Abstract

In this essay I elaborate on three ideas that emerged from reading the work of Sylvie Barma. These points are in response to curriculum reform and the use of activity theory: (a) curriculum reform as a public policy; (b) a reflection about the process followed by teacher implementation of that reform in a biology classroom; and (c) the sense of experience as an objective anchored in activity theory. This commentary deals with several entanglements of science teaching and learning where I am also able to address some of my own queries in the use of activity theory in research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Resúmen ejecutivo

A partir del ensayo titulado, “Una lectura sociocultural de la Reforma en la enseñanza de la ciencia en una clase de Biología en el nivel secundaria” presentado por Sylvia Barma, planteamos una serie de argumentos centrados en los siguientes temas: (a) una crítica a las reformas curriculares en tanto política pública; (b) una reflexión relativa al proceso seguido por la investigadora al valorar la implementación de esa reforma en una aula de Biología; y (c) la construcción del sentido en sus objetivos basados en la Teoría de la Actividad.

La perspectiva desde donde se elaboran estas apreciaciones parte de una pregunta inicial, ¿Qué es lo social en la teoría sociocultural? Es decir, ¿cómo se percibe este trabajo de vinculación de los componentes sociales y culturales en el manuscrito de Barma? Para abordar estas interrogantes, recurrimos a los fundamentos sociológicos de la Teoría de Campo Social de Pierre Bourdieu. Se hace de esta forma para encontrar los puntos en común entre ambas teorías. Con este ejercicio de Interdisciplina, se realiza un análisis de la información proporcionada por la autora desde otra perspectiva de lo social, que suponemos aporta una nueva lectura, complementaria, de los procesos, motivos, objetos y resultados, para la teoría de la actividad.

Esta primera lectura desde P. Bourdieu, nos llevó a reflexionar acerca del proceso seguido por S. Barma relativo a los componentes, emocionales, sociales y cognitivos que le otorgan sentido a la experiencia. Para esto recurrimos al concepto elaborado por Vygotsky para esta compleja configuración: perezhivanie. En otras palabras, la documentación del proceso seguido por la maestra de Biología Catherine, en un inicio nos habilitó para construir una explicación complementaria a los hallazgos de S. Barma, tanto como un agente desplegando sus disposiciones en el espacio social, también en el campo de producción cultural de una política pública y finalmente en el espacio social constituido por su propia trayectoria docente, su experiencia en la clase de Biología y su forma de proceder durante la investigación. A partir de lo anterior es factible reconocer la posición que Catherine ocupa en estos espacios sociales y comprender sus modalidades de participación durante el proceso documentado.

Sin embargo en una segunda lectura del texto, también reconstruimos algunas de las tensiones implícitas en el reporte de S. Barma, pero que desde esa lectura inicial, hacían que su posición como investigadora, también se hiciera explícita. Es decir, la forma en que el vínculo entre las tensiones de una política pública y el trabajo en el aula de Biología, pueden ser vistas como el marco que nos explica las otras tensiones: la profesora ante la reforma y la profesora ante la investigadora. En un tercer momento la reflexión llevó a considerer al proceso de objetivación del sujeto que investiga, ya que la teoría de la actividad promueve como un valor central, la estimulación de rangos de conciencia mayores en aquellos agentes que la emplean. Nos referimos a las posiciones y disposiciones de Catherine y Sylvie vistas de manera relacional, en un primer marco, y cómo a partir de la tensión generada en este vincula pudimos comprender la forma en que Sylvie reporta los resultados de la campaña realizada por Catherine con su grupo de estudiantes en el curso de Biología.

Finalmente, esta serie de reflexiones nos permitió plantear, desde Vygotsky, el problema de la experiencia como condensación de componentes tanto cognitivos como estructurales; tanto individuales como los derivados de la posición en el campo que ocupan los agentes involucrados en la investigación de Barma. En este sentido el concepto de perezhivanie nos parece de una gran potencialidad en el momento en que empleamos la teoría de la actividad. Nos ofrece una perspectiva sociocultural más comprometida con las aportaciones de la sociología crítica, un lectura del proceso en la construcción del conocimiento realizado por un investigador, y una punto de vista para reflexionar sobre el sentido y la construcción de significados y experiencia de cualquier empresa humana.

