Abstract

This paper examines the relationship of entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) and entrepreneurial intention in the Turkish culture. Sub-dimensions of ESE were investigated and the level of entrepreneurial intention was discussed. The sample comprised of 245 undergraduate students of a university in Turkey. Results suggest that students have a high intention to be entrepreneurs. ESE has a strong effect on entrepreneurial intention, but sub-dimensions of ESE have different impacts. The results of the study were compared with a previously published study conducted in the USA and Korea by a group of researchers. In this comparison, the national cultural context was considered as an influential factor in entrepreneurship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a complex process comprised of significant elements according to the various studies on entrepreneurship. Creation and maintenance of a successful venture is a function of individual factors, such as the competency and the motivation of the entrepreneur and the contextual factors, such as the environment where entrepreneurship is developed. Though contextual factors have significant effects on entrepreneurship activities, the entrepreneurship phenomenon is composed of individuals. So, individual differences are stressed in distinguishing entrepreneurs and revealing successful ones. In this context, individual dispositional factors are emphasized such as work displacement, prior work experience, need for achievement, locus of control, superior social skills and personal determination (Markman and Baron 2003; Luthans and Ibrayeva 2006). However, studies investigating the entrepreneur characteristics have not produced concrete results. Thus, factors such as intentional decision making, work activity, and rational evaluation of the situation need to be investigated further as individual factors. One of the important constructs regarding intentional decision making is entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE) (Chen et al. 1998; Jung et al. 2001).

The role of self-efficacy has been stressed in studies regarding entrepreneurship. Self-efficacy is an individual’s cognitive estimate of his/her capabilities to mobilize resources, activity and motivation that is required to control the events in his/her lives. One important impact of self-efficacy is the preference for certain behaviours. Individuals tend to choose situations in which they anticipate high personal control and avoid situations in which they anticipate low control. For this reason, people determine and choose career paths according to their perceptions about their capacities. In a sense, the assessment of personal capacity directs individuals to prepare for and enter occupations in which they feel efficacious but avoid occupations in which they feel incompetent (Chen et al. 1998).

Launching a venture or starting one’s own business is generally defined as an intentional and purposive action. Together with many individual and environmental factors, self-efficacy of the entrepreneur is an important antecedent in terms of intention because self-efficacy of the entrepreneur affects his/her career choice and development (Chen et al. 1998). However, few studies have been conducted to test this hypothesis. Thus, entrepreneurial intention and ESE perception are the focus of this study.

The relationship between ESE perception and entrepreneurial intention has been discussed in several studies (Chen et al. 1998; Jung et al. 2001; Kickul and D’Intino 2005). However, studies have generally been conducted in the U.S. but the cultural environment of the society might have effects on ESE perception. The aforementioned relationship deserves investigation because the national infrastructure and culture might play notable role in the determination of motivational infrastructure. For instance, in the U.S.A, where individualism is high and uncertainty avoidance is low, self-efficacy perception to initiate an enterprise may motivate the individual. On the contrary, in Turkey, where collectivism and uncertainty avoidance is high, national culture might decrease self-efficacy.

Launching a new venture is a social process, because the entrepreneur is at the interaction with other people in the society while gathering the required resources so as to find the opportunity. Also, the social environment, from the point of socio-psychological context, has important effect on the motivation, perception and attitude of the individual. Within this framework, ESE belief may be considered as an attitude towards launching a new venture in a specific social environment (Jung et al. 2001). This attitude is affected by the values and norms of the society. The values, norms and standards of behaviour are shaped within the concept of culture (Pistrui et al. 2000; Naktiyok 2004). As a consequence, the entrepreneurial activity may or may not be seen as one of the standards of behaviour in a country due to both positive and negative conditions for entrepreneurship provided by cultural values and beliefs of that country (Morrison 2000a). In other words, every culture has different priorities, and a value that is important for one culture may not be important for another.

It is agreed by researchers that individualist culture which is characterized by freedom and autonomy stimulates independence, personal responsibility and innovation, and creates an environment that reinforces the entrepreneurial activity. On the other hand, it is agreed that collectivist culture will contribute to uncertainty avoidance, increase resistance to change and provide group orientation, so it will not create positive conditions in terms of entrepreneurship (Jung et al. 200; Siu et al. 2007). For instance, in a study conducted among undergraduate students in nine different countries, it was found that in the individualist culture, where internal locus of control is high and uncertainty avoidance is low, cultural values supported entrepreneurship orientation (Mueller and Thomas 2000).

