Abstract

Consumer resistance against corporate wrongdoing is of growing relevance for business research, as well as for firms and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Considering Fournier’s (1998) classification of consumer resistance, this study focuses on boycotting, negative word-of-mouth (WOM), and protest behavior, and these behavioral patterns can be assigned to the so-called “active rebellion” subtype of consumer resistance. Existing literature has investigated the underlying motives for rebellious actions such as boycotting. However, research offers little insight into the extent to which motivational processes are regulated by individual ethical ideology. To fill this gap in existing research, this study investigates how resistance motives and ethical ideology jointly influence individual willingness to engage in rebellion against unethical firm behavior. Based on a sample of German residents, PLS path analyses reveal direct effects of resistance motives, counterarguments, and ethical ideologies as well as moderating effects of ethical ideologies, which vary across different forms of rebellion. First, the results indicate that relativism (idealism) is more relevant in the context of boycott participation and protest behavior (negative WOM). Second and contrary to previous findings, this study reveals a positive effect of relativism on behavioral intentions. Third, individuals’ ethical ideologies do not moderate the effect of motivation to and arguments against engaging in negative WOM. On the contrary, the empirical analysis reveals significant moderating effects of relativism and idealism with regard to the effects of resistance motives and counterarguments on boycott and protest intention. Directions for future research and practical implications are discussed based on the study results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Ethical considerations are becoming increasingly important to buyers when making purchase decisions (e.g., Bray et al. 2011; Vitell 2015). Current market data show this shift in values. With 13.29 million German citizens preferring fair trade products in 2014 (Allensbach 2015), sales of fair trade products have risen more than 16 times from 2000 to 2014 (TransFair 2015). In addition to fair-trade consumption, through which shoppers reward companies for complying with ethical principles, consumers also have the power to punish unethical corporate conduct, hereinafter referred to as resistance. The phenomenon of consumer resistance as a response to unethical business practices has been addressed by several authors (e.g., Kozinets and Handelman 1998; Sen et al. 2001). Prior research has in particular considered boycotts (Hoffmann and Müller 2009; Yuksel and Mryteza 2009; Klein et al. 2004). In 2013, 36% of German consumers boycotted a company, and 29% discouraged somebody from buying brands or products from a specific company (Ipsos 2014). In addition, and driven by internet technology, new forms of resistance have emerged in recent times. For example, blogging activities and online petitions are new threats to corporations. In particular, online protest movements have enormous reach and have immensely gathered momentum due to the instant reactions of internet users to corporate misconduct. The issue of whether consumer resistance directly affects company performance is controversial (e.g., Hong et al. 2011; Koku et al. 1997). However, the notion that, for instance, boycott campaigns may harm an organization’s image and may thus affect companies’ bottom lines indirectly is mainly unchallenged (Klein et al. 2004). Therefore, it is of significant importance for accused businesses and opposing non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to know how motivating and demotivating factors drive individual consumer resistance. In particular, more detailed information on the varying effects of the considered behavioral determinants across different forms of consumer resistance would be advantageous. Moreover, recommendations about how these organizations should target segments of consumers with various ethical positions would be useful, too. The current study aims to provide insights into these issues of business ethics research.

Prior empirical research has in particular identified different categories of motives as major determinants of consumer resistance behavior. For example, regarding boycott participation, John and Klein (2003) highlight the relevance of instrumental and non-instrumental resistance motives. According to general theories of motivation (e.g., Elliot and Friedman 2007), on the one hand, these motives may drive consumer behavior toward actions of resistance; boycott participation thus represents an approach goal. On the other hand, negatively valenced aversive motives (e.g., not forgoing a beloved product) are decisive, too, and consumers may thus regard acts of resistance as avoidance goals. To incorporate the notion of avoidance goals, the present study considers arguments against resistance as well. In the context of boycotts, some studies (e.g., Lindenmeier et al. 2012) have investigated how individual evaluations of unethical business practices affect consumer behavior.Footnote 1 Whereas ethical evaluations are situational in nature and thus vary across different cases of corporate wrongdoing, intrinsic ethical ideologies (i.e., idealism and relativism) are considered to remain relatively stable over time and resist external influences (Tansey et al. 1994). Therefore, the current study first adds ethical ideology to the determinants of individual consumer resistance. The authors assume that considering ethical ideology instead of ethical evaluation leads to findings with greater external validity. In addition, targeting strategies can be more efficiently tailored to more stable segments of consumers with homogenous ethical positions. Second, this study is the first to investigate the moderating effects of ethical ideologies on the relationship between motivational constructs and ethical intentions in a business context. Hence, the current study provides new insights into how ethical ideology regulates the effects of motivating and demotivating constructs on individual inclination toward consumer resistance. Negative word-of-mouth (WOM) behavior, for example, has been widely neglected in consumer resistance literature, as Grappi et al. (2013) state. Third, considering this gap in research, the present study considers negative WOM and protest behavior as further forms of so-called active rebellion, which is regarded as a subtype of consumer resistance. The present research hence provides more detailed information on the varying effects of motivational and ideological constructs on individual inclination toward these forms of resistance.

This study analyzes the effects of motivational and ideological constructs as well as the moderating roles of idealism and relativism on the intention to engage in different forms of consumer resistance. In doing this, the following section provides readers with a definition and classification of the consumer resistance phenomenon. Moreover, research hypotheses are delineated in Sect. 3. The research approach and study design are presented in Sect. 4, followed by the study results. The Sect. 5 discusses the study findings. The paper concludes with practical implications, study limitations, and avenues for future research.

2 Defining consumer resistance and active rebellion

The phenomenon of resistance has gained relevance in diverse fields of research such as youth studies (Raby 2005), cultural sciences (Williams 2009) or peace research (Sørensen and Vinthagen 2012). Ad busting, tattooing, punk or goth subcultures, protest actions against trade liberalization, or societal disengagement are examples of different forms of resistance (Raby 2005). According to Hollander and Einwohner (2004), a multitude of understandings of the concept of resistance exists. Hollander and Einwohner (2004) highlight “action” and “opposition” as core elements of all types of resistance. Moreover, these authors state that the degree of recognition or visibility of acts of resistance as well as of individual intent or consciousness have to be considered as dimensions of variation. According to Raby (2005, p. 153) “resistance is oppositional, aiming to disrupt, or gain the upper hand in, what actors perceive to be dominant power relations.” Likewise, Poster (1992, p. 1) defines resistance as “the way individuals and groups practice a strategy of appropriation in response to structures of domination.”

Penaloza and Price (1993) transfer the understanding of resistance of authors such as Poster (1992) to the field of business economics. In this context, market systems and multinational corporations are regarded as structures of domination (Rudmin and Richins 1992). According to Fournier (1998), a significant proportion of citizens hold a general skepticism toward marketing practices and consumption itself. For instance, persistently repeating cycles of product innovation and the resulting overload of new consumption opportunities are emotionally burdensome. As another example, consumers feel anger because of corporate conduct that they perceive to be unethical (e.g., acceptance of child labor in the production chain). In sum, the dominant structures responsible for these dissatisfying events represent a cause for perceived loss of control on the side of the consumers, and consumer resistance can thus be regarded as an attempt to take over control again. In line with this notion, Penaloza and Price (1993, p. 123) state that consumers do not accept being passive recipients of marketing activities but enter a “recursive interplay” with corporations. Consumer resistance may focus on the market as a whole or specific products and brands as well. Against this background, consumer resistance can be defined as an effort against the domination of, for instance, multi-national corporations and can be used to regain consumer sovereignty by means of purchasing power (Fournier 1998).

