Abstract

The goal of this study was to assess the relationship between type and quality of housing and childhood asthma in an urban community with a wide gradient of racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and housing characteristics. A parent-report questionnaire was distributed in 26 randomly selected New York City public elementary schools. Type of housing was categorized using the participants’ addresses and the Building Information System, a publicly-accessible database from the New York City Department of Buildings. Type of housing was associated with childhood asthma with the highest prevalence of asthma found in public housing (21.8%). Residents of all types of private housing had lower odds of asthma than children living in public housing. After adjusting for individual- and community-level demographic and economic factors, the relationship between housing type and childhood asthma persisted, with residents of private family homes having the lowest odds of current asthma when compared to residents of public housing (odds ratio: 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.22, 1.21). Factors associated with housing quality explain some of the clustering of asthma in public housing. For example, the majority (68.7%) of public housing residents reported the presence of cockroaches, compared to 21% of residents of private houses. Reported cockroaches, rats, and water leaks were also independently associated with current asthma. These findings suggest differential exposure and asthma risk by urban housing type. Interventions aimed at reducing these disparities should consider multiple aspects of the home environment, especially those that are not directly controlled by residents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prior research suggests that differences in the built environment across neighborhoods can result in community-level disparities in children’s health.1 Although some contend that associations observed between geographic areas and health outcomes are due to demographic characteristics of residents in the area,2 others have concluded that there are features of the local social and physical environments that may promote or inhibit health, including characteristics of the indoor built environment such as housing type and quality.3–6

For example, public housing residents in urban communities have been hypothesized to have high asthma prevalence due to both individual risk factors and neighborhood-level risk factors. By design, public housing is for low-income residents, with set income limits for eligibility.7 , 8 Further, public housing developments are primarily located in poor neighborhoods.9 , 10 Public housing has been associated with poor health outcomes. In a community-level analysis within New York City, Corburn et al. found that neighborhoods with elevated asthma hospitalization rates had five times the number of public housing units as compared to neighborhoods without elevated asthma hospitalization rates.11 Specifically, 23% of the housing in the four ZIP codes with the highest asthma hospitalization rates were public housing, as compared with an average of 4.45% for the city overall.11 It is possible that any relationship between public housing and asthma may be confounded by the concentration of low-income residents who are more likely to have asthma.12 , 13 However, it is also possible that characteristics of the housing itself can be associated with asthma, indicating an environmental justice issue related to poor-quality housing.14 Because urban areas have many different types of housing, strongly associated with residents’ socioeconomic status, it is also possible that differences in quality of these housing types may contribute to asthma disparities observed within urban communities. The distinction of housing type in studies of health disparities is relatively untouched in the scientific literature and can provide a useful lens through which to evaluate environmental justice issues.15 , 16

Poor housing quality in urban neighborhoods has previously been linked to a variety of poor health outcomes.3 , 10 , 14 , 17–20 For example, older housing, and its associated peeling paint, is associated with higher blood lead levels in children.21 Unintentional injuries including falls, choking, poisoning, and burns are higher in homes with faulty construction or poor maintenance.1 Greater asthma morbidity, specifically a larger number of hospitalizations due to asthma, more frequent episodes of wheezing, and more frequent night symptoms due to asthma have been associated with the presence of moisture, mildew, and cockroach allergen in homes.22 , 23 The presence of these allergens may be more common in deteriorating housing, which is often marked by water leaks, holes that pests can pass through, poor ventilation, and peeling paint.

Rauh et al. found a significant association between degree of housing disrepair (determined by the number of total adverse indoor housing problems) and cockroach allergen and asthma, independent of household income and ethnicity.17 In the Healthy Public Housing Initiative, a community–academic partnership to improve health and housing conditions in Boston public housing, substandard public housing that was found to have holes in the wall/ceiling had increased concentrations of cockroach allergen compared to public housing without these problems.9 Because poor housing quality has been found to be associated with presence of indoor asthma triggers, it may be possible for health disparities to arise in certain types of housing where residents may lack the resources, both economic and political, to improve housing quality.24

The objective of this study was to compare the prevalence of asthma in a range of urban housing types and determine if the relationship between housing type and current asthma persists, after controlling for individual demographic risk factors, neighborhood income, and markers of housing quality. We hypothesize that asthma prevalence varies significantly across housing types, and that the relationship between housing type and current asthma is modified by markers of indoor housing quality. Asthma disparities due to housing type and quality result in environmental injustice for low-income residents, who often have little control over housing quality and maintenance.