Espero que esta lectura multiple y de secuencia recursiva permita a los lectores seguir el razonamiento realizado desde una perezhivanie particular y que, asimismo, transmita la posibilidad de una comprensión compartida por y desde la perezhivanie del lector.

This commentary offers the space to discuss different possible readings and theoretical reflection over the practical implications that sociocultural perspectives provide to the learning and teaching of science. I hope that the discussion of Sylvie Barma’s work could clarify three humdrums I have found not only in this text, but also within a broader consideration of social and sociological perspectives implicated in curriculum reform as a field of cultural production. I also wish to clarify my personal perspectives from which this commentary emerges around activity theory.

The interpretation of a sociocultural theory is assigned or appropriated by the historical traditions in which the reader is immersed. Acknowledging this fact, the interpretations of the activity theory, in liberal sectors from Latin America, emphasize relationships between agent and structure in a more hard way than elsewhere. Thus, the intent is twofold: first, to link a relational thinking from Pierre Bourdieu and, second, to relate this to the concept of experience (perezhivanie) from Vygotsky, thus taking both as a searching to contribute within and considering reform in science education as a field of cultural production in a sociological theory. From a relational point of view Bourdieu captures the tone of my commentary:

[C]onstructing an object, such as [this] requires and enables us to make a radical break with the substantialist mode of thought which tends to foreground the individual, or the visible interaction between individuals, at the expense of the structural relations- invisible, or visible only through their effects- between social positions that are both occupied and manipulated by social agents which may be isolated individuals, groups or institutions. (Bourdieu 1993, p. 31)

I hope to show the pertinence of this statement regarding my reading of Barma’s study and her conclusions. This commentary deals with several entanglements of science teaching and learning: (a) curriculum reform as a public policy; (b) a reflection about the process followed by research in a teacher’s implementation of such reform in a biology classroom; and (c) the sense of experience as an objective anchored in activity theory. In this essay I elaborate on each of these.

Looking for the unit of analysis: curriculum reform as a public policy

What would happen if we consider science education curriculum reform as a field of socioculturally anchored practice? One major assumption regarding curriculum reform relies on the fact that the new proposals are better than the reality they pursue to change, also that they will find several forms of opposition in their attempt. As an anchored practice, this implies that I first clarify what social means in this field.

Beginning with the core goal of this reform, who could deny that “health and well-being, career planning and entrepreneurship, environmental awareness and consumer rights and responsibilities, media literacy, and citizenship and community life” are not worthy? But within the field of curriculum reform, which frequently means curricular standardization towards employability, this is anything but a plain or simple field to understand and to make change. Here, any curriculum reform, beyond their ideals and objectives for change, is also a field of cultural production and reproduction in which the social aims can no longer be seen as isolated from economical [societal] goals (Straume 2011).

Sylvie Barma quotes “the introduction of new practices is an outcome of the process of resolving the tensions occurring among organizations” and “such tensions may stem from the implementation of a new curriculum in the context of school reform.” From a relational starting point, it is not impossible to identify that in this organization of curriculum reform, one deals with the Economic Cooperation and Development while another concerns Education, Research and Teaching systems. Looking for the unit of analysis, the author overlooks the first quote—“the introduction of new practices is an outcome of the process of resolving the tensions occurring among organizations” and assumes the second—“such tensions may stem from the implementation of a new curriculum in the context of school reform.” In this relational venue, a reform in curriculum involves social and cultural as well an economic reform, thus the societal outcome dimension in activity theory. Though a causality relation, tensions emerge in different forms, but as a relational field the previous existing tensions express themselves, that is, a curriculum reform is an opportunity to liberate, and manifest what was latent. This is because activity theory is simultaneously social and historical, not only biographical or anecdotal.

At the first level, the intent of reform is to achieve this change—that is, social, cultural and economic—that leads to the pursuit of the reform. Either way, there exists tension among organizations and their implementation of school reform, making the two indissolubly related. In both ways the tensions are among organizations. At another level, this tension expresses itself in the school context. The relevance of Barma’s research allows me to reflect on the outcomes of her research on these two levels.

