Abstract

The functioning of representative democracy depends on a “responsible electorate” that rewards and punishes parties according to their promises. Holding representatives accountable is the only way for voters to keep control over the government. This article draws on the normative assumption of accountability theory to investigate the impact of information on pledge fulfillment on citizens’ trust in government, taking into account moderators of this relationship. In a two-wave panel experiment (N = 841; broken pledges, fulfilled pledges, control group), results supported the hypotheses that fulfilled election pledges resulted in increased trust in the government, whereas broken pledges decreased trust. However, only when citizens had been satisfied with the government’s performance in the past or when they attributed relevance to governmental pledge fulfillment did trust levels depend on pledge fulfillment. These findings provide insights into the process of democratic accountability and highlight the relevance of trust in studying the effects of election pledges. Additionally, our study makes a case for the use of repeated measurements in experimental research, as examining intraindividual changes can provide a more comprehensive understanding, such as by assessing effect sizes.

Zusammenfassung

Das Funktionieren repräsentativer Demokratien hängt von einer verantwortungsvollen Wählerschaft ab, die die Parteien gemäß ihren Wahlversprechen bei den nächsten Wahlen belohnt oder bestraft. Die Rechenschaftspflicht der Vertreter*innen ist für die Wählenden die einzige Möglichkeit, die Kontrolle über die Regierung zu behalten. Die vorliegende Studie stützt sich auf die normative Annahme der Accountability Theory, um den Einfluss von Informationen über die Erfüllung von Versprechen auf das Vertrauen der Bürger*innen in die Regierung zu untersuchen – unter Einbeziehung mehrerer moderierender Faktoren. In einem Experiment mit zwei Panelwellen (N = 841; gebrochene Versprechen, erfüllte Versprechen, Kontrollgruppe) stützten die Ergebnisse die Hypothese, dass erfüllte Wahlversprechen zu einem erhöhten Vertrauen in die Regierung führen, während gebrochene Versprechen das Vertrauen verringern. Allerdings hing das Vertrauensniveau nur dann von der Erfüllung der Versprechen ab, wenn die Bürger*innen in der Vergangenheit mit der Leistung der Regierung zufrieden waren oder wenn sie die Information zu gegebenen bzw. gehaltenen Wahlversprechen wichtig fanden. Diese Ergebnisse liefern Einblicke in den Prozess der Verantwortlichkeit in demokratischen Systemen und unterstreichen die Bedeutung von Vertrauen für die Untersuchung der Auswirkungen von Wahlversprechen. Darüber hinaus spricht unsere Studie für die Verwendung messwiederholter Designs in der experimentellen Forschung, da die Untersuchung intraindividueller Veränderungen am besten geeignet ist, um beispielsweise durch die Ermittlung von Effektgrößen ein differenziertes Bild zu liefern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Election pledges play an essential role in democratic persuasion and political representation: Political parties and candidates are elected based on the campaign promises they make to voters (Mansbridge 2003). The elected government’s principal task is then to provide the program-to-policy linkage, that is, to establish “the congruence between the contents of party election manifestos published before elections and subsequent government policy actions” (Thomson 2001, p. 171). Election pledges facilitate that linkage by representing election manifestos in a condensed form. However, for election pledges to play this crucial role in the process of political representation and accountability, trust in the (governing) parties is a necessary prerequisite.

Trust is important in two ways regarding election pledges. First, trust is essential for election pledges’ credibility (Dupont et al. 2016): Voters should trust a party to keep their promises (i.e., trust is the independent variable) if they are inclined to vote for this party, pertaining to trust as “the willingness of a citizen or voter (trustor) to be vulnerable to the actions of this politician (these politicians) (trustee(s)) on the basis of the expectation that this politician (these politicians) will perform particular actions that are important to the citizen/voter, irrespective of the voter’s ability to monitor or control this politician (these politicians)” (Halmburger et al. 2019, p. 238). Second and following from that, a government breaking its promises is expected to experience a decline in credibility and voters’ trust. Vice versa, fulfilled election pledges should increase citizens’ trust (i.e., trust is the dependent variable).

This reasoning also links election pledges to mandate theories of democracy—and most prominent party representation models—that perceive the relationship between voters and parties as a “market-like relation of exchange between producers and customers” (Schedler 1998, p. 194). Accordingly, parties must deliver what they previously offered to fulfill their contractual obligations. Consequently, if parties fail to do so, citizens should incorporate that in their trust ratings of parties, as in Fiorina’s famous “running tally” (Fiorina 1981), and not vote for a party that does not keep its election pledges (hence, is not trustworthy) at future elections. Because of its link to accountability theory, we focus on the effect of broken and kept election pledges on trust in this paper.

Political trust for our study is regarded as the difference between how people think the government should perform and how they evaluate its actual performance (Hetherington and Husser 2012, p. 313) to capture the expectation that election pledges are kept. Moreover, we use the terms “kept “and “fulfilled” as well as “broken” and “unfulfilled” election pledges interchangeably. Additionally, as previous studies pointed toward a complex relationship between governments’ pledge fulfillment and citizens’ assessment thereof (Naurin 2011; van Ryzin 2007; Schofield and Reeves 2015; Thomson 2011), it is important to consider potential moderating factors of this relationship.

To address this research problem, we conducted a two-wave panel experiment with a German electorate quota sample in March 2017. The availability of two waves allowed us to test whether participants’ level of trust in the government changed according to the different pledge information types. More precisely, participants were told that the current government had broken most of its election pledges vs. that it had kept most of its promises. We included several moderators to explore the role of individuals’ predispositions on how they assess information on pledge fulfillment: participants’ party support, satisfaction with the government, the general impression that politicians break their election pledges, and the perceived relevance of the information.

