Abstract

We propose a conceptual model of the key antecedents and outcomes of consumer perceptions of the two components of foreign country image (CI), namely, general country image (GCI) and product country image (PCI), which we meta-analytically tested with input derived from 253 studies included in 176 empirical articles published in the last five decades. Our meta-analysis revealed that both GCI and PCI were positively influenced by foreign brand-, product-, and country-familiarity. Both GCI and PCI were negatively driven by consumer ethnocentrism and animosity, while patriotism generated a negative effect on PCI, but not on GCI. Consumer demographics rarely exhibited a significant association with each of these two image dimensions, with the exception of education that positively affected PCI and income that positively impacted GCI. GCI exhibited a positive effect on PCI perceptions, while both of them had a strong positive impact on evaluation, attitude, and purchase intention associated with foreign products. With a few exceptions, the previous construct associations were moderated by differences between reference and focal countries with regard to their level of economic development, degree of innovativeness, level of industrial performance, and degree of political risk. Finally, study-related time period, focal fieldwork country, and product involvement type exhibited strong control effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As a consequence of the accelerating globalization, growing economic integration, and intensifying trade liberalization of the world’s economies, there has been more than ever an abundance of foreign products and services across local markets (Tintelnot, 2017). This is reflected in the exponential growth of the global value of imports of products and services from US$382.8 billion in 1970 to about US$21.8 trillion in 2020 (World Bank, 2021). This reality has been responsible for conducting a large number of studies during the last five decades, focusing on how country image (CI), that is, the image of a country as a product’s origin, affects foreign consumers’ purchasing behavior (Zeugner-Roth, 2017). Notwithstanding the voluminous and insightful knowledge generated by this line of research, this has been criticized as being largely fragmented, suffering from various inconsistencies, controversies, and sometimes conflicting results (Lu et al., 2016).

In response to these criticisms, there were several attempts in the past to review pertinent research on CI (e.g., Carneiro & Faria, 2016; Lu et al., 2016; Papadopoulos & Heslop, 2002; Roth & Diamantopoulos, 2009; Samiee & Chabowski, 2020) (see Appendix 1 for a summary of the objectives, methodologies, and findings of these review studies). Although these review efforts have helped to organize, integrate, and critically assess previously published material on CI in a systematic and insightful manner, no attempt has yet been made to statistically synthesize and evaluate previous empirical findings using a meta-analytical approach. However, such a meta-analysis of the CI phenomenon would help to consolidate extant knowledge, resolve possible controversies, and guide future research on the subject (Grewal et al., 2018).

To avoid confusion between our meta-analysis on CI and other meta-analyses focusing on country-of-origin (CO) (e.g., De Nisco & Oduro, 2022; Peterson & Jolibert, 1995; Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999), it is important to draw a distinction between these two concepts. While CO refers to the country where the product was made and serves as an extrinsic informational cue for consumer responses (Samiee, 1994; Verlegh & Steenkamp, 1999), CI is a consumer’s summary evaluation of a country as an origin of products and represents a set of characteristics organized into meaningful groups at an overall country or product-country level (Kock et al., 2019; Pappu et al., 2007).Footnote 1 Moreover, while conventional CO studies help to understand whether consumers prefer products from one particular country as opposed to another, CI assessments by consumers allow to analyze why this occurs (Roth & Diamantopoulos, 2009).

Our aim is to fill this need by identifying, synthesizing, and evaluating the key antecedents and outcomes of CI perceptions in the foreign consumer buying decision-making process, based on a meta-analysis of the extant empirical research. Specifically, we have four major goals to accomplish: (a) to develop an integrative conceptual model, incorporating the key independent and dependent variables found in the pertinent literature associated with CI perceptions; (b) to concurrently test the associations between constructs in this model, using structural equation modeling; (c) to examine the moderating role of various macro-level differences between reference and focal countries on these associations; and (d) to investigate possible control effects by study-related temporal, spatial, and product factors.

Our meta-analysis contributes to the international business knowledge in four different ways. First, we synthesize the findings of extant research and propose an integrative model, which stresses the role of CI within the broad consumer decision-making context. The findings of this meta-analysis provide a holistic and cumulative picture of the antecedents and outcomes of CI, which can help to resolve the prevailing ambiguity among academics and practitioners alike as to the role played by certain factors affecting or affected by CI. We expect that the consolidated findings stemming from this meta-analysis, coupled with our recommendations for future research, will provide an inventory of knowledge that will further stimulate scholarly thinking on the subject and help to push this line of research to a more advanced stage of development (Lu et al., 2016).

Second, there are repeated criticisms in the literature (e.g., Samiee, 2010; Usunier, 2006; Usunier & Cestre, 2008) regarding the importance of CI in crafting international business strategies for firms (e.g., selecting a foreign country to establish production facilities) or international trade strategies for countries (e.g., launching a communication campaign to promote locally produced goods abroad). This could be partly ascribed to the existence of inconsistent findings among extant CI studies, which creates a blurred picture as to the exact role of drivers and outcomes of CI (Usunier, 2006). Hence, we expect the findings of our meta-analysis to provide a clearer understanding of the dynamics of the CI phenomenon and allow for a more sound and reliable decision-making at both firm and government levels.

Third, CI research is built on comparisons between a focal country, where the respondents are located, and one or more reference countries, where the product originates from. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that differences between reference and focal countries to account for variations in the effect of factors influencing CI and influenced by it. Our meta-analysis investigates key macro-level country differences with regard to their degree of economic development, innovativeness, industrial performance, and political risk, for which there are indications that they may have a potential moderating role on the drivers and outcomes of CI (Brijs et al., 2011; Knight & Calantone, 2000; Lu et al., 2019). The results of this analysis could provide valuable insights as to the importance of contextual effects in shaping consumer CI perceptions.

Fourth, we take into consideration time- (i.e., study execution period), spatial- (i.e., type of focal country), and product-related (i.e., degree of product involvement) factors to interpret differences in the results produced by extant empirical CI studies. Specifically, we demonstrate that CI perceptions by foreign consumers are sensitive to: (a) the dynamic changes taking place in the international business environment; (b) the developed versus developing/emerging nature of the country where the consumer lives; and (c) the type of product involvement on which they were asked to focus. All these indicate that CI is a complex phenomenon influenced by study-specific factors, and as such there is a need to take these factors into consideration in better grasping foreign consumers’ CI perceptions.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: In the next section, we illustrate the evolution of the CI concept. This is followed by a presentation of the conceptual model and the development of hypotheses. We subsequently explain the methodology undertaken by our study, with a particular focus on the identification, selection, and coding of relevant articles. The next section focuses on data purification and analysis, as well as presents the results with regard to each of the hypotheses set. Then, we discuss our findings, draw conclusions, and offer implications for scholars, managers, and policymakers. The final section highlights the limitations of our meta-analysis and suggests directions for future research.

2 Evolution of the Country Image Concept

As explained earlier, image is a concept very closely associated with CO. In fact, the primary goal of the earliest known CO study was described as testing “…preconceived images of products on the basis of national origin” (Schooler, 1965, p. 394). Later, Nagashima (1970) offered a CO-centric definition of image and asserted “'made in' image is the picture, the reputation, the stereotype that businessmen and consumers attach to products of a specific country” (p. 68). Likewise, Narayana (1981) defines image within the context of “any particular country's product refers to the entire connotative field associated with that country's product offerings” (p. 32). Over time, the image concept has been adapted, refined, and measured to suit particular research goals in numerous investigations, which has served to divide the pertinent literature into three different streams.

The first group of studies focused on customers' overall reactions to products or brands of specific origin (e.g., Gaedeke, 1973; Lillis & Narayana, 1974; Nagashima, 1970, 1977). Studies in this group included antecedents of customer reactions and how people’s images of imported products can affect their purchase intentions. These studies did not take into consideration specific country-related attributes, but view country as serving a ‘halo’ construct. They consider the “made in” label as a sign, the product as an object, and CI as the meaning given by buyers to the “made in label” (Brijs et al., 2011).

