Abstract

Background

For patients undergoing resection of colorectal liver metastases (CLMs), the prognostic role of somatic gene alterations is increasingly recognized. F-box/WD repeat–containing protein 7 (FBXW7) is a tumor suppressor gene found in approximately 10% of patients with colorectal cancer. The aim of this study is to assess the association of FBXW7 with overall survival after CLM resection.

Methods

Patients who underwent initial CLM resection during 2001–2016 and had genetic sequencing data were studied. Risk factors for overall survival (OS) were evaluated with Cox proportional hazards models using backward elimination.

Results

Of 2045 patients who underwent CLM resection during the study period, 476 were included. The majority (90.5%) underwent prehepatectomy chemotherapy. A total of 27 patients (5.7%) had FBXW7 alteration, along with 240 (50.4%) RAS, 337 (70.8%) TP53, 51 (10.7%) SMAD4, and 27 (5.7%) BRAF. Cox proportional hazards model analyses including 5 somatic gene alteration status and 12 clinicopathologic factors revealed FBXW7(hazard ratio [HR] 1.99, P = 0.015), BRAF (HR 2.47, P = 0.023), RAS (HR 2.42, P < 0.001), TP53 (HR 2.00, P < 0.001), and SMAD4 alterations (HR 1.90, P = 0.004) as significantly associated with OS, together with three clinicopathologic factors, prehepatectomy chemotherapy > 6 cycles (HR 1.51, P = 0.021), number of CLM (HR 1.05, P = 0.007), and largest liver metastasis diameter (HR 1.07, P = 0.023). The covariate-adjusted 5-year OS was significantly lower in patients with FBXW7 alteration than in patients with FBXW7 wild-type (40.4% vs.59.4%, P = 0.015).

Conclusions

FBXW7 alterations are associated with worse survival after CLM resection. The information on multiple somatic gene alterations is imperative for risk stratification and patient selection for CLM resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Liver resection remains the only curative treatment option for patients with colorectal liver metastases (CLMs). Clinicopathologic factors, such as number and diameter of CLM, concomitant extrahepatic metastases, carcinoembryonic antigen level, and surgical margins, are known to be associated with survival following CLM resection.1,2 Evidence suggests that somatic gene alterations in RAS, TP53, and SMAD4 are associated with survival following CLM resection and provide additional data that augments decision on treatment sequencing and patient selection.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 However, the impact of rare alterations on oncologic outcomes has been recently described, such as those in BRAF, and thus their detection is critical for surgical decision-making and informed discussion on prognosis for patients with CLM.13,14

F-box/WD repeat–containing protein 7 (FBXW7) is a tumor suppressor gene implicated in the degradation of mediators of cell cycle progression. A previous study with extensive genetic analysis showed that FBXW7 was altered in various human tumor types, with an overall alteration frequency of approximately 6%.15 Of these, FBXW7 alteration was found in 35% of cholangiocarcinoma, 31% of T cell acute lymphocytic leukemia, 10% of colorectal cancer, and 9% of endometrial cancer.15 For patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, overall survival (OS) was significantly worse in patients with FBXW7 alteration than in patients with FBXW7 wild-type.16 However, for patients who undergo resection of CLM, the prognostic role of FBXW7 has not been reported. We hypothesized that FBXW7 alterations would negatively impact survival for patients with resected CLM. Within this context, the primary aim was to evaluate the survival impact of FBXW7 alteration for patients undergoing CLM resection.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We identified patients who underwent initial CLM resection in the Department of Surgical Oncology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center from 2001 to 2016, from a prospectively maintained database. Patients who had genetic sequencing data more than 46 genes were included. Demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics, and survival outcomes, were collected. This study was approved by the institutional review board.

