Abstract

This paper examines the influence of four variables on online tourism customer satisfaction: website image perceptions, online routine, online knowledge, and customer innovativeness, and their simultaneous effects. The analysis gauges the moderating role of three socio-demographic characteristics: gender, age group, and educational background. A sample of 3188 regular online consumers of the Portuguese leader in the tourism sector was analyzed using structural equation modeling. Results show that website image, routine, and knowledge significantly influence e-customer satisfaction. Only gender moderates the impact of website knowledge on e-satisfaction. These results entail a better understanding of customer specificities, with practical actions for addressing their real needs and expectations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The online world is full of possibilities, and from a commercial standpoint both customers and companies are becoming more and more aware of this new promising and challenging world.

For customers, Internet advantages consist mostly of a new way of searching for and comparing information on products and services, as well as a new, easy, and time-saving way of buying them. For example, 92 % of consumers now read online reviews (vs 88 % in 2014) and 40 % of them form an opinion by reading 1–3 reviews (vs 29 % in 2014) (Deloitte 2016). Finally, the same source concludes that 68 % of consumers say that positive reviews make them trust a local business more. Social networks are important today, but will be even more so tomorrow. 90 % of young adults (aged 18–29) use social media (compared to just 35 % of those over age 65). Fully a third of millennials say that social media is one of their preferred channels for communicating with businesses (Business2Community 2016).

More than 1 billion people worldwide use a tablet and/or a smartphone in 2015, representing nearly 15 % of the global population and more than double 3 years ago (eMarketeer 2015)

For companies, e-commerce allows them to cut down on structural costs, have a wider customer reach, and conduct easier transactions, among other commercial advantages, such as flexibility, enhanced market outreach, broader product lines, greater convenience, and customization (Srinivasan et al. 2002).

However, the online world also encompasses some disadvantages when compared to the offline world, such as the lack of social presence, which leads individuals to feel apprehensive with regard to online shopping, and puts companies in a constant frenzy to understand what can be done to overcome these drawbacks. Understanding what makes an individual shop or not shop online, and also choose one online shop over another, is one of the main wishes of companies with an online presence. However, such goals are not always easy to attain, since consumer behavior, and most specifically online consumer behavior, is not stable or linear, as they are affected by a wide variety of variables. In this context, appealing sites (with incorporated maps, webcams, and video content) can and will have an important role in meeting the customers in situ, instead of waiting for customers to look for the information, as in traditional paradigms where conventional offline business models expected customers to search/buy the products they need.

More demanding customers in today’s market means that this type of model is no longer sufficient. Hsieh and Chen (2009) study the service interface of tourism websites, and determine the priority of customer satisfaction factors. Research findings indicate that travel websites should acknowledge the factors that influence different customer groups. Since flexible business processing has the highest influence on customer satisfaction, these authors recommend travel websites to make their business processes simpler, in order to rapidly and effectively raise customer satisfaction.

The primary motivation for tourism providers to ensure customer satisfaction is the assumption that such efforts will lead to a higher level of repurchase intention, repeat attendance behavior, and customer loyalty (Yoon and Uysal 2005; Oliver and Burke 1999). High levels of customer satisfaction have been linked to customer retention, market share, loyalty, and consequently higher company profits (Tarasi et al. 2013).

Customer satisfaction has become one of the main objectives in all areas of business, especially in tourism, due to the higher level of expectations regarding the experience, more so than in other industries, such as banking or other financial sectors, where customers are looking for more functional advantages (Aminu 2012).

One of the most difficult problems is learning how to obtain this satisfaction, which involves identifying customers’ needs and desires, and transferring them to the product or service specifications offered.

Tourism is currently one of the most important sectors in major world economies.

Despite the crisis, 2015 marks the 6th consecutive year of above-average growth, with international arrivals increasing by 4 % or more every year since 2010 (UNWTO 2016a).

International tourist arrivals grew by 4.4 % in 2015 to reach a total of 1184 million in 2015, according to the latest UNWTO World Tourism Barometer (2016b). Some 50 million more tourists (overnight visitors) traveled to international destinations around the world last year as compared to 2014, according to the same source.

The importance of understanding what drives customer satisfaction within the Internet ecosystem has been a crucial concern, both in academia and in the business world. In particular, tourism—and the purchase of tourist products—creates the need for thorough research on this topic. This study takes a more in-depth look at its framework and analysis in order to find answers to a critical research question: What are the online factors influencing e-customer satisfaction within the context of purchasing tourism services on the Internet and in which way do socio-demographic characteristics moderate these relationships?

Despite previous studies, there is still a clear gap in the literature regarding the identification and assessment of antecedents influencing e-customer satisfaction in tourism. Hence, the current paper addresses the study of a set of four online determinants (website image perceptions, online routine, website knowledge, and innovativeness) and their impact on e-satisfaction, moderated by socio-demographic characteristics: gender, age group, and education.

Additionally, not only does e-commerce have its own determinants and defining elements, but also these elements change regarding the specific product category we are considering. Tourism, in this case, is directly associated with individual taste, preferences, and lifestyle and, therefore, represents a bigger challenge for online vendors, when satisfying their customer needs.

A questionnaire was applied to loyal customers of the Portuguese national leader in the studied sector, and a sample of 3188 individuals was analyzed. The research hypotheses and the validation of the proposed model were tested using Structural Equation Modeling.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Sect. 2 summarizes the most important findings of the theoretical background conducted, including the effects of four factors—perceived image of the site, routine, knowledge, and innovativeness—on satisfaction, and also the impact of the three socio-demographic characteristics as possible moderators in the model. The proposed conceptual model and the research hypotheses are also presented here. Section 3 presents the research method used: the sample and the research design, as well as the development of the measures used. Section 4 contains the main results of the statistical modeling, discussed from a point of view of theoretical and managerial contributions for the Discussion (Sect. 5). Prospects for future research are given in Sect. 6.

The research offers theoretical contributions and expands the understanding of consumer satisfaction and its antecedents. Moreover, practical insights are given to the online tourism providers.

2 Theoretical background

Customer expectations have rapidly changed, powered by new technology and the growing availability of cutting-edge features and services (Sheth et al. 2012). This has enabled companies to quickly respond to competitors’ innovations, lowering the impact that product differentiation has on markets. Thus, products have become considerably homogeneous and competition has increased. Only collaborative relationships with customers proved to be a wise way to distinguish organizations from their competitors, at a superior level: the augmented product level (Taleghani et al. 2011).

The perceptions that induce consumers in this buying process are not linear, which is why it is so important to understand and characterize consumers’ online behavior.

For example, Hernandez et al. (2010) found that the perceptions that induce individuals to shop online for the first time are not the same as those that create repurchasing behavior. According to these authors, customer behavior does not remain the same, because past experience creates an evolving perception.

The rapid growth of e-commerce reflects the compelling advantages that it offers over traditional commerce, to both retailers and customers.

Despite the innovations and changes brought about by the possibility of online transactions, it is important to bear in mind that e-commerce is not a replacement for traditional commerce channels, but complements them, allowing consumers to use multichannel retailing—view catalogs, visit stores, and browse Internet sites.

From a utilitarian point of view, and besides their intention to search for related information on the product, during their online buying process consumers are mainly worried about acquiring the products in an efficient, time-saving way, in order to reach their objectives with minimum effort (Childers et al. 2001). However, the perceptions that induce consumers to use this buying process are not linear, and that is why it is so important to understand and characterize consumers’ online behavior.