2 Election Pledges in Party Representation

The traditional representation model of “promissory representation” posits that political parties and candidates are elected based on the campaign promises they make to constituents, promises they either keep or break (Mansbridge 2003, p. 515). Although representative systems typically do not bind their incumbents legally to their mandate, the expectation that parties ought to enact their policy program to ensure adequate representation has become the general norm in contemporary democratic theory (Downs 1957; Manin 1997; Pierce 1999; Powell 2000). Moreover, in mandate theories of democracy—and most prominent party representation models—the relationship between voters and parties is perceived as a “market-like relation of exchange between producers and customers” (Schedler 1998, p. 194). Accordingly, parties must deliver what they previously offered to fulfill their contractual obligations. In other words, the assumption is that there is “congruence between the contents of party election manifestos published before elections and subsequent government policy actions” (Thomson 2001, p. 171).

Governments usually implement large parts of their proposed policies (Klingemann et al. 1994; Moury 2011; Moury and Fernandes 2018; Sulkin 2009), on average about 60% (Naurin et al. 2019a; Thomson et al. 2017). Since there are many reasons for not fulfilling election pledges that are out of a government’s control (e.g., economic turmoil, coalition agreements, unforeseen events), this is a rather large portion. However, it leaves about 40% of unfilled/broken election pledges. Thus, electoral accountability models assert that citizens must impose sanctions on government representatives for their past behavior (Manin et al. 1999; Pitkin 1967). A government that failed to act on its election manifesto is expected to be punished (i.e., not reelected) by its constituents. In contrast, a government that has pursued its program is expected to be rewarded (i.e., reelected). It follows that trust should be a key prerequisite for retrospective voting, that is, basing vote choices on the past performance of parties (e.g., Halmburger et al. 2019). However, whereas models on representation that assume an agency relationship between voters and politicians tend to focus on the rational benefits of government performance, they neglect the relevance of citizens’ trust based on pledge fulfillment within accountability processes (e.g., Downs 1957; Fiorina 1981). This study is a first step toward improving the understanding of citizens’ voting considerations by analyzing the impact of election pledge fulfillment on political trust as a prerequisite for the punishment/reward mechanism.

3 Election Pledges and Political Trust

Before the elections, voters find themselves in an uncertain situation. They “know, or should know, that the credibility of those promises is an open question. It is not reasonable on their part to suppose that candidates will necessarily honor their commitments” (Manin 1997, p. 180). However, if voters base their electoral decisions on the political offers parties make, then voters must trust the political parties to keep their promises once they are in government (Dupont et al. 2016). It follows that trust plays an important role in representative democracy, and voters can use information on broken and kept election pledges for their assessments of the trustworthiness of parties (Rose and Wessels 2019). We define political trust as “the ratio of people’s evaluation of government performance relative to their normative expectations of how government ought to perform” (Hetherington and Husser 2012, p. 313). “[T]he general norm, which demands that parties honor their campaign promises, is quite uncontroversial” (Schedler 1998, p. 191). Mansbridge (2003) even refers to promise-keeping as “one of the central principles of democratic theory” (p. 515). Consequently, when a government fulfills its election pledges, constituents’ trust can be expected to increase, simply because this behavior is in line with the general norm. Indeed, citizens prefer reliable and competent parties that offer appropriate policies before taking office (Palmer and Whitten 2002).

On the contrary, broken promises—because they contradict the general norm—can be expected to reduce constituents’ confidence in the party and result in negative evaluations of the incumbent’s reliability and competence. Mainly, broken promises will reduce political trust. These assumptions are also in line with studies investigating the effect of pledge fulfillment on voting. Their results indicate that voters react (at the polls) to party pledge fulfillment and that government parties can prevent electoral losses if they keep their election pledges (Brandenburg et al. 2019; Born et al. 2018; Corazzini et al. 2014; Markwat 2023; Matthieß 2020, 2022). However, the processes underlying the relationship between information on pledge fulfillment and voting behavior remain unclear. Because citizens vote for parties they deem trustworthy (Halmburger et al. 2019), political trust should play a crucial role in this context.

Taken together, our main hypotheses are that information on fulfilling/breaking election pledges affects political trust:

H1a:

Information claiming that a government has broken most of its election pledges decreases people’s trust in the government.

H1b:

Information claiming that a government has fulfilled most of its election pledges increases people’s trust in the government.

However, it is not entirely clear whether both fulfilled and broken election pledges affect citizens’ government evaluations equally. For instance, in a study by Naurin and colleagues (2019b), information on broken election pledges negatively impacted participants’ government evaluations, but fulfilled election pledges had no discernible effect on government evaluations. The authors speak of “asymmetric accountability,” meaning that citizens’ evaluations of government performance were more strongly affected by broken pledges than by fulfilled ones (Naurin et al. 2019b). They attribute this to a general tendency to give greater weight to negative than positive information (e.g., Feldman 1966; Fiske 1980).

This negativity bias also holds for media reporting on pledge fulfillment (Costello and Thomson 2008; Kostadinova 2017). Election pledges are prominently reported in the news media; however, although governments often fulfill more than half of their pledges (e.g., Thomson et al. 2017), newspapers were found to report more on broken than on fulfilled promises across four countries (Müller 2020). Additionally, the media report in an alarmist way about broken pledges (Duval 2019). Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

H2:

Information claiming that a government has broken its election pledges has a stronger effect on people’s trust than information claiming that a government has fulfilled its election pledges.

4 The Moderating Role of Individuals’ Predispositions

In a “real world” context, the relationship between pledge fulfillment and citizens’ trust in their political representatives is complex and conditional on many factors. Many studies have investigated how people process information and how this processing affects people’s subjective perception and interpretation of social reality (e.g., Petty and Cacioppo 1986). Information processing starts with exposure to new information (Bless et al. 2004). During the subsequent internal processing sequence, individuals actively perceive, encode, and categorize the stimulus until they finally judge what the stimulus means. This final judgment of meaning can lead to attitude change. Accordingly, individuals’ predispositions (i.e., attachments, interests, values) and their motivation to process new information (Leeper and Slothuus 2014) can moderate how and to what extent people’s opinion formation differs. We investigated the following potential moderators (some of which are likely correlated), leading to four additional hypotheses: party support, satisfaction with government, the general impression that politicians always break their election pledges, and perceived personal relevance of the information on broken/kept election pledges.