Surgical Management of CLM

As previously described,9 our group performs preoperative chemotherapy followed by liver resection and postoperative chemotherapy in most patients with CLM. Preoperative chemotherapy generally consists of oxaliplatin- or irinotecan-containing regimens plus bevacizumab and is administered for 4 cycles. Postoperatively, 8 cycles of the same regimens without bevacizumab are administered.17 CLMs are deemed resectable if negative surgical margins can be achieved while preserving an adequate standardized future liver remnant volume18 If the future liver remnant is insufficient, preoperative portal vein embolization and two-stage hepatectomy are used. 19 Patients are followed after CLM resection with axial imaging every 3–4 months for the first 2 years and every 4–6 months for the subsequent 3 years.20

Somatic Gene Alteration Profiling

As previously described,21 tumor DNA was isolated from 5-mm-thick unstained sections on the basis of tumor tissue blocks or slides from primary colorectal cancer or CLM specimens. Macrodissection was performed in cases of low tumor cellularity. Next-generation sequencing was performed with an AmpliSeq gene panel related to cancer (Supplementary Table 1) using the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (Life Technologies, CA) in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment–certified molecular diagnostic laboratory.22

Definitions

We defined synchronous metastases as metastases diagnosed within 12 months of primary tumor diagnosis and a positive surgical margin as the presence of tumor cells within 1 mm of the transection line. Primary tumors were staged according to the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, eighth edition.23

Statistical Analysis

KRAS and NRAS alterations were grouped in a single category, RAS alteration, and analyzed as previously described24,25 and are supported by the fact that survival after CLM resection was worse in patients who had metastatic colorectal cancer and NRAS alteration.26,27,28

Categorical variables were expressed in numbers and percentages and were compared among groups using Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were expressed as median values with the interquartile range. A Cox proportional hazards model analysis was performed with clinicopathologic factors, somatic genes which were associated with prognosis (BRAF, RAS, TP53, and SMAD4),29 and FBXW7. A Cox proportional hazards model analysis initially included age (continuous variable), sex, primary tumor location, T category, primary lymph node metastasis, prehepatectomy carcinoembryonic antigen level (continuous variable), timing of metastasis (synchronous vs. metachronous), prehepatectomy chemotherapy, extrahepatic disease, number of CLM (continuous variable), largest liver metastasis diameter (continuous variable), surgical margin status (R1 vs. R0), BRAF alteration, RAS alteration, TP53 alteration, SMAD4 alteration, and FBXW7 alteration. A backward elimination with a threshold P value of 0.05 was used to select variables for the final models. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each factor. We estimated the 5-year OS time and survival curves adjusted for covariates by using direct adjusted survival estimation.30,31 This method uses the Cox regression model to estimate survival probabilities at each time point for each individual and averages them to obtain an OS estimate. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by using Schoenfeld residuals. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analysis was conducted with SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Study Population

Of 2045 patients who underwent CLM resection during the study period, 476 met inclusion criteria (Supplementary Figure 1). Because genetic sequencing was not frequently performed before 2010, 407 (85.5%) of the 476 patients underwent CLM resection from 2011 to 2016.

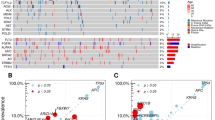

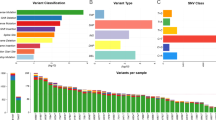

Table 1 shows demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics. A total of 431 patients (90.5%) underwent prehepatectomy chemotherapy. Of these, 338 (71.0%) received anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agent-containing regimen, and 37 (7.7%) received anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) containing regimen. BRAF, RAS, TP53, SMAD4, and FBXW7 were altered in 11 patients (2.3%), 240 patients (50.4%), 337 patients (70.8%), 51 patients (10.7%), and 27 patients (5.7%), respectively. Of the 27 patients with FBXW7 alteration, 26 (96.3%) had mutation of FBXW7 including 25 single nucleotide variation and 1 duplication, and 1 patient missed the detailed information. No amplification was found in patients with FBXW7 alteration (Fig. 1a). Co-alteration of FBXW7 and other somatic genes are shown in Fig. 1b. The frequency of RAS alteration was significantly higher in patients with FBXW7 alteration than in patients with FBXW7 wild-type (77.8% vs. 44.8%, P = 0.005). The frequencies of BRAF, TP53, and SMAD4 were similar between patients with and without FBXW7 alteration.

