Abstract

Summary

We aim to investigate the nationwide prevalence of asymptomatic radiographic vertebral fracture in Thailand. We found 29% of postmenopausal women had at least one radiographic vertebral fracture. The prevalence was significantly higher among women with osteoporosis at the total hip (TH) region which implies that TH bone mineral density is a determinant of vertebral fracture risk.

Introduction

Radiographic vertebral fracture is associated with an increased risk of osteoporotic fracture and mortality in postmenopausal women. We designed a study to determine the prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures in postmenopausal Thai women.

Methods

The study was designed as a cross-sectional investigation at five university hospitals so as to achieve representation of the four main regions of Thailand. Radiographs were taken from 1062 postmenopausal women averaging 60 years of age. The presence of vertebral fracture was assessed by the Genant’s semiquantitative method with three independent radiologists. Respective bone mineral density was measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) at the lumbar spine (LS), femoral neck (FN), and total hip (TH).

Results

Among the 1062 women, 311 were found to have at least one radiographic vertebral fracture—yielding a prevalence of 29% (95% CI 23.6–32.0%)—and 90 (8.5%, 95% CI 6.8–10.2%) had at least two fractures. The prevalence of vertebral fracture increased with advancing age. Most fractures occurred at one vertebra (71%) and only 29% at multiple vertebrae. The prevalence of vertebral fracture was significantly higher among women with osteoporosis compared with non-osteoporosis at the TH region. There was no significant difference in the prevalence among women with or without osteoporosis at the LS or FN.

Conclusions

Radiographic vertebral fractures were common among Thai postmenopausal women (~ 29%). These findings suggest that approximately one in three postmenopausal women has undiagnosed vertebral fracture. Radiographic diagnosis should therefore be an essential investigation for identifying and confirming the presence of vertebral fractures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a chronic disease characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of the micro-architecture of the bone tissue, leading to skeletal fragility, predisposing individuals to fractures. Vertebral fracture is one of the classic hallmarks of osteoporosis and the most common type of osteoporotic fracture in both men and women [1, 2]. Indeed, not only clinical vertebral fracture but also asymptomatic radiographic vertebral fractures have clinical implications on subsequent fractures, including morbidity, disability, and increased risk of mortality [3,4,5]. Nevertheless, underdiagnosis of vertebral fracture remains a major public health problem worldwide [6,7,8]; therefore, identification of individuals with a vertebral fracture is essential for giving early intervention to patients at high risk.

The prevalence of radiographic vertebral fracture in postmenopausal Caucasians ranges between 15% and 35% [2]. Although the prevalence of vertebral fracture among Asian populations has not been well-documented, epidemiologic studies from Japan, Vietnam, China [9], and Hong Kong report a prevalence between 5.5 and 30% depending on the method of measurement [10,11,12,13,14,15]. In Thailand, Trivitayaratana et al. reported a respective prevalence in women and men of vertebral fracture in Bangkok of 23% and 26% [16]. Jitapunkul et al. reported that the respective incidence of vertebral fracture in women and men in a cohort of a Bangkok suburb, during a 5-year observation, was 32.1/1000 and 54.5/1000 person per year [17].

Owing to the paucity of any nationwide epidemiologic data on asymptomatic vertebral fracture, we designed a study to estimate the nationwide prevalence of asymptomatic radiographic vertebral fracture using a semiquantitative method among postmenopausal Thais living in the four major regions (the North, the Northeast, the Central Plain, and the South).

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

The current study was a cross-sectional investigation undertaken by five university hospitals in Thailand: two centers from the Central Plain (Chulalongkorn and Phramongkutklao Hospitals, Bangkok), one from the North (Suandok Hospital, Chiang Mai), one from the Northeast (Srinagarind Hospital, Khon Kaen), and one from the South (Prince Songkhlanagarind Hospital, Songkhla). All of these hospitals are tertiary care settings. Postmenopausal women attending the postmenopausal clinic were recruited if interested in participating. We excluded the patients with symptoms such as clinical back pain and historical height loss. We also excluded patients with comorbidities that affect bone health, e.g., previous bone tumors, multiple myeloma, or other hematologic malignancies. Based on a previous estimate of the prevalence of vertebral fracture (~ 20%) with a sampling variability of 5% [18], it was estimated that a sample size of at least 1060 was required for statistical adequacy to estimate the true prevalence of vertebral fracture. The local ethics committee of each of the five universities approved the study and informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the revised 1983 Helsinki Declaration.

