Abstract

Background

When compatible with the liver functional reserve, laparoscopic hepatic resection remains the treatment of choice for hepatocellular carcinoma while laparoscopic ablation therapies appear as a promising less invasive alternative. The aim of the study is to compare two homogeneous groups of patients submitted to either hepatic resection or thermoablation for the treatment of single hepatocellular carcinoma (≤ 3 cm).

Methods

We enrolled 264 cirrhotic patients out of 905 cases consecutively evaluated for hepatocellular carcinoma. We performed 59 hepatic resections and 205 thermoablations through a laparoscopic approach, and they were then followed for similar follow-up (41.7 ± 31.5 months for laparoscopic hepatic resection vs. 38.7±32.3 for laparoscopic ablation therapy). Outcomes included short- and long-term morbidities, tumoral recurrence, and overall survival.

Results

Short-term morbidity was significantly higher in the resection group (but the two groups had similar rates for severe complications) while, during follow-up, recurrence was more frequent in patients treated with thermoablation, with a clear disadvantage in terms of survival. At multivariate analysis, only the type of surgical treatment was an independent predictor of disease recurrence, while plasmatic alpha-fetoprotein and Hb values, model for end-stage liver disease score, time to recurrence, and the type of surgical treatment were independent predictors of overall survival.

Conclusion

Our data ultimately support some therapeutic advantages for hepatic resection in patients with a single nodule and preserved liver function. However, thermoablation is an adequate alternative in patients with nodules that would require complex surgical resections or imply a poor prognosis that might therefore better tolerate a less invasive procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Liver transplantation, hepatic resection (HR), and percutaneous tumor ablation are considered as curative therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) according to the current EASL/ American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) guidelines.1 Among these, liver transplantation remains the ideal option at earlier stages, yet this choice is significantly limited by the shortage of organ donors and the advanced age of patients at diagnosis. Both HR and ablation therapies influence the natural history of HCC by increasing the survival of patients with a single small-size nodule, but disease recurrence following either treatment remains an issue. Several studies in the literature have compared the outcomes of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and HR,2,3 but there is significant controversy with regard to which modality provides the best outcomes. Laparoscopic ablation therapies (LATs) have been proposed in patients unsuitable to the percutaneous approach as a less invasive technique alternative to HR and provide an ideal comparison setting since both approaches allow the use of intraoperative ultrasonography (IOUS).4 Recent comparative studies5,6,7,8 and a meta-analysis,9 comparing the outcome of HR for HCC using open or minimally invasive surgery, showed how laparoscopic HR (LHR) positively affects the postoperative course, reducing the morbidity rate in cirrhotic patients.

The aim of this study is to compare two mini-invasive approaches (LHR vs. LATs) for the treatment of HCC in terms of postoperative morbidity and long-term results.

Methods

Patient Enrollment

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Milan University. The patient records were anonymized and de-identified prior to analysis, and informed consent to store the clinical data of patients with HCC was obtained from each participant. In our center, all patients with HCC were treated with HR or RFA, as determined by our multidisciplinary tumor board: Even if no liver transplant activity was available in-site, an accurate evaluation by a transplant center was considered; despite the availability of this procedure, it was rather limited until the beginning of the 2000s. Data included in this study came from patients who were treated with either HR or RFA starting from 1998 to January 2017. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) criteria were utilized as a broad framework for deciding appropriate treatment strategies.1 Until 2012 (when the modified BCLC therapeutic algorithm was published), HR was proposed according to BCLC and AASLD guidelines: patients who had a single lesion can be offered surgical resection if they had cirrhosis with preserved liver function. Portal hypertension was not considered a contraindication in all cases.10 When HR was not feasible or warranted, patients were evaluated for percutaneous RFA or LATs. Percutaneous RFA was considered in patients with favorable target tumor (nodule was conspicuous on planning ultrasound (US) for possible percutaneous RFA), at higher surgical risk (more than two segments with a postoperative remnant liver size less than 40–50%), impaired liver function (Child B), or severe comorbidities, whereas LATs were considered for tumors in the dome of the liver, in other dangerous locations (due to the proximity with visceral structures such as the gallbladder, the colon, and the stomach), or in locations difficult to accurately target percutaneously, as confirmed by expert radiologists skilled in interventional procedures. Patients were included in the present cohort analysis if they fulfilled all of the following criteria at presentation, i.e., single lesion, tumor size less than 3 cm, Child-Pugh class A, resection of less than two segments, and only treated once by either LAT or LHR.