The median duration of follow-up was 3.1 years (interquartile range, 2.1–4.8 years). During the follow-up period, 170 (35.7%) patients died and 388 (81.5%) patients experienced recurrence, including 24 patients with FBXW7 alteration and 364 patients with FBXW7 wild-type. Recurrence rates in the liver alone, lung alone, and two or more sites were 20.8%, 33.3%, and 29.2% in patients with FBXW7 alteration as compared to 36.5%, 28.9%, and 21.4% in patients with FBXW7 wild-type.

A Cox Proportional Hazards Model Analysis for OS After CLM Resection

We evaluated FBXW7 alteration status in a Cox proportional hazards model analysis, together with reported prognostic somatic gene (BRAF, RAS, TP53, and SMAD4) in this patient group and clinicopathologic factors. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model analysis revealed that alterations of FBXW7 was an independent predictor of OS together with BRAF, RAS, TP53, and SMAD4 (Table 2). Additionally, prehepatectomy chemotherapy > 6 cycles, number of CLM, and largest liver metastasis diameter were associated with OS (Table 2).

OS Estimates Stratified by Alteration Status of FBXW7

OS curves with and without adjustment for other prognostic factors are shown in Fig. 2. The 5-year OS was significantly lower in patients with FBXW7 alteration than in patients with FBXW7 wild-type: 29.7% vs. 61.2%, P = 0.005. After adjustment for other prognostic factors, the covariate-adjusted 5-year OS remains significantly lower in patients with FBXW7 alteration than in patients with FBXW7 wild-type: 40.4% vs. 59.4%, P = 0.015.

Overall survival (OS) by FBXW7 alteration status. a OS curves. b OS curves after adjustment for somatic gene alteration status (BRAF, RAS, TP53, and SMAD4), prehepatectomy chemotherapy (> 6 cycles vs. ≤ 6 cycles or no prehepatectomy chemotherapy), number of CLM, and largest liver metastasis diameter

OS Estimates Stratified by Alteration Status of RAS and FBXW7

Because the frequency of FBXW7 alteration was significantly higher in patients with RAS alteration than in patients with RAS wild-type, we evaluated OS stratified by RAS and FBXW7 alteration (Fig. 3). The 5-year OS was lower in patients with co-alteration of RAS and FBXW7 alteration than in patients with RAS alteration and FBXW7 wild-type (27.1% vs. 53.4%, P = 0.066) and in patients with RAS wild-type (27.1% vs. 67.0%, P < 0.001). After adjustment for other prognostic factors, the covariate-adjusted 5-year OS was significantly lower in patients with co-alteration of RAS and FBXW7 alteration than in patients with RAS alteration and FBXW7 wild-type (26.1% vs. 47.0%, P = 0.036) and in patients with RAS wild-type (26.1% vs. 70.6%, P < 0.001). We repeated the analysis of OS stratified by TP53 and FBXW7 alteration. Similarly, the 5-year OS with and without adjustment for other prognostic factors was lower in patients with co-alteration of TP53 and FBXW7 alteration (Supplementary Figure 2). The 5-year OS without adjustment of patients with alterations in FBXW7, RAS, and TP53 (triple alteration, 17.9%) was worse than alterations in FBXW7 and RAS or FBXW7 and TP53 or RAS and TP53 (double alteration, 38.2%) although the number of patients with alteration in FBXW7, RAS, and TP53 was small (n = 12).

