Abstract

The Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey has been widely used and has proven to be a valid and reliable scale for assessing health-related quality of life (HRQoL). However, research on HRQoL and validation of measurement scales in Mexico for its use with older persons is still incipient. The objective of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of SF-36 in a sample of 1,915 community-dwelling Mexicans 60 years and older, from two Mexican cities. Item mean scores were lowest in the dimensions of General Health (58.6), Social Functioning (58.9) Role Physical (66.5) and Vitality (67.8), and the highest mean scores were obtained in the Role Emotional (82.2), Mental Health (76.9), Bodily Pain (72.2) and Physical Functioning (70.3). The SF-36 showed appropriate internal consistency, construct validity, and factor structure. Reliability results showed a Cronbach’s alpha with coefficient for all subscales between 0.79 and 0.87 indicating good reliability. Exploratory factor analysis showed six factors, different from its original structure. The Social functioning subscale presented the least acceptable results, which may reflect different understandings in the Mexican older population. The SF-36 showed good discrimination between groups of individuals with and without chronic diseases, and high correlation between depressive symptoms, economic situation, and social support. Results show that the SF-36 is adequate for use in Mexican older persons. In future studies, health outcomes for this population group in Mexico may be consistently assessed using the SF-36.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Measuring the health status of the population is of great relevance for the planning, design, implementation, and evaluation of interventions, as well as in the estimation of their impact on different health outcomes such as disability, frailty and mortality (OECD, 2018). To seek comprehensive indicators of health status beyond the presence or absence of diseases and / or mortality, various conceptual models of health related quality of life (Bakas et al., 2012; Fernández-Mayoralas & Rojo, 2005; Urzúa, 2010) and instruments to asses it have been developed. These incorporate the point of view or perception of health at the individual level, and their feelings towards their life experiences and the impact of these on their health and well-being (Cooke et al., 2016; McDowell, 2006; Ware, 1995). In this sense, within the medical literature and measures of health status, the constructs of quality of life (QoL) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were created as multidimensional measures of self-perceived health status (Karimi & Brazier, 2016; McDowell, 2006; Oksuz & Malhan, 2006).

At the individual level, HRQoL has to do with those aspects related to the perception of health experienced and declared by the person, particularly in the physical, mental, and social dimensions, and their general perception of health and its associated factors including social support, socioeconomic status, and health condition, among others. On the other hand, at the context level, it includes resources, policies and strategies that impact people's perceptions of health and their functional capacity (Bowling, 2001; Bowling et al., 2002).

To measure HRQoL, numerous scales and questionnaires have been developed with different dimensions and scopes (McDowell, 2006; Velarde-Jurado and Avila-Figueroa, 2002; Yanguas Lezaun, 2006). The SF-36 Health Survey, developed as a multidimensional measure to assess health statuses and outcomes from the patient's point of view, is an example. Designed for use in clinical practice, research, health policy evaluation, and in general and population-specific surveys (McDowell, 2006; Ware & Gandek, 1994; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992), it is one of the most widely used measures since 1985 (Hickey et al., 2005). Its predictive validity was first documented by the International Quality of Life Assessment Project (IQOLA), which translated, validated and adapted the SF-36 Health Survey in seven European countries, followed by its application in more than forty countries (Gandek & Ware, 1998; Ware & Gandek, 1998a, 1998b). In these studies, the SF-36 Health Survey showed high internal consistency and reliability and being suitable for use with different age groups and populations (Aaronson et al., 1992; Anderson et al., 1993; Bullinger et al., 1998; Leplège et al., 1998; Sullivan et al., 1995; Vilagut et al., 2005; Ware et al., 1998).

After those initial works, a large number of studies have been conducted to determine the feasibility of translating the SF-36 into other languages and populations. Reliability and validity have been established for the population of China (Lam et al., 1998; Li et al., 2003) Hong Kong (Lam et al., 2005); New Zealand (Scott et al., 1999), in Mexican Americans (Peek et al., 2004) and Chinese Americans in the United States (Ren et al., 1998), in Peru (Salazar & Bernabé, 2015), Jordan (Khader et al., 2011), Nigeria (Mbada et al., 2015), ethnic minorities in the Netherlands (Hoopman et al., 2006), among others (Maciel et al., 2018; Hajian-Tilaki et al., 2017).

In more recent years, HRQoL has been recognised as an important outcome measure used in the field of geriatrics and gerontology (Hickey et al., 2005). Studies have evaluated the reliability and validity of the use of the SF-36 Health Survey in older persons, and reported adequate psychometric properties in studies with older persons in China (Azen et al., 1999; Ran et al., 2017), Korea (Kim et al., 2013), Vietnam (Ngo-Metzger et al., 2008), Spain (Alonso et al., 1995; López-García, et al., 2003), the United States (Barile et al., 2016; Gandek et al., 2004), as well as in Latin American countries, such as Costa Rica (Solano-Mora et al., 2015; Valdivieso-Mora et al., 2018), Brazil (Laguardia et al., 2011; Lima et al., 2009), Chile (Lera et al., 2013), and Colombia (Massa, 2010).

In Mexico, few studies have evaluated the psychometric properties and normative data of the SF-36 for Mexican population groups, finding optimal validity and reliability (Zúniga et al., 1999; Durán-Arenas et al., 2004). Additionally, the SF-36 has been used as an association measure between health-related quality of life and sarcopenia (Manrique-Espinoza, et al., 2017), the use of preventive health services and the practice of physical activity (Gallegos-Carrillo et al., 2019), social networks (Gallegos-Carrillo et al., 2009), and the effectiveness of health care interventions and programs in older persons (Gallegos-Carrillo et al., 2008). However, the use of the SF-36 in the Mexican older persons has been limited. Only one study on the factor structure of the SF-36 Health Survey in Mexican older persons was identified (Aguirre et al., 2022) and, to our knowledge, previous studies did not provide extensive investigation of the overall psychometric properties of the SF-36 applied specifically for adults 60 years and older.

The present study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Short Form-36 Version 2 Health Survey, in a representative sample of older persons in Mexico living in the community.