Uncertainty avoidance is another dimension of national culture and it reflects the point of view for uncertain situations. It also implies the degree of importance that people attach to current norms and stability. High uncertainty avoidance causes intolerable anxiety in trying something new that has uncertain outcomes (Jung et al. 2001). So, in countries where uncertainty avoidance is low, individuals will tend to accept the likelihood of failures and be able to struggle through failures so as to gain important outcomes in the future (Jung et al. 2001). On the other hand, stability is valuable in communities where uncertainty avoidance is high. People in these communities attach importance to job security, formative and written procedures and adhere to the absolute facts so as to make life more secure (Adler 1991). Individuals are in pursuit of stability, authority, hierarchy and tend to bind up formative procedures and are afraid of suspicious and risky positions (Sargut 2001). Initiating a new venture in these cultural contexts is not seen as a valuable career path (Jung et al. 2001).

In addition to the cultural dimensions of individualism-collectivism and uncertainty avoidance, the dimensions of power distance and masculinity have impacts on ESE belief. In the communities where power distance is high, people who have less power are dependent on more powerful people. People having more power than others are privileged and they use their initiatives to decide whether something is right or wrong (Uyguc 2003). People living in communities where power distance is low interact and contact in equal positions (Hofstede 1993). Low power distance positively impacts characteristics associated with entrepreneurship such as self confidence and initiative.

Flexibility, equality, quality of life, regularity, working for living and dependency are important in societies where ‘feminine’ values are dominant. On the other hand, performance, living for working, independency, money and materialism are important in societies where ‘masculine’ values are dominant (Sisman 2002). Masculine values symbolize spirit of competition, determination and wealth, so they influence entrepreneurial intention in countries where entrepreneurial thought has emerged (Morrison 2000b). For instance, a study revealed a positive relationship between the values such as change orientation and competitiveness, and launching a new venture (Davidsson and Wiklund 1997).

The relationship between ESE perception and entrepreneurial intention will be investigated in Turkey where its own cultural characteristics have impacts on the entrepreneurial thought. Turkish culture can be defined as a high context culture which is collectivist versus individualist, characterized by feminine values instead of masculine values, high power distance and high uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede 1980; Sargut 2001). So, a low level of relationship is anticipated between ESE perception and entrepreneurial intention in Turkey when compared to the USA. The main aim of this study is to find out the relationship between ESE perception and entrepreneurial intention. Specifically, the answers of these questions will be figured out.

-

1.

What is the relationship of ESE perception and entrepreneurial intention in the Turkish cultural context?

-

2.

What is the degree of ESE perceptions of the students in the study?

-

3.

What is the degree of entrepreneurial intentions of the students in the study?

The construct of self-efficacy

Self-efficacy belief is the focal point for social learning theory that explains the individual behaviour through the mutual cause-effect relationship among personal characteristics, environmental factors and behaviour (Chen et al. 1998; Shea and Howell 2000; Hartsfield 2003). Self-efficacy belief, that is used to explain human behaviour by Bandura, one of the theorists of social learning theory, implies “the belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Bandura 1997). Besides, self-efficacy is the reliance of an individual on his/her competencies to perform, and one’s judgement of “how well one can execute courses of action required to deal with prospective situations”(Bandura 1982).

Self-efficacy is a motivational source that is related to an individual’s trust and belief on his/her capability to accomplish and it affects the cognition level of the individual (Harrison et al. 1996; Van Oudenhoven and Van der Zee 2002; Kuoa et al. 2003). Self-efficacy belief, reflecting the trust on one’s capabilities, is a kind of self assessment that affects efforts and determination to be set forth against the obstacles and towards the decisions related to the activities that will be performed (Hsu and Chiu 2004). This is to say that self-efficacy includes both the beliefs about the individual competency that affects the work and the beliefs about the activities which are successfully performed will result in specific outcomes (Bandura 1977; Tsang 2001). If these beliefs are positive, the individual will organize the activities in such a way that will be successful. On the contrary, when beliefs are negative, even if the individual has required skills, s/he will feel failure anxiety because of the doubts about his/her capability, and s/he will either unlikely perform the behaviour or will not insist on maintaining the behaviour when faced with obstacles (Hartsfield 2003). From this point, self-efficacy belief is a means to understand why individuals having similar knowledge and competency act differently (Milstein 2005).