Upon referral, patients were tested for liver function including plasma levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), complete blood cell count, and chest X-ray. The residual liver function was classified according to the Child-Pugh classification and by model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score (which was retrospectively recalculated for patients included before 2000),11 while the clinical stage was based on the BCLC staging system.1,12 Comorbidity was assessed using the Charlson’s index13: According to this score, patients were categorized as having slight (< 2) or severe comorbidities (≥ 3). Furthermore, the diagnosis and staging of HCC were achieved by sequential contrast-enhanced imaging studies such as percutaneous ultrasound, triple-phase helical computed tomography (CT), and/or contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Prior to the establishment of the criteria for non-invasive diagnosis of HCC at the European Association of the Study of the Liver in 2000, the diagnosis was established by liver biopsy. As suggested by current guidelines,1 a preoperative ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy was performed only in patients with uncertain diagnosis.

The choice of LHR or LAT was primarily based on the site of the tumor: If it was located in a resectable segment, a LHR was accomplished; if it was ill-located requiring major HR, LAT was indicated.4 Furthermore, laparoscopic approach of RFA permitted to treat deep-sited lesions with very difficult or impossible percutaneous approach.14

Treatment

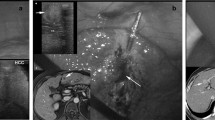

All patients underwent intraoperative ultrasound examination (Aloka Alfa 10; Aloka Co, Tokyo) by surgeons trained in US techniques.4 The laparoscopic ultrasound (LUS) probe had a flexible tip and dimensions of 10 mm in diameter and 50 cm in length. A 7.5 linear-array transducer was side-mounted near the tip of the shaft. The length of the transducer surface was 38 mm, producing an image of approximately 4 cm in length and 6 cm in depth. Each LUS liver exam was performed at the beginning of each surgical procedure, with the patient under general anesthesia.14

For all RFA, a 200-W, 480-KHz monopolar radiofrequency generator (AMICA-GEN, HS Hospital Service SpA, Aprilia, Italy) was used. An insulated 18-gauge internally cooled tip electrode was inserted into the tumor under sonographic guidance. The tip of the electrode was advanced until it reached the lesion and passed its distal margin, opposite to the point of entrance of the needle. Additional RF needle electrodes were inserted into the lesion as needed to cover the entire lesion with adequate margin.

For all microwave ablations (MWA), a 2.45-MHz microwave generator (AMICA-GEN, HS Hospital Service SpA, Aprilia, Italy) was used, also under ultrasound guidance. The generator delivered 40–100 W through a 14- or 16-gauge internally cooled coaxial antenna. This antenna utilized a miniaturized quarter-wavelength tip to improve heating efficiency and ensure a radiation pattern localized to the tip. An automatic peristaltic pump was used to deliver water cooling around the antenna shaft to avoid overheating.

If the lesion was located near major biliary or portal vessels, a cooling technique was accomplished: Continuous infusion/perfusion of gauzes around the hepatic hilum with cold normal saline was done during the LAT procedure to cool the portal inflow and prevent both portal thrombosis and biliary damage.

The technique of LHR has been described elsewhere.15 Briefly, each patient’s position and trocar placement were determined based on the location of the tumor. The patient was positioned in the supine split-leg position, with the surgeon standing between the legs and his assistants at the sides; a left lateral decubitus was employed for right posterior lesions. Pneumoperitoneum was achieved with the open Hasson technique. Laparoscopic hepatectomies were performed with the four- or five-trocar technique, placed according to tumor location. LUS was routinely performed to localize the lesion and evaluate its relationship with the biliary and vascular structures and to delineate the transection plane before the resection. For parenchymal transection, Thunderbeat (Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and bipolar shears were usually employed. Endovascular staplers were used to divide larger vascular pedicles, while bleeding from small vessels was controlled with metal clips or bipolar coagulation. Pringle maneuver was always prepared and used eventually to control bleeding.