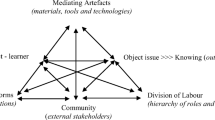

In this way she declares a previous interest in “… how the members of an educational community (or the teachers in particular) managed to work and facilitate renewed science teaching practices in a school that subscribed to the principles underlying a reform of science education curricula.” However, when she selects the unit of analysis, Barma deals with the first assumption—that is, the tension created at the boundaries of organization standards on Teaching and Learning Situation (TLS) and a new practice and curriculum reform driven by the Quebec Education Program dedicated to Science and Technology. They advocate for practices looking at the central role played by the organization or institutional prescription of TLS, mainly in the form of lecture-based classrooms, evaluating concepts and experimental protocols. According to Daniels (2008) and his description of activity theory, the “third generation posit networks of activities and this is currently being developed to take account of some of the complexities of the boundaries that are created and transgressed between multiple activities in practice” (p. 121).

From the relational thinking, advised Bourdieu, if we address our attention between the tensions due to the arrivals of a new reform and those generated by the existing curriculum, the analysis could be more balanced for a different reading of Catherine, the biology teacher’s practices to implement curriculum reform. In this venue, the concept of cultural (re)production set a framing for an institutional curriculum reform that should bring together both societal organizations and educational practices; it is a useful concept for an alternative reading. The reform is conveyed by the actions and operations deployed by Catherine, her position in this field is assumed almost equal to that of Barma’s position, and the reform, as a public policy, should be also part of this structural relation between agents. In fact, everyone is working with a school that has a “long established tradition (150 years) of intellectual freedom and responsible education for young girls” and this adds to the tensions of how curriculum is implemented.

In this way, Catherine, Barma, the students, the school principal, the laboratory technician, other teachers and health professionals appear, along with public policy proponents and activity theorists, are all similarly active in the construction of this specific reform. They all share the same social space in the field of cultural (re)production. As a cultural artifact, even readers, consultants, commentators of the CSSE journal are part of this field. In these manners I propose that “boundaries that are created and transgressed between multiple activities in practice” are better visualized from Bourdieu’s sociological concept of field, position, and disposition of the agents. From this assumption, what their peers see as a transgression in Catherine’s practices, is welcomed by sociocultural theory advocates. Tension came in different shapes, forms and colors. It appears that curriculum reform is an opportunity to liberate and manifest what was latent. This is because activity theory is simultaneously social and historical, not only biographical.

Using activity theory as a lens for interpretation, Barma recognizes that the individual (Catherine) is not studied per se, yet the individual is studied in terms of interaction with others. From this perspective, the unit of analysis consists in interaction. In other words, the unit of observation is not the individual alone but instead the individual in his or her context. But the real tension signaled above, only allows Sylvie to concentrate in “the way Catherine planned and implemented her biology courses with the aim of changing her teaching practice in the context of curricular reform in Quebec.” So, the interaction is only between Barma, who then documents Catherine’s actions, mediated by their interviews and observations of practice. Thus, the use of activity theory is used as a unit of analysis and as an explanatory principle. Once again they are, in different layers, but related.

In a debate located in the mediated action as a unit of analysis, Daniels (2008) cites the controversy of Vygotsky conduced by Wetrsch against “methodological individualism”, stating that a “focus on mediated action and the cultural tools employed in it makes it possible to live in the middle and to address the sociocultural situatedness of action, power and authority” (p. 58). He also presents to the reader that “[f]rom a sociocultural standpoint, even methods such as interviews risk decontextualizing human action by separating actions from the practice in which they have their origin” (p. 59). With this, I do not express a critic of Barma’s work; rather, what I want to signal is that from a hard sociological perspective, the processes of objectification in the interpretation of data are significant in addressing the context—how it is incorporated, and the situation—how it is involved. In so doing, alternative readings emerge, those that integrate both types of tension, i.e., between the organization and reform and practices. In connecting these, the researcher is involved as mediator but also as part of the situation being mediated.

In my view, the real first tension is generated by and for the compulsory of a vertical reform over the boundaries of real professional trajectories it aims to address. This, by doing a combination of “… the learning of scientific notions with the explication of cultural, political, social and ethical considerations—all as part of documenting the questions and issues laid before students by science teachers”, the tension translates into the new competences in which cultural, political, social and ethical considerations fall in the sphere of teacher’s responsibilities. In this way, the teacher is situated between Scylla and Charybdis, meaning to cope with these new considerations and the learning of scientific content; that is, having to choose between two seeming conflicting decisions—to enact reform or remain in a position that does not meet her professional trajectory. Maybe this is why the teacher involved in this case study revealed a “high level of anxiety” towards getting involved in the planning and implementation of novel teaching/learning activities.