Methods

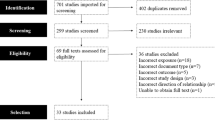

A parent-report, cross-sectional survey was conducted in randomly selected New York City public elementary schools to measure the prevalence of childhood asthma in different New York City communities.25 The project was reviewed and approved by the Mount Sinai Institutional Review Board, the Mount Sinai Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Office, and by the Proposal Review Committee of the New York City Department of Education’s (DOEs) Division of Assessment and Accountability.

Study Design

Methodology for selecting the participating schools has been published elsewhere.25 , 26 Briefly, schools were randomly selected for inclusion in the study based on the childhood asthma hospitalization rate in each neighborhood. Asthma hospitalization rates for children aged 5–12 were calculated for each of the residential ZIP codes in New York City, then ranked and grouped. In order to achieve a representative sample, schools from the ZIP codes within the highest, median, and lowest hospitalization groups were eligible for the study.

Using the SAS Surveyselect Procedure,27 one school was selected from each ZIP code, with a probability proportional to size. A total number of 26 schools were selected, eight from the high group, eight from the median group, and ten from the low group to compensate for the low asthma prevalence that was expected in those neighborhoods. At each school, two classrooms from each grade level, kindergarten through fifth grade and full-time special education classes, where available, were randomly selected to participate. Students were given questionnaires to be brought home to be completed by their parents or guardians. Children and teachers were given nominal incentives such as school supplies to encourage their participation.

Characterization of Housing Type

Participant addresses were collected on the questionnaire. In order to obtain information on building type, the addresses were imputed into the web-based application of the Buildings Information System (BIS) of the New York City Department of Buildings.28 The BIS is a publicly available database that is used by the Department of Buildings to collect information on properties throughout New York City, including property profiles, licenses, violation and complaint tracking, and construction permit applications.28 The BIS classifies buildings using the New York City Department of Finance occupancy codes, which separates all properties into over 200 distinct categories.29 The participant addresses in this study were classified into 47 of these categories. These were then collapsed into six major categories of residential housing. Any building that was designated as public was included in the category “All Public Housing”. Categories for private housing translated directly from the main categories in the BIS and included “Walk-Up Apartments”, “Elevator Apartments”, “Family Dwellings”, and “Mixed-Use Residence.” “Family Dwellings” included both single and multi-family stand-alone houses. The “Mixed-Use Residence Private” category included buildings that were primarily residential, but also had commercial uses. The “Other Private” category consisted of apartment buildings that did not fall into the major categories of housing listed above and included condominiums, store buildings, hotels, and other miscellaneous buildings that were not city owned (public).

Characterization of Demographic and Housing-Related Factors

The questionnaire was adapted from a previous study of asthma prevalence used in a New York City public elementary school.30 It contained standardized questions on demographics, household environment, and asthma symptoms from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC).31 The questionnaire was available in English, Spanish, and Chinese and was pilot-tested with native speakers prior to the start of the study to ensure clarity and accuracy.

A child was classified as having current asthma if a “yes” response was given to both of the following questions: “Have you or your child ever been told by a physician or a nurse that he or she has asthma?” and “In the past 12 months, has your child had wheezing in the chest?”

Housing characteristics were assessed using the following item on the survey instrument “In your home, do you have any of the following: throw rug, wall-to-wall carpet, air conditioner, air purifier, humidifier, gas cooking stove, water leaks, mold.” Water leaks can also be used as a proxy for mold, since resident-reported mold has been previously shown to have a low level of agreement with trained inspector assessments.32 In addition, the presence of pests was determined using the question: “In the past 2 weeks, have you seen any of the following in your home?: Rats, mice, cockroaches.” The presence of environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) was defined as “anyone who lives in the home or regularly visits who smokes any of the following: cigarettes, pipes, or cigars.”

