Abstract

With the emergence of police legitimacy as a major indicator of good policing, scholars have continued to push our conceptual understanding of this construct. In recent years, a debate has emerged about whether four factors—lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness—are possible sources of legitimacy judgments (Tyler in Annual Review of Psychology 57, 375–400, 2006) or actual components of legitimacy (Tankebe in Criminology 51, 103–135, 2013). My goal in the present paper is review the contours of this debate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the last 20 years, police legitimacy has emerged as a major concern among policing scholars, practitioners, and policy makers. In large part, this has been driven by dozens of studies linking police legitimacy to higher levels of legal compliance (Walters and Bolger 2019) and cooperation (Bolger and Walters 2019) among community members. In the US, this work culminated in the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (2015) designating legitimacy as the “foundational principle underlying the nature of relations between law enforcement agencies and the communities they serve” (p. 1).

At the same time, debate has also been brewing among criminologists about the appropriate way to measure and model legitimacy. Traditionally, scholars have followed Tyler’s approach whereby individuals’ felt obligation to obey the police and support for the institution are used to measure their perceptions of the legitimacy of the system (e.g., Sunshine and Tyler 2003). Studies then examine the possible sources (i.e., potential predictors) of those legitimacy perceptions, such as lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness of police. However, Tankebe (2013) challenged this approach by arguing that those four constructs actually are the components of legitimacy, rather than the possible sources.

The most recent front of this debate has emerged within the pages of this journal. In 2017, Sun and colleagues published a study testing Tyler’s modeling approach in China. Later, in 2018, Sun et al. analyzed the exact same dataset with almost the same set of items to assess the utility of Tankebe’s (2013) conceptualization of legitimacy. A few months later, Jackson and Bradford (2019) published a response to Sun et al. (2018) arguing that their study was methodologically flawed and that this flaw created a conceptual problem. More specifically, they posited that Sun et al. (2018) had taken a normative approach to conceptualizing legitimacy but had claimed to find empirical support for that conceptualization using a statistical technique that was unable to establish such support. In their eyes, Sun et al. (2018) had essentially imposed a normative definition of legitimacy rather than discovered that definition through empirical testing. Cao and Graham (2019) provide a response to Jackson and Bradford’s critique, rejecting many, if not all, of their arguments or claiming they were not applicable in the present debate.

My goal in this paper is to provide a rebuttal to the critique of Cao and Graham (2019). As I will argue, many of their complaints against Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) criticism are based on mischaracterizations of their argument and/or misrepresentations of the legitimacy literature on which they base their arguments. Moreover, Cao and Graham fail to adequately respond to the central methodological critique proffered by Jackson and Bradford. In what follows, I will first provide an overview of the theoretical measurement strategies of both Tyler (2006) and Tankebe (2013) to clarify the contours of the debate and orient uninitiated readers. Second, I will describe Sun et al.’s (2018) contribution to the legitimacy measurement debate and outline Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) critique of that approach on both methodological and conceptual grounds. Finally, I will examine the veracity of Cao and Graham’s criticisms of Jackson and Bradford and highlight how that criticism is lacking.

Two Approaches to Conceptualize and Measure Legitimacy

Tyler (2006) and Tankebe (2013) represent two fundamentally different ways to conceptualize and measure legitimacy. In large part, this emerges from the disciplines they draw from in their theorizing. While Tyler (2006) emphasizes a psychological understanding of legitimacy, Tankebe (2013) draws from political science in making his arguments.

The Psychological Approach

The majority of policing scholarship to date has followed Tyler’s (1990, 2006) lead with respect to the conceptualization and measurement of legitimacy. Tyler (2006) defines legitimacy as a “psychological property of an authority, institution, or social arrangement that leads those connected to it to believe it is appropriate, proper, and just” (p. 375). Typically, scholars within this tradition have measured legitimacy by assessing individuals’ perceived appropriateness of the police (e.g., institutional trust and/or normative alignment) and felt obligation to obey, with the latter reflecting the individuals’ belief that an authority is appropriate and proper and therefore has the right to dictate appropriate behavior (e.g., Jackson et al. 2012; Sunshine and Tyler 2003; Tyler and Jackson 2013).

This approach is rooted in a psychological understanding of group dynamics in hierarchical systems and the internalization of group norms. On this account, individuals are powerfully motivated to join groups as a means to establish their identity and to promote self-worth and self-esteem (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tajfel and Turner 1979; Tyler 2001). As individuals identify with a particular group, they start to merge their self-concept with that of the group by internalizing its goals, values, and motivations. A key part of this internalization process is the recognition of the group’s authority figures as an appropriate means to regulate the behavior of group members (Tyler 1997). In its purest form, this is what legitimacy signifies in a Tylerian sense, that individuals have internalized group norms and values to the extent that they recognize the position of power of group authorities and accept their role as regulators of behavior. Thus, legitimacy reflects a normative alignment between an individual’s values and the group’s values, whereby one accepts the duties and responsibilities attached to group membership (Jackson et al. 2013; Tyler and Trinkner 2018).

As a result of conferring legitimacy onto an authority, individuals feel it is their obligation or duty to follow the authority’s directives and uphold the norms and rules associated with group membership. Importantly, this obligation does not reflect an instrumental motivation on the part of the individual (e.g., obedience due to the fear of punishment), but rather a voluntary deference to authorities that flows from the internalization of group norms and values. In essence, individuals who view an authority as legitimate voluntarily defer to the authority because it is the right thing to do as members of the group. Within this framework, then, legitimacy measures tapping into respondents felt obligation to obey the law arguably serve as substitute measures of legitimacy as obligation emerges as a result of legitimacy.

However, there is some confusion within the Tylerian conceptual approach about whether obligation to obey is a constituent part of legitimacy or whether it occurs downstream and should be considered a distinct construct. In large part, this stems from inconsistencies within the theoretical literature. On one hand, a careful reading of Tyler’s work suggests that obligation is the result of conferring legitimacy on an authority. For example, in his 2006 review, Tyler does not include obligation in his definition of legitimacy, but rather stresses that legitimacy is something that causes a felt obligation to obey (e.g., “[Legitimacy] is important because when it exists…it leads them to feel personally obligated to defer to those authorities, institutions, and social arrangements.” p. 376, emphasis mine). Nor is this type of argumentation limited to that paper: “…legitimacy is based on beliefs that legal authorities have the right to dictate appropriate behavior. As a consequence, members of the public internalize an obligation and responsibility to follow the law and obey the decisions of legal authorities” (Tyler et al. 2014, p. 756, emphasis mine). As a result of the authority’s legitimacy, individuals may feel obligated to obey, and such obligation, in turn, is theoretically linked to subsequent behavior.

Yet, the same careful reading will also find that in other instances, Tyler positions obligation to obey as a constituent part of legitimacy. For example, “I will discuss legitimacy: the feeling of responsibility and obligation to follow the law…” (Tyler 2009, p. 313) or “Legitimacy is a feeling of obligation to obey the law and to defer to the decisions made by legal authorities” (Tyler and Fagan 2008, p. 235). In other cases, he positions evaluations of appropriateness and obligation to obey as (nearly) concurrent constructs: “In particular, when one recognizes the legitimacy of an institution, one believes that the institution has the right to prescribe and enforce appropriate behavior, and that one has a corresponding duty to bring one’s behavior in line with that which is expected” (Tyler and Jackson 2013, p. 87). On this account, an evaluation of appropriateness is so intricately tied to felt obligation the two essentially occur in tandem, even if the appropriateness evaluation technically comes first (see Tyler and Jackson 2014 for a similar argument).

