Abstract

Background

Veterans receiving care within the Veterans Health Administration (VA) are a unique population with distinctive cultural traits and healthcare needs compared to the civilian population. Modifications to evidence-based interventions (EBIs) developed outside of the VA may be useful to adapt care to the VA healthcare system context or to specific cultural norms among veterans. We sought to understand how EBIs have been modified for veterans and whether adaptations were feasible and acceptable to veteran populations.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of EBI adaptations occurring within the VA at any time prior to June 2021. Eligible articles were those where study populations included veterans in VA care, EBIs were clearly defined, and there was a comprehensive description of the EBI adaptation from its original context. Data was summarized by the components of the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based interventions (FRAME).

Findings

We retrieved 922 abstracts based on our search terms. Following review of titles and abstracts, 49 articles remained for full-text review; eleven of these articles (22%) met all inclusion criteria. EBIs were adapted for mental health (n = 4), access to care and/or care delivery (n = 3), diabetes prevention (n = 2), substance use (n = 2), weight management (n = 1), care specific to cancer survivors (n = 1), and/or to reduce criminal recidivism among veterans (n = 1). All articles used qualitative feedback (e.g., interviews or focus groups) with participants to inform adaptations. The majority of studies (55%) were modified in the pre-implementation, planning, or pilot phases, and all were planned proactive adaptations to EBIs.

Implications for D&I Research

The reviewed articles used a variety of methods and frameworks to guide EBI adaptations for veterans receiving VA care. There is an opportunity to continue to expand the use of EBI adaptations to meet the specific needs of veteran populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND

Evidence-based interventions (EBIs) are often implemented in settings different from those in which they were originally developed and are frequently adapted to better meet the needs of the novel setting and/or population. Adaptations have been defined as modifying programs or practices, usually in a planned or thoughtful way.1,2,3,4,5 Such modifications are typically intended to improve the feasibility, compatibility, acceptability, and/or effectiveness of an EBI for use in specific contexts (e.g., community, political, religious),6 to better reflect cultural or societal norms,7 to provide refinements for a different population than originally intended, or to meet the requirements of system-level constraints2. Adaptations may be developed during study design, prior to study start, or may occur during the intervention based on feedback or need,2 and, when successful, can lead to improved reach, acceptability, and sustainability of the EBI.

The importance of adapting EBIs to specific populations—such as veterans—has been well-documented.1,8 According to Rogers9, adaptations are needed as “innovation almost never fits perfectly in the organization in which it is being embedded” and having “organizations and stakeholders involved in the implementation process” can help “optimize fit and maximize effectiveness” of an EBI.10 As the use of adaptations of EBIs becomes more popular within the field of implementation science,1 a growing body of literature has suggested that developing strategies to document such adaptations is needed. Specifically, Chambers and Norton11 argue for an “adaptome” that systematically documents variations and adaptations for intervention developers and the implementation science research community. Similarly, the expanded Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based interventions (FRAME) offers a framework for characterizing and coding adaptations to EBIs.2 The use of FRAME can facilitate a structured approach to document the implementation of EBIs, with details on when and why modifications were made to the original intervention, as well as reasons for the modifications.

Adaptations to EBIs implemented for US veterans may be especially warranted. Over 9 million veterans receive care within the Veterans Health Administration (VA), the largest integrated healthcare system in the USA.12 Veterans are a unique population with geographic distribution throughout the country. Nearly 1/3 of veterans are members of a racial or ethnic minority group, with women veterans representing the most diverse group of veterans.13 EBIs may be useful for the veteran population given their distinctive cultural traits, such as core military values (e.g., loyalty, duty, integrity) and experiences of military culture including language (e.g., military lingo), uniforms, specific sets of rules and regulations, and hierarchical structure (e.g., rank, chain of command, specialty).14,15,16 Furthermore, veterans have higher rates of mental health disorders, substance-use disorders, suicide, homelessness, and other chronic physical health conditions compared to civilians.17 Modifications to EBIs developed outside of the VA, or for particular subgroups of veterans, may be useful to adapt care to match the VA healthcare system context, to specific veteran cultural norms, or to account for high rates of comorbidity within the VA setting.

