Abstract

Foundations are often criticized as organizations of elite power facing little accountability within their own countries. Simultaneously, foundations are transnational actors that send money to, and exert influence on, foreign countries. We argue that critiques of foundation power should expand to include considerations of national sovereignty. Recently, countries across the globe have introduced efforts to restrict foreign aid, wary of the foreign influences that accompany it. However, it is unknown whether these restrictions impact foundation activity. With data on all grants from US-based foundations to NGOs based in foreign countries between 2000 and 2012, we use a difference-in-difference statistical design to assess whether restrictive laws decrease foundation activity. Our results suggest that restrictive laws rarely have a significant negative effect on the number of grants, dollars, funders, and human rights funding to a country. These results call for attention to considerations of foundation accountability in a transnational context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Philanthropic foundations are experiencing a new wave of contestation. Activists, leaders, and scholars are examining how to hold foundations accountable to their local communities, to democratic norms of fairness and equality, and to social justice goals (Anheier and Leat 2013; Kohl-Arenas 2015; McGinnis Johnson 2016; Reich 2018). However, foundations are also increasingly self-identifying and acting as global citizens (McGoey 2015; Ravishankar et al. 2009; Rey-Garcia and Puig-Raposo 2013). As a result, foundations not only impact the governance of the nation in which they are legally based, but also influence the governance of each country where they provide grants (Heydemann and Kinsey 2010; Benjamin and Quigley 2010). Despite our increasingly globalized world, questions regarding foundation power and accountability have typically been asked within a domestic context, focusing on the country in which a given foundation is headquartered.

Simultaneously, foreign countries are increasingly attempting to curb foundation activity from abroad, in an attempt to assert their own sovereignty. Many governments have recently passed laws that constrain how NGOs within their country can receive foreign funds, commonly known as “restrictive laws” (Dupuy et al. 2016; Rutzen 2015). These measures include administrative and legal obstacles, propaganda against NGOs that accept foreign funding, harassment or expulsion of external aid groups offering civil society support, and outright bans of certain types of funding (Ibrahim 2015). Though each law has its own complexity, restrictive laws represent attempts to assert sovereignty by impeding or blocking foreign funding for civil society groups (Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014). More than 50 countries have recently enacted or seriously considered restrictions on the ability of local NGOs to form and operate with the support of foreign funds. These range from Russia’s foreign agents’ laws, to Ethiopia’s clampdown on human rights organizations supported by foreign aid, to Sri Lanka’s decision to require all NGOs that receive foreign funding to register with the Ministry of Defense (Breen 2015).

Efforts to defend sovereignty, particularly on the part of less-powerful states, are admirable endeavors. Similarly, the efforts of private foundations to advocate for global solutions to environmental degradation and transnational efforts supporting human rights can also be crucial components of creating a more sustainable and equitable world. The challenge is when these two aims overlap: increasingly assertive national sovereignty confronts increasingly transnational philanthropic goals. Given this complex empirical reality, we argue that research about foundation power and accountability would benefit from examining foundations as significant transnational actors, moving money, services, and values around the globe (Heydemann and Kinsey 2010). This requires moving beyond a focus on accountability to the governments within the foundation’s host country. This paper studies the case of restrictive laws as an effort by foreign countries to assert sovereignty against elite philanthropic foundations. Specifically, this paper asks, do restrictive laws significantly decrease US foundation activity to a country?

Prior research has shown that state donors are responsive to countries’ restrictive laws, reducing international aid dollars after the passage of a restrictive law (Dupuy and Prakash 2018). We complement this research by investigating whether the laws are effective in decreasing the private foreign funding of US grantmaking foundations. We focus on international funding from private foundations headquartered in the United States. The US philanthropic sector is of particular concern because of its relative largesse, its global supremacy, and its leadership role in global aid (Christensen and Weinstein 2013; Longhofer and Schofer 2010). We analyze whether restrictive laws passed between 2002 and 2010 have significantly decreased the number of US foundation grants, dollars, organizations, or human rights funding to a country. In the literature review that follows, we first present research on Westphalian sovereignty that hypothesizes that restrictive laws will restrict US foundation activity to a country. We follow this section with research on US philanthropy which poses an alternative hypothesis, that restrictive laws will not influence US foundation activity to a country. After presenting our methods and findings we offer a discussion for what these results mean for national sovereignty and the power of transnational philanthropy.

Restrictive Laws: Attempts to Defend Sovereignty Through Limiting Foreign Funding

States are defined by their ability to preserve, maintain, and regulate their territorial boundaries, thus the notion of soveriegnty is critical to any country's existence (Tilly 1990; Andreas 2003). However, sovereignty is not a straightforward concept. Sovereignty is simultaneously a normative condition, a practice, an empirical reality, and a utopian inspiration. Our focus in this paper is on Westphalian sovereignty. In this concept, each nation state has sovereignty over its territory and domestic affairs, to the exclusion of all external powers, on the principle of non-interference in another country’s domestic affairs (Krasner 1999). This long-held principle of non-intervention was articulated by the German philosopher Christian Wolff (1934[1764], pg. 131):

To interfere in the government of another, in whatever way indeed that may be done, is opposed to the natural liberty of nations, by virtue of which one nation is altogether independent of the will of other nations in its actions. […] If any such things are done, they are done without right. And although the less powerful may be compelled to yield at length to the more powerful, nevertheless, might confers no right which the latter does have from any other source.

This conceptualization of sovereignty generally assumes that each state—regardless of size or resources—is equal under international norms. Westphalian sovereignty, therefore, is premised upon the reality of unequal power among nations, and theoretically attempts to provide a protection for weaker states. Thus, weaker states have always been the strongest supporters of this rule of non-intervention, amidst a backdrop of imperialism and colonialism (Arnove 1980; Sen 1999).

