Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this prospective study was to analyze the impact of different surgical techniques on patients undergoing intestinal surgery for Crohn’s disease (CD) in terms of recovery, quality of life, and direct and indirect costs.

Patients and methods

Forty-seven consecutive patients admitted for intestinal surgery for CD were enrolled in this prospective study. Surgical procedures were evaluated as possible predictors of outcome in terms of disability status (Barthel’s Index), quality of life (Cleveland Global Quality of Life score), body image, disease activity (Harvey–Bradshaw Activity Index), and costs (calculated in 2008 Euros). Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed.

Results

Significant predictors of a long postoperative hospital stay were the creation of a stoma, postoperative complications, disability status on the third post-operative day, and surgical access (R 2 = 0.59, p < 0.01). Barthel’s index at discharge was independently predicted by laparoscopic-assisted approach, ileal CD, and colonic CD (R 2 = 0.53, p < 0.01). The disability status at admission showed to be an independent predictor of quality of life score at follow-up. The overall cost for intestinal surgery for CD was 12,037 (10,117–15,795) euro per patient and stoma creation revealed to be its only predictor (p = 0.006).

Conclusions

Laparoscopy was associated with a shorter postoperative length of stay; stoma creation was associated with a long and expensive postoperative hospital stay, and stricturoplasty was associated with a slower recovery of bowel function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Eighty percent of patients affected by Crohn’s disease (CD) will require at least one surgical procedure over their lifetime.1 Surgery is among the most important concerns of patients affected by CD. In fact, concerns about having surgery and having an ostomy bag have a significant impact on health-related quality of life (HRQL) of CD patients, and having surgery increases concerns about body stigma.2–4

Minimally invasive surgery and stricturoplasty may reduce the negative impact of surgery in these patients. However, extensive colonic resection and/or stoma creation are still necessary in some cases. The early impact of surgery on HRQL is an important component of the patient’s decisions regarding immediate and future surgery and understanding his or her recovery. Obviously, HRQL is expected to improve after operative procedures. In most studies, a significant improvement in HRQL early in the postoperative period was observed.5–7 Improvement, occurred irrespective of the disease activity measured with CDAI, the indication for surgery, type of procedure (abdominal or perineal), and history of previous surgery.8 The impact on HRQL of recovery and namely the disability status of patients after surgery for CD have never been analyzed.

Hospitalization has been estimated to account for half of all direct medical costs for CD9 and half of hospitalized CD patients undergo intestinal surgery.9–11 In fact, of the total charges incurred by patients with CD admitted to the University of Chicago hospitals over a 12-month period, nearly 40% of costs were for surgical management.9 In the Markov analysis by Silverstein et al. estimated charges were higher for patients requiring surgery but the duration of post-surgical remission was longer than for medically treated patients.12 There are few data available to allow a prediction of the costs of surgical treatment and prospective, longitudinal studies addressing this question would be of interest.13

This prospective study aimed to analyze the impact of different surgical techniques on patients who underwent to intestinal surgery for CD in terms of recovery, quality of life, and direct and indirect costs.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The study was performed according to the Helsinki declaration principles and all patients gave their informed consent to be enrolled in the study. Forty-seven consecutive patients admitted for intestinal surgery for CD in our department from May 2006 to July 2008 were enrolled in this prospective study. Diagnosis of CD was made with clinical, endoscopic, and blood tests according to Lennard–Jones criteria.14 Clinical disease activity was quantified using a modified version of the Harvey–Bradshaw Activity Index (HBAI).15 Patients who were admitted for surgery for perineal CD were excluded because of the different surgical procedures and the important impact on quality of life of this disease location.

Study Design

Surgical predictors, such as laparoscopic-assisted bowel resection, stricturoplasty, stoma creation, ileal resection, and colonic resection as well as clinical predictors, such as age, gender, CD duration, activity and localization, and recurrent CD were evaluated. Postoperative course was evaluated with recovery parameters such as day of first bowel movement, postoperative hospital stay, and Barthel’s physical disability score and complication analysis (medical and surgical complication and need of reoperation). After at least 3 months, patients were interviewed about their time to return to work, their disease activity, and they were submitted the Italian version of Cleveland Global Quality of Life (CGQL) score and the Body Image Score.