Given that veterans are a unique population with distinctive cultural traits, have higher rates of mental and physical health conditions compared to civilians, and receive healthcare within a veteran-specific context, adaptations to EBIs developed outside of the VA healthcare system or for different subsamples of the veteran population (e.g., women veterans) may facilitate better outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, no previous review has documented studies with adaptations to EBIs for the VA setting or for specific subgroups of veterans. Therefore, the objective of this scoping review was to document adaptations to EBIs occurring within the VA, to examine how adaptations were done within the VA context, and to explore whether EBI adaptations were feasible to implement and/or acceptable to veterans.

METHODS

We conducted a scoping review of EBI adaptations occurring within the VA at any point prior to June 2021. As our goal was to examine key concepts in this research area, we opted for a scoping review to conduct a broad overview and capture data on studies that used different research designs, data collection techniques, and data analysis procedures.18,19

Search Strategy

We conducted our initial search in PubMed/MEDLINE where we extracted the full search terms (including MeSH terms) and conducted subsequent searches using the full search terms in CINAHL and PsycInfo (see Appendix for search terms). Search terms included (but were not limited to) adaptation, tailored, intervention, evidence-based, and Veterans Health Administration.

Data Abstraction

Criteria for sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and research type (SPIDER) were developed to guide our inclusion and exclusion criteria.20 SPIDER is often used in evaluating both quantitative and qualitative research and thus we chose to use this model to develop our eligibility criteria.21 The SPIDER criteria identified articles with (1) study populations including veterans in VA care (sample); (2) clearly defined EBIs (phenomenon of interest); (3) comprehensive descriptions of EBI adaptation from their original context (design); (4) specific adaptation frameworks or methods identified (evaluation); and (5) quantitative or qualitative methods used (research type). These criteria helped us identify papers where care specific to veterans was being adapted, there was a clear description of the EBI being implemented, and specifics on the adaptation process were included.

Data were abstracted by one reviewer (AKD). Initially, study titles and abstracts with our key terms were evaluated for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Study titles and abstracts that met all SPIDER criteria were selected for full-text review. For samples that also included VA providers and/or staff, we retained the article as long as veteran outcomes were described or veterans were part of the feedback process for articles with qualitative findings. Searches were limited to the English language; articles were additionally excluded if they consisted of non-original research (e.g., review article, meta-analysis, opinion, letter, case report, case series, or commentary) or research that was not peer-reviewed.

Published protocols for studies and completed studies were included. For papers where we retrieved both a protocol and completed study, only the paper on the completed study was retained. Data was extracted by SPIDER criteria into a REDCap database.22 Following abstraction, we charted and summarized our results.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Data was summarized by the veteran population studied, the modification content area (e.g., mental health, diabetes), outcomes measured, and key findings. We include brief details on demographics for the samples in each article if they were provided. We synthesized our data based on process-specific components from the expanded Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications (FRAME)2 and using the FRAME Excel Tracking Spreadsheet (available at https://med.stanford.edu/fastlab/research/adaptation.html) to chart our results. As we were specifically interested in what and when EBIs were adapted as well as who was involved in the study, these were the FRAME elements we focused on for this analysis. We used elements of FRAME including when the modification occurred (e.g., pre-implementation, implementation, scale-up), whether the adaptations were planned, who participated in the decision to modify, and what was modified (e.g., content, trainings, implementation activities).

FINDINGS

Description of Studies

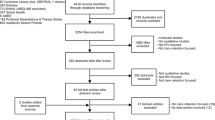

Figure 1 describes our article identification process. We retrieved 922 abstracts based on our search terms. After removing duplicates (n = 277), we were left with 645 titles and abstracts for review. Following the review of these 645 titles and abstracts, we excluded 236 of the 645 (37%) articles as they did not describe an adaptation, 205 of the 645 (32%) studies as they were reviews or case studies, and 156 of the 645 articles (24%) that did not include a veteran sample. This left 48 of the 645 (7%) articles for full-text review. Ten articles (21% out of the 48 eligible) met the SPIDER criteria. Most excluded articles (n = 28/38; 74%) did not include a comprehensive description of how the EBI was adapted from its original context. Other reasons for exclusion included the sample was not comprised of veterans or there were no veteran outcomes reported (n = 6/38, 16%) or the article was a review study or protocol for a completed study that was included (n = 4/38, 11%). A review of reference lists of eligible articles resulted in the identification of one additional article, resulting in a total of 11 articles included in this review. Ten of the included articles described results from complete studies23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32; one article33 was a protocol describing a study that was ongoing at the time of article retrieval.

