Abstract

Background

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a largely wide used scale for sleepiness assessment. Measurement properties are studied in a sample of Portuguese adults, using different statistical procedures.

Methods

The sample consisted of 222 Portuguese adults (97 men and 125 women) with a mean age of 42 years old (SD = 12.5), 46 of which had obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) confirmed by polysomnography. The participants were assessed with the ESS, which was tested through a quantitative analysis based on the classical measurement theory (CMT) or the Rasch model (RM) conventions.

Results

A principal component factor analysis was performed according to the CMT, revealing a single factor explaining 39.92 % of the total variance of the scale. Internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s α coefficient was of .77. The mean of inter-item correlation was of .31 (.05 < r > .47), whereas the item-total correlations were considered good (.46 < r > .73). The ESS total score for OSA patients was significantly higher than healthy participants (p < .05). Overall data from the RM analysis was consistent with the guidelines of Linacre and essential unidimensionality was empirically corroborated (61 % the percentage of variance explained by the Rasch analysis). Model fit is adequate and the reliability coefficients for both items (.99) and subjects (.78) were considered good. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was also satisfactory (.78).

Conclusions

The ESS showed an adequate structural, internal, and criterion validity, both in the CMT and the RM, suggesting this as a useful and effective measure for assessing sleepiness in Portuguese adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a quantitative method to evaluate sleepiness or the propensity to fall asleep in eight everyday life situations, through a Likert scale [1–4]. This instrument has been used in different contexts, populations, and clinical conditions, with particular interest in respiratory sleep disorders [5–7]. Several versions of the ESS have been validated for different languages and populations, mainly to Portuguese (from Brazil), Chinese, French, German (from Switzerland), German (from Germany), Greek, Italian, Japanese, Korean, English (from New Zealand), Norwegian, English (from USA), Spanish (from Peru), Serbian, Spanish (from Spain), Thai, Turkish, and Spanish (from Mexico) [8–27]. Although the majority of these studies have been conducted with classical measurement methods, overall results have indicated good measurement properties of previous versions of the ESS [28–30]. Some studies have also demonstrated the suitability of this instrument through confirmatory factor analysis [31] and Rasch analysis [32, 33].

Concerning validation studies of measurement health-related patients-reported outcomes, the relevance to assess its methodological quality has been increasing, mainly in terms of the instrument’s measurement properties, standards for design requirements, and preferred statistical methods—The COSMIN checklist [34]. Through this checklist, a relative consensus from a large group of researchers [35] was reached on the inclusion of the following measurement properties: internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity (including face validity), construct validity (including structural validity, hypotheses testing and cross-cultural validity), criterion validity, responsiveness, and interpretability.

Despite the widespread clinical use of the ESS, there are no known studies that assess the psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of this scale in Portugal. Furthermore, the existing literature regarding the validation of the ESS is mainly based on classical measurement theory, neglecting the difficulty of scale items and the underlying characteristics of each individual. Thus, our primary goal is to validate a Portuguese version of the ESS in adults by using the classical measurement theory methods (CMT) and the Rasch model (RM) based on the item-response theory.

Methods and materials

Design and procedures

This study is based on a one-shot design. The required sample size was calculated a priori with Cohen’s d effect size for t tests. A total sample size of 220 participants was required for this study in order to detect a medium effect size (d = .40; 1 − β = .80; one-tailed α = .05) for an expected allocation ratio of .30. All subjects were volunteers (not paid) that gave their informed consent to the study objectives. The study was approved by the scientific and ethical committee of the clinical institutions where the subjects were diagnosed and treated for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Participants

The sample consisted of 222 Portuguese adults (97 men and 125 women). Forty-six of them (35 men and 11 women) were polysomnographically (type 1) diagnosed with untreated OSA, presenting different types of severity (measured by Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI), not positional). Patients were recruited from three public hospitals, while the remaining participants were healthy volunteers without a clinical diagnosis of OSA (62 men and 114 women), who were recruited from a sample community based (universities and companies) through convenience method.

Prior to enrollment, for the inclusion criteria, these subjects completed a short-form sleeping habits questionnaire, in which controls reported not having any diagnosis or symptoms of sleep disturbances. None of the subjects assessed (healthy participants and OSA patients) was a shift worker, had clinical history of any neurological or psychiatric disorders, or was doing any type of psychotropic medication.

