Abstract

Background

Ceritinib is a potent selective ALK inhibitor with a manageable safety profile. In anecdotal reports, ceritinib was associated with organizing pneumonia (OP), which could be confused with disease progression.

Objective

We aimed to delineate the characteristics of OP that occurs during treatment with ceritinib, and evaluate its clinical implications.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 44 lung cancer patients whose tumors harbored ALK or ROS1 fusions and who had received ceritinib. OP diagnosis was based on radiographic and clinical features. Four OP cases were pathologically confirmed.

Results

Among 44 patients, 22 OP events occurred in 16 (36.4%) patients. The median time to the first event was 17.2 weeks (range 6.7–68.7 weeks). All events were grade 1 or 2. Radiographic features were categorized into four patterns: nodular (54.6%), consolidation (27.3%), parenchymal band (4.5%), and ground-glass opacity (GGO) (13.6%). OP improved in 20 events with drug interruption or corticosteroids. The median duration of OP was 11.3 weeks (range 2–24 weeks). Tumor response rate was 75% in OP-positive and 42.9% in OP-negative groups. The median progression-free survival was 16.7 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 10.1–not applicable (NA)] in OP-positive and 5.4 months (95% CI 3.6–8.4) in OP-negative patients (P = 0.004). The median overall survival was 46.2 months (95% CI 38.1–NA) in OP-positive and 10.5 months (95% CI 6.2–18.9) in OP-negative patients (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

OP occurs frequently during ceritinib treatment and must be distinguished from disease progression. OP could be reversible without fatal complications and its occurrence is associated with better survival outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Organizing pneumonia (OP) occurs frequently during ceritinib treatment of ALK- or ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. |

OP is reversible without fatal complications. |

Occurrence of OP is associated with improved survival outcomes. |

1 Introduction

Organizing pneumonia (OP) is an interstitial lung disease (ILD) with variable histopathologic features that presents in different radiographic patterns [1, 2]. Typical histopathologic features of OP include proliferation of granulation tissue involving distal bronchioles, alveolar ducts, and alveoli. Associated radiographic patterns on computed tomography (CT) images can include various findings, such as patchy consolidation, ground-glass opacities (GGOs), small nodular opacities, and bronchial wall thickening. Although the exact pathogenic mechanisms of OP are unknown, it is thought to be associated with alveolar epithelial injury and repair processes. Clinically, OP etiology may be related to various drugs, infectious conditions, or connective tissue diseases, or it may be idiopathic [2, 3].

OP has recently been reported in patients treated for non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), especially those who were treated with molecularly targeted agents. For example, transient asymptomatic pulmonary opacities (TAPOs) were observed in patients treated with osimertinib, a third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) [4, 5]. Researchers found that radiographic patterns of TAPO included GGOs and/or nodular consolidations that were highly suggestive of OP. TAPO is observed at a 20–35% frequency in patients treated with osimertinib. Notably, these lesions must be distinguished from NSCLC progression because TAPO lesions spontaneously resolve and mostly do not lead to fatal outcomes. TAPO occurrence was not associated with altered prognosis, and most cases resolved even without drug cessation [4, 5].