While it is true that these inconsistencies create some confusion about the exact status of obligation to obey within Tyler’s approach to modeling legitimacy, the fact that they exist is a moot point within the present debate. Importantly, nowhere in his writings does Tyler suggest that legitimacy is composed of lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness. Rather these constructs are consistently described as possible sources—that is, potential antecedents—of legitimacy, and the extent to which they are fundamental to the legitimation process is a very real and empirical question.

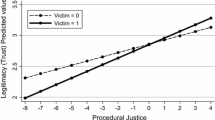

Within Tyler’s approach, a central task of police legitimacy scholars is to assess the factors that promote perceived legitimacy and by extension encourage the felt obligation to obey the police and law. Dozens of studies have shown that one of the primary ways in which the police are legitimated is through the use of fair procedures—i.e., procedural justice (Bolger and Walters 2019; Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler et al. 2015a; Tyler and Jackson 2013; Walters and Bolger 2019). Generally, procedural justice refers to the fairness with which an officer interacts with a community member during an encounter (Tyler and Blader 2003a). According to Lind and Tyler (1988), procedural justice is such a vital part of authority interactions because it communicates to individuals that they are a valued part of the group the authority represents. In other words, it is a signaling device used by authorities to confer group status and membership onto individuals. Messages of social inclusion encourage the internalization of group norms and values. Over time, consistent procedurally fair behavior accelerates the internalization of group norms and values and by extension increases the likelihood that individuals will see the authority as a legitimate entity entitled to deference (Tyler and Blader 2003b).

However, procedural justice is “not the only basis upon which authority can be legitimated” (Tyler 2006, p. 384). For example, in situations where individuals do not strongly identify with the social group that an authority represents, they may be more motivated by instrumental concerns rather than relational concerns (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Tyler, 1997; Tyler and Lind 1992). In these instances, the legitimacy of an authority might depend more on the extent to which they fairly allocate resources (i.e., distributive justice) or their effectiveness in regulating behavior among group members. Indeed, research in countries outside the West have found that instrumental concerns (e.g., crime control effectiveness, corruption) are just as strong, if not stronger, predictors of legitimacy than procedural justice (Bradford et al. 2014; Jackson et al. 2014a; Tankebe 2009). Interestingly, in all cases, the authors explain their results, in part, by noting that the police force in that country has historically not represented the native-born population, but rather colonial powers.

The Political Science Approach

In 2013, Justice Tankebe presented a new conceptualization and operationalization of legitimacy that stands in stark contrast to the Tylerian perspective outlined above. Building off the arguments of Bottoms and Tankebe (2012) and rooted in political science (Beetham 1991; Coicaud 2002), Tankebe made two central points. First, he challenged Tyler’s notion that obligation to obey was a constituent part of legitimacy, arguing that scholars should stop using obligation to obey as a measure of legitimacy. Unlike Tyler who sees obligation as a central aspect of legitimacy (despite the inconsistencies noted above), Tankebe refers to obligation as a theoretically “wider concept” than legitimacy in that it could be driven by a variety of non-legitimacy factors.Footnote 1 For example, he noted that in some instances people might indeed feel that they should obey the police for the normatively justified reasons espoused by Tyler. However, he also noted that others may feel they should obey the police for instrumental reasons (i.e., to avoid the costs of non-obedience) or for lack of a viable exit opportunity (i.e., there is no realistic alternative to not obey social authorities).

It should be noted that, at a conceptual level, this is a misrepresentation of Tyler’s perspective. In his framework, one’s obligation to obey does not equal “why one should obey the police and law,” because by definition obligation to obey signifies an internalized value (Tyler 1997, 2006; Tyler and Jackson 2013). People that feel an obligation to obey the police follow the law because they want to (i.e., voluntarily), not because they fear the consequences of non-obedience or because they feel powerless to exit the system. While these latter notions can indeed influence whether or not people obey, they do not denote an “obligation” in a Tylerian sense of voluntary behavior via norm internalization. Instead, they are something else. However, Tankebe’s (2013) critique in this regard does raise an important measurement problem in the use of obligation to obey measures in current scholarship. In most cases, those measures do not adequately distinguish between these different motivational forces. For example, a person might strongly agree with the statement “I should follow police directives, even if I don’t like the way they treat me” for normative obligatory reasons or for instrumental and/or dull compulsion reasons. This is an issue that should be addressed in future work (see Pósch et al. 2018 for a larger discussion and empirical exploration).

Second, Tankebe (2013) questioned how scholars should measure legitimacy given his argument that obligation to obey was not an appropriate measure. To answer this question, he drew from Beetham’s (1991) work on the structure of political legitimacy (see also Bottoms and Tankebe 2012). On this account, “power is legitimate if it meets three conditions: legality, shared values, and consent” (Tankebe 2013, p. 7). Using this framework, Tankebe argued that legitimacy is composed of lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness. Importantly, he claimed, these four constructs are legitimacy, rather than possible sources of legitimacy.

Lawfulness taps into the legality dimension of Beetham’s (1991) typology in that legitimate power, at its most basic level, must be “acquired and exercised in accordance with established rules” (Tankebe 2013, p. 108). Procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness all tap into the shared values dimension in that they represent the “specific normative expectations of policing in a liberal democracy” that constitutes “the bedrock for the maintenance and reproduction of legitimacy” (p. 111).Footnote 2 In other words, citizens of liberal democracies have value-based expectations about how police exercise authority. In particular, they expect the police will treat them in a fair manner, make fair decisions, and provide an effective means of social control.

To test and support his argument, Tankebe (2013) used data from a large face-to-face survey of London residents concerning the Metropolitan Police Service. Utilizing confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), he presented a model whereby lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness were entered as correlated latent constructs (see Fig. 1, p. 119). The statistical model provided a good fit to the data and the specific items all loaded on their respective factors. He interpreted these findings as empirical support for his theoretical argument that legitimacy is composed of lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness. Moreover, he also showed that when these four constructs were combined into a single measure of “legitimacy,” it was significantly associated with higher perceived obligation to obey the law and greater cooperation with the police (independent of its association with obligation) (see Table 1, p. 122).

In 2018, Sun and colleagues expanded on Tankebe’s initial model in their study of policing in China. They argued that China was an ideal context to examine this new model as the nature of the relation between the government and people within China made parts of Tyler’s model debatable.Footnote 3 For example, non-democratic regimes, such as China, are often coercive in nature, which makes voluntary acknowledgement of legitimacy almost impossible. In these instances, individuals might “feel oppressively obligated to obey legal authorities” (p. 276) even if they do not recognize the legitimacy of legal authority. Moreover, given that authoritarian policing is often abusive and behaves in ways that go against normative expectations of procedural justice, the other factors highlighted by Tankebe (i.e., lawfulness, distributive justice, and effectiveness) may be more pivotal to legitimacy than “originally proposed” by Tyler.