Studies comprising the second group identify and measure country-related attributes that form images of countries in the foreign buyer’s mind (Hsieh et al., 2004; Roth & Diamantopoulos, 2009). The goal here is to develop a common basis that people use to judge countries, without, however, referring to product-related attributes (Laroche et al., 2005). This overall image transmitted by a country is referred as General Country Image (GCI), which acts as a powerful extrinsic cue that directs consumers’ positive or negative biases associated with that country’s products and services (Samiee & Chabowski, 2020).

The third group of studies focused on identifying pertinent product-related attributes of countries that are used by customers in assessing products and associated intended choice behavior (e.g., Demirbag et al., 2010; Roth & Romeo, 1992). A more appropriate term associated with this group is Product-Country Image (PCI) (Demirbag et al., 2010; Papadopaulos & Heslop, 1993), which is operationally defined as “the overall perception consumers form of products from a particular country, based on their prior perceptions of the country's production and marketing strengths and weaknesses” (Roth & Romeo, 1992).

3 Integrative Model and Hypotheses

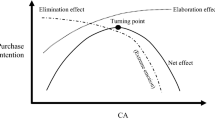

Figure 1 shows the integrative conceptual model of our study, which sets both components of CI, namely, GCI and PCI, as its central constructs. Both GCI and PCI are hypothesized to be predicted by three sets of factors, namely consumer familiarity (i.e., foreign brands, foreign products, foreign countries), consumer ethnographics (i.e., ethnocentrism, patriotism, animosity), and consumer demographics (i.e., gender, age, education, income). GCI is also set as a predictor of PCI, while both GCI and PCI are subsequently hypothesized to affect consumer evaluation of, attitude toward, and intention to buy products originating from a specific foreign country. We also consider differences between reference and focal countries with regard to their level of economic development, degree of innovativeness, level of industrial performance, and degree of political risk as moderators of the various associations between constructs of the model. Finally, we use as control variables the time period that the study was conducted, the nature of the fieldwork country, and the involvement level of the product(s) referred to.

3.1 Consumer Familiarity and CI

Brand familiarity refers to the length of time spent by consumers on processing information about a specific brand (Baker et al., 1986). In fact, it has been postulated that information about brands originating from a specific foreign country represents a knowledge base on a consumer’s memory to form GCI and PCI perceptions (Lopez & Balabanis, 2021). Lopez et al. (2011) argue that corporations are not isolated from the countries where they originate from, thus the familiarity with their brands is linked to their country’s production capabilities. Consumers familiar with a specific foreign brand tend also to be familiar with its country of origin and aware that the brand is imported from abroad (Iversen & Hem, 2011). While the former indicates an increase in consumer understanding and knowledge about the brand’s origin, the latter provides assurance of the commercial success of its country origin and acceptability of its products throughout the world (Heslop et al., 2004; Iversen & Hem, 2011). Brand familiarity also improves the certainty about the brand from a specific foreign country and decreases the costs of information search required to make an assessment about the brand and its origin, thus creating a more favorable GCI and PCI perception by consumers (Laroche et al., 1996). Thus, we can hypothesize that:

H1: Consumer familiarity with a foreign brand positively influences the formation of a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

Product familiarity refers to the number of product-related experiences a consumer has undergone on various occasions (Alba & Hutchinson, 1987). Such experiences may act as a ‘halo’ in building both GCI and PCI (Chan et al., 2010). In this process, consumers attach meanings to a product and incorporate these meanings as heuristic cues to make inferences about its country of origin, thus transferring meanings from product associations into favorable GCI and PCI perceptions (Chan et al., 2010). In fact, consumers may base their GCI and PCI perceptions on salient products they can bring back from memory, especially when they associate countries with certain product categories (Lopez & Balabanis, 2021). Johansson (1989) argues that product familiarity serves as an indicator of the knowledge related to countries that are good manufacturers of a specific product. Consequently, consumers with a high level of product familiarity are expected to have product-specific knowledge about a country that influences their image perceptions (Elliott et al., 2011). In fact, such accumulation of experience with regard to products originating from a foreign country may lead to more objective and less biased GCI and PCI consumer evaluations (Balabanis et al., 2002). In addition, the availability of products from a certain country in retail stores and their international acceptance by consumers may lead buyers to form positive perceptions about products originating from that particular country (Heslop et al., 2004). This leads us to the following hypothesis:

H2: Consumer familiarity with a foreign product positively influences the formation of a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

Country familiarity is defined as an individual’s experience of a country through personal visits, educational knowledge, media exposure, and other means that help to build cognitive associations about a country (Elliott et al., 2011; Kock et al., 2019). Such exposure to a foreign country creates more favorable perceptions by fostering positive feelings as a result of increasing knowledge (hence decreasing psychological distance from the specific country) (Elliott et al., 2011). In particular, direct contact with a foreign country enables consumers to have first-hand knowledge about its characteristics, revise their view of that country under new realities, decrease possible ambiguity and anxiety levels associated with that country, and have a more tolerant attitude toward it (Balabanis et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2019). Consumers who are familiar with a foreign country’s general characteristics (e.g., politics, economy, technology) also tend to reduce their uncertainty about its production capabilities and generate favorable images regarding its products (d’Astous et al., 2008). This is because such characteristics represent national stereotypes, which are expected to be consistent with the assessment of products manufactured in this country, thus creating a favorable GCI and PCI (Chattalas et al., 2008). Hence, we may posit that:

H3: Consumer familiarity with a foreign country positively influences the formation of a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

3.2 Consumer Ethnographics and CI

Consumer ethnocentrism refers to the beliefs of consumers concerning the appropriateness and morality of buying foreign products (Shimp & Sharma, 1987). Ethnocentric consumers view their nation as the “ingroup” and develop negative stereotypes of “outgroups”, that is, nations other than their own (de Nisco et al., 2016). Ethnocentrism will create negative perceptions about foreign countries’ products, because it reflects the superior view held of a consumer’s own country, as opposed to an inferior view held of foreign countries (de Ruyter et al., 1998). Ethnocentric consumers are reluctant to buy foreign-made goods, because they fear to harm their national economy and cause an economic insecurity and/or are proud of supporting their local society both economically and morally (Shimp & Sharma, 1987; Siamagka & Balabanis, 2015). In general, they are negatively predisposed against any product that is not made in their home country and, consistent with their feelings, thoughts, and values to support their own national group, they tend to form unfavorable GCI and PCI perceptions (Brodowski et al., 2004; Kwak et al., 2006). The following hypothesis can therefore be made:

H4: Consumer ethnocentrism negatively influences the formation of a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

Patriotism is defined as deep emotions of attachment and faithfulness to one’s country, without hostility toward other countries (Balabanis et al., 2001). Because patriots love their own country, they are reluctant to buy foreign products, considering it their duty to protect the national economy and indigenous producers (Han, 1988). Since they are also less willing to gather information about other countries, their judgment of foreign countries will be based on stereotypes and even prejudices, rather than accurate information (Balabanis et al., 2001). Consumers high in patriotism feel more similar to and empathize with their compatriot workers threatened by products imported into their home country (Granzin & Olsen, 1998). They are also characterized by a tendency to devote themselves to and make sacrifices for their own country, which may lead to an underestimation of foreign countries’ capabilities to produce reliable, quality goods (Sharma et al., 1995). Hence, patriotic consumers will have more distorted and negatively biased GCI and PCI perceptions associated with imported products (Han, 1988). Therefore, we may posit that:

H5: Consumer patriotism negatively influences the formation of a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

Consumer animosity refers to the remnants of antipathy concerning past or current military, political, social, or economic problems associated with a specific foreign country (Klein et al., 1998). In other words, it is a country-specific emotion, which negatively influences both GCI and PCI consumer perceptions (Chan et al., 2010). Such threats from a foreign country, coupled with unpleasant personal experiences and/or learned/taught conflict information in media and educational institutions, associated with a particular foreign country (or its people), foster a negative attitude and create a feeling of hostility and negativity toward this country and its products (Hoffmann et al., 2011; Nijssen & Douglas, 2004; Stepchenkova et al., 2018). Consumers with a high level of animosity may feel guilty for supporting the economy of an offending country (Nes et al., 2012). They also tend to avoid buying products of the hostile country not because of reasons associated with low quality, but because of their animosity feelings (Fong et al., 2014). Hence, we may hypothesize that:

H6: Consumer animosity negatively influences the formation of a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

3.3 Consumer Demographics and CI

Concerning gender, there are indications that compared to men, female consumers tend to rely more on extensive information when evaluating foreign products (Leonidou et al., 1999) and more correctly define the origin of brands (Balabanis & Diamantopoulos, 2008; Samiee et al., 2005). Several studies (e.g., Chaney & Gamble, 2008; Smith et al., 2010) have also shown that women tend to have more favorable beliefs about foreign market offerings, as well as a higher inclination to buy imported products. For example, Ceballos et al. (2018) showed that women have more favorable attitudes toward shopping from abroad, while Li et al. (2021) reported that products purchased during a foreign country visit can be a means of self-expression for women in their social lives when they go back to their own country. The above argumentations lead to the following hypothesis:

H7: Compared to male consumers, female consumers are more likely to develop a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

With regard to age, older consumers tend to use more information and are more careful when they consider purchasing products from foreign countries compared to their younger counterparts (Leonidou et al., 1999). For example, Chaney and Gamble (2008) ascribed the lower attractiveness of foreign retailers by older consumers to the fact that they are very cautious and conservative in their assessments. On the contrary, younger consumers tend to be more attracted to foreign popular cultures because of greater exposure to mass media (and nowadays social media), more extensive traveling, and higher likelihood to speak foreign languages, and as a result, they are expected to formulate more positive GCI and PCI perceptions (Chaney & Gamble, 2008). As opposed to older consumers, younger people tend to share common needs and wants with their counterparts in other countries and therefore are more receptive to buy foreign made products, especially if these are globally recognized brands (Frank & Watchravesringkan, 2016). Younger people are also less likely to remember any past disputes between their home country and foreign countries, reducing in this way possible bias regarding products originating from these countries (Nakos & Hajidimitriou, 2007). We can therefore hypothesize that:

H8: Compared to older consumers, younger consumers are more likely to develop a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

Concerning education, highly educated consumers tend to be more open-minded, universal, and informative when purchasing imported products, because they are more likely to be exposed to foreign cultures during their studies and/or training (Ahmed & d’Astous, 2008; Sharma et al., 1995). Indeed, there is evidence (e.g., Nijssen & Douglas, 2004) showing that more educated consumers tend to be more favorably predisposed toward foreign countries when making their purchasing decisions and put less emphasis on national-related buying motives, compared to their less educated counterparts (Sharma et al., 1995). They are also in a better position to make more objective evaluations of foreign products based on facts and experiential knowledge, and are less influenced by domestic country bias, thus forming more positive GCI and PCI perceptions (Fernández-Ferrín et al., 2015; Nijssen & Douglas, 2004). Thus, we may posit that:

H9: Compared to consumers with lower education, highly educated consumers are more likely to develop a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

With regard to income, consumers with a higher income tend to have more international experience through extensive traveling, greater affordability to buy foreign goods, and higher accessibility to international media (Nijssen & Douglas, 2004; Samiee et al., 2005). Moreover, high-income consumers have more exposure to foreign living patterns and better awareness of the origin of foreign products/brands, while they can afford the risk in case of purchasing unsatisfactory or problematic products from abroad (Samiee et al., 2005). Furthermore, high-income consumers are more likely to have a positive GCI and PCI perceptions and be less biased against foreign products due to the fact that their world view is less constricted and they are assumed to develop a more cosmopolitan life-style, which is receptive to the idea of buying imported goods (Schaefer, 1997; Sharma et al., 1995). In addition, high-income consumers may view foreign products as a source of prestige due to their rarity and exclusivity and use them as a source of self-expression (Hung et al., 2021). Hence, we can set the following hypothesis:

H10: Compared to consumers with a low income, high-income consumers are more likely to develop a favorable: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

3.4 GCI and PCI Consumer Perceptions

GCI is defined as the totality of descriptive, inferential, and informational beliefs a consumer holds about a specific country (Martin & Eroglu, 1993). This covers a wide range of issues, such as political (e.g., regime and market system status), economic (e.g., living standards and welfare system), technological (e.g., level of research and development), and social (e.g., individual rights and freedoms) characteristics of a foreign country (Martin & Eroglu, 1993; Pappu et al., 2007; Parameswaran & Pisharodi, 2002). These perceptions at the GCI level inevitably influence consumers’ images of a particular foreign country’s products, because they represent beliefs with regard to this country’s ability to produce advanced, safe, reliable, and high-quality products (Heslop et al., 2008). Indeed, several studies (e.g., Li et al., 2014) have shown that a country’s political stability, living standards, industrialization level, and technological advancement serve as a summary attribute to form positive PCI perceptions with regard to products from that country. This leads to the development of the following hypothesis:

H11: The existence of favorable GCI perceptions by consumers leads to favorable PCI perceptions.

3.5 CI Perceptions and Consumer-Related Outcomes

Both GCI and PCI consumer perceptions may serve as a ‘halo’ construct in the foreign product evaluation process, which is defined as the assessment of a country with respect to a specific product (Häubl, 1996). More specifically, consumers infer product quality from these image perceptions, because they may not be able to accurately assess the product’s attributes in the absence of sufficient knowledge (Han, 1989). As such, a country name acts as a categorical cue for information processing, with products receiving positive evaluations, when they have a favorable GCI and PCI (Lee & Ganesh, 1999). In particular, if the competences of a country represent important benefits associated with a specific product, this usually results in a favorable matching between the consumer image perceptions and the product in question (Roth & Romeo, 1992). A favorable GCI and PCI also stimulates consumers’ interest in products from the specific foreign country and leads them to devote more attention to product information and its evaluative inferences (Hong & Wyer, 1989). It will also push consumers to generalize product information from a specific country over brands originating from this country and use them for their favorable evaluation (Han, 1989, 2016). Based on the above, we may hypothesize that:

H12: Consumer evaluations of foreign products are positively influenced by favorable perceptions of: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

An attitude toward a product refers to the strength of various salient beliefs by the consumer that a product has certain attributes, as well as how these attributes are assessed (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). Such attitude toward a product is the outcome of objective (e.g., product usage) and/or subjective (e.g., word-of-mouth) assessments with regard to country characteristics, as well as, to technical, workmanship, economy, service, and other issues relating to this product (Knight & Calantone, 2000). All these represent evaluative responses, the summation of which leads to the formation of attitudes through a mediating process (Solomon, 2020). Indeed, the set of beliefs about the country’s characteristics convert to impressions about products originating from this country and influence inferences about the latter’s properties (Halkias et al., 2016). Fishbein’s model also implies that the higher the extent to which a country’s products are perceived to possess attributes important to consumers, the more favorable their attitude toward these products (Cohen et al., 1972). Hence, both GCI and PCI act as stereotypes associated with products from a particular country, which subsequently serve as important cues for attitude formation (Lee, 2020). Therefore, we may hypothesize that:

H13: Consumer attitudes toward foreign products are positively influenced by favorable perceptions of: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

Intention to buy refers to the willingness of a consumer to purchase a product (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). Notably, the theory of Reasoned Action suggests that attitude toward an object, action, or event is a predictor of intentions to perform a particular behavior, while intentions are viewed as the best predictor of performing that particular behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980). The existence of favorable GCI and PCI serves as an indicator of value and trustworthiness of a product originating from a particular country, which can increase consumer desirability toward it (Matarazzo et al., 2020). General beliefs toward products from a specific foreign country denote product-related attributes with a potential effect on the willingness to buy foreign products, since these can facilitate consumers to overcome the difficulty of evaluating them (Suh & Kwon, 2002). In addition, having a favorable GCI and PCI can help to reduce uncertainty associated with foreign products and enhance in this way their value potential (Souiden et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). Accordingly, the overall favorable assessment of a country and its products is expected to translate into an intention to buy products originating from this country (Javalgi et al., 2013). Thus, we may posit that:

H14: Consumer intentions to purchase foreign products are positively influenced by favorable perceptions of: (a) GCI; and (b) PCI.

