Abstract

Building on an analytical framework of agent-based institutionalization, this qualitative study uses narrative accounts to explore a historical evolution of Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy from the 1970s to 1990s. Using primary data, such as interviews with key actors and archival resources, as well as secondary and publication data, I examine the process of how Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy progressed simultaneously and how the American concept of philanthropy was integrated into different cultural contexts and emerged as the Japanese concept of philanthropy, firansoropii. This study also reveals that the three-decade process of institutionalizing Japanese philanthropy was driven by Japanese institutional actors who bridged the philanthropic, political, and economic boundaries between Japan and the United States.

Résumé

En se basant sur un cadre analytique d’institutionnalisation basée sur des agents, cette étude qualitative fait appel à des comptes rendus narratifs pour explorer l’évolution historique de la philanthropie japonaise et la philanthropie d’entreprise des années 70 à 90. Grâce à des données primaires, dont des entrevues d’acteurs clés et des ressources d’archive, ainsi qu’à des données secondaires et publiées, j’examine le processus d’évolution simultanée des philanthropies japonaise et d’entreprise, et la façon dont le concept américain de philanthropie a été intégré à un contexte culturel différent pour émerger comme concept japonais de la philanthropie, appelé firansoropii. La présente étude révèle que le processus d’institutionnalisation de la philanthropie japonaise, ayant duré trois décennies, a été favorisé par des acteurs institutionnels japonais qui ont rapproché les frontières philanthropiques, politiques et économiques entre le Japon et les É.-U.

Zusammenfassung

Aufbauend auf einem analytischen Rahmen der agentenbasierten Institutionalisierung stützt sich diese qualitative Studie auf narrative Darstellungen, um die historische Entwicklung der japanischen und korporativen Philanthropie zwischen den siebziger und neunziger Jahren zu erforschen. Anhand primärer Daten, wie zum Beispiel Interviews mit wichtigen Akteuren und Archivressourcen, sowie sekundärer und Publikationsdaten wird untersucht, wie sich die japanische Philanthropie und die korporative Philanthropie gleichzeitig fortentwickelten und wie das amerikanische Philanthropiekonzept in einen anderen kulturellen Kontext integriert wurde und als das japanische Philanthropiekonzept „Firansoropii“ hervorging. Darüber hinaus zeigt die Studie, dass der drei Jahrzehnte lange Institutionalisierungsprozess der japanischen Philanthropie von japanischen institutionellen Akteuren vorangetrieben wurde, die die philanthropischen, politischen und wirtschaftlichen Grenzen zwischen Japan und den USA überbrückten.

Resumen

Basándose en un marco analítico de la institucionalización basada en agentes, este estudio cualitativo utiliza relatos narrativos para explorar una evolución histórica de la filantropía japonesa y la filantropía corporativa de los años setenta a los noventa. Utilizando datos primarios, como entrevistas con actores claves y recursos de archivo, así como datos secundarios y de publicación, examino el proceso de cómo la filantropía japonesa y la filantropía corporativa progresaron simultáneamente y cómo el concepto americano de filantropía se integró en diferentes contextos culturales y surgió Como el concepto japonés de filantropía, firansoropii. Este estudio también revela que el proceso de tres décadas de institucionalización de la filantropía japonesa fue impulsado por actores institucionales japoneses que superaron las fronteras filantrópicas, políticas y económicas entre Japón y Estados Unidos.

要約

构建基础代理制度的分析框架,该项定性研究使用了叙述性语句,以便探索从20世纪70年代到20世纪90年代日本慈善事业和企业慈善的历史演变。通过使用原始数据,如:主要活动者的采访和档案资源,以及次级数据和出版材料,我调查了日本慈善事业和企业慈善是如何进展的,以及美国慈善事业概念是如何融入到不同的文化背景中并让日本慈善事业概念应运而生的。本研究也表明这30年日本慈善事业制度化是由日本机关人员推动的,这些人在日本和美国之间架起了慈善、政治和经济领域的桥梁