The first three moderators pertain to prior views and expectations, which are also important when it comes to the effects of pledge fulfillment on government assessment (e.g., Markwat 2023). Motivated reasoning theory suggests that people tend to seek out new evidence that is consistent with their prior views (confirmation bias; e.g., Nickerson 1998) and to evaluate attitude-consistent arguments more positively than attitude-inconsistent ones (prior attitude effect; e.g., Kruglanski and Webster 1996; Kunda 1990; Taber and Lodge 2006). We would thus expect that information on fulfilled election pledges is consistent with prior views of supporters of the governing parties, citizens who are satisfied with the government, and citizens who do not think that politicians always break their election pledges. Trust in the government should thus increase in these groups in light of the information on fulfilled election pledges (Bolsen et al. 2014; Duval and Pétry 2020; Pétry and Duval 2017). The intuitive expectation, then, is that trust in the government should decrease in the opposing groups (i.e., citizens who do not support the government, are not satisfied with it, and generally think that politicians always break their election pledges) in light of information on broken election pledges. However, it is important to note that these three moderators are most likely linked to trust. That means that trust in the government will be low for citizens who do not support the government, are not satisfied with it, and generally think that politicians always break their election pledges (e.g., Schuck et al. 2013). Information on broken election pledges could thus not be able to lower trust because it should already be very low. Consequently, we expect a floor effect (Everitt and Skrondal 2010) that translates into no differences between information on broken and kept election pledges for citizens who do not support the government, are not satisfied with it, and think that politicians always break their election pledges. Our hypotheses regarding these three moderators thus are as follows:

H3:

We expect an effect of fulfilled election pledges (compared to broken pledges) on trust for persons who support the governing parties, whereas there will be no differences between broken and fulfilled pledges for those who do not support the governing parties.

H4:

We expect an effect of fulfilled election pledges (compared to broken pledges) on trust for persons who are more satisfied with the government, whereas there will be no differences between broken and fulfilled pledges for those who are less satisfied.

H5:

We expect an effect of fulfilled election pledges on trust (compared to broken pledges) for persons who agree less with the statement that politicians usually break their promises, whereas there will be no differences between broken and fulfilled pledges for those who agree more with the statement that politicians always break their promises.

For our fourth moderator, perceived personal relevance of the information, we turn to a different theoretical argument. Theories on persuasive communication and attitude change assume that the perceived personal relevance of the message content significantly impacts how likely people are to change their opinions, e.g., the elaboration likelihood model (Petty and Cacioppo 1986). According to this model, personal relevance determines the importance of an issue and—in doing so—exerts a powerful effect on memory and leads to a higher elaboration likelihood. Hence, people who perceive information as relevant should be more motivated to scrutinize and elaborate, in light of their existing associations available from memory, on the message’s arguments. That way, they can draw inferences and consequently derive an overall evaluation of the piece of information (Petty and Cacioppo 1986). Moreover, subsequent studies have supported the view that, as personal relevance increases, information processing increases in intensity (e.g., Harkness et al. 1985). In contrast, when personal relevance is low, people should be less motivated to carefully scrutinize the message they receive, meaning that postcommunication attitude change is rather unlikely. Therefore, we expect that pledge fulfillment information will affect citizens’ trust in government only if the information is perceived as personally relevant, hypothesizing that:

H6:

We expect an effect of fulfilled election pledges on trust (compared to broken pledges) for persons who perceive the message on pledge fulfillment as more personally relevant, whereas there will be no differences between broken and fulfilled pledges for those who perceive the message on pledge fulfillment as less personally relevant.

5 The Survey Experiment

The experiment aimed to test the extent to which information about broken or fulfilled election pledges causes intraindividual changes in trust in government. First, we investigated whether information on pledge fulfillment (broken vs. fulfilled election pledges) changes participants’ trust in the government (compared to a control condition). Second, we examined individual factors as potential moderators of this relationship (party support, satisfaction with the government, general impression that politicians always break their promises, and subjectively perceived personal relevance of the information). Therefore, we designed a two-wave panel experiment among German citizens. The advantage of this experimental setup is that it allows—in contrast to studies with only one measurement—analysis of intraindividual opinion changes. This design thus provides substantially more information about the individual change process of trust.

Before this main experiment, we conducted two pre-studies to be able to make informed choices regarding the stimuli and design for the main experiment. In pre-study 1 (N = 268), we explored how information about specific, real-life election pledges that had been broken or fulfilled by the current government affected citizens’ trust. The results of pre-study 1 point to a complex relationship between pledge fulfillment and political trust, at least when news includes detailed information on the number and the content of broken or fulfilled election pledges. Our main conclusion, thus, was to not include any information on the specific pledges in the message on pledge fulfillment used in the experiment below.

In pre-study 2 (N = 470), we tested the effects of media source credibility (quality medium vs. tabloid) and the framing of information about pledge fulfillment (30% of broken election pledges in the negative and 70% of kept election pledges in the positive frame condition). We did not find a significant main effect of the framing of the information on pledge fulfillment on trust in the government. The results, however, suggested that information on pledge fulfillment was perceived as more credible when designed as a quality medium (as opposed to a tabloid one). More detailed information on the pre-studies can be found in the online-only supplement. All the following information pertains to the main experiment.

5.1 The Case: Governments in Germany

Germany is an established democracy with a functioning electoral system, strong parties, identification of about two-thirds of the electorate with a party (Schäfer and Staudt 2019), and election cycles of 4 years on the national level. These characteristics make Germany comparable to other cases where citizens can periodically attribute accountability to the government. However, the German political system is characterized by coalition governments, which means that two or more parties form the government in charge of the country’s executive branch. Thus, as only the coalition government can implement new resolutions, we aimed to investigate the general effect of pledge fulfillment information on citizens’ trust in—and evaluation of—the German federal government at that time as a whole (a coalition of the three parties Christian Democratic Union [CDU], Christian Social Union in Bavaria [CSU], and Social Democratic Party [SPD]).

5.2 Method

The survey was fielded March 8 through March 15, 2017 (wave 1), and March 27 through March 31, 2017 (wave 2). Participants were recruited from the online-access panel Respondi (now Bilendi), which fulfills the quality standards set by the European Society for Opinion and Market Research (esomar.org) and is ISO 26362 certified. We implemented a systematic sampling plan with a quota on sex, age, and education to obtain a sample representative of the German electorate with regard to these variables.