The principles of Westphalian sovereignty hold for the receiving state regardless of the intentions of the intervening state. As a result, the soft power exerted by well-intentioned, benevolent institutions can also be met with skepticism (Easterly 2006). For example, foundations may have good intentions in their philanthropic endeavors, but their disregard of Westphalian sovereignty can be complicit in resurrecting colonial impulses to modernize, influence, and control foreign populations (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1999; McGoey 2015). At the same time, some governments fear the political instability a foreign-funded civil sector might create. This latter rationale garners more critique from outside observers, who perceive nation states as tamping down on democracy and human rights (Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014).

In recent decades countries around the world have asserted their sovereign rights by introducing “restrictive laws” that limit foreign funding and foreign NGOs from operating within their country (Howell et al. 2008). While the mainstream discourse in the United States has featured strong condemnation for these laws, many other Western, democratic governments have adopted them as well, underscoring that this is not simply a matter of autocratic, predatory government control (Rutzen 2015). In fact, since 1999, more than 50 countries representing every region of the world have passed laws constraining the ability of domestic NGOs to receive foreign funds (CIVICUS Monitor 2019; Dupuy et al. 2016; Rutzen 2015). These countries span the globe: from Canada to Cameroon, Israel to Indonesia, and Bolivia to Belarus. (Countries that passed restrictive laws between 1999 and 2012 are illustrated in Fig. 1 and listed in Table 1.)

These laws are diverse. For the purpose of this paper we focus on laws that place constraints on foreign funding of NGOs either through: (1) requiring costly reporting requirements on NGOs that receive foreign funding, and/or (2) directly limiting what foreign funds can be spent on and how foreign funds can enter the country (Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014; Dupuy and Prakash 2018). The distinction between these two avenues for restriction is whether the constraints and costs are placed on the NGO or on the transaction. This boundary is often blurred—for example, a part of Egypt’s and Uzbekistan’s laws require NGOs to apply for government approval before they can receive a foreign grant (Rutzen 2015). As a result of the diversity we do not seek to empirically differentiate between the two types of laws. Both serve to limit and control the discretion of foreign aid, whether it comes from governments, foundations, or public charities. They are efforts to constrain the power of foreign influence and make aid accountable to the governments of the recipient country. These regulations are a one-sided effort to restrict foreign influence in a nation’s civil society, and are often on the weaker end of a dyadic, power-imbalanced relationship.

Notably, while restrictive laws have been passed by countries spanning the economic spectrum, they are passed at differential rates depending on a country’s position within the global economic system. For example, as of 2012, nearly half (45%) of low-income countries, as defined by the World Bank,Footnote 1 had passed restrictive laws, while only about 10% of medium- and high-income countries had passed them. Middle- and high-income countries may have other recourses, such as greater influence within transnational governing bodies, and generally do not have the same strong dependency relationships based on foreign aid and economic reliance. Additionally, as noted above, Westphalian sovereignty is more consequential for weaker states. The lack of economic power of low-income countries leads them to adopt these laws at significantly higher rates (Dupuy et al. 2016).

These laws have been effective with respect to limiting bilateral and multilateral aid, particularly foreign funding from overseas governments to domestic NGOs (Christensen and Weinstein 2013; Dupuy and Prakash 2018).Footnote 2 This suggests that foundations might also reduce their funding to countries that pass these restrictive laws to observe and respect assertions of national sovereignty, or at the very least, to avoid the difficulties that might come with transgressing sovereign claims.

Hypothesis 1

Countries’ restrictive laws will decrease foundation activity toward NGOs in their country.

Philanthropy: Advancing Rights with Plutocratic Power

The norm of Westphalian sovereignty has been frequently challenged and violated by international donors advocating for human rights, environmental protection, and the maintenance of international stability (Krasner 1999). While many Western governments can and do regulate their philanthropic foundations' international activity, this regulation is often highly limited (Hayes 1996; Herzlinger 1996; Kramer 1981). In the United States, for example, foundations are a legally defined and regulated class of organizations, sharing a regulatory space with other tax-exempt charities, and must publicly list cursory information of all grants made (Hopkins and Blazek 2014). Additionally, for international grantmaking, a foundation may have to engage in paperwork to identify “equivalency determination” for the grantee organization, an IRS regulation to determine whether foreign NGOs are “equivalent” to US public charities (Reis and Warren 2016). Outside of these administrative stipulations, US foundations are free to pursue grantmaking activities overseas irrespective of any host country's regulatory infrastructure.

Many private foundations have identified countries’ assertions of sovereignty as counterproductive in several ways (Aksartova 2009). First, philanthropists often challenge sovereignty when they view foreign societies as undermining dominant norms of justice and equality (Benjamin and Quigley 2010). Second, some ecological analysts see state sovereignty as potentially antithetical to the prerequisites for ecological security and long-range human survival (Misch 1989). Lastly, when funds are used to build self-sustaining civic infrastructures, foundation monies can be used to support state capacity thereby strengthening a country’s legitimacy and longer-term sovereignty (Brass 2016). At the time of the grant, these efforts undermine Westphalian sovereignty, but advocates argue that they are in service of an underdog—advancing human rights—or for the longer-term benefits of the country. Viewed from these perspectives, we may anticipate that US-based foundations will be less sensitive to notions of Westphalian sovereignty and, as a result, will not be influenced by countries’ restrictive laws.

Governments have been found to be more responsive to restrictive laws (Christensen and Weinstein 2013; Dupuy and Prakash 2018). Perhaps this is because they engage in multiplex ties with other countries, while also adhering to the normative concerns of national sovereignty, accountability, and foreign influence (Longhofer and Schofer 2010; Meyer et al. 1997). In contrast, while foundations are also transnational actors subject to similar world society norms, they generally have more decentralized relationships with other countries, because they rarely act collectively as a uniform single, actor (von Schnurbein 2010). Additionally, despite the fact that the effects of foreign foundation funding can be wide-ranging and pervasive across a society (Meyer et al. 2020), the actions and decisions of a single foundation may appear far less significant than bilateral governmental actions. As a result, we might anticipate that foundations will be less sensitive to the same institutional norms as governments.