Before describing Sun et al.’s (2018) results, I want to note that it is unclear to me why these issues make Tyler’s approach debatable in the Chinese context. First, as already discussed above, from Tyler’s point of view, it is impossible for anyone to feel “oppressively obligated” to obey the law. This is a contradiction in terms, in the sense that obligation represents an internalized value. Indeed, if people are obeying the police because of oppression, coercion, or dull compulsion, then this by Tyler’s definition is not legitimacy. This does not negate Tyler’s model, but rather indicates that in some instances people may obey for non-legitimacy-related reasons, which is not inconsistent with his perspective. Second, Tyler has written on multiple occasions that the use of coercive power undermines the perception that an authority is appropriate and proper—i.e., legitimate (Tyler 2009; Tyler et al. 2015a; Tyler and Trinkner 2018). Third, Tyler has never argued that lawfulness, distributive justice, and effectiveness are “less imperative” as a de facto principle. Instead, he has long argued that the degree to which these different factors shape perceptions of legitimacy is an empirical question, dependent on the specific context under investigation (Tyler 1989). For example, he has placed special emphasis on the degree to which people identify with the social group the authority represents (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler 1989, 1997, 2006; Tyler and Blader 2000; Tyler and Blader 2003b). While it is true that Tyler often singles out procedural justice as one of the most important factors in legitimating the police, this is due to the overwhelming amount of research showing that relational concerns are usually more important in predicting outcomes than instrumental concerns (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler and Lind 1992; Tyler and Jackson 2013).

Moreover, given Sun et al.’s (2018) description of the Chinese regime, Tyler’s model would expect instrumental forces like effectiveness and distributive justice to carry more weight in terms of explaining the public’s legal perceptions. As Sun et al. (2018) note, China often violates basic norms of procedural justice given their authoritarian nature. From a Tylerian perspective, then, the Chinese government is routinely sending signals to the populace that they are not a valued part of the social group the police represent (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler and Lind 1992). Such messages of exclusion increase the likelihood that Chinese citizens will be more oriented toward that legal authority along instrumental concerns (Tyler 1997). Indeed, this is precisely what Sun et al. (2017) found in an earlier study examining Tyler’s model within a Chinese context. In that analysis of the data, they showed that police effectiveness was the strongest predictor of police legitimacy.

Setting the mischaracterization of Tyler’s perspective aside, Sun et al. (2018) followed a similar modeling strategy as Tankebe (2013). First, they estimated a CFA model in which lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness were entered as latent variables. However, unlike Tankebe, they also included a second-order latent variable labeled as “legitimacy” (Fig. 2, p. 286). Their model fit the data well and showed strong factor loadings. Second, they ran a structural equation model (SEM) examining the relationship between “legitimacy” and police cooperation with obligation to obey positioned as a mediator (Fig. 3, p. 287). Their results showed that “legitimacy” was positively associated with both obligation and cooperation and that obligation was positively associated with cooperation. Follow-up tests suggested that obligation partially mediated the relation between “legitimacy” and cooperation. Sun et al. (2018, p. 288) argued their results showed substantial empirical support for the alternative conceptualization of legitimacy: “In short, Tankebe’s argument that procedural justice variables should be considered as indicators, rather than antecedents, of legitimacy, is supported.”

Pushing Back

In 2019, Jackson and Bradford published a critique of the modeling strategy used by Sun et al. (2018) and Tankebe (2013). Their argument consists of two prongs, one methodological and the other a conceptual problem that stems from the methodological error at the heart of that strategy.

The Methodological Critique

At the outset of their response, Jackson and Bradford (2019) note that both Sun et al. (2018) and Tankebe (2013) base their central theoretical argument—that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are legitimacy rather than possible sources of legitimacy—on an empirical claim: namely, that the findings from their CFAs show that the aforementioned factors must be constituent components of legitimacy rather than possible sources of legitimacy. However, Jackson and Bradford argue that CFA is not a sufficient analytical tool to adjudicate between which conceptualization is most appropriate. In other words, CFA cannot say one way or the other if scholars should think of lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness as antecedents of legitimacy (Tyler’s argument) or components of legitimacy (Tankebe’s argument).

Why would this be the case? Structural equation modeling (of which CFA is one version) models the underlying covariance matrix among observed variables within a set of constraints that are specified by the researcher (Allison 2018). Importantly, SEM in-of-itself does not provide meaning to those covariances or offer any guidance to how those covariances should initially be structured. Rather, it is the job of the researcher to provide both meaning and structure, which is usually done through a careful analysis of prior theoretical work that provides a blueprint of how to structure and interpret the relationships among the observed variables. For example, Sun et al. (2018) structured the relationships among their observed variables following Tankebe’s (2013) conceptual approach, namely that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are constituent components of “legitimacy,” which they structured as a second-order latent variable explaining the correlations among the four components. Finding that this model fit the data well, they concluded that these results support Tankebe’s (2013) conception of legitimacy over Tyler’s (2006) conception. In short, it was the theory they used to structure the correlations among their data that gave meaning to the statistical numbers of the output, rather than the output itself.

However, as Jackson and Bradford (2019) argue, they could have just as easily used a different conceptual model to impose the same structural constraints on the same set of data and get the same results yet come to a wildly different interpretation. For example, Tyler has noted that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are possible sources of legitimacy perceptions (Tyler and Jackson 2013; Tyler and Lind 1992; Tyler 2006). Imagine a scenario where Sun and colleagues decided to call their second-order latent variable “sources of legitimacy” rather than “legitimacy.” Given that they would have structured their covariances in the same exact manner using the same exact observed variables, they would have received the same exact results. Following the logic used in the original analysis, the results would support the notion that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are best conceptualized as sources of legitimacy rather than constituent components of legitimacy (given that the results showed good scaling properties like model fit and high factor loadings).

How can it be the case that the same exact results can be interpreted in such contradictory ways? The answer is that the theory/conceptualization one uses to structure the covariances among observed variables is what provides meaning to SEM results; the results by themselves do not. This becomes a problem when two competing conceptualizations utilize the same observed variables and impose the same set of structural relationships among observed variables, as is the case here. In these instances, CFA (or SEM more generally) will be unable to support one conceptual stance over the other because both theories are modeling the same covariances. They are just labeling those covariances in a different manner, thus, creating a different meaning (of the same exact results). The fact that Sun et al.’s (2018) modeling strategy fit the data well does not and cannot indicate that their approach is a better conceptual approach than Tyler’s (2006).

To further make this point, let us follow Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) argument to its logical conclusion. The same methodological issue that makes Sun et al.’s (2018) interpretation of their CFA results suspect, also apply to the SEM model they present assessing the relations among “legitimacy,” obligation to obey, and police cooperation. Whereas Sun et al. (2018) in their paper positioned obligation to obey as a distinct construct from their “legitimacy” latent variable, from a Tylerian perspective, one could just as easily label obligation to obey the law as “legitimacy” (as done in dozens of prior studies, including the 2017 study by Sun and colleagues which used the same data as the 2018 paper) and continue to label lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness as possible sources of legitimacy (see Jackson and Kuha 2016).

Importantly, this conceptual stance would still structure the covariances among the observed variables in the same manner, leading to the same exact output. However, in this scenario, we would make a fundamentally different interpretation given our use of a different conceptual model. Here, the sources of legitimacy (i.e., lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness) predict the perceived legitimacy of the police (i.e., obligation to obey) which in turn predicts public cooperation toward the police. Moreover, the results show that legitimacy is not only empirically distinct from the sources of legitimacy, but also acts as a mediator between those sources and public cooperation. Once again, we see that if Tyler’s conceptualization was used to interpret the results rather than Tankebe’s approach, then the conclusion would be that the results show support for Tyler (as opposed to Tankebe). But at the end of the day, we are still talking about the same exact results. Thus, in reality, using CFA (or SEM) in this instance takes us no closer to understanding which of the two approaches is the more appropriate way to conceptualize legitimacy.