Methods

Data collection

Data for the study was collected as part of a larger project, the Health and Living Conditions of Older Persons, conducted in Mexico City and Xalapa, Veracruz. Both cities are important metropolitan areas, in two of the federal entities in the country with the largest proportion of adults 60 years and older. In 2020, 16.2% and 14.4% of total population in Mexico City and Veracruz respectively, were aged 60 years and over (INEGI, 2021). The study included a probabilistic sampling design representative of the community dwelling population aged 60 years and older in both cities. The sampling frame used is the National Statistics Institute, INEGI, National Housing Framework 2016, developed from the cartographic and demographic information obtained in the 2010 Population and Housing Census (INEGI, 2016). A multi-stage clustered sample was used. The first stage consisted of a systematic random sample selection of census tracts (Areas Geográficas Estadísticas Básicas or AGEBs in Spanish) (primary sample units). The second stage consisted in selecting a systematic random sample of census blocks with proportional probability to the size of the AGEBs (secondary sample units). In the third and fourth stages a simple random selection of (a) households (tertiary sample units) and (b) persons aged 60 years or above who lived in those houses (quaternary sample units of the survey) was performed. The expected sample size (2,341 households), considering a 15% of non-response rate, guaranteed an 85% statistical power. The sampling design ensured a representative sample across both cities and representing all socioeconomic strata. Data collection was carried out from September 2018 to January 2019 using face-to-face paper interviews conducted by trained interviewers in the respondents’ home. Inclusion criteria to participate in the project included being 60 years and over, not having cognitive impairment and being regular residents of the selected household. The Spanish version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Villaseñor-Cabrera et al, 2010) was completed to find whether the participants showed signs of cognitive impairment. Those with a score < 24 were excluded from the study. A total of 2,024 direct in-person interviews were conducted (response rate = 85.4%). For the current analyses, the responses of 109 participants were excluded. Thus, the final analytical sample comprised 1,915 participants.

A comprehensive questionnaire was purposely developed to investigate the demographic, socioeconomic and health characteristics of the study population, their social support networks, and intra-family relationships. To evaluate Health Related Quality of Life, the questionnaire included the Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36) (Ware & Sherbourne, 1992). The SF-36 is a 36-item scale grouped in eight subscales, each representing a health-related domain: physical functioning (ten items); physical role limitations (four items); bodily pain (two items); general health perceptions (five items); energy/vitality (four items); social functioning (two items); emotional role limitations (three items) and mental health (five items) and a single item that provides an indication of perceived change in health and is excluded from the scoring (Ware et al., 1993). The SF-36 score was calculated using the standard approach consisting of the sum of the items on each subscale. Item responses were transformed so that each subscale presents values between 0 and 100, where 0 represents the worst possible state of health and 100 represents the best possible state of health. Missing values were not imputed as recommended in the SF-36 User Manual, to report actual scores (Ware et al, 1993; Ware and Gandek, 1994; Ware et al., 1998). After each item response was transformed, the eight SF-36 subscales were generated (Ware et al., 1994).

Analysis

Following the IQOLA Project process and standards for validation and psychometric testing of the SF-36 Health Survey (Ware & Gandek, 1998b; Ware et al, 1993; Ware and Gandek, 1994; Ware et al., 1998), and several studies using these methods (Leplège et al., 1998; Sanson-Fisher & Perkins, 1998), the following analyses were conducted.

We examined data distribution, completeness, as well as out-of-range data and descriptive statistics were generated to obtain the percentage of missing data for each SF-36 item and the eight subscales. To evaluate response distributions, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, coefficient of variation, skewness, and kurtosis. The distribution of responses for each question was assessed visually and the percentage of responses on extreme values was examined for each subscale to detect floor or ceiling effects which were considered present if at least 15% of respondents achieved the lowest or highest possible score, respectively (Terwee et al., 2007). Item-level analyses were conducted next to examine if items could be aggregated into multi-item scales and if the scale structure in our sample conforms to the assumptions underlying the original SF-36 studies. For each of the SF-36 subscales, the following item-level analysis were included: (1) item internal consistency through item-scale correlations. Data were considered substantial and satisfactory when correlation between an item and its hypothesized scale was at least 0.40, the accepted standard (Perneger, et al., 1995); (2) item discriminant validity of each subscale by evaluating the average of item-total score with the average of the correlations of its items with the remaining subscales. Discriminant validity is considered successful when the correlation between an item and its own subscale is significantly higher, by two standard errors or more, than its correlation with other scales; (3) internal consistency reliability of the scale and the eight subscales was evaluated using Cronbach's Alpha coefficient (Cronbach, 1951; Henson, 2001).

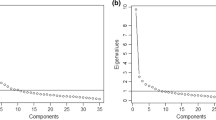

In addition, we used factor analysis to explore the underlying structure of the SF-36 in our sample compared to the structure derived from the original US study and subsequent validation studies in other countries and population groups. The original US study and most studies validating the SF-36 though factor analysis have produced first order eight factor structures and two-factor structures of physical and mental health (Gandek & Ware, 1998; Reed, 1998; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992; Ware et al., 1998), while analyses in some non-Western and low- and middle-income countries have turned different factor structures (Kim et al., 2013; Suzukamo et al, 2011; AboAbat et al., 2020; Salazar & Bernabé, 2015). To evaluate the factor structure of the SF-36 in our study sample we conducted the following analysis. To evaluate if the data were appropriate, we estimated the correlation matrix among the eight subscales, the Bartlett sphericity test and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) sample adequacy test (Campo-Arias et al., 2012). High correlation between the subscales, a KMO measure of sampling adequacy ≥ 0.7 and a score close to 0.05 in Bartlett’s sphericity test were defined to establish the adequacy for this data. After verifying the data were appropriate, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis. Factors were extracted using the principal components method, establishing Eigenvalues ≥ 1 as criteria for retaining factors, in addition to the examination of the sedimentation graph (scree plot) of the factor analysis (Guttman, 1954).

Convergent validity of the SF-36 was tested by estimating the strength of the correlation between measures of economic situation, mental health, and perceived social support from spouse/partner, children, and friends. Depressive symptoms were measured by the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986; Yesavage et al., 1982), which has been previously validated in the Mexican population showing reliability and validity (Acosta Quiroz et al., 2021). The GDS-15 scale includes dichotomous responses (Yes/No); a score equal to or greater than five positive items indicate depressive symptoms. Economic situation is self-reported by participants and categorised as Very Good/Good; Fair, and Poor/Very poor. To measure social support, we use a set of questions included in the Mexican Health and Aging Study, MHAS, a longitudinal and nationally representative study of adults 50 years and older living in the community. Social support is attained in the MHAS as self-reported perceived support by respondent from spouse-partner/children/friends in four different areas, if they understand their feelings, if they feel he/she can confide in them, if they listen to them (a lot, little, nothing), and if they disappoint them (reverse score) (MHAS 2012). Our hypothesis postulates to find a modest to moderate correlation between the total score of each SF-36 subscales and the other measures.

Criterion-based discriminant validity was also assessed using known-groups validity. This allowed to explore the ability of the questionnaire to discriminate among subgroups of respondents known to differ in criteria assessed independently such as key clinical variables. Our hypothesis is that those individuals in the group of good health conditions, will have a higher score in each of the eight subscales of the SF-36 (better health-related quality of life), in contrast to those who are in the group of poor health conditions. Respondents were assigned to mutually exclusive groups differing in each of these characteristics. Participants with good health conditions included those who reported having none of the following health conditions: diabetes, hypertension, chronic respiratory illness, heart attack, stroke, disabling pain, urgency and stress related urinary incontinence, and painful arthritis. Those in the bad health group presented at least one of these same health conditions. The t-test were performed to test the statistical significance of the observed differences between the subgroups. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata v.14.0 (StataCorp, 2015).

Ethical considerations

The protocol was evaluated and approved by the Ethics in Research Committee and the Research Committee of the National Institute of Geriatrics (registration DI-PI-007/2018). Each participant who was invited to participate received a fact sheet about the project and had the opportunity to ask questions about it. Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants who agreed to participate. The project was funded by the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACyT, for its acronym in Spanish) under the Call for Basic Scientific Research (CB-2016/287302).

Results

Our working sample consisted of 1,915 Mexican older persons of which 64% were women, with a mean age of 72 years (SD 8) and general low educational attainment with 52% of the sample completing primary level education or had no schooling.

Item Descriptive Statistics

Completion rate was high (> 97%), the domain with the higher missing data was physical function with 2.9% (results not shown). Table 1 presents the description of each of the SF-36 domains. Item mean scores were lowest in the dimensions of General Health (58.6), Social Functioning (58.9) Role Physical (66.5) and Vitality (67.8), and the highest mean scores were obtained in the Role Emotional (82.2), Mental Health (76.9), Bodily Pain (72.2) and Physical Functioning (70.3).

Skewness calculations showed all subscales were negatively skewed with the Role-Emotional, Mental Health, Physical Functioning, Bodily Pain and Role-Physical subscales presenting a moderately skewed distribution. The highest floor effects were observed for the Role-Physical and Role-Emotional subscales, at 25.9% and 12.4%, respectively. Regarding ceiling effects, these were found also in these two subscales (58.9% and 76.5%, respectively), while moderate effects were present for the Bodily Pain (41.5%) and Physical Functioning (26.1%) subscales (Table 1).

Scaling Assumptions, Validity, and Reliability

Table 2 presents the psychometric properties of the SF-36 subscales. All items passed the test for discriminant validity, with correlation coefficients between items and the hypothesised scale, higher or equal than 0.40, except for the Social Functioning and Role Emotional subscales. The highest correlation coefficient was between the Mental Health and the Vitality subscales, which measure the emotional dimension of health, while Social Functioning presented the lowest correlation coefficients. On the other hand, the correlations between three of the dimensions of physical health: Physical Functioning, Role Physical, and Bodily Pain were also high (> 0.50). Cronbach alpha coefficients ranged from 0.79 to 0.87, indicating good reliability (Table 2).

Tests of adequacy of the data for performing factor analysis showed the determinant of the correlation matrix was equal to 0.000, a Bartlett test of sphericity Chi-square = 40,678.335 (p-value = 0.000) and a value of 0.951 in the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling, confirming the variables are not intercorrelated, the data is adequate, and one can proceed with factor analysis estimations. The exploratory factor analysis on all the items of the SF-36 resulted in the extraction of six factors: Physical Function, Vitality and Mental Health, Role Physical, Role Emotional, General Health, and Bodily Pain, with eigenvalues equal to or greater than one. Factors 1 and 2 account for almost half of all the variance (47%), with eigenvalues of 13.4 and 2.9, respectively (Table 3).

Physical and health items loaded within their hypothesized scales (General Health, Physical Function, Role Physical and Bodily Pain), but some items in the Role Physical and Bodily Pain present cross-loadings. Mental Health and Vitality items loaded on the same factor instead of loading on a separate factor each and several items show cross-loadings. The Social Function items showed problematic results with the first item (Q. 20) presenting low factor loadings (< 0.40) and cross-loading among three factors, and the second item showing even lower factor loadings (< 0.30) and large uniqueness (86%), showing it does not fall into any of the factors (Table 3).

Convergent Validity

Table 4 presents the correlation coefficients between the eight SF-36 subscales and the variables mental health, economic situation, and social support. Correlations were all negative between depressive symptoms and economic situation and all SF-36 subscales. The hypothesis that respondents presenting higher depressive symptoms and worse economic situation would present lower health-related quality of life was confirmed. All coefficients were statistically significant (p < 0.001) apart from economic situation and Social Functioning.

For the three social support groups, spouse/partner, children, and friends, correlations were negative for the questions on how much participants perceived they understood their feelings, that they can confide in them, and that they listen when they need to talk about their worries. This shows that the less social support participants perceive (higher score), the lower their perceived health related quality of life is (lower score). These coefficients are moderate to low and statistically significant (p < 0.05 or lower) for all subscales, except for the Social Function subscale that was only significant for how much participants perceive friends, but not their spouse or children, understand their feelings and listen when they need to talk about their worries. For all three social support groups, as participants reported less disappointment (reverse score), the higher they reported their perceived health related quality of life. As with the rest of the social support questions, the correlation coefficients are moderate to low and statistically significant apart from the Social Functioning subscale (Table 4).

Discriminant validity (known-groups approach)

The results of the known-groups validity analysis are presented in Table 5. The second hypothesis that respondents in good health would report better scores in all SF-36 subscales was confirmed. Those in the bad health subgroup (n = 1,303) show consistently lower means in most subscales that those in the good health subgroup (n = 610), and these differences are statistically significant. The only subscale with a minor difference was Social Functioning, and this difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

This article describes the results of the study of the psychometric properties of the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) in a sample of Mexican older persons. The Spanish SF-36 scale previously translated and tested in other Spanish-speaking populations (Durán-Arenas et al., 2004; Vilagut et al., 2005) was administered as part of a comprehensive questionnaire. This paper shows that psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey in older persons were satisfactory according to the criteria set by original studies, showing the validity and convenience of its use in community dwelling older people in Mexico.

Previous studies of normative data of the SF-36 Health Survey in Mexico have been conducted in samples of adults (Durán-Arenas et al., 2004; Zúniga et al., 1999), and few studies have explored the association of HRQoL with use of health services, depressive symptoms, chronic diseases and sarcopenia (Gallegos-Carrillo et al., 2009; 2008; Manrique-Espinoza et al., 2017) in adults 60 years and older. To our knowledge, there is only one study that explores the factor structure of the SF-36 Health Survey in older adults (Aguirre et al., 2022), but no previous studies conducted a comprehensive validation of the SF-36 survey in this population group. Therefore, this is the first comprehensive study validating the SF-36 Health Survey, using a representative sample of Mexican older persons. The acceptability of the questionnaire was considered high given the missing responses were less than 3%. Floor and ceiling effects were comparable to those found in other studies, with highest scores observed for the Role Physical and Role Emotional subscales (Garratt & Stavem, 2017; Salazar & Bernabé, 2015; Sanson-Fisher & Perkins, 1998). High positive mean scores have been found in previous studies with older persons, mainly on the Role Emotional subscale (Meng et al., 2013; Hoopman et al., 2006).

The internal consistency coefficients are satisfactory and within expected range for all the subscales according to results from the original validation studies and previous studies in other countries (item-test ≥ 0.70, item-total ≥ 0.50, and inter-item correlation 0.35–0.48). Highest correlations were observed between the subscales measuring physical health aspects. The Role Emotional subscale showed slightly lower correlation with subscales measuring physical health aspects, but higher correlations with most of the subscales measuring mental aspects. In addition, our findings also show the highest correlation between the Mental Health and Vitality subscales (0.70), given their strong association with mental health rather than with physical health (Fuh et al., 2000; Lam et al., 1998; Leplège et al., 1998; Lewin-Epstein et al., 1998; Lim et al., 2008; McHorney et al., 1994; Montazeri et al., 2005; Ngo-Metzger et al., 2008; Ren et al., 1998).

The Social Functioning subscale had significantly lower correlations with all subscales showing low reliability. Interestingly, the low or unsatisfactory results of the internal consistency reliability of the Social Functioning subscale was previously noted in several studies in Asia (Azen et al., 1999; Fuh et al., 2000; Li et al., 2003; Lim et al., 2008; Ngo-Metzger et al., 2008; Tseng et al., 2003), and Brazil (Laguardia et al., 2011).

This studies note that different cultures give different meaning to physical and mental health constructs, and that there are cultural differences in the concept of social functioning as well as in perceptions about concepts such as pain and vitality (Fuh et al., 2000; Lim et al., 2008; Ngo-Metzger et al., 2008; Tseng et al., 2003). For example, it has been noted that traditional health beliefs of many Asian populations do not involve a strict dichotomization of physical versus mental health, but instead, health is viewed as a balance of yin and yang (hot and cold) principles. Also, it has been noted how Asian populations may conceptualize mental and physical health differently than Western populations (Fuh et al., 2000; Ngo-Metzger et al., 2008; Tseng et al., 2003).

With respect to convergent validity, all subscales of the SF-36 were negatively correlated with depressive symptoms, and these were statistically significant (p < 0.01). This negative and statistically significant association was also found in previous studies (Azen et al., 1999). The SF-36 also shows good discrimination between groups of people with and without chronic diseases as found in previous studies (Hoopman et al., 2006; Laguardia et al., 2011; Tyack et al., 2018), also suggesting good construct validity. There was a statistically significant difference between the scores of all scales between the two groups, except for the Social Functioning scale where the scores were almost equal, and the difference was not statistically significant.

Exploratory factor analysis of individual items resulted in a partial correspondence of the items to their hypothesized scales, with exception of the Vitality, Mental Health, and Social Functioning subscales, resulting in a six-factor solution. Variations in the factor structure of the SF-36 survey have been noted previously. The results of a recent study validating the factor structure of the SF-36 in a sample of older persons in two states in Northern Mexico support a four-factor structure (Physical Function, Body Pain, Role Physical and Psychological Health), with a reduced number of items in each of these subscales (Aguirre et al., 2022). A study in general population in Korea produced a six-factor solution (Kim et al., 2013) where, as with our study, the Social Function items loaded with the factors that include the Mental Health and Vitality items. In our study, the Social Function items also loaded with the factors that include the Role Emotional and Role Physical items. These similar results show an important point about how different populations perceive and value their physical and mental health and how these impact their overall wellbeing and engagement. The way cultural systems influence and shape physical and mental health, health behaviours, perceptions, how people cope and seek help has been well documented (Angel & Thoits, 1987; Hwang et al, 2008; Lora, 2012).

Of particular interest is the Social Function subscale, where some authors have noted difficulties as a result of the existence of only two items in this subscale (Walters et al., 2001), the high difficulty in translating its two questions (Wagner et al., 1998), or due to problems with the conceptualization of social function, the local understanding of the meaning of social activities, as well as how well individuals understand the differences between the extent of time included in the questions (i.e. all of the time, most of the time) (Kim et al., 2013; Ngo-Metzger et al., 2008; Tseng et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2008, 2015).

Following the results obtained with the Social Function scale of our study, an adaptation of the two items included in the survey which better represent local cultural norms, is suggested as follows. First, in Mexico, the notion of social activities can be frequently interpreted as relationships with or help with daily activities to people from other households. Therefore, the connotation of social activities should be replaced by a term that conveys the meaning of contact between the people interviewed with others close to them. Specifically, including specific references to participation in family gatherings, visiting friends, neighbours or relatives. The second recommendation is to change the structure of the questions in Spanish so that they first ask about the difficulty that the person has had to make contact, visit or participate in gatherings with family or other acquaintances, as a result of their health or emotional problems. The recommended wording in Spanish for these two items is as follows:

-

ORIGINAL: Durante las 4 últimas semanas, ¿hasta qué punto su salud física o los problemas emocionales han dificultado sus actividades sociales habituales con la familia, los amigos, los vecinos u otras personas?

-

MODIFIED: Durante las 4 últimas semanas ¿ha tenido dificultad para participar en reuniones familiares o visitar amigos, vecinos o familiares, por problemas de salud física o emocional?

-

MODIFIED: In the past four weeks, have you had difficulties participating in family reunions or visiting friends, neighbours or family due to physical or emotional health problems?

-

ORIGINAL: Durante las 4 últimas semanas, ¿con qué frecuencia la salud física o los problemas emocionales le han dificultado sus actividades sociales (como visitar a los amigos o familiares)?

-

MODIFIED: Durante las 4 últimas semanas, ¿con qué frecuencia se le ha dificultado participar en reuniones familiares o visitar amigos, vecinos o familiares, por problemas de salud física o emocional?

-

MODIFIED: In the past four weeks, how often have you had difficulty participating in family reunions or visiting friends, neighbours or family due to physical or emotional health problems?

Given the importance of assessing older persons’ wellbeing beyond their chronic conditions, there is still a growing need for the development or adaptation of optimal outcome measures that are culturally appropriate. Moreover, by using adequate tools, researchers and health practitioners can promote better quality of life among older persons.

This study advances knowledge in the topic by presenting the psychometric properties of the SF-36 Health Survey and its validity. As such, this study has important strengths, first, compared to previous studies in Mexico that have focused on general population (Zúniga et al., 1999; Durán-Arenas et al., 2004) or few aspects of the scale validation (Aguirre et al., 2022), to our knowledge, this is the first to include a comprehensive evaluation of the psychometric properties of the SF-36 Health Survey using a representative sample of older persons, allowing for a better understanding of the scores and the application of the SF-36 Health Survey in Mexico. Considering the study’s findings, it also presents the relevance of cultural factors in generating, adapting, validating, and applying health questionnaires. It also has methodological strengths based on the large random representative sample of older persons, and conducted under strict standardisation of all fieldwork staff, in addition to very high response rates and data completeness.

Notwithstanding, we identify two limitations in the study that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, while the study uses a representative sample of older persons in Mexico, the localities are mostly urban and therefore, results cannot be generalised to rural areas. Second, this study did not include test–retest reliability data, as at this time the full questionnaire was only administered once. However, a second wave of the larger project is currently underway and so we expect to add this to the validation tests.

In the future, research should extend to other regions of the country, including rural areas, to elicit similarities and possible differences in validating scales as the SF-36. To fully understand how Mexican culture and values influence the scores of this and other quality of life measurements, future studies should consider including qualitative methods that explore these factors in-depth. In turn, this would also allow for a better understanding of the few divergent results from the original IQOLA project studies and previous studies validating the SF-36 Health Survey, particularly in the role of mental health and social functioning in the country. These differences do not invalidate the validity and reliability of the SF-36 to measure health-related quality of life in Mexican older persons but point to the need of investigating which tools are most appropriate for local use.

References

Aaronson, N. K., Acquadro, C., Alonso, J., Apolone, G., Bucquet, D., Bullinger, M., Bungay, K., Fukuhara, S., Gandek, B., & Keller, S. (1992). International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 1(5), 349–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00434949

AboAbat, A., Qannam, H., Bjorner, J. B., & Al-Tannir, M. (2020). Psychometric validation of a Saudi Arabian version of the sf-36v2 health survey and norm data for Saudi Arabia. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes, 4(1), 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-020-00233-6

Acosta Quiroz, C. O., García-Flores, R., & Echeverría-Castro, S. B. (2021). The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15): Validation in Mexico and Disorder in the State of Knowledge. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 93(3), 854–863. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415020957387

Aguirre, S. I., Ornelas, M., Blanco, H., Jurado-García, P. J., Benavides, E. V., Rodríguez-Villalobos, J. M., Jiménez-Lira, C., & Blanco, J. R. (2022). Quality of Life in Mexican Older Adults: Factor Structure of the SF-36 Questionnaire. Healthcare (basel, Switzerland), 10(2), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10020200

Alonso, J., Prieto, L., & Antó, J. M. (1995). La versión española del SF-36 Health Survey (Cuestionario de Salud SF-36): Un instrumento para la medida de los resultados clínicos [The Spanish version of the SF-36 Health Survey (the SF-36 health questionnaire): An instrument for measuring clinical results]. Medicina Clinica, 104(20), 771–776.

Anderson, R. T., Aaronson, N. K., & Wilkin, D. (1993). Critical review of the international assessments of health-related quality of life. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 2(6), 369–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00082-1

Angel, R., & Thoits, P. (1987). The impact of culture on the cognitive structure of illness. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 11(4), 465–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00048494

Azen, S. P., Palmer, J. M., Carlson, M., Mandel, D., Cherry, B. J., Fanchiang, S. P., Jackson, J., & Clark, F. (1999). Psychometric properties of a Chinese translation of the SF-36 health survey questionnaire in the Well Elderly Study. Journal of Aging and Health, 11(2), 240–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/089826439901100206

Bakas, T., McLennon, S. M., Carpenter, J. S., Buelow, J. M., Otte, J. L., Hanna, K. M., Ellett, M. L., Hadler, K. A., & Welch, J. L. (2012). Systematic review of health-related quality of life models. Health and quality of life outcomes, 10, 134. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-134

Barile, J. P., Horner-Johnson, W., Krahn, G., Zack, M., Miranda, D., DeMichele, K., Ford, D., & Thompson, W. W. (2016). Measurement characteristics for two health-related quality of life measures in older adults: The SF-36 and the CDC Healthy Days items. Disability and Health Journal, 9(4), 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2016.04.008

Bowling, A. (2001). Health-related quality of life: Conceptual meaning, use and measurement. Measuring disease: A review of disease-specific quality of life measurement scales (2nd ed.). Open University Press.

Bowling, A., Banister, D., Sutton, S., Evans, O., & Windsor, J. (2002). A multidimensional model of the quality of life in older age. Aging & mental health, 6(4), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786021000006983

Bullinger, M., Alonso, J., Apolone, G., Leplège, A., Sullivan, M., Wood-Dauphinee, S., Gandek, B., Wagner, A., Aaronson, N., Bech, P., Fukuhara, S., Kaasa, S., & Ware, J. E., Jr (1998). Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: the IQOLA Project approach. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 51(11), 913–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00082-1

Campo-Arias, A., Herazo, E., & Oviedo, H. C. (2012). Análisis de factores: Fundamentos para la evaluación de instrumentos de medición en salud mental [Factor Analysis: Principles to Evaluate Measurement Tools for Mental Health]. Revista Colombiana De Psiquiatría, 41(3), 659–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-7450(14)60036-6

Cooke, P. J., Melchert, T. P., & Connor, K. (2016). Measuring Well-Being: A Review of Instruments. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(5), 730–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016633507

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334.

Durán-Arenas, L., Gallegos-Carrillo, K., Salinas-Escudero, G., & Martínez-Salgado, H. (2004). Hacia una base normativa mexicana en la medición de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud, mediante el Formato Corto 36 [Towards a Mexican normative standard for measurement of the short format 36 health-related quality of life instrument]. Salud Publica De Mexico, 46(4), 306–315. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0036-36342004000400005

Fernández-Mayoralas, G., & Rojo, F. (2005). Calidad de vida y salud: Planteamientos conceptuales y métodos de investigación. Territoris, 5, 117–135.

Fuh, J. L., Wang, S. J., Lu, S. R., Juang, K. D., & Lee, S. J. (2000). Psychometric evaluation of a Chinese (Taiwanese) version of the SF-36 health survey amongst middle-aged women from a rural community. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 9(6), 675–683. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1008993821633

Gallegos-Carrillo, K., García-Peña, C., Durán-Muñoz, C., Mudgal, J., Durán-Arenas, L., & Salmerón-Castro, J. (2008). Health care utilization and health-related quality of life perception in older adults: A study of the Mexican Social Security Institute. Salud Publica De Mexico, 50(3), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0036-36342008000300004

Gallegos-Carrillo, K., Mudgal, J., Sánchez-García, S., Wagner, F. A., Gallo, J. J., Salmerón, J., & García-Peña, C. (2009). Social networks and health-related quality of life: a population based study among older adults. Salud Pública de México, 51(1), 6–13. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0036-36342009000100004

Gallegos-Carrillo, K., Honorato-Cabañas, Y., Macías, N., García-Peña, C., Flores, Y. N., & Salmerón, J. (2019). Preventive health services and physical activity improve health-related quality of life in Mexican older adults. Los servicios de salud preventivos y la actividad física mejoran la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en adultos mayores mexicanos. Salud publica de Mexico, 61(2), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.21149/9400

Gandek, B., & Ware, J. E., Jr. (1998). Methods for validating and norming translations of health status questionnaires: the IQOLA Project approach. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 953–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00086-9

Gandek, B., Sinclair, S. J., Kosinski, M., & Ware, J. E., Jr. (2004). Psychometric evaluation of the SF-36 health survey in Medicare managed care. Health Care Financing Review, 25(4), 5–25.

Garratt, A. M., & Stavem, K. (2017). Measurement properties and normative data for the Norwegian SF-36: Results from a general population survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0625-9

Guttman, L. (1954). Some necessary conditions for common-factor analysis. Psychometrika, 19(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289162

Hajian-Tilaki, K., Heidari, B., & Hajian-Tilaki, A. (2017). Health Related Quality of Life and Its Socio-Demographic Determinants among Iranian Elderly People: a Population Based Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of caring sciences, 6(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.15171/jcs.2017.005

Henson, R. K. (2001). Understanding internal consistency reliability estimates: A conceptual primer on coefficient alpha. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34(3), 177–189.

Hickey, A., Barker, M., McGee, H., & O’Boyle, C. (2005). Measuring health-related quality of life in older patient populations: A review of current approaches. PharmacoEconomics, 23(10), 971–993. https://doi.org/10.2165/00019053-200523100-00002

Hoopman, R., Terwee, C. B., Muller, M. J., & Aaronson, N. K. (2006). Translation and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use among Turkish and Moroccan ethnic minority cancer patients in The Netherlands. European Journal of Cancer, 42(17), 2982–2990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.011

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, J., Gruber, K. J., & Hsueh, K. H. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the SF-36 in older adults with diabetes in Beijing. China. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 88(3), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2010.03.005

Hwang, W. C., Myers, H. F., Abe-Kim, J., & Ting, J. Y. (2008). A conceptual paradigm for understanding culture’s impact on mental health: The cultural influences on mental health (CIMH) model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.001

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2016). Inventario Nacional de Viviendas. https://www.inegi.org.mx/rnm/index.php/catalog/80/related_materials?idPro. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2021). Presentación de Resultados del Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/#Documentacion. Accessed 4 Feb 2022.

Karimi, M., & Brazier, J. (2016). Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics, 34(7), 645–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-016-0389-9

Khader, S., Hourani, M. M., & Al-Akour, N. (2011). Normative data and psychometric properties of short form 36 health survey (SF-36, version 1.0) in the population of north Jordan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 17(5), 368–374.

Kim, S. H., Jo, M. W., & Lee, S. I. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Korean short form-36 health survey version 2 for assessing the general population. Asian Nursing Research, 7(2), 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2013.03.001

Laguardia, J., Campos, M. R., Travassos, C. M., Najar, A. L., Anjos, L. A., & Vasconcellos, M. M. (2011). Psychometric evaluation of the SF-36 (v.2) questionnaire in a probability sample of Brazilian households: results of the survey Pesquisa Dimensões Sociais das Desigualdades (PDSD), Brazil, 2008. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9, 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-61

Lam, C. L., Gandek, B., Ren, X. S., & Chan, M. S. (1998). Tests of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF-36 Health Survey. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1139–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00105-x

Lam, C. L., Tse, E. Y., Gandek, B., & Fong, D. Y. (2005). The SF-36 summary scales were valid, reliable, and equivalent in a Chinese population. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 58(8), 815–822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.12.008

Leplège, A., Ecosse, E., Verdier, A., & Perneger, T. V. (1998). The French SF-36 Health Survey: Translation, cultural adaptation and preliminary psychometric evaluation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1013–1023. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00093-6

Lera, L., Fuentes-García, A., Sánchez, H., & Albala, C. (2013). Validity and reliability of the SF-36 in Chilean older adults: The ALEXANDROS study. European Journal of Ageing, 10(2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-012-0256-2

Lewin-Epstein, N., Sagiv-Schifter, T., Shabtai, E. L., & Shmueli, A. (1998). Validation of the 36-item short-form Health Survey (Hebrew version) in the adult population of Israel. Medical Care, 36(9), 1361–1370. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199809000-00008

Li, L., Wang, H. M., & Shen, Y. (2003). Chinese SF-36 Health Survey: translation, cultural adaptation, validation, and normalisation. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57(4), 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.4.259

Lim, L. L., Seubsman, S. A., & Sleigh, A. (2008). Thai SF-36 health survey: Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and validity in healthy men and women. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 6, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-6-52

Lima, M. G., Barros, M. B., César, C. L., Goldbaum, M., Carandina, L., & Ciconelli, R. M. (2009). Health related quality of life among the elderly: A population-based study using SF-36 survey. Cadernos De Saude Publica, 25(10), 2159–2167. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2009001000007

López-García, E., Banegas, J. R., Pérez-Regadera, A. G., Gutiérrez-Fisac, J. L., Alonso, J., & Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. (2003). Valores de referencia de la versión española del Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 en población adulta de más de 60 años. Medicina Clínica, 120(15), 568–573.

Lora, E. (2012). Health perceptions in Latin America. Health Policy and Planning, 27(7), 555–569. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czr078

Maciel, N. M., De Conti, M., Simeão, S., Genebra, C., Corrente, J. E., & De Vitta, A. (2018). Sociodemographic factors, level of physical activity and health-related quality of life in adults from the north-east of São Paulo, Brazil: A cross-sectional population study. British Medical Journal Open, 8(1), e017804. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017804

Manrique-Espinoza, B., Salinas-Rodríguez, A., Rosas-Carrasco, O., Gutiérrez-Robledo, L. M., & Avila-Funes, J. A. (2017). Sarcopenia Is Associated With Physical and Mental Components of Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 18(7), 636.e1-636.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.04.005

Massa, E. R. (2010). Confiabilidad del cuestionario de salud SF-36 en pacientes postinfarto agudo del miocardio procedentes de Cartagena de Indias. Colombia. Revista Colombiana De Cardiología, 17(2), 41–46.

Mbada, C. E., Adeogun, G. A., Ogunlana, M. O., Adedoyin, R. A., Akinsulore, A., Awotidebe, T. O., Idowu, O. A., & Olaoye, O. A. (2015). Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of yoruba version of the short-form 36 health survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13, 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0337-y

McDowell, I. (2006). Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires. Oxford University Press.

McHorney, C. A., Ware, J. E., Jr., Lu, J. F., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1994). The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Medical care, 32(1), 40–66. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004

McNeish, D., & Wolf, M. G. (2021). Dynamic Fit Index Cutoffs for Confirmatory Factor Analysis Models. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000425

Meng, H., King-Kallimanis, B. L., Gum, A., & Wamsley, B. (2013). Measurement bias of the SF-36 Health Survey in older adults with chronic conditions. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 22(9), 2359–2369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-013-0373-1

MHAS, Mexican Health and Aging Study. (2012). Core Questionnaire. Data Files and Documentation (public use). Available at: www.mhasweb.org. Accessed 7 May 2013.

Montazeri, A., Goshtasebi, A., Vahdaninia, M., & Gandek, B. (2005). The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 14(3), 875–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5

Ngo-Metzger, Q., Sorkin, D. H., Mangione, C. M., Gandek, B., & Hays, R. D. (2008). Evaluating the SF-36 Health Survey (Version 2) in Older Vietnamese Americans. Journal of Aging and Health, 20(4), 420–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264308315855

Oksuz, E., & Malhan, S. (2006). Compendium of health related quality of life generic instruments. Basken University.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2018). Policy use of well-being metrics: Describing countries’ experiences SDD working paper No. 94. Paris: OECD. https://one.oecd.org/document/SDD/DOC(2018)7/En/pdf. Accessed 17 Mar 2022.

Peek, M. K., Ray, L., Patel, K., Stoebner-May, D., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2004). Reliability and validity of the SF-36 among older Mexican Americans. The Gerontologist, 44(3), 418–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/44.3.418

Perneger, T. V., Leplège, A., Etter, J. F., & Rougemont, A. (1995). Validation of a French-language version of the MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) in young healthy adults. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 48(8), 1051–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(94)00227-h

Ran, L., Jiang, X., Li, B., Kong, H., Du, M., Wang, X., Yu, H., & Liu, Q. (2017). Association among activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living and health-related quality of life in elderly Yi ethnic minority. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0455-y

Reed, P. J. (1998). Medical outcomes study short form 36: Testing and cross-validating a second-order factorial structure for health system employees. Health Services Research, 33, 1361–1380.

Ren, X. S., Amick, B., 3rd., Zhou, L., & Gandek, B. (1998). Translation and psychometric evaluation of a Chinese version of the SF-36 Health Survey in the United States. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1129–1138. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00104-8

Salazar, F. R., & Bernabé, E. (2015). The Spanish SF-36 in Peru factor structure, construct validity, and internal consistency. Asia-Pacific journal of public health, 27(2), NP2372–NP2380. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539511432879

Sanson-Fisher, R. W., & Perkins, J. J. (1998). Adaptation and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Australia. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 961–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00087-0

Scott, K. M., Tobias, M. I., Sarfati, D., & Haslett, S. J. (1999). SF-36 health survey reliability, validity and norms for New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 23(4), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842x.1999.tb01282.x

Sheikh, J. I., & Yesavage, J. A. (1986). Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health, 5(1–2), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09

Solano-Mora, L., Moncada-Jiménez, J., Araya-Vargas, G., & Jiménez-Torres, J. (2015). Validez factorial del Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 en jubilados universitarios costarricenses. Revista Costarricense De Salud Pública, 24(2), 143–152.

StataCorp. (2015). Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. StataCorp LP.

Sullivan, M., Karlsson, J., & Ware, J. E., Jr. (1995). The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey–I. Evaluation of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and construct validity across general populations in Sweden. Social science & medicine, 41(10), 1349–1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00125-q

Suzukamo, Y., Fukuhara, S., Green, J., Kosinski, M., Gandek, B., & Ware, J. E. (2011). Validation testing of a three-component model of Short Form-36 scores. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(3), 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.017

Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

Tseng, H. M., Lu, J. F., & Gandek, B. (2003). Cultural issues in using the SF-36 Health Survey in Asia: Results from Taiwan. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 1, 72. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-1-72

Tyack, Z., Kuys, S., Cornwell, P., Frakes, K. A., & McPhail, S. (2018). Health-related quality of life of people with multimorbidity at a community-based, interprofessional student-assisted clinic: Implications for assessment and intervention. Chronic Illness, 14(3), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742395317724849

Urzúa, M. A. (2010). Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud: Elementos conceptuales [Health related quality of life: Conceptual elements]. Revista Médica De Chile, 138(3), 358–365.

Valdivieso-Mora, E., Ivanisevic, M., Shaw, L. A., Garnier-Villarreal, M., Green, Z. D., Salazar-Villanea, M., Moncada-Jiménez, J., & Johnson, D. K. (2018). Health-related quality of life of older adults in Costa Rica as measured by the Short-Form-36 health survey. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 4. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721418782812

Velarde-Jurado, E., & Avila-Figueroa, C. (2002). Evaluación de la calidad de vida. Salud Pública De México, 44(4), 349–361.

Vilagut, G., Ferrer, M., Rajmil, L., Rebollo, P., Permanyer-Miralda, G., Quintana, J. M., Santed, R., Valderas, J. M., Ribera, A., Domingo-Salvany, A., & Alonso, J. (2005). El Cuestionario de Salud SF-36 español: una década de experiencia y nuevos desarrollos [The Spanish version of the Short Form 36 Health Survey: a decade of experience and new developments]. Gaceta sanitaria, 19(2), 135–150.

Villaseñor-Cabrera, T., Guàrdia-Olmos, J., Jiménez-Maldonado, M., Rizo-Curiel, G., & Peró-Cebollero, M. (2010). Sensitivity and specificity of the Mini-Mental State Examination in the Mexican population. Quality & Quantity, 44, 1105–1112.

Wagner, A. K., Gandek, B., Aaronson, N. K., Acquadro, C., Alonso, J., Apolone, G., Bullinger, M., Bjorner, J., Fukuhara, S., Kaasa, S., Leplège, A., Sullivan, M., Wood-Dauphinee, S., & Ware, J. E., Jr. (1998). Cross-cultural comparisons of the content of SF-36 translations across 10 countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 925–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00083-3

Walters, S. J., Munro, J. F., & Brazier, J. E. (2001). Using the SF-36 with older adults: A cross-sectional community-based survey. Age and Ageing, 30(4), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/30.4.337

Wang, R., Wu, C., Zhao, Y., Yan, X., Ma, X., Wu, M., Liu, W., Gu, Z., Zhao, J., & He, J. (2008). Health related quality of life measured by SF-36: A population-based study in Shanghai. China. BMC Public Health, 8, 292. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-292

Wang, P., Chen, C., Yang, R., & Wu, Y. (2015). Psychometric evaluation of health related quality of life among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13, 155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0350-1

Ware, J. E., Jr. (1995). The status of health assessment 1994. Annual Review of Public Health, 16, 327–354.

Ware, J. E., Jr., & Gandek, B. (1994). The SF-36 Health Survey: Development and use in mental health research and the IQOLA Project. International Journal of Mental Health, 23(2), 49–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.1994.11449283

Ware, J. E., Jr., & Gandek, B. (1998). Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 903–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00081-x

Ware, J. E., Jr., & Gandek, B. (1998). Methods for testing data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability: the IQOLA Project approach. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of clinical epidemiology, 51(11), 945–952. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00085-7

Ware, J. E., Jr., & Sherbourne, C. D. (1992). The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care, 30(6), 473–483.

Ware, J. E., Jr., Snow, K. K., Kosinski, M., & Gandek, B. G. (1993). SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center: Boston,.

Ware, J. E., Jr., Kosinski, M., & Keller, S. D. (1994). SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Health Assessment Lab.

Ware, J. E., Jr, Kosinski, M., Gandek, B., Aaronson, N. K., Apolone, G., Bech, P., Brazier, J., Bullinger, M., Kaasa, S., Leplège, A., Prieto, L., & Sullivan, M. (1998). The factor structure of the SF-36 Health Survey in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1159–1165. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00107-3

Yanguas Lezaun, J. J. (2006). Análisis de la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en la vejez desde una perspectiva multidimensional (1era ed.). Instituto de Mayores y Servicios Sociales (IMSERSO).

Yesavage, J. A., Brink, T. L., Rose, T. L., Lum, O., Huang, V., Adey, M., & Leirer, V. O. (1982). Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4

Zúniga, M. A., Carrillo-Jiménez, G. T., Fos, P. J., Gandek, B., & Medina-Moreno, M. R. (1999). Evaluación del estado de salud con la Encuesta SF-36: Resultados preliminares en México [Evaluation of health status using Survey SF-36: Preliminary results in Mexico]. Salud Publica De Mexico, 41(2), 110–118.

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out as part of the project titled “Abuse in old age: prevalence and risk factors. A cohort study” (In Spanish: “Maltrato en la vejez: prevalencia y factores de riesgo. Un estudio de cohorte”), funded by the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACyT, for its acronym in Spanish) (CB-2016/287302). Our greatest appreciation to all the older persons who participated in the study, sharing their time and experiences. We also want to thank the researchers who were part of the fieldwork and to the authorities of the City Councils of Xalapa and Mexico City for their support.

Funding

The project was funded by the funded by the Mexican National Council of Science and Technology (CONACyT, for its acronym in Spanish) (CB-2016/287302). The authors received no additional financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent

The protocol was evaluated and approved by the Ethics in Research Committee and the Research Committee of the National Institute of Geriatrics (registration DI-PI-007/2018). Each participant who was invited to participate received a fact sheet about the project and had the opportunity to ask questions about it. Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants who agreed to participate. The project was funded by the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico (CONACyT, for its acronym in Spanish) the Call for Basic Scientific Research (CB-2016/287302).

Disclosures

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose, nor competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Giraldo-Rodríguez, L., López-Ortega, M. Validation of the Short‐Form 36 Health Survey (SF‐36) for use in Mexican older persons. Applied Research Quality Life 19, 269–292 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10240-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-023-10240-6