The way online information is organized and available to the consumer will determine their attitude towards the website, and the probability of shopping online on that same website in the future. The ease of use is one of the most important dimensions for customer satisfaction, particularly to new users (Gefen et al. 2003). Besides this dimension, a company’s website should be appealing—an attractive, easy-to-use interface is a quality factor considered by the customer (Van Riel et al. 2004). There is empirical evidence showing that a website and its functionalities add value to a company because they are highly interactive and can be customized. The site should be able to attract new customers, convince them to visit it, and, if possible, make a purchase (Huizingh 2002). e-customer satisfaction with a website can be improved by linking it to new technology developments that are taking place in the tourism and hospitality industry. More specifically, within the context of online tourism products and online purchase experience, huge information is generated electronically that can be stored in data warehouses and further explored by using big data analytics software, which will allow tourism services to be tailored and will even extend their reach by incorporating digitized self-servicing accessed via, for example, mobile devices. To illustrate this point, nowadays Starwood and Hilton hotel chains have guests’ check in via mobile phone (Rauch 2014). Indeed, the tourist experience is being transformed by mobile technology. Both smartphones and tablets have changed the way tourists process information and conduct transactions (Diener 2015). Furthermore, Motorola has developed a comprehensive mobile hospitality solutions’ portfolio, with the aim of transforming the guest experience from check-in to check-out with mobility. The range of applications includes mobile check-in, mobile concierge, mobile restaurant and food services, mobile ticketing, or mobile loyalty programs, among others (Motorola 2011).

The above studies point critical success factors regarding an effective strategic management of the digital approach, namely image and direction of the company, content and design, service quality, communication, maintenance, and monitoring. Each of these categories includes a number of relevant items that, if taken into account, ensure the company’s success in this virtual context.

There are clear gaps in the knowledge on the antecedents of satisfaction, although this construct is currently seen as a critical determinant of long-term financial performance in competitive markets (Lai et al. 2009). The primary purpose of the current paper is to examine an integrated model of satisfaction. Secondly, existing research mostly focuses on goods-producing firms and on retail stores (e.g., Bloemer and Ruyter 1997) and there are scant reports on customer satisfaction and service firms. Indeed, the few existing studies refer to the relationships between customers and brands in the US. Nevertheless, limited evidence suggests that consumers do not become satisfied the same way in different cultures (Lai et al. 2009). Thus, consumers’ reactions to service providers and loyalty formation may be unique and it is important to test it in different cultures. Moreover, the core constructs of the model being studied are likely to be universal and the relationships among them can be reasonably consistent across cultural and structural contexts.

The model structure is highly dependent on the nature of the study and time period. The choice of the constructs in the proposed model is also a consequence of two model structure types: a satisfaction model and an indirect model (Cronin et al. 2000). The model proposed in this paper examines the joint impact of a set of four online determinants (website image perceptions, online routine, website knowledge, and innovativeness) on e-satisfaction, moderated by socio-demographic characteristics—gender, age group, and education.

2.1 Website image perceptions

The website image is an important dimension of the online relationship, and represents a key element with the ability to influence customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, and brand image (James et al. 1976, Sanchez-Franco and Rondan-Cataluña 2010). In the context of electronic marketing, where the exchange process takes place in a virtual space characterized by greater uncertainty and risk, and where opportunistic behavior provides more room for maneuver than in the physical market environment, the image becomes even more important for the success of the relationship (Mostafa et al. 2006; Oh et al. 2008).

In the online shopping context, consumers measure their Internet shopping experiences in terms of perception and evaluation of online service quality. According to Kim and Lennon (2006), retailers must take into consideration certain dimensions of the online service that affect customers’ perceptions of service quality, which, among other things, has to provide information. This dimension is considered critical for online apparel retailers, since customers cannot feel or examine the product, and therefore need an adequate amount of information to make a purchase decision. The graphic style, like zoom functions and video content, is also crucial (Kim et al. 2009).

A website must be easy to use and engaging. Given the millions of sites available, online vendors must try to understand ways to attract users, retain them, and keep them coming back for more. According to Pandir and Knight (2006), a key way of influencing repurchase intention is through the homepage design. In fact, previous studies have suggested that visual appearance is extremely important in users’ preferences (Shenkman and Jonsson 2000; Kim and Niehm 2009), and that consumers prefer beautiful websites, even perceiving them to be more usable. A website’s image is transmitted through the Internet shopping environment, together with its hedonic aspects, such as web atmospherics. Although web-based stores also use music/sound to attract consumers, visual factors such as screen layout information display, color, pictures or images, banner ads, size of characters and signage, and video content are more obvious in establishing store atmosphere in web-based environments.

According to Oh et al. (2008), images also contribute to create a feeling of convenience, as well as to a perception of higher quality merchandise. With regard to online storefront designs, the name attributed by Oh et al. (2008) to the website’s homepage, it was found that a thematic storefront with a design that reflects a store’s identity and presents products in a lifestyle-type environment will be more appealing and entertaining to costumers, communicating a safer environment. Other elements like close-up pictures and zoom functions, 3D virtual product presentation, and video content improve consumer’s perceptions, enjoyment, and involvement (Kim et al. 2009; Koo and Ju 2010).

Furthermore, the presentation of products—website layout and design—significantly increases customer satisfaction. Danaher et al. (2006) use a set of features (such as graphics, text, and advertising content) included in websites to try to explain the duration of the visit to a store. There seems to exist a strong correlation between image and environment that fuels the customer’s willingness to repeat purchases on the Internet, contributing positively to the overall impression and satisfaction generated by the organization (Bloomer et al. 1998).

Website image perception is thus likely to have an impact on e-customer satisfaction for online purchases. We therefore propose that:

H1

Website image perceptions influence positively e-customer satisfaction when purchasing tourism products or services online.

2.2 Online routine

Motives underlying satisfied customer behavior can help distinguish between spurious satisfaction, which can be described as inertia, and true satisfaction, which potentially signifies a commitment to the brand or company. Inertia may be rather durable since it is formed based on habits or routines that enable consumers to effectively cope with time pressures and search efforts (Pitta et al. 2006).

Ambler (1997: p 285) states that the historical behavior of customers in terms of purchasing options gives “the best estimate for their future behavior.” Campbell (1997) defines inertia as a condition where repeat purchases occur on the basis of situational cues rather than on strong partner commitment.

According to an expansion of the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen 2001; Bentler and Speckart 1979), a person’s former behavior can explain their current behavior. In a similar fashion, a considerable proportion of customers bookmarks their favorite electronic commerce websites, and is more likely to visit them than other sites. These customers visit the sites out of habit rather than by conscious determination on the basis of perceived benefits and costs offered by e-businesses.

As in the case of traditional procurement, Foster and Cadogan (2000) argue that online shopping behavior becomes routine after a certain time. The author considers routine as the condition where a repeat purchase occurs based on situational reasons, which become comfortable and increase customer satisfaction and customer loyalty, rather than due to a high commitment between the parties. For reasons related to habit, 40–60 % of consumers continue to buy at the same store (Beatty and Smith 1987), so when a client becomes accustomed to buying on a particular site, their decision process becomes routine (Gefen et al. 2003).

Corstjens and Lal (2000) explain that this phenomenon is due to a psychological commitment to prior choices and to a customers’ desire to minimize their cost of thinking. This so-called inertia effect is rational because it helps consumers achieve satisfactory outcomes by simplifying the decision-making process, while saving decision-making costs (Vogel et al. 2008; Wong 2011). This takes place automatically and without a conscious thought.

Many studies give empirical evidence for habitual behavior (Anderson and Srinivasan 2003; Beatty and Smith 1987; Rust et al. 2010).