BMD measurement

Bone mineral density (BMD) was determined using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) densitometer (2 centers with the Lunar Prodigy model and 3 with the Hologic Discovery model). The densitometers were standardized using the on-board standard phantom prior to the measurement: all of the study sites used this same protocol [19, 20]. The bone density of the lumbar spine (LS), femoral neck (FN), and total hip (TH) of all participants was measured. The coefficient of variation for BMD for normal subjects among centers ranged between 1.5 and 2.0% for LS and 1.3 and 1.5% for FN and TH. Standardized BMD (sBMD) was calculated and presented. Osteoporosis was defined by a T score of less than − 2.5 standard deviation (SD), compared with the peak young adult mean for Thai women [21]. After the data collection phase, the lead author examined the X-rays and patients with any fractured vertebral bodies were excluded from the calculations.

Radiography and vertebral fracture assessment

A lateral thoraco-lumbar (T-L) X-ray radiograph was taken with a 101.6-cm tube-to-film distance—as per standard protocol that included details regarding positioning of the participants and the radiographic technique used. Radiographs were taken in the left lateral position centered at L1 level. There was no difference in imaging acquisition technique in all study sites. Radiographic (morphometric) vertebral fracture (referred to as vertebral fracture in this study) was diagnosed using the Genant’s semiquantitative method by three independent radiologists [22]. All three were well-trained radiologists who have experienced in musculoskeletal imaging interpretation for more than 10 years and were expertise in fracture grading by Genant’s classification. Any difference in the assessment of a joint (among the readers) was resolved by consensus. The kappa coefficient among radiologists was 0.64 (95% CI 0.54–0.76). Vertebral bodies from T4 to L4 levels were assessed to define vertebral fracture in this study.

Statistical analyses

The prevalence of asymptomatic radiographic vertebral fracture and the 95% confidence interval (using Wilson’s score method) [23] were calculated for each age strata. To compare the prevalence of vertebral fracture between the osteoporosis and non-osteoporosis participants, the Chi-squared test was used. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 17.

Results

A total of 1115 postmenopausal women were recruited in the study. After excluded 53 subjects with history of chronic back pain and significant historical height loss, there were 1062 women included for the final analysis. Characteristics of the participants stratified by group are presented in Table 1. The average age for all women was 60 years (range, 36–90). Using the WHO’s criteria, the prevalence of osteoporosis in the entire sample at LS, FN, and TH was 13.7% (145/1061), 15.5% (164/1060), and 4.5% (48/1058), respectively. The prevalence at all sites increased with age.

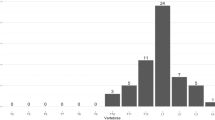

Among the studied women, 311 were found to have at least one radiographic vertebral fracture, yielding a prevalence of 29% of whom 90 (8.5%) had at least two fractures. On average, women with a vertebral fracture were older than women without fracture (61.4 vs. 59.6 years old, p = 0.003); however, there were no significant differences in body weight, height, or BMD between the two groups (Table 1). One, two, and three vertebral fractures were identified in 71%, 26%, and 2.8%, respectively, of the women suffering fracture. The common sites of fracture were T12, (14.8%), T11 (13.1%), and L1 (12.7%). The frequency of 3 grades of fracture was grade 1 (57.4%), grade 2 (22.6%), and grade 3 (20.0%) (Table 2). The prevalence of vertebral fracture increased with advancing age; for instance, the prevalence of fracture in postmenopausal women under 50 years of age was 25% which increased to 33% among those 60 over (Table 3). The prevalence of vertebral fracture in women with osteoporosis at TH was significantly higher than those without osteoporosis (45.8% vs. 28.5%, p = 0.01). There was, nevertheless, no significant difference in the prevalence among women with or without osteoporosis at the LS (33.1% vs. 28.7%, p = 0.163) or FN (30.5% vs. 29.1%, p = 0.395). The prevalence of osteoporosis and vertebral fracture by region of Thailand is presented in Table 4. There was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence among the regions.