Because the association between type of housing and current asthma could be confounded by the neighborhood in which the housing is located, data on ZIP code median household income was collected from the US Census and used as a proxy for neighborhood socioeconomic status. Each of the participants was assigned the ZIP code median household income for the ZIP Code of residence indicated on their questionnaire.

Data Analysis

The data were weighted to reflect Department of Education public elementary school enrollment data in each Zip Code. All analyses were conducted using SAS v9.1’s Survey Procedures, which account for the sampling design of stratification by neighborhood asthma rate, clustering by school, and unequal weighting.27 Population proportions of demographic characteristics and asthma prevalence by housing type were calculated using the Surveyfreq procedure. In order to determine if there was a relationship between housing type and current asthma, the Rao–Scott Chi-Square test statistic was utilized as a measure of association. The same procedure was used to examine current asthma in relation to housing characteristics.

Three regression models were constructed using the Surveylogistic procedure in order to examine the relationship between housing type and current asthma. Missing data were excluded from these analyses. The first model was unadjusted and included only the housing type and current asthma variables. The second model was adjusted for demographic variables which previous research suggests are associated with current asthma: ethnicity, income, and gender.12 , 26 The third, fully adjusted model, included the previously mentioned demographic variables, but also controlled for ZIP code median household income, a proxy measure of neighborhood SES, as well as housing quality factors reported by the respondents that remained independently associated with current asthma.

Results

Description of Study Population

Overall, 5,250 children returned a questionnaire, yielding an adjusted33 response rate of 76.9%. As shown in previous publications, this sample was highly comparable to the enrolled population of the selected schools, the 5–12-year-old population of the surrounding ZIP codes, and the overall New York City public elementary school population.26 Of these 5,250 children, 397 had missing housing data either because they did not provide a complete address (n = 364) or their address was unclassifiable by the BIS database (n = 33), leaving 4,853 children in our analysis. There was no difference in the demographic profile or asthma prevalence of children with housing data when compared to the full study population.

Demographic and Housing Characteristics by Type of Housing

More children lived in private walk-up apartments than any other housing category, with a weighted percentage of 40.7%. Private family dwelling/house was the second most common type of housing at 26.1%. Thirteen percent of children reported living in elevator buildings, and 11.3 % of the sample was classified as living in public housing. Slightly more than 3% of our sample had an address that was classified as a mixed-use building, while 5.4% lived in another form of housing. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, measured by the Census as median household income of all residents in a ZIP code, was lowest for residents of public housing at $27,609 and highest for residents of private family dwellings at $42,247. The remaining types of housing, mixed-use residences, walk-up apartments, elevator apartments, and other types of private housing, had similar neighborhood income levels ranging from $29,541 to $33,602, respectively.

The demographic profiles of the children living in the different types of housing are listed in Table 1. Minority children, especially African-Americans and Puerto Ricans, and children from low-income households made up greater proportions of public housing residents, while Whites, Asians, and children from more affluent families were more likely to live in private family dwellings than any other type of housing. Mexican made up 30% of the respondents who lived in mixed-use buildings, despite representing only 8.00% of the study population.

Markers of housing quality varied significantly by housing type. Residents of public housing were much more likely to report the presence of cockroaches than residents of family dwellings, (68.7% vs. 21%), and were less likely to report use of an air conditioner (50.6% vs. 75.1%). Mold and rats were more commonly reported by residents of mixed-use buildings, while over 41% of walk-up apartment residents reported mice.

Prevalence of Asthma by Type of Housing

Type of housing was significantly associated with the presence of current asthma, defined as physician-diagnosed asthma with wheezing in the previous 12 months (p < 0.0001). The prevalence of current asthma was highest among public housing residents (21.8%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 17.3–26.3; Figure 1). Asthma prevalence was similar in walk-up apartments, elevator apartments, mixed-use residences, and other private apartments ranging from 11.3% (95% CI, 9.32–16.9) in other private apartments to 13.1% (95% CI, 9.32-16.9) in walk-up apartments. Children living in private family dwellings had the lowest prevalence of current asthma (7.38%; 95% CI, 5.61–9.15).