ملخص

البناء على إطار تحليلي لإضفاء الطابع المؤسسي القائم على جهات فعالة، تستخدم هذه الدراسة النوعية حسابات سردية لإكتشاف التطور التاريخي للعمل الخيري الياباني والعمل الخيري للشركات من 1970.1990- بإستخدام البيانات الأولية، مثل المقابلات مع الجهات الفاعلة الرئيسية والموارد الأرشيفية، كذلك البيانات الثانوية ونشرها، ودراسة عملية لكيف أن العمل الخيري الياباني والعمل الخيري للشركات تقدم في وقت واحد، وكيف تم دمج المفهوم الأمريكي للعمل الخيري في سياق ثقافي مختلف وتم إبراز المفهوم الياباني للعمل الخيري، (firansoropii) تكشف هذه الدراسة أيضا أن إجراءات ثلاثة عقود لإطفاء الطابع المؤسسي على العمل الخيري الياباني الذي كان يقوده الجهات المؤسسية اليابانية، التي أقامت جسور حدود خيرية سياسية و إقتصادية بين اليابان والولايات المتحدة الأمريكية.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While philanthropy has long been manifest in activities in most national and cultural contexts (Payton and Moody 2008), philanthropy as a concept has been fluid (Sulek 2010). How philanthropy is conceptualized and institutionalized varies across socio-economic, political, and cultural contexts (Einolf 2016; Wiepking and Handy 2016). The current study draws on a qualitative method to illuminate the coevolution of Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy from the 1970s to 1990s. According to prominent scholars and thought leaders of Japanese philanthropy (M. Deguchi, personal communication, December 8, 2015; Hayashi and Yamaoka 1993; Katsumata 2006; Shimada 1993), corporate philanthropy in the US–Japan context had a considerable impact on the institutionalization of philanthropy in Japan. The process of advancing Japanese philanthropy during this period—when Japan’s aggressive pursuit of economic expansion overseas generated a conflict between Japan and the United States—presents a unique picture of how institutionalization of Japanese philanthropy progressed beyond both national and sectoral borders.

The present study examines interactions and events between Japan and the United States, as well as within each country. It shows how Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy coevolved and how the American concept of philanthropy was integrated into a different cultural context. Contrary to individual-centered philanthropy in the United States, corporate giving has historically outpaced individual giving in Japan. In 1991, 93.9% of total giving in Japan came from corporations (Honma 1993). The aftermaths of devastating disasters, such as 1995 Great Hanshin Awaji earthquake and 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, have boosted individual giving, albeit temporarily (Ishida and Okuyama 2015). More recent data confirm the continued dominance of institutional giving over individual giving: Cabinet Office (2016), National Tax Agency (cited in Chuo Mitsui Trust and Banking Company 2011), and Yamauchi et al. (2004) show 80.9, 76.9, and 69.9% of total giving in Japan, respectively, came from institutions, mostly corporationsFootnote 1.

The philanthropy–corporate relationship that forms the focal case of this study is more complex than a simple recipient–funder relationship; rather, it created mutually beneficial effects on both sides. As detailed below, my analysis of interviews and archival data shows that back-stage (within the philanthropic circle) and front-stage (between the philanthropic circle and the corporate circle) interactions led to this coevolution of Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy. That is, while philanthropic leaders initially explored the Japanese concept of philanthropy—firansoropii フィランソロピー in Japanese—(Hayashi and Yamaoka 1993) within their own circle, field-configuring activities were being organized to convene philanthropic and corporate leaders. A symbiotic relationship between two communities not only facilitated the developing Japanese concept of philanthropy but also reflected the philosophy of businesses and corporate philanthropy (Aoki 2004).

The theoretical foundation of my analysis is institutional theory, in particular, the agent-based perspectives and structuration. Structuration (Giddens 1979) involves increased interactions among institutional actors, whether individuals or organizations, and develops a consensus on rules, norms, and cultural perceptions about new agreed upon practices. At the initial stage of structuration, institutional principles and legitimated norms are encoded in the scripts used in specific settings (Barley and Tolbert 1997) and diffused through field-configuring vehicles or “carriers” (Jepperson 1991). Those carriers include symbolic systems (e.g., new language), events and networks, and artifacts (e.g., publications). Following these theoretical implications, I below show how the institutionalization of Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy was driven by milestone events, initiatives, and networks. I also explain how this process was facilitated by actors, both organizations and individuals, who played a “boundary-bridging” role as theorized by institutional scholars (Greenwood and Suddaby 2006).