Overall survival (OS) by RAS and FBXW7 alteration status. a OS curves. b OS curves after adjustment for somatic gene alteration status (BRAF, TP53, and SMAD4), prehepatectomy chemotherapy (> 6 cycles vs. ≤ 6 cycles or no prehepatectomy chemotherapy), number of CLM, and largest liver metastasis diameter

Discussion

Patients with FBXW7 alteration experienced worse OS after CLM resection compared to FBXW7 wild-type patients. When grouped by RAS and FBXW7, or TP53 and FBXW7 alteration status, the stratification of prognosis was more refined. Of the 12 clinicopathologic factors, only 3 factors (prehepatectomy chemotherapy > 6 cycles, number of CLM, and largest liver metastasis diameter) were associated with OS when assessed with somatic gene alteration status of FBXW7, BRAF, RAS, TP53, and SMAD4. Our findings confirm the prognostic importance of knowing the status of multiple potential somatic gene alterations in CLM patients due to the genomic heterogeneity of colorectal cancer.

FBXW7 is a tumor suppressor gene associated with the Notch signaling pathway (Fig. 4).32 Our study showed that the frequency of FBXW7 alteration was 5.7% in patients with CLM, in line with previous studies that reported frequency rates of 6–10%.15,33 Importantly, this alteration was more frequent among CLM patients than BRAF alteration, which is well recognized to be a poor prognostic marker: the percentage of patients with BRAF alteration was 2.3% in our study and 2–5% in a large series including patients with CLM.29 In line with previous reports,15,34 our study found that the frequency of FBXW7 alteration was significantly higher in patients with RAS alteration than in patients who were RAS wild-type. The Notch pathway is a regulator of cell growth and differentiation.35 Inactivation of FBXW7 causes abnormal accumulation of the intracellular domain of Notch1 and influences cell growth.36 As such, alteration of FBXW7 may result in uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation and thus, a deleterious effect on survival through the Notch pathway. The resultant negative survival impact has been reported for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.16 Nonetheless, our study is the first to show that OS after CLM resection was significantly worse in patients with FBXW7 alteration than in patients with FBXW7 wild-type.

The Cancer Genome Atlas project has detailed the landscape of somatic gene alteration of colorectal cancer in the context of cancer-related signaling pathways.37 Our group reported that alteration of RAS, TP53, and SMAD4 and co-alteration of RAS and TP53 were associated with worse survival.4,8,9,10,21RAS, TP53, and SMAD4 belong to three cancer-related signaling pathways: the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, the p53 pathway, and the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway, respectively.37 Because these three pathways are associated with tumor-cell growth, it may be plausible that the malfunction of these pathways influences prognosis in patients with CLM. The information on alterations in these pathways may have high impact on clinical practice because the alterations of RAS and TP53 were found in more than 50% of this patient group.

Alterations of FBXW7 and BRAF are less frequent than alterations of RAS, TP53, and SMAD4. However, we believe that it is important to identify rare deleterious alterations in order to more succinctly predict CLM patients’ prognosis. It is being increasingly recognized that the interplay of multiple altered signaling pathways in CLM may cause deleterious effect and result in observable differences in tumor phenotype, response to therapy, and pattern of recurrence after resection. Therefore, it is imperative that we identify the status of the rare alterations, such as that of BRAF and FBXW7, because they not only allow for prognostication on their own, but when preset in combination with others provide more accurate data for patients with CLM. This is clearly demonstrated in our previous reports8,21 and here with the survival differences in RAS alteration patients with or without a co-alteration in FBXW7. The data presented emphasizes the importance of multiple gene testing as single gene alterations are insufficient for accurate prognostication after CLM resection. Whether these somatic alterations can definitively direct patient selection for surgery and treatment sequencing is an evolving subject. We may use this information to identify patients who have CLM with favorable molecular biology (i.e., wild-type in FBXW7, BRAF, RAS, TP53, and SMAD4) and may be best suited for aggressive surgery and local therapies. For example, patients with poor clinicopathologic factors (e.g., number of CLMs > 10, largest diameter of CLM > 10 cm, multiple primary lymph node metastases, extrahepatic metastases) but with favorable molecular biology may expect oncological benefits using aggressive treatment strategies.