Multivariate Analysis

In order to determine if demographic- and housing-related characteristics could explain the relationship between housing type and current asthma, three logistic regression models were created and the unadjusted, adjusted for demographics, and fully adjusted odds of current asthma by housing type were compared (Table 2). In the unadjusted analysis, children living in any form of private housing had lower odds of current asthma when compared to children living in public housing. Children living in private family dwelling had the lowest odds, as they were 0.29 times as likely as children living in public housing to have asthma. After adjusting for demographic factors such as race/ethnicity, income, and gender, children living in all private housing still had lower odds of current asthma than children living in public housing. However, the magnitude of the odds ratios moved closer to the null value of 1.0 and confidence intervals became wider. Children living in family dwellings had the lowest odds of current asthma (ORadj = 0.41, 95% CI, 0.17–0.96).

Adding housing-related factors and median neighborhood household income to the model, the odds of current asthma for residents of mixed-use apartments, other private apartments, and family dwellings, compared to public housing, again moved closer to the null with wider confidence intervals. However, the odds of current asthma for residents of walk-up and elevator apartments did not change after this final stage of adjustment, and the odds for elevator apartment residents remained significantly lower compared to public housing residents. After controlling for ethnicity, income, gender, housing type, and median neighborhood household income, several markers of housing quality were associated with current asthma. Children living in homes with reported water leaks were 1.54 times as likely to have current asthma as children living in homes without leaks (95% CI, 1.15–2.08). Living in a household with cockroaches or rats was also associated with having current asthma in the final adjusted model. The remaining indoor factors (throw rugs, wall-to-wall carpet, air conditioner, air purifier, humidifier, gas cooking stove, mold, and mice) were not associated with current asthma after adjustment and were not included in the final adjusted model.

Discussion

This study found a high prevalence of asthma in public housing, which is consistent with another study conducted in a New York City public housing population.34 Our study added to this work by systematically comparing asthma prevalence across a range of housing types and finding that children living in public housing have higher odds of asthma than children living in all types of private housing, even after adjusting for individual risk factors for asthma such as minority ethnicity/race, living in a low-income household, and living in a low-income community. This research validates a previous study, which posited that the high prevalence of asthma in low-income neighborhoods within New York City was due in part to the large concentration of public housing in these neighborhoods.11

Because of its ubiquity in the urban environment and government regulation, public housing is an important institution to examine, especially given the independent association with asthma morbidity presented here. Research shows that public housing is characterized by extremes of poverty and environmental triggers that exacerbate asthma.3 , 24 , 35 The median neighborhood income is lower for public housing compared to all types of private residences. Further, cockroaches and ETS are reported more often by residents in public housing compared to residents of any type of private housing. Additionally, having a low enough income to qualify for public housing may also indicate difficulties accessing medical care due to lack of financial resources. However, even after adjusting for individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) factors as well as presence of indoor triggers, the odds of current asthma remains higher in public than private housing.

Some of this difference may be explained by unmeasured housing characteristics, such as ventilation. Previous work has found that inadequate ventilation in public housing can contribute to elevated levels of indoor nitrogen dioxide, which can exacerbate asthma.36 Additionally, we found that public housing was much less likely to have air conditioners than private housing. This could mean that residents are more exposed to outdoor air, which in low-income, minority communities, is more likely to be polluted due to environmental injustices such as discriminatory public policies in land zoning that have placed more polluting facilities and truck routes in poor communities compared to wealthier communities.11 , 37–40

It is also possible that the social environment of public housing developments contributes to greater asthma morbidity. Previous research suggests that psychosocial stressors, such as exposure to violence, can increase a child’s susceptibility to asthma triggers, including indoor allergens and ambient air pollution.41–43 Vanderbilt et al. found that one-quarter of asthmatic children from a sample of patients at an inner-city asthma clinic had symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, and almost three-quarters had witnessed a traumatic event.44 An earlier study of quality of life among asthmatic children and their families living in Boston public housing developments found a strong association between fear of violence and the child’s respiratory symptom score.45