Surgical Technique

Bowel resection was performed removing all grossly involved bowel through a standard midline laparotomy or with laparoscopic assistance. In the laparoscopic-assisted ileo-colonic resection a three-trocar approach was used (subumbilical, 10 mm; left iliac fossa, 10 mm; suprapubic, 5 mm). The distal ileum and the right colon were fully mobilized and exteriorized by a 4–6 cm vertical incision through the umbilicus. In case of entero-sigmoid fistula or large inflammatory mass, a small Pfannestiel incision (8 cm) was used instead of the transumbilical incision (22). Vascular ligation, bowel division and anastomosis were performed extracorporeally. Stapled anastomoses were constructed in a side-to-side fashion using an 80-mm linear stapler (GIA75, US Surgical Corp., Norwalk, CT, USA). Hand-sewn anastomoses were created in a side-to-side orientation using a running suture of 3–0 Vicryl for the inner layer (mucosal) (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA) and a running 3–0 TiCron (US Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA) for the outer layer (sero-muscolar).

End ileostomy was typically used in cases of extensive colonic CD with macroscopic rectal disease, not responding to medical therapy. The ileal loop was delivered through a trephine in the abdominal wall. After closure of the laparotomy, the ileostomy was opened and the proximal component of loop was everted and then fixed to the skin with muco-cutaneous absorbable 3–0 Vicryl, (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA) sutures. No stitches were placed to fix the ileostomy to the inner layer of the abdominal wall.

Stricturoplasty was constructed in case of ileal or jejunal skip lesions in order to minimize the extent of small bowel resected. The main site of disease (i.e. the ileo-colonic junction) was usually resected and in case of multiple disease sites, standard stricturoplasty was performed. The bowel was incised along its main axis on the anti-mesenteric side on a Crohn’s stenosis and sutured transversally with absorbable 3–0 Vicryl, (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA) stitches.

Barthel’s Index

Barthel’s Index provides an objective assessment of overall disability16 and has been shown to be reliable with different observers in a wide variety of situations. It is a validated measure of physical disability17 initially used in neurological setting but now commonly used to assess the disability of patients in order to optimize nursing assistance. The assessment was independently made by ward staff during their regular rounds a minimum of three times, including on admission, on the third postoperative day, and at discharge.

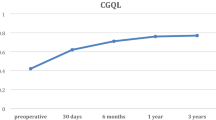

Italian CGQL

The Cleveland Global Quality of Life instrument or Fazio score, developed to assess health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and with CD,18,19 consists of three items (current quality of life, current quality of health, and current energy level), each on a scale of 0 to 10 (with 0 the worst and 10 the best). Given its short framework, the Italian translation, recently validated in one of our previous studies20 was considered a suitable instrument for telephone interviews.

Body Image Questionnaire

The Body Image Questionnaire (BIQ) is an instrument that explores body image and cosmesis after surgery and consists of eight items. The BIQ has already been tested in patients undergoing open and laparoscopic-assisted intestinal surgery.21 The questionnaire consists of two sections concerning body image and cosmesis. The body image scale analyzes patients’ perception of and satisfaction with their own body and investigates patients’ attitudes toward their appearance. The reliability coefficients (values of Cronbach’s alpha) for body image was 0.80.

Cost Analysis

The following assumptions were used as the basis for determining the cost analysis of the different surgical procedures. The median cost of the hospital stay and that of the operation were based on estimates of standard charges in an Italian setting (North-Eastern Italy) and were expressed in 2008 Euros. The daily cost of the hospital stay was estimated to be 960 euro per patient; the cost of the instruments for an open intestinal resection was 603.26 euro while that for a laparoscopic-assisted intestinal resection was 1,477.26 euro per patient. The social cost of lost working days was calculated based on standard Italian daily wages according to the different jobs. Patients were asked about their job and their mean monthly income were retrieved from Italian Ministry of Work database; housewives, retired patients, and students were considered to have no income. The overall cost was calculated by adding the cost of the hospital stay, the cost of the instruments necessary for the operation and the cost of the lost working days during sick leave.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as median value (range) unless otherwise specified. Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U two-tailed test and Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA were used to compare dichotomous variables. Wilcoxon test and Friedman ANOVA were used in the case of paired data. Frequency analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test. Kendall rank correlation test was used to analyze the correlation between predictors and continuous outcome parameters. Given a level of statistical significance (α) of 0.05, a power (1-β) of 0.80 and an expected correlation coefficient of 0.45, the consequent sample size required was 36 patients. Multiple linear regression models were constructed with predictors that were found to be significant on univariate analysis to assess the different role of each one. When the number of predictors exceeded 5, stepwise forward regression analysis was used. R 2 of each model, which is the proportion of variation in the duration of post-operative hospital explained by this model, was shown. Statistical significance was indicated by p < 0.05.