Our study should be understood in the context of limitations. First, the retrospective single-institution design makes it difficult to preclude all biases. Nonetheless, the large size of the study cohort with complete data regarding the status of 46 somatic gene alterations allowed the analysis of patients with FBXW7 alteration. Second, we analyzed patients who had complete data of 5 somatic genes (FBXW7, BRAF, RAS, TP53, and SMAD4). As such, we included only patients who underwent the 46-gene panel test in the study. Third, we did not analyze specific types of genetic alteration because the majority of FBXW7 alterations were single nucleotide variations followed by duplication. Last, we studied patients who underwent CLM resection for a relatively long period from 2001 to 2016. However, this may be a limited impact because genetic sequencing has only been performed with regularity in the past several years, and 85.5% of the patients in the study underwent CLM resection after 2011 and had similar management of CLM. Further study including more patients may elucidate the interaction of multiple alterations in FBXW7 and other somatic genes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, FBXW7 alteration was found in 5.7% of patients undergoing CLM resection and was associated with worse survival. This finding further supports the genetic heterogeneity of colorectal cancer and the importance of determining the status of multiple somatic gene alterations for risk stratification for patients with CLM considering resection.

Abbreviations

- CLM:

-

colorectal liver metastases

- FBXW7 :

-

F-box/WD repeat–containing protein 7

- OS:

-

overall survival

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- CI:

-

confidence intervals

- VEGF:

-

vascular endothelial growth factor

- EGFR:

-

epidermal growth factor receptor

- MAPK:

-

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- TGF-β:

-

transforming growth factor-β

References

Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Annals of surgery. 1999;230(3):309–18; discussion 18–21.

Rees M, Tekkis PP, Welsh FK, O’Rourke T, John TG. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Annals of surgery. 2008;247(1):125-35. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815aa2c2.

Nash GM, Gimbel M, Shia J, Nathanson DR, Ndubuisi MI, Zeng ZS et al. KRAS mutation correlates with accelerated metastatic progression in patients with colorectal liver metastases. Annals of surgical oncology. 2010;17(2):572-8. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0605-3.

Vauthey JN, Zimmitti G, Kopetz SE, Shindoh J, Chen SS, Andreou A et al. RAS mutation status predicts survival and patterns of recurrence in patients undergoing hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases. Annals of surgery. 2013;258(4):619–26; discussion 26–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a5025a.

Brudvik KW, Kopetz SE, Li L, Conrad C, Aloia TA, Vauthey JN. Meta-analysis of KRAS mutations and survival after resection of colorectal liver metastases. The British journal of surgery. 2015;102(10):1175-83. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9870.

Amikura K, Akagi K, Ogura T, Takahashi A, Sakamoto H. The RAS mutation status predicts survival in patients undergoing hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases: The results from a genetic analysis of all-RAS. Journal of surgical oncology. 2018;117(4):745-55. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.24910.

Wang K, Liu W, Yan XL, Li J, Xing BC. Long-term postoperative survival prediction in patients with colorectal liver metastasis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(45):79927-34. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.20322.

Chun YS, Passot G, Yamashita S, Nusrat M, Katsonis P, Loree JM et al. Deleterious Effect of RAS and Evolutionary High-risk TP53 Double Mutation in Colorectal Liver Metastases. Annals of surgery. 2019;269(5):917-23. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002450.

Kawaguchi Y, Lillemoe HA, Panettieri E, Chun YS, Tzeng CD, Aloia TA et al. Conditional Recurrence-Free Survival after Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases: Persistent Deleterious Association with RAS and TP53 Co-Mutation. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2019;229(3):286-94 e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2019.04.027.