Consumer resistance resembles other phenomena such as anti-consumption, which postulates the rejection of consumerism and motivates people to engage in self-restraint. However, Lee et al. (2011) dissociate consumer resistance from anti-consumption by stressing that the rebellion of consumers against dominant market forces and the focus on power issues are key characteristics of resistance. This study investigates the effect of ethical ideologies on individual behavior. Crane and Matten (2010, p. 370) define ethical consumption as “the conscious and deliberate choice to make certain consumption choices due to personal moral beliefs and values”. Hence, this study assumes consumer resistance to be congruent with ethical consumer behavior to a large extent. Finally, because different types of consumer resistance such as boycotting (e.g., Klein et al. 2004) or negative WOM (Hennig-Thurau and Walsh 2003) are not only motivated egoistically but are also instruments that may serve the good of a greater group of people, resistance overlaps with prosocial behavior, too.

Previous literature offers several approaches to the classification of the different forms of consumer resistance. For example, Penaloza and Price (1993) differentiate between individual and collective resistance actions (e.g., negative WOM vs. boycotting), as well as between radical and reformist resistance (protesting vs. lifestyles of voluntary simplicity). The distinction between radical and reformist consumer resistance alludes to the pursued goal. Reformist (radical) consumer resistance aims at cautiously and gradually (instantly and fundamentally) changing current economic structures. Cherrier (2009) classifies consumers according to their motivations for engaging in different types of resistance. Whereas consumers who participate for reasons of social change are assigned to the category of “hero resistant resistance identities,” the category of “project resistant resistance identities” subsumes consumers who engage in resistance due to their self-discovery motivation. In addition, Penaloza and Price (1993) distinguish between acts of resistance that aim to alter the meaning of products (e.g., alienating products from their original purpose) or to alter the marketing mix (e.g., fighting against advertising campaigns). Ritson and Dobscha (1999) suggest another classification approach: observable actions (e.g., public criticism) are named not-futile resistance by these authors, whereas non-observable or silent actions (e.g., single consumers refraining from consumption) are labeled as futile resistance.

Fournier (1998) presents a continuum of consumer resistance that ranges from (1) avoidance behaviors (i.e., avoiding specific brands or products) via (2) minimization behaviors (i.e., coping behavior and downsizing) to (3) active rebellion. Considering this continuum, the present paper focuses on active rebellion. Based on the classification approaches mentioned above, the considered forms of active rebellion represent radical and hero resistance types of consumer resistance. According to Fournier’s (1998) classification, active rebellion manifests itself in the form of complaining or boycotting behavior as well as dropping out. The notion of active rebellion alludes to Hirschman’s (1970) theory, which states that dissatisfied consumers may exit the relationship they have with a company, voice their frustration by directly complaining to the company, or remain loyal to the company. Based on Hirschman’s (1970) classification, consumer boycotts represent a type of exit behavior. Friedman (1985) defines consumer boycotts as attempts of activist groups to achieve certain goals by motivating consumers to refrain from purchasing products of one or more companies. According to Garrett (1987), consumer boycotts are campaigns of NGOs that are not legally binding and that try to stop transactions between consumers and specific companies. Negative WOM as well as protest behavior are specific forms of voice behavior. Voice behavior patterns have the potential to alert others to issues, gain their interest, and thus challenge the company to change its corporate behavior. Negative WOM represents a voice behavior and is considered a reaction to dissatisfaction. Individuals share information about unfavorable incidents in the consumer sphere by means of sharing negative WOM with their family, friends, and acquaintances (Richins 1983). The present study considers so-called “protest behavior” as a collective type of voice behavior. According to Grappi et al. (2013), protest behavior are alternative patterns of consumer reactions to corporate irresponsibility. These patterns include blogging against companies on the internet, supporting NGOs by donating to them, or participating in collective actions such as demonstrations or joining petitions.

3 Hypotheses development

3.1 Effect of resistance motivation

According to classical motivation theory (e.g., Maslow 1943) and prior research on the role of desires in goal-directed behavior (cf. Perugini and Bagozzi 2001), unfulfilled needs and wants are key behavioral determinants. More precisely, unfulfilled desires and needs activate motives that in turn lead to goal-directed behavior. Based on Klein’s (2001) paper on boycotting behavior, this study distinguishes between instrumental and non-instrumental motives of active rebellion. Supporters of boycotts are driven by instrumental motives because they regard refraining from consumption as an instrument to influence corporate behavior (Friedman 1985; Kozinets and Handelman 1998; Friedman 1999; Klein et al. 2004). According to this approach, boycott intention is affected by the perceived efficacy of the boycott and the expected boycott participation (Sen et al. 2001), which should enhance individual willingness to participate (John and Klein 2003). People cooperate in situations of social dilemma when they assume that there is a high probability of the collective goal being achieved (Wiener and Doescher 1991). Another instrumental motive for participation lies in anticipated triumph derived from the idea of contributing to a successful protest action (John and Klein 2003). Moreover, irresponsible management decisions can cause damage to third parties (e.g., factory workers or environmental damage). Therefore, consumers can be altruistically motivated to participate in prosocial acts of resistance. They could help others by trying to stop corporate wrongdoing through boycotting (John and Klein 2003) or could engage in negative WOM to help others through information-sharing (Cheung and Lee 2012; Alexandrov et al. 2013).

Non-instrumental motives are intrinsic; therefore, they are assumed to influence resistance behavior irrespective of the success or failure of action (Klein et al. 2004). From this perspective, active rebellion can be motivated by a strong desire to shout one’s anger about unethical corporate conduct (John and Klein 2003). According to Wetzer et al. (2007), those in an angry state of mind, in particular, engage in negative WOM to express their feelings and take revenge. Moreover, consumers may also participate to punish companies for unethical conduct (John and Klein 2003). Research on prosocial behavior suggests that recognition by others can be a decisive impetus to help, whereas refraining from helping may have negative emotional consequences such as self-reproach or public denouncement (Dovidio et al. 1991). Boycott participation can, therefore, serve as a form of moral self-enhancement (John and Klein 2003). The individual’s self-esteem is fostered by advocacy for a cause and solidarity with others (Klein et al. 2004). Self-enhancement also drives negative WOM (Angelis et al. 2012; Wojnicki and Godes 2008). In accordance with the moral cleansing process (Kozinets and Handelman 1998) and the moral obligation of clean hands (Smith 1990), resistance motives can be based on feelings of moral superiority. Clearly, the avoidance of shame and guilt is also relevant in this context (Klein et al. 2004).

To keep this study’s model of active rebellion parsimonious and because previous research has already investigated the effects of motives on consumer resistance behavior, resistance motives are conceptualized as a higher-order construct. Both instrumental and non-instrumental motives contribute to the superordinate concept of resistance motives but vary independently. The fact that there is no causal flow from the superordinate construct to the subordinate dimensions implies that instrumental and non-instrumental motives should be formative indicators of resistance motives, and the construct is hence conceptualized as a reflective-formative hierarchical latent variable model. More precisely, the higher-order construct “resistance motives” is formed by the lower-order constructs “instrumental motives” and “non-instrumental motives.” Based on this conceptualization, motives are assumed to affect resistance inclination, and hypothesis H1 thus reads as follows:

H1

Resistance motives have a positive effect on the intention to participate in different forms of rebellion against alleged corporate wrongdoing.

3.2 Effect of arguments against resistance

Sen et al. (2001) and Klein et al. (2004) consider the costs of participation in their studies on consumer boycotts, subsequently referred to as “counterarguments”. These arguments against resistance should weaken the willingness to engage in resistance (Hoffmann 2011). According to Klein et al. (2004), the decision for or against participation represents a cost-benefit analysis and has to be considered in the broader context of prosocial behavior. Considering Dovidio et al.’s (1991) cost-reward approach, participation costs are expected to have a negative effect on individual inclination toward consumer resistance.