There is a feeling of high insecurity in the context of e-commerce due to the new technologies and complex security problems, which arise frequently in the media, and to the lack of experience in this new process of search and purchase. In this environment, routine plays an even more important role, since there is a spatial and temporal separation between buyers and players. In short, there is ample evidence to suggest that inertia plays a pivotal role in consumer choice and satisfaction.

Online routine is likely to take place due to inertia, since consumers are prone to behave based on habit, convenience, and time saving.

To summarize, there is large evidence suggesting that inertia plays a very important role in consumer choice and satisfaction (Polites and Karahanna 2012), and the arguments presented lead to the formulation of the second research hypothesis:

H2

Online routine has a positive effect on e-customer satisfaction when purchasing tourism products or services online.

2.3 Website knowledge

Bettman and Park (1980) understand product knowledge as the amount of information stored by the specific individual regarding their possible buying alternatives, as well as the perception the individual has about their own level of knowledge.

Content availability and depth is often mentioned as one of the most important reasons for online shopping (Hoffman and Novak 2009), as well as the quality of information that, coupled with the ability and ease of search for products and prices, increase satisfaction, the intention to visit the website again, and the willingness to repurchase (Zeithaml et al. 2002).

Developing the online shopping experience has been a concern for online vendors, and several studies have been conducted in order to find how social presence can be induced on online sites (Hassanein and Head 2007; Cyr et al. 2007). Besides sociability, other dimensions contribute to the consumers’ online shopping experience and knowledge of the site. According to Childers et al. (2001), both utilitarian benefits (efficiency, speed, lack of irritation) and hedonic benefits (fun, playfulness, and entertainment) positively influence the online buying experience and website patronage. Additionally, if e-retailers maintain shopping situations where transactions are secure, private, and ensured, e-shoppers are more likely to be inspired to repurchase from the same vendors (Lu et al. 2013).

According to Kotha and Venkatachalam (2004), investing to provide an online buying experience represents a viable long-term competitive advantage, since the shopping experience influences consumer responses such as satisfaction and purchasing behavior (Fiore et al. 2005).

The image of the site includes different aspects of the physical environment. Indeed, the market space will be characterized by greater frequency and regularity in interaction and communication activities, and in greater information sharing, resulting in a major feature of the virtual environment—the “convenience”—which can be defined as the set of customer perceptions regarding the time and effort spent in the utilization or exchange process. Apart from ease of access and availability of information content, convenience includes the time spent using the service, availability of credit or payment automation, the variety and breadth of the assortment of products and services, and service delivery (Berry et al. 2002).

There are several reasons to expect that knowledge and experience with the site may contribute to customer satisfaction with online tourism products (Casalo et al. 2008). On the one hand, it increases the level of familiarity and comfort of the potential buyer, which encourages positive feelings. Moreover, empirical studies show that consumers will more readily access sites they already know and are familiar with rather than undertake a new search process each time they want to make an online purchase (Urban et al. 2009), preferring the prospect of a one-stop shop (Narayandas et al. 2002). On the other hand, consumers cannot be faithful to a site unless they have information that goes well beyond what one learns from a simple display.

Knowledge of the site contributes to customer satisfaction, especially in online tourism products, due to the increased level of familiarity and comfort of the potential buyer with the site (Urban et al. 2009).

Website knowledge involves experience and consumer familiarity with the site. Therefore, the following research hypothesis is established:

H3

Website knowledge has a positive effect on e-customer satisfaction when purchasing tourism products or services online.

2.4 Customer Innovativeness

The establishment of a long-term relationship varies with the degree of desire for innovation manifested by customers (Midgley and Dowling 1978) which, in cases of a strong innovation focus, will generate an attempt to acquire something “unique.” Steenkamp et al. (1999, p 56) define consumers’ desire for innovation as “a predisposition to buy new and different products/brands over previous choices and traditional standards.”

Innovativeness is the degree to which an individual is receptive to new ideas. It is regarded as a personality trait.

Domain-specific innovativeness (DSI) measures how innovative a consumer is in a specific product field. DSI was developed in several studies because innovative behavior was not apparently consistent across domains. Since online shopping can be viewed as an innovative way of shopping, innovativeness should have a bearing on its adoption. Several studies concluded that DSI had a significant positive correlation with online shopping intention and use.

However, results for general innovativeness were mixed. While Limayem et al. (2000) and Donthu and Garcia (1999) found a positive correlation between general innovativeness and purchase intention, Sin and Tse (2002) found the correlation to be non-significant.

Vandecasteele and Geuens (2010) incorporate different motivations into a multi-dimensional innovativeness scale to better account for the consumer–product relationship. Four types of motivation underlie consumer innovativeness: functional, hedonic, social, and cognitive.

Understanding the effect of innovativeness on adopting an online shopping behavior is important for targeting the right customers. In this study, the search for innovativeness is understood as the virtual affinity customers have for new products and services (Burns and Krampf 1992), which means that an online customer with a desire for innovative products tends to be more unsatisfied with and less loyal to one site. Other authors have concluded that innovative customers are more involved and have greater knowledge about online products and services, compared with non-innovative ones. As a result, the former tend to evaluate more alternatives.

Customer innovativeness is seen as a predisposition for change. In the current research, it might involve receptiveness to consider other websites within the consumer decision-making process. Consequently, the following research hypothesis is formulated:

H4

Consumer desire for innovativeness has a negative effect on e-customer satisfaction when purchasing tourism products or services online.

2.5 e-Customer satisfaction

Customer satisfaction is an affective response to a certain purchase, and determining its causes and consequences is an important goal in consumer marketing (Chang and Chen 2009). However, a number of researchers have focused on the experimental aspect along with other important elements to better estimate customer satisfaction (Cole and Chancellor 2009; Jin et al. 2015). Satisfaction represents an essential ingredient for a successful business relationship, not only in the context of traditional commerce, but also within business-to-consumer electronic commerce (Kim et al. 2009). Online information search and satisfaction with the website ultimately chosen for contracting services are largely individual experiences (Sabiote et al. 2013) and, according to Anderson and Srinivasan (2003), a dissatisfied customer is more likely to search for alternative information and change to a competitor than a satisfied customer. Also, according to these authors a dissatisfied customer is more likely to resist the efforts of the current retailer to develop a closer relationship, and is more likely to take steps to reduce their dependence on that retailer.

e-Customer satisfaction in this study does not focus on the end satisfaction with the tourism service, but rather on the customer experience with the website that leads to the online purchase of that service.

2.6 Moderating role of the socio-demographic characteristics: gender, age group, and education

There is a stream of research that consistently finds variations in satisfaction ratings based on numerous customer characteristics (e.g., Venn and Fone 2005). In the last decade, where there was an exponential growth in the importance of relationships and in the usage of the digital context to strengthen them, research suggests that customer characteristics moderate the relationship between behavioral outcomes and satisfaction (Baumann et al. 2005; Homburg and Menon 2003; Kim et al. 2007; Chau and Ngai 2010; Lo et al. 2011).

Gender, age, and education have been used in research in order to assess the extent to which these demographic variables have a real impact on tourism behavior, and also within the online tourism perspective.

These three characteristics have been reported to influence customer satisfaction ratings (Tucker and Adams 2001; Gilbert and Veloutsou 2006). Gilbert and Veloutsou (2006) studied customer satisfaction across six industries. Significant differences in demographic characteristics among the respondents in all industries were found to exist by gender, age, and education.

Tellis et al. (2009) argue that there is, a priori, no general hypothesis concerning gender in consumer innovativeness studies, and this remains an underexplored research area. Kim et al. (2011) examine how two consumer innovativeness measures (domain-specific innovativeness and general innovativeness) in a highly globalized product are related to gender. These authors found the two consumer innovativeness measures to be significantly influenced by gender. Furthermore, consumers’ decision processes were found to have idiosyncratic patterns with regard to consumer innovativeness and the gender moderator.