As a second illustration of Jackson and Bradford’s methodological critique, let us review the results in the original Tankebe (2013) article. Recall that Tankebe also conducted a CFA, but he did not include a second-order latent variable accounting for the correlations among effectiveness, procedural fairness, distributive justice, and lawfulness. Instead, he allowed those latent variables to correlate with each other directly. He interpreted the results from his CFA as evidence of the veracity of his theoretical conceptualization of legitimacy over Tyler’s (2006). However, again, CFA cannot provide such empirical support to his conceptualization. If the theoretical veneer is stripped from the results, all they show is that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are all correlated with each other to varying degrees and are measured well (Fig. 1, p. 119). In this respect, it is clear they do not contradict Tyler’s approach, as he has never argued that these four constructs would not be correlated with each other or difficult to measure. Furthermore, one could just as easily interpret these results as support for the notion that these four constructs are actually sources of legitimacy rather than constituent parts (assuming one started from a Tylerian conception).

In addition to his CFA, Tankebe also ran a series of models in which (1) obligation to obey was regressed onto lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness and (2) police cooperation was regressed onto all five of those variables. Again, he concludes that his results support the argument that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are constituent parts of legitimacy, rather than sources. But again, if the results are not interpreted through this theoretical lens, one will come to a very different conclusion. For example, in his first model, he shows that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are all positively associated with obligation to obey (model 2). Obligation, in turn, is positively associated with cooperation to obey the police, as are lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness (model 4). This general pattern of results has literally emerged across dozens, if not hundreds, of studies over the last three decades (e.g., Bolger and Walters 2019; Tyler and Fagan 2008; Tyler and Jackson 2013, 2014). However, in those cases, the results were not viewed as support for the notion that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness were components of legitimacy. Instead, they were interpreted as support for Tyler’s contention that those variables are sources of legitimacy, which in turn encouraged citizens to cooperate with the police.

As a third illustration of this point, Jackson and Bradford (2019) test the same CFA model as Tankebe (2013) across 30 different countries. In large part, they find the same well-fitting model across all of them. Again, using the argument laid out above, their results do not support either Tankebe’s conceptualization or Tyler’s conceptualization. Instead, their results simply show that effectiveness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and lawfulness are correlated with each other to varying degrees and are measured well. How one interprets what the correlations among these constructs means depends on the conceptual stance one takes. Importantly however, and central to Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) primary critique, the veracity of that interpretation must come from one’s conceptual analysis and theoretical argumentation, not from the results produced by the analytical technique.

The Conceptual Critique

The second prong of Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) critique is a conceptual problem that emerges from the methodological issue discussed above. Again, the argument is that CFA cannot say one way or the other which approach to conceptualizing and operationalizing legitimacy is correct. Given this, one must conclude that the findings by Sun et al. (2018) and Tankebe (2013) do not in-and-of-themselves support their argument that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are constituent components of legitimacy. However, by the same token, this means that their results also do not refute their argument either. At the end of the day, it is the conceptual stance one takes a priori that provides meaning to the results, rather than the results themselves.

One could ostensibly accept this critique and simply decide to use Tankebe’s (2013) approach because s/he could be more inclined toward that model (the potential reasons for that inclination are not pertinent to the discussion at hand). Indeed, Jackson and Bradford (2019) explicitly note that “Legitimacy is an abstract and unobservable psychological construct, and there are numerous ways to operationalize the perceived right to power, aside from the standard ways of institutional trust and/or normative alignment and/or obligation to obey” (p. 22). At the same time, they strongly caution against using the methodological approach espoused by Tankebe (2013) and Sun et al. (2018) because CFA does not provide the all-important evidence that is being claimed.

To elucidate their concerns, they take advantage of a conceptual distinction used among political philosophers that is fundamental to understanding the nature of legitimacy: normative legitimacy vs. empirical legitimacy (Jackson et al. 2018). Normative legitimacy, in this instance, is a value-laden term that proscribes a certain set of objective criteria police officers would need to meet in order for an outside observer to determine that they are legitimate authorities—i.e., that they have a right to rule or that their position as a source of social control within society is appropriate and proper.Footnote 4 Empirical legitimacy, on the other hand, refers to the degree to which individuals actually believe that police officers are in fact legitimate, based on whatever culturally and personally contingent criteria that they use to judge rightfulness. In this sense, the level of legitimacy and the value-content of legitimation are wholly determined by people’s own subjective experience, regardless of any normative or objective criteria that might be imposed from an outside observer.

Traditional scholarship on police legitimacy, such as Tyler (2006), falls within the confines of empirical legitimacy. Rather than dictate what objective criteria determines the legitimacy of police authority, it is left open to empirical inquiry to discover whether individuals believe the police have the right to their power and recognize their authority to govern. Central to this pursuit is the identification of those factors used by individuals to make those judgments. Scholarship rooted in the empirical legitimacy approach thus draws a sharp contrast between judgments of legitimacy and the actual process of legitimation. As a result, it takes as a given that different individuals and different groups will vary in the degree to which they judge an authority as legitimate, will vary in terms of what specific factors inform that judgment, and that the interplay between legitimacy and legitimation will almost certainly vary from context to context. For example, in one culture, individuals may base their judgments about the degree to which the police are an appropriate authority on the degree to which the police are able to control crime (e.g., Bradford et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2017). However, an individual in a different culture or context may base her legitimacy judgment on the degree to which that officer follows the law (e.g., Jackson et al. 2014a). Still, another individual from another culture may base his decision on the degree to which officers behave in a fair manner when interacting with community members (Tyler et al. 2015b; Murphy et al. 2016). Ultimately, this is the goal of scholarship investigating empirical legitimacy: to determine the factors that shape people’s perception that an authority has a right to their power and are entitled to obedience.

However, the alternative conceptualization used by Tankebe (2013) and Sun et al. (2018) falls more squarely within the normative approach. Why might this be the case? Because they are effectively determining, as outside observers, the criteria that designates whether an authority is or is not a legitimate authority figure. On their account, the police are legitimate to the extent that the public believes the police (1) follow the law and rules regulating the means by which they can obtain and exert their power, (2) treat people in a fair manner, (3) make decisions that are equitable and fair, and (4) are effective in controlling illegal behavior. Within this framework, there is no distinction between legitimacy itself and the process by which an entity becomes legitimated. Rather the constructs that are typically used to explore the legitimation process (i.e., lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness) are positioned as legitimacy.

Jackson and Bradford (2019) explicitly state that they do not have a problem with scholars taking such a normative approach to the study of legitimacy. As they note, “Researchers are, of course, free to impose onto a given context the criteria that people use to judge the legitimacy of police” (p. 3). In their eyes, it is possible that a scholar could examine a particular situation, context, or authority and make a normative case (in the political sense) that a certain set of criteria are so fundamentally important to what it means to be considered an appropriate and proper—i.e., legitimate—authority that any empirical conceptualization of legitimacy must in fact include those criteria as constituent components of legitimacy itself. However, in these instances, the scholar needs to be clear that they are establishing value-laden normative criteria and provide justification that these criteria are fundamental pillars of legitimacy within that particular context through context-specific conceptual analysis and operational argumentation.

However, as Jackson and Bradford (2019) argue, this is not the process that Tankebe (2013) and Sun et al. (2018) followed. Instead, they conducted CFAs and interpreted the results of those tests as empirical support for their predetermined normative criteria. However, as explained by Jackson and Bradford (and reiterated in my discussion above), CFAs are unable to provide empirical support in this manner. Rather than providing empirical support for the notion that legitimacy is composed of lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness, their analysis only showed that these were positively correlated constructs with good scaling properties. Effectively, therefore, they imposed a normative set of criteria onto the meaning of legitimacy within the Chinese context under the guise of a “smokescreen of (non-existent) empirical evidence” (Jackson and Bradford 2019, p. 3). Put another way, their approach blurred the important distinction between empirical and normative legitimacy, claiming it exemplified the former while in reality conforming to the latter.

