Abstract

Social media use has been associated with depression in youth. It remains unclear how individual differences in social media use and depression relate to other health-related behaviors such as physical activity, green space exposure, cannabis use, and eveningness. We aimed to examine these associations and network structure with the Green/Screen Study, a Canadian cohort of 425 adults (82.5% female) aged 18–25 years who completed three online questionnaires between May 2021 and January 2022. Longitudinal analyses showed sex differences in the association of social media use with depression. Although social media use was positively associated with depression after adjusting for other health-related behaviors, it did not predict an increase in depressive symptoms over time. Shorter time intervals and more detailed measures of social media use may be needed to capture social media context- and usage-specific associations with depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the past two decades, there has been a significant increase in the prevalence of depression in adolescents and young adults (Keyes & Platt, 2023; Yu et al., 2020). Simultaneously, there has been an unprecedented inclusion of technology in our daily social lives. Digital media use among adults in the United States (USA) has increased from 5 to 72% in only two decades (Pew Research Center, 2021) and newer generations of youth have experienced even higher rates of digital media use, with 95% of the adolescent population using digital media (Anderson & Jiang, 2018).

Social media is a subset of digital media that has become increasingly popular over the past two decades. The rates of social media use in the U.S. are 72% in the general population and 84% among youth aged 18 to 29 years, with similar rates in other countries, including Canada (Wike et al., 2022). There has been a recent increase in social media use during and post-COVID-19 pandemic, likely related to social isolation, boredom, and a desire for social connectedness (Avena et al., 2021). While causation has not been established, some researchers argue that the increased depression rates are at least partly attributable to the expansion of smartphone use among youth (Twenge & Campbell, 2018; Twenge et al., 2018). In the U.S., female-specific increases in rates of suicide (a possible outcome of severe depression), by 87% in girls aged 15–24 (Garnett et al., 2022) have mirrored increases in the use of social media platforms (Pew Research Center, 2023; Twenge et al., 2018). Many mechanisms have been hypothesized as potentially influencing the associations between social media use and depression, including cyberbullying, social contagion, increased opportunities for upward social comparisons (Vidal et al., 2020), and sleep disruption (Alonzo et al., 2021). Some studies in youth support a longitudinal association between social media use and depression and other emotional and behavioral problems (Boers et al., 2019; Riehm et al., 2019), especially when the time spent on social media is excessive (McNamee et al., 2021). Yet, other studies show no (Beeres et al., 2021; Coyne et al., 2020; Orben & Przybylski, 2019) or weak longitudinal associations (Heffer et al., 2019; Puukko et al., 2020).

Young adulthood is a key developmental period in the shaping of behaviors that can affect health later in life (Hawkins et al., 1992). One of the concerns with excessive use of social media is the displacement of other health-related behaviors, known to have positive effects on mental health, such as time outdoors and exposure to green spaces (Liu et al., 2023), sleep (Scott et al., 2021), and exercise (Pearce et al., 2022). Displacement theory postulates that social media use may directly have an effect on time spent away from physical activities, in-person socializing, or other health-promoting activities such as sleep and schoolwork, with potential negative impacts on the person’s mental health (Hall & Liu, 2022). Conversely, maintaining a healthy lifestyle can positively affect mental health (Maenhout et al., 2020).

While often studied separately, health-related behaviors are interrelated and associated with mental health outcomes. For example, eveningness, or the tendency to sleep late in the night and wake up late in the morning, has been associated with greater use of digital media, greater sedentary behaviors, and more depressive symptoms (Au & Reece, 2017; Patterson et al., 2016). The increase in social media use during the pandemic was associated with worse sleep patterns in students (Ali et al., 2022), and sleep contributes to the relationship between sedentary behaviors and mental health symptoms (Werneck et al., 2020). Situations leading to stress and isolation can further exacerbate behavioral and substance use disorders (Avena et al., 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, youth displayed an increase in sedentary behaviors, reduced physical activity, disrupted sleep patterns, and a change in dietary habits (Avena et al., 2021; Pérez-Carbonell et al., 2020); these changes were paralleled by increases in screen use and mental distress, either linked to these changes in habits, or due to other causes (Caroppo et al., 2021). Furthermore, environmental features, such as exposure to green spaces, may also contribute to depression. For example, a recent meta-analysis found lower risk of depression with a 10% increase in the proportion of residential green space (Liu et al., 2023). Finally, changes in cannabis regulation have been postulated to contribute to the increase in suicide rates among youth (Hammond et al., 2023), and there are well-known associations between cannabis and depression (Arias et al., 2020; Bolanis et al., 2020; Gobbi et al., 2019). Together, these interrelated behaviors may underlie some of the associations between social media use and depression.