Because we examined an ethnically and economically diverse sample of urban children, our study was able to examine markers of housing quality across a range of housing types. Although children living in private housing had lower odds of asthma than children living in public housing, markers of deteriorated housing were reported in many forms of private housing. For example, mice and rats were most common in mixed-use apartments. This may be because some commercial establishments in mixed-use buildings attract such pests. Private family dwellings, where residents likely have more control over housing maintenance, had the lowest prevalence of all measures of deteriorating housing, except for water leaks, when compared to all other types of housing.

One potential explanation for this finding is that residents of apartments, who are less affluent and more likely to be of minority backgrounds than residents of private family dwellings, only have control over their own apartment and are dependent upon housing management to maintain structural and building-wide maintenance and quality, which in turn can affect their home environment.46 Previous research has found that industrial cleaning of individual apartments only transiently reduces cockroach and mouse antigen levels indicative of ineffective elimination.47 Researchers in New York City who conducted an apartment-level housing intervention aimed at reducing indoor allergens cited structural and/or building-wide characteristics, such as garbage in the common areas or rats in the basement, as major impediments to residents’ ability to sustain housing improvements.48 Similarly, the Seattle-King County Healthy Homes Project, which employed community health workers to perform home environmental assessments, found structural remediation necessary in order to reduce sources of exposure to asthma triggers in many participant homes.46 Results from studies such as these suggest the need for building-wide interventions and/or policy changes to improve overall housing quality. Jacobs et al. suggest that incorporating effective intervention activities into comprehensive building-wide policies and programs results in improvements in housing quality that can impact a number of different diseases and health outcomes, including asthma.49

In our study, housing characteristics, including the presence of cockroaches and water leaks, were not directly measured, but rather, reported by the study participants, introducing the possibility of recall bias. The BIS database did not contain a category for homeless shelters nor did our survey include an option for homeless; therefore, some parents who did not provide an address may not have had a stable residence. Our study did not assess the effects of homelessness, an extreme in the continuum of access to healthy housing; however, previous research has documented very high asthma prevalence among homeless children.50 One study found that children in families waiting for Section 8 public housing vouchers in Boston were exposed to more housing hazards and experienced health consequences as a result of poor housing conditions.51 The BIS also does not include information on whether the property is a rental or owner-occupied. This could also impact the amount of control the resident has over maintenance and housing quality.

Markers of housing deterioration were found in all types of housing and among residents with a wide range of socioeconomic levels. However, residents of private housing continued to have lower odds of current asthma than residents of public housing, after adjusting for individual risk factors for disease and markers of housing quality. This finding suggests that there may be other factors, both environmental and social, found in the public housing environment that contribute to urban health disparities in childhood asthma.

In conclusion, our study highlights important findings about the relationships between housing type and asthma. Markers of housing deterioration, most importantly roaches, rats, and water leaks, were found in all types of housing and among residents with a wide range of socioeconomic levels. While previous studies looked at public housing alone, the present study provides useful specificity about asthma morbidity by housing type. In regression analysis with multiple covariates, residents of public housing continued to have higher odds of current asthma than residents of private housing after adjusting for individual disease risk factors and markers of housing quality. This indicates that the convergence of various social, economic, or behavioral risk factors alone, as is often highlighted with public housing, does not adequately explain the burden experienced by public housing residents. We posit that lack of control of the maintenance of shared spaces in multi-unit dwellings, such as private apartment buildings and public housing developments, may contribute to the presence of asthma triggers and ultimately to the increased morbidity outlined in our findings.

Abbreviations

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ETS:

-

Environmental tobacco smoke

References

Cummins SK, Jackson RJ. The built environment and children’s health. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001; 48: 1241–1252.

Sloggett A, Joshi H. Higher mortality in deprived areas: community or personal disadvantage? BMJ. 1994; 309: 1470–1474.

Bashir SA. Home is where the harm is: inadequate housing as a public health crisis. Am J Public Health. 2002; 92: 733–738.

MacIntyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med. 2002; 55: 125–139.

Northridge ME, Sclar ED, Biswas P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. J Urban Health. 2003; 80: 556–568.

Vlahov D, Freudenberg N, Proietti F, et al. Urban as a determinant of health. J Urban Health. 2007; 84: 16–26.

New York City Housing Authority. Agency report 2003-2005. 2007:1. Available from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/downloads/pdf/agency_report_2003_2005.pdf. Accessed July 26, 2007.

New York City Housing Authority. About NYCHA: Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/nycha/html/about/factsheet.shtml. Accessed July 26, 2007.

Peters JL, Levy JI, Rogers CA, Burge HA, Spengler JD. Determinants of allergen concentrations in apartments of asthmatic children living in public housing. J Urban Health. 2007; 84: 185–197.

Hood E. Dwelling disparities: how poor housing leads to poor health. Environ Health Perspect. 2005; 113: A 310–A 317.

Corburn J, Osleeb J, Porter M. Urban asthma and the neighbourhood environment in New York city. Health Place. 2006; 12: 167–179.

Litonjua AA, Carey VJ, Weiss ST, Gold DR. Race, socioeconomic factors, and area of residence are associated with asthma prevalence. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1999; 28: 394–401.

Smith LA, Hatcher-Ross JL, Wertheimer R, Kahn RS. Rethinking race/ethnicity, income, and childhood asthma: racial, ethnic disparities concentrated among the very poor. Public Health Rep. 2005; 120: 109–116.

Rauh VA, Landrigan PJ, Claudio L. Housing and health: intersection of poverty and environmental exposures. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008; 1136: 276–288.

Evans GW. The built environment and mental health. J Urban Health. 2003; 80: 536–555.

McCarthy P, Byrne D, Harrison S, Keithley J. Housing type, housing location, and mental health. Soc Psychiatry. 1985; 20: 125–130.

Rauh VA, Chew GR, Garfinkel RS. Deteriorated housing contributes to high cockroach allergen levels in inner-city households. Environ Health Perspect. 2002; 110(Suppl 2): 323–327.

Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE III. What's housing got to do with it? Am J Public Health. 2000; 90: 183–184.

Matte TD, Jacobs DE. Housing and health—current issues and implications for research and programs. J Urban Health. 2000; 77: 7–25.

Srinivasan S, O'Fallon LR, Dearry A. Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. Am J Public Health. 2003; 93: 1446–1450.

Centers for disease control and prevention. Blood lead levels—United States, 1999–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005; 54: 513–516.

Belanger K, Beckett W, Triche E, et al. Symptoms of wheeze and persistent cough in the first year of life: associations with indoor allergens, air contaminants, and maternal history of asthma. Am J Epidemiol. 2003; 158: 195–202.

Bonner S, Matte TD, Fagan J, Andreopoulos E, Evans D. Self-reported moisture or mildew in the homes of head start children with asthma is associated with greater asthma morbidity. J Urban Health. 2006; 83: 129–137.

Krieger JW, Song L, Takaro TK, Stout J. Asthma and the home environment of low-income urban children: preliminary findings from the Seattle-King County Healthy Homes project. J Urban Health. 2000; 77: 50–67.

Claudio L, Stingone JA, Godbold J. Prevalence of childhood asthma in urban communities: the impact of ethnicity and income. Ann Epidemiol. 2006; 16: 332–340.

Claudio L, Stingone JA. Improving sampling and response rates in school-based research through participatory methods. J Sch Health. 2008; 78: 445–451.

SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT 9.1User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2004.

New York City Department of Buildings. The Business Information System. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dob/html/bis/bis.shtml. Accessed September 1, 2006.

New York City Building Classification System. Available at: http://nycserv.nyc.gov/nycproperty/help/hlpbldgcode.html. Accessed May 6, 2009.

Diaz T, Sturm T, Matte T, et al. Medication use among children with asthma in East Harlem. Pediatrics. 2000; 105: 1188–1193.

Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, et al. International study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995; 8: 483–491.