This study considers a two-fold conceptualization of counterarguments. First, negative outcomes such as job cuts in boycotted companies can discourage individuals from participating (Klein et al. 2004). Moreover, individuals may refrain from rebellion due to the perceived incapacity to achieve change, resulting in the so-called “small-agent problem” (John and Klein 2003). In addition, consumers may regard participation as an unnecessary expense because others are already cooperating and, therefore, may be inclined to free-ride on the efforts of others (Klein et al. 2004). These arguments against resistance represent “social dilemma-related” costs. Second, Klein et al. (2004) consider a further, “product preference-related” cost category, namely, constrained consumption. Sen et al. (2001), likewise, focus on costs in terms of withholding consumption, measured by substitutability and product preference. The costs of withholding consumption are expected to be higher with limited availability of substitutes.

Hoffmann (2011) subsumes counterarguments under the notion of participation inhibitors and also distinguishes between the two facets “constrained consumption” and “disbelief in efficacy”. In line with Hoffmann’s (2011) notion, this paper considers counterarguments to be a multifaceted construct with arguments related to social-dilemma phenomena and to consumers’ product or brand preferences as subordinate dimensions. Thus, the higher-order construct “counterarguments” is formed by the lower-order constructs “product preference-related” and “social dilemma-related” costs. Based on this conceptualization, counterarguments are assumed to affect resistance inclination, and hypothesis H2 thus reads as follows:

H2

Counterarguments have a negative effect on the intention to participate in different forms of rebellion against alleged corporate wrongdoing.

3.3 Ethical ideologies

Previous research reveals that moral judgment may have a distinct effect on consumer behavior. Lindenmeier et al. (2012), for example, show that the moral assessment of alleged corporate misconduct affects consumer outrage, which subsequently impacts individual boycott inclination. Moral evaluations of an ethical issue may vary across individuals, and previous research proposes processes and results of learning (e.g., Bandura 1990) and moral development (e.g., Kohlberg 1983) as factors that may explain these variations. Similarly, authors such as Hunt and Vitell (1986) state that moral judgments represent situational evaluations. Hence, moral judgments are contextual in nature and also depend on individuals’ personal experiences. This insight suggests that persons with different cultural backgrounds and experiences can come to different moral conclusions. Forsyth (1980), however, found that individuals, when exposed to the same ethical situation, do not necessarily come to the same moral judgment. Therefore, the influence of context on moral judgment is limited, too, and this may be explained by the fact that individuals differ regarding the moral criteria they consider when making an ethical decision (Barnett et al. 1998). In line with this reasoning, individuals arrive at diverse moral judgments because they look at an ethical issue from different ethical positions (Barnett et al. 1998).

To assess these ethical positions, Forsyth (1980) has developed the ethics position questionnaire (EPQ). Forsyth’s (1980) concept is based on classical ethical theories and the EPQ condenses these into two dimensions (Barnett et al. 1996). More precisely, the EPQ measures individual ethical positions in terms of two independent dimensions (i.e., relativism and idealism) that remain relatively stable over time and across different objects of evaluation. First, relating to the relativism dimension, they differ in the degree to which they accept or reject universal moral rules. Second, with regard to idealism, individuals vary in their belief about whether “desirable consequences, can with the ‘right’ action, always be obtained” (Forsyth 1980, p. 176) or whether negative consequences have to be accepted sometimes in order to achieve a favorable outcome on the societal level. Instead of assuming that individuals are oriented to relativism or idealism, every individual finds him- or herself located on both continua of moral philosophies. Forsyth (1980) thus states that both the weighing of idealistic and relativistic principles can vary independently of each other (Forsyth 1992).

3.3.1 Effect of idealistic ideology

The idealism dimension of the EPQ scale, in particular, subsumes deontological and teleological ethical philosophies. Deontological philosophy represents an ethics of duties, which is greatly based on the idea of self-determination (Crane and Matten 2010). Deontology implies that individuals can only be held responsible for things within their sphere of influence. According to duty ethics, individuals should only act according to guiding principles that hold true for everybody at any time. Kant’s (1870) categorical imperative as the most prominent example of such guiding principles implies that there is an absolute and universal truth. This view is referred to as universalism (Healy 2007), and individuals who are inclined toward deontology implicitly deny the co-existence of different moral norms. Gilligan’s (1982) ethics of caring shares parallels to the idealism dimension of Forsyth et al. (1988), too. This ethical philosophy suggests that there are considerable differences in the extent to which individuals include the universal ethical principle of never doing harm to others in their judgments and decisions. Moreover, idealists reject ethical egoism insofar as they, for instance, condemn companies as egoistically profiting from inhumane working conditions in development countries. Contrary to duty ethics, teleological philosophies, state that ethicality of action should be judged by its consequences for the whole society and are, therefore, often referred to as consequentialist ethics (Crane and Matten 2010). According to utilitarianism (Bentham 1879; Mill 1901), which can be assigned to hedonistic teleological approaches, actions that result in the highest level of happiness for the largest number of people possible are to be considered ethically superior. Thus, teleology accepts practices that harm individual welfare when goals on the societal level can be achieved through them.

Idealism considers teleology and deontology as endpoints of one continuum, similar to Brunk’s (2012) concept of consumer-perceived ethicality. More precisely, idealists judge between right and wrong, fair and unfair, and thus between what is ethical and unethical based on the well-being of other persons (Swaidan et al. 2003). Therefore, highly idealistic people hold the opinion that doing harm to others should categorically be avoided. As a result, highly idealistic persons would never choose an option with negative consequences for third parties (Forsyth 1992). In contrast, non-idealistic people do not judge and act according to such ideals. They hold the view that negative side effects occasionally have to be accepted to achieve good overall outcomes (Forsyth 1980; Schlenker and Forsyth 1977). Because of the teleological guiding principle that doing harm to others is acceptable when positive outcomes prevail, teleology is a non-idealistic philosophy (Barnett et al. 1996). According to Forsyth (1980), deontologists are high idealists, and teleologists are low idealists. Furthermore, idealism is associated with stronger perceptions of moral intensity (Singhapakdi et al. 1999). Hence, idealists are more inclined to respond to the vulnerability of the people and cannot keep aloof from human suffering. Low idealists instead apply the utilitarian approaches mentioned above. From an idealist’s perspective, utilitarian approaches would assumingly not lead to the desirability of outcomes in which they believe deeply (Forsyth 1980); therefore, idealists should reject teleological views. The assumption of innate rights to life, happiness, and liberty supports this notion as well. The recognition of natural rights of all human beings (Locke 1821) substantiates the idealists’ inclination to protect these rights. Because consumer resistance can be classified as a prosocial behavior, idealists assumedly consider consumer resistance as a viable means to remedy human suffering (e.g., putting a stop to child labor in developing countries by boycotting companies that use child labor). In line with this notion, idealism positively affects the perceived importance of ethics and social responsibility (Singhapakdi et al. 1995) and has been identified as a driver of ethical consumption (Marta et al. 2003; Singhapakdi et al. 2000, 2008; Vitell and Paolillo 2004; Newstead et al. 1996) and as an obstacle to unethical behavior (Rawwas et al. 2004). Considering this line of argumentation, hypotheses H3a reads as follows:

H3a

Idealism has a positive effect on the intention to engage in active rebellion against alleged corporate wrongdoing.