Ceritinib is a selective and potent TKI that targets gene rearrangements in anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) or ROS proto-oncogene 1 (ROS1). The drug was validated in phase III clinical trials as an effective therapeutic option for ALK-rearranged stage IIIB/IV NSCLC patients, either as a first-line therapy or a secondary treatment after failed crizotinib treatment [6, 7]. Ceritinib was also effective in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC and had profound durable responses in a phase II study [8]. Safety profiles showed that the most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events were increased concentrations of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), or gamma-glutamyltransferase (γ-GTP) levels. Gastrointestinal adverse events including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea were also reported at a high frequency with the initial dose of 750 mg per day given in a fasted state. Currently, the dose of 450 mg daily with food is now recommended, based on a phase I study demonstrating consistent efficacy and less gastrointestinal toxicity [9]. ILD or pneumonitis of any grades were reported in 1–2% of patients in the three major trials of ceritinib [6, 7, 10]. However, ILD-like lesions mimicking disease progression are reported in patients treated with ceritinib, which were later resolved with drug cessation and steroid treatments. Lim et al. [11] reported a case of OP in a patient with ALK-rearranged metastatic NSCLC who was treated with ceritinib; the OP was histologically confirmed and found to be resolved in subsequent CT images. Bender et al. reported an ILD case that developed during ceritinib treatment and presented as GGOs in CT images. Bronchioloalveolar lavage (BAL) revealed lympho-dominant patterns of leukocytes and negative microorganism cultures. These GGO lesions resolved after drug cessation and corticosteroid treatment [12]. Pellegrino and Facchinetti et al. also reported a patient case in which pulmonary consolidations sequentially occurred as a manifestation of drug toxicity to three types of ALK-inhibitors: brigatinib, ceritinib, and lorlatinib [13, 14]. Lung lesions that occurred during ceritinib were confirmed as acute fibrinous pneumonia in a tissue biopsy, and later resolved with drug withdrawal and steroid treatment [13]. The lung lesion that occurred with lorlatinib was initially misdiagnosed with disease progression, but was later confirmed to be a sarcoid-like reaction in surgical pathology [14].

Consistent with these cases, our clinical experience showed that a significant portion of patients treated with ceritinib developed new lung lesions during treatment and these lesions resembled OP in CT images. Importantly, the lesions have to be assessed with caution because disease progression is always a candidate during differential diagnoses. Clinically, these patients had various mild and uncharacteristic symptoms, and most of the lesions resolved with either transient drug interruption and/or corticosteroid treatments. Additionally, ceritinib rechallenge did not cause any fatalities, but led to a durable clinical response in many patients. Thus, in this study, we aimed to delineate the incidence, radiographic features, and clinical implications of OP that develop during ceritinib treatment in ALK- or ROS1-rearranged NSCLC patients.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Patients

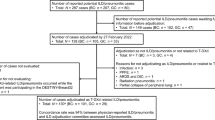

Using pharmacy disposition records, we identified 44 patients who were treated with ceritinib from January 2015 to August 2017 at the National Cancer Center (Goyang, Republic of Korea). All patients were diagnosed with NSCLC that harbored either ALK or ROS1 gene rearrangements and had been previously treated with crizotinib. In some patients, cytotoxic chemotherapy was also given either before or after treatment failure to crizotinib. Immune checkpoint inhibitors were not given in any patient as previous-line therapies. Ceritinib was given at an initial dose of 750 mg/day orally. Doses were reduced by 150 mg/day according to the physician’s decision to the lowest dose of 450 mg/day. Tumor assessments were performed every 6 weeks, based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 [15]. Data were collected by reviewing electronic medical records and CT images. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Cancer Center (IRB number; NCC2019-0239).

2.2 Organizing Pneumonia Diagnosis

The OP diagnosis was primarily based on chest CT images and clinical findings. Serial CT images taken during ceritinib treatment were reviewed by a thoracic radiologist (H. Lim, with more than 10 years of experience). Suspected cases of OP, based on either clinical or radiological findings, were thoroughly discussed and diagnosis was confirmed when the oncologist and radiologist reached a consensus. The patterns of OP were classified into four types based on radiologic features: nodular, consolidation, parenchymal band, and GGO [16].

2.3 Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.5.1). Descriptive statistics are reported as numbers and percentages of patients. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test, and categorical variables were compared using the Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test. Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariable analyses were performed using the Cox regression method. Selection of covariates for inclusion in multivariable models was based on a P-value of 0.2 or less in univariable analyses. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3 Results

3.1 Clinical Characteristics

In total, 44 patients with NSCLC with either ALK or ROS1 rearrangements were treated with ceritinib. All patients were previously treated with crizotinib, and ceritinib was a subsequent-line option. The data cut-off was 15 June 2020 and the median follow-up period was 12.9 months (range 0.4–64.6 months). OP was diagnosed in 16 patients (36.4%, referred to as OP-positive), and was not observed in 28 patients (63.6%, referred to as OP-negative) (Table 1). The median age for starting ceritinib treatment was 52.5 years (range 30–65 years) in the OP-positive group and 57.0 years (range 34–74 years) in the OP-negative group (P = 0.035). The two groups had no significant differences in other clinical characteristics, including sex, smoking history, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), number of prior therapies, and history of thoracic radiotherapies. One patient in the OP-positive group was treated with ceritinib for ROS1-rearrangement and the rest of the patients had ALK-rearrangements. No patient had underlying ILD, pneumonia, or other types of inflammatory conditions before ceritinib treatment. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) before starting ceritinib was also comparable between the two groups.