Engman LH, Bornehag CG, Sundell J. How valid are parents' questionnaire responses regarding building characteristics, mouldy odour, and signs of moisture problems in Swedish homes? Scand J Public Health. 2007; 35: 125–132.

Clark NM, Brown R, Joseph CL, et al. Issues in identifying asthma and estimating prevalence in an urban school population. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002; 55: 870–881.

Chew GL, Carlton EJ, Kass D, et al. Determinants of cockroach and mouse exposure and associations with asthma in families and elderly individuals living in New York City public housing. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006; 97: 502–513.

Hynes HP, Brugge D, Watts J, Lally J. Public health and the physical environment in Boston public housing: a community-based survey and action agenda. Planning Pract Res. 2000; 15: 31–49.

Zota A, Adamkiewicz G, Levy JI, Spengler J. Ventilation in public housing: implications for indoor nitrogen dioxide concentrations. Indoor Air. 2005; 15: 393–401.

Maantay J. Zoning, equity, and public health. Am J Public Health. 2001; 91: 1033–1041.

Link BG, Phelan JC. McKeown and the idea that social conditions are fundamental causes of disease. Am J Public Health. 2002; 92: 730–732.

Evans GW, Kantrowitz E. Socioeconomic status and health: the potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annu Rev Public Health. 2002; 23: 303–331.

Chakroborty J, Zandbergen PA. Children at risk: measuring racial/ethnic disparities in potential exposure to air pollution at school and home. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007; 61: 1074–1079.

Sandel M, Wright RJ. When home is where the stress is: expanding the dimensions of housing that influence asthma morbidity. Arch Dis Child. 2006; 91: 942–948.

Oh YM, Kim YS, Yoo SH, Kim SK, Kim DS. Association between stress and asthma symptoms: a population-based study. Respirology. 2004; 9: 363–368.

Clougherty JE, Levy JI, Kubzansky LD, et al. Synergistic effects of traffic-related air pollution and exposure to violence on urban asthma etiology. Environ Health Perspect. 2007; 115: 1140–1146.

Vanderbilt D, Young R, MacDonald HZ, Grant-Knight W, Saxe G, Zuckerman B. Asthma severity and PTSD symptoms among inner city children: a pilot study. J Trauma Dissociation. 2008; 9: 191–207.

Levy JI, Welker-Hood L, Clougherty JE, Dodson RE, Steinbach S, Hynes HP. Lung function, asthma symptoms, and quality of life for children in public housing in Boston; a case-series analysis. Environ Health. 2004; 3: 13–25.

Krieger JW, Higgins DL. Housing and health: time again for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2002; 92: 758–768.

Brugge D, Vallarino J, Ascolillo L, Osgood ND, Steinbach S, Spengler J. Comparison of multiple environmental factors for asthmatic children in public housing. Indoor Air. 2003; 13: 18–27.

Kinney PL, Northridge ME, Chew GL, et al. On the front lines: an environmental asthma intervention in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2002; 92: 24–26.

Jacobs DE, Kelly T, Sobolewski J. Linking public health, housing, and indoor environmental policy: successes and challenges at local and federal agencies in the United States. Environ Health Perspect. 2007; 115: 976–982.

Grant R, Bowen S, McLean DE, Berman D, Redlener K, Redlener I. Asthma among homeless children in New York City: an update. Am J Public Health. 2007; 97: 448–450.

Sharfstein J, Sandel M, Kahn R, Bauchner H. Is child health at risk while families wait for housing vouchers? Am J Public Health. 2001; 91: 1191–1192.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to the Mount Sinai Center for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention (NIEHS/EPA Children’s Center grants ES09584 and R827039, ES/CA12770) and by the NIEHS Short-term Training Programs (ES007298 and 5 T35 ES007269-19). Additional support was provided by the Environmental Justice and Healthy Communities Program of the Ford Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Northridge, J., Ramirez, O.F., Stingone, J.A. et al. The Role of Housing Type and Housing Quality in Urban Children with Asthma. J Urban Health 87, 211–224 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-009-9404-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-009-9404-1