Results

Patients

Median age of the patients was 38 (16–69) years and 23 (49%) of the patients were female. The median duration of CD was 79 (3–264) months, and 11 patients presented a fistulizing phenotype. CD was localized to the small bowel in 38 patients and in the large bowel in nine patients; seven patients had disease in both locations. In addition, four patients had also perineal CD but this was not the main indication for their surgery. Six patients had a stoma (five end ileostomy and a loop ileostomy) created at the time of surgery: five of them for severe colonic CD not responding to medical therapy, and one loop ileostomy proximal to a colo-rectal anastomosis. Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Predictors of Post-operative Recovery and Complications

In this series, the median time of first bowel movement was on the third (first to sixth) postoperative day. Patients who had stricturoplasty had their first bowel movement later than those who had bowel resection (p = 0.042). The timing of the first bowel movement correlated significantly with the obstructing phenotype of CD and with stricturoplasty but none of them was found to be an independent predictor at multiple regression analysis.

The median postoperative stay was 7 (5–20) days and, as shown in Table 2, was significantly shorter in the group of patients who had ileal resection, and in those who underwent laparoscopic-assisted bowel resection. On multiple regression analysis creation of a stoma, postoperative complications, and disability status on the third post-operative day and open (non-laparoscopic) surgery were found to be significant predictors of duration of post-operative hospital stay (R 2 was 0.59, p < 0.01).

Median Barthel’s score at admission was 100 (0–100), on the third postoperative day was 45 (0–100), and at discharge was 100 (30–100; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Barthel’s score on the third post-operative day and at discharge was significantly lower in patients who had a stoma created. Barthel’s score on the third postoperative day significantly correlated with number of intestinal sites involved by CD, stoma creation, perianal CD, and with postoperative day of first bowel movement. However, none of these parameters were found to be an independent predictor at multivariate analysis. However, Barthel’s score at discharge was independently predicted by laparoscopic-assisted approach, ileal CD, and colonic CD (R 2 = 0.53, p < 0.01).

In this series, two anastomotic leaks, three intestinal obstructions, two intestinal bleeding, and a wound infection were recorded and two re-laparotomies were necessary in the post-operative period. Surgical complications correlated inversely with stricturoplasty and Barthel’s Index score at admission but none of these parameters were found to be an independent predictor at multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Predictors of Quality of Life

Median sick leave was 30 (2–360) days and showed a trend to be significantly longer in patients who had surgery other than ileal resection and in those who had a stoma created. However at multiple regression analysis only physical burden of the job appeared to predict independently the sick leave duration.

After follow-up, CGQL score correlated with the Harvey–Bradshaw Activity Index, with surgical complications, and with the Barthel’s Index at admission. At multiple regression analysis only the disability status at admission to the hospital was shown to be an independent predictor of the health-related quality of life score. No significant difference in terms of health-related quality of life was observed between patients who underwent laparoscopic-assisted colonic resection and those who had the same procedure performed open. The analysis of the late parameters of recovery is shown in Table 4.

At 3 months follow-up, BIQ score showed a trend to be higher in patients who had a laparoscopic-assisted intestinal surgery for CD and it was independently predicted by the disease activity, namely by HBAI (p = 0.006), and by the use of laparoscopic-assisted surgery (p = 0.036). BIQ scores predictors are shown in Table 4.