One may wonder what the harm is in blurring the distinction between normative and empirical legitimacy. While one may concede Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) critique at a conceptual level, what practical impact does it have on understanding police legitimacy? After all, both Tankebe’s (2013) and Tyler’s (2006) approach emphasize procedural justice, for instance, so in practical terms both would argue that the police need to be cognizant of treating people in a fair manner. To answer this question, Jackson and Bradford (2019) highlight that one of the reasons why Sun et al. (2018) explicitly adopted Tankebe’s strategy is that it offers a high level of cultural sensitivity in the discussion of legitimacy. On Sun et al.’s (2018) account, this superior cultural sensitivity comes from Tankebe (2013) basing his conceptual argument within the dialogic approach to legitimacy championed by Bottoms and Tankebe (2012) which stresses that legitimacy emerges from negotiated engagement in which power holders make claims on the right to govern and non-power holders either accept or reject those claims. In this respect, Tankebe (2013) recognizes the “dynamic nature embedded in police–citizen encounters, arguing that the different dimensions of legitimacy tend to have different effects across societies and among social groups within the same society” (Sun et al. 2018, p. 279).

Implicit in this argument is that since Tankebe (2013) positioned legitimacy as composed of four factors that may be disproportionately more/less important components of legitimacy, his approach offers a more varied explanation of legitimacy in disparate cultural contexts than Tyler’s (2006) model which ostensibly is largely restricted to procedural justice. However, this is a mischaracterization of Tyler. First, Bottoms and Tankebe’s (2012) dialogic approach is not incompatible with Tyler’s approach to conceptualizing legitimacy. The dialogic approach only maintains that legitimation should be viewed as a bidirectional process in which both police officers (i.e., power holders) and community members (i.e., non-power holders) provide unique contributions to whether or not the police are viewed as a legitimate authority by community members. It does not presuppose a particular conceptualization of legitimacy. In this respect, one could study police legitimacy within a dialogic framework using either Tankebe’s or Tyler’s conception of legitimacy. Second, as I have already noted above, Tyler’s model does not argue that procedural justice is the only or most important predictor of legitimacy as a de facto principle, but rather that different factors will be differentially important depending on the relationship between the police and citizens in a given context (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler and Lind 1992; Tyler 1997).

These mischaracterizations notwithstanding, Jackson and Bradford (2019) maintain that Tankebe’s approach actually “lacks cultural sensitivity because it is the outside experts…who are imposing the criteria that people use to judge institutional legitimacy” (p. 3). In essence, this strategy is imposing a particular value-laden meaning onto legitimacy given that CFAs cannot empirically establish the validity of the component model and, as a result, embody a normative conceptualization of legitimacy (as explained previously). In reality, rather than leaving it an open empirical question as to what factors in a given cultural context encourage the population to view the police as appropriate authorities who have the right to govern, this strategy a priori determines that police officers are legitimate if they are lawful, procedurally and distributively just, and effective.

If such an approach were limited to an isolated set of studies, the ramifications of its usage would similarly be isolated. However, Jackson and Bradford (2019) contemplate the consequences of large-scale adoption by examining Tankebe’s (2013) model across 30 countries featuring a diverse set of social, legal, and political contexts. They found similar well-fitting models with good scaling properties across all countries. As discussed above, this in-and-of-itself does not indicate that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness should now be considered components of legitimacy rather than possible sources of legitimacy. However, imagine if scholars were unaware of the problems of using CFA in this instance and instead concluded that the results empirically support Tankebe’s model (similar to Cao and Graham’s (2019) conclusion discussed below). Moreover, given the widespread support across 30 countries, scholars begin to define legitimacy as lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness in their future research. Rather than this work being culturally sensitive, they would instead be inadvertently imposing an essentially universal system of normative criteria onto disparate cultures and contexts that likely have substantial variation in the relationship between citizens and the state that inform the degree to which they judge state actors as legitimate authorities. “In practice, therefore, far from being sensitive to cultural variation in the composition of legitimacy…[this approach] flattens out the possibility of variation” (Jackson and Bradford 2019, p. 21).

This potential flattening of variation in the meaning of legitimacy has two important consequences for police legitimacy scholars according to Jackson and Bradford (2019). First, should the Tankebe (2013) approach become widely adopted, it leaves little possibility of assessing which of the four factors are the most important components of legitimacy. If one were to follow this approach, then lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are equally important because they are legitimacy. In other words, if one chooses these normative criteria to define the components of legitimacy, then by definition there is no empirical question about which is the most important component. This stands in stark contrast to prior work exploring empirical legitimacy that has shown important contextual variations linking these factors to an overarching sense that the police are an appropriate authority that has the right to govern. For example, multiple studies show that distributive justice and other instrumental concerns tend to be equally or more important in the legitimation process than procedural justice in countries where the police have historically represented a different social group than the public (Tankebe 2009; Bradford et al. 2014; Jackson et al. 2014a, b).

This issue would not only emerge among examinations across cultures but could occur within the same culture as well. Take for instance, Klockars (1980) classic discussion of the “Dirty Harry” problem. As he explains, the public will often legitimize the police in instances where officers actually violate the law (e.g., due process) if they believe the police are doing so to achieve moral ends (e.g., catching a serial killer). On the other hand, scholars have shown that the very act of stop-and-frisk can undermine legitimacy (Tyler et al. 2014), even though the practice is legal in the US. In the first instance, officers violating the law legitimizes their authority, while in the second instance following the law is delegitimizing. However, none of these contextual variations in the legitimation process would be identified if a researcher used the strategy of Tankebe (2013) and Sun et al. (2018). Perhaps more importantly, if a policy maker is under the assumption that following the law is a core component of police legitimacy, then she will be quite surprised to learn that in both instances her officers following the law actually delegitimizes their authority in the eyes of the public.

A second way in which contextual variation would be flattened amid widespread adoption of the approach by Tankebe (2013) is that it leaves little room to identify other important constructs that shape individual’s legitimacy judgments. As Jackson and Bradford (2019) argue, there are likely other factors that shape individuals’ recognition of the legitimacy of the police beyond lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness. For example, recent research has indicated that community members may base their judgments of police legitimacy on the degree to which they recognize the right of the police to regulate a particular behavior in the first place (Huq et al. 2017; Trinkner et al. 2018; Trinkner and Tyler 2016). The argument here is that citizens will reject the police as legitimate authorities when they feel they are encroaching on their own private domains of autonomous behavior, independent of whether the police do this in a lawful, fair, or effective manner. Again, if a policy maker is working under the Tankebe framework, she may be confused as to why some community members are pushing back against her policies even as she strives to make sure those policies are being implemented in a lawful, fair, and effective manner. To be fair, one could argue that in this scenario, a scholar could just add a fifth component to their legitimacy CFA and see if it improves model fit, but again, that would suffer from the same methodological problem outlined earlier.

Assessing the Response to the Pushback

Now that I have clarified the contours of the debate between Tankebe’s (2013) and Tyler’s (2006) approach to the conceptualization of legitimacy and reviewed Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) critique of the former, it is time to turn attention to Cao and Graham’s (2019) response to Jackson and Bradford. I will begin my response to Cao and Graham on the CFA issue, given that the entirety of Jackson and Bradford’s criticism is built on the (mis)use of this tool to provide empirical support for Tankebe’s conceptualization.