Description of Adaptations

Included articles described adaptation of EBIs for mental health (n = 4),23,30,32,33 access to care and/or care delivery (n = 3),26,29,30 diabetes prevention (n = 2),24,27 substance use (n = 2),25,31 weight management (n = 1),32 care specific to cancer survivors (n = 1),28 and/or to reduce criminal recidivism among veterans (n = 1)33. All papers used some form of qualitative feedback to inform adaptations. Qualitative interviews took place with veterans in eight papers (73%)23,25,26,27,28,29,32,33 and providers and/or VA leadership (e.g., clinical practice leadership, facility administrators, VISN directors) in five papers (45%).23,24,25,29,30 Six articles (55%) provided information on participant demographics.24,25,27,28,31,32 Two articles included samples of all27 or predominantly female veterans24; five of the six articles included samples with over 50% White veterans (Table 1).24,25,28,31,32

A description of the adaptations made to each EBI, and the potential impacts of these adaptations to the original EBI, is included in Table 2. Additionally, Table 2 shows that four (36%) of the included articles adapted EBIs for veterans or VA providers that were developed externally from the VA.23,25,28,33 Four other papers (36%) adapted EBIs already in use at the VA but tailored those interventions for specific veteran populations, including rural veterans,26,29 women veterans,27 or veterans with PTSD.32 Three (27%) articles described the use of evidence-based quality improvement (EBQI) methods to test the delivery of an intervention by clinical staff instead of researchers.24,30,31

Frameworks used to guide the adaptation process included EBQI processes (n = 2),30,31 Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM; n = 2),28,33 and Practical Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM; n = 1).29 Other frameworks included the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, Evaluation (ADDIE) model,23 Promoting Action on Research in Health Services (PARIHS),24 and Method for Program Adaptation through Community Engagement (M-PACE).25 Two studies used formative evaluation to provide information about implementation.26,27 Finally, one study used the VA Peer Support Implementation Toolkit,32 VA-designed guidelines outlining how to train peer support specialists.34

Outcomes

Most articles reported outcomes that were qualitative in nature such as uptake,26 usability,25 reach,28 satisfaction,32 and barriers/facilitators of engagement with the adapted EBIs.23,24,25,27 Other key findings showed that modifications to existing EBIs better reflected specific experiences of veterans.23,25 Two studies with quantitative findings found that adaptations to EBIs resulted in meaningful weight loss32 and reduced depression symptoms as measured by PHQ-9 scores.30 Two articles reported null findings in their main outcomes,28,31 although both of these studies indicated positive findings on secondary outcomes (Table 3).