As far as tourism is concerned, gender has been used as one of the most common forms for segmentation, as well as for understanding the behavior of online consumers. Kim et al. (2007) examined gender differences taking place within the functionality of online travel websites, content preferences, and search behavior. Research findings support the argument that gender exerts a substantial influence on attitudes towards information channels, preferences, and satisfaction concerning travel website functionalities. Gender was found to influence both cognitive and affective assessment of the perceived image formation of a tourist destination (Beerli and Martin 2004). Moreover, Lepp and Gibson (2003) find that women perceive a greater degree of risk than men in terms of health and food in international tourism.

Garbarino and Strahilevitz (2004) examine how gender influences perception of risks associated with shopping online and the effect of receiving a site recommendation from a friend. The results suggest that not only women perceive higher levels of risk in online purchasing than men, but also having a site recommended by a friend leads to a greater reduction in perceived risk and a stronger increase in the willingness to purchases products and services online among women than men and, accordingly, it creates greater satisfaction.

In a study of young tourists’ perception of danger within the urban holiday environment of London (UK), Carr (2001) concludes that men and women should not be regarded as homogeneous cohorts. Differences in perceived image across gender classes are also confirmed by Govers (2005). Furthermore, Yoo and Gretzel (2008) report the differences between males and females with regard to what motivates consumers to write online travel reviews.

Chau and Ngai (2010) look at perceptions, attitudes, and behavior of the youth market for internet banking services. The authors found that young people (aged 16–29) have more positive attitudes and behavioral intention towards using these services than other user groups. For many authors, age moderates several relationships with satisfaction (Baumann et al. 2005; Homburg and Giering 2001). Mittal and Kamakura (2001) find that the relationship between satisfaction scores and repurchase behavior is stronger for younger than for older consumers. East et al. (2000) propose that older consumers have more free time, are able to spend more time shopping, and thus are able to shop at multiple stores. Some studies have found that the middle age segment is the most satisfied and loyal.

Im et al. (2003) explore the relationship between natural consumer innovativeness, personal characteristics, and new product adoption behavior. They found that the personal characteristic of age is a stronger predictor for new product ownership in the consumer electronics category than innate consumer innovativeness as a generalized personality trait.

Kumar and Lim (2008), when studying the effects of age on mobile service quality perceptions and evaluating its impact on perceived value and satisfaction, find different mobile service quality attributes as important to age groups as well as significant differences in terms of the effect of perceived economic and emotional value on satisfaction.

When studying the influence of online travel reviews, Gretzel and Yoo (2008) claim that age groups were associated with different perceptions and use behaviors. Age has also been reported in the tourism literature as driving differences in the use of information sources, namely regarding the higher importance given to word of mouth by older tourists (Patterson 2007).

Lastly, the level of education was found to influence cognitive and affective assessment of tourist destination perceived image formation (Beerli and Martin 2004). Lo et al. (2011) describe a strong relationship between education and the likelihood of using electronic media to share pictures, with well-educated people being far more likely to embrace this technology than less-educated individuals. The differences in use levels become more pronounced when participation rates by education cohorts are compared.

Heung (2003) reported that travelers with higher education levels are more likely to use the Internet for online purchase of travel products. Moreover, with the aim of developing profiles of users of travel websites for planning and online experience sharing, Ip and Law (2010) found that education level positively influences tourists’ willingness to share travel experiences.

People with higher education levels are believed to engage in greater information gathering and usage before decision making (Capon and Burke 1980). As a result, more highly educated consumers have greater awareness of alternatives. However, Keaveney and Parthasarathy (2001) found that online service continuers have higher average education levels than switchers.

To summarize, Van den Poel and Buckinx (2005) also suggest that gender is an important demographic variable related to online purchasing behavior: men have a higher tendency to purchase during their next website visit when compared to women. Consumers in older age groups (aged 40 and older) considered community to be the most important fashion website attribute. Consumers with lower education (high school) considered content (website design, multimedia content, inviting homepage) more important than consumers with a graduate level of education.

Considering the above, hypotheses 5, 6, and 7 are defined as follows:

H5

Gender moderates the relationship between online purchase determinants and e-customer satisfaction.

H6

Age moderates the relationship between online purchase determinants and e-customer satisfaction.

H7

Education moderates the relationship between online purchase determinants and e-customer satisfaction.

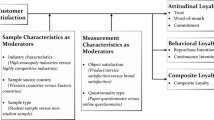

Based on the above, we propose a model to explain customer satisfaction in the context of online tourism products and online purchase experience. Four main determinants were considered: website image perception, online routine, website knowledge, and innovativeness. The path diagram of the proposed model is presented in Fig. 1.

3 Methods

3.1 Sample and research design

A partnership was established with the Portuguese market leader in the online tourism sector in order to use its customer database, which includes 140,000 registered clients. Portugal is an interesting field for this study in light of the fact that the degree of penetration of Internet users in the total population equals, in 2015, 67.6 %, clearly above the world average of 46.4 % and in a short distance to European average of 79.3 % (Internet World Stats 2016).

Taking into account the visible growth that e-commerce is undergoing in recent years around the world, a Portuguese company can be seen as a window to the future of these digital relationships. With this growth of Internet users, another trend that is growing is related with social networks. One example of this is Facebook that had in Portugal 5,600,000 Facebook subscribers in the end of 2015 (Internet World Stats 2016).

This is an online operator, in a very competitive market, offering several different kinds of tourism products (e.g., flights, experiences, hotels) all over the world, either separately or in bundles. The 40,000 clients that can be considered regular online consumers (customers that make purchases at least twice per year) compose the target population of this study. The company placed a banner with a direct link to a web-based questionnaire, both in its website home page and in the newsletter. Additionally, the company also sent an institutional e-mail to the 40, 000 regular buyers, reinforcing the importance of the study and offering a discount voucher of 10 Euros to be used in a future purchase. A sample of 3188 voluntary respondents was obtained within the time limit of 1 month allowed for the data collection.

In terms of the respondents’ profile, 51.4 % of them were female, 44.5 % of the respondents were between 25 and 34 years old, 50 % of the respondents have higher education qualifications and live in urban areas, 51.1 % of the respondents use the Internet preferably at home, and 46 % use it in the workplace. In terms of income, 38 % of the respondents have a monthly family income of more than 2500 Euros, and only around 4 % of the respondents belong to a family with an income lower than 750 Euros.

94 % of the respondents consider recreational opportunities as the main reason to visit the company’s website. However, despite making purchases on this site, 79.8 % of the respondents usually visit other sites related to tourism, national or international, which may be stated as a kind of “polygamous” loyalty. Regarding the use of the Internet, 99 % of the respondents do it for purposes other than just buying tourism products: 27 % see the Internet merely as an information search engine, while 22 % use it to search for information and to acquire services. 35 % also use it to purchase products online other than tourism ones. 30 % of the respondents have been clients of the company for at least 1 year, and 60 % of them for more than 1 year but less than two.

Regarding the initiative to visit tourism websites, 64 % of the respondents made a personal decision to visit sites related to tourism, whereas 22.6 % followed the recommendation of friends, colleagues, or family. The mass media have a crucial importance for 3.5 % of the respondents. There is a strong link between those who purchase airline tickets and those that use the site to make hotel reservations, purchase holiday packages, or simply look for a “getaway.”