Despite the growth in the number of longitudinal studies exploring the associations between social media use and depressive symptoms, the directionality and strength of association in the context of other risk and protective health-related behaviors need further exploration. The aim of this study was to examine the longitudinal and network associations between social media use and depression in youth after accounting for other health-related behaviors and sex differences.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that higher initial levels of social media use would be associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms over time, taking into consideration baseline levels of physical activity, green space exposure, cannabis use and eveningness, with a stronger association in female participants. To better understand how health-related behaviors relate to each other and with depressive symptoms, we further explored their interrelationships using network analyses.

Method

Participants

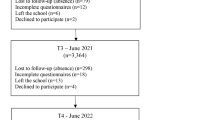

Participants were from the Green/Screen Study (https://osf.io/y2b9z/), a cohort of 425 (82.5% female) young adults (18–25 years) residing in the Canadian province of Québec and speaking one of the two official languages of the country, French or English.

Participants were recruited through advertisements targeting the aforementioned age range and geographical region through four popular social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Reddit) and two classified advertisement websites (Kijiji and Craigslist). Individuals were oriented to the study website for project information and consent. All participants provided their written consent electronically. Draws of 20 lots of $25 CAD after the first study time point and 10 lots of $100 CAD after the third time point were offered to increase participation and reduce attrition. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Quebec at Montreal (#4552_e_2021).

Measures

Participants were assessed over three time points during the following periods: May 27 to June 14, 2021 (T1), September 8 to October 13, 2021 (T2), and December 2 to January 11, 2022 (T3). Questionnaires were administered online through a custom survey platform (https://www.elaborer.org). At each time point, self-reported measures included depressive symptoms, social media use, greenspace exposure, physical activity, and cannabis use. Age, sex (male or female), educational attainment, and eveningness chronotype were measured at baseline.

Depressive symptoms were measured at each time point with the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001). The PHQ-9 consists of 9 questions related to symptoms of depression on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), with a total score ranging from 0 to 27.

Social media use was measured using the following item adapted from the Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (Nikolaidis et al., 2021): “During the past 3 months, how much time per day did you spend using social media (such as Facetime, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, TikTok)?”. Response options were “never/did not use”, “under 1 h”, “1–3 h”, “4–6 h”, and “more than 6 h.” To capture unequal distances between these response categories, they were re-coded as numeric values according to their midpoints: 0, 0.5, 2, 5, and 7 h per day, respectively.

Greenspace exposure was measured using two items adapted from Coldwell & Evans (Coldwell & Evans, 2018): “Over the last 3 months, how often did you visit outdoor spaces in the countryside (such as a forest, river or field)?” and “[…] how often did you visit outdoor green spaces in your city (such as a park, garden or canal)?”. For each item, response options were “Never”, “Once or twice”, “Every month”, “Every 2 weeks”, “Every week”, “Several times a week”, and “Daily”. These categories were re-coded numerically to indicate the average number of days of exposure per week. The two item scores (rural and urban green space exposure) were summed to obtain the total frequency of green space exposure (range, 0–7 days/week).

Physical activity was evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form (Craig et al., 2003). This questionnaire includes seven items measuring weekly time spent on low, moderate, and high-intensity physical activity. Responses are aggregated to estimate the total metabolic equivalent task (MET)—minutes/week.

Frequency of cannabis use in the past 2 weeks was reported on a 4-point scale (“never”, “1–2 times per week”, “3 or more times per week”, and “everyday”) (Landry et al., 2004). Due to skewed responses, cannabis use was dichotomized as any versus none in regression models.

Eveningness chronotype was measured by assessing typical sleep habits using the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (Roenneberg et al., 2003). As recommended by the questionnaire creators (Roenneberg et al., 2004), we calculated chronotype as the midsleep point on days without engagements (i.e., without work or school) and corrected for sleep debt accumulated during days with engagements. The midsleep point corresponds to the time of the day between the onset and end of the sleep period (range, 0–24 h). A higher value indicates greater eveningness, defined as the tendency to initiate sleep later in the night and to wake up later in the morning.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted in R version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021). Descriptive analyses were performed to report characteristics of the sample according to attrition status. To evaluate associations between social media use at T1 and depressive symptoms at T1, T2, and T3, we used linear mixed models with random intercepts. All models were adjusted for time (T1, T2, or T3), age, and sex. We subsequently included the other health-related behaviors at T1 (physical activity, greenspace exposure, cannabis use, and eveningness) as covariates. We explored sex differences by testing the interaction between sex and social media use. To evaluate whether higher social media use at T1 was associated with a trajectory of increasing depressive symptoms over time, we tested the interaction of time with social media use at T1. We used the same approach to evaluate whether depressive symptoms at T1 were associated with social media use over time. Confidence intervals of 95% not overlapping the null and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