In wave 1, 1068 interviews were completed. After cleaning the data due to screenout of persons who were not eligible to vote in the upcoming federal election, quota full, or participant withdrawal from the study, wave 1 included 1016 participants. In wave 2, 841 of them participated again. Thus, the final sample included 841 persons between 18 and 86 years of age (M = 52.63, SD = 15.22), all of whom were German citizens and had the right to vote in the German federal election in September 2017. Of this sample, 49% identified as female and 51% as male. In terms of education, 41% had a low educational background, 27% had an intermediate educational background, and 32% had a high educational background.

We used a 2 × 3 (time: wave 1, wave 2) × (information on pledge fulfillment: treatment “broken election pledges,” treatment “fulfilled election pledges,” control group) factorial design with repeated measures of trust in government. Time was a within-subject factor. The between-subjects factor consisted of three conditions participants were randomly assigned to in wave 2. Throughout the present paper, significance tests were conducted with α = 0.05.

In condition 1, participants received information that the current government had broken many of its election pledges. The news headline was (translated): “Many election pledges have been broken,” followed by a short outline of the article (translated): “… It is time to take stock. Did the federal government work reliably or did it break its election pledges? Our analysis shows: Most election pledges have been broken …” In condition 2, participants were told that the current government had fulfilled many of its election pledges. Respondents were shown the same introductory text as in condition 1, but the word broken was replaced by the word fulfilled. The third condition aimed to function as a control condition to shed light on the driving effects contrasting the fulfilled-pledges vs. the broken-pledges condition. In this condition, respondents did not receive information on pledge fulfillment or any other treatment.Footnote 1

Based on the findings of pre-study 1, to avoid pledge content affecting the treatment outcomes, we did not include any information on the specific pledges in the message on pledge fulfillment used in the experiment. This way, we could obtain a clearer picture of the widespread impact that election pledge fulfillment has on trust in the government. The texts, although fictitious, were realistic in the sense that with the federal election in Germany taking place half a year after the data were collected, information on pledge fulfillment was to be expected. Moreover, since there often is disagreement regarding to what degree governments fulfilled their election pledges, the conclusions of both treatments are plausible. To promote treatment credibility and take account of the results of pre-study 2, the treatment message layout was inspired by the graphical style of Spiegel.de, the online platform of a popular German quality newspaper.

To measure the dependent variable trust in the government in wave 1 and wave 2, we conceptualized trust as a multidimensional concept (Connelly et al. 2015) and asked participants how they perceived politicians of the government regarding competence and integrity. This fits our definition of trust as “the ratio of people’s evaluation of government performance relative to their normative expectations of how government ought to perform” (Hetherington and Husser 2012, p. 313) since the normative expectation should be that politicians are high in competence and integrity. Values lower than the maximum of the scale can thus be regarded as actual performance ratings relative to the normative expectation. For each of the two trust subscales, integrity and competence, we used three items each from Halmburger and colleagues’ (2019) trust-in-politicians scale (adapted to trust in politicians of the current government) and computed an overall mean score. We excluded the third subscale (benevolence), as the results of pre-study 1 revealed that information on pledge fulfillment primarily affected integrity and competence. Participants were asked to evaluate the current German federal government of CDU/CSU and SPD regarding its integrity (attribution to the trustee being fair, just, and reliable, e.g., “Politicians of the current federal government act responsibly”) and competence (attribution to the trustee being able to solve problems successfully, e.g., “Politicians of the current federal government are sufficiently competent”; see the online supplement). A five-point Likert-type scale was used, ranging from 1 (do not agree) to 5 (fully agree; Cronbach’s α = 0.93 [wave 1] and α = 0.92 [wave 2]).

As a proxy for party support, we used respondents’ voting intentions concerning the upcoming election (e.g., Fiorina 1981). In wave 1, we asked participants which party they would vote for at the next federal elections on September 24, 2017 (CDU/CSU, SPD, the Left, the Greens, the Free Democratic Party, Alternative for Germany, other, “I do not know,” “I will cast a blank vote,” “I do not intend to go to the polls”). Dichotomizing the variable, party supporters (0.5) were those respondents who said they would vote for at least one of the then governing parties (CDU/CSU, SPD), and nonsupporters (−0.5) were all other participants. To measure satisfaction with the government (wave 1), we used an item well established in German survey research: “Thinking about the federal government of CDU/CSU and SPD in Berlin, how satisfied are you—by and large—with the way it is doing its job?” (1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied). To measure whether respondents had the impression that politicians always break their promises, we asked them to what extent they agreed with the statement “Election pledges are never kept” (1 = do not agree at all to 5 = fully agree). Finally, to test whether perceived personal relevance of the information presented during the experiment would affect findings, we asked whether the shown information on pledge fulfillment was personally relevant to them (1 = does not apply to me at all to 5 = fully applies to me). Since we cannot know why and which part of the information respondents found personally relevant (or not), and with our treatments not mentioning the content of the fulfilled or broken election pledges, we opted for this general measure of personal relevance.

Participants were told that the study was designed to explore people’s opinions on politics in Germany. In wave 1, they were instructed to fill in the questionnaire (see the online supplement). Two weeks later, in wave 2, the same people were invited to participate in the follow-up study consisting of the treatment and a posttest questionnaire. They were randomly assigned to the conditions and instructed to carefully read the news report about the extent of the current government’s pledge fulfillment (see the online supplement). Upon completing the questionnaire, participants were thanked and debriefed by clarifying that the article they had read was completely fictitious. To ensure that this information also reached participants who broke off the second interview, the survey institute informed these participants via email.