Furthermore, the powerful social position that foundations occupy may also enable them to ignore restrictive laws. Philanthropic foundations generally enjoy wide legitimacy from the public within their countries, as people trust that these organizations will work toward the common good (Drevs et al. 2014; Handy et al. 2010; Leviten-Reid 2012). However, elite philanthropists wield a concentrated and entrenched influence far beyond that of ordinary citizens (Saunders-Hastings 2018); they redirect tax money without an obligation to adjust to changing social conditions and public wishes (Goss 2016; Horvath and Powell 2016; Mosley and Galaskiewicz 2015). As private foundations require great wealth to found, those in control of even the most publicly-oriented foundations do not represent the concerns of the communities they fund (Callahan 2017; Goss 2016; Karl and Katz 1981; McGinnis Johnson 2016; Saunders-Hastings 2018). Furthermore, foundations generally have broad, amorphous, and ambiguous goals that can, and often do, easily facilitate the pursuit of unstated private, personal, or family-oriented goals (Gersick et al. 1990, 2004; Oelberger 2018). Applied to an international context, these critiques would lead us to expect US-based foundations may not respect the recent desires of foreign, public authorities.

Moreover, philanthropy is growing in influence and in objective numbers of grants, organizations, and dollars, with the rise of “disruptive” philanthropy, the prominence of donor-advised funds, and media coverage of high-profile living philanthropists (Anheier and Leat 2013; Goss 2016; Horvath and Powell 2016; IUPUI Lilly Family School of Philanthropy 2019; Madoff 2016; Rey-Garcia and Puig-Raposo 2013). Beyond simply disbursing funds, foundations actively and increasingly shape organizational fields, public consciousness, and governmental policy (Callahan 2017; Bartley 2007; Roelofs 2015; Tompkins-Stange, 2016). Through this process, foundations on all sides of the political spectrum often endorse the value of pluralism, arguing that the purpose, if not the necessity, of philanthropic work is its advocacy of minority and unpopular opinions (Anheier and Leat 2013; Reich 2018).

As a result of these multiple features, this private power has received critical attention from researchers, journalists, and even the foundation sector itself (Callahan 2017; Bernholz et al. 2016; Villanueva 2018), due to foundations' ability to shape public discourse, ideas, and values within a society (Aksartova 2009; Arnove 1980; Meyer et al. 2020). Altogether, given dominant philanthropic norms against Westphalian sovereignty and the relatively unchecked, comprehensive, and pervasive power of foundations, we may expect countries to be incapable of preventing foundations’ foreign influence (Meyer et al. 1997). This leads us to hypothesize an opposite outcome, thus:

Hypothesis 2

Countries’ restrictive laws will not decrease foundation activity toward NGOs in their country.

Data and Methods

We test these two competing hypotheses through a comprehensive dataset of US-based foundation grants to support work in foreign countries, paired with a dataset on when countries have introduced restrictive laws. We obtain the restrictive law data from 1999 to 2012 from several sources. We first retrieve a base dataset on low- and middle-income countries from Dupuy et al. (2016).Footnote 3 We augment this data with information on high-income countries from the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law’s Civic Freedom Monitor (ICNL 2019) and from CIVICUS’s reporting on civic openness (CIVICUS Monitor 2019), both of which track legal restrictions on NGOs, foreign funding, and civic freedoms.Footnote 4 Due to the variety of the laws it is difficult to capture the degree of restrictiveness of the written law or its actual implementation. We follow past scholars in operationalizing the passage of a restrictive law as a binary variable (Dupuy et al. 2016; Dupuy and Prakash 2018).

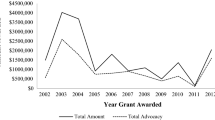

We obtained the grantmaking data from the Foundation Center, which manages a grants database containing records on all grants over $10,000 in size from US-based foundations, both private foundations and re-granting public charities.Footnote 5 Our dataset represents a subset of the Foundation Center database, covering all US foundation grants that are intended to support causes outside the United States for the period 2000 to 2012. The dataset consists of 161,688 unique grants.

We limit this dataset for the research question in several ways. First, we focus only on grants given to support work in a specific country, removing grants given to global efforts, such as climate change, and grants given to parts of the world with no national government (ex. the “Pacific Ocean”). Second, we remove all grants to countries that have passed restrictive laws outside of the years that our grantmaking data covers. This removes countries whose laws may have influenced foundation grantmaking activity in the time period under study but for whom we lack multiple data points either before or after the passage of their restrictive law (i.e., 1999–2001 and 2011–2012). We made this decision to ensure high fidelity data that can examine patterns of grantmaking to countries before and after passage of these laws. Altering these bounds to be more and less conservative does not change the results. Third, we do not include any data from the year the law was passed because the law may have taken effect in the middle of the year, confusing that year’s data, or may capture anticipatory foundation behavior. For countries that passed multiple laws, we only look at the years before the first law was passed and the years after the last law was passed, not including any of the years in between. Lastly, in line with our hypotheses, we only retain grants that were given to domestic NGOs—recipient organizations based in the same country as the grant’s intended beneficiaries. Our resulting dataset includes 2,777 grants given from 2000 to 2012, allocated by 158 foundations to 1,789 NGOs working in 124 countries, 21 of which passed restrictive laws between 2002 and 2010. Our unit of analysis is the country-year, that is, the foundation activity in a given country in a given year.

We classify countries as low-, medium-, and high-income based on the World Bank’s classification system (World Bank 2019). For countries that pass a restrictive law, we classify them according to their income category in the year they passed the law. For countries that do not pass a restrictive law, we classify them according to their classification in 2007, the middle point of our dataset.Footnote 6 We run separate models for each income level to see if the results change based on country income.