Mizuno T, Cloyd JM, Vicente D, Omichi K, Chun YS, Kopetz SE et al. SMAD4 gene mutation predicts poor prognosis in patients undergoing resection for colorectal liver metastases. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2018;44(5):684-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.02.247.

Lang H, Baumgart J, Heinrich S, Tripke V, Passalaqua M, Maderer A et al. Extended Molecular Profiling Improves Stratification and Prediction of Survival After Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Annals of surgery. 2019;270(5):799-805. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003527.

Datta J, Smith JJ, Chatila WK, McAuliffe JC, Kandoth C, Vakiani E et al. Co-Altered Ras/B-raf and TP53 is Associated with Extremes of Survivorship and Distinct Patterns of Metastasis in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2390.

Gagniere J, Dupre A, Gholami SS, Pezet D, Boerner T, Gonen M et al. Is Hepatectomy Justified for BRAF Mutant Colorectal Liver Metastases?: A Multi-institutional Analysis of 1497 Patients. Annals of surgery. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002968.

Margonis GA, Buettner S, Andreatos N, Kim Y, Wagner D, Sasaki K et al. Association of BRAF Mutations With Survival and Recurrence in Surgically Treated Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Liver Cancer. JAMA surgery. 2018;153(7):e180996. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2018.0996.

Malapelle U, Pisapia P, Sgariglia R, Vigliar E, Biglietto M, Carlomagno C et al. Less frequently mutated genes in colorectal cancer: evidences from next-generation sequencing of 653 routine cases. Journal of clinical pathology. 2016;69(9):767-71. https://doi.org/10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203403.

Korphaisarn K, Morris VK, Overman MJ, Fogelman DR, Kee BK, Raghav KPS et al. FBXW7 missense mutation: a novel negative prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8(24):39268-79. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16848.

Brouquet A, Abdalla EK, Kopetz S, Garrett CR, Overman MJ, Eng C et al. High survival rate after two-stage resection of advanced colorectal liver metastases: response-based selection and complete resection define outcome. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(8):1083-90. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6132.

Vauthey JN, Chaoui A, Do KA, Bilimoria MM, Fenstermacher MJ, Charnsangavej C et al. Standardized measurement of the future liver remnant prior to extended liver resection: methodology and clinical associations. Surgery. 2000;127(5):512-9. https://doi.org/10.1067/msy.2000.105294.

Kawaguchi Y, Lillemoe HA, Vauthey JN. Dealing with an insufficient future liver remnant: Portal vein embolization and two-stage hepatectomy. Journal of surgical oncology. 2019;119(5):594-603. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.25430.

Kawaguchi Y, Kopetz S, Lillemoe HA, Hwang H, Wang X, Tzeng CD, Chun YS, Aloia TA, Vauthey JN. A new surveillance algorithm after resection of colorectal liver metastases based on changes in recurrence risk and ras mutation status. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(11):1500-1508. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2020.7596.

Kawaguchi Y, Kopetz S, Newhook TE, De Bellis M, Chun YS, Tzeng CD et al. Mutation Status of RAS, TP53, and SMAD4 is Superior to Mutation Status of RAS Alone for Predicting Prognosis after Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2019;25(19):5843-51. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0863.

Singh RR, Patel KP, Routbort MJ, Reddy NG, Barkoh BA, Handal B et al. Clinical validation of a next-generation sequencing screen for mutational hotspots in 46 cancer-related genes. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD. 2013;15(5):607-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.05.003.

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK et al. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017;67(2):93-9. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21388.

Vauthey JN, Kopetz SE. From multidisciplinary to personalized treatment of colorectal liver metastases: 4 reasons to consider RAS. Cancer. 2013;119(23):4083-5. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28348.

Chun YS, Passot G, Yamashita S, Nusrat M, Katsonis P, Loree JM et al. Deleterious Effect of RAS and Evolutionary High-risk TP53 Double Mutation in Colorectal Liver Metastases. Annals of surgery. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000002450.