3.3.2 Effect of relativistic ideology

Relating to the relativism dimension of the EPQ approach, discourse ethics, which is strongly influenced by the protagonists of the so-called Frankfurt School, questions ethical philosophies such as deontology or teleology and suggests relativism instead (Holzmann 2015). With regard to deontology, relativists reject that individuals are able to derive universal moral principles that are capable of guiding their behavior in an ethical direction because they cannot free themselves from their own interests. Especially on a global scale—on which the contemporary business world operates—actions have always unknown consequences that cannot be fully grasped by a single person. Moreover, relativists hold the opinion that teleological ethical philosophies support the oppression of minority groups insofar as utilitarianism prioritizes public welfare over the welfare of the individual (Holzmann 2015). Discourse ethics, on the contrary, assumes that no universal rules exist and that moral norms and values can only be identified in a fair and open discourse between all parties involved (Habermas 1991). Hence, the related ethical position of relativism suggests, first, the coexistence of different ethics due to different cultural societies and, second, that all of them can be morally right at the same time (Donaldson 1996). Therefore, discourse ethics turns away from absolute normative directives and proposes the generation of norms in a process of reflection instead (Crane and Matten 2010). In line with discourse ethics, the concept of ethical skepticism also accepts that various moral perspectives exist and, therefore, rejects ethical viewpoints, which are based on universal moral rules (Schlenker and Forsyth 1977).

Highly relativistic people, or ethical skeptics, hold the view that morality is situational and dependent on the involved individuals (Forsyth 1980). Therefore, they weigh circumstances higher than absolute ethical principles. This is also suggested by situation ethics, a subtype of ethical skepticism, which calls for “contextual appropriateness—not the ‘good’ or the ‘right’ but the fitting” (Fletcher 1966 p. 27–28). Non-relativists, however, rely on universal principles such as both deontologists and teleologists do. For instance, relativists would not automatically hold a negative opinion toward inhumane employment conditions for workers by applying deontological rules. Instead, they would put the issue into the context (e.g., variation of labor standards across developing countries) and then judge under consideration of these circumstances. Furthermore, and because relativists accept the co-existence of different cultural value systems (Donaldson 1996), it is unlikely that they strive at imposing standards that are valid in western society on other cultural spheres as strongly as idealists do.

The effects of relativism on behavioral intentions have been investigated in different contexts related to business ethics (e.g., Rawwas et al. 2013; Cadogan et al. 2009). According to Singhapakdi et al. (1995), the perceived importance of social responsibility is negatively affected by relativism. Vitell and Paolillo (2004) also confirmed a negative relationship of relativism with the perceived importance of ethical issues for entrepreneurial success. The more relativistic the ethical position, the less importance is attached to the ethical boundary conditions of business success. Moreover, relativism is associated with decreased perceived moral intensity (Singhapakdi et al. 1999). Hence, relativists have lower problem perception within the course of ethical dilemmas. They are thus able to have more distance from human suffering and are capable of focusing on context more strongly. According to Shaub et al. (1993) and Sparks and Hunt (1998), highly relativistic individuals show lower ethical sensitivity as well. This indicates again that they are less inclined to respond to the suffering and vulnerability of the people. Moreover, relativistic people are more likely to accept unethical business behavior (Rawwas et al. 1994) or even to get involved in it since relativism has been identified as a driving force for unethical behavior (Rawwas and Isakson 2000). This negative relationship between relativism and ethical behavior has been confirmed by several empirical studies (Erffineyer et al. 1999; Singhapakdi et al. 1995, 1999; van Kenhove et al. 2001). Analogous to these findings, Vitell et al. (1991) and Nebenzahl et al. (2001) show that the inclination to engage in ethical consumption decreases with relativism. Thus, relativists assumingly are more inclined to, for example, accept inhumane working conditions in developing countries and are subsequently less motivated to fight against companies that benefit from this type of allegedly unethical conduct. Against this theoretical background, hypothesis H3b is as follows:

H3b

Relativism has a negative effect on the intention to engage in active rebellion against alleged corporate wrongdoing.

3.4 Moderating effects of ethical ideologies

Cherrier et al. (2011) define resistant consumers as rational individuals who carefully consider their buying decisions. They decide whether a company is to be punished for unethical conduct or to be rewarded for ethicality and responsibility. This implies the existence of a superordinate normative framework that guides consumers when they, for instance, abandon their favorite products (Cherrier et al. 2011). Ethical ideologies represent such a superordinate reference system, which embeds individuals in their social environments and regulates their behavior. Correspondingly, as Tansey et al. (1994) highlight, individuals who differ in their idealistic and relativistic ideology come to different moral judgments and should thus behave in a different manner. Against this theoretical background, it can be assumed that the inclination toward the considered forms of active rebellion varies among individuals with different manifestations of idealism and relativism. Therefore, this study suggests that ethical ideologies moderate the effects of motives and counterarguments on the intention to participate in active rebellion.

3.4.1 Moderating effects of idealism

Previous research (McHoskey 1996) found a positive relationship between idealism and individuals’ inclination toward authoritarianism. The acceptance of authorities indicates that idealists are less likely to violate organizational or social rules (Hastings and Finegan 2011). The work of Henle et al. (2005) and Hastings and Finegan (2011) suggest that idealistic people show little deviant behavior and follow standards. Park (2005) investigated the relationship between ethical orientation and interaction with the social environment. He found that highly idealistic individuals are more likely to behave in accordance with organizational control systems, whereas relativistic individuals react more strongly in response to their peers’ behavior. As aforementioned, resistance can be defined as the attempts of individuals or groups of individuals to overcome dominant structures of societal or economic power (Poster 1992). The current study assumes that idealists’ inclination toward obeying rules keeps these individuals from engaging in consumer resistance. This is due to the notion that rebellious actions imply, to a certain degree, a breach of social norms. Hence, idealism should dampen the effects of resistance motives (e.g., venting one’s anger) on individuals’ inclination toward active rebellion. Considering this reasoning, hypothesis H4a1 is as follows:

H4a1

Idealism moderates the effect of resistance motives on the intention to engage in active rebellion against alleged corporate wrongdoing: If idealism is high (low) the effect of resistance motives on behavioral intentions becomes less (more) positive.

The current study conceptualizes arguments against consumer rebellion based on a differentiation of arguments related to social-dilemma issues and product preference. From a social-dilemma perspective, participation in resistance can be compared to the production of a public good, for which free-riding incentives and the small-agent problem are prevalent (Klein et al. 2004). Considering this facet of consumer resistance, idealists presumably regard free-riding as an unethical act and, therefore, do not allow themselves to be seduced into opportunistic behavior (Rawwas et al. 2004). Moreover, due to their inclination toward universal rules to doing good, the small-agent rationale does not dissuade idealistic persons from trying to help others by means of resistance. In addition, Muncy and Eastman (1998) show that materialism is correlated with low ethical standards. Idealists, however, have high ethical standards and focus strongly on the welfare of others. Thus, in line with the Kantian categorical imperative, they are not very likely to choose an option associated with negative consequences for third parties for selfish reasons such as satisfying materialistic consumption needs. Along this line of argument, it is assumed that the preference for products or brands is a less decisive counterargument for idealists. Hence, hypothesis H4a2 is formulated as follows:

H4a2

Idealism moderates the effect of counterarguments on the intention to engage in active rebellion against alleged corporate wrongdoing: If idealism is high (low) the effect of counterarguments on behavioral intentions becomes less (more) negative.