We also address variation in the location of the recipient NGOs that private foundations fund. Restrictive laws may effect foundation influence on a country, not just through domestic civil society but also through the intermediary of INGOs (non-domestic NGOs working inside the country of interest). Foundations may respond to restrictive laws by changing their activity regarding these third-party intermediaries. We run two additional subsets of our larger dataset testing the effects of restrictive laws on US-based foundation funding to (1) US-based NGOs, and (2) non-US and non-domestic NGOs intending to target beneficiaries in a given country.

Outcome Variables

We consider four different outcome variables, as it is unclear how the restrictive laws may influence US-based foundation funding: (1) the number of grants, (2) the dollar amount of all grants, (3) the number of foundations, and (4) the percent of grants to human rights causes.

Number of grants This is a count of the grants that US-based foundations gave to support programmatic work in a country. Foundations may lessen the number of grants because of restrictive laws due to more administrative difficulty and overhead and/or more programmatic uncertainty and risk in grant delivery. We calculate the log of the number of grants per year to account for skew.Footnote 7

Dollar amount of grants This is the sum of the dollar amount of all US-based foundation grants to work in a country in a year. The number of grants may be altered purely administratively, while the dollar amount may be a better measure of actual foreign influence and economic impact. We calculate the log of the total dollar amount to account for skew. The logged dollar amount has a correlation of 0.88 with the logged number of grants.

Number of foundations We count the number of unique foundations giving grants to programmatic work in a country in each year. Restrictive laws that make grant reporting and delivery more difficult may particularly impact foundations that lack the necessary administrative capacity. Alternatively, restrictive laws that target certain areas of funding may prevent a foundation that promotes, for example, religious activity, from being able to give grants in a country. The number of foundations has a correlation of 0.89 with the logged number of grants and 0.68 with logged dollar amount.

Human rights funding This is the percent of grants given for human rights work as determined by the initial dataset coded by the Foundation Center. This coding separates more political human and civil rights grants from more social services-oriented grants, such as health, education, environment, housing, and sanitation. We may expect restrictive laws to decrease the proportion of grants to human rights causes if the goal of the laws are to restrict civil liberties, dissidents, and political activism.Footnote 8 When there were no grants in a year to a country, we imputed the average human rights funding to that country over the full time period.Footnote 9 The percentage of human rights funding has an insignificant correlation with all of the other outcome variables.

Each of these outcome variables tests potentially different effects of these restrictive laws. Different results across outcomes may represent different ways restrictive laws may decrease foundation activity towards domestic NGOs.

Model

To assess whether the passage of a restrictive law has any impact on US-based foundation funding to a country we utilize a difference-in-difference causal inference statistical design. This design tests whether the magnitude of the change of a variable is different across time for countries that passed restrictive laws and those that did not. The design is robust to the fact that passage of a restrictive law is nonrandom and that there are unobserved factors correlated with both restrictive law passage and change in US-based foundation funding (Dupuy et al. 2016; Meyer 1995). The design accounts for the fact that US-based foundation funding might cause the passage of a restrictive law in the first place (Dupuy et al. 2016). This design does seek to establish causation, not mere correlation. However, establishing causation nearly always requires a set of assumptions. The key assumption of the difference-in-difference design is the parallel trends assumption (Meyer 1995). This assumes that any factor related to changes in foundation funding in countries that pass restrictive laws maintains a similar, average effect as in countries that do not pass restrictive laws. For example, we may expect GDP to correlate with both foundation funding and with restrictive law passage. But as long as the average expected effect of GDP on foundation funding is relatively similar in countries that do and do not pass restrictive laws, a much more conservative assumption, then our causal claims remain robust.

This model tries to detect whether the application of restrictive laws is associated with an altered trajectory of foundation grantmaking. For example, given that foundations are cumulatively increasing their number of grants internationally (IUPUI Lilly Family School of Philanthropy 2019), we might expect the number of grants to be rising across all countries regardless of restrictive law passage. The difference-in-difference model tests whether the rate of this increase is slower for countries that pass restrictive laws than countries that do not. We utilize the following difference-in-difference model for all four outcome variables:

where \(Y\) is one of the four outcome variables. \(\beta_{0}\) is the constant, the expected value of the outcome in the year 2000 for a country that never passes a restrictive law. \(\beta_{1}\) is the expected value of the outcome in the year 2000 for a country that will eventually pass a restrictive law between 2002 and 2010. A significant coefficient is a sign that restricting countries and non-restricting countries were significantly different in the given outcome before passage of the law. Restricting country is a binary variable that takes the value of one for any country that eventually passes a restrictive law in our time period, and a value of zero otherwise. \(\beta_{2}\) is the main coefficient of interest and shows the effect of a restrictive law on the outcome in question above and beyond the expected differences across country and across time. Law in effect is a binary variable that is a country-contingent interaction between restricting country and time. It takes the value of one in a country-year when a restrictive law has been previously passed, and zero otherwise. It always takes the value of zero for countries that never pass a restrictive law. We include necessary country fixed effects because we are interested in within country changes due to the passage of a restrictive law. Finally, we use year fixed effects to control for changes in the outcome over time. We used fixed effects instead of a continuous function to create a model that does not assume any overall time patterns.Footnote 10 This allows us to use the same model for all outcome variables that may vary differently over time. It also allows the model to better fit time trends over a time period that included multiple recessions and a highly dynamic global political economy.

The parallel trends assumption is a relatively weak assumption in causal inference and so we decide not to include other control variables in the analysis. In theory, we would like to control for variables that defy the parallel trends assumption, but we want to avoid including variables that may actually mask the difference restrictive laws can make. As there is little theory and evidence about what variables might violate this assumption, and we are already working with such few cases, we do not include any additional variables to preserve our degrees of freedom. We are interested in country income and relative NGO location, but we treat these variables as moderators, using them in separate models, not as controls that might break the parallel trends assumption. Given the variety of models we run, we hope to be able to build theories and assess future avenues of investigation from our preliminary findings.

Results

Do restrictive laws significantly decrease US foundation activity to a country? We analyze whether restrictive laws passed between 2002 and 2010 have significantly decreased the number of US foundation grants, dollars, organizations, or human rights funding to a country. Table 2 compares the descriptive differences in outcomes between countries that passed laws and those that did not. To create this table, we calculated non-restricting countries’ “before” values as their activity between 2000 and 2006, and their “after” values as their activity between 2007 and 2012. This break was when the average restrictive law was passed in other countries. This table shows that foundation activity in grants, dollars, and funders increased for all countries, whether they passed the laws or not. Foundations also gave less to human rights causes across all countries. However, we want to know if the restrictive law decreases funding activity to a country compared to the funding the country would have received if it had not passed a law. Our model tells us if restricting countries saw a significantly lower increase in funding activity than countries that did not pass restrictive laws.

Table 3 displays the difference-in-difference model results for foundation funding of domestic NGOs. Table 3 shows mixed support for Hypothesis 2—that foundation activity will not be impacted by restrictive laws. Where it does not support Hypothesis 2, Table 3 actually suggests that the passage of restrictive laws significantly increases the number of grants and funders to a country. The number of dollars and percentage of human rights funding are insignificantly effected by restrictive laws. These results refute Hypothesis 1.

These findings may be contingent on the income of the country. Both sovereignty and relative foundation power are impacted by relative wealth. Table 4 features separate models for low- and middle-income countries (there were no domestic grants to high-income countries that passed the law during the time period under study). The results for low-income countries shows that there are no significant effects of restrictive laws on the outcome variables. This provides further support for Hypothesis 2. The results for middle-income countries also strongly refute Hypothesis 1 and mimic the results from Table 3, suggesting that restrictive laws actually significantly increase the number of grants and funders given to a country.

The results regarding foundations’ direct relationships with domestic NGOs fully reject Hypothesis 1. However, do these laws effect foundation funding of INGO intermediaries? Tables 5 and 6 display the results for the funding of US-based NGOs and Tables 7 and 8 display the results for non-domestic NGOs based outside of the USA. Tables 5 and 7 are the results of all countries grouped together, while Tables 6 and 8 are separated by income.

Table 5 exactly replicates the results of Table 3 in the effect of the restrictive laws. Middle-income results in Table 6 also replicate those in Table 4. However, the result for low-income countries in Table 6 is different from the domestic NGO results in Table 4. As Hypothesis 1 predicts, the dollars flowing to low-income countries through US-based NGOs does decrease significantly. However, all other measures are insignificant. The high-income results in Table 6 dispute Hypothesis 1, showing restrictive laws significantly increase the number of grants and amount of dollars flowing to the country, while all other measures are insignificant.Footnote 11 Table 6 shows country income is a crucial moderator of restrictive law effects on US-based NGO funding.

Table 7 continues to provide broad support for Hypothesis 2 regarding non-domestic, non-US-based NGOs. Restrictive laws do significantly decrease funding for human rights causes to these NGOs. However, this result is only marginally significant and is not shown in Table 8 implying the effect is due to a relatively smaller decrease in human rights funding through these NGOs to high-income countries. All other variables are insignificant. When we run separate models by income in Table 8, we see more support for Hypothesis 1. For low-income countries, US-based foundation activity significantly decreases regarding non-US, non-domestic intermediaries. The number of grants, funders, and dollars all decrease significantly, creating broad support for Hypothesis 1, although human rights funding is insignificant. However, these results are relatively marginal and do not stand up to all sensitivity tests. Middle-income results show no significance, continuing to support Hypothesis 2. The results for the number of grants and funders are no longer significantly positive as they were for US-based and domestic NGOs. There are no results for high-income countries because the high-income countries that passed restrictive laws in this time period were only given grants through US-based NGOs.

Discussion

Our paper substantiates that US foundations are private, powerful, and relatively unrestricted. We set out to examine whether the recent attempts by dozens of countries around the world to restrict foreign funding have been successful, particularly in limiting US-based foundations' grantmaking to low-income countries, which have few other recourses to assert their sovereignty. Testing the most comprehensive dataset to date, we find that countries’ restrictive laws are predominantly unsuccessful in restricting funding from US-based foundations. The one area in which we did find that foundations decreased their giving after the passage of a restrictive law was with respect to non-domestic NGOs, those working in, but not based within, low-income countries. In all other cases, the results show that foundations undergo no significant change or may actually increase their grantmaking activity after the passage of restrictive laws. Though these results do not conclusively prove that restrictive laws have no effect, the null results are illuminating alongside other scholars' clear findings related to the impact of restrictive laws on bilateral governmental aid (Dupuy and Prakash 2018). It appears that US-based foundations’ grantmaking to domestic countries’ civil society is relatively immune to countries’ attempts to limit this funding. In many cases, US-based foundations seem to actively flout restrictive laws, with more funders and grants flowing to countries after they have passed a restrictive law. However, the amount of money flowing to a country only rarely increases as a result of a law’s passage, meaning that often a country is receiving more, but smaller, grants than countries that did not pass a restrictive law.

The lone, albeit precarious, support of Hypothesis 1—the funding of non-domestic NGOs doing work in low-income countries—deserves more comment. Research shows that NGOs adjust their behavior as a result of restrictive laws (Agati 2007; Crotty et al. 2014), and international NGOs might cut programs, staffing, and offices in countries that pass these laws. These cuts might predominantly focus on low-income countries where the INGOs might be more visible. Our results regarding non-domestic NGOs may result from foundations responding to this lessened demand for funds on the part of the INGO, rather than a self-conscious response to the restrictive law. Alternatively, this finding could be the result of an intentional foundation strategy to appease the foreign governments of low-income countries. Domestic grants could be intentionally diverted to more government-fostered NGOs, while removing funding from INGOs that may be more difficult for these countries' goverments to control (Moder and Pranzl 2019).