Predictors of Cost of Surgery for CD

The median cost of the hospital stay was 9,120 (7,680–11,520) euro per patient and that of the operation was estimated at 1,477 euro per patient. The social cost of the lost income due to hospital stay and sick leave was estimated to be 750 (0–2,130) euro per patient, therefore the overall cost for intestinal surgery for CD was 12,037 (10,117–15,795) euro per patient. The overall cost correlated directly with colonic resection, surgical complications onset, and with stoma creation. However, at multiple regression analysis only stoma creation was revealed to be an independent predictor (p = 0.006) for overall costs. Patients who had an ileostomy reported significantly higher overall costs and higher costs for the hospital stay (p = 0.050 and p = 0.017, respectively). Patients who had laparoscopic-assisted bowel resection reported significantly lower costs for the hospital stay (p = 0.021), but the overall costs were not different compared to those reported by patients who had open surgery. The analysis of cost of surgery for CD is shown in Table 5.

Discussion

More than the 75% of patients affected by CD undergo some sort of surgery over their lifetime.1 Although minimally invasive surgery and stricturoplasty have reduced the impact of surgery, extensive bowel resection and/or stoma creation may be still necessary, and is relevant to the HRQL of patients affected by CD.2–4 Moreover, the burden of surgery on patients with CD is not only limited to quality of life of patients affected and their relatives, but it is also a significant economic burden. In fact, in 1994, the direct costs associated with hospitalization for CD in Sweden amounted to approximately 7.8 million US dollars/year10 and nearly 40% of all direct medical costs for CD were for surgical management.9 Therefore, this prospective study aimed to analyze the impact of different surgical techniques on patients undergoing intestinal surgery for CD in terms of recovery, quality of life, and direct and indirect costs.

The laparoscopic-assisted approach for intestinal surgery for CD was associated with a significantly shorter postoperative hospital stay and a slightly better Barthel’s score at discharge than open intestinal surgery. Although this was not a randomized study, the Barthel’s score at admission was similar in patients who had open and those who had laparoscopic surgery. Therefore, since this study was conducted out of any fast track setting, the earlier timing of discharge of these patients could be actually attributed to the faster recovery after laparoscopic approach. Moreover, the BIQ score after 3 months follow-up after intestinal surgery for CD was independently predicted by the use of laparoscopic-assisted approach. These data confirm observations by Dunkers et al. in 1998.21 Despite the positive impact on body image, no improvement was detected in overall quality of life. In fact, in our series, no significant difference in terms of health-related quality of life was observed between patients who underwent laparoscopic-assisted colonic resection and those who had the same procedure performed open. This confirms the data of the Amsterdam group that in a randomized controlled trial concluded that generic quality of life was not different for laparoscopic-assisted compared with the open ileocolic resection.22 Moreover, as McLeod et al. had already showed in patients with severe ulcerative colitis, in an our pervious study we showed that quality of life after surgery for CD appeared to be a function of therapeutic efficacy rather than of the surgical procedure used.19,23 Laparoscopic surgery aims to reduce the need for large abdominal incisions with potential benefits both in terms of reduced hospital stay, recovery time, and ‘cosmetic’ result; however, data on cost effectiveness are limited.24 In our series, the overall costs for open and laparoscopic-assisted surgery were medially higher that those reported by Maartense et al. probably because sick leave costs were included in the final count.22 Moreover, differently from what observed by Maartense et al., in our series, patients who had laparoscopic-assisted surgery reported significantly lower costs for the hospital stay, but the overall costs were not different compared to those reported by patients who had open surgery, probably due to the higher costs of the surgical procedure itself outside a controlled clinical trial.22

The creation of a stoma during intestinal surgery for CD was found to be among the significant predictors of duration of post-operative hospital stay, and the Barthel’s Index score on the third postoperative day and at discharge was significantly lower in patients who had a stoma created. Moreover, median sick leave seemed to be longer in patients who had a stoma created even if at multiple regression analysis only the physical burden of the job independently predicted sick leave duration. Curiously, although stoma creation was clearly associated with a slower recovery and it took time for patients to adapt to the new body situation,25 it did not predict poor quality of life. In fact, although this concern has been rated among the most important factors in other studies of patients with CD,26,27 in our series an ostomy bag did not seem to influence the early postoperative quality of life. On the other hand, failure to find significance in the quality of life associated with ostomy creation may be due to the small number of patients who had stoma. In addition, the slower recovery of patients who had stoma creation may be due also to their worse condition that leaded to a more aggressive surgery. In fact, the need for more aggressive surgery and the longer time to recovery were directly reflected by the overall cost of the procedure which correlated directly and independently with stoma creation. Therefore, patients who had an ostomy created reported significantly higher overall costs and higher costs for the hospital stay.