3.6 Macro-level Country Differences as Moderators

A country’s level of economic development is “the process of creating wealth through the mobilization of human, financial, physical, and natural resources to generate marketable goods and services for improving standards of living and quality of life in an area” (Pittman & Phillips, 2014, p. 1791). Batra et al. (2000) noted that developing country-based consumers have a high level of admiration of economically developed country way of living and have more favorable attitudes toward brands from these countries. There are also indications that consumers in underdeveloped/emerging markets have more positive responses toward products from developed countries, mainly because they symbolize a wealthy lifestyle, act as an indicator of social status, and address a desire to be part of the global community (Batra et al., 2000; Sharma, 2011). In contrast, consumers tend to associate products from countries at lower levels of economic development with low quality materials and poor design (Cordell, 1992). Accordingly, we can hypothesize the following:

H15: When the level of economic development of the reference country is higher than that of the focal country: (a) the positive influence of consumer familiarity constructs on GCI and PCI becomes stronger; (b) the negative effect of consumer ethnographics on GCI and PCI becomes weaker; (c) the positive impact of consumer demographics on GCI and PCI becomes stronger; (d) the positive influence of GCI on PCI becomes stronger; and (e) the positive impact of GCI and PCI on outcome variables becomes stronger.

Country innovativeness denotes a country’s potential to produce a steady stream of commercially relevant innovations, as well as the achievements derived from the development and execution of innovation activities (Porter & Stern, 2001; Robertson et al., 2022). Country innovativeness is a particularly important factor shaping country image perceptions in the case of technology-related products (especially by consumers living in less innovative countries), because this is associated with product reliability, creativity, and superior quality (Shaffer et al., 2016). In highly innovative countries, firms tend to heavily engage in research and development activities to introduce new products, which helps them to enjoy high levels of reputation in international markets (Furman et al., 2002). They also enjoy several advantages, such as easy access to human (e.g., well-educated employees), financial (e.g., low-cost venture capital), and technological (e.g., advanced information technologies) resources that provide fertile ground for promoting their innovative activities (Faber & Hesen, 2004). In fact, these countries owe their comparative advantage in international trade to the supporting role of local institutions that facilitate, encourage, and even enforce innovation among indigenous firms (Cuervo-Cazurra & Ramamurti, 2017). Exporting research (e.g., Edeh et al., 2020) acknowledges the positive impact of product innovativeness on the firm’s export performance due to its facilitating role in creating higher customer value. This is in harmony with recent findings in importing research (e.g., Leonidou et al., 2022), indicating that importers tend to search for foreign sources of supply that would provide them with novel products securing a successful acceptance by buyers in their markets. The previous argumentation leads us to the following hypothesis:

H16: When the level of innovativeness of the reference country is higher than that of the focal country: (a) the positive influence of consumer familiarity constructs on GCI and PCI becomes stronger; (b) the negative effect of consumer ethnographics on GCI and PCI becomes weaker; (c) the positive impact of consumer demographics on GCI and PCI becomes stronger; (d) the positive influence of GCI on PCI becomes stronger; and (e) the positive impact of GCI and PCI on outcome variables becomes stronger.

Industrial performance refers to a country’s ability to produce and export manufactured goods competitively (Zhang, 2010). Countries high in industrial performance produce and export value-added products, maintain a higher share of high technology-related activities, and have a significant impact on world trade (Halkos et al., 2021). These countries are also characterized by superior welfare due to wider product variety, better product quality, and heightened domestic price competition (Ara, 2020), while at the same time are in a position to produce and sell their products abroad at affordable prices (Hill & Hult, 2019). Scoring high on industrial performance also implies a country with high levels of competence in producing products that can fulfil promises to foreign consumers and communicate trust (Barbarossa, 2018). All these are responsible for generating high customer value, as well as positive feelings by foreign buyers about the country and its products (Halkias et al., 2016). Hence, we may hypothesize that:

H17: When the level of industrial performance of the reference country is higher than that of the focal country: (a) the positive influence of consumer familiarity constructs on GCI and PCI becomes stronger; (b) the negative effect of consumer ethnographics on GCI and PCI becomes weaker; (c) the positive impact of consumer demographics on GCI and PCI becomes stronger; (d) the positive influence of GCI on PCI becomes stronger; and (e) the positive impact of GCI and PCI on outcome variables becomes stronger.

Political risk refers to the level of governmental stability, institutional/regulatory quality, and sound applicability/enforcement of legislation prevailing in a country (Tang & Buckley, 2020), which influences the cost and risk of international trade operations (Zheng et al., 2017). Consumers are usually reluctant to purchase products from politically risky countries, as this involves supply vulnerability due to incidents like government failures, terrorist attacks, and war conditions, which can limit product availability because of disruptions in production and logistics activities (Gupta, 2008). It is also likely that problems in politically risky countries associated with various unfavorable incidents (e.g., wars, riots, unrests) to have greater exposure in mainstream and social media, which can create negative perceptions and have harmful effects on the purchasing decisions of consumers in other countries (Crouch et al., 2021). Political risk also indicates a possibility for political figures to set and implement rules and regulations for their own interest at the expense of the private sector, resulting in poorer business performance and lower product attractiveness (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2018). In relation to this, empirical evidence shows that firms located in politically risky countries are not sufficiently prepared for accommodating the demands of the dynamic international market, which is responsible for creating a distorted image for their products in foreign countries (Hernández et al., 2022). The following hypothesis can therefore be made:

H18: When the level of political risk of the reference country is lower than that of the focal country: (a) the positive influence of consumer familiarity constructs on GCI and PCI becomes stronger; (b) the negative effect of consumer ethnographics on GCI and PCI becomes weaker; (c) the positive impact of consumer demographics on GCI and PCI becomes stronger; (d) the positive influence of GCI on PCI becomes stronger; and (e) the positive impact of GCI and PCI on outcome variables becomes stronger.

4 Research Method

Our meta-analysis covered articles published since the inception of this body of research up to the end of 2020. To identify relevant articles, we used various electronic databases, namely Scopus, Web of Science, EBSCO, JSTOR, and ABI/INFORM. This was supported by searches in the databases of individual academic publishers, such as ScienceDirect, Emerald, Sage, Springer, Taylor and Francis, and Wiley. We searched these databases using the following keywords: “country image”, “product-country image”, “general country image”, “product judgment”, “foreign product/brand”, “imported product”, and “country-of-origin”. We also manually reviewed the tables of contents of relevant journals, as well as the reference sections of pertinent articles focusing on CI in general, and GCI and PCI in particular.

For a study to be included in our meta-analysis, it had to fulfill the following eligibility criteria: (a) to have the form of an academic article appeared in a marketing, management, or other business journal of an international standing published in English, thus excluding research notes, chapters, and conference proceedings; (b) to examine CI (GCI and/or PCI) of a specified foreign country from a consumer’s perspective, as opposed to that of business/industrial buyers; (c) to have an empirical (rather than conceptual or methodological) nature, providing relevant information (e.g., study execution year, name of focal/reference country, sample characteristics) on the research method adopted; (d) to focus on antecedents and/or outcomes of CI (GCI and/or PCI); and (e) to adequately report relevant statistics, such as correlation coefficients, beta values, t-values, or p-values, that are essential for performing a meta-analysis.

All eligible articles were content-analyzed to identify the strength, sign, and direction of associations between constructs predicting or predicted by GCI and PCI perceptions. This helped to extract a nomological network of constructs acting as antecedents or outcomes of GCI and PCI, as well as develop hypotheses regarding associations between constructs. As the testing of the conceptual model requires information about effect sizes between each pair of variables included in the conceptual model (Grewal et al., 2018), the focus of our study was on the most commonly examined antecedents and consequences of GCI and PCI. The end-result was to reduce the number of pertinent studies from where relevant data could be extracted down to 253, which were found in 176 articles and published in 59 journals. Appendix 2 shows the specific steps taken to identify studies eligible for the purpose of our meta-analysis.