A preliminary version of the questionnaire was subjected to a pre-test in order to identify potential gaps in the construction of the instrument and problems in understanding the questions, thereby attempting to ensure the adequacy of the questionnaire to the problem. Minor changes were then made to the preliminary version of the instrument. Besides socio-demographic information, the final version of the questionnaire asked for information on customer satisfaction regarding their experiences of purchasing online tourism products, as well as information on customers’ opinions concerning website image, online routine, website knowledge, and innovativeness.

3.2 Measure development

Based on the literature review conducted regarding e-customer satisfaction and its possible determinants, measurement scales were developed for the five latent constructs in the proposed model: website image perception, online routine, website knowledge, innovativeness, and e-customer satisfaction. Following the recommendation of Churchill (1979), several items were used to measure each construct. The items used were mostly adapted from published scientific papers. However, some minor changes had to be made to accommodate the online context of the current research.

The construct website image perceptions was measured using four items adapted from Likert scales proposed by Parasuraman et al. (1991), Dodds et al. (1991), Doney and Cannon (1997), and Ribbink et al. (2004). The construct online routine was measured using three items, adapted from Gremler (1995). Website knowledge was measured using five items adapted from Smith and Park (1992). Innovativeness was measured by three items adapted from a scale by Steenkamp et al. (1999)—this one previously adapted from Baumgarten and Homburg (1996)—and another scale by Yi et al. (2006). Finally, e-customer satisfaction was adapted from scales proposed by Bloemer and Ruyter (Bloemer et al. 1998), Garbarino and Johnson (1999), Macintosh and Lockshin (1997), Reichheld (2001), Oliver (1981), and Caprano et al. (2003), where four items were considered.

Table 1 displays the complete wording of each scale item present in the final model, as well as some measurement properties of the scales used. All the items were measured against seven-point Likert-type scales, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. This type of scale has been increasingly used in studies regarding relationship marketing, in particular Morgan and Hunt (1994), Kumar et al. (2009), Siguaw, Simpson and Baker (Siguaw et al. 1998), and Foster and Cadogan (2000). The three items measuring innovativeness were reverse scored.

A Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the measurement model using LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog and Sörbom 1996). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was later adopted to test the research hypotheses and to validate the proposed model. Since the observed variables were measured on ordinal scales, polychoric correlations were computed, with listwise deletion of missing data. A Robust Maximum Likelihood (RML) estimation procedure, proposed by Satorra and Bentler (1990) and implemented in LISREL, was used to estimate all the models. This is considered in the literature as a consistent estimator that is asymptotically unbiased and efficient, scale invariant, and scale free (not affected by changes in measurement units of the manifest variables (see Hair et al. 2010). In this robust estimation procedure, model estimation is performed using maximum likelihood and estimated standard errors, while the t values and the χ 2 test statistic are subsequently adjusted.

In order to assess model-data fit, the following goodness-of-fit measures were used: Satorra–Bentler scaled corrected Chi square (χ 2) and corresponding degrees of freedom (df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root-Mean-Square Residual (SRMR)

Composite reliability was assessed following Bagozzi and Yi (1988). In line with the recommendations in Fornell and Larcker (1981), the average variance extracted (AVE) was computed for each construct and discriminant validity was assessed by comparing AVE values with the squared correlation between each pair of constructs.

4 Results

4.1 Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA was used to construct a measurement model for the five latent variables, measured by 19 indicators. Table 1 displays the complete wording of the items that were used. The CFA model showed an adequate model-data fit: χ 2 = 468.91, df = 142, CFI = 0.99, IFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.031, and SRMR = 0.053. The estimated (standardized) factor loadings that were obtained are displayed in Table 1, with the corresponding t values.

The convergent validity of the indicators is corroborated since all obtained t values are high (the smallest t value equals 16.9). All standardized factor loadings are above 0.6 and the R 2 values range from 0.40 to 0.81.

It is possible to conclude that the indicators measuring each construct have internal consistency, since the obtained Composite Reliability (CR) values range from 0.81 to 0.93, all above the minimum value of 0.70 recommended in the literature (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Obtained Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values are all above the minimum recommended value of 0.5, and range from 0.58 to 0.77, implying that for each construct in the model the amount of variance captured by the construct is higher than the variability due to measurement error. In short, there is statistical evidence that the scale items used provide a good representation of the constructs in the model.

The estimated correlations between the five latent dimensions are presented in Table 2, and range, in absolute value, from 0.30 (a negative correlation between innovativeness and website image perceptions) to 0.82 (between website image perceptions and website satisfaction).

4.2 Structural equation modeling

In a second stage, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the research hypotheses and to validate the proposed model. Each research hypothesis postulates a relationship between one of the independent variables (website image, online routine, website knowledge, and innovativeness) and the dependent variable (satisfaction). The path diagram of the global SEM tested with the estimates obtained in a completely standardized solution is displayed in Fig. 2.

It is possible to conclude that website image perceptions, online routine, and website knowledge have significant impacts on e-customer satisfaction, with standardized regression coefficients of 0.50, 0.34, and 0,13, respectively (and t values of 8.4, 10.6, and 2.6, respectively). However, the impact of innovativeness is non-significant: regression coefficient of 0.01; t value of 0.13.

The obtained goodness-of-fit measures indicate that the proposed SEM has an acceptable model-data fit: Satorra–Bentler scaled corrected Chi square = 468.91; df = 142; RMR = 0.053; NFI = 0.99; CFI = 0.99. Results also confirm the nomological validity of the global model, with a ratio χ 2/df = 3,3 and RMSEA = 0.031.

4.3 Moderating effect of gender, age group, and education

Hypotheses 5, 6, and 7 postulate that gender, age group, and education moderate the relationship between online purchase determinants and e-customer satisfaction. In order to test these moderating effects, the sample under analysis was divided into two groups for each of the moderator variables: males (48.6 %)/females (51.4 %); younger (52.5 %)/older (47.5 %); lower education level (23 %)/higher education level (77 %). A multiple group analysis was then conducted separately for each of the three socio-demographic characteristics in order to examine and test the moderating effects. SEM with free parameter estimates was first tested for each group. Secondly, SEM was considered with an equality constraint (between the two groups for each socio-demographic characteristic) between each online purchase determinant and e-customer satisfaction. The difference in the χ 2 test statistic (with Δdf = 1 in each model) was used to test parameter invariance. Table 3 summarizes the main results obtained. Parameter estimates in a common metric completely standardized solution are presented to allow comparison between the two groups.

Gender has no significant moderating effect on the relationship between website image perceptions and e-customer satisfaction. However, gender is a significant moderator of the relationship between website knowledge (and online routine) and e-satisfaction. Males present higher effects in terms of website knowledge, whereas females have a more marked effect with regard to online routine.

The age group is a significant moderator of the relationship between online routine and e-customer satisfaction, with younger customers having a higher impact (0.35) than older customers (0.32). No significant moderating effect is obtained for the age group when the relationship between website image perceptions or website knowledge and e-customer satisfaction are considered.

Finally, education level does not have significant moderating effect.

5 Discussion

The objective of this research is to examine, through a conceptual model and related empirical data, the influence of the specific purchase determinants on e-customer satisfaction within the Internet context.

This study aims to answer a research question, presented in the beginning of this study: What are the online factors influencing e-customer satisfaction within the context of purchasing tourism services on the Internet and, in which way, do socio-demographic characteristics moderate these relationships? The results obtained in this study allow us to conclude that website image perceptions, online routine, and website knowledge are the most important factors influencing e-customer satisfaction in e-tourism purchases and that socio-demographic characteristics, such as gender and age group, partially moderate the relationships among the previous three factors and online satisfaction. We go on to provide a more in-depth discussion of the results below.