6 Results

6.1 Main Effect Analysis

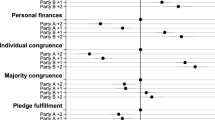

Table 1 provides an overview of the results of all hypotheses tests. Regarding H1a, H1b, and H2, we ran a two-way 2 × 3 (time: wave 1, wave 2) × (information on pledge fulfillment: broken pledges, fulfilled pledges, control group) mixed analysis of variance of trust with repeated measures of the first factor. This analysis yielded a statistically significant interaction of information on pledge fulfillment and time, F(2, 824) = 9.13, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.02, illustrated in Fig. 1.

Results of a two-way 2 × 3 (time: wave 1, wave 2) × (information on pledge fulfillment: treatment “broken election pledges,” treatment “fulfilled election pledges,” control group) mixed analysis of variance on trust, with repeated measures on time. The figure shows the means of trust in the government for each condition by time. Statistically significant differences are marked as follows: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01

Simple effects tests yielded a significant difference in trust between wave 1 and wave 2 within each experimental condition. In the broken-election-pledges condition, trust in the government declined: MTrust_Wave 1 = 2.81, SE = 0.06, MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.72, SE = 0.06, F(1, 824) = 4.74, p = 0.030, ηp2 = 0.01. By contrast, in the fulfilled-pledges condition, trust in the government increased: MTrust_Wave 1 = 2.78, SE = 0.06, MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.92, SE = 0.06, F(1, 824) = 11.03, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.01. In the control group, we found no statistically significant change in trust levels: MTrust_Wave 1 = 2.92, SE = 0.06, MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.85, SE = 0.06, F(1, 824) = 2.66, p = 0.103. Further, in wave 2, the means of the three groups differed significantly: F(2, 824) = 3.10, p = 0.045, ηp2 = 0.01. This effect can be traced back to the fact that in the fulfilled-pledges condition, trust was significantly higher than in the broken-pledges condition (Bonferroni-corrected p = 0.046).

In general, the results supported our main hypotheses that information on broken election pledges decreased trust in the government (H1a), whereas information on fulfilled election pledges increased trust in the government (H1b). Contrary to H2, the results did not support the assumption of asymmetry in accountability processes: The effect of the broken-pledges condition on trust was similar to the fulfilled-pledges condition’s effect. Effect sizes were small, potentially pointing to the role of moderating factors.

6.2 Moderation Analyses

Moderation analyses contrasted the broken-pledges condition (coded as −0.5) with the fulfilled-pledges condition (coded as 0.5) as the independent variable.Footnote 2 We used trust in government in wave 2 as the dependent variable and inserted trust in government in wave 1 as a covariate. In turn, we probed the moderator variable’s effect by testing the conditional effects via the pick-a-point approach (Rogosa 1980). According to this approach, the significance of X’s effect is tested at three fixed values of the moderator, that is, at the mean, +1 SD, −1 SD (except for party support since this is a dichotomous variable). Preconditions for linear regression analyses were tested and fulfilled (including homoscedasticity, normal distribution, and independence of residuals). The mean values of trust in the government (wave 1, wave 2) for values of the moderator variables are illustrated in the online supplement (Table C4). We found no indication that multicollinearity contaminated the results (Table C5).

H3: Party Support

Contrary to H3, party support was not a significant moderator of the effect of news about pledge fulfillment on government trust, F(1, 549) < 1, p = 0.999 (R2 = 0.61; ∆R2 = 0.00). Among both supporters and nonsupporters of a government party, trust levels were significantly higher after the presentation of information on fulfilled election pledges as opposed to information on broken election pledges: For government supporters in the broken-pledges condition, MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.80, and in the fulfilled-pledges condition, MTrust_Wave 2 = 3.03 (b = 0.23, t(549) = 2.94, p = 0.003); for nonsupporters in the broken-pledges condition, MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.63, and in the fulfilled-pledges condition, MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.86 (b = 0.23, t(549) = 3.16, p = 0.002). The interaction plots for H3 to H6 are illustrated in Fig. 2.

H4: Satisfaction with Government

In line with H4, respondents’ satisfaction with the government significantly moderated the effect of pledge fulfillment news on government trust: F(1, 549) = 4.59, p = 0.033 (R2 = 0.64, ∆R2 = 0.01). Respondents exposed to information on fulfilled election pledges showed higher trust in the government than respondents in the broken-pledges condition when they were moderately satisfied (M = 2.47, SE = 0.05; broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.71; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.94; b = 0.24, t(549) = 4.69, p < 0.001) or highly satisfied (+1 SD = 3.54, SE = 0.07; broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.90; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 3.24; b = 0.35, t(549) = 4.81, p < 0.001). Among people with low government satisfaction (−1 SD = 1.39, SE = 0.07; broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.52; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.65), trust did not significantly depend on the information received: b = 0.13, t(549) = 1.81, p = 0.072. More precisely, the Johnson–Neyman technique (Johnson and Neyman 1936) revealed a statistically significant conditional effect of pledge-fulfillment information on trust for participants with government satisfaction values of 1.46 or higher on a scale ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction), applying to 75% of the sample. Accordingly, only for people with very low government satisfaction did trust not depend on information on pledge fulfillment.

H5: Impression that Politicians Break Their Promises

Contrary to H5, we found no significant moderation effects of respondents’ impression that politicians break their promises on trust in government: F(1, 549) = 1.11, p = 0.292 (R2 = 0.62; ∆R2 = 0.00). In all groups, trust levels were higher in the fulfilled than in the broken election pledges condition: among participants who did not assume that politicians usually break their promises (−1 SD = 2.43, SE = 0.07; broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.87; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 3.03; b = 0.16, t(549) = 2.18, p = 0.029); among those who were rather indifferent (M = 3.55, SE = 0.05; broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.71; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.93; b = 0.22, t(549) = 4.18, p < 0.001); and among participants who assumed that politicians usually break their promises (+1 SD = 4.67, SE = 0.07, broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.56; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.83; b = 0.27, t(549) = 3.68, p < 0.001).