Discussion

Vertebral fracture is the most common complication of osteoporosis and yet the real magnitude of the problem is difficult to quantify. More than half of all vertebral fractures are asymptomatic and can go unnoticed. Radiographic diagnosis is used to identify and confirm the presence of vertebral fracture in clinical practice and research setting.

The growing number of elderly people in Thailand has been accompanied by an increase in the incidence of osteoporosis [24]. Vertebral fractures show a particularly high rate of occurrence; thus, it is important to understand the epidemiology of these fractures and to determine their diagnosis and medical treatment. In Thailand, however, few reports have described the prevalence of vertebral fractures [16, 17]. Our study therefore recruited postmenopausal Thai women from the four major regions of the country, namely, the North, the Northeast, the South, and the Central Plain, using Genant’s semiquantitative method to diagnose vertebral fracture(s). A total of 13,806 vertebrae from 1062 participants were analyzed. Unsurprisingly, we found higher prevalence of fracture at the thoracic-lumbar levels (T11-L1). However, the absence of a higher frequency also at the mid-thoracic level is unusual. This suggests a relatively conservative interpretation for mid thoracic wedges by radiologists which warrant caution in extrapolating these findings. The most common grade of fracture in our study was grade 1 (57.4%) according to Genant’s classification which usually present as asymptomatic fracture.

We found that ~ 29% of the participating postmenopausal women had asymptomatic vertebral fractures, which is comparable with that observed among Caucasian populations (25% of women 50 or older in the UK [25] and 20% of women over 65 in a study on osteoporotic fractures [26]) but higher than the 15% of women over 50 in the Latin American Vertebral Osteoporosis Study (LAVOS) [27].

Although the overall (i.e., all age groups) prevalence in our study is comparable with Japanese [10], Vietnamese [12], Taiwanese, and Chinese women [9, 13,14,15]), the age-group prevalence among Thai women under 50 and between 50 and 59 tends to be much higher than among other Asian populations but is similar to other reports on Thai women. The substantial variation in the prevalence of vertebral fracture among populations (and age groups) is probably due to differences in population characteristics, the BMD reference database, genetics, lifestyle patterns, and methods of vertebral fracture assessment [28].

There is no single best method for assessing vertebral fracture [29] and concordance between methods is modest (coefficient ranging between 0.53 and 0.68) [30]. The estimate of the prevalence of radiographic vertebral fracture based on the current study is within the international variability ranges. We also found that the fracture at the lower thoracic spine and upper LS was the most common, which is consistent with other reported observations of Caucasian and Asian populations [25, 26]. We did not, however, assess fracture at the L5 level, which is where previous studies indicated was the most common site of fracture, especially in women.

In our study, we found that only women with osteoporosis at the TH had a significantly higher risk of vertebral fracture, which agrees with the consistent association among the prevalence of TH osteoporosis and vertebral fracture in the various regions. This implies that TH BMD is a better determinant of vertebral fracture risk. However, the prevalence of osteoporosis was low (4.5%) at the TH, with substantially higher based upon either spine LS or femoral neck FN BMD (13.7% at the LS, 15.5% at the FN, respectively). This may be the cause that the relationship of osteoporosis to vertebral fractures was far stronger for the more specific TH than for the LS or FN. The use of BMD in the other sites for fracture risk assessment should be re-evaluated for the sake of cost-effectiveness and pharmacological interventions. Since economic resources are limited, it is prudent to look for robust determinants that closely relate fractures with more serious outcomes. We would then be able to give the most appropriate and cost-effective treatment to high-risk persons.

The previous studies in Thailand regarding prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures were conducted only in Bangkok, which is the capital city of Thailand. The novelty of our study is its nationwide multi-center approach from which our participants were recruited from the four major regions of the country, which increases the study’s external validity. The data were obtained from both rural and urban areas which provide a broadly representative population of Thai postmenopausal women. Moreover, this study examined the prevalence of fracture using semiquantitative measurement by Genant’s classification. Three independent radiologists reviewed and interpreted the radiographs using Genant’s standard method, which is more objective and reproducible (i.e., sensitive) than other qualitative methods [22].