3.2 Characteristics of Organizing Pneumonia

Twenty-two OP events occurred in 16 patients. The average number of events per patient was 1.38 (range 1–3), with 11 patients having single events, four patients two events, and one patient three events (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1, see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM]). Median time to first OP event was 17.2 weeks (range 6.7–68.7 weeks). Ceritinib doses at OP onset varied. A full dose (750 mg/day) of ceritinib was given in six cases, 600 mg/day in eight cases, and 450 mg/day in eight cases (Table 2). Radiographic features of OP were categorized into four patterns (Table 2 and Fig. 1). There were 12 cases (54.6%) with a nodular pattern (Fig. 1a), six cases (27.3%) with consolidation (Fig. 1b), one case (4.5%) with a parenchymal band (Fig. 1c), and three cases (13.6%) with mixed GGO and nodular patterns (Fig. 1d).

Radiographic patterns of organizing pneumonia (OP). Representative chest CT patterns at OP onset and after improvement. a, b Nodular pattern (patient 13), c, d consolidation (patient 28), e, f parenchymal band (patient 10), and g, h ground-glass opacity (patient 30). Arrows indicate representative findings for each radiographic pattern

Tissue biopsies were performed in four patients. One patient underwent surgical resection (patient 23, Fig. 2a), one had a percutaneous needle biopsy (patient 31, Fig. 2b), and two had percutaneous needle aspirations (patients 13 and 28). Histopathology of the surgically biopsied sample revealed an exudate of fibrin that was converting to fibromyxoid masses rich in macrophages and fibroblasts (Fig. 2c). The tissue sample from the needle biopsy also had fibroblastic proliferation with mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and necrotic debris (Fig. 2d). These findings were consistent with the hallmark pathologic features of OP. Notably, no tumor cells were observed in any of the four biopsy specimens.

Organizing pneumonia (OP) confirmed with histopathology. a, b Chest CT images of OP. a Consolidation pattern of OP (patient 23) was noted, and surgical wedge resection was performed. b Nodular pattern (patient 31) of OP was noted, and percutaneous needle biopsy was performed. c, d Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of biopsy samples. c Histopathology of surgical biopsy sample revealed fibrinous exudate and fibromyxoid mass rich in macrophage and fibroblasts, consistent with advanced OP with multiple micro-abscesses (× 100 magnification). d Histopathology of needle biopsy sample revealed fibroblastic proliferation with mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and necrotic debris, which was also consistent with OP (× 200 magnification)

At OP onset, patients reported various symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, cough, dyspnea, chest wall pain, back pain, headache, fatigue, or pain in extremities (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM). There were no grade 3 or 4 adverse events, according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). All cases with dyspnea were grade 1 or 2 and did not require additional oxygen supplementation. No patient reported fever or productive cough that would suggest underlying infectious conditions. For laboratory tests, white blood cell counts (reference range 4000–10,000/μL) were decreased (leukopenia) in two cases, were within the normal range in ten cases, and were increased (leukocytosis) in ten cases. All patients with leukocytosis had a neutrophil-dominant pattern, with neutrophil fractions ranging from 70 to 93%. Eosinophil counts were mostly normal except for one patient who had eosinophilia (eosinophil fraction 12%) at OP onset. Serum AST (reference range 0–40 IU/L) and ALT (reference range 0–40 IU/L) levels were normal in seven cases, mildly increased (< 3 × upper limit of normal) in nine cases (40.9%), and highly elevated (≥ 3 × upper limit of normal) in six cases (27.3%) (Supplementary Table 1, see ESM).