This study aims to make several contributions to the scholarship of philanthropy. First, it extends ongoing discussions about the meaning of philanthropy (Daly 2012; Sulek 2010). Scholarly efforts in this line are growing; yet existing studies have not looked into the process of conceptualizing philanthropyFootnote 2. Using the case of Japan, I unpack the process of how the Japanese concept of philanthropy was institutionalized, how the American concept of philanthropy was adapted in a different country, and how cultural and sociopolitical factors affected this process. Second, a recent review of the corporate philanthropy literature (Gautier and Pache 2013) stresses the need of a better understanding of the institutionalization process of corporate philanthropic practices. Research on corporate philanthropy has been rooted primarily in strategic management, such as strategies to promote business interests (Marx 1999) and foster stakeholder relationships (Burlingame and Young 1996; Cho and Kelly 2014). My study distinguishes itself by illuminating the historical process of how new ideas and practice of corporate philanthropy emerged and how the juxtaposition between the philanthropic circle and the corporate circle facilitated the process. Third, many meaningful publications, including articles written by the key actors, have enriched our understanding about history of Japanese philanthropy (Hayashi and Yamaoka 1993; Yamamoto et al. 2006) and Japanese corporate philanthropy (Aoki 2004; Kawazoe and Yamaoka 1987). Yet most extant studies were anecdote-based—theories, such as institutional theory, have rarely been applied to analyze the field of Japanese philanthropy—and published in Japanese for a Japanese audience, except limited notable efforts (e.g., Lohmann 1995). The current study complements the prior studies on Japanese philanthropy by applying institutional theory and speaking to a Western audience. Fourth, this study sheds light on the pivotal role that Japanese philanthropy played in advancing the US–Japan relationship. The important influence of philanthropy in international relations has been often overlooked (Iriye 2006). In the same vein, by scrutinizing primary data that reveals Japanese key actors’ enduring efforts to explore their own philanthropy, this study reevaluates the importance of Japanese corporate philanthropy, which was once called a “predatory act” (Johnson 1988).

Methods

My main objective is to examine the vital roles of key actors and events in constructing new ideas and concept of Japanese philanthropy. As such, the contextualization, vivid description, and dynamic structuring of actors’ socially constructed worlds (Lee 1999) are critical. The prior literature has not theoretically examined the process of developing Japanese philanthropy. A scarcity of research underlines that qualitative research is the most appropriate (Marshall and Rossman 2010).

Data Sources

I collected and employed a wide range of primary and secondary sources of data. The primary sources are as follows: (1) in-person interviews and correspondence exchanged between 2003 and 2016 with key actors who carried out historical events to advance Japanese philanthropy domestically and internationally from the 1970s to 1990s (personal communication with M. Deguchi, N. Hayase, H. Katsumata, T. Matsuoka, T. Ohta, Y. Takahashi, and Y. Yamaoka); (2) archival materials developed by the key actors and organizations, such as unpublished manuscripts (e.g., Yamaoka 2015), reports (e.g., The Toyota Foundation annual reports from 1977 to 1987; reports published in Japan Association of Charitable Organizations’ monthly publications, Koeki Hojin, from 1987 to 1991), books (e.g., Hayashi and Imada 1999; Hayashi and Yamaoka 1993; Kawazoe and Yamaoka 1987; Yamamoto et al. 2006), and other resources (e.g., Keidanren’s 1991 Charter for Good Corporate Behavior); and (3) publication records retrieved from Japan’s primary bibliographic databases; National Diet Library Online Public Access Catalog (NDL-OPAC, 267 records) and Scholarly and Academic Information Navigator (CiNii, 208 records). Secondary data sources include (1) books and articles written by both Japanese and Western authors, and (2) U.S. magazine and newspaper articles reporting Japanese corporate direct investment and giving in the United States.