The sample under analysis includes regular customers of this company, of whom about 80 % usually search other sites related to sales of online travel products, which can be understood as polygamous loyalty (Uncles, Ehrenberg and Hammond Uncles et al. 1995). In increasingly competitive markets, it is not easy to find regular online buyers for just one brand. Internet users tend to use different sites for different purposes and needs. This behavior has to do with the fact that there is a low cost associated with changing the point of purchase on the Internet and, in general, there are no monetary losses associated with these transfers.

The proposed conceptual model establishes a relation between four specific online determinants—website image perceptions, online routine, website knowledge, and innovativeness—and e-customer satisfaction. Additionally, the moderating role of socio-demographic characteristics—gender, age group, and education—on the relationship between the online determinants and e-customer satisfaction was investigated.

Results from the SEM analysis confirm the first three research hypotheses and suggest that H4 should be rejected. H1 postulated a positive impact of website image perceptions on e-customer satisfaction. A standardized regression coefficient of 0.50 was obtained, suggesting that for the customers of the company website image perceptions have a strong impact on their satisfaction. This is in line with previous results in the literature. For example, for Koivumaki et al. (2002), online presentation of products had a high influence on customer satisfaction, and it cannot be forgotten that a retailer’s website is the primary point of contact for an online transaction; it is where customers can learn about an organization’s attention to detail and the importance given to customer satisfaction.

As postulated in H2, routine is a positive satisfaction determinant for the customers in the study. A standardized regression coefficient of 0.34 was obtained, which is much lower in magnitude than the first effect (between website image perceptions and e-customer satisfaction). This means that consumers will prefer to buy from the same retailer from previous purchase occasions, even though they might perceive other retailers as providing the same or better benefits (Vogel et al. 2008).

H3 postulated that website knowledge has a positive influence on e-customer satisfaction. In this study, this relationship proves to be significant, with a standardized regression coefficient of 0.13. In this sense, this result is in line with those of Zeithaml et al. (2002), who determine that website knowledge is highly significant in online shopping and a clear determinant for e-customer satisfaction. Website knowledge is rooted in the concept of convenience—the perception of the time and effort it takes to buy a product or service (Berry et al. 2002). It also reduces uncertainty, which makes it an important determinant for online customer satisfaction.

H4 postulates a negative influence of innovativeness on e-customer satisfaction. A non-significant estimate was obtained, thus indicating that there is no significant influence from innovativeness on e-customer satisfaction. The long-term relationship depends on the innovation level of each customer (Midgley and Dowling 1978), translated by the desire to try to get something “unique” (Burns and Krampf 1992). Steekamp et al. (1999) argue that an online customer with a desire for unique products and relationships tends to search more and be less resigned to and therefore less satisfied with a website, which was not confirmed in this study since a non-significant effect was obtained.

H5 postulates that gender has a moderating role between the online purchase determinants and e-customer satisfaction. This hypothesis was partially accepted since this study indicates that gender has significant moderating effects. These results several other studies, such as that of Gilbert and Veloutsou (2006).

H6 postulates a moderating effect of age between the online purchase determinants and e-customer satisfaction, as the stated hypothesis. A significant effect was found in the relationship between online routine and e-customer satisfaction, with a higher impact for younger customers, which is consistent with the study developed by Chau and Ngai (2010) already mentioned in the literature review.

H7 posits the moderating effect of the level of education on online purchase determinants and e-customer satisfaction. However, no significant moderating effect was observed, since no significant differences were found between individuals with lower and those with higher education levels, with regard to the impact of website image perception, online routine, and website knowledge on e-customer satisfaction. Our results are not in line with Chen and Lee (2005), who found differences in important perceptions regarding website image on price, brand, and quality, among others, in respondents with a university-level background versus a training college background. However, this result is in line with that of Cooil et al. (2006) where education is not a predictor in the best model and does not have significant incremental value as a moderator in the proposed model.

The findings provide both theoretical and managerial insights. Indeed, this research strengthens the idea that the relationship between companies and their customers should be treated, both by academics and managers, as a process of mutual value development and a new strategic marketing orientation. On the other hand, technology should not be seen as just another element to take into account in business development, but increasingly as a major factor in the strategic orientation of companies (Srinivasan et al. 2002), particularly towards its customers.

5.1 Theoretical implications

The basic aim of this study is the development and validation of a marketing model that helps increase scientific knowledge and at the same time has applicability in the world of business management. Although the study area and more specifically the scope are still relatively recent, the aim of this paper is to contribute to the development of a theoretical knowledge. In this sense, we attempt to systematize the concepts related to the relationship determinants, as well as their relation with the satisfaction construct in a process of relationship marketing within an online context. Also, this study intended to examine the impact of socio-demographic variables—age, gender, and education—in a global model where a relationship between the independent constructs (the online purchase determinants) and e-satisfaction is presented. Previous research mainly focuses on the impact of these variables on website image (Chen and Lee 2005), the capability to predict consumer purchases (Van den Poel and Buckinx 2005), and also innovativeness (Kim et al. 2011)

Another contribution of this study is the development of a deeper understanding of online consumer behavior and the purchase decision process in the digital context, bearing in mind the importance of e-customer satisfaction determinants on the purchase of online tourism products.

From the literature review conducted, it is possible to conclude that several studies in this area are based on empirical work conducted with students within laboratory conditions as is the case of Baker et al. (2002). The present study obtains the views of end customers, collecting information from individuals who are actual buyers of online tourism products from a real online company, a market leader in the sector being studied.

5.2 Managerial implications

Our research findings are likely to bring added value to tourism businesses.

A first practical contribution of this research for the online business tourism sector lies on the data pool, a large sample composed of clients of the national market leader, which can lead to a customer profile and corresponding purchasing behavior regarding online tourism products, potentially extendable to the sector.

The profile obtained is not only socio-demographic but also behavioral, which allows the evaluation of the primary determinants for the establishment and maintenance of long-term relationships with customers, crucial for business, and the consequent definition of strategic options, contributing to a management diagnosis of the sector. This research highlights the impact of customer relation activities, such as ensuring the quality of website image, intended to represent a contribution to the sector, alerting managers with the need to overcome this weakness.

It provides important insights for a better understanding of the customer profile for online tourism products, grouping purchase satisfaction determinants in this digital context with socio-demographic variables, in order to ensure a more precise customer segmentation approach, and the definition of specific actions based on the profile of each customer. For example, by having each customer registered in the website, the company is able to track his/her consultation (information search stage in the consumer decision-making process) and buying (purchase stage) behavior and, consequently, to propose specific and unique products/services/experiences adapted to each profile. This could be extended by allowing customers to register their testimonies on the website after experiencing the service (post-purchase stage), with the identification of the “cluster” they belong to. Hence, firms can personalize the website as well as provide customized service recommendations to different kind of tourists.

Market research from clickstream data can also be enhanced by stimulating users to sign in using their Facebook account, since that will allow the provider to collect further information about the consumer and thus fine tuning services to be offered to the tourist.

This segments’ diversity, evident in the conceptual model, allowed us to capture the behavioral complexity of the individuals, as well as the dynamics of the various influences. In addition, this study shows differences between socio-demographic characteristics, such as gender and age group, in terms of the impacts of both online routine and website knowledge on e-customer satisfaction, hence providing an opportunity to be exploited by tourism companies, by introducing specific actions in order to meet the different group specificities.

Another contribution of this study is to reinforce the idea that marketers should pay more attention to website image perceptions since it has been shown to influence customer satisfaction for online tourists. Managers should enhance website image perceptions by tourists through an easily accessed and technology-advanced website providing appealing information.