3.4.2 Moderating effects of relativism

Universal moral rules do not apply for relativistic persons (Forsyth 1980). For relativists, the answer to the question of whether, for instance, an allegedly corporate misconduct is in fact immoral is contingent on the social and cultural context (Smith and Cooper-Martin 1997), and moral judgment thus depends “on the nature of the situations and circumstances” (Park 2005, p. 83). In particular, according to Park (2005), relativists’ assessment of ethical issues is based on skepticism and does consider other judging criteria than absolute moral rules (e.g., the categorical imperative). In line with this notion, the current study assumes that relativists use the level of non-instrumental motives as a piece of situational and contextual information. Non-instrumental motivation is driven to a large part by consumers’ anger and frustration about corporate behavior (John and Klein 2003). According to Tangney et al. (2007, p. 347) these negative emotions may serve as an “emotional moral barometer” signaling to relativistic individuals how to evaluate an ethical issue or whether they should adjust their behavior to a specific situation. Therefore, the effect of emotion-induced non-instrumental resistance motivation should increase with relativism. Furthermore, and inversely to idealism, relativism is negatively correlated with the liking and acceptance of authoritarianism (McHoskey 1996). Therefore, as Mudrack (2005) state, relativistic individuals show a less strong inclination for adherence to organizational rules. In addition, and because relativism is to a greater extent culturally driven, relativistic people react more strongly to peer behavior (Park 2005). When they expect others to be susceptible to normative influence, too, they are supposedly more confident about exerting an influence on their peers than non-relativists and taken in by an illusion of control. This illusion of control leads to an overestimation of the impact of one’s own actions (Fiske and Neuberg 1990). In the consumer resistance context, individuals with a high illusion of control assume that they can directly affect company behavior or the behavior of their fellows. Therefore, due to the subsequently higher expectation of overall participation, relativistic individuals anticipate a higher success likelihood of attempts to overcome structures of economic power by means of consumer resistance. This study thus assumes a stronger effect of instrumental motives on goal-directed behavioral intentions of relativistic consumers. The goal-gradient hypothesis (Hull 1932) serves as a theoretical foundation for the moderation effect of relativism. The individual motivation and effort to achieve a behavioral goal increases with the perceived psychological proximity of an approach goal according to this hypothesis (e.g., Kivetz et al. 2006). It can be assumed that relativistic individuals perceive a higher goal proximity due to a higher perceived success likelihood and instrumental motives should thus have a stronger effect for these persons. Against this background hypothesis H4b1 is as follows:

H4b1

Relativism moderates the effect of resistance motives on the intention to participate in different forms of rebellion against alleged corporate wrongdoing: If relativism is high (low) the effect of motives on behavioral intentions becomes more (less) positive.

This study also assumes a moderating effect of relativism on the effect of counterarguments on consumer inclination toward active rebellion. Machiavellianism is positively correlated with relativism (Al-Khatib et al. 2016; Davis et al. 2001; Leary et al. 1986; Rawwas et al. 1994). Machiavellianism represents “the view that politics is amoral and that any means however unscrupulous can justifiably be used in achieving political power” (Merriam-Webster n.d.). This implies that Machiavellian relativists pursue the target of achieving power with every emphasis. Thus, it can be assumed that relativists will not be easily moved from the path to power by obstacles standing in their way. As mentioned above, consumer resistance comprises attempts to fight existing structures of economic power (Poster 1992). Therefore, carried over to the current study, counterarguments should be less decisive for relativistic consumers since they remove these psychological obstacles purposely out of their way. This line of thought results in H4b2:

H4b2

Relativism moderates the effect of counterarguments on the intention to engage in active rebellion against alleged corporate wrongdoing: If relativism is high (low) the effect of counterarguments on behavioral intentions becomes less (more) negative.

4 Empirical study

4.1 Study design

As an example of corporate wrongdoing, this study uses chocolate manufacturers tolerating abusive child labor at West African cocoa plantations, a business practice that has been criticized and morally condemned by several NGOs. A great many West African cocoa plantations face allegations of abusive child labor and inappropriate working conditions. Leading companies in the chocolate industry are subject to public scrutiny for benefiting from an inexpensive cocoa supply. Public opinion research illustrates the relevance of this issue for German citizens. Close to 80% of consumers classify “no child labor” as a purchase-deciding criterion (Forum Fairer Handel 2010), and 60% of consumers would refrain from buying products from companies with salaries below average or that use child labor in their supply chain (Statista 2007).

The study encompasses 420 respondents, and data collection was conducted in cooperation with an online panel company in October 2015. German residents aged 18–65 were identified as the population of interest. A quota sample procedure was applied by the panel company with gender and age as the quota criteria to ensure the proper representation of the population of interest. Table 1 depicts the distribution of female and male respondents across age groups, educational qualifications, and citizenship. The sample underrepresents the share of the population without German citizenship status, which actually accounts for approximately 10% of the total German population.

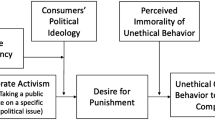

At the beginning of the online survey, information on the use of child labor and inhumane working conditions at West African cocoa plantations, as well as on a fictitious NGO campaign, were provided to the interviewees. Moreover, respondents were told which leading companies are alleged to process cocoa from such plantations. Considering the idea that consumer resistance can aim to change the marketing mix of companies, study respondents were asked to assess if participation in (1) a boycott, (2) negative WOM, or (3) protest behavior would be viable options to rebel against the unethical business practices described. Subsequently, respondents were asked to answer questions to measure the constructs of the model (see Fig. 1). The participants of the survey were asked to answer the questions truthfully, and the authors guaranteed anonymity of respondents. This procedure should have lowered the respondents’ inclination to give socially desirable answers that did not honestly reflect their true thoughts.

Conceptual model. Note The study considers three dependent variables, which are measured by means of two three-item measurement scales and one five-item measurement scale (see “Appendix 1”)

4.2 Measures

One part of the constructs depicted in Fig. 1 was measured by means of reflective multi-item measurement instruments. The measures for the three behavioral intentions considered were mainly adopted from Grappi et al. (2013). More precisely, the present study considers a three-item reflective measure for negative WOM intention. In addition, the study measures boycott intention by means of a three-item reflective measure, too, which is formulated with reference to Klein et al.’s (2004) or Lindenmeier et al.’s (2012) instrument. We deleted one item of Grappi et al.’s (2013) reflective protest scale’s items that alludes to legal action due to problems with understandability that appeared in a pretest. Moreover, this study’s protest intention instrument considers two refined items (see “Appendix 1”): First, item P_2 condenses the items that originally asked the interviewees about their inclination toward picketing and actions of resistance. Second, item P_5 concretizes Grappi et al.’s (2013) measure that refers to the support of social movements.Footnote 2 The questionnaire included the items of Forsyth’s (1980) Ethics Position Questionnaire (EPQ) to measure individual ethical ideology. The EPQ consists of ten reflective question items for idealism and relativism, respectively. Contrary to, for instance, Strack and Gennerich’s (2007) study results, a preceding exploratory factor analysis did not confirm Forsyth’s assumption of a two-dimensional factorial structure of ethical ideologies. The factor analysis resulted in a four-dimensional solution with two factors that solely correlated with a small number of items. Considering this result, we deleted seven items due to high double loadings and high loadings on the two aforementioned factors. Deleting further items with low outer PLS loadings and considering the results of a confirmatory factor analysis, the final measurement instrument consists of five idealism items and four relativism items.Footnote 3 Other authors such as Davis et al. (2001), Redfern and Crawford (2004), Cui et al. (2005), or Steenhaut and van Kenhove (2006) had to reduce the original EPQ scale in a similar manner.

The counterarguments construct was considered as a reflective-formative higher-order construct because it is assumed to be formed by the social dilemma-related and product preference-related arguments against consumer rebellion. The concept of higher-order measurement models allows research to conceptualize and operationalize more complex phenomena than the constructs commonly considered in behavioral research. Higher-order constructs usually consist of “two layers of constructs” (Hair et al. 2016, p. 281). We assume that the higher-order construct “counterarguments” is formed by the lower-order constructs “product preference” costs and “social dilemma” costs. To avoid distortions between the lower-order constructs, they were measured with the same number of indicators (Becker et al. 2012). Resistance motives were operationalized as a reflective-formative construct, too. The lower-order constructs instrumental and non-instrumental motives were measured considering approaches of John and Klein (2003), Klein et al. (2002), and Klein et al. (2004). The number of indicators deviates across the lower-order motives constructs. The study used the so-called “repeated indicators” approach (Becker et al. 2012) to operationalize both considered higher-order constructs. This means that all indicators that are used to measure the lower-order constructs are pooled to measure the higher-order constructs (Hair et al. 2016). Moreover, referring to all constructs considered in this study’s model, measurement was based on seven-point Likert scales, from 1 = “totally disagree” to 7 = “totally agree.” The exact wording can be found in the Appendix 1.