3.3 Management of Organizing Pneumonia

For OP management, ceritinib was withheld in 18 cases. It was temporarily held in ten cases, and permanently withdrawn in eight cases. Ceritinib was stopped without other managements in 14 cases, and corticosteroids were given along with drug interruption in four cases. In one case, corticosteroids were given without drug cessation, and in two cases ceritinib was continued without interruptions or corticosteroid treatment (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3, see ESM). OP lesions were followed up with serial CT images, and radiographic improvement was confirmed in 20 cases. The median duration of OP was 11.3 weeks (range 2–24 weeks) (Supplementary Table 2, see ESM). Two cases did not improve. In one case, the patient was transferred to another hospital immediately after OP onset and was lost to follow-up (patient 4). For the other case, ceritinib use was discontinued at OP onset, but the patient died from a rapidly progressing brain metastasis and was not evaluated for lung lesions (patient 11).

Among 16 patients with OP, ceritinib was re-administered to nine patients after OP lesions improved (Supplementary Fig. 1, see ESM). Four of these had subsequent OP events. In three patients, the radiographic patterns of second or third OP events were similar to the initial OP event. However, in one patient (patient 23), the initial CT finding of a consolidation pattern changed to a nodular pattern in the second event. Nevertheless, clinical signs and symptoms were similar to initial events and there were no fatal complications even with rechallenge of ceritinib.

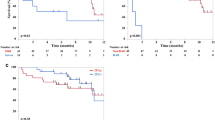

3.4 Clinical Responses to Ceritinib

We compared clinical responses to ceritinib between OP-positive and OP-negative groups. Duration of ceritinib treatment was significantly longer (median duration 10.5 vs. 3.9 months) in the OP-positive group (Supplementary Table 4, see ESM). In the OP-positive group, 12 patients (75.0%) had partial response (PR) and four patients (25.0%) had stable disease (SD). No OP-positive patient experienced complete remission (CR) or progressive disease (PD) as the best response. In the OP-negative group, 12 patients (42.9%) had PR, six patients (21.4%) had SD, and ten patients had PD (35.7%). Both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were significantly longer in the OP-positive group. Median PFS was 16.7 months (95% CI 10.1–NA) in the OP-positive group and 5.4 months (95% CI 3.6–8.4) in the OP-negative group (P = 0.004) (Fig. 3a). Median OS was 46.2 months (95% CI 38.1–NA) in the OP-positive group and 10.5 months (95% CI 6.2–18.9) in the OP-negative group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3b). Therapeutic strategies for ROS1-positive NSCLC differ from ALK-positive disease in terms of TKIs available for treatment. Therefore, we performed the survival analyses only in ALK-positive patients (n = 43). Results of PFS and OS were similar to the data from all patients (Supplementary Table 5, see ESM). Median PFS was 16.7 months (95% CI 10.2–NA) in the OP-positive group and 5.4 months (95% CI 3.6–8.4) in the OP-negative group (P = 0.002) (Supplementary Fig. 2a, see ESM). Median OS was 46.2 months (95% CI 38.1–NA) in the OP-positive group and 10.5 months (95% CI 6.2–18.9) in the OP-negative group (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2b, see ESM).

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) stratified by the occurrence of organizing pneumonia (OP). a Kaplan–Meier plot of PFS in OP-negative and OP-positive groups. The median PFS was 5.4 months in the OP-negative group and 16.7 months in the OP-positive group (Log-rank test, P = 0.004). b Kaplan–Meier plot of OS in OP-negative and OP-positive groups. The median OS was 10.5 months in the OP-negative group and 46.2 months in the OP-positive group (Log-rank test, P < 0.001)

The OP-negative group included patients who were treated with ceritinib for a very short period of time, which may have confounded the clinical response and survival comparisons between the two groups. Therefore, we only compared clinical responses in patients who were treated with ceritinib for at least 8 weeks. After excluding patients with short treatment durations, there were 32 patients (13 OP-positive and 19 OP-negative) (Supplementary Table 6, see ESM). The duration of ceritinib treatment was still significantly longer in the OP-positive group (median duration: 16.7 vs. 5.5 months, P = 0.030). The overall response rate was 92.3% in the OP-positive group and 63.2% in the OP-negative group. PFS and OS were both significantly longer in the OP-positive group, which is consistent with the analyses from all patients. Median PFS was 16.8 months (95% CI 10.2–NA) in the OP-positive group and 7.6 months (95% CI 5.4–18.2 months) in the OP-negative group (P = 0.025) (Fig. 4a). Median OS was not reached in the OP-positive group and was 13.7 months (95% CI 10.4–NA) in the OP-negative group (P = 0.007) (Fig. 4b).

Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) stratified by the occurrence of organizing pneumonia (OP) in patients treated with ceritinib for at least 8 weeks. a Kaplan–Meier plot of PFS in OP-negative and OP-positive groups. The median PFS was 7.6 months in the OP-negative group and 16.8 months in the OP-positive group (Log-rank test, P = 0.025). b Kaplan–Meier plot of OS in OP-negative and OP-positive groups. The median OS was 13.7 months in the OP-negative group and was not reached in the OP-positive group (Log-rank test, P = 0.007)

3.5 Organizing Pneumonia as an Independent Predictive Factor of Clinical Outcome

To assess whether OP occurrence was a predictive factor for a better clinical outcome after ceritinib treatment, we analyzed various clinical characteristics associated with survival. In multivariable analysis, we found that male sex (male, hazard ratio [HR] 0.37, 95% CI 0.16–0.81), having only one previous therapy event (one previous therapy, HR 0.21, 95% CI 0.07–0.59), and OP occurrence (OP-positive, HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.19–0.94) were significantly associated with a better PFS outcome (Supplementary Table 7, see ESM). For OS, good performance status (PS: 0 or 1, HR 0.26, 95% CI 0.11–0.58), lower NLR (NLR < 3, HR 0.26, 95% CI 0.10–0.67), and OP occurrence (OP-positive, HR 0.14, 95% CI 0.04–0.42) were significantly associated with a better outcome (Supplementary Table 8, see ESM). Among these factors, OP occurrence was the only factor associated with better outcomes for both PFS and OS.

4 Discussion

Disease progression is always considered first during differential diagnoses when newly developed lung lesions occur during NSCLC treatment. Because disease progression means that the anticancer agent is no longer effective, the ongoing cancer treatment is then terminated, and other therapeutic options are discussed. In this respect, it is critical to accurately diagnose OP in patients treated with ceritinib because OP must be distinguished from disease progression. In this study, we found that OP occurs frequently in lung cancer patients treated with ceritinib (16 of 44 patients, 36.4%). We classified the radiographic patterns of OP into four categories (nodular, consolidation, parenchymal band, and GGO) and noted that GGOs always co-occurred with nodular patterns. Unlike typical drug-induced ILD, these lesions were non-fatal, reversible, and did not require permanent ceritinib cessation. In a clinical trial for ceritinib, ILD incidence was 4% (nine of 246 patients) and most cases (eight of nine) presented as CTCAE grade 3 or 4 [10]. However, we found no cases that were grade 3 or higher in our study of patients diagnosed with OP, and most of these cases resolved with either drug interruption or corticosteroids. Most importantly, rechallenge with ceritinib did not cause any fatal events and was associated with better clinical outcomes.

Clinical manifestations of OP in this study were atypical. Patients had various nonspecific symptoms, but most of these were mild, with CTCAE grade 1 or 2. AST and ALT levels were elevated in 68.2% of cases, but there was no evidence of eosinophilia to suggest drug hypersensitivity. Doses of ceritinib taken before OP occurrence also varied. Altogether, the atypical symptoms and laboratory test results suggest that OP does not have a pathognomonic sign that can aid diagnosis but should be clinically considered in patients presenting with CT findings similar to the radiographic patterns we observed in patients during ceritinib treatment. For suspicious cases, a strategic option could be to transiently withhold ceritinib and carefully monitor tumors for disease progression. In uncertain cases, a tissue biopsy could aid in diagnosis. Four patients in our study underwent biopsies and the histopathology findings were compatible with OP, showing fibro-inflammatory lesions with no evidence of tumor cells.

Our multivariable analyses confirmed that OP occurrence was an independent prognostic factor for both PFS and OS. Nevertheless, the finding of prolonged survival of the OP-positive group might have been caused by a longer treatment duration, rather than an improved clinical response. To validate our finding that better prognosis in OP is due to a better clinical response to ceritinib, we filtered out patients who were treated with ceritinib for less than 8 weeks and still found that both PFS and OS were significantly longer in the OP-positive group.