This is in line with Berry et al. (2002), who argue that it is important for organizations to make real efforts towards facilitating access to content and making it easily available, offering an easy search engine process, automation of payment (no need to resort to call centers), providing variety and innovation in tourism products offered, and guaranteeing a just-in-time delivery process. Also, from a technological standpoint, it is essential to ensure easy navigation with speed and ease of use, as concluded by Turban et al. (2002).

Routine purchases increase the satisfaction of the customer, and in the online context inexperience in the decision-making process (Gefen et al. 2003) makes navigation routine seem more comfortable. Thus, a fourth contribution of this study is the suggestion to organizations that operate in this context not to take this behavior for granted, because these individuals are at the same time curious and demanding in the relationship they have with the organization, and a quality loss may lead to the abandonment of many satisfied customers. Furthermore, to stimulate online routine in its users via convenience can be targeted with the aim of improving e-customer satisfaction.

The organization should harness these values in order to improve their site and offer better personalization for each customer as a way of guaranteeing satisfaction. Clearly, customers prefer to buy from the same retailer from previous purchase occasions, even though they might perceive other retailers as providing the same or better benefits (Vogel et al. 2008). Hence, a tourism website ought to give customers a comfortable and easy experience, making it easy to navigate throughout all the “visit” and promoting familiarity with its functionalities, thus increasing website knowledge by consumers and, in the end, customer satisfaction.

6 Limitations and indications for further research

Despite these interesting findings, this study has several limitations that also provide important future research issues.

A first limitation of this research is related to the sample used. Our sample includes volunteers, which are regular clients of just one company, even if that one is the national leader of the sector being studied. This raises issues concerning the representativeness of the target population and therefore conditions the generalization of the results to other sectors and even to other companies within the same sector.

Another limitation concerning the generalization of conclusions is related to the cultural context, in the sense that this study comprised only Portuguese customers, and consequently these respondents may clearly differ from customers from other cultures. Wang et al. (2012) also pointed this out as a limitation in their study using social websites in China, and compared the differences with western consumers. Thus, additional research should be conducted using our proposed conceptual model in other cultural contexts.

One possible line for future research is to apply this conceptual model to other sectors of activity, more or less developed in terms of electronic commerce, which will also access the degree of maturity of the customers of this type of products in different sectors.

Besides identifying the most significant online purchase factors that influence e-customer satisfaction, future research could also make it possible to consider a segmentation approach by type of customer. This would guarantee a better understanding of e-customer’s specificities, allowing for practical actions aimed at their real needs and expectations.

References

Ajzen I (2001) Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):27–58

Ambler T (1997) How much a brand equity is explained by trust? Manag Decis 35(4):283–292

Aminu SA (2012) Empirical investigation of the effect of relationship marketing on banks’ customer loyalty in Nigeria. Interdiscip J Contemp Res Bus 4(6):1249–1267

Anderson R, Srinivasan S (2003) E-satisfaction and e-loyalty: a contingency framework. Psychol Mark 20(2):123–138

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 16(1):74–94

Baker J, Parasuraman A, Grewal D, Voss G (2002) The influence of multiple store environment cues on perceived merchandise value and patronage intentions. J Mark 66(April):120–141

Baumann C, Burton S, Elliott G (2005) Determinants of customer loyalty and share of wallet in retail banking. J Financ Serv Mark 9(3):231–248

Baumgarten H, Homburg C (1996) Applications of structural equation modelling in marketing and consumer research: a review. Int J Res Mark 13(2):139–169

Beatty SE, Smith SM (1987) External search effort: an investigation across several products categories. J Consum Res 14:83–95

Beerli A, Martin JD (2004) Factors influencing destination image. Ann Tour Res 31(3):657–681

Bentler PM, Speckart G (1979) Models of attitude–behavior relations. Psychol Rev 86(5):452–464

Berry L, Seiders K, Grewal D (2002) Understanding service convenience. J Mark 66:1–17

Bettman J, Park C (1980) Effects of prior knowledge and experience and phase of the choice process on consumer decision process: a protocol analysis. J Consum Res 7:234–248

Bloemer J, Ruyter K, Peeters P (1998) Investigating drivers of bank loyalty: the complex relationship between image, service quality and satisfaction. Int J Bank Market 16(7):276–286

Burns D, Krampf R (1992) Explaining innovative behavior: uniqueness-seeking and sensation-seeking. Int J Advert 11(3):227–238

Business2Community (2016) Superb Social Media Marketing Stats Facts, retrieved in March 2016 http://www.business2community.com/social-media/47-superb-social-media-marketing-stats-facts-01431126#F4pzJXrtD0EpmCjG.97

Capon N, Burke M (1980) Individual, product class, and task-related factors in consumer information processing. J Consum Res 7:314–326

Capraro A, Broniarczyk S, Srivastava R (2003) Factors influencing the likelihood of customer defection: the role of consumer knowledge. J Acad Mark Sci 31(2):164–175

Carr N (2001) An exploratory study of gendered differences in young tourists perception of danger within London. Tour Manag 22(5):565–570

Casalo L, Flavian C, Guinaliu M (2008) The role of perceived usability, reputation, satisfaction and consumer familiarity on the website loyalty formation process. Comput Hum Behav 24(2):324–345

Chang HH, Chen S (2009) Consumer perception of interface quality, security, and loyalty in electronic commerce. Inf Manag 46:411–417

Chau V, Ngai L (2010) The youth market for internet banking services: perceptions, attitude and behavior. J Serv Mark 24(1):42–60

Chen W, Lee C (2005) The impact of website image and consumer personality on consumer behavior. Int J Manag 22(3):484–496

Chen Y, Wu JJ, Chang HT (2013) Examining the mediating effect of positive moods on trust repair in e-commerce. Internet Res 23(3):355–371

Childers TL, Carr CL, Peck J, Carson S (2001) Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behavior. J Retail 77(4):511–535

Churchill GA (1979) A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J Mark Res 16(1):64–73

Cole ST, Chancellor HC (2009) Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: an integrated approach. J Vacat Mark 12(2):160–173

Cooil B, Keiningham TL, Aksoy L, Hsu M (2006) A longitudinal analysis of customer satisfaction and share of wallet: investigating the moderating effect of customer characteristics. J Mark 70(4):67–83

Corstjens M, Lal R (2000) Building store loyalty through store brands. J Mark Res 37:281–291

Cronin JJ, Brady MK, Hult G (2000) Assessing the effects of quality, value and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J Retail 76(2):193–218

Cyr D, Hassanein K, Milena H, Ivanov A (2007) The role of social presence in establishing loyalty in e-Service environments. Interact Comput 19:43–56

Danaher P, Mullarkey G, Essegaier S (2006) Factors affecting web site duration: a cross-domain analysis. J Mark Res 43:182–194

Deloitte (2016) The Deloitte Consumer Review: The growing power of Consumers Retrieved 2016, from Deloitte: http://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/consumer-business/consumer-review-8-the-growing-power-of-consumers.pdf

Diener B (2015) 2015 Hotel Industry Trends—from Mobile to Niche Markets. Hotel Online, http://www.hotel-online.com/press_releases/release/2015-hotel-industry-trends-from-mobile-to-niche-markets

Dodds WB, Monroe K, Grewal D (1991) Effects of price, brand and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J Mark Res 28(3):307–319

Doney P, Cannon J (1997) An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. J Mark 61(2):35–51

Donthu N, Garcia A (1999) The internet shopper. J Advert Res 39(3):52–58

East R, Hammond K, Harris P, Lomax W (2000) First-store loyalty and retention. J Mark Manag 16(4):307–325

eMarketeer (2015) Tablet users surpass 1 bilion worldwide, Retrieved from emarketter: http://www.emarketer.com/Article/Tablet-Users-Surpass-1-Billion-Worldwide-2015/1011806