H6: Perceived Personal Relevance

In line with H6, an additional multiple regression analysis showed that perceived personal relevance of the received news moderated the effects of information about pledge fulfillment on trust in government: F(1, 549) = 20.74, p < 0.001 (R2 = 0.62, ∆R2 = 0.01). Simple slopes analyses indicated that participants exposed to fulfilled election pledges showed higher trust in the government than those in the broken-pledges condition when they perceived the information regarding pledge fulfillment as moderately relevant (M = 3.23, SE = 0.05; broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.72; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.96; b = 0.24, t(549) = 4.51, p < 0.001) or as highly relevant (+1 SD = 4.52, SE = 0.08; broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.66; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 3.15; b = 0.49, t(549) = 6.33, p < 0.001). In contrast, people who perceived the information as less relevant (−1 SD = 1.95, SE = 0.08) did not differ in their level of trust in the government after receiving the information on broken or kept election pledges (broken-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.78; fulfilled-pledges condition: MTrust_Wave 2 = 2.76; b = −0.02, t(549) = −0.29, p = 0.771). According to the Johnson–Neyman technique, the conditional effect of pledge-fulfillment information on trust was significant when respondents’ personal relevance was 2.63 or higher on a scale ranging from 1 (low relevance) to 5 (high relevance), applying to 74% of the sample. In line with our expectations, the information did not substantially affect trust among people who attributed little relevance to it.

7 Conclusion

This research examined the relationship between pledge fulfillment and trust in the government. Our main findings support the normative assumption of accountability theory (see Table 1 for an overview of findings) that fulfilled election pledges increase trust in the government among participants, whereas broken pledges decrease respondents’ trust. However, our results do not support previous findings on asymmetric accountability (Naurin et al. 2019b). In our study, the effect sizes of both broken and fulfilled election pledges were similar.

With regard to moderation analyses, we found that information on broken vs. fulfilled election pledges affected only participants with a medium or high satisfaction with the government. Moreover, perceived personal relevance of the message’s content mattered in terms of how participants processed information on pledge fulfillment. Only when the perceived relevance was average or high did trust in the government differ significantly between participants who received information about fulfilled pledges and participants who received information about broken pledges.

Against expectations, party support did not moderate the effect of the information given because supporters and nonsupporters both showed higher trust after receiving information on fulfilled election pledges as opposed to those who read information on broken pledges. Accordingly, our results did not support the assumption that fulfilled election pledges negatively impact nonsupporters’ government evaluations (Naurin et al. 2019b) or that supporters do not react to broken election pledges. One reason for this could be that supporters of the government explicitly support it for its policies and are thus directly affected and disappointed if the government does not keep its pledges. This should be further investigated, such as by testing the impact of single broken or fulfilled election pledges on trust and exploring the role of party or policy consistency (see Naurin et al. 2019b) as moderators.

Additionally, we found no support for the hypothesis that individuals who believe politicians are likely to break election pledges are immune to information about fulfilled or broken election pledges. One reason could be that individuals do not apply the widespread “stereotype” of the pledge-breaking politician (Thomson and Brandenburg 2019) to the current government because they find reasons for a specific government or politician to not keep their pledges. Another reason could be that even though we expect political trust to be very low with citizens who think that politicians always break their election pledges, there is still room for it to decline. This would be in line with the results of Matthieß (2022), who showed that mistrusting citizens punish pledge-breaking more severely than trusting citizens.

One limitation of our study is that the experimental design helped to ensure internal validity, albeit at the expense of external validity. In Germany, coalition governments are the norm. This institutional setting makes it quite difficult for citizens to blame or reward the “responsible” party in the context of specific political action (Sulitzeanu-Kenan and Zohlnhöfer 2019). In light of this, the question of whether citizens can hold coalition parties separately accountable for their fulfillment of election pledges (i.e., by virtue of party identification or party sympathy) calls for emphasis. Our pragmatic decision to not differentiate between the governing parties in our treatment could lead participants to think about reasons why all three coalition partners were (un)successful in keeping their election pledges. Future research should take this into account and also corroborate our findings within other government types. Second, in terms of communication, source credibility may affect citizens’ processing of information on pledge fulfillment (see also the results of pre-study 2 in the online supplement). We used the design of a high-quality news outlet as the source for pledge-fulfillment information to avoid tampering with the message’s credibility. However, because various news channels provide information on government performance, more research on the relationship between different sources (e.g., traditional and new media) and citizens’ processing of political information is needed (for an overview, see, e.g., Hefner et al. 2018). In general, there is considerable need for research on the subject of media coverage on pledge fulfillment (Kostadinova 2017, 2019) and for experimental studies testing whether and how biases in the dissemination of information (i.e., timing, saliency, negativity biases) as well as cognitive biases (e.g., the recency effect; Jones and Goethals 1972) influence citizens’ perception of election pledge fulfillment.

Third, too little attention has been paid to the question of how attributions shape citizens’ evaluations of government performance. This study’s results suggest that people tend to attribute the causes of government performance in terms of pledge fulfillment, at least in part, to internal factors (“individual” characteristics and traits such as competence and integrity of the governing parties). However, it remains unclear whether and under what circumstances citizens take external factors (e.g., situational forces) into account when evaluating the political outcome since, in some circumstances, not keeping election pledges is reasonable to politicians and citizens (e.g., in times of economic turmoil or in the face of unforeseen events such as a pandemic). More research is needed to understand the underlying processes and biases that lead to our inferences about the causes of government performance.

Despite these limitations, our study highlights that citizens react to general information on pledge fulfillment by withdrawing or exalting trust in the government. Against the background of voter mobilization and electoral marketing, this has practical implications. Although we did not find evidence for asymmetric accountability, the results of previous studies that the media give increasingly more weight to broken pledges (e.g., Müller 2020) are alarming in combination with our finding that news on broken pledges decreases trust in the government. Additionally, political trust is also a prerequisite for perceiving election pledges as credible (Dupont et al. 2016) and perceiving pledge fulfillment accurately (Pétry and Duval 2017). Hence, even though most election pledges are kept, biased reporting in favor of broken election pledges could stimulate a vicious circle of decreasing trust in governments. However, the opposite is also possible—a strengthening of trust—if citizens are accurately informed about pledge fulfillment. Our findings thus provide insights into the process of democratic accountability and highlight the relevance of trust in studying the effects of election pledges.