Data Analysis

The data analysis comprised two stages. The first stage entailed a narrative strategy (Langley 1999) that chronicled major relevant events in Japan, in the United States, and between the two nations from the 1970s through the 1990s (Table 1). This comparative narrative revealed how key field-configuration activities occurred among the philanthropic and corporate circles in Japan and the United States, and between the two countries. But the chronological narrative alone did not allow me to isolate the fine-grained mechanisms accounting for the nature and motivation of key actors’ efforts to bridge boundaries. Thus, in the second stage, I scrutinized aforementioned primary sources. I also reviewed the secondary sources to comprehend how Japanese sources and Western sources perceived Japanese philanthropy differently. This comprehensive analytical process allowed me to identify the separate events occurring in each country and to form a counterargument to existing publications, especially those by Western critics.

Background

Philanthropic Tradition in Japan Before the 1970s

This section is an overview of philanthropic tradition in Japan before the 1970s, as compared to the large-scale institutionalization of Japanese philanthropy that began in the 1970s. Contrary to a popular view of Western critics as detailed below, existing studies underline a long and rich history of philanthropic activities in Japan under a strong Buddhist influence (Hayashi and Yamaoka 1993). The history of major philanthropic initiatives can be traced back to Hiden-in, a social welfare facility of the Buddhist temple, Shitenno-ji, built by Prince Shotoku during the seventh century (Imada 2006). Kanjin Footnote 3, a Japanese Buddhists’ organized fundraising effort, dating from the eighth century, resembled today’s capital campaign fundraising (Lohmann 1995). During the Edo period (1603–1868), the charitable power of Buddhism declined and a spirit of civil society emerged instead (Yamaoka 1998). The growing civil spirit was evident in Osaka, where wealthy merchants supported the creation of public facilities (Imada 2003) such as Akita Kan’on-ko, a community trust fund that a merchant from the Akita region created for promoting social welfare, education, and other activitiesFootnote 4 (Katsumata 2006). The Meiji period (1868–1912) produced successful industrialists, including Eichi Shibusawa and Ichizaemon Morimura. Influenced by both long-established Japanese traditions and American philanthropic ideas learned from the business and philanthropic circles in the United StatesFootnote 5 (Kimura 2006), Shibusawa and Morimura became prominent philanthropists in the premodern period.

A premodern example of corporate philanthropy in Japan is giving through zaibatsu (Katsumata 2006; Shimada 1993), conglomerates of influential family businesses. In 1911, when the Meiji Emperor founded On-shi Zaidan Saisei-kai (the Imperial Relief Association) to supply medical relief for the poor, the majority of seed money came from zaibatsu (Yamamoto and Amenomori 1989). After Japan’s defeat in 1945, the zaibatsu were dismantled and their foundations were either abolished or significantly reduced. Still, a limited number of companies, such as Suntory Holdings Limited (formerly known as Kotobukiya), established their corporate foundations in the 1920s to help build medical and social welfare facilities for low-income citizens (Shimada 1993). A number of major foundations incorporated during the 1930s (e.g., Asahi Glass Foundation), however, took on an increasingly national coloration, as the Home Ministry strengthened its control over the foundations amidst rising nationalism (Kimura 2006). Philanthropic activities by business corporations quickly began fading in the beginning of the Showa period (1926–1989). As a result, the prewar era saw only less than 20 corporate foundations established, although Article 34 of the 1896 Civil CodeFootnote 6 allowed for the establishment of koeki hojin (private non-profit activities) (Aoki 2004). Corporate philanthropy reemerged in Japan during the late 1950s, but they focused on the national priority to advance science and technology. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw a continued growth of corporate philanthropy in Japan, yet it primarily supported domestic projects fostering economic growth, given the government regulation ensuring that philanthropic activities supported official postwar priorities (Bestor 2005; Shimada 1993).