Assessment and Follow-Up

Postoperative was defined as the occurrence of death within 30 and 90 days after treatment. The severity of postoperative morbidity was defined according to the Dindo-Clavien classification of surgical complications.16 Liver US and CT (and/or MRI) were performed within 1 month after treatment to assess the response to LATs or HR. Post-treatment follow-up evaluation was performed by spiral CT (and/or MRI) after 1–3 months and every 6 months thereafter.

Technical Evaluation

Technical outcome and oncologic response were defined using the International Working Group on Image-Guided Tumor Ablation17-standardized definitions. Local tumor progression was diagnosed when a follow-up exam showed findings of interval development/growth of the tumor along the margin of the ablation or resected zone where the LATs/LHR had been considered to be technically effective. HCC recurrence was also classified as early or late, using a cutoff of 12 months. Experienced radiologists reviewed all CT or MRI scans.

Statistical Analysis

Cumulative actuarial curves were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared by the log-rank test. Comparison of continuous variables between and within groups was done using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Wilcoxon matched-pair test. Comparison of proportions was done by the Fisher exact probability test. Data following a normal distribution are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; if non-parametric, median and interquartile range (IR) are reported. In all patients, 22 variables were recorded and their influence upon survival and HCC recurrence in each treatment group was assessed by univariate analysis and by either the logistic regression or Cox’s proportional-hazard regression model if the variable is time-related. The association of each parameter with survival and recurrence rates was univariately estimated by comparing actuarial curves (Kaplan-Meier product-limit method and log-rank test) after the categorization of the continuous variables in a multivariate setting. Only parameters with p values < 0.05 were then included in the multivariate analysis. For each parameter analyzed in the multivariate analysis, the t values (hazard ratio) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained. All analyses were two-tailed, and p values < 0.05 were considered as significant throughout the study. Initial evaluation and subsequent follow-up data were collected in a dedicated database (FileMaker Pro for Macintosh, FileMaker Inc., Santa Clara, CA) and subsequently analyzed (Intercooled Stata 14.1 for Macintosh, Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Subjects

Figure 1 illustrates the patient selection process, which led to the present study comparing outcomes in 59 patients who underwent LHR and 205 who underwent LAT. In the same figure, the causes for ineligibility and the alternative treatment options are also reported.

Study design and patient eligibility discrimination process. For all uneligible patients, the exclusion criteria and alternative treatment options are illustrated. pts patients, LPT laparotomic, RFA radiofrequency ablation, LAT laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation, LHR laparoscopic hepatic resection

The baseline characteristics of patients allocated to the LHR and LAT groups are illustrated in Table 1. Despite the non-randomized design of the present study, the two groups were not significantly different for any of the preoperative demographic, clinical (including the Child-Pugh, MELD, and BCLC scores), and biochemical variables with the exception of HCC localization, hemoglobin, and cholinesterase plasma levels.

Surgical Procedures and Findings

Anatomical resection based on the segmental division of the liver was performed in 30 cases (51%), while a US-guided atypical resection was chosen in 29 cases (49%); the Pringle maneuver was used in 3 patients (5%) (total duration with interval maneuver 14 ± 13 min). In the LAT group, a single-electrode technique (RFA) was used in 159 patients (78%) and a cluster-electrode system in 1 case (exposed tip 2.5 cm), while a microwave antenna was used in 44 patients (22%). In 128 patients (62%), a single needle insertion was sufficient while in 66 patients (32%), two needle insertions were sufficient and in 11 (6%) patients, three needle insertions were necessary to obtain adequate tissue coagulation. Mean procedure time for the RFA portion of LAT treatments was 15 ± 5 min and for MWA, it was 8 ± 4 min, while the procedure duration was significantly longer for LHR (165 ± 45 min, median 160, IR 140–200) compared to LAT (78 ± 28 min, median 70, IR 60–90) (p < 0.0001).

During LUS evaluation, 9/59 (15%) patients who underwent LHR were found to have additional lesions (four in a different segment, five within 2 cm of the primary HCC location); of these, four were submitted to enlarged resection and five to ethanol injection. In the LAT group, LUS identified 31/205 (15%) cases with previously undetected lesions (21 in a different segment, 10 within 2 cm of the primary HCC); of these, 25 cases were treated with additional thermoablation and 6 with ethanol injection.