Notes

Since the wording of the measure is not related to the treatment, this does not result in a problem with measuring the dependent variable. We also did not find significant pretreatment differences between the three groups regarding evaluations of pledge fulfillment: The mean of the combined questions from wave 1, “On the whole the CDU/CSU [resp. SPD] has fulfilled the larger part of their election pledges” (1 = do not agree at all, 5 = totally agree), is 2.60 in condition 1, 2.55 in condition 2, and 2.61 in condition 3.

We performed moderation analyses using PROCESS version 3.4 for SPSS (Hayes 2017) to test our moderation hypotheses (H3–H6) using linear regressions.

References

Bless, Herbert, Klaus Fiedler, and Fritz Strack. 2004. Social cognition: how individuals construct social reality. Hove: Psychology Press.

Bolsen, Toby, James N. Druckman, and Fay Lomax Cook. 2014. The influence of partisan motivated reasoning on public opinion. Political Behavior 36:235–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9238-0.

Born, Andreas, Pieter van Eck, and Magnus Johannesson. 2018. An experimental investigation of election promises. Political Psychology 39:685–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12429.

Brandenburg, Heinz, Fraser McMillan, and Robert Thomson. 2019. Does it matter if parties keep their promises? The impact of voter evaluations of pledge fulfilment on vote choice. APSA Preprint https://doi.org/10.33774/apsa-2019-p13l5.

Connelly, Brian L., T. Russell Crook, James G. Combs, David J. Ketchen, and Herman Aguinis. 2015. Competence- and integrity-based trust in interorganizational relationships: which matters more? Journal of Management 44:919–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315596813.

Corazzini, Luca, Sebastian Kube, Michel André Maréchal, and Antonio Nicolò. 2014. Elections and deceptions: an experimental study on the behavioral effects of democracy. American Journal of Political Science 58:579–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12078.

Costello, Rory, and Robert Thomson. 2008. Election pledges and their enactment in coalition governments: a comparative analysis of ireland. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 18:239–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457280802227652.

Downs, Anthony. 1957. An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of Political Economy 65:135–150.

Dupont, Julia C., Evelyn Bytzek, Melanie C. Steffens, and Frank M. Schneider. 2016. Die Bedeutung von politischem Vertrauen für die wahrgenommene Glaubwürdigkeit von Wahlversprechen. Politische Psychologie 5:5–27.

Duval, Dominic. 2019. Ringing the alarm: The media coverage of the fulfillment of election pledges. Electoral Studies 60:102041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2019.04.005.

Duval, Dominic, and Francois Pétry. 2020. Citizens’ evaluations of campaign pledge fulfillment in Canada. Party Politics 6:437–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818789968.

Everitt, Brian, and Anders Skrondal. 2010. The Cambridge dictionary of statistics, 4th edn., Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Feldman, Shel. 1966. Motivational aspects of attitudinal elements and their place in cognitive interaction. In Cognitive consistency: motivational antecedents and behavioral consequents, ed. Shel Feldman, 75–108. New York: Academic Press.

Fiorina, Morris P. 1981. Retrospective voting in American national elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fiske, Susan T. 1980. Attention and weight in person perception: the impact of negative and extreme behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 38:889–906. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.38.6.889.

Halmburger, Anna, Tobias Rothmund, Anna Baumert, and Jürgen Maier. 2019. Trust in politicians—understanding and measuring the perceived trustworthiness of specific politicians and politicians in general as multidimensional constructs. In Wahrnehmung – Persönlichkeit – Einstellungen. Psychologische Theorien und Methoden in der Wahl- und Einstellungsforschung, ed. Evelyn. Bytzek, Ulrich Rosar, and Markus Steinbrecher, 235–302. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Harkness, Allan R., Kenneth G. DeBono, and Eugene Borgida. 1985. Personal involvement and strategies for making contingency judgments: a stake in the dating game makes the difference. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49:22–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.49.1.22.

Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Methodology in the social sciences. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach, 2nd edn., New York: Guilford.

Hefner, Dorothée Eike Mark Rinke, and Frank M. Schneider. 2018. The POPC citizen: Political information processing in the fourth age of political communication. In Permanently online, permanently connected. Living and communicating in a POPC world, ed. Peter Vorderer, Dorothée Hefner, Leonard Reinecke, and Christoph Klimmt, 199–207. New York: Routledge.

Hetherington, Marc J., and Jason A. Husser. 2012. How trust matters: the changing political relevance of political trust. American Journal of Political Science 56:312–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00548.x.

Johnson Palmer, Oliver, and Jerzy Neyman. 1936. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their applications to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs 1:57–93.

Jones, Edward E., and George R. Goethals. 1972. Order effects in impression formation: Attribution context and the nature of the entity. In Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior, ed. Edward E. Jones, David E. Kanouse, Harold H. Kelly, Richard E. Nisbett, Stuart Valins, and Bernard Weiner, 27–46. Morristown: General Learning Press.

Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, Richard I. Hofferbert, and Ian Budge. 1994. Parties, policies and democracy. Boulder: Westview Press.

Kostadinova, Petia. 2017. Party pledges in the news: which election promises do the media report? Party Politics 23:636–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815611649.

Kostadinova, Petia. 2019. Influential news: impact of print media reports on the fulfillment of election promises. Political Communication 36:412–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2018.1541032.

Kruglanski, Arie W., and Donna M. Webster. 1996. Motivated closing of the mind: “Seizing” and “freezing”. Psychological Review 103:263–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.103.2.263.

Kunda, Ziva. 1990. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin 108:480–498. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480.

Leeper, Thomas J., and Rune Slothuus. 2014. Political parties, motivated reasoning, and public opinion formation. Advances in Political Psychology 35:129–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12164.

Manin, Bernard. 1997. The principles of representative government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Manin, Bernard, Adam Przeworski, and Susan C. Stokes. 1999. Elections and representation. In Democracy, accountability, and representation, ed. Adam Przeworski, Susan C. Stokes, and Bernard Manin, 29–54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mansbridge, Jane. 2003. Rethinking representation. American Political Science Review 97:515–528. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055403000856.