Several important characteristics of philanthropy and corporate philanthropy of pre-1970s Japan warrant attention before we examine the institutionalization of Japanese philanthropy during the 1970s and onward. First, despite the aforementioned long history of philanthropic activities, the meaning of philanthropic tradition in premodern Japan was rather limited to the relief aspect, as opposed to the Western multi-dimensional concept of philanthropy (Daly 2012). Japanese scholars (Kawazoe and Yamaoka 1987) indicate that early terms pertaining to philanthropic activities in Japan include jizen Footnote 7 (慈善) or jizen jigyo (慈善事業); jizen jigyo is defined as “social activities conducted on the basis of religious or moral motivations for such purposes as the relief of the ill, the elderly and infirm, or disaster victims” (Kimura 2006, p. 279). Second, the state’s influence over the Japanese mindset overpowered the growth of individual and corporate philanthropy from the late 1800s, until Japanese citizens’ trust in government began declining in the 1990s (Matsubara and Todoroki 2003). Despite the dedication of Shibusawa and other industrialists to philanthropy, the innovative spirit, autonomy, and the movement for popular rights—core principles of American philanthropy—had diminished in Japanese society after the Meiji Constitution was promulgated in 1889 (Kawazoe and Yamaoka 1987). Japanese perceptions shifted to being state-centeredFootnote 8; “public” meant the central government (Kimura 2006). Despite burgeoning movements and protests organized by Japanese citizens at the grassroots level prior to the 1970s (Bestor 2005; Haddad 2010), the state-centered mindset remained strong and shaped the nature of philanthropy and civil society in postwar Japan. In practice, philanthropic foundations were little more than branches of the government (Hayashi and Yamaoka 1984), and non-profit organizations, such as shakai fukushi kyogikai (social welfare associations), were established as quasi-governmental entities (Haddad 2010).

US–Japan Trade Conflicts: Impetus for Institutionalization of Japanese Philanthropy in the 1970s and After

This was the time when Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy began reemerging and constructing the new intuitional field, which Imada rightly calls “a renaissance of Japanese philanthropy” (cited in Shimada 1993). Yet early trigger for the large-scaled institutionalization of Japanese philanthropy was political and economic—the escalating tension in the US–Japan bilateral economic relationship. Postwar trade conflicts between two countries began with a surge in imports of Japanese cotton textiles in the mid-1950s and intensified throughout the 1980s. The mounting trade imbalance gave rise to antagonism among the American public against Japanese corporations, which led the US government to cite Japan under the Super 301 Law (King 1991). Although it was not the ultimate intention that Japanese philanthropic leaders bore (T. Ohta, personal communication, November 27, 2015), the existing records (e.g., Japan Center for International Exchange 1986) suggest that Japanese leaders turned to philanthropy for a solution to mediate the strain with the United States and repair Japanese corporations’ tainted images oversea.

As a result, the period of the 1970s–1980s saw the nexus between corporations and philanthropy became pronounced in US–Japan international relations. Japanese corporations began directing massive financial support to America’s largest arts organizations and universities as allowable tax-deductible contributions through the Keidanren and the Japan Foundation. Examples included three $1-million gifts to Harvard University within 2 years—the Mitsubishi group’s endowment of a chair in Japanese legal studies in 1972 and the Nissan Motor Company’s and Toyota Motor Corporation’s gifts to the Japan Institute in 1973 (Cramer 1974; Reynolds 1973; Schumer 1973). After the Plaza Accord of 1985, Japanese companies rapidly increased their foreign direct investment (FDI), which was also supported by the sharp appreciation of the yen (Y. Takahashi, personal communication, November 27, 2015). Japanese corporate philanthropy in the United States continued to escalate in both amount and scale throughout the 1980s. The New York Times (Teltsch 1989) reported that Japanese corporate giving in the United States jumped from $85 million in 1987 to $145 million in 1988.