Care should be taken in extrapolating these results to other populations due to the many differences in diet, activity level, and general health among countries. All participants were recruited from tertiary care setting which may lead to a selection bias. An effect from the selection bias may be seen as a very high prevalence rate of vertebral fracture, 25%, in postmenopausal women younger than 50 years of age. In addition, the BMD measurement variability among machines and differences in precision errors also make comparisons among studies difficult. The current study was designed to assess vertebral fracture between the T4 and L4 levels, which are the common sites of osteoporotic fractures. It is possible, however, that not all radiographic fractures found in our study can be attributed to osteoporosis.

In conclusion, radiographic vertebral fractures were quite common among the postmenopausal Thai women in our study (~ 29%), but the prevalence is comparable with Asian and Caucasian populations, using similar semiquantitative methods of measurement. These findings suggest that approximately one in three postmenopausal women in Thailand has undiagnosed vertebral fracture; therefore, radiographic diagnosis should be an essential investigation for identifying and confirming the presence of vertebral fractures.

Limitations

There was a poor association between spine BMD with fracture risk, possibly because fractured vertebral bodies were included in the analysis of spine BMD, resulting in a falsely high BMD value. But in order to correct for this and to have a valid definition for osteoporosis, we used non-fractured levels for the analysis.

References

Melton LJ, Kan SH, Frye MA et al (1989) Epidemiology of vertebral fractures in women. Am J Epidemiol 129:1000–1011. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115204

O’Neill TW, Felsenberg D, Varlow J et al (1996) The prevalence of vertebral deformity in European men and women: the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 11:1010–1018. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650110719

Melton LJ, Atkinson EJ, Cooper C et al (1999) Vertebral fractures predict subsequent fractures. Osteoporos Int 10:214–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980050218

Pongchaiyakul C, Nguyen ND, Jones G, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2005) Asymptomatic vertebral deformity as a major risk factor for subsequent fractures and mortality: a long-term prospective study. J Bone Miner Res 20:1349–1355. https://doi.org/10.1359/JBMR.050317

Burger H, van Daele PL, Algra D et al (1994) Vertebral deformities as predictors of non-vertebral fractures. BMJ 309:991–992. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.309.6960.991

Cooper C, Melton LJ (1992) Vertebral fractures. BMJ 304:793–794. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.304.6830.793

Delmas PD, van de Langerijt L, Watts NB, Eastell R, Genant H, Grauer A, Cahall DL, IMPACT Study Group (2005) Underdiagnosis of vertebral fractures is a worldwide problem: the IMPACT study. J Bone Miner Res 20:557–563. https://doi.org/10.1359/JBMR.041214

Gehlbach SH, Bigelow C, Heimisdottir M, May S, Walker M, Kirkwood JR (2000) Recognition of vertebral fracture in a clinical setting. Osteoporos Int 11:577–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980070078

Ling X, Cummings SR, Mingwei Q, Xihe Z, Xioashu C, Nevitt M, Stone K (2000) Vertebral fractures in Beijing, China: the Beijing Osteoporosis Project. J Bone Miner Res 15:2019–2025. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.10.2019

Ross PD, Fujiwara S, Huang C et al (1995) Vertebral fracture prevalence in women in Hiroshima compared to Caucasians or Japanese in the US. Int J Epidemiol 24:1171–1177. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/24.6.1171

Kitazawa A, Kushida K, Yamazaki K, Inoue T (2001) Prevalence of vertebral fractures in a population-based sample in Japan. J Bone Miner Metab 19:115–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007740170049

Ho-Pham LT, Nguyen ND, Vu BQ, Pham HN, Nguyen TV (2009) Prevalence and risk factors of radiographic vertebral fracture in postmenopausal Vietnamese women. Bone 45:213–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2009.04.199

Lau EM, Chan YH, Chan M et al (2000) Vertebral deformity in Chinese men: prevalence, risk factors, bone mineral density, and body composition measurements. Calcif Tissue Int 66:47–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002230050009

Tsai K, Twu S, Chieng P et al (1996) Prevalence of vertebral fractures in Chinese men and women in urban Taiwanese communities. Calcif Tissue Int 59:249–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002239900118