To code the articles selected, we used two experienced researchers who, prior to the full-scale coding, underwent rigorous training and coded tentatively several articles. In order to safeguard the completeness, accuracy, and standardization of the coding process, a coding template was developed, accompanied by a special coding manual, which explained the nature of each construct used in the integrative model, together with the key information required to be extracted from the various articles (Grewal et al., 2018). Using the prescribed procedures, the two coders worked independently to record the relevant data extracted from each article, under the close guidance and supervision of an expert in the field.

Specifically, the coders separately entered in a spreadsheet the sign, strength, and significance of the effect(s) of: (a) GCI on PCI; (b) antecedent factors on GCI and PCI; and (c) GCI and PCI on outcome variables. For each effect, the study sample size together with the Cronbach's alpha values of the constructs employed was recorded. With the completion of the coding procedure, the data sets generated by the two coders were compared and contrasted to identify any differences, resulting in satisfactory inter-coder reliability scores, ranging from 0.85 to 1. In the case of inconsistencies, these were carefully discussed between the supervisor and the two coders to reach a commonly agreed code to be used for statistical analysis purposes.

All moderating variables were measured on a categorical basis (where 0 = lower and 1 = higher), where the reference country was compared to the focal country using data derived from the specific year that the empirical study was conducted. The level of economic development was measured in terms of GDP per capita, with the relevant information extracted from the World Bank. For country innovativeness degree, we used the Global Innovation Index prepared by the World Intellectual Property Organization, which comprises a set of indicators referring to institutions, human capital and research, infrastructure, market sophistication, business sophistication, knowledge and technology outputs, and creative outputs. The level of industrial performance was measured using the industrial performance score provided by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization’s Competitive Industrial Performance Index, which includes indicators referring to a country’s capacity to produce and export manufactured goods, its technological deepening and upgrading, and its world impact with regard to manufacturing and exporting. The degree of political risk was based on an index extracted from the Euromoney Country Risk, which takes into consideration issues like corruption, government non-payments, government stability, information access/transparency, institutional risk, and regulatory and policy environment. Finally, for the three control variables used in our meta-analysis, study execution time was divided into studies executed before 2010 (0) and those conducted from 2010 onwards (1), study fieldwork country that distinguishes between studies that took place in a developing/emerging country (0) and those executed in a developed country (1), and study product focus that refers to whether the study examined products of low involvement (0) or high involvement (1).

5 Data Purification, Analysis, and Results

To test our integrative conceptual model, studies included in our meta-analysis had to provide information about the correlation coefficient (r) or any other statistic that could be converted to r, such as beta values, t-values, and p-values. It was also important to provide the sample size and the Cronbach’s alpha for the constructs employed in order to adjust for measurement error in multi-item scales used in the studies selected to be analyzed (Grewal et al., 2018).

To exclude the possibility of publication bias, we have followed the recommendations by Borenstein et al. (2009): first, we tried to get a sense of the available data, indicating that the mechanism of publication bias based on statistical significance was not powerful in our meta-analysis; second, we checked for evidence of bias by using the funnel plot method in association with Egger’s test, whereby the rank correlation test did not yield a significant p-value; and third, using Rosenthal’s fail-safe N test, we examined whether the observed associations between constructs were entirely artifacts of bias, which suggested that there was a need for substantially too many studies, before turning the cumulative effect for each of these associations into non-significant.

Meta-analytical correlations using the incomplete data method was used, as this allows the coverage of studies that contain at least one pair-wise correlation between the constructs under investigation (Colquitt et al., 2000). Following Hunter and Schmidt (2004), the homogeneity between the study error and sample error was tested. A random-effects model was used to calculate mean correlation, as it makes it possible to account for variation of the population parameter (ρ) across studies (Raudenbush, 2009). Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of our meta-analysis, namely, total number of studies per construct association, sign pattern of construct association, cumulative sample size per association, the computed weighted mean correlations (r), correlations corrected for attenuating artifacts (cr), confidence intervals (at 95% level), z-values (using the Fisher’s r to z transformation), and the Q statistic to assess the difference between factor levels on explaining the effect heterogeneity.

5.1 Results for Main Paths Analysis

Table 2 shows the results of the meta-SEM analysis conducted, with the model proposed having an acceptable fit with the data, as indicated by the fit indices obtained (CFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.14, SRMR = 0.07). The R2 for GCI was 49.8%, for PCI was 81.4%, for foreign product evaluation was 24.2%, for attitude toward foreign products was 27.2%, and for intention to buy foreign products was 38.4%, which indicate a satisfactory explanation of all key dependent variables by their hypothesized independent variables. Standardized path coefficients and corresponding z-values for each of the hypothesized paths of the conceptual model indicate that, with a few exceptions, these were statistically significant and with the correct sign.

With regard to consumer familiarity variables, foreign brand familiarity was found to have a positive influence on both consumer GCI perceptions (β = 0.600, z = 19.521, p = 0.000) and PCI perceptions (β = 0.528, z = 18.347, p = 0.000), which confirm H1a and H1b respectively. Hypotheses H2a and H2b are also validated, because foreign product familiarity exhibited a positive effect on both GCI (β = 0.562, z = 18.928, p = 0.000) and PCI (β = 0.485, z = 17.470, p = 0.000). Foreign country familiarity was also revealed to positively influence GCI (β = 0.579, z = 17.675, p = 0.000) and PCI (β = 0.630, z = 18.563, p = 0.000), thus providing support for H3a and H3b respectively.

Concerning consumer ethnographic characteristics, our results confirm the hypothesized negative influence of consumer ethnocentrism on both GCI (β = − 0.191, z = − 8.704, p = 0.000) (i.e., H4a) and PCI (β = − 0.293, z = − 12.283, p = 0.000) (i.e., H4b). Consumer patriotism did not have a statistically significant effect on GCI perceptions (β = − 0.004, z = − 0.202, p = 0.840) (thus rejecting H5a), but, as hypothesized in H5b, negatively affected PCI perceptions (β = − 0.325, z = − 13.336, p = 0.000). As hypothesized in H6a and H6b, consumer animosity was found to negatively impact GCI (β = − 0.279, z = − 9.086, p = 0.000) and PCI (β = − 0.280, z = − 8.804, p = 0.000).

With regard to consumer demographics, both H7a and H7b are rejected because gender was not found to be a statistically significant predictor of either GCI (β = 0.018, z = 0.602, p = 0.547) or PCI (β = 0.034, z = 1.117, p = 0.264). Although age exhibited a significant impact on GCI (β = − 0.101, z = − 3.445, p = 0.001), this was not positive as expected, while there was no significant effect of age on PCI (β = − 0.027, z = − 0.902, p = 0.367), providing no support for both H8a and H8b. H9a, which links education with GCI, is rejected (β = 0.025, z = 1.196, p = 0.232), while there was a significant effect of education on PCI (β = 0.053, z = 2.461, p = 0.014), thus confirming H9b. While H10a is supported, as income level significantly influences GCI perceptions (β = 0.065, z = 3.080, p = 0.002), the opposite was true with regard to H10b, because the impact of income on PCI was not found to be significant (β = 0.014, z = 0.670, p = 0.503).

Our results revealed a significant positive influence of consumer perceptions of GCI on PCI (β = 0.788, z = 7.466, p = 0.000), which confirms H11. With regard to consumer responses, foreign product evaluation was found to be positively predicted by both GCI (β = 0.529, z = 19.529, p = 0.000) and PCI (β = 0.582, z = 21.532, p = 0.000), lending support to H12a and H12b respectively. H13a and H13b are also validated because both GCI (β = 0.726, z = 23.945, p = 0.000) and PCI (β = 0.633, z = 22.785, p = 0.000) exhibited a significant positive effect on consumer attitudes toward foreign goods. Finally, H14a and H14b are confirmed, as intention to buy foreign products was positively affected by both GCI (β = 0.790, z = 25.082, p = 0.000) and PCI (β = 0.746, z = 25.170, p = 0.000).