However, one issue must be addressed beforehand. When I was invited to respond to Cao and Graham (in press), I was assured that the manuscript I was given was to be published “as is.” After my manuscript was accepted for publication, Cao and Graham’s piece was published online. In numerous places their published article differed from the manuscript that I was given for the purpose of writing my response. I was not given an opportunity to rewrite my response as this would have held up the publication of the special issue. As such, discrepancies between the quotes provided below and those within Cao and Graham’s published article can be attributed to this process.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis as an Adjudication Tool

At the outset of their response, Cao and Graham (2019) appear to concede Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) central argument that CFA cannot adjudicate between whether lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are best thought of as components of legitimacy (Tankebe’s approach) or sources of legitimacy (Tyler’s approach). As they state, “Rightfully, one of the criticisms [of Jackson and Bradford] is that the confirmative factor analysis modeling is not a good adjudication tool to differentiate possible sources of legitimacy and constituent components of legitimacy” (emphasis mine).Footnote 5 Later on, they make their concession more explicit, “In fact, we agree that CFA modeling is not a good adjudication tool to differentiate possible sources of legitimacy and constituent components of legitimacy.”

However, they then go on to state that, although the point is valid and relevant, it is not applicable because in their eyes Sun et al. (2018) did not:

base their choice of the measurement solely on CFA [but rather] were inspired by theoretical insight of Bottoms and Tankebe (2013) [sic], and they followed Tankebe’s groundbreaking lead (2013) in their research. Therefore, the question is NOT whether CFA can or cannot adjudicate an operational decision, but whether CFA can or cannot assist a researcher in reaching a decision. The answer is an affirmative one. (Cao and Graham 2019)

Having ostensibly laid aside Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) criticism, they go on to argue that Jackson and Bradford’s 30-country test of the model actually shows that Tankebe’s approach is the correct one: “Unwittingly, Jackson and Bradford (2019) have done a service to the field of criminology by providing external validity for the legitimacy measure advanced by Sun et al. (2018) and Tankebe (2013).” In other words, they believe that the 30 CFAs from Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) study show empirical support for the notion that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness should be thought of as components of legitimacy rather than possible sources.

The primary problem with Cao and Graham’s (2019) response is that Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) methodological argument against Sun et al. (2018) and Tankebe (2013) was not about these authors’ choice of measurement, nor was it about what those choices were based upon. Indeed, Jackson and Bradford (2019) note that researchers are free to choose whatever measurement strategy they so desire. The issue for Jackson and Bradford (2019) was how the CFAs were interpreted. Both Tankebe (2013) and Sun et al. (2018) explicitly state in their studies that the CFAs provide empirical support for their contention that lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness are best thought of as components of legitimacy rather than sources of legitimacy. However, as explained above (and by Jackson and Bradford themselves), CFA cannot say one way or the other if these four constructs should be thought of as sources or components of legitimacy. At the end of the day, the argument here is about what latent variable modeling can and cannot do. The fact that Sun et al. (2018) were inspired by theoretical insight or followed prior research has no bearing on this issue and is irrelevant to the discussion at hand. Despite Cao and Graham’s (2019) affirmations, this statistical technique cannot answer the fundamental question at the heart of this particular measurement debate. As a consequence, Jackson and Bradford did not, unwittingly or otherwise, provide external validity to the measure used by Tankebe (2013) or Sun et al. (2018).

One more point is worth addressing before moving on. Cao and Graham (2019) dispute Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) argument that the strategy employed by Tankebe (2013) and Sun et al. (2018) leaves little room to determine which of the four constructs is the most important component of legitimacy. From their perspective:

This is a strange statement and, in the footnote one on page 20, they regurgitate a similar point. Sun et al. (2018) could clearly assess which component of their legitimacy was most relevant within their models. Indeed, Sun et al. (2018, p. 288) revealed that “With the largest absolute value of the factor coefficient, lawfulness stands out as the most important variable in calculating the component of legitimacy, followed by distributive justice, procedural justice and finally effectiveness. (Cao and Graham 2019)

Abdominal movements aside, there are two issues with this reasoning. First, such a strategy would not be applicable within Tankebe’s (2013) study. Recall that he did not use a second-order latent variable, but rather directly correlated the four latent constructs. In this instance, the size of the correlations among lawfulness, procedural justice, distributive justice, and effectiveness tell us nothing about which is the “most important” component of legitimacy. Second, although Sun et al. (2018) manage to sidestep this issue with the inclusion of the second-order latent variable, they introduce a modeling assumption that “legitimacy” has to be unidimensional. However, there is no such established requirement within the police legitimacy literature, nor did Sun et al. (2018) provide an argument for one. Indeed, the disparities between the modeling strategies employed by Tankebe (2013) and Sun et al. (2018) when both came to the same conclusion highlight that such an assumption is not required. Thus, the strategy espoused by Cao and Graham (2019) to assess the most important component of legitimacy is based on a questionable modeling assumption. One could have just as easily modeled the four components without the second-order variable (as Tankebe (2013) did) or even perhaps with two second-order latent variables (e.g., shared beliefs and legal validity, see Beetham 1991; normative justifiability of power and recognition of rightful authority, see Jackson and Bradford 2019). Given these alternatives, the factor loadings from those models (or comparing the factor loadings between the different models) would provide little information about what is the most important component of legitimacy within this approach.

Definitions of Legitimacy

A second major critique leveled at Jackson and Bradford (2019) by Cao and Graham (2019) concerns the “definition” of legitimacy utilized by Jackson and Bradford, in particular their use of the conceptual distinction between normative and empirical legitimacy.Footnote 6 Cao and Graham begin this portion of their critique by recognizing (correctly, I should add) that legitimacy is a complicated, contested, elusive, and multifaceted concept whose full breadth is beyond the scope of their response. Given this complexity, they constrain their discussion to the definition of legitimacy within the context of policing specifically. They note that:

Additionally, they argue that all of these terms can be subsumed by Bottoms and Tankebe’s (2012) concept of audience legitimacy because (quoting Bottoms and Tankebe) audience legitimacy “covers most of the ground in answering Tyler et al.’s important question about what factors create and sustain audience legitimacy.” Building off this discussion, they conclude:

Apparently, Jackson and Bradford’s introduction of political philosophers’ normative legitimacy has outgrown the original definition of Tyler’s legitimacy. Legitimacy in criminological research, we argue, is first of all, audience legitimacy, not political philosophers’ legitimacy. (Cao and Graham 2019).

Before responding to Cao and Graham’s (2019) critique, it might be helpful to refresh readers’ memory about the distinction between normative legitimacy and empirical legitimacy that plays a central role in Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) criticism. An authority is considered legitimate in a normative sense when that authority meets a set of criteria that is predetermined by an outside observer (Jackson et al. 2018), e.g., there are objective indicators that they exercise their power in ways that are lawful, procedurally fair, distributively fair, and effective, or there is public opinion evidence that citizens believe that the police exercise their power in these four ways. However, conceptualizing legitimacy in an empirical sense does not impose any specific set of criteria; empirical legitimacy does not say that for the police to be legitimate they need to act in ways that are lawful, procedurally fair, distributively fair, and effective. Rather, it means examining the degree to which people actually approve of that authority figure—i.e., judge them as legitimate—and finding out the factors that legitimate that authority figure in the eyes of the people. For example, it is an empirical question whether procedural justice is a more important source of legitimacy than lawfulness, distributive justice, and/or effectiveness.