The broader results in support of Hypothesis 2 are the central finding—foundations’ activity is not altered by a country’s restrictive laws. To some, this is likely welcome news. Foreign aid restrictions have shocked and worried many rights’ advocates (Carnegie and Marinov 2017). Observers of democracy suggest that a pluralist and diverse civil sector is critical to maintaining a humanitarian and democratic polity and government (Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014). Simultaneously, environmental activists have encouraged a more transnational approach to addressing our climate crisis and argued that national sovereignty can undermine necessary efforts (Misch 1989). The evidence presented here shows that these worries, insofar as they concern US-based foundation grantmaking decisions, may be unfounded. Even amidst restrictive laws, foundations remain active participants in funding and supporting domestic civil society.

Other observers may find these results more worrisome. US-based foundations have historically been bearers of imperialist ideas (Aksartova 2009; Arnove 1980). Their power is relatively unchecked and their potential to negatively influence cultures and communities across the world has been documented to bring about both welcome and positive change, as well as deleterious consequences for individuals, communities, and governments. Acknowledging that attempts to assert self-determination are ignored by a philanthropic elite can be sobering.

As scholars, we do not argue a particular normative position within this debate. What we do argue is that these results demand more questioning and theorizing about the role of US-based foundations on the global stage. When and with what norms of sovereignty should foundations engage in transnational work? How might foundations be more accountable to certain actors outside of their home country? Where can and should foundation power be limited and how? We hope that the conceptual and empirical work in this paper helps to inform and move this scholarly conversation forward.

Limitations and Future Work

This research has several limitations, mostly stemming from the limited grantmaking dataset which restricted our examination to laws passed from 2002–2010. This captures a bulk of the laws passed in the world but omits multiple cases. From this data, we cannot know if these laws take a longer period of time to show strong effects. With the analyses we did run, however, we found no evidence that laws become more effective over time, or that they have delayed impacts.Footnote 12 Additionally, the laws’ impact on bilateral aid was relatively immediate, and we have no reason to believe the impact on US foundations would be delayed.

A second limitation is that our data did not capture the passage of laws from many high-income countries. Through the present, high-income countries have passed restrictive laws at similar rates to middle-income countries, but our snapshot was not able to capture many high-income country restrictive laws, most of which became law after 2010. The ones that were captured, Qatar and Bahrain, should probably not be taken as indicative of larger trends among high-income countries. High-income countries may be a special case, where the power dynamics between US foundations and domestic civil society are quite different, and would require further data to accurately measure (Arnove 1980; Ivanova and Neumayr 2017).

Our use of a blunt, binary indicator of restrictive law passage is another limitation. In attempting to add more nuance to this measure we faced the same difficulties as other scholars to accurately operationalize and contextualize each specific and complex law. A more nuanced measure may show which types of laws may significantly reduce US foundation funding but given our findings, any effect is likely to be relatively minor. Our findings do show at the very least that, on average, these laws do not significantly reduce foundation activity. Similarly, there may be missing crucial explanatory variables beyond the NGO location and country income. However, there is no theory or evidence of what these might be, and we have no reason to believe the parallel trends assumption does not hold. While a key variable may tell a more complex story of causation, our findings still show that, on average, foundation activity toward domestic NGOs is not significantly reduced after the passage of these laws.

We encourage future research to complement this study with an investigation into more qualitative changes that may have resulted from the passage of restrictive laws. Qualitative data could assess the efficacy of these restrictive laws on the potential changes that US foundations or their recipient NGOs might undertake.Footnote 13 Qualitative data could also assess whether and how foundations acknowledge, interpret, and act upon these laws. For instance, foundations may have been significantly impacted by the restrictive laws but may also have worked to fill the void left by the reduction in bilateral aid. These two forces may cancel out in the quantitative aspects of foundation activity measured here. Qualitative data could also assess changes in actual foundation influence in a country. Dollars and grants do not necessarily equate to a specific amount of influence or the direction of that influence. Restrictive laws may not be successful in limiting foundation activity, but may be successful in their ultimate goal of restricting foreign influence.

Finally, as wealth grows across the world and elite philanthropy is replicated in many aid-recipient countries, it becomes increasingly necessary to ask further questions regarding philanthropic power and transnational accountability (Callahan 2017; Future Agenda 2018). We encourage future scholarship to examine whether the null effects we find are replicated when examining philanthropy originating from other countries. Doing so will assist in theorizing what foundation accountability means outside of democracies and in foreign nations. Future work could begin to answer and consider many of these questions from a variety of philosophical and empirical perspectives.

Conclusion

While questions about national government sovereignty and transnational foundation power have been relevant since the first foundations began their work, they have become increasingly timely and crucial as foundations undertake more grantmaking in a globalizing and interconnected aid system. In part, these influences have spurred countries to assert their sovereignty in restricting foundations’ influence, but we have not fully understood the extent of power that these countries actually hold. Identifying the limited effect of these attempts with respect to US transnational philanthropy will hopefully assist in developing a more robust conceptual and empirical understanding of the tensions between national sovereignty and transnational philanthropy.

Notes

We understand that this is not an ideal classification system but allows for direct comparisons to similar studies (ex. Dupuy et al. 2016).

This is not a simple cause and effect. Dupuy et al. (2016) try to predict passage of restrictive laws in low- and middle-income countries and find that the amount of development aid received in an election year is positively related to the passage of restrictive laws.

This is the same dataset used by Dupuy and Prakash (2018) that showed significant decreases in bilateral and multilateral aid.

We run separate models by country income to address any potential differences in coding and identification from Dupuy et al. (2016).