FRAME Components

There was a diverse range of modifications across our eleven articles based on the FRAME elements we examined. While the majority of studies (55%) were modified in the pre-implementation, planning, or pilot phases,23,25,28,29,30,33 there were examples of studies modified in the scale-up (27%)24,26,31 and maintenance and/or sustainment (18%)27,32 phases. All articles wrote about planned proactive adaptations to EBIs. Most adaptations (91%) involved the participation of the research team23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,32,33, providers (73%)24,25,26,29,30,31,32,33, and/or veterans (73%)25,26,27,28,29,30,32,33 in the modification process. Three articles detailed leadership participation in the adaptation process.24,30,31 “Participation” included the involvement of stakeholders in providing feedback on the feasibility and acceptability of a given EBI and the use of formative and participatory research methods involving veterans who would directly benefit from a particular EBI. Modifications were most often contextual,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,32,33 with fewer studies detailing content,23,28,30,31,32,33 training and evaluation,24,30,31 or implementation activity modifications.24,26,27,31 Of the studies that made contextual modifications, these modifications were most often in the setting23,24,25,26,28,29,30 or population25,27,28,29,30,32,33, with fewer studies examining contextual modifications to the format27,32 or personnel24,30 involved in the intervention (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Articles identified in this scoping review of adaptation for veterans receiving VA care used a variety of methods and frameworks to guide EBI adaptations. The majority of articles reported on modifications made to EBIs in the pilot phase, resulting in articles with smaller (pilot) sample sizes, and most reported qualitative findings such as feedback from veterans. Despite the small number of articles that shared quantitative findings, articles indicated veteran satisfaction, increased veteran focus, and clinically meaningful results with the given adaptations. For example, in Hoerster et al.’s 32 study, the MOVE + UP intervention for weight loss in veterans with PTSD found a meaningful loss of weight, high participant satisfaction, and PTSD symptom improvements in the cohort of veterans who completed the intervention. Not surprisingly, most modifications to contextual components of an EBI were made to the setting or population. This was evident in Dyer et al.’s 27 study where the Diabetes Prevention Program was tailored for gender (e.g., women veterans) and preferred modality of intervention delivery (e.g., online vs. in-person). This finding likely reflects the modification being conducted within the VA or with a greater emphasis on the unique characteristics of veterans. This is particularly illustrated by Blonigen et al. 25, where veterans provided feedback on the Step Away mobile app and in particular suggested that “modifying the appearance and design of the app to include more veteran-centric content” would benefit its use in a veteran population (e.g., adding links to veteran support groups and including veteran-specific statistics on problem drinking).

The papers reviewed here provide many examples of adaptations for veterans receiving care within the VA. All articles used some combination of common adaptation steps as identified in previous work,35 most often including consulting with stakeholders, adapting the original EBI, training staff, and testing the adapted materials. Most studies included here tested adapted EBIs in a relatively small pilot sample of veterans. This is likely due to the recent effort to adapt EBIs in a veteran population, highlighted by the majority (73%) of our included studies being published during or after 2018, and suggests that larger implementation studies may be forthcoming. However, the work presented here provides insight into achieving successful adaptation within the VA system.

While defining success in implementation work can be subjective,36 this scoping review provides examples of studies that describe implementation outcomes as outlined by Proctor et al.,37 such as acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, and feasibility, that are associated with improved outcomes, patient care, and user satisfaction. There is considerable opportunity to expand the use of EBI adaptations to meet the specific needs of veteran populations. Tailoring to subgroups that were not observed in our review (e.g., LGBTQ + , racial/ethnic minority subgroups) may be valuable, especially given the changing demographics of veterans and VA users. In the articles that provided sample demographics, most examined adaptations in White, male veterans. However, VA population projections show that both women and minority veterans are increasing,38,39 suggesting that there is a need to examine EBI modifications among growing veteran subgroups. Indeed, these findings demonstrate that future adaptation efforts could include greater input from samples of diverse veteran stakeholders.

We acknowledge that this review has limitations. First, while we conducted a broad review of available literature, consistent with rigorous scoping review methodology,18,19,40 there is always potential for missed articles. Second, scoping reviews by design do not examine the quality of the evidence examined. Third, we only included descriptions of adaptations as available in the included articles; it is likely that many other modifications are continuing to occur in routine clinical care that have not yet been systematically detected.41 Finally, we were unable to account for publication bias, and like any review, it remains unknown how much is published (or unpublished) about tailoring EBIs for veterans that does not result in the intended outcomes. Interestingly, all reviewed articles proactively planned their adaptations to EBIs. This is likely due to the nature of the modifications being made for a specific population (i.e., veterans).

In this first examination of adaptations to EBIs within the VA, we found several articles detailing methods and frameworks of such adaptations. Future steps include examining fidelity to the original interventions under study, which may first require a revised search to determine whether any of the EBIs that were studied in pre-implementation or pilot research have been implemented in larger-scale trials. Our results show that the VA is supportive of adaptations within the healthcare system, evidenced by the involvement of veterans, providers, and leadership across many of the reviewed articles. Continuing to expand the use of EBI adaptations to meet the specific needs of veteran populations may improve healthcare delivery and veteran satisfaction with that care.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Haardoerfer R, et al. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implement Sci 2018;13(1):125. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0815-9.

Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci 2019;14(1):58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y.

Barrera M, Jr., Berkel C, Castro FG. Directions for the Advancement of Culturally Adapted Preventive Interventions: Local Adaptations, Engagement, and Sustainability. Prev Sci 2017;18(6):640-648. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0705-9.

Cabassa LJ, Druss B, Wang Y, Lewis-Fernandez R. Collaborative planning approach to inform the implementation of a healthcare manager intervention for Hispanics with serious mental illness: a study protocol. Implement Sci 2011;6:80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-80.

Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, Gottlieb NH. Intervention Mapping: Designing theory and evidencebased health promotion programs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2006.

Barrera M, Jr., Castro FG. A Heuristic Framework for the Cultural Adaptation of Interventions. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract 2006;13(4):311-316. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00043.x.

Kumpfer KL, Pinyuchon M, Teixeira de Melo A, Whiteside HO. Cultural adaptation process for international dissemination of the strengthening families program. Eval Health Prof 2008;31(2):226-39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278708315926.

Stirman SW, Gamarra J, Bartlett B, Calloway A, Gutner C. Empirical Examinations of Modifications and Adaptations to Evidence-Based Psychotherapies: Methodologies, Impact, and Future Directions. Clin Psychol (New York) 2017;24(4):396-420. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12218.

Rogers EM. Diffusions of Innovations. 4th ed. New York: Free Press, 1995.

Cabassa LJ. Implementation Science: Why it matters for the future of social work. J Soc Work Educ 2016;52(Suppl 1):S38-S50. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28216992). Accessed 28 June 2022.

Chambers DA, Norton WE. The Adaptome: Advancing the Science of Intervention Adaptation. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(4 Suppl 2):S124-31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.05.011.

Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Statistics at a Glance, Veteran Population Projection Model (VetPop) 2018. Veterans Benefits Administration, Veterans Health Administration, Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. 6/30/21 https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Quickfacts/Stats_at_a_glance_6_30_21.PDF. Accessed 31 August 2022.

Hayes P. Diversity, equity, inclusion – VA goals. 7/22/21 https://blogs.va.gov/VAntage/92022/diversity-equity-inclusion-va-goals/#:~:text=Today%2C%20about%2027%25%20of%20Veterans%20are%20members%20of,belonged%20to%20a%20racial%20or%20ethnic%20minority%20group. Accessed 28 June 2022.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Veterans Employment Toolkit. 7/7/21 https://www.va.gov/VETSINWORKPLACE/mil_culture.asp. Accessed 28 June 2022.

Falca-Dodson M. Why Military Culture Matters: The Military Member’s Experience. Presented by the Department of Veterans Affairs War Related Illness and Injury Study Center (WRIISC). https://www.warrelatedillness.va.gov/education/conferences/2010-sept/slides/2010_09_15_Falca-DodsonM-Why-Military-Culture-Matters.ppt. Accessed 28 June 2022.

Cotner BA, Ottomanelli L, Keleher V, Dirk L. Scoping review of resources for integrating evidence-based supported employment into spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41(14):1719-1726. (In eng). doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1443161.

Olenick M, Flowers M, Diaz VJ. US veterans and their unique issues: enhancing health care professional awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract 2015;6:635-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.2147/AMEP.S89479.

Anderson S, Allen P, Peckham S, Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Res Policy Syst 2008;6:7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-6-7.

Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence. In: Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N, eds. Studying the Organization and Delivery of Health Services: Research Methods. London: Routledge; 2001:188-220.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res 2012;22(10):1435-43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938.

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:579. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377-81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010.

Abraham TH, Marchant-Miros K, McCarther MB, et al. Adapting Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management for Veterans Affairs Community-Based Outpatient Clinics: Iterative Approach. JMIR Ment Health 2018;5(3):e10277. doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/10277.

Arney J, Thurman K, Jones L, et al. Qualitative findings on building a partnered approach to implementation of a group-based diabetes intervention in VA primary care. BMJ Open 2018;8(1):e018093. (In eng). doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018093.