5.2 Results of Moderation Analysis

We performed the moderation analysis by using categorical moderators of the effect size for each main hypothesized path in a random effects model, based on the Hunter-Schmidt estimator and using the standard procedural remedies for moderation analysis (Cheung & Chan, 2004). We considered group comparisons using four variables describing macro-level differences between reference and focal countries reported in the studies included in our meta-analysis, namely country economic development, innovativeness, industrial performance, and political risk. For each of these moderators, a mean group comparison was performed by testing the null hypothesis of whether the difference of the mean effect was different than zero between the two groups. This was done by introducing each categorical variable of the study characteristic in the estimation of the random effects model. Given that our effects have already been standardized using Fischer's r to z transformation, this allowed us to compare all studies in the path of interest for differences between their mean effect size for each of the four moderator variables. It was assumed that both groups share the same degree of variance to make the comparison meaningful and that an adequate number of studies were present in both groups. For those relationships, which did not have enough studies within each group, no moderation analysis was performed. Cochran's Q statistic was used to evaluate the heterogeneity of the mean effect size between the groups. For all hypothesized paths, the model-level heterogeneity and the covariate level heterogeneity were evaluated and reported alongside the change in the effect (β) of the one group versus the baseline group.

With regard to moderation effects due to country differences in economic development, out of 27 associations between constructs of the model, ten could not be tested because of lack of sufficient data to run the analysis (see Table 3). Of the remaining 17 associations, the results show that when the reference country is more economically developed than the focal country, there is a strengthening of the relationship between product familiarity and PCI (b = 0.011, Q = 17.727, p = 0.000), education and GCI (b = 0.057, Q = 10.927, p = 0.004), education and PCI (b = 0.048, Q = 25.891, p = 0.000), GCI and PCI (b = 0.579, Q = 143.845, p = 0.000), GCI and evaluation (b = 0.301, Q = 20.536, p = 0.000), PCI and evaluation (b = 0.727, Q = 94.129, p = 0.000), GCI and attitude (b = 0.382, Q = 33.414, p = 0.000), PCI and attitude (b = 0.206, Q = 24.908, p = 0.000), GCI and intention (b = 0.331, Q = 34.572, p = 0.000), and PCI and intention (b = 0.298, Q = 58.118, p = 0.000). On the other hand, this factor was found to weaken the association between ethnocentrism and PCI (b = − 0.260, Q = 66.010, p = 0.000), animosity and PCI (b = − 0.195, Q = 62.114, p = 0.000), and income and PCI (b = − 0.083, Q = 30.896, p = 0.000). Regardless of the relative positions of the focal and reference countries, there was no moderating effect of gender on GCI (b = − 0.047, Q = 4.421, p = 0.110) and gender on PCI (b = − 0.070, Q = 1.617, p = 0.446).

Data unavailability did not allow to test 13 associations for the moderating impact of differences in innovativeness between reference country and focal country. With regard to the remaining 14 associations, when the reference country innovativeness score was higher than that of the focal country, the links connecting product familiarity to PCI (b = 0.038, Q = 11.984, p = 0.002), education to PCI (b = 0.030, Q = 37.139, p = 0.000), GCI to PCI (b = 0.599, Q = 134.886, p = 0.000), GCI to evaluation (b = 0.310, Q = 20.588, p = 0.000), PCI to evaluation (b = 0.776, Q = 204.622, p = 0.000), GCI to attitude (b = 0.415, Q = 34.601, p = 0.000), PCI to attitude (b = 0.215, Q = 27.464, p = 0.000), GCI to intention (b = 0.398, Q = 38.253, p = 0.000), and PCI to intention (b = 0.300, Q = 57.348, p = 0.000) become stronger. However, under the same condition, the effects of ethnocentrism on PCI (b = − 0.247, Q = 67.087, p = 0.000), animosity on PCI (b = − 0.181, Q = 61.411, p = 0.000), and income on PCI (b = − 0.087; Q = 25.128, p = 0.000) become weaker. Only on the relationship between gender and PCI, country innovativeness differences did not produce a significant moderation effect (b = 0.008; Q = 0.666, p = 0.717).

Only 15 out of 27 construct associations could be tested for the moderating effect of industrial performance differences between reference and focal countries. Our results indicate that when the reference country score with regard to industrial performance is higher than that of focal country, the effect of product familiarity on PCI (b = 0.035, Q = 12.095, p = 0.002), GCI on PCI (b = 0.324, Q = 118.39, p = 0.000), GCI on evaluation (b = 0.257, Q = 18.036, p = 0.000), PCI on evaluation (b = 0.455, Q = 53.596, p = 0.000), GCI on attitude (b = 0.633, Q = 81.796, p = 0.000), PCI on attitude (b = 0.372, Q = 4.417, p = 0.011), GCI on intention (b = 0.312; Q = 41.344, p = 0.000), and PCI on intention (b = 0.402, Q = 66.330, p = 0.000) are amplified. On the other hand, the impact of ethnocentrism on PCI (b = − 0.199, Q = 61.112, p = 0.000), animosity on PCI (b = − 0.167, Q = 59.416, p = 0.000), education on PCI (b = − 0.047; Q = 80.543, p = 0.000) and income on PCI (b = − 0.078; Q = 8.219, p = 0.016) are attenuated. Contrary to our hypothesis, industrial performance superiority of the reference country negatively moderated the influence of education on PCI (b = − 0.047, Q = 80.543, p = 0.000), while no moderation effect was found on the association between gender and PCI (b = 0.051; Q = 3.298, p = 0.192).

Finally, with regard to the moderating role of country differences concerning political risk, only 17 out of the total 27 construct associations had sufficient data for analysis. Specifically, when the reference country is politically less risky than the focal country, the positive effect of product familiarity on PCI (b = 0.037, Q = 12.189, p = 0.002), education on GCI (b = 0.057; Q = 10.927, p = 0.004), education on PCI (b = 0.039, Q = 40.335, p = 0.000), GCI on PCI (b = 0.589, Q = 143.283, p = 0.000), GCI on evaluation (b = 0.287, Q = 19.756, p = 0.000), PCI on evaluation (b = 0.753, Q = 134.711, p = 0.000), GCI on attitude (b = 0.382, Q = 33.414, p = 0.000), PCI on attitude (b = 0.201, Q = 26.193, p = 0.000), GCI on intention (b = 0.340, Q = 36.300, p = 0.000), and PCI on intention (b = 0.342, Q = 60.721, p = 0.000) were more pronounced. Under the same condition, the effect of ethnocentrism on PCI (b = − 0.236, Q = 64.506, p = 0.000), animosity on PCI (b = − 0.202, Q = 68.908, p = 0.000), and income on PCI (b = − 0.087; Q = 44.695, p = 0.000) were de-escalated. However, we were not able to confirm the moderating effect of political risk differences on the link between gender and GCI (b = − 0.047; Q = 4.421, p = 0.11) and between gender and PCI (b = 0.008; Q = 0.666, p = 0.717).

5.3 Results of Control Effects

With regard to control effects, we considered group comparisons using three study characteristics: time period of study execution (≥ 2010 versus < 2010), focal country (developing/emerging versus developed), and product type (i.e., low-involvement versus high-involvement).

Based on data availability, we were able to test the control effect of the study execution time for only 22 of 27 associations. Accordingly, compared to studies conducted before 2010, those executed in 2010 and onwards exhibited stronger effects between: product familiarity and GCI (b = 0.262, Q = 137.219, p = 0.001), product familiarity and PCI (b = 0.203, Q = 12.584, p = 0.013), education and PCI (b = 0.091, Q = 27.814, p = 0.000), GCI and PCI (b = 0.079, Q = 385.605, p = 0.000), GCI and evaluation (b = 0.035, Q = 58.035, p = 0.000), PCI and evaluation (b = 0.592, Q = 273.326, p = 0.000), GCI and attitude (b = 0.354, Q = 135.856, p = 0.000), PCI and attitude (b = 0.014, Q = 117.267, p = 0.001), GCI and intention (b = 0.137, Q = 204.497, p = 0.000), and PCI and intention (b = 0.801, Q = 314.584, p = 0.000) (see Table 4). On the other hand, the effects of ethnocentrism on GCI (b = − 0.040, Q = 52.285, p = 0.000), ethnocentrism on PCI (b = − 0.424, Q = 216.648, p = 0.000), patriotism on PCI (b = − 0.805, Q = 388.713, p = 0.000), and animosity on PCI (b = − 0.255, Q = 154.927, p = 0.000) became weaker for the studies published from 2010 onwards. Surprisingly, links connecting brand familiarity to PCI (b = − 0.001, Q = 67.711, p = 0.001) and consumer education to PCI (b = − 0.057, Q = 10.927, p = 0.004) became weaker in studies that were published in 2010 and later. No significant control effect was found between brand familiarity and GCI (b = 0.068, Q = 2.547, p = 0.280), gender and GCI (b = − 0.030, Q = 4.421, p = 0.110), gender and PCI (b = − 0.070, Q = 3.696, p = 0.449), and income and PCI (b = 0.002, Q = 0.395, p = 0.999).

We analyzed the control effect of the study focal country on 19 out of the total 27 construct associations. Our results revealed that in case of studies performed in developed countries compared to developing ones, the links connecting product familiarity to GCI (b = 0.419, Q = 15.068, p = 0.001), product familiarity to PCI (b = 0.149, Q = 13.790, p = 0.003), education to PCI (b = 0.122, Q = 28.653, p = 0.000), income to PCI (b = 0.116; Q = 32.444, p = 0.000), GCI to PCI (b = 0.352, Q = 132.939, p = 0.000), GCI to evaluation (b = 0.425, Q = 25.239, p = 0.000), PCI to evaluation (b = 0.212, Q = 181.646, p = 0.000), GCI to attitude (b = 0.331, Q = 34.795, p = 0.000), GCI to intention (b = 0.353, Q = 53.851, p = 0.000), and PCI to intention (b = 0.301, Q = 49.208, p = 0.000) became stronger. We also discovered weakening effects in this group of studies on the relationships between: ethnocentrism and PCI (b = − 0.177, Q = 53.02, p = 0.000), patriotism and PCI (b = − 0.805, Q = 388.713, p = 0.000), and animosity and PCI (b = − 0.123, Q = 70.57, p = 0.000). Focal country type did not exhibit a control effect on the links between brand familiarity and GCI (b = 0.184, Q = 2.547, p = 0.28), brand familiarity and PCI (b = − 0.029, Q = 0.659, p = 0.719), ethnocentrism and GCI (b = − 0.019, Q = 2.168, p = 0.338), gender and PCI (b = − 0.020, Q = 0.149, p = 0.928), and PCI and attitude (b = 0.381, Q = 4.247, p = 0.120).

The control effect of study product focus could be tested on 21 out of the total 27 construct associations. In studies where the focal product was of high-involvement, there was a strengthening of the relationships between: brand familiarity and GCI (b = 0.287, Q = 56.476, p = 0.001), product familiarity and GCI (b = 0.223, Q = 8.903, p = 0.012), product familiarity and PCI (b = 0.097, Q = 8.608, p = 0.014), education and GCI (b = 0.053; Q = 11.096, p = 0.004), GCI and PCI (b = 0.400, Q = 113.842, p = 0.000), GCI and evaluation (b = 0.379, Q = 27.229, p = 0.000), PCI and evaluation (b = 0.309, Q = 39.45, p = 0.000), GCI and attitude (b = 0.42, Q = 34.795, p = 0.000), PCI and attitude (b = 0.733, Q = 23.206, p = 0.000), GCI and intention (b = 0.338, Q = 42.209, p = 0.000) and PCI and intention (b = 0.353, Q = 49.553, p = 0.000). Under the same condition, though, the link between ethnocentrism and PCI (b = − 0.183, Q = 48.751, p = 0.000), patriotism and PCI (b = − 0.609, Q = 7.126, p = 0.028), gender and GCI (b = − 0.054, Q = 9.987, p = 0.007), and education and PCI (b = − 0.026, Q = 24.134, p = 0.000) became weaker. Study product focus did not have any effect on the association between brand familiarity and PCI (b = 0.149, Q = 4.168, p = 0.124), gender and PCI (b = 0.025, Q = 3.503, p = 0.174), and income and PCI (b = 0.030, Q = 0.174, p = 0.916).

6 Discussion

Our study offers an integrative picture of the most frequently examined antecedents and outcomes of CI consumer perceptions over the last five decades. The meta-analysis undertaken has synthesized extant knowledge on the subject, confirming that: (a) both GCI and PCI are positively influenced by foreign brand-, product-, and country-familiarity; (b) consumer ethnocentrism and animosity are responsible for creating unfavorable GCI and PCI perceptions, while patriotism has a detrimental effect on PCI (but not on GCI); (c) consumer demographics rarely act as predictors of CI dimensions, with the exception of education having a positive influence on PCI and income having a positive impact on GCI; (d) GCI is conducive toward developing PCI perceptions; and (e) both GCI and PCI have a positive impact on consumer evaluation, attitude, and purchase intention with regard to foreign products.

The strong influence of familiarity constructs on both GCI and PCI stresses the importance of positive knowledge regarding foreign countries, products, and brands in generating a favorable image for countries and products originating from them. This implies that knowledge gained by consumers through a well-representation of products and brands by firms from a foreign country spills over to positive impressions about it and its products, that in turn contribute to the desirability of products and brands from that particular country. This finding highlights the crucial role of disseminating favorable information related to a country and its products that can reach consumers located in foreign markets through various sources.

The finding that consumer ethnocentrism and animosity negatively influence both GCI and PCI shows that consumer dispositions to support the home market and/or dislike foreign countries play a crucial role in shaping the image of products from foreign countries. That patriotism has a negative influence on PCI but not on GCI implies that this variable may not be influential on the impressions about general country characteristics but its effect may be activated when assessing products from a foreign country as these products may risk the success potential of domestic firms.

The fact that gender and age were not confirmed as predictors of GCI and PCI may be attributed to the relatively limited availability of data and/or data without a clear dominant pattern in the studies included in our meta-analysis. Concerning education, this positively influenced only PCI, confirming the tendency of highly educated consumers to hold less biased views of products of foreign countries (Nijssen & Douglas, 2004). The positive effect of income level on GCI could be attributed to a higher likelihood of more affluent consumers to have visited foreign countries and/or possessed/consumed their products, resulting in a less biased, first-hand information.

The finding that both GCI and PCI were conducive to all tested components of consumer decision-making process, confirms their positive role as an input to evaluation, attitude development, and formation of purchase intention for foreign products/brands. This is a crucial finding because all these outcome variables (i.e., evaluation, attitude, purchase intention) are critical prerequisites for making the consumer to proceed with the actual purchase/ownership, which marks the beginning of his/her relationship with a particular foreign product/brand.

The moderation analysis undertaken shows that differences between reference and focal countries set the boundary conditions for the relationships among constructs in the conceptual model. Specifically, whenever the reference country is superior to the focal country in terms of economic development, innovativeness, industrial performance, and political risk, the impact of familiarity variables on GCI and PCI becomes stronger, the effect of ethnographic variables on GCI and PCI becomes weaker, and the impact of these CI dimensions on consumer reactions to foreign products is amplified. This demonstrates that the macro-level differences between reference and focal countries play a pivotal role in explaining variations in the results regarding antecedents and outcomes of CI perceptions by consumers.

Finally, the control analysis performed reveals the study characteristics-dependent nature of the CI research. The growing effect of the study execution year can be explained by the intensifying globalization over the last decades, which has steadily increased people’s exposure to foreign countries and their offerings, thus making them more receptive to their products. The stronger effects in the case of studies conducted in developed countries can be ascribed to their greater receptiveness to foreign products due to their higher living standards, more advanced infrastructures, and better socio-economic conditions. The product involvement effect can also be justified by their higher prices, greater consumption risks, and stronger peer pressure associated with high-involvement products, which lead consumers to actively learn about their countries of production.