Summers MG, Smith CG, Maughan TS, Kaplan R, Escott-Price V, Cheadle JP. BRAF and NRAS Locus-Specific Variants Have Different Outcomes on Survival to Colorectal Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2017;23(11):2742-9. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1541.

Schirripa M, Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Morvillo M, Bergamo F, Zoratto F et al. Role of NRAS mutations as prognostic and predictive markers in metastatic colorectal cancer. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2015;136(1):83-90. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.28955.

Cercek A, Braghiroli MI, Chou JF, Hechtman JF, Kemeny N, Saltz L et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Patients with Colorectal Cancers Harboring NRAS Mutations. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2017;23(16):4753-60. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0400.

Kawaguchi Y, Lillemoe HA, Vauthey JN. Gene mutation and surgical technique: Suggestion or more? Surgical oncology. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2019.07.004.

Makuch RW. Adjusted survival curve estimation using covariates. Journal of chronic diseases. 1982;35(6):437-43.

Ghali WA, Quan H, Brant R, van Melle G, Norris CM, Faris PD et al. Comparison of 2 methods for calculating adjusted survival curves from proportional hazards models. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(12):1494-7.

Sanchez-Vega F, Mina M, Armenia J, Chatila WK, Luna A, La KC et al. Oncogenic Signaling Pathways in The Cancer Genome Atlas. Cell. 2018;173(2):321-37 e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.035.

Akhoondi S, Sun D, von der Lehr N, Apostolidou S, Klotz K, Maljukova A et al. FBXW7/hCDC4 is a general tumor suppressor in human cancer. Cancer research. 2007;67(19):9006-12. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1320.

Jardim DL, Wheler JJ, Hess K, Tsimberidou AM, Zinner R, Janku F et al. FBXW7 mutations in patients with advanced cancers: clinical and molecular characteristics and outcomes with mTOR inhibitors. PloS one. 2014;9(2):e89388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089388.

Lobry C, Oh P, Mansour MR, Look AT, Aifantis I. Notch signaling: switching an oncogene to a tumor suppressor. Blood. 2014;123(16):2451-9. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-08-355818.

Masuda K, Ishikawa Y, Onoyama I, Unno M, de Alboran IM, Nakayama KI et al. Complex regulation of cell-cycle inhibitors by Fbxw7 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Oncogene. 2010;29(12):1798-809. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2009.469.

Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330-7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11252.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Ruth Haynes for the administrative support in the preparation of this manuscript.

Statement of Author Contribution

Substantial contributions to:

The conception or design of the work: YK, TN, JNV

The acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: YK, TN, HT, CWT, YSH, TA, SK, JNV

Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: all authors

Final approval of the version to be published: all authors

Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: all authors

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant, CA016672.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Nothing to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Previous communication to a society or meeting: This study was presented on June 3, 2020 in the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract Wednesday Webinars due to the cancellation of the 61th Annual Meeting of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract Plenary Session.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figure 1

Patient selection. *In patients who completed 2-stage hepatectomy, only the second-stage hepatectomy was included. The first-stage hepatectomy was excluded not to include patients twice in our analysis. (DOCX 357 kb)

Supplementary Figure 2

Overall survival (OS) by TP53 and FBXW7 alteration status. (A) OS curves. (B) OS curves after adjustment for somatic gene alteration status (BRAF, RAS, and SMAD4), prehepatectomy chemotherapy (> 6 cycles vs. ≤ 6 cycles or no prehepatectomy chemotherapy), number of CLM, and largest liver metastasis diameter. (DOCX 380 kb)

ESM 1

(DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kawaguchi, Y., Newhook, T.E., Tran Cao, H.S. et al. Alteration of FBXW7 is Associated with Worse Survival in Patients Undergoing Resection of Colorectal Liver Metastases. J Gastrointest Surg 25, 186–194 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04866-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-020-04866-2