Fiore A, Kim J, Lee HH (2005) Effect of image interactivity technology on consumer responses toward the Online Retailer. J Interact Mark 19(3):38–53

Foster B, Cadogan JW (2000) Relationship Selling and customer loyalty: an empirical investigation. Mark Intell Plan 18(4)

Garbarino E, Johnson M (1999) The different roles of satisfaction, trust and commitment in customer relationships. J Mark 63:70–87

Garbarino E, Strahilevitz M (2004) Gender differences in the perceived risk of buying online and the effects of receiving a site recommendation. J Bus Res 57(7):768–775

Gefen D, Karahanna E, Straub DW (2003) Trust and TAM in online shopping: an integrated model. MIS Q 27(1):51–90

Gilbert G, Veloutsou C (2006) A cross-industry comparison of customer satisfaction. J Serv Mark 20(5):298–308

Govers R (2005) Virtual Tourism Destination Image: glocal identities constructed, perceived and experienced. Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM)

Gremler DD (1995) The effect of satisfaction, switching costs, and interpersonal bonds on service loyalty, doctoral dissertation. Arizona State University, Tempe

Gretzel U, Yoo KH (2008) Use and impact of online travel reviews. Inf Commun Technol Tourism 35–46

Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC (2010) Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall International, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Hassanein K, Head M (2007) Manipulating perceived social presence through the web interface and its impact on attitude towards online shopping. Int J Hum Comput Stud 689–708

Hernandez B, Jimenez J, Martin MJ (2010) Customer behavior in electronic commerce: the moderating effect of e-purchasing experience. J Bus Res 63:964–971

Heung VC (2003) Internet usage by international travellers: reasons and barriers. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 15(7):370–378

Hoffman D, Novak T (2009) Flow online: lessons learned and future prospects. J Interact Mark 23(1):23–34

Homburg C, Menon A (2003) Relationship characteristics as moderators of the satisfaction loyalty link: findings in a business-to-business context. J Bus Bus Mark 10(3):35–62

Hsieh T, Chen YJ (2009) Using the grey relational theory to explore customer relationship management in travel web sites. J Glob Bus Issues 3(1):95–104

Huizingh E (2002) The antecedents of web site performance. Eur J Mark 36(11/12):1225–1247

Im S, Bayus BL, Mason CH (2003) An empirical study of innate consumer innovativeness, personal characteristics, and new product adoption behavior. J Acad Mark Sci 31(1):61–73

Ip C, Law R (2010) Profiling the users of travel websites for planning and online experience sharing. J Hosp Tour Res 24:239–251

James DL, Durand RM, Dreves RA (1976) The use of a multi-attributes attitudes model in a store image study. J Retail 52:23–32

Jin NP, Lee S, Lee H (2015) The effect of experience quality on perceived value, satisfaction, image and behavioral intention of water park patrons: new versus repeat visitors. Int J Tour Res 17:82–95

Jöreskog K, Sörbom D (1996) LISREL 8: structural equation modelling. Scientific Software International, Chicago

Keaveney S, Parthasarathy M (2001) Customer switching behavior in online services: an exploratory study of the role of selected attitudinal, behavioral, and demographic factors. J Acad Mark Sci 29(4):374–390

Kim M, Lennon S (2006) Online service attributes available on apparel retail web sites: an E-S-QUAL approach. Manag Serv Qual 51–77

Kim H, Niehm LS (2009) The impact of website quality on information quality, value, and loyalty intentions in apparel retailing. J Interact Mark 23(3):221–233

Kim DY, Lehto XY, Morrison AM (2007) Gender differences in online travel information search: Implications for marketing communications on the internet. Tour Manag 28(2):423–433

Kim D, Ferrin DL, Rao HR (2009) Trust and satisfaction, two stepping stones for successful e-commerce relationships: a longitudinal exploration. Inf Syst Res 20(2):237–257

Kim W, Di Benedetto C, Lancioni R (2011) The effects of country and gender differences on consumer innovativeness and decision processes in a highly globalized high-tech product market. Asia Pacific J Market Logist 23(5):714–744

Koivumaki T, Svento R, Pertunnen J, Oinas-Kukkonen H (2002) Consumer choice behavior and electronic shopping systems—a theoretical note. Netnomics Econ Res Electron Netw 4:131–144

Koo D-M, Ju S-H (2010) The interactional effects of atmospherics and perceptual curiosity on emotions and online shopping intention. Comput Hum Behav 26:377–388

Kotha S, Venkatachalam M (2004) The role of online buying experience as a competitive advantage: Evidence from third party ratings foe e-commerce firms. J Bus 77(2):100–134

Kumar A, Lim H (2008) Age differences in mobile service perceptions: comparison of generation Y and baby boomers. J Serv Mark 22(7):568–577

Kumar V, Pozza I, Petersen A, Shah D (2009) Reversing the logic: the path of profitability through relationship marketing. J Interact Market 23(2):147

Lai F, Griffin M, Babin B (2009) How quality value, image, and satisfaction create loyalty at a Chinese telecom. J Bus Res 62:980–986

Lepp A, Gibson H (2003) Tourist roles, perceived risk and international tourism. Ann Tour Res 30(3):606–624

Limayem M, Khalifa M, Frini A (2000) What makes consumers buy from internet? A longitudinal study of online shopping. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern A Syst Hum 30(4):421–432

Lo IS, McKercher B, Lo A, Cheung C, Law R (2011) Tourism and online photography. Tour Manag 32(4):725–731

Lu L-C, Chang H-H, Yu S-T (2013) Online shoppers’ perceptions of e-retailers’ ethics, cultural orientation, and loyalty: An exploratory study in Taiwan. Internet Res 23

Macintosh G, Lockshin L (1997) Retail relationships and store loyalty: a multi-level perspective. Int J Res Mark 14(5):487–497

Midgley D, Dowling G (1978) Innovativeness: the concept and its measurement. J Consum Res 4(4):229–242

Morgan R, Hunt S (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J Mark 58(3):20–38

Mostafa R, Wheeler C, Jones M (2006) Entrepreneurial orientation, commitment to the internet and export performance in small and medium sized exporting firms. J Int Entrep 3:291–302

Motorola (2011) Mobility in hospitality: achieving peak efficiency and teamwork to transform the guest experience

Narayandas D, Caravella M, Deighton J (2002) The impact of internet business-to-business distribution. J Acad Mark Sci 30(4):500–505

Oh J, Fiorito S, Cho H, Hofacker C (2008) Effects of design factors on store image and expectation of merchandise quality on web-based stores. J Retail Consum Serv 15:237–249

Oliver R (1981) Measurement and evaluation of satisfaction processes in retail settings. J Retail 57(3)

Oliver R, Burke R (1999) Expectation processes in satisfaction formation: a field study. J Serv Res 16:196–208

Parasuraman A, Berry L, Zeithaml V (1991) Understanding customer expectations of service. Sloan Manag Rev 32(3)

Patterson I (2007) Information sources used by older adults for decision making about tourist and travel destinations. Int J Consum Stud 31(5):528–533

Pitta D, Franzak F, Fowler D (2006) A strategic approach to building online customer loyalty: integrating customer profitability tiers. J Consum Mark 23(7):421–429

Polites GL, Karahanna E (2012) Shackled to the status quo: the inhibiting effects of incumbent system habit, switching costs, and inertia on new system acceptance. MIS Q 36(1):21–42

Rauch R (2014) Top 10 Hospitality Industry Trends in 2015, Hotel, Travel & Hospitality News. http://www.4hoteliers.com/features/article/8736

Reichheld F (2001) Lead for loyalty. Harv Bus Rev 76–84