7 Implications

7.1 Implications for Scholars

Our study has provided an integrative conceptual model of the mechanism linking GCI and PCI perceptions to their antecedents and outcomes, thus helping to gain an all-encompassing view of the subject. Since recent studies involve many other variables, there is definitely more research to be done to have a more complete picture of the CI phenomenon. For example, the antecedent side of our model could be enriched with cultural factors (e.g., religious beliefs), positive consumer dispositions (e.g., cosmopolitanism), and consumer personality (e.g., extroversion), while the outcome side could be extended to incorporate actual purchase behavior, post-purchase evaluation, and repeat purchase (or loyalty). In addition, the great variability of definitions, operationalizations, and measurements of various constructs associated with CI research necessitates the development of uniform scales to allow comparability of results across different studies and countries. The fact that many of the hypothesized links in our conceptual model were moderated by macro-level differences between reference and focal countries implies that more variables (e.g., cultural distance) could be used for testing contingencies in CI studies. Since, our study has shown that the CI phenomenon is affected by temporal-, spatial-, and product-related factors, it would be insightful to embark on studies having a longitudinal nature, covering a wide range of countries, and involving different types of products. There is also a need to encourage replication and cross-country studies to obtain an adequate volume of data that will allow the incorporation of additional constructs for the purpose of meta-analysis. In addition, the high coefficient value of the causal path between GCI and PCI necessitates a more in-depth methodological investigation of the discriminant validity of their measurement scales.

7.2 Implications for Managers

The results of our meta-analysis provide executives with valuable input regarding the key drivers and outcomes of foreign consumer GCI and PCI perceptions, thus helping them to formulate sound international business strategies. For example, our findings can guide important decisions concerning target market selection, market entry modes, brand positioning, and marketing mix adaptation in foreign markets. Managers can also use the findings of our study to better understand the mechanics of how their products are perceived by foreign consumers, and adjust their strategies accordingly. The results indicate that once consumers build favorable foreign CI perceptions (both at country and product levels), they subsequently develop positive evaluations of, favorable attitudes toward, and strong purchase intentions for foreign products. The strong positive influence of GCI on PCI found in our study also indicates that impressions about country characteristics are transferred into product characteristics, which managers should seriously take into consideration. Our findings also underline the role of product/brand familiarity in creating favorable GCI and PCI consumer perceptions, which implies that firms should enforce their global marketing efforts and consistently deliver superior value to foreign buyers. In doing so, it is important to seek the assistance of various foreign business associates, such as independent distributors/agents and joint venture partners, in contributing to the development of product and brand familiarity. They should also carefully select segments in international markets that are characterized by less ethnocentrism, animosity, and patriotism, as these have serious negative effects on CI perceptions. It is also important to pay attention to the demographic profile of the target market, particularly focusing on educated and affluent consumers who are more favorably predisposed toward foreign goods. Also, the fact that country differences with regard to economic development, innovativeness, industrial performance, and political risk were found to play a crucial role in moderating the drivers and outcomes of both GCI and PCI consumer perceptions underlines their importance as useful variables for segmenting the global market.

7.3 Implications for Policymakers

From a policymaking perspective, the underlined importance of GCI and PCI perceptions in foreign buying decision process implies a greater collaboration between public policymakers and indigenous firms to boost their home country’s credentials and qualities in the international marketplace and alleviate possible negative biases that may harm its image. For example, public policymakers could boost a favorable image by supporting internationally successful products and brands produced by local firms, as well as by requesting the latter to stress the origin of their goods in communication campaigns targeting foreign customers. National governments could also help to positively influence foreign consumer perceptions and behaviors through properly designed national export promotion programs, with a particular focus on educating their indigenous firms about the importance of CI (whether relating to the country or the product) in gaining foreign market acceptance. The fact that various country characteristics (e.g., economic, political, technological, social) usually translate into an image of the country in terms of its capabilities to develop, produce, and sell reliable products implies that national governments should convey a positive picture to other countries’ citizens, through promotional campaigns, news release in mainstream and social media, and nation brand building. Our analysis also revealed that there are certain macro-level factors (e.g., economic development, innovativeness, industrial performance, political risk) which can be effectively used by governments to strengthen the positive impact of their GCI and PCI in foreign markets.

8 Limitations and Future Research

The findings of our meta-analysis should be seen within the context of certain limitations, which can provide ideas for future research. First, in light of multiple inherent methodological problems in this line of research (e.g., the use of fictitious versus real products, different measurement scales, survey versus experimental data), the findings of our meta-analysis should be treated with some caution. Despite these problems, our study could provide an impetus for undertaking additional meta-analyses focusing on other lines of image research, such as that of place image, service country image, and store country image.

Second, our meta-analysis focused on key antecedents and outcomes of CI perceptions among foreign consumers. However, there is a growing body of research which focuses on the role of CI on industrial buying decision-making (for a review, see Dobrucalı, 2019). Moreover, the increasing share of services in international trade, and the concomitant growth of interest of CI studies focusing on services (e.g., Michaelis et al., 2008), requires to carry out a systematic assessment of the relevant literature and if possible a meta-analysis (provided a critical mass of articles will be secured).

Third, despite the potential antecedent (e.g., xenocentrism) or outcome (e.g., actual purchase) role of other important constructs associated with CI perceptions, we could not use them in our analysis due to insufficient data availability. Future research could narrow its focus and meta-analyze some selected links of variables with CI (whether GCI or PCI) instead of using broad models. For example, such links may include, on the antecedent side, global consumer personal values, country affinity, and brand nostalgia, and, on the outcome side, product preference, actual purchase, and brand loyalty.

Fourth, our analysis covered only articles published in English due to practical difficulties in having access to electronic databases of non-English articles, as well as limitations in reading articles in a language other than English. However, we acknowledge the fact that it is very likely for relevant CI articles to have been published in non-English journals for which we could not have an access. Hence, an investigation of specific non-English publication sources (e.g., German, French, Chinese) could yield further useful insights into the CI phenomenon.

Finally, since there are indications in some studies (e.g., Knight & Calantone, 2000; Leonidou et al., 2019) that CI perceptions may be influenced by consumers’ cultural traits, it would be illuminating to investigate the moderating role of Hofstede et al.’s (2010) cultural dimensions – individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and indulgence/restraint – on the various hypothesized associations between CI components and their antecedents and outcomes. Also, in light of the growing trend of online purchases of goods by foreign customers, future meta-analyses could examine possible moderating effects caused by online versus offline selling environments.

Notes

CI can be conceptualized at both country and product levels, with the former referring to the image transmitted by a country (called General Country Image or GCI) and the latter focusing on the image formed by consumers regarding the entire set of products from a particular country (called Product Country Image or PCI) (Pappu et al., 2007; Parameswaran & Pisharodi, 2002; Roth & Diamantopoulos, 2009; Roth & Romeo, 1992).

References

Ahmed, S., & d’Astous, A. (2008). Antecedents, moderators and dimensions of country-of-origin evaluations. International Marketing Review, 25(1), 75–106.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Prentice Hall.

Alba, J. W., & Hutchinson, J. W. (1987). Dimensions of consumer expertise. Journal of Consumer Research, 13(4), 55–59.

Ara, T. (2020). Country size, technology, and Ricardian comparative advantage. Review of International Economics, 28(2), 497–536.

Baker, W., Hutchinson, J. W., Moore, D., & Nedungadi, P. (1986). Brand familiarity and advertising: Effects on the evoked set and brand preference. Advances in Consumer Research, 13, 637–642.

Balabanis, G., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2008). Brand origin identification by consumers: A classification perspective. Journal of International Marketing, 16(1), 39–71.

Balabanis, G., Diamantopoulos, A., Mueller, R. D., & Melewar, T. C. (2001). The impact of nationalism, patriotism and internationalism on consumer ethnocentric tendencies. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1), 157–175.

Balabanis, G., Mueller, R., & Melewar, T. C. (2002). The human values’ lenses of country of origin images. International Marketing Review, 19(6), 582–610.