Markwat, Niels. 2023. Not as expected: the role of performance expectations in voter responses to election pledge fulfilment. European Political Science 22:308–324. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-023-00415-y.

Matthieß, Theres. 2020. Retrospective pledge voting: A comparative study of the electoral consequences of government parties’ pledge fulfilment. European Journal of Political Research 59:774–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12377.

Matthieß, Theres. 2022. Retrospective pledge voting and mistrusting citizens: evidence for the electoral punishment of pledge breakage from a survey experiment. Electoral Studies 80:102547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2022.102547.

Moury, Catherine. 2011. Italian coalitions and electoral promises: assessing the democratic performance of the Prodi I and Berlusconi II governments. Modern Italy 16:35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2010.481090.

Moury, Catherine, and Jorge Fernandes. 2018. Minority governments and pledge fulfilment: evidence from Portugal. Government and Opposition 53:335–355. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.14.

Müller, Stefan. 2020. Media coverage of campaign promises throughout the electoral cycle. Political Communication 37:696–718. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1744779.

Naurin, Elin. 2011. Election promises, party behaviour and voter perceptions. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Naurin, Elin, Terry J. Royed, and Robert Thomson. 2019a. Party mandates and democracy. Making, breaking, and keeping election pledges in twelve countries. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Naurin, Elin, Stuart Soroka, and Niels Markwat. 2019b. Asymmetric accountability: an experimental investigation of biases in evaluations of governments’ election pledges. Comparative Political Studies 52:2207–2234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414019830740.

Nickerson, Raymond S. 1998. Confirmation bias: a ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology 2:175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175.

Palmer, Harvey D., and Guy D. Whitten. 2002. Economics, politics, and the cost of ruling in advanced industrial democracies. In Economic voting, ed. Han Dorussen, Michael Taylor, 66–91. London: Routledge.

Pétry, Francois, and Dominic Duval. 2017. When heuristics go bad: Citizens’ misevaluations of campaign pledge fulfilment. Electoral Studies 50:116–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2017.09.010.

Petty, Richard E., and John T. Cacioppo. 1986. The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 19, ed. Leonard Berkowitz, 123–205. New York: Academic Press.

Pierce, Roy. 1999. Masselite issue linkages and the responsible party model of representation. In Policy representation in Western Europe, ed. Warren E. Miller, Roy Pierce, Jaques Thomassen, Richard Herrera, Sören Holmberg, Peter Esaiasson, and Bernhard Wessels, 9–32. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pitkin, Hanna F. 1967. The concept of representation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Powell Bingham, G. 2000. Elections as instruments of democracy. Majoritarian and proportional visions. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Rogosa, David. 1980. Comparing nonparallel regression lines. Psychological Bulletin 88:307–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.2.307.

Rose, Richard, and Bernhard Wessels. 2019. Money, sex and broken promises: politicians’ bad behaviour reduces trust. Parliamentary Affairs 72:481–500. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsy024.

Schäfer, Anne, and Alexander Staudt. 2019. Parteibindungen. In Zwischen Polarisierung und Beharrung: Die Bundestagswahl 2017, ed. Sigrid Roßteutscher, Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, Harald Schoen, Bernhard Weßels, and Christof Wolf, 207–217. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Schedler, Andreas. 1998. The normative force of electoral promises. Journal of Theoretical Politics 10:191–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692898010002003.

Schofield, Peter, and Peter Reeves. 2015. Does the factor theory of satisfaction explain political voting behaviour? European Journal of Marketing 45:968–992. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-08-2014-0524.

Schuck, Andreas R.T., Hajo G. Boomgaarden, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2013. Cynics all around? The impact of election news on political cynicism in comparative perspective. Journal of communication 63:287–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12023.

Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Raanan, and Reimut Zohlnhöfer. 2019. Policy and blame attribution: citizens’ preferences, policy reputations, and policy surprises. Political Behavior 41:53–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-017-9441-5.

Sulkin, Tracy. 2009. Campaign appeals and legislative action. The Journal of Politics 71:1093–1108. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381609090902.

Taber, Charles S., and Milton Lodge. 2006. Motivated scepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science 50:755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x.

Thomson, Robert. 2001. The programme to policy linkage: the fulfilment of election pledges on socio-economic policy in the Netherlands, 1986–1998. European Journal of Political Research 40:171–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00595.

Thomson, Robert. 2011. Citizens’ evaluations of the fulfillment of election pledges: evidence from Ireland. The Journal of Politics 73:187–201. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381610000952.

Thomson, Robert, and Heinz Brandenburg. 2019. Trust and citizens’ evaluations of promise keeping by governing parties. Political Studies 67:249–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321718764177.

Thomson, Robert, Terry Royed, Elin Naurin, Joaquin Artés, Rory Costello, Laurenz Ennser-Jedenastik, Mark Ferguson, Petia Kostadinova, Catherine Moury, Francois Pétry, and Katrin Praprotnik. 2017. The fulfillment of parties’ election pledges: a comparative study on the impact of power sharing. American Journal of Political Science 61:527–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12313.

Van Ryzin, Gregg G. 2007. Pieces of a puzzle: Linking government performance, citizen satisfaction, and trust. Public Performance & Management Review 30:521–535. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576300403.

Acknowledgements

We thank Natalia Bogado, Julia Schnepf, Anders Larrabee Sønderlund, and Christophe Becht for valuable comments and language editing.

Funding

This research was supported by a research grant from the research focus Communication, Media, & Politics within the research initiative of Rhineland-Palatinate, at the University of Koblenz-Landau (now University of Kaiserslautern-Landau), Germany.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

E. Bytzek, J.C. Dupont, M.C. Steffens, N. Knab, and F.M. Schneider declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

11615_2024_567_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

The supplementary information contains: Prestudy 1, prestudy 2, and additional information on the main experiment (treatment materials, question wordings, means and correlations of variables).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bytzek, E., Dupont, J.C., Steffens, M.C. et al. Do Election Pledges Matter? The Effects of Broken and Kept Election Pledges on Citizens’ Trust in Government. Polit Vierteljahresschr (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-024-00567-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11615-024-00567-6