Table 1 shows the basic demographic characteristics of the sample, as well as the AHI for the clinical sample of OSA.

The comparisons between healthy subjects and OSA patients showed statistically significant differences regarding age. Tukey HSD revealed statistically significant differences between healthy participants and OSA patients, but not between the groups of different OSA severity. As for the gender distribution, standardized residuals showed a difference in the gender distribution, particularly in subjects diagnosed with mild to moderate OSA.

Materials

Clinical history

As stated before, a short-form questionnaire was developed to assess the demographic variables, sleeping habits, and if there was a previously diagnosed sleeping disorder.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

The ESS consists of eight items, rated on a scale of 0–3, in which the total score is computed through the sum of item responses. The total score represents a measure of subjective daytime sleepiness (ranged 0–24, higher results indicate greater propensity to fall asleep).

The English version used of the ESS [3] was translated to Portuguese language by two different specialists in sleeping disorders, an independent neurologist and a neuropsychologist, and a native English speaker. The retroversion of the Portuguese version of the ESS was done by two other independent experts in sleeping disorders and a native in English language. The final translation of the ESS considered the most consensual designation for “dozing” which was translated to Portuguese as passar pelas brasas. This expression was chosen because it is used often in Portuguese language to describe a “nap” during the daytime.

Statistical procedures

Classical measurement theory

The psychometric properties through distribution measures, reliability, and validity were estimated according to the assumptions of the Classical Measurement Theory. In order to study data distribution, several descriptive measures were used, such as the mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and missing values. The structural validity was tested with principal component analysis (varimax rotation), whereas a Student’s t test for independent samples was performed to compare patients and healthy participants in criterion validity. Inter-item correlations were also conducted to study the internal validity. Reliability was tested under the Cronbach’s alpha procedure.

Rasch model

The Rating Scale Model (RSM) is an extension of the RM for polytomous items. These models transform ordinal response data of the subjects on an interval scale [36, 37] and are especially recommended for testing psychological assessment instruments [38] because of properties such as conjoint measurement of persons and items responses (i.e., parameters for persons and items are expressed in the same units). Moreover, the patterns of subjects’ responses are adjusted to the model (i.e., the probability of an item response depends only on the levels of person-item in the measured attribute) [39]. The RM is empirically useful in determining the quality of response categories in particularly in Likert-type scales [40].

Results

The classical methods to assess the effectiveness of the ESS were performed using the SPSS v.20 for Windows.

The item-response theory through Rasch model was conducted testing the Linacre guidelines [41]. This analysis was performed using the Winsteps 3.80.1 [42].

Classical measurement theory

Descriptive and distribution analysis

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for items and the total ESS.

The descriptive statistics indicate that there are no notable deviations in skewness and kurtosis on the total score of the ESS. There are, however, non-normal distributions for some individual items of the scale, with particular attention to item 6 (i.e., short range of values) and item 8, both showing moderate positive skewness and kurtosis. Furthermore, an analysis of missing values has clarified these results (i.e., three participants failed to respond to item 8).

Structural validity

To study the structural validity of the ESS, a factor analysis with a principal component analysis method was performed using orthogonal varimax rotation on the eight items of the ESS.

The initial solution was satisfactory [KMO = .806, χ 2(28) = 432.760, p = .000]. The communalities ranged from .45 to .64. From this initial solution, two factors were extracted with eigenvalues greater than 1 according to the Kaiser and Guttman rule (eigenvalue: 3.194 and 1.418), explaining 57.65 % of scale variance (Fig. 1).

Table 3 displays the component matrix loadings for each item (>30) after varimax rotation for a two-factor solution.

As shown in Table 3, there are three items of the ESS that loads on both factors. Furthermore, the data from the component transformation matrix also suggests interrelation between the two extracted factors (see Table 4).

Given the issues raised with a two-factor solution, another exploratory principal component analysis was performed with a forced one-factor solution. The results revealed that commonalities ranged from .27 to .55 with a single factor model. The total variance explained by this solution was 39.92 %. As shown in Table 5, all items have higher loadings (>.50) within a single factor. This unidimensional solution is suitable to describe our data since it is appropriate to describe the construct and the underlying factor structure.