Implementation of reform in a biology classroom: reflection on the process

Once more from a relational perspective Catherine is confronted by a twofold contradiction: to solve tensions generated by the curriculum reform that was not a part of her previous professional practice; and to take on new practices, maybe due to the presence and aims of Barma, that were not generated by her school. In between these contradictions are those addressed by the European and American planning organizations. In such a view, the boundaries of the real tension become a bit more focused. The biology teacher was not a participant in the planning process nor was her opinion taken into consideration regarding the reform. Is this an example of true “democratic and humanistic perspective” in the Quebec Education Program dedicated to the Science and Technology subject area? In addressing this question, we are in the field of socioculturally anchored reform practices. They advocate for such practices, yet do not include teachers themselves in this process.

Maybe Barma’s prime target was the outcome of the awareness campaign of the tanning salon. One could expect the documentation on that object and the evidence of this goal as accomplished. But instead, the unit of analysis for Barma was the reflection of Catherine’s work processes, specifically the content of the interviews (i.e., verbatim d’entretiens, analyse de documents et notes de recherche). And then focusing on the transformation of a group rather than on that of an individual…explain how the participants (individual|collective) allow the biology teacher to transform her practice as she planned and implemented an awareness campaign.

Attention to Catherine leaves to the imagination of the reader that the specific goal oriented action and operation of the students and the community involved outcomes regarding the campaign. In other words, the possibility to appreciate the object and objective effectively was not realized entirely. Although this is not a problem, I think this illustrates one solution that Barma addresses—her role as “as science teacher, curriculum writer and researcher”, and advocate of the reform as well. My problem here is that the group and the collective activity evidence are vanished, or not highlighted in Barma’s paper. However, Barma’s piece clearly shows the experience and challenging process that Catherine undergoes, which we can relate to in her speech, the time and emotional dimensions of her planning and implementing the awareness campaign. Vygotsky calls this perezhivanie. According to Daniels (2008), Vygotsky used this Russian concept in order to emphasize the wholeness of cognitive and emotional elements of the experience. This term integrates the perceptions, emotions, ideals, and imagination that mediate an encounter with the physical or social world. For some time Vygotsky considered it “as the unity of psychological development, integrating external and internal elements in the study of social situation” (p. 43). In this way the context should not be studied as an external circumstance but imbedded or transferred within the individual. Also, perezhivanie denotes the process that gives sense (French: sens) to the behavior experienced and the identity accomplished (Daniels). The deeper level of any significant learning, realization or experience is its meaning posited or tied to a signification. The emotional investment as well as recognition of the cognitive content attached to it can thus become a signification, and part of the individual’s social world. In this way the educational institution are significations embodied (Straume 2011) in the same way that cultural fields produce new significations and replicate the existing ones. From this, it is advisable not to mistake means with meanings or mediations.

As has been pointed out “at a very general level of description, activity theorists seek to analyse the development of consciousness within practical social activity…the psychological impacts of activity and the social conditions and systems are produced in and through such activity” (Daniels 2008, p. 115). And so is the case for the biology teacher in the study. In the evidence reported, the log of learning situation shows her intention or goal directed actions that incorporate the new cultural, political, social and ethical considerations of the curriculum reform. But the text goes far beyond the documentation of a successful experience. In Barma’s words “l’activite′ exerce′e par un individu est e′troitement relie′e a` un but conscient, une motivation lie′e au contexte effectif dans lequel l’activite′ a lieu”. The reconstruction of the trajectory of the biology teacher gives a glimpse of her conscious goal, which is linked prior to her position as a 5-year teacher in her school. If we connect the dots of her previous figure skating teachings, being with young people, and her willingness to innovate beyond the formal rules, her general predisposition toward health issues, in this case the tanning salons, the conscious processes clearly appears. We could also see her disposition at the time of first introduction to curriculum reform, illustrated by her previous “[need] of refusing to fall into a routine”, as a student. And this is seen again after her “[p]redominant concern… to develop students’ autonomy and get them to discover concepts on their own” as a teacher. These statements draw the analogous or at least some continuity to Catherine’s historical disposition as a student and as teacher to take up reform. In many ways, they are not alienated from 150 years of school tradition that aims for intellectual freedom and responsible education for young girls. But in all, this is considered as she also takes position to work with the researcher, who indeed plays a central role in helping to bring the awareness campaign to fruition.

I consider this relationship also as part of the effective and affective (perezhivanie) experiencing of context. The distance proposed by Catherine to the intervention of Barma could be “read” in her conscious arguments regarding two dimensions; the first being time: student’s weekly schedule, time constraints, insufficient training, and pressures related to the summative evaluation; and the second being, emotions: master the current reform, constraints of the school community, teacher’s feelings towards the reform, failure to grasp guidelines behind the school reform, and four or five deserter teachers. Maybe the reform implementation is linked to Barma’s presence as an agent, and this role particularly propels Catherine forward. All of this social and cognitive-emotional localizations allows me to recognize the sequence of the actions, some conscious some others not, that took place. Either way, they are located in the processes of a changing field in which Barma documents the concordance between internal and external changes, directly determined by the curriculum modification and curriculum implementation.

Finally, I make an additional glimpse into the “synchronic oppositions between antagonistic positions… (Consecrated/novice), largely independent of external changes which may seem to determine them because they accompany them chronologically” (Bourdieu 1993, p. 57). Concluding, I must acknowledge the different position Catherine and Sylvie have in this field in order to locate them in Sylvie’s text. As a primal tension, this brings the “real” unit of analysis to focus. So, no act of consciousness is deprived from conditions in the structure neither from the presence of other agents, due to the Latin origins of the word: knowledge something (scere) with others (cum). I am not trying to “[carve] up phenomena into isolated disciplinary slices” either individualistic nor social reductionism (Wetsch 1998, quoted in Daniels 2008, p. 58), but only to propose a bit of Bourdieu’s sociology in what social in sociocultural theory could also mean. Here again, we are in the field of socioculturally anchored reform practices.

The pursuit of an objective that is anchored activity theory

This final point of reflection is initiated by a critique made by Holtzman, who “opens a very general question concerning the kind of theory that is activity theory and suggest that no unified perspective exist on the matter” (Holtzman 2006, quote in Daniels 2008, p. 116). I recall this critique particularly because it respects the unit of analysis that Barma follows in her study.

Barma describes her version of the activity theory and claims that an object was a “transformation of the environment targeted by the activity: an innovative TLS according to Catherine; the planning and launching of the awareness campaign on the risks of tanning salons.” The question I would like to pose is, what about the outcome of the campaign? Barma offers only a slight view of it.

Perhaps the object was the tanning salon campaign, and the outcome was the creation of the consciousness towards the pros and cons of salon tanning. The narrative style used by Barma, although clear in its account, does not offer the possibility to grasp what really went on; only her opinions and interpretations. But at the end, the object in this paper was the planning chart, neither the campaign nor the consciousness. A simple numerical data of how many students attended tanning salons before and after intervention, or the unheard voices of some students could have illuminated this aspect. Although contradictory, it seems that Barma’s piece has a central problem, that is it, “tends to foreground the individual, or the visible interaction between individuals, at the expense of the structural relations—invisible, or visible only through their effects—between social positions that are both occupied and manipulated by social agents” (Bourdieu 1993, p. 31). The structural relations and their effects are ‘invisible’ and only modestly deployed by the different positions that Barma and Catherine have in the field. The real individuals, the students, and in some way even Catherine, are less foregrounded at the face of a reform.

Considerations for the future

In this essay, I attempt to settle an argument that was curious to me in the beginning. If activity theory is to be considered a promising theoretical lens for research, in Latin America (or elsewhere), the development of a more integrated and interdisciplinary effort has to be made. For scholars to amalgamate the fundamentals of activity theory with other theorists and theories, also grounded in historical and social contexts, we must consider how to better utilize its complexities to understand social phenomena. Activity theory is not a triangle to be filled; it can be a useful framework that needs to be developed and situated in every society—curriculum reform and classrooms—at any given time.

References

Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production. New York: Polity Press.

Daniels, H. (2008). Vygotsky and research. New York: Routledge.

Straume, I. S. (2011). Learning and signification in neoliberal governance. In Depoliticization: The political imaginary of global capitalism. Retrieved April 29, 2011 from http://www.academia.edu/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This review essay addresses issues raised in Sylvie Barma’s paper entitled: A sociocultural reading of reform in science teaching in a secondary biology class (doi:10.1007/s11422-011-9315-9).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

García G., C.M. Science curriculum reform as a socioculturally anchored practice. Cult Stud of Sci Educ 6, 663–670 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-011-9345-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-011-9345-3