and this should be considered in a future study which should be extended to multiple centers within Malaysia. Interventions which could reduce time to surgery, improve discharge outcomes, and reduce declination rates for surgery should now be developed as a matter of priority to reduce the burden of hip fracture-related disability in a region with a rapidly aging population.

Conclusion

One in 5 individuals who underwent hip fracture surgery at a teaching hospital in Kuala Lumpur was no longer alive at 1 year. Factors associated with higher mortality following hip fracture surgery include advanced age, functional dependency, and longer length of hospitalization. For patients who survived hip fracture surgery, 60.1% experienced a decline in mobility status. The higher rates of refusal of surgical treatment and longer time-to-surgery observed in this study should be addressed with culturally appropriate intervention strategies as a matter of urgency to reduce the burden of hip fracture related disability in a rapidly aging population.

References

Cheung CL, Ang SB, Chadha M, Chow ES, Chung YS, Hew FL et al (2018) An updated hip fracture projection in Asia: the Asian Federation of Osteoporosis Societies study. Osteoporos Sarcopenia 4(1):16–21

Jaafar N, Perialathan K, Krishnan M, Juatan N, Ahmad M, Mien TYS et al (2021) Malaysian health literacy: scorecard performance from a national survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(11):5813

Ong T, Khor HM, Kumar CS, Singh S, Chong E, Ganthel K et al (2020) The current and future challenges of hip fracture management in Malaysia. Malays Orthop J 14(3):16–21

Tan MP, Kamaruzzaman SB, Poi PJH (2018) An analysis of geriatric medicine in Malaysia-riding the wave of political change. Geriatrics (Basel) 3(4):80

Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF (2019) Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture - a systematic review. World J Orthop 10(3):166–175

Chan CY, Subramaniam S, Mohamed N, Ima-Nirwana S, Muhammad N, Fairus A et al (2020) Determinants of bone health status in a multi-ethnic population in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(2):384

Abdullah MAH, Abdullah AT, (Eds). (2010) National Orthopaedic Registry of Malaysia (NORM). In: Annual report of National Orthopaedic Registry Malaysia (NORM) hip fracture. Jointly published by the National Orthopedic Registry of Malaysia (NORM) and the Clinical Research Centre (CRC), Ministry of Health Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, p 35

Tay E (2016) Hip fractures in the elderly: operative versus nonoperative management. Singapore Med J 57(4):178–181

Yoon BH, Baek JH, Kim MK, Lee YK, Ha YC, Koo KH (2013) Poor prognosis in elderly patients who refused surgery because of economic burden and medical problem after hip fracture. J Korean Med Sci 28(9):1378–1381

Lim WX, Kwek EBK (2018) Outcomes of an accelerated nonsurgical management protocol for hip fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 26(3):2309499018803408

Kawaji H, Uematsu T, Oba R, Takai S (2016) Conservative treatment for fracture of the proximal femur with complications. J Nippon Med Sch 83(1):2–5

Loggers SAI, Van Lieshout EMM, Joosse P, Verhofstad MHJ, Willems HC (2020) Prognosis of nonoperative treatment in elderly patients with a hip fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 51(11):2407–2413

Frenkel Rutenberg T, Assaly A, Vitenberg M, Shemesh S, Burg A, Haviv B et al (2019) Outcome of non-surgical treatment of proximal femur fractures in the fragile elderly population. Injury 50(7):1347–1352

Kim SJ, Park HS, Lee DW (2020) Outcome of nonoperative treatment for hip fractures in elderly patients: a systematic review of recent literature. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 28(2):2309499020936848

Daraphongsataporn N, Saloa S, Sriruanthong K, Philawuth N, Waiwattana K, Chonyuen P et al (2020) One-year mortality rate after fragility hip fractures and associated risk in Nan. Thailand Osteoporos Sarcopenia 6(2):65–70

Rath S, Yadav L, Tewari A, Chantler T, Woodward M, Kotwal P et al (2017) Management of older adults with hip fractures in India: a mixed methods study of current practice, barriers and facilitators, with recommendations to improve care pathways. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):55

Hlaing WY, Thosingha O, Chanruangvanich W (2020) Health-related quality of life and its determinants among patients with hip fracture after surgery in Myanmar. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 37:100752

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (2011) Clinical guideline 124. The management of hip fracture in adults. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13489/54918/54918.pdf. Accessed 10 May 2022

Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) Steering Group (2014) Australian and New Zealand Guideline for hip fracture care: improving outcomes in hip fracture management of adults. Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry Steering Group, Sydney

Armstrong E, Yin X, Razee H, Pham CV, Sa-Ngasoongsong P, Tabu I et al (2022) Exploring barriers to, and enablers of, evidence-informed hip fracture care in five low-middle-income countries: China. Thailand, the Philippines and Vietnam. Health Policy Plan, India

Araiza-Nava B, Mendez-Sanchez L, Clark P, Peralta-Pedrero ML, Javaid MK, Calo M et al (2022) Short- and long-term prognostic factors associated with functional recovery in elderly patients with hip fracture: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int 33(7):1429–1444

Sheehan KJ, Goubar A, Martin FC, Potter C, Jones GD, Sackley C et al (2021) Discharge after hip fracture surgery in relation to mobilisation timing by patient characteristics: linked secondary analysis of the UK National Hip Fracture Database. BMC Geriatr 21(1):694

Handoll HH, Cameron ID, Mak JC, Panagoda CE, Finnegan TP (2021) Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for older people with hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 11:CD007125

Sallehuddin H, Ong T (2021) Get up and get moving-early mobilisation after hip fracture surgery. Age Ageing 50(2):356–357

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to our research assistants Aun Yi Yang and Laila Bilqish for assisting in the data collection.

Funding

The study was funded by the University of Malaya Bantuan Kecil Penyelidikan (BK022-2016) research grant.

All authors declare that the manuscript has not been submitted to other journals for consideration of publication. The manuscript has also not been published previously.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or their next of kin included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Khor, H.M., Tan, M.P., Kumar, C.S. et al. Mobility and mortality outcomes among older individuals with hip fractures at a teaching hospital in Malaysia. Arch Osteoporos 17, 151 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-022-01183-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-022-01183-w