Internal validity

To study the internal validity of the ESS, item-total correlations with r Pearson were performed. The results show moderate to strong positive correlations (.46 < r > .73) between each individual item and the total scale (all p levels = .000). Item 6 and item 8 are the ones that have the lowest correlation with the total scale.

Criterion-related validity

The criterion-related validity of the ESS was tested with an independent t test that was performed to compare patients diagnosed with OSA vs. healthy participants in ESS scores. Table 6 depicts mean scores and standard deviations of the ESS total score in OSA patients and healthy participants.

The results presented in Table 6 indicate that subjects diagnosed with OSA have higher levels of sleepiness compared to healthy participants [t(220) = −2.234, p = .026].

Reliability

The internal consistency was estimated using Cronbach’s alpha method that was performed to study the reliability of the ESS in evaluating sleeping disturbances. The Cronbach’s alpha (.77) was acceptable for the version of the ESS with the original eight items, even after the possibility of increasing the alpha level when items were removed was studied. The average inter-item correlation was r = .31 (.05 < r > .47), in which item 6 and item 8 were the most problematic items according to this analysis.

Rasch model

In line with the recommendations of Linacre [41], the category effectiveness of rating scale was tested with a four-category system. The item polarity in the actual scale shows a range from .43 to .72, in which all items are aligned in the same direction in the latent variable (Table 7).

The category statistics is shown in Table 8. The results for categories are consistent with the guidelines of Linacre [41], indicating the following: at least 10 observations for each category; an unimodal distribution (peak at category 0 and a negative skew to category 3); the average measure advances monotonically with category, with an increase from .89 to 1.55 logit between consecutive categories; the Outfit mean-square values of the four categories are around 1.0 logit, all categories are less than 2.0 logit, suggesting a reasonably uniform level of randomness in the data; the step calibration advances about .69 to .79 per step, suggesting that people with higher levels of sleepiness are more prone to choose higher categories, which were modal along the variable.

As shown in Fig. 2, each category has a real probability of being selected by the sample; the relationship between measure and ratings for each category is considered adequate; the small and large advancements of steps’ difficulties between consecutive categories show about 1.2 to 1.6 logit. Overall, these results suggest that all the guidelines of Linacre have been satisfied.

The principal component analysis of residuals from the RM indicates that the assumption of unidimensionality is empirically corroborated given that the analysis of residuals explains no more than 10 % of the variance (exact value was of 9.2 %) and the percentage of variance explained by the RM is over 20 % (exact value of 61 %).

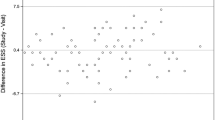

The score statistics is presented in Table 8. Model fit is adequate: no item outfit is over 2 (severe misfit), the percentage of people with outfit over 2 is small, and average outfit values, for items and people, are close to 1 (perfect fit). Furthermore, the score reliability through Item Separation Reliability value (.99), Person Separation Reliability value (.85), and Cronbach’s alpha (.78) was considered high.

The item-person map is depicted in Fig. 3, which shows the “ability” of the people and “difficulty” of the items on the same pathway. A visual inspection of Fig. 3 suggests that item 6 (sitting and talking to someone), item 8 (in a car, while stopped for a few minutes in traffic), and item 3 (sitting inactive in a public place; e.g., a theater or meeting) are those considered as more difficult according to these results. On the other hand, item 2 (watching television) and item 5 (lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances allow it) are the less difficult items according to RM.

Discussion

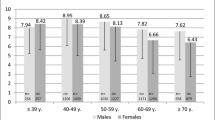

In order to increase variability and to prevent floor effects, the statistical analysis was performed for the total sample, including both healthy participants and patients with OSA. However, it is worth noting that the proportion of gender is different between OSA and healthy participants. In this regard, one normative study using the ESS [43] does not show any effect of gender on the ESS total score, although there is evidence [44] for an impact of respiratory sleep disorders on daytime sleepiness, especially under the age of 40. This becomes, however, much less likely for the overall sample, in which the main statistical procedures were carried out.