To assess individual item reliability, the loadings of the indicators have been estimated for all reflective items. The results (see “Appendix 1”) show that the majority have values greater than 0.70. Only two indicator loadings for relativism and one for non-instrumental motives are below 0.70. The Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) values exceed the thresholds of 0.70, 0.70, and 0.50, respectively, for all constructs. Hence, all reflective constructs show convergent validity and internal consistency. Discriminant validity is confirmed by comparing the square roots of the AVEs to all corresponding interconstruct correlations. The Fornell–Larcker ratio is below the recommended threshold of 1.0 for all constructs (see Table 2).

The reliability of the lower-order constructs’ items is ensured because almost all indicator loadings exceed the critical threshold of 0.70 (see “Appendix 1”). As α, AVE and CR values are above the threshold values of 0.70, 0.50 and 0.70, respectively, convergent validity and reliability can be confirmed for both lower-order constructs. According to Becker et al. (2012), the coefficients of the paths from the lower-order constructs to the higher-order constructs represent the formative weights (see Fig. 2). All formative weights are significant, and the sign value of the weight confirms results as expected. Moreover, as the VIF values are 1.43 for the lower-order facets of counterarguments and 2.32 for the first-order constructs of motives, there are no multicollinearity issues. Taken together, the appropriateness of the hierarchical latent variable measurement models can be confirmed.

4.3 Results of the PLS path analyses

To validate the proposed hypotheses, the study used partial least squares (PLS) and tested the model considering three different dependent variables, more precisely, the intentions to boycott, participate in negative WOM, and protest behavior. PLS is a variance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) approach. It has several advantages over covariance-based SEM approaches such as LISREL (Henseler et al. 2009). In particular, formative constructs and moderation effects with metric variables can be included in the model. The finite-mixture (FIMIX) algorithm was applied before testing the hypotheses to ensure that no unobserved heterogeneity is present in the data (Hair et al. 2016). Considering the resulting low segment sizes (<10%), as well as inconsistent values of the fit indices (i.e., AIC, BIC, CAIC, and entropy), the FIMIX findings do not indicate unobserved heterogeneity.

Hypotheses testing were conducted using the SmartPLS 3.0 software (Ringle et al. 2015). Figure 2 gives an overview of the results of the PLS path analyses. In addition, “Appendix 2” gives more detailed information on for example, the path coefficients’ confidence intervals. The PLS analysis reveals that the coefficients of determination (R2) for boycott intention variance, intention to engage in negative WOM, and protest intention are 0.45, 0.47, and 0.46. This indicates good explanatory power for the model delineated. Hypothesis H1 assumes direct and positive effects of resistance motives on behavioral intentions. The study results confirm the hypothesis with regard to all types of active rebellion. Figure 2 reveals that the effect of motives is stronger for the intention to participate in negative WOM (0.51***) and to protest (0.60***) than for the intention to boycott (0.32***).Footnote 4 The PLS results also confirm hypothesis H2, and the negative direct effect of counterarguments is more pronounced for the intention to boycott (−0.31***) than it is for WOM intention (−0.17***) and for protest intention (−0.15***).Footnote 5 Idealism has significant positive direct effects on boycott and WOM intentions, as H3a hypothesizes. Contrary to this hypothesis, idealism does not impact the intention to protest. In contrast to hypothesis H3b, relativism does not affect WOM intention. Moreover, as Fig. 2 shows, the significant path coefficients of relativism on boycott and protest intentions have the opposite sign value than initially assumed.

Figure 2 reveals that the PLS analysis found no significant moderation effects of ethical ideologies with regard to WOM intention. Contrary to this finding, empirical analysis reveals significant moderation effects with regard to the other considered forms of consumer rebellion. Figure 3 illustrates these moderation effects to make their interpretation easier. With regard to boycotting behavior, hypothesis H4a1 is confirmed because idealism dampens the effect of resistance motives. In addition, as hypothesis H4b2 assumes, the empirical findings reveal a significant moderation effect of relativism on the relationship between counterarguments and boycott intention. Considering the moderation effects of ethical ideology on the relationship between participation motives and protest intention, the PLS results confirm hypotheses H4a1 and H4b1 on one hand. On the other hand, contrary to hypothesis H4a2, idealism strengthens the effects of counterarguments on protest intention.

The current study simplified Forsyth’s theory to a certain degree by not explicitly considering the possible interaction between the two ethical ideologies. More specifically, considering Forsyth’s methodological recommendations (Forsyth n.d.), the model was re-estimated by adding the interaction of idealism and relativism to the model depicted in Fig. 1. Considering the WOM and boycott models, these additional analyses did not lead to different results with regard to significant or non-significant direct and moderating effects, respectively. Moreover, we found no significant interaction effect of idealism and relativism. When considering protest behavior as a dependent variable, the analysis found that the direct effect of relativism is not significant anymore. In addition, the study reveals a significant interaction effect of idealism and relativism (t value = 1.84; p < 0.10). More precisely, as Fig. 4 shows, a crossover effect of ethical ideologies appeared. Considering Forsyth’s (1980) classification, absolutists (i.e., people who are high on idealism and low on relativism) as well as subjectivists (i.e., people who are low on idealism and high on relativism) are in favor of protesting. On the contrary, situationists (i.e., people who are high on idealism and high on relativism) and exceptionists (i.e., people who are low on idealism and relativism) are opposed to protesting.

5 Contributions to and implications for research

The empirical results of the present study can be summarized as follows. The study reveals that resistance motives, counterarguments, and ethical ideologies have a varying impact on individuals’ inclination to engage in different types of resistance. Specifically, on the one hand, resistance motives have a stronger effect on individuals’ inclination to engage in negative WOM and protest behaviors. On the other hand, counterarguments are more decisive for boycott intention. Moreover, idealism drives boycott behavior and negative WOM but does not have a significant effect on protesting behavior. Relativism has a significant and positive effect on boycott and protest intentions, contrary to common research findings. No moderation effects of ethical ideologies were found with regard to negative WOM intention. Considering boycott intention, idealism diminishes the effect of resistance motives. Moreover, relativism dampens the effect of counterarguments. Idealism attenuates the effect of motives on boycott and protest intention. Relativism boosts the effect of participation motives on protest intention. Finally, idealism strengthens the effect counterarguments on protest intention.

This study expands existing knowledge on three distinct forms of individual resistance against allegedly unethical corporate behavior. First, negative WOM and protest behavior are considered in addition to boycotting behavior as further forms of consumer resistance. In line with existing papers about the motivational basis of resistance against corporate misconduct (e.g., Sen et al. 2001; Klein et al. 2004), the present research provides more elaborate information on the varying effects of motivational and ideological constructs on individual inclination toward the considered types of resistance. Considering these insights, involved organizations (e.g., NGOs or boycotted companies) can tailor their campaign or crisis communication strategies to pursued behavior. Second, the study investigates the impact of the individuals’ ethical ideologies on the inclination toward active rebellion. Contrary to ethical judgment, ethical ideologies are relatively stable cognitions. Therefore, the study findings are useful for the development of segmentation and targeting strategies that considers individuals’ ethical position (cf. Al-Khatib et al. 2005). Third, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, the current study is the first investigation of the moderating effects of ethical ideologies on the relationship between motivational constructs and ethical intentions in a business context. More precisely, the study offers new insights into how idealism and relativism regulate the effects of motivational constructs on consumer behavior and, therefore, contributes to research on the ethical decision-making of an important stakeholder group of businesses.