Postoperative Results

Table 2 illustrates the postoperative outcomes at both short and long terms following LHR and LAT. As expected, LHR was characterized by significantly longer admission and higher morbidity rates compared to LAT in the short term (but the two groups had similar rates for severe complications), while morbidity rates became similar during the follow-up period. There were no operative deaths in either group at 30 days. Two patients died in the LHR group within 90 days: one patient for liver failure with diffuse HCC and the other for cerebro-vascular accident.

The margins of all liver resection specimens were negative, except in one case (1.7%). In the LAT group, a complete necrosis was obtained at 1 month in 199/205 (97%) patients: These patients required an additional transarterial chemoembolization in four cases and another thermoablation session in the other two to achieve complete HCC necrosis.

During follow-up, 17/59 (29%) patients in the LHR group and 113/205 (55%) of the LAT group (p = 0.024) died (Table 2). Following similar follow-up durations in the two groups (41.7 ± 31.5 months for LHR vs. 38.7 ± 32.3 for LAT), 24/59 (41%) patients treated with LHR and 135/205 (66%) treated with LAT had HCC recurrence (p = 0.0001). Recurrences in the LHR group did not occur near the surgical margins in any case, while in the LAT group, they occurred near the necrosis area in 30/205 cases (local tumor progression 15%; p = 0.002) with a slight difference between RFA (16%) and MWA (11%; p = NS). The actuarial recurrence rate calculated by the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method in patients treated with LAT was significantly different compared to cases treated with LHR (p = 0.0002) (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the actuarial survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years of follow-up were, respectively, 93, 82, and 56% in the LHR group and 91, 62, and 40% in the LAT group (p = 0.0053) (Fig. 2b). Considering the HCC position a confounding factor, which could affect survival and recurrence rates, a subgroup of patients with only superficial lesions has been analyzed (50 LHR vs. 64 LATs). Also, for these patients, actuarial recurrence and survival rates were significantly different (p = 0.0001 and p = 0.0008, respectively) (Fig. 3).

Probability of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) recurrence (a) and survival (b) actuarial curves comparing surgical resection (LHR) and laparoscopic radiofrequency (LAT) in subgroups of patients with superficial HCC nodules. The differences between these groups were statistically significant for recurrence (p = 0.0001) and overall survival (p = 0.0008)

Table 3 summarizes the results of univariate analysis of the influence of preoperative and intraoperative factors on the recurrence rates and survival among the 264 patients with HCC included in the present study, regardless of the surgical approach. Of note, the choice of LHR or LAT was significantly associated both with HCC recurrence and with patient survival. When a multivariate analysis (Table 4) was performed using variables associated with HCC recurrence at the univariate analysis, only the type of surgical treatment was an independent predictor of disease recurrence. A similar statistical analysis was used to determine what variables were independent predictors of overall survival and demonstrated that plasmatic AFP and Hb values, MELD score, time to HCC recurrence, and the type of surgical treatment significantly predicted survival.

Discussion

The choice of a surgical approach in patients with HCC remains a challenge for the surgeon, the radiologist, and the hepatologist alike. Invasive procedures such as HR remain widely accepted based on the proven impact on prognosis,18,19,20 while promising evidence is growing for all types of RFA which are better tolerated but burdened by higher recurrence rates.21,22 We herein report that in a well-selected series of HCC cases, HCC recurrence rates are mainly determined by the choice of LAT or LHR treatment, while the overall patient survival is determined by individual features including liver function, aggressive tumoral behavior, and also the type of treatment. The major limitation of this study is that the two treatment groups do not have equivalent baseline characteristics, above all regarding the tumor location. It is unclear in the literature if the position of the tumor (superficial or deep location) could influence both recurrence and survival.23 Our subgroup analysis for patients with superficial lesions (which could improve LAT outcomes) showed different recurrence and survival rates between LAT and LHR patients, confirming a clear advantage for the resection group. Other potential confounding factors such as HCC diameter, vascular microinfiltration, or liver functional reserve had equivalent baseline rates.