Item analysis showed that item 6 and item 8 have relevant deviations from normal distribution (as regard to kurtosis, skewness, and range of values, especially in item 6). In our view, this result may describe a floor effect which is often observed in healthy individuals [13], but it is also possible that these items are those that are most affected by social desirability. One possible explanation for this is that situations as described in item 6 (during a conversation with another person) and item 8 (driving a car) are difficult to assume as possible situations where one can fall asleep compared to other contexts in which attention is not socially expected.

The structural validity, evaluated through a principal component factor analysis, initially showed two strongly interdependent factors. However, a forced factor analysis shows an interpretable unidimensional structure, with item loadings (.52 to .74) close to those found in a clinical sample with the original version from English language [28]. The analysis of the item-total correlations supports the internal validity of the scale, with exception for item 6 and item 8. These results are also consistent with a previous data, despite being more similar to clinical than the control samples of Bloch and colleagues [13].

The comparisons of the ESS total score among patients diagnosed with OSA and healthy participants reveal adequate criterion validity. It is important to consider that the scores found in our study are lower than those reported for the original version [28], either for patients with OSA or healthy subjects, being more adjusted to other versions of the ESS found in the literature [9, 13, 27].

One important issue with previous research on this topic is that most studies include convenience samples of college students as controls that are younger than most of the patients with OSA. In these versions [9, 13], the mean age of the control group is higher (about 10 years higher), being more similar to our control sample. Another important confounder in these samples of college students is that the need for sleep may vary depending on the time of school year. During exam periods, students have less sleeping hours, which may increase the propensity to fall asleep during some of the situations described in these measures.

The internal consistency of the total scale, estimated through the Cronbach’s alpha, suggests minimal adequacy of the scale according to Nunnaly [45]. In addition, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient found in our study is in the range of values found for clinical and control samples [9, 11, 13, 18, 20, 22, 27].

The RM analysis suggests that the standard version of the scale with four-category system is consistent with the guidelines [41], and the data fit the Rasch model fairly well. Consistent with previous reports [32, 33], no items with high misfit were found through the RM, which also supported the unidimensionality of the ESS.

Overall results from the CMT and RM showed adequate structural, internal, and criterion-related validity of the ESS, and reliability as well, suggesting this as a useful and effective measure for assessing sleepiness in Portuguese adults.

References

Johns M (1991) A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 14:540–545

Johns M (1994) Sleepiness in different situations measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 17:703–710

Johns M (1998) Rethinking the assessment of sleepiness. Sleep Med Rev 2:3–15

Johns M (2000) Sensitivity and specificity of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), the maintenance of wakefulness test and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale: failure of the MSLT as a gold standard. J Sleep Res 9:5–11

Johns M (1993) Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Chest 103:30–36

Furuta I, Kaneda R, Kosaka K et al (1999) Epworth Sleepiness Scale and sleep studies in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 51:301–302

Silva GE, Vana KD, Goodwin JL, Sherill DL, Quan SF (2011) Identification of patients with sleep disordered breathing: comparing the four-variable screening tool, STOP, STOP-bang, and Epworth Sleepiness Scales. J Clin Sleep Med 7:467–472

Aloé F, Pedro A, Tavares SM (1997) Epworth Sleepiness Scale outcome in 616 Brazilian medical students. [Article in Portuguese]. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 55:220–226

Bertolazi AN, Fagondes SCH, Hoff LS et al (2009) Portuguese-language version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale: validation for use in Brazil. [Article in Portuguese]. J Bras Pneumol 35:877–833

Chung KF (2000) Use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in Chinese patients with obstructive sleep apnea and normal hospital employees. J Psychosom Res 49:367–372

Chen N-H, Johns MD, Li H-W et al (2002) Validation of a Chinese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Qual Life Res 11:817–821

Kaminska M, Jobin V, Mayer P et al (2010) The Epworth Sleepiness Scale: self -administration versus administration by the physician, and validation of a French version. Can Respir J 17:e23–e34

Bloch KE, Schoch OD, Zhang JN, Russi EW (1999) German version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Respiration 66:440–447

Sauter C, Popp R, Danher-Hopfe H et al (2007) Normative values of German Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Somnolgie 11:272–278

Tsara V, Serasli E, Amfilochiou A, Constantinidis T, Christaki P (2004) Greek version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Breathing 8:91–95

Vignatelli L, Plazzi G, Barbato A et al (2003) Italian version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale: external validity. Neurol Sci 23:295–300