While our theoretical section focuses more on private foundations than public charities, we are unaware of any restrictive law that differentiates between the two. We include public charities because the concerns regarding foundation power frequently extend to re-granting public charities (Grønbjerg 2006), donor-advised funds at public charities are a crucial part of private, elite philanthropy (Madoff 2016), and re-granting public charities have an increasingly relevant role in global philanthropy (Gunther 2017). We run a sensitivity analysis excluding public charities from the dataset and receive identical results.

Changing the year we use to assign income classification, for both restricting countries and non-restricting countries, does not change results.

When grants and dollars are not transformed, the coefficients lose precision and significance.

We tested the rates of funding toward other issue areas and received consistent, insignificant results.

Alternative imputation procedures, and removing country-years with no data, do not change results.

Modeling time as different polynomial functions did not change results.

We do not spend much time analyzing this result. Due to Qatar and Bahrain’s geographic, historical, and governmental similarities, as well as the commonality that they received no foundation grants prior to the passage of their law, we hesitate to over interpret the significant finding in this model.

A sensitivity analysis checking for potential lagged effects saw increasingly weak effects over time. The laws seem to have their largest effects immediately.

While our dataset had more detailed information on foundation grants, such few grants went to each country each year that attempts to analyze characteristics of foundations were characterized by high variation and insignificant findings. We do lack crucial information on recipient domestic NGOs in our data, but NGO traits are also likely to see high variation in our models. Qualitative data could be valuable to understand the impact of these laws on different NGO- and foundation-level traits.

References

Agati, M. (2007). Undermining standards of good governance: Egypt’s NGO law and its impact on the transparency and accountability of CSOs. International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law, 9, 56–75.

Aksartova, S. (2009). Promoting civil society or diffusing NGOs? U.S. donors in the former Soviet Union. In D. C. Hammack & S. Heydemann (Eds.), Globalization, philanthropy, and civil society: Projecting institutional logics abroad. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Andreas, P. (2003). Redrawing the line: Borders and security in the twenty-first century. International Security, 28, 78–111.

Anheier, H. K., & Leat, D. (2013). Philanthropic foundations: What rationales? Social Research: An International Quarterly, 80, 449–472.

Arnove, R. F. (Ed.). (1980). Philanthropy and cultural imperialism: The foundations at home and abroad. Boston: G. K. Hall.

Bartley, T. (2007). How foundations shape social movements: The construction of an organizational field and the rise of forest certification. Social Problems, 54, 229–255.

Benjamin, L. M., & Quigley, K. F. F. (2010). For the world’s sake: U.S. foundations and international grantmaking. In H. K. Anheier & D. C. Hammack (Eds.), American foundations: Roles and contributions (pp. 1990–2002). Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Bernholz, L., Cordelli, C., & Reich, R. (2016). Introduction: Philanthropy in democratic societies. In R. Reich, C. Cordelli, & L. Bernholz (Eds.), Philanthropy in democratic societies: History, institutions, values. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1999). On the cunning of imperialist reason. Theory, Culture & Society, 16, 41–58.

Brass, J. N. (2016). Allies or adversaries: NGOs and the State in Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Breen, O. B. (2015). Allies or adversaries: Foundation responses to government policing of cross-border charity. International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law, 17, 45–71.

Callahan, D. (2017). The givers: Wealth, power and philanthropy in a new gilded age. New York: Penguin.

Carnegie, A., & Marinov, N. (2017). Foreign aid, human rights, and democracy promotion: Evidence from a natural experiment. American Journal of Political Science, 61, 671–683.

Carothers, T., & Brechenmacher, S. (2014). Closing space: Democracy and human rights support under fire. Washington: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Christensen, D., & Weinstein, J. M. (2013). Defunding dissent: Restrictions on aid to NGOs. Journal of Democracy, 24, 77–91.

CIVICUS Monitor. (2019). National civic space ratings. CIVICUS. Retrieved December 13, 2019, from www.monitor.civicus.org. .

Crotty, J., Hall, S. M., & Ljubownikow, S. (2014). Post-Soviet civil society development in the Russia Federation: The impact of the NGO law. Europe-Asia Studies, 66, 1253–1269.

Drevs, F., Tscheulin, D. K., & Lindenmeier, J. (2014). Do patient perceptions vary with ownership status? A study of nonprofit, for-profit, and public hospital patients. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43, 1164–1184.

Dupuy, K., & Prakash, A. (2018). Do donors reduce bilateral aid to countries with restrictive NGO laws? A panel study, 1993–2012. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47, 86–106.

Dupuy, K., Ron, J., & Prakash, A. (2016). Hands off my regime! Governments’ restrictions on foreign aid to non-governmental organizations in poor and middle-income countries. World Development, 84, 299–311.

Easterly, W. R. (2006). The white man’s burden: Why the west’s efforts to aid the rest have done so much ill and so little good. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Future Agenda. (2018). Future of philanthropy: Insights from multiple expert discussions around the world. London: Future Agenda.

Gersick, K. E., Lansberg, I., & Davis, J. A. (1990). The impact of family dynamics on structure and process in family foundations. Family Business Review, 3, 357–374.

Gersick, K. E., Stone, D., Grady, K., Desjardins, M., & Muson, H. (2004). Generations of giving: Leadership and continuity in family foundations. New York: Lexington Books.

Goss, K. A. (2016). Policy plutocrats: How America’s wealthy seek to influence governance. PS: Political Science & Politics, 49, 442–448.

Grønbjerg, K. A. (2006). Foundation legitimacy at the community level in the United States. In K. Prewitt, M. Dogan, S. Heydemann, & S. Toepler (Eds.), The legitimacy of philanthropic foundations: United States and European perspectives. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gunther, M. (2017). The charity that big tech built. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 15, 18–25.

Handy, F., Seto, S., Wakaruk, A., Mersey, B., Mejia, A., & Copeland, L. (2010). The discerning consumer: Is nonprofit status a factor? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39, 866–883.