The BCLC therapeutic algorithm recommended RFA as the first-line treatment option for single HCC nodule ≤ 2 cm, while surgical approach should be considered in patients with failure or contraindications to ablation therapies.1 RFA is more commonly performed percutaneously, thus making its outcome more dependent on the clinical setting or individual factors such as the risk of bleeding and nodule localization.24,25,26 On the other hand, the laparoscopic approach is characterized by further advantages over percutaneous RFA for HCC, particularly since it allows an IOUS study to diagnose otherwise undetected nodules and to provide a better visualization of the tumor and a more accurate placement of the ablation probe.4,14 Furthermore, in the literature, HR is similar to or better than percutaneous RFA in terms of survival, with lower recurrence rates but with higher postoperative complications rates. In this setting, LHR for patients of HCC with cirrhosis seems to suffer lower morbidity rates which were usually reported in open HR7,11 and this justifies the similar rates of severe postoperative complications in this study. For these reasons, we were convinced that the LHR outcomes were to be compared to LAT, rather than percutaneous RFA, particularly in patients with compensated (i.e., Child A) liver cirrhosis.

In literature, five studies compared LHR with RFA (three through a percutaneous access27,28,29 and two through a laparoscopic approach30,31). The studies comparing LHR with percutaneous RFA showed that LHR had similar morbidity but fewer recurrences. As regards to the other two studies, Casaccia et al.30 showed a higher survival rate for the LHR group, but the small sample size and different preoperative characteristics do not permit definitive conclusions. Yazici’s study31 is limited to elderly patients (> 65 years), and it showed similar morbidity and overall survival rates but higher local recurrences after LAT. Also, this study has some limitations such as the small size and heterogeneity of tumor type between the LHR and LAT groups.

Despite the good rates of technical success after LAT (97% of total necrosis at 1 month), our univariate comparisons demonstrate that LHR led to lower recurrence rates (particularly for the local tumor progression) compared to LAT in patients with Child-Pugh A liver cirrhosis and a single small HCC nodule (less than 3 cm). The multivariate model also confirmed this view of HCC recurrence. This is in accordance with the concept of anatomic resection and intrahepatic dissemination through the portal vein branches32,33 with the resection of HCC and its portal venous territory, reducing the risk of HCC local tumor progression.34 When the liver function is adequate, anatomically systematic LHR or atypical resections with wide margins lead to HCC-free surgical margins that may otherwise contain non-detectable micrometastases due to vascular infiltration.35 The possibility of distant intrahepatic HCC recurrences, however, supports a metachronous multicentric hepatocarcinogenesis in the remnant liver36,37 and further proves that recurrence shares two possible etiologies: i.e., via metastases or as new primary lesions. This concept is the rationale for liver transplantation in small HCC38 and prompted some authors to advocate interstitial therapies such as less invasive procedures as efficient as LHR.39

Our data showed that LHR had higher survival rates in patients with single-nodule HCC and preserved liver function. In the Cox model, as well as the type of treatment, elevated baseline serum AFP (> 20 ng/ml), MELD (> 9), and an early recurrence (<12 months) were independent determinants of poor overall survival. Several studies showed that MELD score could accurately predict mortality, morbidity, and long-term survival in patients with HCC and cirrhosis undergoing HR.40,41 In our study, it is evident that a MELD score > 9 is an independent predictive factor of survival, irrespective of the type of HCC treatment and it is an expression of latent liver failure.42 Serum AFP levels likely reflect the degree of HCC differentiation and thus the risk of spreading, and its importance as an HCC prognostic factor has been shown in several studies.43 We also confirmed previous data that there is an independent association between the time interval to recurrence and survival.44 Based on the poor prognosis of early recurrences, a stringent follow-up and a prompt treatment of recurrences are critical to ameliorate long-term survival.45

Our study furnished interesting information despite the absence of prospective randomization, as in the vast majority of surgical comparisons. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest comparative study between two laparoscopic treatments including all covariates that could affect the outcomes. Our stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria led to similar preoperative patient features in the two groups, particularly for established prognostic factors (i.e., gender, age, HCC pattern and staging, and liver function) with the expected exception of HCC localization. Further exploration into the role of HCC location would be important in the evaluation of these two modalities; however, a direct analysis of a subgroup of patients with superficial tumors seems to show the same results of the entire group. Indeed, the choice of LHR or LAT in enrolled patients was ultimately made after a multidisciplinary evaluation, based on the nodule localization, and LAT was performed in cases in which the HCC nodule could not be safely treated by LHR. Furthermore, the use in all cases of IOUS with a high-frequency transducer placed directly onto the liver surface should be regarded as a major strength since it allows the detection of previously undetected small tumor nodules and their intraoperative treatment in both groups.