Other factors were also associated with better outcomes. Male sex and only having one previous line of therapy were highly associated with better PFS. Good performance status (ECOG 0 or 1) and a low NLR (< 3) were positively associated with longer OS. For the number of previous therapies, we consider one previous therapy to mean that the patient had been treated with only crizotinib before starting ceritinib, and two or more previous therapies to mean that the patient underwent additional cytotoxic chemotherapy either before or after crizotinib. The number of previous therapies was relevant to PFS, but not to OS. Many patients whose disease did not respond to ceritinib treatment were subsequently treated with other ALK inhibitors, such as alectinib or lorlatinib, and the use of these agents may have affected their long-term prognoses, potentially explaining why the number of previous therapies was not significantly associated with OS [17, 18]. NLR is a predictive marker for response in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors [19, 20]. Although NLR was not associated with PFS, we found that low NLR (< 3) was significantly associated with better OS. This finding implies that immunologic factors may also be relevant to clinical outcomes in patients with ALK- or ROS1-rearranged lung cancer who were treated with ceritinib. The precise pathogenic mechanisms of OP remain unknown, but are thought to be initiated by alveolar epithelial injury [3]. Subsequent inflammatory reactions and tissue repair processes lead to OP characterized by histopathologic and radiographic features. Four cases that were biopsied in this study also showed signs of inflammation and fibrotic changes, implying that OP is a phenotypical immune response induced by ceritinib. It is unknown whether the findings of inflammation and fibrotic changes are directly related to ALK inhibition. However, reports have shown that pulmonary toxicities occur with all types of ALK inhibitors. During the early clinical development of brigatinib, there was a subset of pulmonary events that occurred within 7 days of treatment initiation in 8% (11 of 137) of patients [21]. Also, a recent study reported that ALK inhibitor-related pneumonitis occurs in about 4.4% (11 of 250) of patients treated with crizotinib, ceritinib, or alectinib, with the most common CT pattern being OP (seven of 11 cases) [22]. Interestingly, four of these cases were related to ceritinib, with all patients presenting with CTCAE grade 1 or 2 toxicities. Because OP incidence in all patients treated with ALK inhibitors was lower than in our patient population, it seems possible that OP could commonly occur with all ALK inhibitors but be more prone to develop in patients treated with ceritinib.

Our study has several limitations. First of all, the diagnosis of OP mostly relied on clinical decisions, and only four patients had pathologic confirmation. Along with the radiologic findings and laboratory test results, infectious conditions should also be one of the primary differential diagnoses. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) or sputum cultures could have aided the diagnosis but were not routinely performed. Second, the survival benefit of OP could have been confounded by the treatment period of ceritinib. The OP-negative group includes patients who were given ceritinib for a short period of time due to lack of response. However, we tried to minimize this bias by a subgroup analysis of patient who were treated for at least 8 weeks, and found that the occurrence of OP is still a prognostic factor in terms of both PFS and OS. Third, we cannot fully rule out the possibility of a fatal OP. Although most of our patients had reversible and non-fatal events, complete resolution was not confirmed in two patients. Therefore, the possibility of a life-threatening condition cannot be excluded since grade 3/4 pneumonitis have been reported to occur in larger clinical trials [10].

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings suggest that OP frequently occurs in patients treated with ceritinib. OP diagnosis should be considered in patients with newly developed lung lesions that appear as nodules, consolidations, parenchymal bands, or GGOs in CT images, and must be distinguished from cancer progression. Managements with temporary drug interruption and/or corticosteroids to anticipate for radiologic improvements could be a possible option. Tissue biopsy could be confirmatory in ambiguous cases. Because OP appeared to be reversible without fatal complications in our study, permanent drug cessation may not be necessary and re-challenge could be considered in cases with grade 1 or 2 toxicities. Most importantly, OP occurrence is related to better survival outcomes. We anticipate that future prospective studies with larger populations would better characterize and improve upon these findings.

References

Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE Jr, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733–48.

Schlesinger C, Koss MN. The organizing pneumonias: a critical review of current concepts and treatment. Treat Respir Med. 2006;5(3):193–206.

Cordier JF. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(2):422–46.

Noonan SA, Sachs PB, Camidge DR. Transient asymptomatic pulmonary opacities occurring during osimertinib treatment. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(12):2253–8.

Lee H, Lee HY, Sun JM, Lee SH, Kim Y, Park SE, et al. Transient asymptomatic pulmonary opacities during osimertinib treatment and its clinical implication. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(8):1106–12.

Soria JC, Tan DSW, Chiari R, Wu YL, Paz-Ares L, Wolf J, et al. First-line ceritinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):917–29.

Shaw AT, Kim TM, Crino L, Gridelli C, Kiura K, Liu G, et al. Ceritinib versus chemotherapy in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer previously given chemotherapy and crizotinib (ASCEND-5): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(7):874–86.

Lim SM, Kim HR, Lee JS, Lee KH, Lee YG, Min YJ, et al. Open-label, multicenter, phase II study of ceritinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harboring ROS1 rearrangement. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(23):2613–8.

Cho BC, Obermannova R, Bearz A, McKeage M, Kim DW, Batra U, et al. Efficacy and safety of ceritinib (450 mg/d or 600 mg/d) with food versus 750-mg/d fasted in patients with ALK receptor tyrosine kinase (ALK)-positive NSCLC: primary efficacy results from the ASCEND-8 study. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(7):1255–65.

Kim DW, Mehra R, Tan DSW, Felip E, Chow LQM, Camidge DR, et al. Activity and safety of ceritinib in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-1): updated results from the multicentre, open-label, phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(4):452–63.

Lim SM, An HJ, Park HS, Kwon HJ, Kim EY, Hur J, et al. Organizing pneumonia resembling disease progression in a non-small-cell lung cancer patient receiving ceritinib: a case report. Medicine (Baltim). 2018;97(31):e11646.

Bender L, Meyer G, Quoix E, Mennecier B. Ceritinib-related interstitial lung disease improving after treatment cessation without recurrence under either crizotinib or brigatinib: a case report. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(5):106.

Pellegrino B, Facchinetti F, Bordi P, Silva M, Gnetti L, Tiseo M. Lung toxicity in non-small-cell lung cancer patients exposed to ALK inhibitors: report of a peculiar case and systematic review of the literature. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(2):e151–61.

Facchinetti F, Gnetti L, Balestra V, Silva M, Silini EM, Ventura L, et al. Sarcoid-like reaction mimicking disease progression in an ALK-positive lung cancer patient receiving lorlatinib. Investig New Drugs. 2019;37(2):360–3.

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47.

Zare Mehrjardi M, Kahkouee S, Pourabdollah M. Radio-pathological correlation of organizing pneumonia (OP): a pictorial review. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1071):20160723.

Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(9):829–38.

Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Felip E, Soo RA, Camidge DR, et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(12):1654–67.

Gibney GT, Weiner LM, Atkins MB. Predictive biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor-based immunotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):e542–51.

Park W, Lopes G. Perspectives: neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a potential biomarker in immune checkpoint inhibitor for non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(3):143–7.

Gettinger SN, Bazhenova LA, Langer CJ, Salgia R, Gold KA, Rosell R, et al. Activity and safety of brigatinib in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer and other malignancies: a single-arm, open-label, phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1683–96.

Hwang HJ, Kim MY, Choi CM, Lee JC. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibitor related pneumonitis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: clinical and radiologic characteristics and risk factors. Medicine (Baltim). 2019;98(48):e18131.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (no. 2018R1D1A1B07040599).

Conflict of Interest

Wonyoung Choi, Hyun-ju Lim, Seog-Yun Park, Ji-Youn Han, Heung Tae Kim, Jin Soo Lee, and Youngjoo Lee declare that they have no conflicts of interest that might be relevant to the contents of this article.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Cancer Center (IRB number; NCC2019-0239).

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choi, W., Lim, Hj., Park, SY. et al. Ceritinib-Induced Organizing Pneumonia in Lung Cancer: A Retrospective Analysis. Targ Oncol 15, 513–522 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-020-00733-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-020-00733-x