Cao and Graham’s (2019) argument that Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) use of normative legitimacy has apparently “outgrown” Tyler’s original definition of legitimacy bears little resemblance to Jackson and Bradford’s actual use of the concept. Jackson and Bradford introduced the distinction between normative and empirical legitimacy as a way to elucidate the fundamental problem with Tankebe’s (2013) and Sun et al.’s (2018) approach, i.e., it effectively takes a normative approach to conceptualizing legitimacy but presents it as empirical discovery. Nowhere in their article do they discuss that normative legitimacy has or should supplant Tyler’s definition. This is because Tyler has used an empirical legitimacy approach throughout the decades of his work. To put it another way, it is not possible for normative legitimacy to outgrow Tyler’s definition because Tyler does not define legitimacy along a normative set of criteria. This fact is underscored by Jackson and Bradford when they explicitly cite Tyler’s work in their description of empirical legitimacy. Even Bottoms and Tankebe (2012) have stated that “Tyler et al. follow Zelditch in characterizing authority as legitimate when people ‘believe that the decisions made and rules enacted by that authority or institution are in some way ‘right’ or ‘proper’ and ought to be followed’” (p. 124). Notice that statement does not include any normative criteria that define what “right” or “proper” means, rather that is left open as an empirical question. Indeed, this is precisely why, as Cao and Graham note, that “popular legitimacy” has been relabeled as “empirical legitimacy” which is indistinguishable from “subjective legitimacy.” In all three cases, the scholars using those particular terms are not defining legitimacy in terms of a specific set of normative criteria.

It appears that Cao and Graham (2019) are rejecting the use of the distinction between normative legitimacy and empirical legitimacy because they believe that criminological research is first and foremost “audience legitimacy” and not “political philosophers’ legitimacy.” Again, the political philosophers’ legitimacy they are referring to is simply a way to distinguish between two different ways to think about legitimacy. The fact that it comes from political philosophy does not mean that it cannot (or should not) be used in criminology to help our understanding of this complicated, contested, elusive, and multifaceted concept. Both approaches have their place. For example, one could compare the picture that emerges from Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) 30-country dataset on public opinion regarding police legitimacy with national-level indicators of the normative legitimacy of the police in each country based on rule of law indicators for instance. However, one cannot essentially utilize a normative conceptualization of legitimacy and then argue that they found empirical support for that particular conceptualization over another conceptualization based on statistical techniques that cannot provide such support.

Regardless of whether one believes criminologists should or should not draw from political philosophy to improve their thinking on a topic, Cao and Graham’s contention that the empirical–normative distinction is misplaced because “legitimacy in criminological research…is first of all, audience legitimacy” is problematic on its own merits. The reference to audience legitimacy comes from Bottoms and Tankebe’s (2012) statement on the nature of legitimacy. In that paper, they argued that social scientists studying legitimacy have failed to adequately understand the dialogic, bidirectional nature, of legitimacy. On their account, an authority, like a police officer, speaks (i.e., has a dialogue) to a variety of different “audiences” (i.e., various community members/groups) and makes claims about the legitimacy of his or her status, position, and/or power. The degree to which those audiences accept those claims is considered “audience legitimacy” in Bottoms and Tankebe’s parlance. In other words, audience legitimacy is the perception of police legitimacy from the perspective of community members. Any time a researcher is examining police legitimacy from the community members’ perspective then, they are studying audience legitimacy. Importantly, audience legitimacy is not dependent on whether one takes a normative approach or empirical approach in conceptualization. A researcher could use either and they would still be studying audience legitimacy so long as they are doing it from the perspective of the audience. Whether they assess the degree to which the audience believes the police meet a set of predetermined normative criteria or assess if the audience approves of the status, position, and/or power of the police more generally matters little.

Furthermore, their suggestion that legitimacy in criminological research is audience legitimacy is contrary to the state of the literature in criminology today. One of the most important issues raised in Bottoms and Tankebe’s (2012) exposition on the dialogic nature of legitimacy is that there are actually two sides to the legitimacy coin: legitimacy from the perspective of those that do not hold power (i.e., the audience) and legitimacy from those that do hold power (e.g., police officers). While criminologists have largely focused on the former, they highlighted an “urgent need to develop studies of power-holder legitimacy” (p. 160) which they labeled self-legitimacy. Since their call, there has been a growing amount of research on this topic, much of it done by Tankebe himself (Bradford and Quinton 2014; Meško et al. 2017; Nix and Wolfe 2017; Tankebe 2014; Tankebe and Meško 2014; Trinkner et al. 2019). Thus, the sentiment that legitimacy within criminological research is audience legitimacy is simply not true.

Testing Legitimacy Across Cultures

The third major criticism of Jackson and Bradford (2019) by Cao and Graham (2019) concerns the former’s discussion of testing legitimacy across cultures. From their perspective, Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) perspective is too broad and absolute. As they argue:

Jackson and Bradford (2019, p. 4) argue that ‘the content of legitimation (i.e., the bases of which legitimacy is justified or contested) are an empirical question.’ Therefore, it cannot be studied with an a priori definition. Put differently, they argue that police legitimacy is place-specific and culture-specific. (Cao and Graham 2019)

While Cao and Graham (2019) concede that, at least at the phenomenological level, this perspective is not wrong, they contest that Jackson and Bradford (2019) “as social scientists…justify their argument with trendy criminology: cultural sensitivity.” On their account, Jackson and Bradford are wrongly accusing Sun et al. (2018) of imposing a “definition of legitimacy developed in England to the Chinese public” because they:

…advocate that empirical legitimacy must tie to a local culture and when testing legitimacy in a new context, one must not assume any prior concept for the locals. According to their alleged cultural sensitivity approach, legitimacy can only be a bottom-up thing and can only be studied culture by culture because each culture may have different weights on the components of legitimacy.

As a consequence of their trendy criminology extolling alleged cultural sensitivity, Jackson and Bradford (2019) have raised a fundamental question about “how should a researcher conduct an empirical test of a theory” (Cao and Graham 2019).

Cao and Graham (2019) accept the general idea that content or culture will depend on context and that researchers should be aware of this when testing theories across cultures. At the same time though, legitimacy is a general theoretical concept and assessing the applicability of a concept across cultures is one way to establish its validity. However, they argue that testing it across cultures requires a priori assumptions because, by its very nature, a theory represents a priori judgment. In their eyes, this is essentially what Sun et al. (2018) did. They took an a priori definition (i.e., a theory) of legitimacy and “attempted to test whether the data are consistent with the expectation from the theory.” Because of this, Jackson and Bradford (2019) are wrongly accusing them of imposing:

‘…an Anglo-Saxon perspective [of legitimacy] under the smokescreen of empirical discovery’ (Jackson and Bradford 2019, p. 21). If this conduct is condemned in conducting research, most of our tests of theory, especially testing theories developed in the West in a different culture or vice versa, are all guilty. (Cao and Graham 2019)

Moreover, the argument that Sun et al. (2018) imposed an Anglo-Saxon meaning to legitimacy is problematic on its own merits because:

Even in authoritarian societies like China, most people in today’s global world seem to know what the police should and should not do. To test whether they, in fact, know this is genuinely empirical, not “the smokescreen of empirical discovery” (Jackson and Bradford 2019, p. 21). Bottoms and Tankebe (2012, p. 145), citing Beetham’s (1991) claim, note that audience legitimacy is “common to all societies.” The legitimacy of police norms, ipso facto, has been forming internationally. It is, therefore, nearly universal.