There are a number of limitations of the study. These include the retrospective analysis and heterogeneity of tumor location between the LAT and LHR groups. Nevertheless, the main objective was to see how cirrhotic patients would tolerate a LHR better than open resection in comparison with LAT and we believe that the study provides some insight into this question, with the two groups having similar demographic and comorbidity profiles.

Despite these limitations, our data ultimately support some therapeutic advantages for LHR in patients with a single HCC nodule and preserved liver function compared to LAT, in agreement with data in percutaneous RFA.11 However, we suggest that LAT is an adequate alternative in patients with nodules that would require complex surgical resections or imply a poor prognosis that might therefore better tolerate a less invasive procedure, which also constitutes an ideal bridge to liver transplantation.46

Abbreviations

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- LHR:

-

Laparoscopic hepatic resection

- LAT:

-

Laparoscopic ablation therapy

- HR:

-

Hepatic resection

- RFA:

-

Radiofrequency ablation

- MWA:

-

Microwave ablation

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- Pts:

-

Patients

- LPT:

-

Laparotomic

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- LUS:

-

Laparoscopic ultrasound

- IR:

-

Interquartile range

References

Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2012; 379: 1245–55

Feng Q, Chi Y, Liu Y, Zhang L, Liu Q. Efficacy and safety of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation versus surgical resection for small hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of 23 studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015; 141: 1–9

Kutlu O, Chan JA, Aloia TA, Chun YS, Kaseb AO, Passot G, Yamashita S, Vauthey JN, Conrad C. Comparative effectiveness of first-line radiofrequency ablation versus surgical resection and transplantation for patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2017; 123: 1817–1827

Santambrogio R, Barabino M, Bruno S, Costa M, Pisani Ceretti A, Angiolini MR, Zuin M, Meloni F, Opocher E. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic ablation therapies for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a single European center experience of 426 patients. Surg Endosc 2016; 30: 2103–2113

Ahn KS, Kang KJ, Kim Y, Kim TS, Lim TJ. A propensity score-matched case-control comparative study of laparoscopic and open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2014; 24: 872–877

Kim H, Suh KS, Lee KW, Yi NJ, Hong G, Suh SW, Yoo T, Park MS, Choi YR, Lee HW. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic versus open liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-controlled study with propensity score matching. Surg Endosc 2014; 28: 950–960

Aldrighetti L, Belli G, Boni L, Cillo U, Ettorre G, De Carlis L, Pinna A, Casciola L, Calise F, Italian Group of Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery. Italian experience in minimally invasive liver surgery: a national survey. Updates Surg 2015; 67: 129–140

Tanaka S, Takemura S, Shinkawa H, Nishioka T, Hamano G, Kinoshita M, Ito T, Kubo S. Outcomes of pure laparoscopic versus open hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: a case-control study with propensity score matching. Eur Surg Res 2015; 55: 291–301

Zhou Y, Shao Y, Zhao YF, Xu DH, Li B. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic versus open resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56: 1937–1943

Santambrogio R, Kluger MD, Costa M, Belli A, Barabino M, Laurent A, Opocher E, Azoulay D, Cherqui D. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with Child-Pugh’s A cirrhosis: is clinical evidence of portal hypertension a contraindication? HPB 2013; 15: 78–84

Santambrogio R, Bruno S, Kluger MD, Costa M, Salceda J, Belli A, Laurent A, Barabino M, Opocher E, Azoulay D, Cherqui D. Laparoscopic ablation therapies or hepatic resection in cirrhotic patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis 2016; 48: 189–196

Bruix J, Llovet JM. Prognostic prediction and treatment strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2002; 35:519–524.

Simons JP, Hill JS, Ng SC, Shah SA, Zhou Z, Whalen GF, Tseng JF. In-hospital mortality from liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer 2010; 116:1733–8

Santambrogio R, Bianchi P, Pasta A, Palmisano A, Montorsi M. Ultrasound-guided interventional procedures of the liver during laparoscopy: technical considerations. Surg Endosc 2002; 16:349–354.

Santambrogio R, Aldrighetti L, Barabino M, Pulitanò C, Costa M, Montorsi M, Ferla G, Opocher E. Laparoscopic liver resections for hepatocellular carcinoma. Is it a feasible option for patients with liver cirrhosis? Langenbecks Arch Surg 2009; 394: 255–64

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications. A new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 633 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205–13

Ahmed M. Image-guided tumor ablation: standardization of terminology and reporting criteria—a 10-year update. Radiology 2014; 273: 241–260

De Lope CR, Tremosini S, Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Management of HCC. J Hepatol 2012; 56 (suppl 1): S75–87

Roayaie S, Obeidat K, Sposito C, Mariani L, Bhoori S, Pellegrinelli A, Labow D, Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection of hepatocellular cancer ≤2 cm: results from two Western Centers. Hepatology 2013; 57: 1426–1435

Lee JI, Lee JW, Kim YS, Choi YA, Jeon YS, Cho SG. Analysis of survival in very early hepatocellular carcinoma after the resection. J Clin Gastroenterol 2011; 45: 366–71

Ding J, Jing X, Wang Y, Wang F, Wang Y, Du Z. Thermal ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a large-scale analysis of long-term outcome and prognostic factors. Clin Radiol 2016; 71: 1270–1276

Colecchia A, Schiumerini R, Cucchetti A, Cescon M, Taddia M, Marasco G, Festi D. Prognostic factors for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence World J Gastroenterol 2014; 28: 5935–5950

Jia JB, Zhang D, Ludwig JM, Kim HS. Radiofrequency ablation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with Child-Pugh A liver cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Clin Radiol 2017; 72:1066–1075

Kim PN, Choi D, Rhim H, Rha SE, Hong HP, Lee J, Choi J, Kim JW, Seo JW, Lee EJ, Lim HK. Planning ultrasound for percutaneous radiofrequency ablation to treat (<3 cm) hepatocellular carcinomas detected on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging: a multicenter prospective study to assess factors affecting ultrasound visibility. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012; 23: 627–634

Kim JE, Kim YS, Rhim H, Lim HK, Lee MW, Choi D, Shin SW, Cho SK. Outcomes of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma referred for percutaneous radiofrequency ablation at a tertiary center: analysis focused on the feasibility with the use of ultrasonography guidance. Eur J Radiol 2011; 79: e80-e84

Rhim H, Lee MH, Kim YS, Choi D, Lee WJ, Lim HK. Planning sonography to assess the feasibility of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinomas. AJR 2008; 190: 1324–1330

Bauschke A, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Mothes H, Rauchfuss F, Settmacher U. Partial liver resection results in a significantly better long-term survival than locally ablative procedures even in elderly patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2016; 142: 1099–1108

Song J, Wang Y, Ma K, Zheng S, Bie P, Xia F, Li X, Li J, Wang X, Chen J. Laparoscopic hepatectomy versus radiofrequency ablation for minimally invasive treatment of single, small hepatocellular carcinoma. Surg Endosc 2016; 30: 4249–4257

Vitali GC, Laurent A, Terraz S, Majno P, Buchs NC, Rubbia-Brandt L, Luciani A, Calderaro J, Morel P, Azoulay D, Toso C. Minimally invasive surgery versus percutaneous radio frequency ablation for the treatment of single small (≤3 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study. Surg Endosc 2016; 30: 2301–2307

Casaccia M, Santori G, Bottino G, Diviacco P, Andorno E. Laparoscopic resection vs laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas: a single-centre analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 653–660

Yazici P, Akyuz M, Yigitbas H, Dural C, Okoh A, Aydin N, Berber E. A comparison of perioperative outcomes in elderly patients with malignant liver tumors undergoing laparoscopic liver resection versus radiofrequency ablation. Surg Endosc 2017; 31: 1269–1274

Makuuchi M, Hasegawa H, Yamazaki S. Ultrasonically guided subsegmentectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1985;161:346–350.

Torzilli G, Montorsi M, Donadon M, Palmisano A, Del Fabbro D, Gambetti A, Olivari N, Makuuchi M. “Radical but conservative” is the main goal for ultrasonography-guided liver resection: prospective validation of this approach. J Am Coll Surg 2005; 201: 517–28

Yamashita Y, Tsuijita E, Takeishi K, Fujiwara M, Kira S, Mori M, Aishima S, Taketomi A, Shirabe K, Ishida T, Maehara Y. Predictors for microinvasion of small hepatocellular carcinoma ≤2 cm. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 2027–34

Shimada S, Kamiyama T, Yokoo H, Orimo T, Wakayama K, Einama T, Kakisaka T, Kamachi H, Taketomi A. Clinicopathological characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma with microscopic portal venous invasion and the role of anatomical liver resection in these cases. World J Surg 2017; 41: 2087–2094

Shimada M, Hasegawa H, Gion T, Shirabe K, Taguchi K, Takenaka K, Tanaka S, Sugimachi K. Risk factors of the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma originating from residual cancer cells after hepatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology 1999; 46:2469–2475.

Adachi E, Maehara S, Tsujita E, Taguchi K, Aishima S, Rikimaru T, Yamashita Y, Tanaka S. Clinicopathologic risk factors for recurrence after a curative hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery 2002; 31:S148–152.

Fabrega JF, Forner A, Liccioni A, Miquel R, Molina V, Navasa M, Fondevila C, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Bruix J, Fuster J. Prospective validation of ab initio liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma upon detection of risk factors for recurrence after resection. Hepatology 2016; 63: 839–49

Livraghi T, Meloni F, Di Stasi M, Rolle E, Solbiati L, Tinelli C, Rossi S. Sustained complete response and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology 2008; 47: 82–89

Delis SG, Bakoyiannis A, Biliatis I, Athanassiou K, Tassopoulos N, Dervenis C. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score, as a prognostic factor for post-operative morbidity and mortality in cirrhotic patients, undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma HPB 2009; 11: 351–357

The SH, Christein J, Donohue J, Que F, Kendrick M, Farnell M, Cha S, Kamath P, Kim R, Nagorney DM. Hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: model of end-stage liver disease (MELD) score predicts perioperative mortality. J Gastrointest Surg 2005; 9: 1207–1215

Peng Y, Qi X, Guo X. Child-Pugh versus MELD score for the assessment of prognosis in liver cirrhosis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine 2016; 95: e2877

Santambrogio R, Opocher E, Costa M, Barabino M, Zuin M, Bertolini E, De Filippe F, Bruno S. Hepatic resection for “BCLC stage A” hepatocellular carcinoma. The prognostic role of alpha-fetoprotein. Ann Surg Oncol 2012; 19: 426–434

Lee S, Kwon CHD, Kim JM, Joh JW, Paik SW, Kim BW, Wang BW, Wang HJ, Lee KW, Suh KS, Lee SK. Time of hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver resection and alpha-fetoprotein are important prognostic factors for salvage liver transplantation. Liver Transplant 2014; 20: 1057–1063

Shah SA, Cleary SP, Wei AC, Yang I, Taylor BR, Hemming AW, Langer B, Grant DR, Greig PD, Gallinger S. Recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: risk factors, treatment, and outcomes. Surgery 2007;141:330–339.

Lee MW, Raman SS, Asvadi NH, Siripongsakun S, Hicks RM, Chen J, Worakitsitisatorn A, McWilliams J, Tong MJ, Finn RS, Agopian VG, Busuttil RW, Lu DSK. Radiofrequency abaltion of hepatocellular carcinoma as bridge therapy to liver transplantation: a 10-year intention-to-treat analysis. Hepatology 2017; 65: 1979–1990

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Santambrogio, R., Barabino, M., Bruno, S. et al. Surgical Resection vs. Ablative Therapies Through a Laparoscopic Approach for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: a Comparative Study. J Gastrointest Surg 22, 650–660 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-017-3648-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-017-3648-y