Lau EM, Chan HH, Woo J et al (1996) Normal ranges for vertebral height ratios and prevalence of vertebral fracture in Hong Kong Chinese: a comparison with American Caucasians. J Bone Miner Res 11:1364–1368. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650110922

Trivitayaratana W, Trivitayaratana P, Bunyaratave N (2005) Quantitative morphometric analysis of vertebral fracture severity in healthy Thai (women and men). J Med Assoc Thail 88(Suppl 5):S1–S7

Jitapunkul S, Thamarpirat J, Chaiwanichsiri D, Boonhong J (2008) Incidence of vertebral fractures in Thai women and men: a prospective population-based study. Geriatr Gerontol Int 8:251–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0594.2008.00475.x

Skov T, Deddens J, Petersen MR, Endahl L (1998) Prevalence proportion ratios: estimation and hypothesis testing. Int J Epidemiol 27:91–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/27.1.91

Hammami M, Picaud J-C, Fusch C, Hockman EM, Rigo J, Koo WWK (2002) Phantoms for cross-calibration of dual energy X-ray absorptiometry measurements in infants. J Am Coll Nutr 21:328–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2002.10719230

Reid DM, Mackay I, Wilkinson S, Miller C, Schuette DG, Compston J, Cooper C, Duncan E, Galwey N, Keen R, Langdahl B, McLellan A, Pols H, Uitterlinden A, O’Riordan J, Wass JAH, Ralston SH, Bennett ST (2006) Cross-calibration of dual-energy X-ray densitometers for a large, multi-center genetic study of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 17:125–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-1936-y

Limpaphayom KK, Taechakraichana N, Jaisamrarn U, Bunyavejchevin S, Chaikittisilpa S, Poshyachinda M, Taechamahachai C, Havanond P, Onthuam Y, Lumbiganon P, Kamolratanakul P (2000) Bone mineral density of lumbar spine and proximal femur in normal Thai women. J Med Assoc Thail 83:725–731

Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC (1993) Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res 8:1137–1148. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650080915

Newcombe RG (1998) Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 17:857–872. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e

Pongchaiyakul C, Songpattanasilp T, Taechakraichana N (2008) Burden of osteoporosis in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thail 91:261–267

Gallacher SJ, Gallagher AP, McQuillian C, Mitchell PJ, Dixon T (2007) The prevalence of vertebral fracture amongst patients presenting with non-vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int 18:185–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-006-0211-1

Black DM, Arden NK, Palermo L, Pearson J, Cummings SR (1999) Prevalent vertebral deformities predict hip fractures and new vertebral deformities but not wrist fractures. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res 14:821–828. https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.5.821

Clark P, Cons-Molina F, Deleze M, Ragi S, Haddock L, Zanchetta JR, Jaller JJ, Palermo L, Talavera JO, Messina DO, Morales-Torres J, Salmeron J, Navarrete A, Suarez E, Pérez CM, Cummings SR (2009) The prevalence of radiographic vertebral fractures in Latin American countries: the Latin American Vertebral Osteoporosis Study (LAVOS). Osteoporos Int 20:275–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-008-0657-4

Black DM, Cummings SR, Stone K, Hudes E, Palermo L, Steiger P (1991) A new approach to defining normal vertebral dimensions. J Bone Miner Res 6:883–892. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.5650060814

Ferrar L, Jiang G, Adams J, Eastell R (2005) Identification of vertebral fractures: an update. Osteoporos Int 16:717–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-005-1880-x

Grados F, Roux C, de Vernejoul MC, Utard G, Sebert JL, Fardellone P (2001) Comparison of four morphometric definitions and a semiquantitative consensus reading for assessing prevalent vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int 12:716–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980170046

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for their participation and the hospitals and their respective staff members for their assistance and Mr. Bryan Roderick Hamman and Mrs. Janice Loewen-Hamman for their assistance with the English-language presentation of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Thai Osteoporosis Foundation (TOPF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pongchaiyakul, C., Charoensri, S., Leerapun, T. et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic radiographic vertebral fracture in postmenopausal Thai women. Arch Osteoporos 15, 78 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-00762-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-020-00762-z