In our series, the first bowel movement occurred later in patients who had stricturoplasty than in those who had bowel resection. Although stricturoplasty is an effective means of alleviating obstructive Crohn's disease while conserving bowel length, it is associated with a 4.4% rate of obstruction and late recovery of the intestinal function in the immediate postoperative period.28 In spite of a recent meta-analysis showing that after jejuno-ileal stricturoplasty septic complications occurred in 4% of patients,29 in our series stricturoplasty seemed to correlate inversely with postoperative surgical complications. However, at multivariate analysis this unexpected association was not confirmed. In fact, stricturoplasty did not seem to have any influence on recovery, nor on the economic burden of surgery. In particular, despite the prolonged postoperative ileus stricturoplasty did not seem to affect the early postoperative quality of life, as already described in a retrospective German study.30

The main limit of this study is the relatively small group of patients and multiple different operations that makes the risk of error in statistical evaluation concrete. All consecutive patients presenting to our department for surgery for CD were enrolled to improve the sample size but the heterogeneity of manifestation of CD leaded to different surgical procedures. Therefore, a confirmatory multicentric study might be warranted after the results obtained with this small series.

In conclusion, the laparoscopic-assisted approach to intestinal surgery for CD was associated with a significantly shorter postoperative hospital stay, stoma creation was associated with a long and expensive postoperative hospital stay, and stricturoplasty was associated with a slower recovery of bowel function. Finally, health-related quality of life appeared to be unrelated to the type of surgical procedure adopted and it seemed related only to the disability status of the patients.

References

Singleton JW, Law DH, Kelley ML Jr, Mekhjian HS, Sturdevant RA. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study: adverse reactions to study drugs. Gastroenterology 1979;77:870–882.

Mussell M, Bocker U, Nagel N, Singer MV. Predictors of disease-related concerns and other aspects of health-related quality of life in outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16:1273–1280.

Etienney I, Bouhnik Y, Gendre JP, Lemann M, Cosnes J, Matuchansky C, Beaugerie L, Modigliani R, Rambaud JC. Crohn’s disease over 20 years after diagnosis in a referral population. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2004;28:1233–1239.

Canavan C, Abrams KR, Hawthorne B, Drossman D, Mayberry JF. Long-term prognosis in Crohn’s disease: factors that affect quality of life. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:377–385.

Tillinger W, Mittermaier C, Lochs H, Moser G. Health-related quality of life in patients with Crohn’s disease. Influence of surgical operation—a prospective trial. Dig Dis Sci 1999;44:932–938.

Thirlby RC, Land JC, Fenster LF, Lonborg L. Effect of surgery on health related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Surg 1998;133:826–832.

Yazdanpanah Y, Klein O, Gambiez L, Baron P, Desreumaux P, Marquis P, Cortot A, Quandalle P, Colombel JF. Impact of surgery on quality of life in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:1897–1900.

Delaney CP, Kiran RP, Senagore AJ, O'Brien-Ermlich B, Church J, Hull TL, Remzi FH, Fazio VW. Quality of life improves within 30 days of surgery for Crohn’s disease. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:714–721.

Cohen RD, Larson LR, Roth JM, Becker RV, Mummert LL. The cost of hospitalisation in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterology 2000;95:524–530.

Blomqvist P, Ekbom A. Inflammatory bowel disease: health care and costs in Sweden in 1994. Scand J Gastrenterol 1997;32:1134–1139.

Bernstein CN, Papineau N, Zajaczkowski J, Rawsthorne P, Okrusko G, Blanchard JF. Direct hospital costs for patients with inflammatory bowel disease in a Canadian tertiary care university hospital. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:677–683.