The study results reveal that negative WOM behavior is driven by both motivational factors considered in the delineated model (i.e., counterarguments and motives). In particular, motives are important for individuals’ WOM engagement. First, WOM inclination can be considered to be driven by the perception that it is instrumental in achieving the goals pursued. Second, the effect found also indicates that consumers perceive negative WOM to be particularly suitable for expressing anger and feelings of frustration as well as benefiting from moral self-enhancement. This may be because WOM represents a form of individual voice behavior that allows making direct personal contact with other persons (Richins 1983). Contrary to boycott intention, the effect of counterarguments on WOM intention is less strong. This may be because negative WOM is not associated with constrained consumption, and free-riding incentives should thus be less-pronounced in this context, too. In addition, idealism has a moderately strong positive direct effect on individual WOM intention. This may be a result of negative WOM being a less-radical form of resistance than protesting; therefore, WOM fits the idealists’ value system better. Finally, ethical ideologies do not moderate the effects of both participation motivation and counterarguments on individuals’ negative WOM intention. The process of making the decision to engage in WOM is seemingly less complex than that underlying protesting and boycotting. This finding might be explained by WOM being a low-involvement and impulsive behavior, and the strong, direct effect of the participation motivation points in the same direction. Apparently, as Verhagen et al. (2013) show, individuals regard negative WOM as a means of instantly venting one’s own anger and frustration.

The findings reveal that all independent variables considered in the model have a significant effect on boycott intention. In particular, counterarguments have a pronounced significant direct and negative effect on consumers’ intention to boycott. Therefore, considering our twofold conceptualization of counterarguments, it can be assumed that perceptions of low substitutability of preferred products impede individuals from participating in boycott actions. This may be explained by the fact that boycotting factually requires cutting consumption or switching to less preferred products. In addition, boycotting is a form of collective action in which social-dilemma issues are highly salient (John and Klein 2003; Klein et al. 2004). Thus, free-riding incentives and the small-agent problem are particularly decisive here. Idealism has a direct and positive effect on boycott intention. Apparently, similar to negative WOM, idealistic citizens consider boycotting behavior a suitable instrument to change alleged unethical corporate behavior. This may be because boycotts and negative WOM aim to mitigate unethical corporate conduct, which is at the heart of the idealistic dogma (cf. Rawwas et al. 2004). Turning toward the moderating effects of ethical ideologies, first, relativism weakens the negative effect of counterarguments on boycott intention. The finding that arguments against boycott participation are less important for relativists is in line with this study’s notion that Machiavellian persons are to a greater extent motivated to remove obstructions that stand in the way of overcoming structures of power. Second, idealism attenuates the effect of resistance motivation on boycott intention. Since idealists do not have the tendency to be socially dominant (Wilson 2003), are oriented toward organizational control systems, and show little deviant behavior (Henle et al. 2005; Hastings and Finegan 2011; Park 2005), boycotting apparently opposes the idealistic inclination to subordinate themselves to authoritarian structures (McHoskey 1996). As idealists typically behave in accordance with moral absolutes (Lu and Lu 2010) and thus try to avoid potential damage to third parties (also including companies), exercising pressure on companies by means of consumer boycotts is in opposition to this idealistic stance.

The direct effect of relativism on protest intention as well as on boycott intention is significant and positive. Hence, considering these empirical findings, the assumed negative relationship between relativism and consumers’ tendency to engage in these forms of active rebellion has to be rejected. While the study findings on idealism fit the scientific literature, the positive effect of relativism is counterintuitive at first sight. One possible explanation could be that boycotting and protesting contain aspects that some people judge to be morally troublesome. More precisely, these types of resistance represent a rather aggressive means of retaliation. Hence, as relativism is found to be a determinant of unethical behavior (Rawwas and Isakson 2000), relativists are possibly more prone to return a wrong with a wrong and thus have a higher propensity to participate in these forms of resistance against alleged corporate misconduct. Moreover, consumers seem to have higher moral expectations of businesses than of themselves (Davis 1979; DePaulo 1986). As relativists reject universal moral rules (Forsyth 1980), this moral double standard might be more salient among relativists. When confronted with unethical business conduct, they could apply more rigorous standards than when confronted with their own responsibilities. Moreover, considering discourse ethics, relativism suggests that norms can only be generated in a free and open discourse (Habermas 1991). Against this, considering this study’s conceptualization of protest behavior, one could assume that by directly complaining to the company, signing petitions or participating in targeted actions or demonstrations, relativists try to enter a discourse with the affected company. Protest behavior is a means of publicly expressing disapproval and triggering a reaction from the affected corporation. Since relativism respects different microcosms having varied ethical views (Donaldson 1996), relativists assumingly respect involved companies and their divergent views more strongly. Hence, entering an active dialogue may be a logical consequence for them. Furthermore, three moderating effects on protest intention of the considered ethical ideologies were found. First, similar to boycott intention, idealism mitigates the impact of resistance motives. Hence, protest behavior seems to contradict their inclination to subdue to organizational or social rules. Second, idealism strengthens the negative effect of counterarguments on protest intention. Hence, it cannot be confirmed for idealists that counterarguments are weakened by reduced free-riding incentives, perceived lower small-agent problems, or an anti-materialistic orientation. Publicly denouncing affected companies, directly confronting them with severe accusations, and singing petitions will draw political institutions’ attention to the issue. Hence, affected companies have to reckon with image loss or regulatory sanctions. Since idealists believe that, when choosing the right action, desirable outcomes can always be obtained (Forsyth 1980), participation in protest movements can presumably not be considered to be the right option from an idealist’s perspective, and counterarguments are thus more decisive for the formation of idealists’ protesting intention than resistance motives. Third, as assumed, relativism strengthens the impact that resistance motivation has on protest inclination. Relativists are more responsive to peer behavior (Park 2005), and vice versa, this higher susceptibility to peer behavior might assumingly be associated with an illusion of control over others. In comparison to non-relativistic consumers, relativists believe more strongly that they can exert influence over their peers. This illusory feeling of control might have increased the inclination to engage in collective protest actions that is based on instrumental motivation. In addition, protest participation can be regarded as a vehicle for publicly demonstrating power over companies, and resistance motivation may thus have a stronger effect on relativists’ behavioral intention.

6 Implications for management

The results have practical implications for both NGOs campaigning against unethical corporate behavior and companies facing consumer resistance. The study suggests several ways in which resistance behavior could be stimulated by NGOs. These findings are of significant importance because NGOs commonly depend on donations (e.g., Schepers 2006) and are less able to fund their operations through market revenues. Therefore, NGOs typically have scarce resources (Froelich 1999) in comparison to for-profits. Hence, NGOs have to allocate their scarce resources carefully to maximize the benefit-cost ratio of their activities. When NGOs call for a product boycott, they should thus, in particular, try to reduce the perceived costs of participation because these costs are a more significant driver of boycott intention than of protest and WOM intention. To free the individual from doubts regarding adverse effects of boycotting, such as job cuts in the boycotted companies, they could get involved in the creation of alternative employment opportunities by, for example, cooperating with international labor organizations. To reduce small-agent perceptions, which represent a facet of the social-dilemma component of cost perceptions, NGOs could use communication strategies that emphasize the importance of individual action to enhance the consumer’s self-efficacy. For example, according to Nicholls (2002), the consideration of factual success stories appears to be instrumental in helping consumers to see that they can make a difference on the societal level with their decision to boycott an accused company. Furthermore, to attenuate the demotivating effects of the preference for the boycotted product, NGOs could inform consumers about ethical substitutes (e.g., reasonably priced fair-trade clothing as an alternative buying option for products from fast-fashion retailers). Considering the moderating effect of idealism on the relationship between motives and boycott intention, boycott sponsors should try to target individuals with a non-idealistic ethical orientation. The non-idealistic market segment is characterized by a higher proportion of males and younger people, according to Bass et al. (1998). Non-idealistic communication appeals could stress teleological or utilitarian ethical norms. Due to a less-pronounced effect of counterarguments, targeting relativists to increase boycott intention is advisable, too. Furthermore, NGOs should strive to activate instrumental motives (e.g., appeals that promise high expected participation) as well as non-instrumental motives (e.g., anger-arousing communication appeals) to motivate individuals to engage in negative WOM and protesting. Comparable to the targeting recommendations for boycott sponsors, NGOs that aim to motivate individuals to participate in protest campaigns should target the segment of relativists that consists of younger persons (Bass et al. 1998) because relativism has a significant direct effect on behavioral intention and boosts the effect of resistance motives.