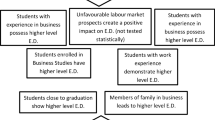

Self-efficacy belief is dynamic and changeable because it is based on four fundamental information sources that interact with each other. These information sources are as follows (Lent et al. 1996; Anderson and Betz, 2001; Mak and Tran 2001; Day and Allen 2004; Peterson and Arnn 2005):

-

1

Personal Accomplishments (mastery experiences): The successful or unsuccessful outcomes of previous experiences influence the self-efficacy perception of an individual.

-

2

Experiences of others (vicarious experiences): Observing success of others strengthens self-efficacy, but observing failures of others has negative impact on self-efficacy.

-

3

Verbal Persuasion: The incentive and encouragement provided by others can persuade an individual that s/he has the required capability to do something.

-

4

Physiological and Emotional Arousal: Physiological and emotional impressions which are felt during the execution of an action, such as anxiety, stress, arousal and fatigue influence self-efficacy because people can perceive them as useless symptoms.

Although self-efficacy belief has similarities with other socio-cognitive phenomena such as locus of control, need for achievement, self confidence and self esteem, the major difference of self-efficacy belief stems from the fact that it is a structure that implies instantaneous belief and assessment of the individual about a special task or capacity. So, an individual might have a higher self-efficacy belief for one task and lower for another. For instance, the individual may feel low efficacious in creating an enterprise, but high efficacious in climbing up mountains. Locus of control and need for achievement state the general expectation of the individual, and self confidence states the entire capability and the general feeling (Delmar 2000; Jung et al. 2001; Peterson and Arnn 2005). Again, while self esteem includes one’s degree of self appreciation, self-efficacy includes the perception of an individual about the capability of accomplishing a task (Peterson and Arnn 2005).

Self-efficacy and career choice

As self-efficacy is an important antecedent of behavior, it influences an individual’s attitudes and behaviors about career choice and career development. People choose careers in areas in which they feel most competent and avoid those in which they feel less competent or less able to compete. People who feel themselves competent for an occupation tend to choose that occupation, prepare themselves much better for the career, and are more committed to and successful in their careers (Lent et al. 1996; Bandura et al. 2001; Pinquart et al. 2003). Generally, individuals with higher self-efficacy tend to choose careers in which they will be able to create new opportunities and act proactively because of their higher goals and success expectation, insistence on solving problems and fighting against threats with passion (Pinquart et al. 2004; Forbes 2005).

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and the study of entrepreneurship

Individuals and their behavioural processes are the first concepts that appear when entrepreneurship is discussed. For this reason, individuals with higher ESE belief are likely to be entrepreneurs. ESE belief can be defined as the perception of an individual about the capabilities of being an entrepreneur and the belief for performing entrepreneurship roles and tasks successfully (Boyd and Vozikis 1994; Chen et al. 1998; Forbes 2005; Luthans and Ibrayeva 2006).

ESE belief is an explanatory variable that determines the power of the entrepreneurial intention and the possibility of this intention resulting in an entrepreneurial activity, so it differentiates entrepreneurs and others (Boyd and Vozikis 1994; Chen et al. 1998; Markman and Baron 2003). High ESE is one of the prerequisites of potential entrepreneurs. Although high self-efficacy individuals evaluate the business environment as full of opportunities, low self-efficacy individuals perceive the same environment as full of obstacles.

According to the studies by Krueger et al., perceived self-efficacy affects feasibility and results in intention at the end. (Krueger et al. 2000). Theory of planned behaviour was first launched by Ajzen (1991). In this theory, likelihood of behaviour is related to the individual’s intention about that behaviour. Intention is stereotyped by the attitude of the individual. The existence of the attitude is determined by the perception regarding how the behaviour will feasibly lead to desired outcomes, acceptability of the outcomes according to social norms of a reference group and the desirability of the outcomes (Sharma et al. 2003).

Feasibility is the degree of one’s “I can do it” feeling in embarking on a task. Perception of feasibility guides the choice of career (Krueger et al. 2000), because it is the cognitive arena that will facilitate or undermine the execution of behaviour. The perceived feasibility increases the self-efficacy belief. From this end, self-efficacy belief of the individual, that is perceived to execute the required activities for the entrepreneurship, positively affects the entrepreneurial intention.