Takegami M, Suzukamo Y, Wakita T et al (2009) Development of a Japanese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (JESS) based on item response theory. Sleep Med 5:556–565

Cho YW, Lee JH, Son HK et al (2011) The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Breathing 15:377–384

Gander PHH, Marshall NS, Harris R, Reid P (2005) The Epworth Sleepiness Scale: influence of age, ethnicity, and socioeconomic deprivation. Epworth Sleepiness Scores of adults in New Zealand. Sleep 28:249–253

Beiske KK, Kjelsberg FN, Ruud EA, Stavem K (2009) Reliability and validity of a Norwegian version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Breathing 13:65–72

Sanford SD, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH et al (2006) The influence of age, gender, ethnicity, and insomnia on Epworth Sleepiness Scores: a normative US population. Sleep Med 7:319–326

Rosales-Mayor E, Castro JR, Huaynay L, Zagaceta K (2012) Validation and modification of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in Peruvian population. Sleep Breathing 16:59–69

Kopitovic I, Trajanovic N, Prodic S et al (2011) The Serbian version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Breathing 15:775–780

Chiner E, Arriero JM, Signes-Costa J, Marco J, Fuentes I (1999) Validation of the Spanish version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in patients with a sleep apnea syndrome [article in Spanish]. Arch Bronconeumol 35:422–427

Banhiran W, Assanasen P, Nopmaneejumruslers C, Metheetrairut C (2011) Epworth Sleepiness Scale in obstructive sleep disordered breathing: the reliability and validity of the Thai version. Sleep Breathing 15:571–577

Izci B, Ardic S, Firat H et al (2008) Reliability and validity studies of the Turkish version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Breathing 12:161–168

Jiménez-Correa U, Haro R, Poblano A et al (2009) Mexican version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Open Sleep J 2:6–10

Johns M (1992) Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep 15:376–381

Knutson KL, Rathouz PJ, Yan LL, Liu K, Lauderdale D (2006) Stability of the Pittsburgh sleep quality index and the Epworth sleepiness questionnaires over 1 year in early middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Sleep 11:1503–1506

Miletin MS, Hanly PJ (2003) Measurement properties of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep Med 4:195–201

Smith SS, Oei TP, Douglas JA et al (2008) Confirmatory factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 9:739–744

Martinez D, Breitenbach TC, Lumertz MS et al (2011) Repeating administration of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale in clinical useful. Sleep Breathing 15:763–773

Ulander M, Arested K, Svanborg E, Johansson B, Broström A (2012) The fairness of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale: two approaches to differential item functioning. Sleep Breathing 17:157–165

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Knol DL et al (2010) The COSMIN checklist for evaluating the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties: a clarification of its content. BMC Med Res Methodol 10:22

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick LD et al (2010) The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res 19:539–549

Andrich D (1988) Rasch models for measurement. Sage, London

Wright BD, Mok M (2004) An overview of the family of Rasch measurement models. In: Smith EV, Smith RM (eds) Introduction to Rasch measurement. JAM Press, Maple Grove

Prieto G, Delgado AR, Perea MV, Ladera V (2010) Scoring neuropsychological tests using the Rasch model: an illustrative example with the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure. Clin Neuropsychol 24:45–56

Wilson M (2005) Constructing measures. LEA, Mahwah

Bond TG, Fox CM (2007) Applying the Rasch model, 2ªth edn. LEA, Mahwah

Linacre JM (2002) Optimizing rating scale category effectiveness. J Appl Meas 3:85–106

Linacre JM (2013) A user’s guide to Winsteps Ministep—Rasch-model computer programs. Winsteps.com, Chicago

Sanford SD, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH et al (2011) The influence of age, gender, ethnicity, and insomnia on Epworth Sleepiness Scores: a normative US population. Sleep Med 7:319–326

Morrell MJ, Finn L, McMillan A, Peppard P (2012) The impact of ageing and sex on the association between sleepiness and sleep disordered breathing. Eur Respir J 40:386–393

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, USA

Conflict of interest

None, for all authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sargento, P., Perea, V., Ladera, V. et al. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale in Portuguese adults: from classical measurement theory to Rasch model analysis. Sleep Breath 19, 693–701 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-014-1078-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-014-1078-6