Blonigen D, Harris-Olenak B, Kuhn E, Humphreys K, Timko C, Dulin P. From "Step Away" to "Stand Down": Tailoring a Smartphone App for Self-Management of Hazardous Drinking for Veterans. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020;8(2):e16062. (In eng). doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/16062.

Day SC, Day G, Keller M, et al. Personalized implementation of video telehealth for rural veterans (PIVOT-R). Mhealth 2021;7:24. (In eng). doi: https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2020.03.02.

Dyer KE, Moreau Jl, Finley E, et al. Tailoring an evidence-based lifestyle intervention to meet the needs of women Veterans with prediabetes. Women Health 2020;60(7):748-762. (In eng). doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2019.1710892.

King K, Gosian J, Doherty K, et al. Implementing yoga therapy adapted for older veterans who are cancer survivors. Int J Yoga Therap 2014;24:87-96. (In eng).

Leonard C, Gilmartin H, McCreight M, et al. Operationalizing an Implementation Framework to Disseminate a Care Coordination Program for Rural Veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(Suppl 1):58-66. (In eng). doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04964-1.

Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health 2010;28(2):91-113. (In eng). doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020302.

Yano EM, Rubenstein LV, Farmer MM, et al. Targeting primary care referrals to smoking cessation clinics does not improve quit rates: implementing evidence-based interventions into practice. Health Serv Res 2008;43(5 Pt 1):1637-61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00865.x.

Hoerster KD, Tanksley L, Simpson T, et al. Development of a Tailored Behavioral Weight Loss Program for Veterans With PTSD (MOVE!+UP): A Mixed-Methods Uncontrolled Iterative Pilot Study. Am J Health Promot 2020;34(6):587-598. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117120908505.

Blonigen DM, Cucciare MA, Timko C, et al. Study protocol: a hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial of Moral Reconation Therapy in the US Veterans Health Administration. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):164. (In eng). doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-2967-3.

Chinman M, Henze K, Sweeney P. Peer specialist toolkit: implementing peer support services in VHA. http://www.mirecc.va.gov/visn4/docs/Peer_Specialist_Toolkit_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 3 November 2022.

Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Udelson H, et al. A scoping study of frameworks for adapting public health evidence-based interventions. Transl Behav Med 2019;9(1):1-10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibx067.

Shepherd HL, Geerligs L, Butow P, et al. The Elusive Search for Success: Defining and Measuring Implementation Outcomes in a Real-World Hospital Trial. Front Public Health 2019;7:293. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00293.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2011;38(2):65-76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Frayne S, Phibbs CS, Saechao FS, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 4: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics, Utilization, Health Profile, and Geographic Distribution. Washington DC: February 2018 2018. https://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/WHS_Sourcebook_Vol-IV_508c.pdf. Accessed 10 October 2022.

National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Veteran Population Projections 2020–2040; Source: VA Veteran Population Projection Model 2018. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/Demographics/New_Vetpop_Model/Vetpop_Infographic2020.pdf. Accessed 31 August 2022.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8(1):19-32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Wiltsey Stirman S, La Bash H, Nelson D, Orazem R, Klein A, Sayer NA. Assessment of modifications to evidence-based psychotherapies using administrative and chart note data from the US department of veterans affairs health care system. Front Public Health 2022;10:984505. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.984505.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. The authors would like to acknowledge support from the Institute for Implementation Science Scholars (IS-2), which is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) and Office of Disease Prevention, administered by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders, R25DK123008. Drs. Cabassa and Hamilton are mentors in the IS-2 program; Dr. Kroll-Desrosiers is a former scholar. Dr. Hamilton was supported by a VA Health Services Research & Development Research Career Scientist Award (RCS 21-135). Drs. Hamilton and Finley are additionally supported by EMPOWER QUERI 2.0 (QUE 20-028); Dr. Kroll-Desrosiers is a mentee in the EMPOWER QUERI 2.0 mentoring core.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kroll-Desrosiers, A., Finley, E.P., Hamilton, A.B. et al. Evidence-Based Intervention Adaptations Within the Veterans Health Administration: a Scoping Review. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 2383–2395 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08218-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08218-z