For companies that have to address instances of consumer resistance, a change in corporate practices is not always possible, at least in the short term. For example, it does not seem plausible that manufacturers of allegedly unethical products can immediately change their methods of production or their portfolio of suppliers. Considering the case used in this study, sweets manufacturers are confronted with a distinct supply deficit even of conventionally produced cocoa (International Cocoa Organization 2016) that assumingly sets limits to an increase in the market share of fair-trade chocolate, too. Considering this limited space for manoeuver, the study provides recommendations for public relations measures and crisis communication. On the one hand, companies confronted with calls for a boycott of their products should strive to increase arguments against boycott participation because perceived participation costs are the most important determinant of boycotting behavior. First, stressing comparative advantages in the performance of the own products in comparison to possible substitutes may represent a way of making the product preference more salient. Second, emphasizing the adverse effects of a boycott on the company (e.g., loss of jobs) may reinforce the importance of the social-dilemma component of arguments against boycott participation. Considering the moderating effect of relativism on the relationship between counterarguments and boycott intention, boycotted companies should particularly target non-relativists because arguments against participation are more salient for these consumers. Non-relativistic appeals could stress that, for instance, the working conditions in developing countries have to be judged based on utilitarian reasoning (e.g., lower prices for consumers and income opportunities for the workers). Turning toward the prevention of negative WOM and protest behavior, on the other hand, companies should try to suppress resistance motivation. Considering the non-instrumental motive component, corporations should open direct channels of communication to annoyed customers (e.g., crisis hotlines) to achieve this goal. Instead of engaging in negative WOM, consumers could vent their anger and directly blame companies for morally reprehensible incidents. Considering protest intention, companies should in particular try to provide opportunities for relativists to enter a discourse about the ethical issue at hand. Possibly, individuals’ inclination toward protesting could thus be reduced. Moreover, companies should target the segment of idealists because idealism attenuates the effect of motives on protest intention.

7 Limitations and future research

The study results should be interpreted in light of their limitations. First, only behavioral intentions have been considered as dependent variables, and these action tendencies do not automatically translate into actual behavior. Second, the study results may be distorted due to the social desirability bias. Interviewees often overestimate their own intention to act morally (Zerbe and Paulhus 1987; Randall and Fernandes 1991). Hence, a closer examination of the social desirability bias is indispensable, especially in the area of business ethics and consumer behavior. Self-reported measures, which are usually considered in consumer surveys, are especially vulnerable to this effect, and this study thus tried to mitigate these biases (see Sect. 4.1). Third, it is necessary to take into account that allegations of child labor and inappropriate working conditions at West African cocoa plantations are quite specific research objects. The external validity of the current study might thus be limited.

This study offers several possibilities for future research. First, the conceptual framework could be enhanced by considering affective or involvement-related constructs. Second, actual engagement in consumer rebellion could be observed over a certain period of time. A longitudinal study could then provide insights into the relevance of motives over the course of time and enable the segmentation of consumers on the basis of the time and scope of their commitment. Moreover, longitudinal studies would be instrumental to capture sequential changes in behavioral intentions. In a preliminary step towards such longitudinal studies, we tested a direct-effects-only model that comprises all behavioral intentions. We assumed that boycott intention (WOM intention) is an antecedent of WOM intention and protest intention (protest intention). The found direct effects correspond to the results depicted above. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that boycott intention drives WOM intention, which subsequently affects protest intention. Boycott intention has no significant direct effect on protest intention. Therefore, it seems likely that boycott intention as a more “passive” form of resistance is a perquisite for negative WOM and protest intention as the most “active” form of resistance apparently relates only indirectly to boycotting behavior. Third, the delineated model could be tested under different contextual circumstances. For example, other instances of unethical corporate behavior such as the relocation of jobs abroad could be considered. Fourth, actual ethical evaluation of criticized business practices (e.g., measured using Reidenbach and Robin’s (1990) multidimensional ethics scale) could be introduced as a mediator between ethical ideology and behavioral intentions. Fifth, considering the present study’s results regarding the psychometric properties of the EPQ scale (see measurement section), future research could try to refine the original measurement scale to make it more applicable to business research contexts. Sixth, considering Fournier’s (1998) classification, future studies could use this paper’s model to explain other categories of consumer resistance such as avoidance and minimization behavior. It would be particularly interesting to analyze whether the sign value of relativism’s direct effect on behavioral intention changes when different forms of resistance are considered.

Notes

Firms can also serve as substitute targets in so-called secondary boycotts (Schrempf-Stirling et al. 2013). For example, Chinese nationalists called for a boycott of the French retail group Carrefour and the French luxury brand Louis Vuitton after activists advocating for Tibetan independence disturbed the 2008 Summer Olympics torch relay in Paris (Pál 2009).

A confirmatory factor analysis conducted with SPSS AMOS that considered one covariance between two error terms showed an acceptable global fit for the three dependent variables’ measurement models (χ2 = 123.30, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 3.08; Hoelter’s N = 217; GFI = 0.95; AGFI = 0.92; NFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.95; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.07).

The authors evaluated the quality of measurement considering a confirmatory factor analysis conducted with SPSS AMOS. The global fit for the refined measurement of ethical ideologies can be regarded good to very good (χ2 = 42.88, p < 0.05; χ2/df = 1.72; Hoelter’s N = 434; GFI = 0.98; AGFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.04).

In order to see whether the differences in path coefficients are significant, we performed a “virtual” multi-group analysis based on the Welch-Satterthwaite test (Chin 2000). Each of the tests considers our sample twice as virtual subgroups. The analysis revealed that the difference in consumer motives’ path coefficients between the boycott model and the WOM model is significant (t value = 2.687, df = 838, p < 0.01). The same holds true for the difference between the boycott model and the protest model (t value = 3.960, df = 838, p < 0.01).

The Welch–Satterthwaite test reveals significant differences in counterarguments’ path coefficients between the boycott model and the WOM model (t value = −2.263, df = 838, p < 0.05) as well as between the boycott model and the protest model (t-value = –1.980, df = 838, p < 0.05).

References

Alexandrov A, Lilly B, Babakus E (2013) The effects of social-and self-motives on the intentions to share positive and negative word of mouth. J Acad Market Sci 41(5):531–546

Al-Khatib JA, D’Auria Stanton A, Rawwas MYA (2005) Ethical segmentation of consumers in developing countries: a comparative analysis. Int Market Rev 22(2):225–246

Al-Khatib JA, Al-Habib MI, Bogari N, Salamah N (2016) The ethical profile of marketing negotiators. Bus Ethics Eur Rev 25(2):172–186