ESE belief increases the intention of launching a new venture according to the researches. For instance, in a study on 140 undergraduate students, it was found that there was a positive and significant relationship between ESE perception including entrepreneurial skills such as marketing, innovation, management and financial control, risk taking, and entrepreneurial intention. The researchers argued that ones with higher self-efficacy evaluated the entrepreneurial opportunities better and could be able to see positive outcomes (Chen et al.1998). Similarly, it was reported that self evaluation capability had direct effects on launching a venture (Chandler and Hanks 1994). In a study performed on 272 students, it was indicated that there was a significant and positive relationship between ESE perception, including risk and uncertainty management, innovation and product improvement, interpersonal relations and network management, opportunity recognition, finding resources, developing and maintaining the innovative business environment and entrepreneurial intention (De Noble et al. 1999). Again Jung et al. used the questionnaire developed by De Noble et al. and reached comparable results within a study on 379 students in the U.S and 351 students in the South Korea (Jung et al. 2001).

Methodology

Participants and procedures

The population of this study consisted of undergraduate students of the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences at Ataturk University in the 2006–2007 academic year. The study was conducted on students due to the fact that undergraduate students mostly represent the potential entrepreneurs both in the developed and developing countries. The students graduating from higher education institutions find themselves in a changing and unstable environment in Turkey. Today, there is no stability in employment. The traditional career path has changed and the idea of self employment as a career choice has strengthened. Besides, expectations of the employers have changed; they want the graduates perform entrepreneurial activities and adopt innovative attitudes. Within this manner, undergraduate students must perform the entrepreneurial role model much more than before, must have positive thoughts about entrepreneurship and they must execute entrepreneurial applications.

Data were gathered through a questionnaire survey. The total number of students at the faculty in the aforementioned year is 1775. From this population, 316 students were selected randomly — 95 % confidence level at 5 % margin of error (Saunders et al. 2003; http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm). Questionnaires were distributed to sample undergraduates by hand. In the end, 288 questionnaires were returned and 43 questionnaires were ignored because of the high amount of missing data. Thus, 245 questionnaires were considered for statistical analyses (response rate of 74%).

Instruments

The fundamental roles and tasks of the entrepreneur are related to complex issues in association with economical, social and managerial contexts. These roles and tasks include the recognition of job opportunities, gathering required physical and non-physical factors in order to benefit from these opportunities, choice of the legal form of the enterprise, definition of mission and vision statements, shaping culture and structure, development of the products and services, recognition and fulfilment of market needs, risk taking, gaining support of all related internal and external groups, managing information, assessing the environmental factors, creating, developing and transforming the venture. (Naktiyok 2004). For this reason, self-efficacy perception is generally defined as the belief on the capability of performing entrepreneurial activity with regard to the evaluation of managerial, functional and technical capabilities of the individual. Two different scales are mostly used in previous research. First scale was developed by Chen et al. to evaluate the marketing, innovation, management, risk taking and financial control skills of individual. (Chen et al. 1998). The second scale was developed by De Noble et al. after negotiating with entrepreneurs and consisted of 35 items (De Noble et al. 1999; Kickul and D’Intino 2005). Explanatory factor analysis was applied to the scale and ESE perception was evaluated with 22 items having more than 0.40 factor loadings (De Noble et al. 1999). The scale indicated six major dimensions of ESE perception. The dimensions are as follows; developing new product or market opportunities (skills related with opportunity recognition), building an innovative environment (skills related with the capacity to encourage others), initiating investor relationships (skills related with obtaining funds to capitalize the start-up company), defining core purpose (mission and vision creation and communication skills to attract key staff and investors), coping with unexpected challenges (skills to cope with risky and uncertain situations), developing critical human resources (skills to employ and develop human resources). This scale was used in our study to measure ESE, considering the results of the explanatory factor analysis and its frequent use in previous studies. An explanatory question was headed at the beginning of the questionnaire: “How capable do you believe you are in performing each of the following tasks?” The respondents were asked to indicate their responses for each item on a five point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

The entrepreneurial intentions of the respondents were evaluated by four items: “I will probably own my own business 1 day”, “ It is likely that I will personally own a small business in the relatively near future”, “Being ‘my own boss’ is an important goal of mine”, “I often think of having my own business”. The former two items were developed by Crant (1996), the others were developed by Kickul and D’intino (2005). Responses to these items were indicated on a five point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Respondents were also asked to provide their gender, occupations of their parents, income level of their family and their academic success since these demographic variables may be important in entrepreneurial thought.

Analyses and results

Reliability and validity of the instruments

First, the reliability and validity of the questionnaires were analyzed so as to acquire significant outcomes. When analyzed the returned questionnaires, it can be stated that the sample was broadly representative of the population and the sample selection was stringent to ensure generalizability and validity of findings in terms of statistical analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used as the reliability measure. Table 2 shows the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for each factor of entrepreneurial self efficacy scale which were determined after exploratory factor analysis. These values are the indicators for a reliable questionnaire (Gliem and Gliem 2003). Moreover, no increase was observed for the internal consistency of the scales in case of omitting an item. This finding also supports that the internal consistency in connection with the reliability of the scale has an acceptable level. Besides, when questionnaires get prepared, so as to provide the face validity of the scales, all items of the original scales were carefully translated and back-translated. Consequently, it was reported that no item in the scales has a meaning specific to a private cultural context.