Silverstein MD, Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Feagan BG, Nietert PJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Clinical course and costs of care for Crohn’s disease: Markov Model analysis of a population-based cohort. Gastroenterology 1999;117:49–57.

Bodger K. Cost of illness of Crohn’s disease. Pharmacoeconomics 2002;20:639–652.

Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 1989;170:2–6.

Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s disease activity. Lancet 1980;1(8167):514.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. MD State Med J 1965;14:61–65.

Wade DT, Hewer RL. Functional abilities after stroke: measurement, natural history and prognosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987;50:177–182.

Kiran RP, Delaney CP, Senagore AJ, O'Brien-Ermlich B, Mascha E, Thornton J, Fazio VW. Prospective assessment of Cleveland Global Quality of Life and disease activity in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1783–1789.

Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, D'Incà R, Filosa T, Bertin E, Ferraro S, Polese L, Martin A, Sturniolo GC, Frego M, D'Amico DF, Angriman I. Health related quality of life after ileo-colonic resection for Crohn’s disease: long-term results. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:462–469.

Scarpa M, Ruffolo C, Polese L, Martin A, D’Incà R, Sturniolo GC, D’Amico DF, Angriman I. Quality of life after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: different questionnaires lead to different interpretations. Arch Surg 2007;142:158–165.

Dunker MS, Stiggelbout AM, van Hogezand RA, Ringers J, Griffioen G, Bemelman WA. Cosmesis and body image after laparoscopic-assisted and open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease. Surg Endosc 1998;12:1334–1340.

Maartense S, Dunker MS, Slors JF, Cuesta MA, Pierik EG, Gouma DJ, Hommes DW, Sprangers MA, Bemelman WA. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open ileocolic resection for Crohn's disease: a randomized trial. Ann Surg 2006;243:143–149.

McLeod RS, Churchill DN, Lock AM. Quality of life of patients with ulcerative colitis preoperatively and postoperatively. Gastroenterology 1991;101:1307–1313.

Guillou PJ, Windsor AJ, Nejim A. The health care economic implications of minimal access gastrointestinal surgery. In Bodger K, Daly MJ, Heatley RV, eds. Clinical economics in gastroenterology, 1st ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd, 2000, pp 133–145.

Scarpa M, Sadocchi L, Ruffolo C, Iacobone M, Filosa T, Prando D, Polese L, Frego M, D'Amico DF, Angriman I. Rod in loop ileostomy: just an insignificant detail for ileostomy-related complications? Langenbecks Arch Surg 2007;392:149–154.

Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Mitchell CM, Zagami E, Applebaum MI. Health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 1989;34:1379–1386.

Blondel-Kucharski F, Chircop C, Marquis P, Cortot A, Baron F, Gendre JP, Colombel JF, Groupe d'Etudes Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires Digestives (GETAID). Health-related quality of life in Crohn’s disease: a prospective study in 231 patients. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:2915–2920.

Fearnhead NS, Chowdhury R, Box B, George BD, Jewell DP, Mortensen NJ. Long-term follow-up of stricturoplasty for Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2006;93:475–482.

Yamamoto T, Fazio VW, Tekkis PP. Safety and efficacy of stricturoplasty for Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 2007;50:1968–1986.

Broering DC, Eisenberger CF, Koch A, Bloechle C, Knoefel WT, Izbicki JR. Quality of life after surgical therapy of small bowel stenosis in Crohn's disease. Dig Surg 2001;18:124–130.

Acknowledgement

We are extremely grateful to Umut Sarpel MD, Bellevue Hospital Center, New York University, NY, USA, for her kind help in the English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Funding: This paper was funded, in part, by the Italian Ministry of the University and Research (MIUR) grant ex 60%.

Preliminary results of this study were presented as a poster at the 50th annual meeting of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (Digestive Disease Week), May 30–June 3, 2009 Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scarpa, M., Ruffolo, C., Bassi, D. et al. Intestinal Surgery for Crohn’s Disease: Predictors of Recovery, Quality of Life, and Costs. J Gastrointest Surg 13, 2128–2135 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-1044-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-1044-y