Hayes, T. (1996). Management, control and accountability in nonprofit/voluntary organizations. Brookfield: Ashgate.

Herzlinger, R. E. (1996). Can public trust in nonprofits and governments be restored? Harvard Business Review, 74, 97–107.

Heydemann, S., & Kinsey, R. (2010). The state and international philanthropy: The contribution of American foundations. In H. K. Anheier & D. C. Hammack (Eds.), American foundations: Roles and contributions (pp. 1919–1991). Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Hopkins, B. R., & Blazek, J. (2014). Private foundations: Tax law and compliance (4th ed.). Hoboken: Wiley.

Horvath, A., & Powell, W. W. (2016). Contributory or disruptive: Do new forms of philanthropy erode democracy? In R. Reich, C. Cordelli, & L. Bernholz (Eds.), Philanthropy in democratic societies: History, institutions, values. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Howell, J., Ishkanian, A., Obadare, E., Seckinelgin, H., & Glasius, M. (2008). The backlash against civil society in the wake of the long war on terror. Development in Practice, 18, 82–93.

Ibrahim, B. (2015). States, public space, and cross-border philanthropy: Observations from the Arab transitions. International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law, 17, 72–85.

ICNL. (2019). Civic freedom monitor. International center for not-for-profit law. Retrieved December 13, 2019, from https://www.icnl.org/resources/civic-freedom-monitor.

IUPUI Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. (2019). Giving USA 2019: The annual report of philanthropy for the year 2018. Chicago: Giving USA.

Ivanova, E., & Neumayr, M. (2017). The multi-functionality of professional and business associations in a transitional context: Empirical evidence from Russia. Nonprofit Policy Forum, 8, 45–70.

Karl, B. D., & Katz, S. N. (1981). The American private philanthropic foundation and the public sphere 1890–1930. Minerva, 19, 236–270.

Kohl-Arenas, E. (2015). The self-help myth: How philanthropy fails to alleviate poverty. Oakland: University of California Press.

Kramer, R. M. (1981). Voluntary agencies in the welfare state. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Krasner, S. D. (1999). Sovereignty: Organized hypocrisy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Leviten-Reid, C. (2012). Organizational form, parental involvement, and quality of care in child day care centers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41, 36–57.

Longhofer, W., & Schofer, E. (2010). National and global origins of environmental association. American Sociological Review, 75, 505–533.

Madoff, R. (2016). When is philanthropy? How the tax code’s answer to this question has given rise to the growth of donor-advised funds and why it’s a problem. In R. Reich, C. Cordelli, & L. Bernholz (Eds.), Philanthropy in democratic societies: History, institutions, values. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

McGinnis Johnson, J. (2016). Necessary but not sufficient: The impact of community input on grantee selection. Administration & Society, 48, 73–103.

McGoey, L. (2015). No such thing as a free gift: The gates foundation and the price of philanthropy. London: Verso.

Meyer, B. D. (1995). Natural and quasi-experiments in economics. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 13, 151–161.

Meyer, J. W., Boli, J., Thomas, G. M., & Ramirez, F. O. (1997). World society and the nation-state. American Journal of Sociology, 103, 144–181.

Meyer, M., Moder, C., Neumayr, M., & Vandor, P. (2020). Civil society and its institutional context in CEE. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 31, 811–827.

Misch, P. M. (1989). Ecological security and the need to reconceptualize sovereignty. Alternatives, XIV, 389–427.

Moder, C., & Pranzl, J. (2019). Civil society capture? Populist modification of civil society as an indicator for autocratization. In Paper presented at SPSA annual conference 2019, Dreiländertagung, Zürich.

Mosley, J. E., & Galaskiewicz, J. (2015). The relationship between philanthropic foundation funding and state-level policy in the era of welfare reform. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44, 1225–1254.

Oelberger, C. R. (2018). Cui bono? Public and private goals in the design of nonprofit organizations. Administration & Society, 50, 973–1014.

Ravishankar, N., Gubbins, P., Cooley, R., Leach-Kemon, K., Michaud, C. M., Jamison, D. T., et al. (2009). Financing of global health: Tracking development assistance for health from 1990 to 2007. Lancet, 373, 2113–2124.

Reich, R. (2018). Just giving: Why philanthropy is failing democracy and how it can do better. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Reis, K., & Warren, S. (2016). International grantmaking made easier for US foundations. Alliance Magazine, 21, 20.

Rey-Garcia, M., & Puig-Raposo, N. (2013). Globalisation and the organisation of family philanthropy: A case of isomorphism? Business History, 5, 1019–1046.

Roelofs, J. (2015). How foundations exercise power. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 74, 654–675.

Rutzen, D. (2015). Aid barriers and the rise of philanthropic protectionism. International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law, 17, 5–44.

Saunders-Hastings, E. (2018). Plutocratic philanthropy. The Journal of Politics, 80, 149–161.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tilly, C. (1990). Coercion, capital, and European states. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers.

Tompkins-Stange, M. E. (2016). Policy patrons: Philanthropy, education reform, and the politics of influence. Cambridge: Harvard Education Press.

Villanueva, E. (2018). Decolonizing wealth: Indigenous wisdom to heal divides and restore balance. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

von Schnurbein, G. (2010). Foundations as honest brokers between market, state, and nonprofits through building social capital. European Management Journal, 28, 413–420.

Wolff, C. (1934 [1764]) Jus gentium methodo scientifica pertractatum. The Clarendon Press, Oxford.

World Bank. (2019). World Bank Country and Lending Groups. World Bank, Retrieved December 13, 2019, from, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oelberger, C.R., Shachter, S.Y. National Sovereignty and Transnational Philanthropy: The Impact of Countries’ Foreign Aid Restrictions on US Foundation Funding. Voluntas 32, 204–219 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00265-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00265-y