Nearly the entire critique of Cao and Graham (2019) on this issue stems from misunderstandings and/or misrepresentations of Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) argument. First, Jackson and Bradford do not argue that “the content of legitimation (i.e., the bases of which legitimacy is justified or contested) are an empirical question”. Cao and Graham (2019) pulled this partial quote from Jackson and Bradford’s explanation of the distinction between normative legitimacy and empirical legitimacy. A fair reading of this discussion shows that the partial quote provided by Cao and Graham does not represent Jackson and Bradford's “argument,” but rather their description of the empirical approach to conceptualizing legitimacy, which they discuss after providing a description of the normative approach. Importantly, at no point in their paper do they say that one approach is necessarily better than the other. In fact, they explicitly note that the normative approach “may be a reasonable position, albeit it is not to our own particular taste—we prefer to empirically discover the culturally contingent criteria of legitimation that people in a particular political community actually use” (Jackson and Bradford 2019, p. 21). Furthermore, Jackson and Bradford are not arguing that legitimacy cannot be studied with an a priori definition either. Rather, their argument is that legitimacy researchers should not select a normative definition of legitimacy and then claim that they have found empirical support for that definition on the basis of a statistical technique that cannot provide that support.

Second, it is disingenuous to say that Jackson and Bradford justified their argument by pointing to cultural sensitivity. First and foremost, the entire argument in their paper is justified on (1) the fact of what CFA as an analytical technique can and cannot show and (2) the conceptual distinction between normative and empirical legitimacy. Moreover, Jackson and Bradford’s argument that Sun et al.’s (2018) approach lacks cultural sensitivity was in response to one of their justifications for using the Tankebe approach in the first place:

Tankebe also expressed a high level of cultural sensitivity in his discussion of legitimacy…[He] emphasized the dynamic nature embedded in police–citizen encounters, arguing that the different dimensions of legitimacy tend to have different effects across societies and among social groups within the same society. It is with this same embracement of cultural diversity that we attempt to test Tankebe’s work in the Chinese context” (Sun et al. 2018, p. 279)

Yet for some reason, Cao and Graham (2019) accuse Jackson and Bradford of justifying their argument with “trendy criminology.”

Third, Jackson and Bradford (2019) do not “advocate that empirical legitimacy must tie to a local culture and when testing legitimacy in a new context, one must not assume any prior concept for the locals” (Cao and Graham 2019, emphasis mine). Rather, this will be the strategy of anyone using an empirical approach to conceptualize legitimacy. By definition, empirical legitimacy does not place normative criteria on the meaning of legitimacy, regardless of whether we are discussing a new or old context. Instead, it requires one to leave it an open empirical question as to what factors legitimate the authority in question. Thus, it is not the case that Jackson and Bradford (2019) are advocating that legitimacy must only be studied in a bottom-up manner from culture to culture. Whether one takes a bottom-up approach or top-down approach ultimately depends on whether they are conceptualizing legitimacy with an empirical or normative strategy. While Jackson and Bradford prefer the former strategy, they recognize that legitimacy scholars can take the latter approach should they choose, so long as those scholars are not utilizing CFA to provide “empirical” support for their normative conception.

Fourth, the fundamental critique of Jackson and Bradford (2019) of Sun et al. (2018) is that CFA cannot actually “test whether the data are consistent with the expectation from the theory” (Cao and Graham 2019). As they explained, in this instance, the data are also consistent with Tyler’s theory of legitimacy. While I do not claim to know how Jackson and Bradford would answer the question of how a researcher should conduct an empirical test of a theory, I would assume that part of their answer would entail avoiding analytical techniques that are not capable of “empirically testing” the normative theory in question. Ultimately, this is the basis for their argument that Sun et al. (2018), in practice, imposed an Anglo-Saxon perspective of legitimacy under the guise of empirical discovery. The four-component model Sun et al. (2018) employed is deeply rooted in liberal democratic traditions from the West, particularly England (Bottoms and Tankebe 2012; Tankebe 2013). Sun et al. (2018) used these normative criteria to define what legitimacy means in the Chinese context. They pointed to their CFA results as empirical support for that definition, but CFA cannot provide this support. Given their inability to determine empirical support, they have imposed—rather than tested—an Anglo-Saxon perspective on what legitimacy means among their Chinese participants.

Finally, if Cao and Graham (2019) are going to argue that “most people in today’s global world seem to know what the police should and should not do,” then they are going to need to provide a review of truly empirical work that have established these universal policing norms on a global scale. To date, the existing empirical literature does not support their claim of universality in the meaning of legitimacy (e.g., Bradford et al. 2014; Jackson et al. 2014a, b; Smith 2007; Sun et al. 2017; Tankebe 2009). Furthermore, I find it telling that they cite page 145 from Bottoms and Tankebe’s (2012) discussion of Beetham’s claim that audience legitimacy is “common to all societies,” given that the first time Bottoms and Tankebe discuss this claim is on page 131 of their article. However, on that page they provide a more complete version of the quote noting that Beetham provided a conceptual framework of legitimacy that captures “an underlying structure of [audience legitimacy] common to all societies, however much its content will vary from one to the other” (emphasis mine). Contrary to Cao and Graham’s insinuations, Beetham never argued for a set of universal norms (at least according to Bottoms and Tankebe 2012). Rather, he argued for a universal structure of legitimacy that revolved around (1) legal validity, (2) shared beliefs, and (3) expressed consent. In other words, he recognized that the content within that structure (i.e., the normative criteria) would necessarily vary from one culture to the next. Additionally, I can agree with Cao and Graham that testing whether or not people have knowledge of different policing norms could potentially be seen as “genuinely empirical.” However, if Cao and Graham (2019) are implying that knowledge of those norms represents universal components of legitimacy, then they are, ipso facto, utilizing a normative approach to conceptualize legitimacy. Moreover, if they use the results from CFA to support their argument they are not, in fact, engaging in genuine empiricism, but rather blowing the same “smokescreen of empirical discovery” (Jackson and Bradford 2019, p. 21).

Measuring Legitimacy

Cao and Graham (2019) note that there is no consensus on how legitimacy should be measured and that this is partially responsible for the current debate. On their account, Sun et al. (2018) used an alternative conceptual scheme to Tyler’s (2006) approach based on three pieces of information:

First, it was inspired by Bottoms and Tankebe’s (2012) brilliant analysis of legitimacy in which the authors concluded that Tyler’s definition of legitimacy does not cover all possible components of audience legitimacy. Second, the measurement comes directly from the prior study conducted by Tankebe (2013) and published in the top journal of the field Criminology…Third, Sun et al.’s adoption of the measure was assisted by their own analysis of the data. That is, confirmative factor analysis (CFA) indeed supports this scaling. (Cao and Graham 2019)

Given these three facts, Cao and Graham (2019) wonder what the logical ground is for Jackson and Bradford’s (2019) opposition to this strategy. They surmise that the objection is based “not on the clarification of the concept of legitimacy, but on the traditional/charismatic authority.” Essentially, Jackson and Bradford are critical of Sun et al.’s strategy because it challenges the traditional and charismatic authority of Tom Tyler. To support this claim, they note that Jackson and Bradford (2019):

…cited Tyler and his colleagues’ works as ‘the standard approach to studying empirical legitimacy’ forgetting their own statement that ‘Legitimacy is an abstract and unobservable psychological construct, and there are numerous ways to operationalize the perceived right to power, aside from the standard ways of institutional trust and/or normative alignment and/or obligation to obey (Tyler and Jackson 2013’ (p. 22-23). (Cao and Graham 2019)

However, as Cao and Graham (2019) lecture “…in testing a theory, researchers deduce propositions from the theory, formulate hypotheses, and test them against the data,” while always striving to question everything about the validity of an argument. From their perspective, this is what Sun et al. (2018) are guilty of doing: following the scientific method. Given their use of this process, Cao and Graham (2019) conclude: