Abstract

The goal of the present study was to examine differences in self-esteem between volunteers with physical disabilities and their counterparts who do not volunteer. Another goal was to examine the contribution of the characteristics of the volunteering experience (motives for volunteering, satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering, and the quality of relationships with beneficiaries) to explain self-esteem among volunteers with physical disabilities. The research sample included 160 Israeli participants with different physical disabilities. Of these, 95 volunteered and 65 did not volunteer. Participants who volunteered had higher self-esteem than those who did not. The findings highlight the compensatory role of volunteering for people with disabilities: The contribution of volunteering to enhancing self-esteem was mainly evident among participants with poor socioeconomic resources (low education, low economic status, and unemployed). Egoistic and altruistic motives for volunteering as well as satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering contributed to explaining self-esteem.

Résumé

La présente étude a pour but d’examiner les différences qui existent dans l’estime de soi des bénévoles aux prises avec des handicaps physiques et leurs homologues non bénévoles. Elle cherche aussi à examiner la contribution des caractéristiques de l’expérience bénévole (motifs, satisfaction offerte par les récompenses du bénévolat et qualité des relations avec les bénéficiaires) pour expliquer l’estime de soi que ressentent les bénévoles handicapés. L’échantillon incluait 160 participants israéliens vivant avec divers handicaps physiques. De ce nombre, 95 étaient bénévoles et 65 ne l’étaient pas. Les participants bénévoles avaient une plus grande estime de soi que les non-bénévoles. Les résultats soulignent le rôle compensatoire du bénévolat chez les personnes vivant avec un handicap: la contribution du bénévolat envers l’estime de soi était principalement évidente parmi les participants jouissant de ressources socioéconomiques médiocres (faible niveau d’éducation, bas statut économique et sans-emploi). L’estime de soi s’expliquait en partie par la présence de motifs égoïstes et altruistes incitant au bénévolat et la satisfaction offerte par ses récompenses.

Zusammenfassung

Das Ziel der vorliegenden Studie war es, die Unterschiede im Selbstwertgefühl zwischen körperlich behinderten Personen, die sich ehrenamtlich engagieren und denen, die nicht ehrenamtlich tätig sind, zu untersuchen. Ein weiteres Ziel war die Untersuchung dahingehend, wie die Erfahrung im Rahmen der ehrenamtlichen Tätigkeit (Motive für das ehrenamtliche Engagement, Zufriedenheit mit der Belohnung für das ehrenamtliche Engagement und die Qualität der Beziehungen zu den Leistungsempfängern) zum Selbstwertgefühl körperlich behinderter Ehrenamtlicher beiträgt. Die Stichprobe umfasste 160 israelische Teilnehmer mit unterschiedlichen körperlichen Behinderungen. Davon waren 95 Personen ehrenamtlich tätig, während sich 65 Personen nicht ehrenamtlich engagierten. Die Ergebnisse unterstreichen die kompensatorische Rolle der ehrenamtlichen Tätigkeit für behinderte Menschen: Die Erhöung des Selbstwertgefühls aufgrund einer ehrenamtlichen Tätigkeit war hauptsächlich bei Teilnehmern festzustellen, die über geringe sozioökonomische Ressourcen verfügen (niedriger Bildungsstand, niedriger ökonomischer Status und Arbeitslosigkeit). Egoistische und altruistische Motive für ein ehrenamtliches Engagement sowie die Zufriedenheit mit der Belohnung für die ehrenamtliche Arbeit trugen zur Erklärung des Selbstwertgefühls bei.

Resumen

La meta del presente estudio era examinar las diferencias en la autoestima entre voluntarios con discapacidades físicas y sus contrapartes que no realizan voluntariado. Otra meta era examinar la contribución de las características de la experiencia del voluntariado (motivos para realizar voluntariado, satisfacción con las recompensas del voluntariado, y la calidad de las relaciones con los beneficiarios) para explicar la autoestima entre los voluntarios con discapacidades físicas. La muestra de la investigación incluyó a 160 participantes israelíes con diferentes discapacidades físicas. De estos, 95 realizaban voluntariado y 65 no lo hacían. Los participantes que realizaban voluntariado tenían una mayor autoestima que aquellos que no lo realizaban. Los hallazgos resaltan el papel compensatorio del voluntariado para las personas con discapacidad: la contribución del voluntariado para mejorar la autoestima resultó especialmente evidente entre los participantes con recursos socioeconómicos bajos (baja educación, bajo estatus económico, y desempleado). Los motivos egoístas y altruistas para realizar voluntariado, así como la satisfacción con las recompensas del voluntariado contribuyeron a explicar la autoestima.

Chinese

本研究的目的在于探究身体残障志愿者以及非志愿者身体残障人士之间在自尊方面的不同。另一个目标在于探究志愿经验特征的贡献(志愿行为的动机、志愿行为回报带给人的满足感以及与受益人关系质量),以为身体残障志愿者的自尊提供解释。研究样本包括160名具有不同身体残疾的参与者。在这些参与者中,95名曾参加志愿活动,而65名未曾参加志愿活动。与那些不曾参加志愿活动的参与者而言,曾参加志愿活动的参与者具有较高自尊。研究结果凸显了志愿行为对于残障人士的补偿作用:志愿行为在增强自尊方面的贡献主要那些社会经济资源较为贫乏(教育水平较低、经济状况较差以及失业者等)的参与者中有明显表现。志愿行为的利己与利他动机以及从志愿行为回报中所获得的满足感为这种自尊增强提供了解释。

Arabic

كان الهدف من هذه الدراسة هو فحص الإختلافات في تقدير الذات بين المتطوعين ذوي الإعاقة الجسدية ونظرائهم الذين لا يتطوعون. كان هدف آخر هو دراسة مساهمة خصائص التجربة التطوعية (دوافع التطوع، الإرتياح لمكافآت التطوع، وجودة العلاقات مع المستفيدين) لشرح إحترام الذات لدى المتطوعين ذوي الإعاقات الجسدية. شملت عينة البحث 160 مشارك إسرائيلي يعانون من إعاقات جسدية مختلفة. من بين هؤلاء، 95 تطوعوا و 65 لم يتطوعوا. كان المشاركون الذين تطوعوا لديهم إحترام الذات أعلى من أولئك الذين لم يفعلوا ذلك. تسلط النتائج الضوء على الدور التعويضي للعمل التطوعي بالنسبة للمعاقين: فقد كان إسهام التطوع في تعزيز إحترام الذات واضح بشكل أساسي بين المشاركين ذوي الموارد االجتماعية-الإقتصادية الضعيفة (تعليم منخفض، وضع إلقتصادي منخفض، العاطلين عن العمل). قد ساهمت دوافع التطوع الأناني والإغواء على العمل التطوعي، فضلا” عن الإرتياح لمكافآت التطوع، في تفسير إحترام الذات.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent decades have brought developments in legislation on rights for people with disabilities in Western countries, reflecting changes in social attitudes toward this population. Whereas in the past people with disabilities were viewed as needy and were socially excluded, their right to be actively involved in all areas of life is now emphasized. Concomitantly, major changes have occurred in how people with disabilities feel about contributing to the community through volunteer activity (e.g., Balandin et al. 2006). Moreover, when people with disabilities volunteer, their contribution to the community is substantial (Hall 2010; Miller et al. 2002). These individuals may benefit from volunteer activity personally as well as socially. On the personal level, volunteering enhances well-being. In this vein, Barlow and Hainsworth (2001) revealed that volunteering alleviates the sense of alienation experienced by people with disabilities. On the social level, volunteering reduces stereotypes about this population and consequently their social exclusion (Patterson 2001). However, it has been argued that despite these changes, many people with disabilities still have lower self-esteem than those without disabilities (Corrigan et al. 2006). The factors leading to low self-esteem among this population include functional dependence on their environment and exclusion from many social and community activities (Andrews 2005; Cohen 2008). In the present study, it was assumed that, like socioeconomic and environmental resources, volunteering is a resource in itself, one that contributes to enhancing the self-esteem of people with disabilities over and above the contribution of other resources at their disposal. Thus, volunteers with disabilities can be expected to have higher self-esteem than their counterparts who do not volunteer. After analyzing the differences in self-esteem among volunteers with disabilities compared with their counterparts who do not volunteer, we focus specifically on the sample of volunteers and examine which of the variables related to their experience of volunteering explain their self-esteem.

Conceptual Framework: Resources and Self-Esteem

Self-esteem is viewed by researchers in the field as a main predictor of adjustment to the environment (Orth et al. 2016). The concept refers to the positive or negative perceptions that individuals have of various aspects of themselves (Schmitt and Allik 2005). People with high self-esteem tend to be happier, healthier, more creative, better at performing complex tasks, and better at supporting others than people with low self-esteem (Smith and Grant-Mackie 1995). While most researchers in the field characterized self-esteem as stable over time (Kreger 1995), there is some evidence that self-esteem fluctuates as a function of individuals’ life experiences (e.g., Mullis et al. 1993; Pearlin et al. 1981), appreciation, and the quality of their relationships with others (Denissen et al. 2008). Moreover, a common assumption is that resourceful people have higher self-esteem than those with fewer resources (Diener and Diener 1995).

In the present study, we adopted the broad definition of the term resource as reflected in the conservation of resources theory (COR; Hobfoll 2001). According to COR, resources can be objects, conditions, personal characteristics, or energy that helps individuals cope with stressful situations. Using this definition, we examined the contribution of a diverse range of economic, personal, and environmental resources to explaining self-esteem among people with disabilities. In addition, owing to the substantial contribution of volunteering to people with disabilities, and based on Hobfoll’s (2001) broad definition of resources, we see volunteering as a resource that contributes to increased self-esteem among volunteers with disabilities, over and above the other resources at their disposal.

Positive Correlates of Resources

Availability of resources has the potential to enhance well-being in various ways. We focused on examining the contribution of socioeconomic resources (education, income, and employment status), health, and family support to explaining self-esteem among people with physical disabilities. In addition, we examined the contribution of volunteering status (volunteer and non-volunteer) as a resource that enhances self-esteem over and above the contribution of the above-mentioned resources.

Socioeconomic Resources

The chances of being accepted to senior job positions are greater for people with higher education than for those with less education (Hilton and Kopera-Frye 2004). In addition, when people with disabilities have higher levels of education they tend to be more involved in society, and they report higher levels of belonging and contributing to the community, than those with less education (Artman-Bergman and Rimerman 2009). In this vein, Gyamfi et al. (2001) found a negative correlation between income level and emotional distress. Specifically, they found that high income enables people to alleviate certain stress situations by purchasing services that facilitate coping.

As for employment, the contribution of this resource to enhancing self-esteem can be understood by examining the damage caused by unemployment, especially prolonged unemployment. Lack of employment is considered a passive and non-productive situation contributing to a decline in self-esteem (Kanungo 1982; Paul and Moser 2006). Against this background, which reveals an association between socioeconomic resources and different aspects of adaptation, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 1

The greater the socioeconomic resources of participants, the higher their self-esteem.

Health Resources

Good health has the potential to contribute directly to well-being, and because good health enhances physical and social functioning, it also increases self-esteem (Megel et al. 1994). Thus, besides their direct contribution, health resources might also contribute to different aspects of well-being indirectly. In other words, good health enables individuals to accumulate economic and social resources that facilitate coping with daily stressors (Danziger et al. 2000), thereby also increasing self-esteem. Conversely, because poor health has the potential to reduce one’s sense of mastery and increase dependence on one’s surroundings, it might lower self-esteem (Cohen et al. 2007). Based on this background, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 2

The better the health status of participants, the higher their self-esteem.

Family Support

One of the most important agents for social support is the family, which can provide individuals with security, empathy, encouragement, love, and activities that offer comfort and reassurance (Nowinski 1990). In line with this contention, Diener and Diener (1995) found a relationship between satisfaction with family support and self-esteem. Moreover, a recent study of people with disabilities in Israel found family support to be related to well-being, psychological empowerment, political empowerment, and community coherence (Barda 2015). Based on these findings, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 3

The higher the levels of family support of participants, the higher their self-esteem.

Volunteering

Based on Hobfoll’s (2001) broad definition of resources, volunteering in itself can be seen as a personal resource that might enhance self-esteem. For example, researchers have found a relationship between volunteering and positive outcomes, such as adaptive behavior among people with disabilities, which may result in enhanced self-esteem (Balandin et al. 2006). Volunteering has also been found to enable individuals with disabilities to form lasting, meaningful relationships with the beneficiaries of their work and with the community, which foster a sense of belonging (Griffel and Katash 2001). Roker et al. (1998) found that volunteer activity generates a sense of achievement and success among adolescents with disabilities and helps shift their focus from their personal difficulties to broader social issues. Volunteering strengthens social networks, improves social skills, enables people to make decisions about the future, and expands social connections (Roker et al. 1998).

Besides the empirical evidence linking volunteering and self-esteem, we may base this relationship on the role enrichment theory, developed initially to explain the contribution of fulfilling the role of the worker among women (Marks 1977). According to this approach, performing multiple roles offers three types of benefits. First, performing multiple roles can increase the supply of resources that people have at their disposal (e.g., financial resources gained from work and social resources gained from cooperation with colleagues). Second, success in one role can compensate for a sense of failure in another, thereby mitigating the negative effects of failure on personal well-being. Third, when people engage in multiple roles, they may feel that they are realizing their potential, which can foster a sense of self-worth and meaning in life (Greenhaus and Powell 2006). Thus, people with disability may benefit from fulfilling the role of volunteer in addition to their other roles, and consequently, they may have higher self-esteem than those who do not volunteer. In light of the positive outcomes of volunteering for the well-being of individuals, as reflected in the enrichment theory as well as in the above-mentioned empirical evidence, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 4

Volunteers with disabilities will have higher self-esteem than their counterparts who do not volunteer.

In addition to the direct effect of volunteering on self-esteem, and given the high potential of volunteering to empower people with disabilities, we assumed that volunteers with low levels of resources will benefit most from the contribution of volunteering. This assumption is based on the approach of Baltes and Baltes (1993), who argued that one of the strategies for adapting to loss of resources or crisis situations is compensation with other resources available to the individual. Thus, owing to the potential inherent in volunteering as a resource that can empower people with disabilities, we assumed that volunteering would compensate for the lack of personal and social resources:

Hypothesis 5

Volunteering will interact with each of the other resources (socioeconomic, health, and family support) in explaining self-esteem: The contribution of volunteering to enhancing self-esteem will be greater for participants with low resources than for those with high resources.

The Volunteering Process: Antecedents, Experiences, and Self-Esteem

Having established the relationship between volunteering and self-esteem, we focused on the volunteering participants only and examined the factors deriving from the volunteering process and contributing to explaining participants’ sense of self-esteem. According to Omoto and Snyder’s (1990) integrative conceptual framework, the volunteering process has three stages: antecedents of volunteering, the experience of volunteering, and the consequences of volunteering.

Antecedents of Volunteering

The antecedents of volunteering [Stage 1 in Omoto and Snyder’s (1990) model] may include barriers to as well as facilitators of volunteering, such as personal and social needs and motives for volunteering. In the present study, we focused on the motives for volunteering that may prompt people to enter the volunteering process and to be involved and committed to their activity. In many domains of life, motives drive individuals to act in a certain direction and to continue acting to attain a certain goal (Patall et al. 2008). Researchers have emphasized the relationship between motives and self-esteem (Leonard et al. 1999). There are several accepted approaches to presenting typologies of volunteering motives; some researchers posited a multidimensional approach to motives for volunteering (Clary et al. 1992; Okun et al. 1998; Omoto and Snyder 1990) while others presented a unidimensional (Cnaan and Goldberg-Glen 1991) or a two-dimensional approach to motives for volunteering (Frisch and Gerrard 1981). In the present study, we adopted a multidimensional approach to motives for volunteering as expressed in three basic motive dimensions. In this vein, we adopted Gillespie and King’s (1985) typology of volunteering motives, including altruistic motive and egoistic motives. However, following other researchers who presented more detailed typologies of motives for volunteering (for a summary, see Musick and Wilson 2007), we included also the motive of conforming to social norms and expectations (henceforth conformist motives), mentioned by Avrahami and Dar (1993) as a major motive for volunteering. People with conformist motives seek acceptance by engaging in activities that confer social legitimacy and social prestige (Kulik and Megidna 2011).

In line with Hobfoll’s (2001) broad definition of resources, we can view motives for volunteering that reflect high levels of energy and commitment to help others as a type of personal resource. Further to this argument, Kulik (2007) revealed the intensity of motives for volunteering among volunteer youth in Israel to be positively associated with psychological empowerment. Moreover, Kulik et al. (2016) revealed that among volunteers in a military emergency situation, a high level of motivation to volunteer was associated with high adaptation to stressful circumstances as reflected in positive affect. Based on these findings, which highlight the role of motives for volunteering as a personal resource available to volunteers, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 6

The stronger the motives for volunteering of participants, the higher their self-esteem.

Experience of Volunteering

The experience of volunteering [Stage 2 in Omoto and Snyder’s (1990) model] itself is mostly reflected by volunteers’ feelings during the process. In the present study, participants’ satisfaction with volunteering rewards and their assessment of the quality of their relationship with their clients reflected the experience of volunteering. These two aspects of the volunteering experience may promote or deter volunteers’ involvement (Kulik and Megidna 2011; Omoto and Snyder 1990).

Satisfaction with Volunteering Rewards

Satisfaction with volunteering activity is expressed in a positive assessment of volunteering as fulfilling the volunteer’s needs and as enabling implementation of values that are important to the volunteer (for a summary, see Pauline 2011). The basic theory for explaining satisfaction with frameworks of activity in different social contexts (such as work or family) is the classical social exchange theory (Blau 1964), which also serves researchers assessing satisfaction with volunteering (e.g., Rice and Fallon 2011; Zehrer and Hallmann 2015). In the volunteering context, volunteers may gain a variety of rewards either tangible, like gaining experience, or intangible, like attention, affection, and a sense of meaning (Schnell and Hoof 2012). From this theory, it can be derived that satisfaction with rewards from volunteering activities revealed a positive exchange state for volunteers and therefore may promote different aspects of their well-being as reflected in their self-esteem. In this vein, Kulik et al. (2016) revealed, recently, an association between satisfaction with volunteers’ rewards and different aspects of volunteers’ well-being.

Quality of the Relationship with Beneficiaries

The quality of the volunteer’s relationship with beneficiaries is reflected in diverse patterns of interaction. For example, Gronvold (1988) included the components of understanding, confidence, fairness, respect, affection, closeness, and open communication in the concept of relationship quality. Other components of the concept include satisfying social interactions with beneficiaries, agreement on various issues, and volunteers’ perception of the importance of the relationship with beneficiaries (Jarret et al. 1985; Townsend and Franks 1997). Moreover, some researchers (Leary et al. 1995, 1998) theorized that self-esteem is primarily rooted in our relationships with others, or in the need to belong (Baumeister and Leary 1995); therefore, quality of interaction with others is a good predictor of individual well-being. It can therefore be argued that a high-quality relationship in the volunteer-beneficiary dyad can reinforce beneficiaries’ acceptance of volunteers and consequently enhance volunteers’ self-esteem.

Consequences of Volunteering

The volunteering process may have a variety of consequences [Stage 3 in Omoto and Snyder’s (1990) model] related to the organization in which the volunteers act, to society as a whole, and to the volunteers themselves. In the present study, we focused on the individual level and the consequences of the volunteering process as reflected in volunteers’ sense of self-esteem. Against this background, we proposed the following hypotheses related to the experience of volunteering and self-esteem:

Hypothesis 7

The greater the satisfaction of participants with the rewards of volunteering, the higher their self-esteem.

Hypothesis 8

The higher the quality of the relationship between volunteers and beneficiaries, the higher volunteers’ self-esteem.

In addition to the direct relationships between volunteers’ satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering, quality of the relationship with beneficiaries, and self-esteem, we assumed that variables reflecting satisfaction with the experience of volunteering would mediate the relationship between motives for volunteering and self-esteem. We based this contention on findings that motives for volunteering can play an important role in determining volunteers’ satisfaction (Moreno-Jiménez and Villodres 2010). Apparently, highly motivated volunteers will be oriented toward achieving the goals they set. Thus, they will focus on succeeding, and the intensity of their motivation to volunteer will contribute to their satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering. Consistent with this argument, Kulik et al. (2016) revealed that high motivation to volunteer is related to a higher level of satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering; and a higher level of satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering is related to psychological empowerment. Thus, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 9

Satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering will mediate the relationship between motives for volunteering and self-esteem among volunteers with disabilities.

Similarly, Kulik and Megidna (2011) revealed that high motivation to volunteer is related to assessment of high-quality relationships with beneficiaries. Moreover, they found satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering and the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries to be related to the experience of psychological empowerment. Against this background, we proposed the following:

Hypothesis 10

High-quality relationships with beneficiaries will mediate the relationship between motives for volunteering and self-esteem among volunteers with disabilities.

Summary of the Research Goals

Based on the assumption that volunteering is a personal resource and that resources enhance self-esteem, the main goal of the study was to identify the direct contribution of volunteer activity as well as the combined contribution of volunteering and other resources to explaining the sense of self-esteem among people with disabilities. After establishing the relationship between volunteer activity and self-esteem among volunteers with disabilities, another goal of the study was to examine which characteristics of the volunteering experience (e.g., motives for volunteering, satisfaction with different aspects of volunteering and quality of the relationship with beneficiaries), contribute to enhancing self-esteem among volunteers with disabilities.

Methods

Sample and Data Collection

The research sample included 160 participants with various physical disabilities. In general, the distribution by disability type was similar for the two research groups (volunteers and non-volunteers; see Table 1). The main types of disabilities were limb disabilities (approximately 35%), deafness (approximately 10%), blindness (approximately 10%), polio (approximately 5%), arthritis (approximately 10%), asthma (approximately 10%), neurological damage (10%), and impaired functioning due to other causes (10%). The sample was also balanced in distribution by gender (see Table 1). The average age of the participants was 44.37 years (SD = 23.14) in the group of non-volunteers and 38.36 years (SD = 16.36) in the group of volunteers.

For both research groups (volunteers and non-volunteers), data were collected through online questionnaires and through face-to-face distribution. To collect the online data, we constructed websites for each of the two research groups. For the volunteers, non-profit organizations working with people with physical disabilities distributed the link to the research questionnaire. The other questionnaires for volunteers were distributed in the field at the time of volunteer activity, and research assistants helped them complete the questionnaires as needed. For non-volunteers, some of the data were collected through online questionnaires, and the rest of the data were collected through questionnaires distributed at various organizations that provide assistance and run community activities for people with physical disabilities. Approximately 65% of the distributed questionnaires were returned.

Instruments

Common Questionnaires for Volunteers and Non-Volunteers

The following questionnaires were administered to the entire sample (volunteers and non-volunteers).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale

The questionnaire was developed by Rosenberg (1965) and translated into Hebrew by Hobfoll and Walfisch (1984). It consists of 10 items measuring self-esteem (e.g., “I feel I’m a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others”). Responses were based on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). One score was derived for each participant by computing the mean of the items in the questionnaire: The higher the score, the higher the participant’s self-esteem. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the questionnaire used in this study was 0.88.

Resources Questionnaire

The questionnaire included questions about the participants’ assessments of various resources at their disposal: socioeconomic resources, health status, and family support. Socioeconomic resources included three types of resources: economic situation, measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very bad) to 5 (very good); level of education, measured on the basis of years of schooling; and employment status, measured using a dichotomous scale (employed/not employed). Health status was measured with one question about participants’ self-assessments of their health. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very bad) to 5 (very good). Family support was measured with one question on the extent of support participants receive from their families. Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very little) to 5 (very much).

Background Questionnaire

The questionnaire covered a broad range of variables, including gender, age, marital status, number of children, and children’s ages.

Questionnaires for Volunteers

Motives for Volunteering

Motives for volunteering were examined via a 13-item instrument adapted by Kulik et al. (2016) from a questionnaire developed by Clary et al. (1992; see “Appendix”). For each item, participants were asked to indicate the strength of the motive to volunteer on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent). Varimax-rotated factor analysis revealed three factors that explained 65% of the variance in motives for volunteering (eigenvalue > 1) and represented three distinct content areas: altruistic motives (e.g., “I volunteer because helping others is important to me”), egoistic motives (e.g., “Volunteering helps me acquire or improve vocational skills”), and conformist motives (e.g., “I volunteer because the people I’m close to volunteer”). For each factor, one score was derived by computing the mean of the items: The higher the score, the stronger the motive. Kulik (2016) found that the volunteering motives assessed by this instrument vary according to the life stage of the volunteers. The Cronbach’s alpha internal reliabilities for egoistic and altruistic motives were 0.72 and 0.83, respectively, and the correlation between the two items that represented conformist motives was r = 0.59, p < .001.

Satisfaction with Rewards of Volunteering

The instrument was based on a questionnaire developed by Kulik (2001), which included 11 items that examine the extent of participants’ satisfaction with various aspects of volunteering that may be considered rewards of volunteering (e.g., “Please indicate your satisfaction with the amount of interest you experience through your volunteering activity.” Responses were based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent). One score was derived by computing the mean of the scores on the items: The higher the score, the more satisfied participants were with the rewards of volunteering. The Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability for the questionnaire used in this study was high (0.93).

Quality of Relationship with Beneficiaries

The questionnaire, developed by Kulik and Megidna (2011), examines volunteers’ assessments of their relationship with beneficiaries. We used a short form of the questionnaire, consisting of four items reflecting different dimensions of volunteers’ relationship with beneficiaries (e.g., “Please indicate the extent of agreement with your beneficiaries about the goals of your work as a volunteer”). Participants were asked to rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent). One score was derived by computing the mean of the items: The higher the score, the higher participants’ evaluation of the quality of relationships with beneficiaries. The Cronbach’s alpha internal reliability of the questionnaire used in this study was high (0.86).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in two stages. In the first stage, we focused on the entire sample, conducting comparative statistical analyses to examine differences between the two groups in levels of self-esteem and in resources at their disposal. In this stage we also examined the relationships between the different resources and volunteers’ self-esteem. In the second stage, which focused on the volunteer sample only, we conducted multivariate analyses to examine the sources of self-esteem deriving from the experience of volunteering.

Results

Self-Esteem, Resources, and Volunteering (Hypotheses1–5)

Differences between the two research groups (volunteers and non-volunteers) in levels of self-esteem and resources were examined based on t tests of independent samples. We found significant differences between the two groups in levels of self-esteem: Volunteers had higher self-esteem than non-volunteers (see Table 2). In addition, we found differences between the two groups in the assessment of health, economic situation, and family support: Volunteers’ assessments of their health, their economic situation, and their family support were higher than the corresponding assessments of non-volunteers. However, we found no differences in education or employment status between the two groups (see Table 1).

Contribution of Resources and Volunteering Status to Explaining Self-Esteem

We conducted hierarchical regression analysis to examine the contribution of resources to explaining self-esteem among volunteers, as well as the specific contribution of volunteering status (0 = non-volunteer; 1 = volunteer) to enhancing self-esteem over and above the other resources. In addition, we used this analysis to test Hypothesis 5 regarding the effect of the interaction between volunteering status and the other resources on self-esteem. As a preliminary analysis to the regression analysis, we calculated correlations between the explanatory variables (background variables and resources) and self-esteem (see Table 3).

Hierarchical Regression Equation for Explaining Self-Esteem Among Volunteers and Non-volunteers

In the first step, the background variables, gender, age, and religiosity were entered into the regression equation (see Table 4). We entered these variables in the first step of the regression to partial out their contribution from the contribution of the resources entered in the next steps. Other background variables were not entered into the equation because our previous bivariate analyses revealed that they did not correlate significantly with self-esteem. In the second step, we entered the resources available to participants: economic situation, education, employment status, health situation, and family support. In the third step, volunteering status (volunteer and non-volunteer) was entered. By entering volunteering status in the third step, we examined whether volunteer activity contributes to explaining the variance in self-esteem over and above the contribution of the resources entered in the previous steps of the regression analysis.

To examine whether volunteering status (volunteer and non-volunteer) moderates the relationship between the level of resources available to participants and their self-esteem, using a stepwise procedure we entered the interactions of each of the five resources (economic situation, employment status, education, family support, health situation) with volunteering status (volunteers, non-volunteers) separately in the fourth step of the regression equation (testing Hypothesis 5).

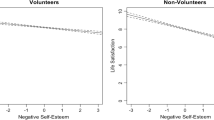

The background variables entered in the first step of the regression equation did not significantly explain the variance in participants’ self-esteem. However, the resources entered in the second step combined to explain approximately 20% of the variance in self-esteem. Of the resources, economic status and education level contributed significantly to explaining volunteers’ self-esteem: The higher the participants’ assessments of their economic situation and the higher their levels of education, the higher their self-esteem. Moreover, the addition of volunteering status (volunteers, non-volunteers), entered in the third step, explained 3% of the variance in self-esteem. In the fourth step, we found several significant interactions between resources and volunteering status (see Fig. 1a–c).

In this vein, we found a significant interaction between economic situation and volunteering status: Of the participants who assessed their economic situation as poor, self-esteem of volunteers was higher than self-esteem of non-volunteers. However, of the participants who assessed their economic situation as high, no differences were found between volunteers and non-volunteers (see Fig. 1a). The interaction between employment and volunteering status was in a direction similar to that for economic situation (see Fig. 1b): Among employed volunteers, differences in self-esteem by volunteering status were not significant. In contrast, unemployed volunteers had an advantage over unemployed non-volunteers: Unemployed participants who volunteered had higher self-esteem than non-volunteers (see Fig. 1b). Additionally, for educated participants we found no differences in self-esteem between volunteers and non-volunteers. However, for participants with low levels of education, volunteers had higher self-esteem than non-volunteers (see Fig. 1c). It can therefore be argued that volunteer activity benefits people with poor socioeconomic resources and enhances their self-esteem more than it does those with high levels of socioeconomic resources.

Explanation of Self-Esteem by the Experience of Volunteering

After finding that volunteer activity compensated for the lack of socioeconomic resources and enhanced participants’ self-esteem, we focused on volunteer participants only and examined the characteristics of the volunteering experience that explained self-esteem among that group. As a preliminary analysis to the regression analysis, we calculated correlations between the explanatory variables (background variables, motives for volunteering satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering, and the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries) and self-esteem (see Table 5).

Hierarchical Regression to Explain Self-Esteem Among Volunteers (Hypotheses 6–8)

In the first step of the hierarchical regression, the variables age and gender were entered as control variables (see Table 6). To test the mediation hypothesis (Hypothesis 7), we entered motives for volunteering (egoistic, altruistic, and conformist) in the second step and satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering and the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries in the third step.

The background variables entered in the first step combined to explain 7% of the variance in volunteers’ self-esteem, but their contribution was not significant. The addition of volunteering motives entered in the second step explained 24% of the variance in self-esteem. As shown in Table 6, conformist motives did not contribute significantly to volunteers’ self-esteem, whereas the contribution of altruistic and egoistic motives was significant. Notably, the beta coefficients indicate that these two motives contributed to explaining self-esteem in opposite directions: The stronger the participants’ altruistic motives for volunteering, the higher their self-esteem; and the stronger participants’ egoistic motives, the lower their self-esteem. In the third step, the addition of satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering and the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries explained an additional 15% of the variance in volunteers’ self-esteem. However, only satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering contributed significantly to that variance. As shown in Table 5, satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering was associated with the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries, and with self-esteem, indicating a possible mediation effect of satisfaction with rewards of volunteering between quality of the relationship with beneficiaries and self-esteem. To test this statement, we used the PROCESS procedure (Hayes 2013) and found that quality of the relationship with beneficiaries was related to satisfaction with rewards from volunteering (b = .43, p < .05) and that the latter were related to self-esteem (b = .52, p < .05). Thus, in this regression model, the effect of quality of the relationship with beneficiaries on self-esteem is mediated through the satisfaction with rewards of volunteering (ind. = .23, p < .05). For this analysis, we used the bootstrapping technique with number of repeats equal to 1000. The 95% confidence interval around the mediation estimate was provided.

Testing the Mediation Effect (Hypotheses 9–10)

As shown in Table 6 in the third step, when satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering and the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries were entered into the regression equation, the contribution of altruistic motives to explaining volunteers’ self-esteem was no longer significant.

The PROCESS procedure (Hayes 2013) was used to examine whether satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering and the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries mediate the relationship between motives for volunteering and self-esteem. Figure 2 indicates two full indirect effects.

Altruistic motives were found to have a full positive indirect effect on self-esteem through the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries (ind. = .10, p < .05): The stronger the volunteers’ altruistic motives, the higher the quality of their relationship with beneficiaries (b = .35, p < .001) and the higher the quality of their relationship with beneficiaries, the higher volunteers’ self-esteem (b = .28, p = .08). In addition, altruistic motives were found to have a full positive indirect effect on self-esteem through satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering (ind. = .25, p < .05): The stronger the volunteers’ altruistic motives, the higher their satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering (b = .49, p < .001) and the higher their satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering, the higher volunteers’ self-esteem (b = .52, p = .002). These findings indicate that high satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering and a positive relationship with beneficiaries mediated the relationship between altruistic motives for volunteering and self-esteem.

Discussion

The main goal of the study was to examine the contribution of volunteering as well as the contribution of other personal and environmental resources to enhancing self-esteem among people with disabilities. As expected, and consistent with the results of other studies in the field (Roker et al. 1998), the findings of the current study showed that volunteers with disabilities have higher self-esteem than their counterparts who do not volunteer (confirming Hypothesis 4). Volunteers were more empowered than non-volunteers, as reflected in their higher levels of health and some of the social economic resources and in their higher levels of family support. Moreover, the findings revealed a distinct contribution of volunteering to enhancing self-esteem, which remained significant after partialing out the contribution of the resources at the disposal of the volunteers. In addition to the direct contribution of volunteering to enhancing the self-esteem of people with disabilities, the interaction between volunteering status and socioeconomic resources highlights the compensatory contribution of volunteering to enhancing self-esteem among participants with poor socioeconomic resources (confirming Hypothesis 5).

Self-Esteem, Resources, and Volunteering

The findings related to the positive contribution of volunteering (direct and compensatory) for people with disabilities are in line with enrichment theory, which highlights the benefits of performing simultaneous multiple roles for increasing different aspects of subjective well-being (Marks 1977). Moreover, of the resources examined in the study, only economic resources and education contributed significantly to explaining self-esteem among people with disabilities (partially confirming Hypothesis 1). However, the contribution of health situation and family support was not significant (failing to confirm Hypotheses 2 and 3). Evidently, the finding that those two resources were not associated with self-esteem can be attributed to participants’ physical disabilities. As for the finding regarding health resources, it can be argued that, even when health indicators are good (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, body mass index), participants’ assessments of health may not have contributed to improving their self-esteem because of their limitations in daily functioning. As for family support, because the disability often renders participants dependent on assistance from others in their immediate environment, family support might in some cases emphasize their personal weakness. Thus, even if in some cases family support may increase a volunteer’s self-esteem, in other cases the positive effect of family support on self-esteem is diminished. Thus, overall, the impact of family support on self-esteem is found to be not significant. Following this explanation of the finding, the challenge for other researchers is to find under which conditions family support is related positively to self-esteem and under which conditions it is not. Overall, the findings that some of the resources at the disposal of people with disabilities are related to self-esteem, whereas others were not, highlight the need to adopt a contingent approach to exploring the effect of resources on well-being and self-esteem. According to this approach, the contribution of resources to individual well-being is neither permanent nor universal; rather, it depends on the circumstances and context of the individual’s activity (Kulik and Heine-Cohen 2008).

The Volunteering Process and Self-Esteem

Examination of the aspects of volunteering that contribute to explaining self-esteem among volunteers with disabilities revealed that the contribution of egoistic and altruistic motives was most significant (partially confirming Hypothesis 6). As expected, altruistic motives, which reflect a desire to help others, were positively associated with volunteers’ self-esteem: The stronger the participants’ altruistic motives, the higher their self-esteem. The positive association of altruistic motives in social interactions with enhanced self-esteem (Staub 1986) and with enhanced well-being in volunteering (Kulik et al. 2016) is supported by other research findings. Conversely, the findings revealed that the stronger participants’ egoistic motives, the lower their self-esteem. In this context, it has been argued that volunteers with egoistic motives experience distress and that they seek to improve their own well-being through volunteer activity (Kulik and Megidna 2011). Consistent with this view, people with egoistic motives are also characterized by an individualistic orientation, tend to be over-focused on themselves, and often experience loneliness (Hustinx and Lammertyn 2003). To alleviate that situation, they might seek to fulfill their need for companionship through volunteer activity (Musick and Wilson 2007). In such cases, the relationship between egoistic motives and self-esteem could be in the opposite direction; that is, the low self-esteem of these volunteers might motivate them to volunteer in order to improve their own situation. However, in light of the correlative design of the current study, this explanation cannot be fully supported, and longitudinal studies are needed to establish its validity.

The findings further reveal satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering to be positively associated with participants’ self-esteem (confirming Hypothesis 7). Evidently, the positive experience of appreciation and rewards for contributing to the community give these volunteers positive reinforcement, and the experience of success can enhance their self-esteem. The quality of the relationship with beneficiaries was not found to directly affect volunteers’ self-esteem (rejecting Hypothesis 8); however, its contribution was found to be indirect and mediated by the satisfaction with volunteering rewards construct. Apparently, a good relationship with beneficiaries creates a pleasing environment, leading to a tendency among participants to assess the different aspects of the volunteering activity as rewarding, which in turn raises their sense of self-esteem. Moreover, the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries plays another significant role in the volunteering experience; the relationship between altruistic motives and self-esteem was mediated by satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering and the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries (partially confirming Hypotheses 9 and 10). That is, the stronger volunteers’ altruistic motives, the more satisfied they were with the rewards of volunteering and the better their relationship with beneficiaries; when satisfaction with the rewards of volunteering and the quality of the relationship with beneficiaries was high, volunteers also had higher self-esteem.

To sum up, consistent with the results of an earlier study (Black and Living 2004), our findings revealed that volunteer activity can be considered an influential resource that benefits individuals with disabilities and improves their self-esteem directly as well as indirectly by compensating for the lack of other resources. For volunteers with disabilities, the findings further highlight the importance of fostering motives for volunteering, particularly altruistic motives, in light of their direct and indirect contribution to self-esteem.

Limitations of the Research and Practical Recommendations

First, the study was conducted with a small convenience sample. Secondly, resources were assessed based on one question and may not have been sufficiently comprehensive. Moreover, to ease responding to the research questionnaire for the participants with physical disabilities, we used relatively short instruments to assess the research construct. In addition, the research design was cross-sectional; thus, causal relationships between the explanatory variables (resources) and the outcome variable (volunteers’ self-esteem) cannot be determined. Finally, the study examined only volunteers with physical disabilities due to the difficulty involved in examining people with other disabilities such as cognitive disabilities. Further research in the field of volunteering among people with disabilities should address the limitations of the present study.

In light of the research findings, which highlight the contribution of volunteer activity to enhancing the self-esteem of people with disabilities, particularly for those with poor socioeconomic resources, there is a need to encourage volunteering among this population. Concomitantly, attempts should be made to break the personal and social barriers to volunteering among people with disabilities, including efforts to counter stereotypes held by volunteer coordinators as well as by beneficiaries of volunteer activity. Regarding facilitators of self-esteem among volunteers with disabilities, the findings highlight the importance of encouraging the development of altruistic motives, which were found to have high potential for increasing self-esteem among these individuals.

Change history

11 April 2018

The PDF version of this article was reformatted to a larger trim size.

References

Andrews, J. (2005). Wheeling uphill? Reflections of practical and methodological difficulties encountered in researching the experiences of disabled volunteers. Disability & Society, 20, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590500059341.

Artman-Bergman, T., & Rimerman, A. (2009). Dfusei meuravut hevratit bekerev anashim im ulelo mugbalut beyisrael [Patterns of social involvement among people with and without disabilities in Israel]. Bitahon Soziali [Social Security], 79, 49–84. (Hebrew).

Avrahami, A., & Dar, Y. (1993). Collectivistic and individualistic motives among kibbutz youth volunteering for community service. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 22, 697–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537138.

Balandin, S., Llewellyn, G., Dew, A., & Ballin, L. (2006a). “We couldn’t function without volunteers”: Volunteering with a disability, the perspective of not-for-profit agencies. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 29, 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mrr.0000191850.95692.0c.

Balandin, S., Llewellyn, G., Dew, A., Ballin, L., & Schneider, J. (2006b). Older disabled workers’ perceptions of volunteering. Disability & Society, 21, 677–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590600995139.

Baltes, P. B., & Baltes, M. M. (1993). Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (Vol. 4). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barda, R. (2015). Trumat hashiluv bein hahitarvut hapartanit vehahitarvut hakehilatit lehesber hosen nafshi bekerev peilim im mugbaluyot [The combined contribution of personal and community intervention to explaining psychological resilience among activists with disabilities]. Unpublished master’s thesis, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan (Hebrew).

Barlow, J., & Hainsworth, J. (2001). Volunteerism among older people with arthritis. Ageing & Society, 21, 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X01008145.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Black, W., & Living, R. (2004). Volunteerism as an occupation and its relationship to health and wellbeing. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67, 526–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260406701202.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., & Ridge, R. (1992). Volunteers’ motivations: A functional strategy for the recruitment, placement, and retention of volunteers. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 2, 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.4130020403.

Cnaan, R. A., & Goldberg-Glen, R. S. (1991). Measuring motivation to volunteer in human services. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886391273003.

Cohen, R. (2008). Manhigut noar leshinui amadot klapei anashim im mugbaluyot: Shinui amadot vedimui atzmi [Youth leadership to change attitudes toward people with disabilities: Attitude change and self-esteem]. Bitahon Soziali [Social Security], 78, 101–126. (Hebrew).

Cohen, M., Mansoor, D., Langut, H., & Lorber, A. (2007). Quality of life, depressed mood, and self-esteem in adolescents with heart disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69, 313–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e318051542c.

Corrigan, P. W., Watson, A. C., & Barr, L. (2006). The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25, 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875.

Danziger, S., Corcoran, M., Danziger, S., Heflin, C., Kalil, A., Levin, J., et al. (2000). Barriers to the employment of welfare recipients. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Poverty Research and Training Center.

Denissen, J. J., Penke, L., Schmitt, D. P., & Van Aken, M. A. (2008). Self-esteem reactions to social interactions: Evidence for sociometer mechanisms across days, people, and nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(1), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.181.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 653–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.653.

Frisch, M. B., & Gerrard, M. (1981). Natural helping systems: A survey of Red Cross volunteers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(5), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00896477.

Gillespie, D. F., & King, A. E. (1985). Demographic understanding of volunteerism. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 12, 798–816.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. N. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.19379625.

Griffel, A., & Katash, S. (2001). Doh mehkar letokhnit kehila tomehet hayim atzmayiim lenehim: Dfusei hitnadvut venehonut lehitnadev al-yedei haverim bakehila [Research report on the “supportive community for independent life for people with disabilities” program: Patterns of volunteering and willingness to volunteer among community members]. Jerusalem: JDC Israel, Disabilities Department (Hebrew).

Gronvold, R. L. (1988). Measuring affectual solidarity. In D. J. Mangen, V. L. Bengtson, & P. H. Landry Jr. (Eds.), Measurement of intergenerational relations (pp. 74–98). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Gyamfi, P., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Jackson, A. P. (2001). Associations between employment and financial and parental stress in low-income single black mothers. Women and Health, 32(1–2), 119–135. https://doi.org/10.1300/J013v32n01_06.

Hall, E. (2010). Spaces of social inclusion and belonging for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54, 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01237.x.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford.

Hilton, J. M., & Kopera-Frye, K. (2004). Patterns of psychological adjustment among divorced custodial parents. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 41(3–4), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v41n03_01.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50, 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062.

Hobfoll, S. E., & Walfisch, S. (1984). Coping with a threat to life: A longitudinal study of self-concept, social support, and psychological distress. American Journal of Community Psychology, 12(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00896930.

Hustinx, L., & Lammertyn, F. (2003). Collective and reflexive styles of volunteering: A sociological modernization perspective. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14, 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023948027200.

Jarret, R. L., Rodriguez, W., & Fernandez, R. (1985). Evaluation, tissue culture propagation, and dissemination of ‘Saba’ and ‘Pelipita’ plantains in Costa Rica. Scientia Horticulturae, 25, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4238(85)90085-8.

Kanungo, R. N. (1982). Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.67.3.341.

Kreger, D. W. (1995). Self-esteem, stress, and depression among graduate students. Psychological Reports, 76, 345–346. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1995.76.1.345.

Kulik, L. (2001). Mishtanei matzav veishiut hamevatim shehika nafshit bekerev mitnadvim [Situational and personality variables that reflect burnout among volunteers]. Jerusalem: National Insurance Institute. (Hebrew).

Kulik, L. (2007). Predicting responses to volunteering among adolescents in Israel: The contribution of personal and situational variables. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 18, 35–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-007-9028-6.

Kulik, L. (2016). Volunteering during an emergency: A life stage perspective. Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 46(2), 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016655621.

Kulik, L., Arnon, L., & Dolev, A. (2016). Explaining satisfaction with volunteering in emergencies: Comparison between organized and spontaneous volunteers in operation protective edge. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(3), 1290–1303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9671-2.

Kulik, L., & Heine-Cohen, E. (2008). Coping resources and adjustment to divorce among women: An ecological model. In J. K. Quinn & I. G. Zambini (Eds.), Family relations: 21st century issues and challenges (pp. 87–109). New York, NY: Nova Science.

Kulik, L., & Megidna, H. (2011). Women empower women: Volunteers and their clients in community service. Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 922–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20478.

Leary, M. R., Haupt, A. L., Strausser, K. S., & Chokel, J. T. (1998). Calibrating the sociometer: The relationship between interpersonal appraisals and the state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1290–1299.

Leary, M. R., Tambor, E. S., Terdal, S. K., & Downs, D. L. (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(3), 518–530. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.3.518.

Leonard, N. H., Beauvais, L. L., & Scholl, R. W. (1999). Work motivation: The incorporation of self-concept-based processes. Human Relations, 52, 969–998. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016927507008.

Marks, S. R. (1977). Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes on human energy, time and commitment. American Sociological Review, 42(6), 921–936.

Megel, M. E., Wade, F., Hawkins, P., & Norton, J. (1994). Health promotion, self-esteem, and weight among female college freshmen. Health Values: The Journal of Health Behavior, Education & Promotion, 18(4), 10–19.

Miller, K. D., Schleien, S. J., Rider, C., & Hall, C. (2002). Inclusive volunteering: Benefits to participants and community. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 36, 247–259.

Moreno-Jiménez, M. P., & Villodres, M. (2010). Prediction of burnout in volunteers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 1798–1818. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00640.x.

Mullis, R. L., Youngs, G. A., Mullis, A. K., & Rathge, R. W. (1993). Adolescent stress: Issues of measurement. Adolescence, 28(110), 267–279.

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2007). Volunteers: A social profile. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Nowinski, J. (1990). Substance abuse in adolescents and young adults: A guide to treatment. New York, NY: Norton.

Okun, M. A., Barr, A., & Herzog, A. R. (1998). Motivation to volunteer by older adults: A test of competing measurement models. Psychology and Aging, 13, 608–621. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.13.4.608.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (1990). Basic research in action volunteerism and society’s response to AIDS. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16(1), 152–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167290161011.

Orth, U., Robins, R. W., Meier, L. L., & Conger, R. D. (2016). Refining the vulnerability model of low self-esteem and depression: Disentangling the effects of genuine self-esteem and narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(1), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000038.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: A meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 270–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.270.

Patterson, I. (2001). Serious leisure as a positive contributor to social inclusion for people with intellectual disabilities. World Leisure Journal, 43(3), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/04419057.2001.9674234.

Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2006). Incongruence as an explanation for the negative mental health effects of unemployment: Meta-analytic evidence. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(4), 595–621. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X70823.

Pauline, G. (2011). Volunteer satisfaction and intent to remain: An analysis of contributing factors among professional golf event volunteers. International Journal of Event Management Research, 6(1), 10–32.

Pearlin, L. I., Menaghan, E. G., Lieberman, M. A., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22(4), 337–356.

Rice, S., & Fallon, B. (2011). Retention of volunteers in the emergency services: Exploring interpersonal and group cohesion factors. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 26(1), 18–23.

Roker, D., Player, K., & Coleman, J. (1998). Challenging the image: The involvement of young people with disabilities in volunteering and campaigning. Disability & Society, 13, 725–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599826489.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Self esteem and the adolescent. Science, 148, 804–821.

Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). Simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale in 53 nations: Exploring the universal and culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 623–642. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.62.

Schnell, T., & Hoof, M. (2012). Meaningful commitment: Finding meaning in volunteer work. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 33(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/13617672.2012.650029.

Smith, A. M., & Grant-Mackie, J. A. (1995). Differential abrasion of bryozoan skeletons: Taphonomic implications for paleoenvironmental interpretation. In D. P. Gordon, A. M. Smith, & J. A. Grant-Mackie (Eds.), Bryozoans in space and time: Proceedings of the 10th International Bryozoology Conference, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand (pp. 305–313). Wellington: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research.

Staub, E. (1986). A conception of the determinants and development of altruism and aggression: Motives, the self, and the environment. In C. Zahn-Waxler, E. M. Cummings, & R. J. Iannotti (Eds.), Altruism and aggression: Social and biological origins (pp. 135–164). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511752834.007.

Townsend, A. L., & Franks, M. M. (1997). Quality of the relationship between elderly spouses: Influence on spouse caregivers’ subjective effectiveness. Family Relations, 46, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/585604.

Zehrer, A., & Hallmann, K. (2015). A stakeholder perspective on policy indicators of destination competitiveness. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(2), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.03.003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I hereby confirm that there is no conflict of interest in publishing the attached article.

Ethical Standards

The research sample was treated according to ethical standards as was approved by the Institution Review board of School of Social Work—Bar Ilan university.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kulik, L. Through Adversity Comes Strength: Volunteering and Self-Esteem Among People with Physical Disabilities. Voluntas 29, 174–189 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9914-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9914-5