Findings

Demographic characteristics of respondents

The percentages of male and female respondents were similar: 47 % were female (n = 115) and 53 % were male (n = 130). The frequency distribution of the occupation of father was as follows: 43 % were employed in the public sector (n = 98), 35 % were self employed (n = 79), 14 % working for other employers (n = 31), and 8 % were retiree or engaged in farming (n = 19). Eighteen students did not report occupation of their fathers. According to these findings, most of fathers work in the public sector, but self employed fathers also have an important percentage. Whilst 225 of the mothers are housewives (92 %), 13 of them are employed in public organizations (5 %), and two of them work for other employers (1 %). Only four of the mothers are self-employed (2 %). One student didn’t report occupation of mother.

When academic success of the students is taken into consideration; it is observed that 15 % of the respondents had honor degrees (n = 37), 10 % had higher degrees (n = 25) and 75 % had no degrees (n = 183). The frequencies of monthly income of family are as follows: 10 % had less than $ 404 (n = 24), 36 % had $ 405– $ 808 (n = 89), 31 % had $ 809–$ 1212 (n = 75), 11 % had $1213–$ 1615 (n = 26) and 13 % had above $ 1615 (n = 31).

Results of exploratory factor analysis

Factor analysis was applied to the 35 items of ESE measure using principal components analysis with varimax rotation so as to determine the dimensions. In the first stage, it was realized that two items were not loaded on any factor. In the second stage, two items were omitted and factor analysis was applied to 33 remained items again and it was resulted in six factors. These factors explain 63.42 % of the total variance.

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) was 0.93 and Bartlett’s test of Spherecity classified the data as adequate for analysis (4640,98, p < 0.000). Both Bartlett’s test of Spherecity and measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) ensured that the pre-requisites of factor analysis were met. Results of factor analysis are shown in Table 1.

As seen in Table 1, first factor includes eight items which refer to the belief that one is capable of opportunity recognition and new product development. This factor is named as “developing new product and market opportunities” and has an eigenvalue of 3.90. It explains 11.83% of total variance. The second factor composes of six items and named as “coping with unexpected challenges”. It illustrates the capability of coping with unexpected changes, has an eigenvalue of 3.88 and explains 11.76 % of total variance. The third factor, “developing critical human resources”, refers to the ability to recruit and benefit from human resources. It has an eigenvalue of 3.83 and explains 11.62 % of total variance. The fourth factor, “defining core purpose”, refers to the articulation of the vision and core values of the enterprise. It has an eigenvalue of 3.72 and explains 11.27 % of total variance. The fifth factor, “building an innovative environment” points to the creation of a climate supporting innovation in the organization. It has an eigenvalue of 3.07 and clarifies 9.30% of total variance. The last factor, “initiating investor relationships” focus on the capability to establish and sustain strong relations with investors. It has an eigenvalue of 2.52 and explains the 7.64 % of total variance.

Means, standard deviations and correlations

Table 2 presents the means of subscales of ESE, and entrepreneurial intention.

Table 2 also presents comparative results of a prior study conducted by Jung et al. in 2001 in USA and South Korea. The results of the comparison between Turkey, Korea and US samples might be interpreted by benefiting from the study conducted by Hofstede in 50 countries and three geographical regions, totally from 53 national cultures. When Turkey, USA and Korea are compared in terms of individualism-collectivism; whereas individualism is dominant in American culture, collectivism is dominant in Turkish and Korean cultures. If Turkish and Korean cultures are compared, Korean culture is more collectivist than the Turkish culture. In terms of power distance; Turkey has the highest power distance. On the other hand, Korea is in the culture group with high power distance and it is in a closer position to Turkey. USA is in a country group where power distance is low. Whilst Turkey and Korea are similar in terms of uncertainty avoidance; USA exists in a country group where uncertainty avoidance is low. With respect to masculinity; USA is the country where masculine values are dominant; followed by Turkey and Korea. However, both Turkey and Korea are in the group where feminine values are dominant (Sanyal 2001).

The findings of our study indicate that, in general, ESE perceptions of respondents are rather positive. The dimension of “defining core purpose” has the highest mean value (4.01) and the dimension of “coping with unexpected difficulties” has the lowest (3.44). In other words, students have strong beliefs in their capability and capacity to determine and articulate the goal and direction of the newly launched enterprise. However, their belief regarding the capability to cope with unexpected difficulties of the business life is quite low. This finding may be attributed to the students’ inexperience in business life. Students are aware of the threats and problems of the external environment and, they also lack experience in taking precautions. So, they might appraise themselves inadequate. Entrepreneurial intention which expresses students’ desire for launching a venture has a mean value of 3.73. Therefore, it can be maintained that students have high levels of entrepreneurial intention.

As illustrated in Table 2, when mean values of Turkish and US samples are compared, it is observed that Turkish students have more negative perceptions in terms of all dimensions of self-efficacy belief. But the perceptions of Turkish students in all dimensions of self-efficacy belief are more positive than Korean students. However; there is an interesting finding regarding entrepreneurial intention. Turkish students’ intention of launching a venture is higher than the students in Korea and even the US. This finding should be interpreted by considering the characteristics of Turkey. Unemployment rate is high in Turkey and the economic development has not decreased this rate as much as anticipated. Also, in general the levels of salaries are inadequate. Government policies, privatization and the growth of private sector make self employment more attractive since employment in public jobs has been difficult. So, the students in this study consider self employment as a good career choice.

Correlation coefficients pointing to the relationship between ESE perceptions and entrepreneurial intention for Turkish and Korean samples are presented in Table 3.

As illustrated in Table 3, it is realized that all relationships in the Turkish sample are significant and positive at the p < 0.01 level. In terms of the strength of the relationship, the dimension of “defining core purpose” has the strongest relationship with entrepreneurial intention (r = 0.53). The dimensions having the weakest relation with entrepreneurial intention are “coping with unexpected challenges” (r = 0.38) and “initiating investor relationships” (r = 0.38). When the correlations for Turkish and Korean samples are compared, it can be stated that the coefficients regarding Turkish sample are higher. In other words, the relationship between ESE perception and entrepreneurial intention of the students in Turkey is stronger than their Korean counterparts. Table 4 shows the coefficients for Turkey and USA.

As is seen, the relationship between ESE perception and entrepreneurial intention is higher in the US sample than the Turkish sample. This finding agrees with our expectation, because it is known that the societal context and the cultural characteristics of Turkey do not foster entrepreneurship. For this reason; although an individual may think that s/he has adequate competencies, factors other than belief on one’s capability to launch a venture is expected to be more effective in entrepreneurial intention.

Regression analysis

Having satisfactorily understood that there is a significant relationship between ESE and entrepreneurial intention; regression analysis is applied to evaluate the direction of the relationship. For this aim, dimensions of ESE are considered as an independent variable and entrepreneurial intention is treated as the dependent variable. Table 5 summarizes the results of the regression analysis.

Table 5 shows that four dimensions, developing new product and market opportunities, building an innovative environment, defining core purpose and coping with unexpected challenges, have significant and positive effects on entrepreneurial intention. On the contrary, the effect of the dimensions of “initiating investor relations” and “developing critical human resources” is not significant. The equation is significant as a whole and explains 34 % of the variance in entrepreneurial intention.

Discussion

This study yields useful results in terms of the socio-psychological view for entrepreneurship. There is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial intention and ESE; so the concept of self-efficacy deserves more attention in entrepreneurship research. Also, the study evaluates the results in a culture where collectivism and uncertainty avoidance are high. Even though these cultural characteristics do not foster entrepreneurship, the moderate to high relationships between dimensions of ESE and entrepreneurial intention show that the concept of self-efficacy may be fruitful in determining the factors that affect entrepreneurial intention. The dimensions which are related weakly to entrepreneurial intention points out that apart from ESE, there are other important factors. In Turkey, one of the other factors that affect entrepreneurial decision may be the policies of national institutions that regulate new business start-ups. These institutions might slow down or undermine the entrepreneurial process because of their highly bureaucratic nature. The individual might believe that s/he is capable of executing actions required for launching a new venture; but he might also be convinced that he is not capable of overcoming the barriers of the legal proceedings.

Another point that deserves investigation is the current situation of entrepreneurship education in Turkey. Entrepreneurship education is becoming more and more important in leading young people to entrepreneurship. But most courses in entrepreneurship focus on technical tasks and ignore the issues such as entrepreneurial thought, cultural constraints on entrepreneurship and the individual characteristics shaped with the interaction of the individual and society. Thus, courses on entrepreneurship should focus more on socio-psychological and cognitional concepts such as self-efficacy. By this way, students can simultaneously detect their entrepreneurial potential and assess the impact of social and cultural characteristics. Hence, this potential can be improved by leading these students appropriately and helping them remove their incompetence.

Limitations

While the findings of this research present many useful results, several of the study’s limitations must be noted. First, the research subjects are students, not real-world-entrepreneurs. Using a sample of students can provide important information on ESE and entrepreneurial intention of youths in Turkey. However, it is very important to support the findings of this study with future research that examines these constructs on a sample of real-world entrepreneurs. Moreover, this research was conducted only in one faculty of a university. In the future, more comprehensive research should be done in more geographically dispersed areas and in different faculties of universities.

Second problem is the conceptualization of the constructs and measurements from the original instrument with the American approach of entrepreneurial processes. Social and cultural context is an undeniable factor that shapes entrepreneurial processes in a country. Therefore, additional research using interviews and other forms of qualitative data should be done before we can disclose the role of ESE in entrepreneurship in Turkey.

Potential social desirability in reporting self-efficacy is another problem. Before completing the questionnaires, respondents were told that reporting realistic evaluations are vitally important in terms of gaining valuable insights by this study. Despite all the precautions taken, social desirability might have affected the choice of positive evaluations of entrepreneurial self- efficacy. So, future research should think of ways to reduce potential social desirability.

The data used in this research is cross-sectional in nature and causal inferences are not appropriate. Therefore, it is possible only to conclude that entrepreneurial intention is positively related with the dimensions of ESE. Future research should utilize a longitudinal design in order to infer causal linkages among aforementioned variables. Also, in this study, there was no question that seeks to determine whether respondents do anything in order to actualize their entrepreneurial intention. Questions about actual preparation for self employment will clarify the association between ESE and entrepreneurial intention. So, future research should measure actual preparation for entrepreneurship.

Finally, in this study, cultural orientation of Turkey was taken for granted and Hofstede’s (1980) classification of national cultures was used as a directional tool so as to comment on the relationship between culture and entrepreneurship. In fact, future research should verify this assumption that Turkish culture still remains in the presupposed cultural dimensions such as collectivism versus individualism and femininity versus masculinity. In other words, future research should measure cultural orientation and compare its findings on a more robust ground with other studies conducted in distinctive cultures.

References

Adler, N. J. (1991). International dimensions of organizational behavior. Boston: PWS Kent Publishing.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Anderson, S. L., & Betz, N. E. (2001). Sources of social self-efficacy expectations: Their measurement and relation to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58, 98–117.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children's aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72(1), 187–206.

Boyd, N. G., & Vozikis, G. S. (1994). The influence of self-efficacy on the development of entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 18, 63–90.

Chandler, G. N., & Hanks, S. H. (1994). Founder competence, the environment and venture performance. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 18(3), 77–90.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 295–316.

Crant, J. M. (1996). The proactive personality scale as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 34, 42–49.

Davidsson, P., & Wiklund, J. (1997). Values, beliefs and regional variations in new firm formation rates. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18, 179–199.

Day, R., & Allen, T. D. (2004). The relationship between career motivation and self-efficacy with protege career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64, 72–91.

Delmar, F. (2000). The psychology of the entrepreneur. In S. Carter & D. Jones-Evans (Eds.), Enterprise and Small Business (pp. 132–154). England: FT-Prentice Hall.

De Noble, A.F., Jung, D., & Ehrlich, S.B. (1999). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: The development of a measure and its relationship to entrepreneurial action, frontiers for entrepreneurship research. Retrieved from http://www.babson.edu/entrep/fer/papers99/I/I_C/IC.html.

Forbes, D. P. (2005). The effects of strategic decision making on entrepreneurial self-efficacy (pp. 599–626). Theory and Practice, September: Entrepreneurship.

Gliem, J. A., & Gliem, R. R. (2003 October). Adult, continuing, and community education. Paper presented at the Midwest Research to Practice Conference in the Ohio State University, October 8–10, Columbus, OH.

Harrison, J. K., Wick, M. C., & Scales, M. (1996). The relationship between cross-cultural adjustment and the personality variables of self-efficacy and self-monitoring. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(2), 167–188.

Hartsfield, M. (2003). The internal dynamics of transformational leadership: effects of spirituality, emotional intelligence, and self-efficacy. Submitted to Regent University School of Leadership Studies: Unpublished Doctorate Thesis.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. (1993). Cultural constraints in management theories (pp. 91–94). February: The Executive.

Hsu, M., & Chiu, C. (2004). Internet self-efficacy and electronic service acceptance. Decision Support Systems, 38, 369–381.

Jung, D. I., Ehrlich, S. B., De Noble, A. F., & Baik, K. (2001). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and its relationship to entrepreneurial action: a comparative study between the US and Korea. Management International, 6(1), 41–53.

Kickul, J., & D'Intino, R. S. (2005). Measure for measure: modeling entrepreneurial self-efficacy onto instrumental tasks within the new venture creation process. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 8(2), 39–47.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intensions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411–432.

Kuoa, F. Y., Chub, T. H., Hsuc, M. H., & Hsieh, H. S. (2003). An investigation of effort—accuracy trade-off and the impact of self-efficacy on web searching behaviors. Decision Support Systems, 1065, 1–12.

Lent, R. W., Lopez, F. G., Brown, S. D., & Gore, P. A., Jr. (1996). Latent structure of the sources of mathematics self-efficacy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49, 292–308.

Luthans, F., & Ibrayeva, E. S. (2006). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy in Central Asian transition economies: quantitative and qualitative analyses. Journal of International Business Studies, 37, 92–110.

Mak, A. S., & Tran, C. (2001). Big five personality and cultural relocation factors in Vietnamese Australian students' intercultural social self-efficacy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 25, 181–201.

Markman, G. D., & Baron, R. A. (2003). Person—entrepreneurship fit: why some people are more successful as entrepreneurs than others. Human Resource Management Review, 13, 281–301.

Milstein, T. (2005). Transformation abroad: sojourning and the perceived enhancement of self-efficacy. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 217–238.

Morrison, A. (2000a). Entrepreneurship: what triggers it? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research, 6(2), 59–71.

Morrison, A. (2000b). Initiating entrepreneurship, enterprise and small business. In S. Carter & D. Jones-Evans (Eds.), enterprise and small business (pp. 97–114). England: FT-Prentice Hall.

Mueller, S. L., & Thomas, A. S. (2000). Culture and entrepreneurial potential: a nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness. Journal of Business Venturing, 16, 51–75.

Naktiyok, A. (2004). İç Girişimcilik. İstanbul: Beta.

Peterson, T. O., & Arnn, R. B. (2005). Self-efficacy: the foundation of human performance. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 18(2), 5–18.

Pinquart, M., Juang, L. P., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2003). Self-efficacy and successful school-to-work transition: a longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 63, 329–346.

Pinquart, M., Juang, L. P., & Silbereisen, R. K. (2004). The role of self-efficacy, academic abilities, and parental education in the change in career decisions of adolescents facing German unification. Journal of Career Development, 31(2), 125–142.

Pistrui, D., Welsch, H. P., Wintermantel, O., Liao, J., & Pohl, H. J. (2000). Entrepreneurial orientation and family forces in the new Germany: similarities and differences between East and West German entrepreneurs. Family Business Review, 3(3), 251–263.

Sanyal, R. N. (2001). International management: A strategic perspective. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Sargut, S. (2001). Kültürlerarası farklılaşma ve yönetim. Ankara: İmge.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2003). Research methods for business students. London: FT-Prentice Hall.

Sharma, P., Chrisman, J. J., & Chua, J. (2003). Succession planning as planned behavior: some empirical results. Family Business Review, 16(1), 1–16.

Shea, C. M., & Howell, J. M. (2000). Efficacy-performance spirals: an empirical test. Journal of Management, 26(4), 791–812.

Siu, O., Lu, C., & Paul, E. (2007). Employees’ well-being in greater china: the direct and moderating effects of general self-efficacy. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 56(2), 288–301.

Sisman, M. (2002). Orgutler ve Kulturler. Ankara: Pegem A.

Tsang, E. W. K. (2001). Adjustment of mainland Chinese academics and students to Singapore. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 25, 347–372.

Uyguc, N. (2003 May).Örgüt Kültürü ve Yönetim Davranışı. Paper presented at the 12th National Management and Organization Congress, Afyon, Turkey.

Van Oudenhoven, J. P., & Van der Zee, K. I. (2002). Predicting multicultural effectiveness of international students: the multicultural personality questionnaire. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 26, 679–694.

http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm. (The Survey System Sample Size Calculator, Retrieved December 27, 2007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Naktiyok, A., Nur Karabey, C. & Caglar Gulluce, A. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intention: the Turkish case. Int Entrep Manag J 6, 419–435 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0123-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-009-0123-6