To examine the network structure of associations between depressive symptoms, social media use, and other health-related behaviors, we generated Gaussian graphical models using the qgraph (Epskamp et al., 2012) and bootnet packages (Epskamp et al., 2018). In network models, variables are visually represented as nodes, and the connections between variables are represented as edges. Edges indicate partial correlations between any two nodes after conditioning on all the other nodes in the network. To estimate edge weights, we applied the ggmModSelect algorithm (stepwise estimation) given its good performance at low sample sizes (Isvoranu & Epskamp, 2023), and we used the Spearman correlations to accommodate non-parametric associations. With ggmModSelect, the inclusion or removal of edges from the network is based on minimizing the extended Bayesian information criterion. We generated separate cross-sectional models for data at T1, T2, and T3, restricting the analyses to participants with complete data on network variables at each time point. Because chronotype is thought to be stable over time and was only measured at T1, we used the same measure for subsequent time points. Non-parametric bootstrapping with 1000 iterations was performed to evaluate the accuracy of network estimates at T1. Edge weights were considered significant if they were not set to zero in > 50% of non-parametric bootstrapped models. Bootstrap analyses were not performed on networks at T2 and T3 given smaller sample sizes. Codes are available at https://osf.io/y2b9z/.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Sample characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and S1. The analytic sample included 376 participants who had complete data on all measures at T1. Of this sample, 233 (62.0%) completed at least one of the follow-up assessments (T2 or T3). These participants, compared with those who only completed T1 assessments, were more likely to be female and less likely to use cannabis and reported fewer depressive symptoms.

Longitudinal Depressive Symptoms as a Function of Social Media Use at T1

Greater social media use at T1 was associated with more depressive symptoms on average over T1, T2, and T3 (Table 2). The association remained significant after adjusting for other health-related behaviors at T1. Cannabis use and greater eveningness were also associated with more depressive symptoms. Sex, greenspace exposure, and physical activity were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms tended to increase over time, but the slope of time was not statistically significant.

The interaction between social media use and time was not significant: coefficient = − 0.86 (95% CI, − 0.244, 0.071), indicating that greater social media use at T1 was not associated with an increase or decrease in depressive symptoms over time (Fig. 1). There was however a significant interaction of social media use with sex: coefficient = − 0.785 (95% CI, − 1.434, − 0.136). In female participants, social media use at T1 was significantly associated with more depressive symptoms on average: coefficient = 0.551 (95% CI, 0.264, 0.838). The coefficient indicates that for each additional hour of social media use at T1, depressive symptoms were higher by ~ 0.5 point on the PHQ-9. In male participants, this association was in the opposite direction and not significant: coefficient = − 0.234 (95% CI, − 0.821, 0.353).

Longitudinal Social Media Use as a Function of Depressive Symptoms at T1

More depressive symptoms at T1 were associated with greater social media use on average over T1, T2, and T3 (Table 3). The association remained significant after adjusting for other health-related behaviors at T1. Greater greenspace exposure at T1 was associated with less social media use. Social media use significantly decreased over time. Sex, physical activity, cannabis use, and eveningness chronotype at T1 were not significantly associated with social media use. Interactions of depressive symptoms with time (coefficient = − 0.008 [95% CI, − 0.033, 0.018]) and sex (coefficient = − 0.066 [95% CI, − 0.144, 0.012]) were not significant.

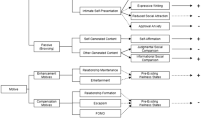

Network Associations

The network model of variables at T1 is presented in Fig. 2. The network identified direct associations of higher levels of social media use with higher levels of depressive symptoms and with lower levels of green space exposure. Other factors associated with higher depression included cannabis use, higher eveningness, and lower greenspace exposure. Physical activity was not directly associated with depression but shared an indirect relationship through its positive association with greenspace exposure. In non-parametric bootstrap analyses, the network edges differed from zero over most iterations (proportion of null estimates ≤ 0.5), supporting their robustness (Table S2; Figures S1-S2).

Network models at T2 and T3 identified fewer associations (Fig. 3). At both T2 and T3, there was an association between greater social media use and more depression, as well as between more physical activity and greater greenspace exposure. At T2, there was also an association between greater social media use and less greenspace exposure (as found at T1). At T3, this association was not present; however, there was an association between greater greenspace exposure and less depression (as found at T1). Other associations were not supported.

Network model of cross-sectional associations between depressive symptoms, social media use, and other measures at T2 and T3. Complete data, n = 218 at T2 (left) and n = 184, T3 (right). Blue edges indicate positive associations, and red edges indicate negative associations. Thicker edges indicate greater absolute edge weights. Depressive symptoms (range, 0-27); S, social media use (hours/day); P, physical activity (MET-minutes/week); G, frequency of green space exposure (range, 0–7 days/week); C, frequency of cannabis use (range, 0–7 days/week); E, eveningness chronotype (range, 0–24)

Discussion

This study found that greater social media use was associated with higher levels of depression in female young adults, even after controlling for other health-related behaviors at baseline. However, greater use of social media at baseline was not associated with an increase or decrease in depressive symptoms over time. These results show that social media use and depression are associated, supporting the notion that greater social media use may be a marker or correlate of concurrent depressive symptoms, but do not provide evidence that social media use is prospectively related to the course of depressive symptoms. The network analysis identified direct connections of higher levels of social media use with higher levels of depressive symptoms and with lower levels of green space exposure. Cannabis use, higher eveningness, and less greenspace exposure were also associated with more depressive symptoms at T1. These results highlight the interrelation of depression and behavioral and environmental factors in young adults, with potential implications for the early detection of depression and for lifestyle interventions in this population.

The association between greater social media use and higher levels of depression is consistent with previous research. Between-person associations indicate that those individuals with greater digital media use, including social media use, tend to experience more depression. Some studies have also identified within-person associations between changes in digital media use and changes in depression and vice versa, offering stronger evidence for causal effects as participants are compared with themselves, controlling for other individual characteristics, measured or not (Orben et al., 2022). Other studies, however, have found minimal or no association at the within-person level, leading to uncertainty about the true magnitude of effects of digital media use on youth mental health (Houghton et al., 2018; Orben et al., 2019; Steinsbekk et al., 2023). Interventions such as a brief abstinence period, an approach borrowed from substance use therapeutic interventions, have been suggested to improve mental health outcomes, with some experimental evidence of improvements in well-being, mood, and anxiety after 1 to 2-week periods of abstinence (Hunt et al., 2018; Lambert et al., 2022). However, other research has found no evidence of increased well-being with these “digital detoxes” (Przybylski et al., 2021).

Contrary to our hypothesis, adjusting for other health-related behaviors did not explain the association between social media use and depression, which may be influenced by yet other factors. In some individuals, neurobiological factors may predispose to higher social media use and depression, or mediate the relationship between the two (Becker et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2017) in youth with high screen exposure. For example, increased positive functional connectivity between the striatum and the frontal executive network has been associated with higher efficiency in inhibitory control during development (Liston et al., 2006; Rubia et al., 2006), which could be a shared correlate of social media use and mental health. Socio-environmental factors, including lower socioeconomic status, racialized minority status, and individual exposure to social adversity may also be shared risk factors for excessive social media use and mental health problems (Nagata et al., 2022).

Other associations in the network pointed to research directions for intervention in young adults. Higher exposure to green spaces was associated with lower levels of depression at T1 and T3. However, in the longitudinal models, greenspace exposure was not significantly associated with average depressive symptoms across T1, T2, and T3. There is extensive research on green spaces and health (Zhang, J. et al., 2020a). Despite relatively less research on mental health specifically, and heterogeneity in the outcome measures used, cumulative evidence points towards an association between positive mental health outcomes and green spaces (Bezold et al., 2018; Engemann et al., 2019; Gascon et al., 2015; Zhang, Y. et al., 2020b). In a randomized-controlled study of 37 adults with major depressive disorder, a single 60-min walk in nature was associated with an improvement in negative affect relative to an urban walk (Watkins-Martin et al., 2022). The lack of consistent associations of greenspace exposure with depression in the present study may stem from various factors, including overall low levels of depression in the sample (compared to clinical populations) and the impact of 3-month intervals between time points, which may be too long to capture momentary effects of health-related behaviors.

Physical activity was not directly associated with longitudinal depressive symptoms, but it was indirectly related to depression via green space exposure in the network models. One concern raised by the World Health Organization (WHO) (World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2020) is that the increase in screen time could replace healthy behaviors such as physical activity and sleep. A population-level prospective cohort study in the UK found that theoretically replacing 1 h of social media use with a team sport was associated with reductions in emotional distress scores (Kandola et al., 2022). National guidelines on physical activity recommend 150 min of moderate intensity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity weekly or an equivalent combination, as well as limited sedentary time (Piercy et al., 2018). In the U.S., sedentary behavior significantly increased from 2007 to 2016, coinciding with an increase in smartphone ownership (Du et al., 2019). Sedentary behavior has implications for mental health (Gibson et al., 2017), independent of the amount of physical activity (Bankoski et al., 2011; Maher et al., 2013; Zhai et al., 2015). In the present study, it is likely that those who spent more time doing physical activity or visiting green spaces, and less time on social media, were also less sedentary.

The association of eveningness with depression in the network analysis at T1 is consistent with previous research. A cross-sectional study in a non-clinical sample identified associations between eveningness and depression, mediated by affect and behavioral activation (Hasler et al., 2010). In the present network model, eveningness was not directly associated with social media use, but it was found elsewhere to be cross-sectionally associated with greater computer use (Patterson et al., 2016). Given the associations of eveningness with depression and cannabis use in the present network results, it is possible that eveningness is only indirectly associated with social media use via these other factors. The lack of association involving eveningness in network models at T2 and T3 may be due to the lower sample size, which constrained statistical power.

This study in part supports the displacement theory, as it shows that greater social media use was associated with less time spent in green spaces. The types of activities being displaced by social media may vary. For example, a study of youth undergoing abstinence found that abstinence from social media increased time engaged in other activities such as working, cooking, or cleaning (Hall et al., 2019). Social media may also be a substitute for other types of screen time (Hall & Liu, 2022). While social media use may displace certain activities, it may also amplify or increase other exposures, such as those related to interpersonal relationships, both positive and negative. As our study did not assess the types and contents of social media use, we could not examine their differential content and engagement effects, which may be more important than the overall time spent on social media (Morningstar et al., 2023).

Overall, the findings support the interrelationship of health-related behaviors, which is important to consider in future research given that various health-related behaviors may be correlates or predisposing factors for social media use and mental health outcomes. However, these findings do not provide evidence that greater social media use predicts increasing depressive symptoms over time. The lack of a longitudinal association between social media use at T1 and changes in depression across time may suggest that time spent on social media is more a marker of than a cause of depression, meaning that those people with a tendency to become depressed may be also more likely to use social media and vice-versa. Other factors may explain this association, such as pre-existing mental health, behavioral, and environmental factors. Importantly, associations between social media use and depression are also likely to vary depending on the types of content and actions that are accessed via social media. Specific aspects of social media use may have positive or negative impacts on depression, and these aspects may manifest to different degrees between individuals and over time. Our findings highlight the importance of taking an integrative approach when examining social media use and health-related behaviors, with the promotion of healthy behaviors as a potential intervention to be investigated in future research to address the various factors that could impact depression in tandem with social media use.

Limitations of this study include convenience sampling and the reliance on self-reported data. More “objective” measures of health-related behaviors may be obtained with digital phenotyping, a method of data collection that can include logs of social media use, sleep indices, and geolocation, via the use of smartphones or wearables. Importantly, we lacked data on the different types and contents of social media that were used, which may be differentially associated with depressive symptoms and other health-related behaviors. Lastly, the present sample was relatively small, which limited statistical power and the reliability of network estimates. Due to online convenience sampling, the sample included a majority of female individuals, further limiting the generalizability of the results to the general population. Attrition, which was predicted by male sex, cannabis use, and more depressive symptoms at baseline, may have influenced the regression (if data was missing not at random) and network estimates.

In conclusion, this study found concurrent associations of higher social media use with higher depression scores, as well as with other health-related behaviors including less time spent in green spaces. Despite their interrelationship, health-related behaviors may not be sufficient to explain the association between social media use and depression, which may instead reflect the influence of other individual, media-related, and socio-environmental factors.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the last author, Vincent Paquin (vincent.paquin2@mail.mcgill.ca), upon reasonable request.

References

Ali, A., Siddiqui, A. A., Arshad, M. S., Iqbal, F., & Arif, T. B. (2022). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on lifestyle and mental health of students: A retrospective study from Karachi. Pakistan. Annales Médico Psychologiques, 180(6), S29–S37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2021.02.004

Alonzo, R., Hussain, J., Stranges, S., & Anderson, K. K. (2021). Interplay between social media use, sleep quality, and mental health in youth: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 56, 101414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2020.101414

Anderson, M., & Jiang, J. (2018). Teens, social media & technology 2018. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from Social Science Premium Collection Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2063163964

Arias, A. J., Hammond, C. J., Burleson, J. A., Kaminer, Y., Feinn, R., Curry, J. F., & Dennis, M. L. (2020). Temporal dynamics of the relationship between change in depressive symptoms and cannabis use in adolescents receiving psychosocial treatment for cannabis use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 117, 108087. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108087

Au, J., & Reece, J. (2017). The relationship between chronotype and depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218, 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.021

Avena, N. M., Simkus, J., Lewandowski, A., Gold, M. S., & Potenza, M. N. (2021). Substance use disorders and behavioral addictions during the COVID-19 pandemic and COVID-19-related restrictions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 653674. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.653674

Bankoski, A., Harris, T. B., McClain, J. J., Brychta, R. J., Caserotti, P., Chen, K. Y., . . . Koster, A. (2011). Sedentary activity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of physical activity. Diabetes Care, 34(2), 497–503. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-0987

Becker, A., Kirsch, M., Gerchen, M. F., Kiefer, F., & Kirsch, P. (2017). Striatal activation and frontostriatal connectivity during non-drug reward anticipation in alcohol dependence. Addiction Biology, 22(3), 833–843. https://doi.org/10.1111/adb.12352

Beeres, D. T., Andersson, F., Vossen, H. G. M., & Galanti, M. R. (2021). Social media and mental health among early adolescents in Sweden: A longitudinal study with 2-year follow-up (KUPOL study). Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(5), 953–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.042

Bezold, C. P., Banay, R. F., Coull, B. A., Hart, J. E., James, P., Kubzansky, L. D., . . . Laden, F. (2018). The relationship between surrounding greenness in childhood and adolescence and depressive symptoms in adolescence and early adulthood. Annals of Epidemiology, 28(4), 213–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.01.009

Boers, E., Afzali, M. H., Newton, N., & Conrod, P. (2019). Association of screen time and depression in adolescence. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(9), 853–859. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1759

Bolanis, D., Orri, M., Castellanos-Ryan, N., Renaud, J., Montreuil, T., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., Tremblay, R. E., Turecki, G., Côté, S. M., Séguin, J. R., & Geoffroy, M. (2020). Cannabis use, depression and suicidal ideation in adolescence: direction of associations in a population based cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 1076–1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.136

Caroppo, E., Mazza, M., Sannella, A., Marano, G., Avallone, C., Claro, A. E., . . . Sani, G. (2021). Will nothing be the same again?: Changes in lifestyle during COVID-19 pandemic and consequences on mental health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(16), 8433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168433

Coldwell, D. F., & Evans, K. L. (2018). Visits to urban green-space and the countryside associate with different components of mental well-being and are better predictors than perceived or actual local urbanisation intensity. Landscape and Urban Planning, 175, 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2018.02.007

Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A. A., Zurcher, J. D., Stockdale, L., & Booth, M. (2020). Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 104, 106160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106160

Craig, C. L., Marshall, A. L., Sjöström, M., Bauman, A. E., Booth, M. L., Ainsworth, B. E., . . . Oja, P. (2003). International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 35(8), 1381–1395. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB

Du, Y., Liu, B., Sun, Y., Snetselaar, L. G., Wallace, R. B., & Bao, W. (2019). Trends in adherence to the physical activity guidelines for Americans for aerobic activity and time spent on sedentary behavior among US adults, 2007 to 2016. JAMA Network Open, 2(7), e197597. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7597

Engemann, K., Pedersen, C. B., Arge, L., Tsirogiannis, C., Mortensen, P. B., & Svenning, J. (2019). Residential green space in childhood is associated with lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(11), 5188–5193. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1807504116

Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04

Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1

Garnett, M., Curtin, S., & Stone, D. (2022). Suicide mortality in the United States, 2000–2020. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.). https://doi.org/10.15620/cdc:114217. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db433.htm

Gascon, M., Triguero-Mas, M., Martínez, D., Dadvand, P., Forns, J., Plasència, A., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2015). Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(4), 4354–4379. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120404354

Gibson, A., Muggeridge, D. J., Hughes, A. R., Kelly, L., & Kirk, A. (2017). An examination of objectively-measured sedentary behavior and mental well-being in adults across week days and weekends. PLoS ONE, 12(9), e0185143. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185143

Gobbi, G., Atkin, T., Zytynski, T., Wang, S., Askari, S., Boruff, J., . . . Mayo, N. (2019). Association of cannabis use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in young adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 76(4), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4500

Hall, J. A., & Liu, D. (2022). Social media use, social displacement, and well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, 101339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101339

Hall, J. A., Johnson, R. M., & Ross, E. M. (2019). Where does the time go? an experimental test of what social media displaces and displaced activities’ associations with affective well-being and quality of day. New Media & Society, 21(3), 674–692. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818804775

Hammond, C. J., Hyer, J. M., Boustead, A. E., Fristad, M. A., Steelesmith, D. L., Brock, G. N., Hasin, D. S., & Fontanella, C. A. (2023). Association between marijuana laws and suicide among 12- to 25-year-olds in the United States from 2000 to 2019. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, S0890-8567(23)00341-6. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2023.06.014

Hasler, B. P., Allen, J. J. B., Sbarra, D. A., Bootzin, R. R., & Bernert, R. A. (2010). Morningness–eveningness and depression: Preliminary evidence for the role of the behavioral activation system and positive affect. Psychiatry Research, 176(2), 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.06.006

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Miller, J. Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 64–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64

Heffer, T., Good, M., Daly, O., MacDonell, E., & Willoughby, T. (2019a). The longitudinal association between social-media use and depressive symptoms among adolescents and young adults: An empirical reply to Twenge et al. (2018). Clinical Psychological Science. 7(3):462–470. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618812727

Houghton, S., Lawrence, D., Hunter, S. C., Rosenberg, M., Zadow, C., Wood, L., & Shilton, T. (2018). Reciprocal relationships between trajectories of depressive symptoms and screen media use during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(11), 2453–2467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0901-y

Hunt, M. G., Marx, R., Lipson, C., & Young, J. (2018). No more FOMO: Limiting social media decreases loneliness and depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(10), 751–768. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.10.751

Isvoranu, A. M., & Epskamp, S. (2023). Which estimation method to choose in network psychometrics? Deriving guidelines for applied researchers. Psychological Methods, 28(4), 925–946. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000439

Kandola, A., del Pozo Cruz, B., Hayes, J. F., Owen, N., Dunstan, D. W., & Hallgren, M. (2022). Impact on adolescent mental health of replacing screen-use with exercise: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 301, 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.064

Keyes, K. M., & Platt, J. M. (2023). Annual research review: Sex, gender, and internalizing conditions among adolescents in the 21st century - trends, causes, consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines,. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13864.Advanceonlinepublication

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine : JGIM, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Lambert, J., Barnstable, G., Minter, E., Cooper, J., & McEwan, D. (2022). Taking a one-week break from social media improves well-being, depression, and anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 25(5), 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0324

Landry, M., Tremblay, J., Guyon, L., Bergeron, J., & Brunelle, N. (2004). La Grille de dépistage de la consommation problématique d’alcool et de drogues chez les adolescents et les adolescentes (DEP-ADO): Développement et qualités psychométriques. Drogues, Santé Et Société, 3(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.7202/010517ar

Liston, C., Watts, R., Tottenham, N., Davidson, M. C., Niogi, S., Ulug, A. M., & Casey, B. J. (2006). Frontostriatal microstructure modulates efficient recruitment of cognitive control. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N.Y. 1991), 16(4), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhj003

Liu, Z., Chen, X., Cui, H., Ma, Y., Gao, N., Li, X., . . . Liu, Q. (2023). Green space exposure on depression and anxiety outcomes: A meta-analysis. Environmental Research, 231(Pt 3), 116303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2023.116303

Maenhout, L., Peuters, C., Cardon, G., Compernolle, S., Crombez, G., & DeSmet, A. (2020). The association of healthy lifestyle behaviors with mental health indicators among adolescents of different family affluence in Belgium. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–958. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09102-9

Maher, C. A., Mire, E., Harrington, D. M., Staiano, A. E., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2013). The independent and combined associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior with obesity in adults: NHANES 2003‐06. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 21(12), E730-E737. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20430

McNamee, P., Mendolia, S., & Yerokhin, O. (2021). Social media use and emotional and behavioural outcomes in adolescence: Evidence from British longitudinal data. Economics and Human Biology, 41, 100992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.100992

Morningstar, B., Clayborne, Z., Wong, S. L., Roberts, K. C., Prince, S. A., Gariépy, G., . . . Lang, J. J. (2023). The association between social media use and physical activity among Canadian adolescents: A health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 114(4), 642–650. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-023-00754-9

Nagata, J. M., Singh, G., Sajjad, O. M., Ganson, K. T., Testa, A., Jackson, D. B., . . . Baker, F. C. (2022). Social epidemiology of early adolescent problematic screen use in the United States. Pediatric Research, 92(5), 1443–1449. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-022-02176-8

Nikolaidis, A., Paksarian, D., Alexander, L., Derosa, J., Dunn, J., Nielson, D. M., . . . Merikangas, K. R. (2021). The coronavirus health and impact survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 8139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87270-3

Orben, A., & Przybylski, A. K. (2019). Screens, teens, and psychological well-being: Evidence from three time-use-diary studies. Psychological Science, 30(5), 682–696. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619830329

Orben, A., Dienlin, T., & Przybylski, A. K. (2019). Social media’s enduring effect on adolescent life satisfaction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS, 116(21), 10226–10228. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1902058116

Orben, A., Przybylski, A. K., Blakemore, S., & Kievit, R. A. (2022). Windows of developmental sensitivity to social media. Nature Communications, 13(1), 1649. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29296-3

Patterson, F., Malone, S. K., Lozano, A., Grandner, M. A., & Hanlon, A. L. (2016). Smoking, screen-based sedentary behavior, and diet associated with habitual sleep duration and chronotype: Data from the UK Biobank. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(5), 715–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9797-5

Pearce, M., Garcia, L., Abbas, A., Strain, T., Schuch, F. B., Golubic, R., . . . Woodcock, J. (2022). Association between physical activity and risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 79(6), 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0609

Pérez-Carbonell, L., Meurling, I. J., Wassermann, D., Gnoni, V., Leschziner, G., Weighall, A., . . . Steier, J. (2020). Impact of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on sleep. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 12(Suppl 2), S163-S175. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-cus-2020-015

Pew Research Center (2021). Social Media Fact Sheet. (April 7, 2021) Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/

Pew Research Center. (2023). Teens, social media and technology 2023.

Piercy, K. L., Troiano, R. P., Ballard, R. M., Carlson, S. A., Fulton, J. E., Galuska, D. A., . . . Olson, R. D. (2018). The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association, 320(19), 2020–2028. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14854

Przybylski, A. K., Nguyen, T. T., Law, W., & Weinstein, N. (2021). Does taking a short break from social media have a positive effect on well-being? Evidence from three preregistered field experiments. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 6(3), 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41347-020-00189-w

Puukko, K., Hietajärvi, L., Maksniemi, E., Alho, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2020). Social media use and depressive symptoms—A longitudinal study from early to late adolescence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5921. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165921

R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org

Riehm, K. E., Feder, K. A., Tormohlen, K. N., Crum, R. M., Young, A. S., Green, K. M., . . . Mojtabai, R. (2019). Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. Archives of General Psychiatry, 76(12), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2325

Roenneberg, T., Wirz-Justice, A., & Merrow, M. (2003). Life between clocks: Daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. Journal of Biological Rhythms, 18(1), 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748730402239679

Roenneberg, T., Kuehnle, T., Pramstaller, P. P., Ricken, J., Havel, M., Guth, A., & Merrow, M. (2004). A marker for the end of adolescence. Current Biology, 14(24), R1038–R1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.039

Rubia, K., Smith, A. B., Woolley, J., Nosarti, C., Heyman, I., Taylor, E., & Brammer, M. (2006). Progressive increase of frontostriatal brain activation from childhood to adulthood during event-related tasks of cognitive control. Human Brain Mapping, 27(12), 973–993. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20237

Scott, A. J., Webb, T. L., Martyn-St James, M., Rowse, G., & Weich, S. (2021). Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 60, 101556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101556

Steinsbekk, S., Nesi, J., & Wichstrøm, L. (2023). Social media behaviors and symptoms of anxiety and depression A four-wave cohort study from age 10–16 years. Computers in Human Behavior, 147, 107859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107859

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617723376

Vidal, C., Lhaksampa, T., Miller, L., & Platt, R. (2020). Social media use and depression in adolescents: A scoping review. International Review of Psychiatry (abingdon, England), 32(3), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1720623

Watkins-Martin, K., Bolanis, D., Richard-Devantoy, S., Pennestri, M., Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Philippe, F.,Guindon, J., Gouin, J., Ouellet-Morin, I., & Geoffroy, M. (2022). The effects of walking in nature on negative and positive affect in adult psychiatric outpatients with major depressive disorder: A randomized-controlled study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 318, 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.08.121

Werneck, A. O., Silva, D. R., Malta, D. C., Lima, M. G., Souza-Júnior, P. R. B., Azevedo, L. O., . . . Szwarcwald, C. L. (2020). The mediation role of sleep quality in the association between the incidence of unhealthy movement behaviors during the COVID-19 quarantine and mental health. Sleep Medicine, 76, 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.09.021

Wike, R., Silver, L., Fetterolf, J., Huang, C., Austin, S., Clancy, L., & Gubbala, S. (2022). Social media seen as mostly good for democracy across many nations, but U.S. is a major outlier. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/12/PG_2022.12.06_Online-Civic-Engagement_REPORT.pdf

World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. (2020). Excessive screen use and gaming considerations during COVID19 World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Retrieved from: https://www.emro.who.int/mnh/news/considerations-for-young-people-on-excessive-screen-use-during-covid19.html

Yu, B., Zhang, X., Wang, C., Sun, M., Jin, L., & Liu, X. (2020). Trends in depression among adults in the United States, NHANES 2005–2016. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 609–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.036

Yuan, K., Yu, D., Bi, Y., Wang, R., Li, M., Zhang, Y., . . . Tian, J. (2017). The left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and caudate pathway: New evidence for cue‐induced craving of smokers. Human Brain Mapping, 38(9), 4644–4656. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23690

Zhai, L., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, D. (2015). Sedentary behaviour and the risk of depression: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(11), 705–709. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-093613

Zhang, Y., Mavoa, S., Zhao, J., Raphael, D., & Smith, M. (2020a). The association between green space and adolescents’ mental well-being: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6640. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186640

Zhang, J., Yu, Z., Zhao, B., Sun, R., & Vejre, H. (2020b). Links between green space and public health: A bibliometric review of global research trends and future prospects from 1901 to 2019. Environmental Research Letters, 15(6), 63001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab7f64

Funding

This study received funding from the Stratas Foundation awarded to Dr. Paquin. Dr. Vidal receives funding from the NIDA/AACAP Physician Scientist Training Program in Substance Abuse Research, supported by NIDA Career Development Award (K12DA000357). Dr. Geoffroy holds a Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) in Youth Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. Dr. Paquin is supported by an award from the Quebec Network on Suicide, Mood Disorders and Associated Disorders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Vidal, C., Philippe, F.L., Geoffroy, MC. et al. The Role of Social Media Use and Associated Risk and Protective Behaviors on Depression in Youth Adults: A Longitudinal and Network Perspective. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01313-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-024-01313-0