Contrary to Japanese leaders’ hope, major gifts that Japanese companies had made to leading American universities generated vocal criticism over the authenticity and motivation behind their philanthropic acts. American critics characterized the massive giving of Japanese corporations as an attempt to camouflage the dramatic rise in Japanese FDI in the United States (The Taft Group 1989) or a quid pro quo arrangement, expecting the funded universities to provide direct benefits, such as data that otherwise would be unavailable (Epstein 1991). Western critics, such as London (1990), began perusing the Japanese tradition of philanthropy (or lack thereof). In her book, Japanese Corporate Philanthropy, London dictated that Japan was lacking individual philanthropic tradition and equivalent to the American concept of philanthropy. That is, the ethos of American philanthropy rooted in “love of mankind,” purely altruistic giving, and activities carried out for an anonymous public were cast as foreign concepts among the Japanese. She further attributed this absence of the American concept of philanthropy to Japanese corporations’ aggressive pursuit of economic gain out of their massive giving.

American critics’ perception about Japanese philanthropy contradicts Japanese authors’ explanation about the history of Japanese philanthropy, which I above discussed. A plausible reasoning behind this contradiction lies in distinct cultural values that have shaped Japanese philanthropy, such as Confucian and collectivism roots (Tucker 1998). Typical American philanthropic activities, such as donor recognition and face-to-face meetings, are traditionally uncommon in the society of Japan (Onishi 2007), which is deeply embedded by the idea of intoku (“good deeds done without recognition,” Matsubara and Todoroki 2003, p. 31). These attributes may make it very difficult for the non-Japanese observers to fully recognize philanthropic tradition in Japan.

Notwithstanding, American critics’ vocal disapprovals of massive giving by Japanese companies compelled Japanese corporate leaders to regroup their giving approach and Japanese philanthropic leaders to reflect upon their own philanthropic tradition. The subsequent sections examine these actors’ field-configuring activities from the agency-based institutional perspective. Structural-based institutional theory highlights the dominance of environment over organizational behaviors and reinforces conformity to institutional pressure. It theorizes that organizations mimic successful cases to gain legitimacy in the face of uncertainty (DiMaggio and Powell 1983). Thus, from the structural-based institutional perspective, Japanese companies’ massive giving could well be interpreted as a way to legitimate their existence in American society by mimicking a well-recognized giving style of prominent American philanthropists (e.g., Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller) who supported major arts organizations and universities. The agent-based institutional perspective gives us different insights into how Japanese actors institutionalized a new field of Japanese philanthropy. What has not been well understood is that behind the lavish philanthropy of Japanese corporations were serious efforts by a group of Japanese philanthropic and corporate leaders—as border-bridging institutional actors—to adapt American philanthropy and explore their own philanthropy during the same time when Western critics disparaged Japanese corporate philanthropy. Table 1 shows that initiatives advancing Japanese philanthropy emerged early in the 1970s, two decades before London’s book (1990) was published. I below detail the wide range of efforts that advanced Japanese philanthropy across national and sectoral boundaries from the 1970–1990s.

Efforts Advancing Japanese Philanthropy Beyond National and Sectoral Borders

Major Actors for Bridging National and Sectoral Borders

Institutionalizing Japanese philanthropy during the late twentieth century evolved across both national (United States and Japan) and sectoral (corporate, political, philanthropic) borders. This process was driven by actors who played a “boundary-bridging” (Greenwood and Suddaby 2006) role with their experience and capacity that crossed the political, business, and philanthropic boundaries and/or the US–Japan boundaries. This section offers an overview of the background of these key actors, showing why they are considered to be boundary-bridging actors. I classify them into two groups that are not necessarily mutually exclusive: one group furthered Japanese philanthropy beyond the US–Japan boundary, and the other was primarily based in Japan to convene the philanthropic and corporate circles and develop the Japanese concept of firansoropii.

The Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE) and the Keidanren (Japan Business Federation) were among the key actors who bridged the national boundaries. Tadashi Yamamoto, the chief architect of developing US–Japan relations through philanthropy, found JCIE in 1970. Yamamoto’s role in boundary bridging across both the US–Japan divide and diverse fields originated from his own background. After earning an MBA in the United States and a stint at Shin-Etsu Chemical Company in Japan, he organized the Shimoda Conference, a forum for unofficial policy discussions involving influential intellectuals and politicians from the United States and Japan, in 1967. Table 1 and the following sections illustrate that under Yamamoto’s leadership, JCIE catalyzed the introduction of American philanthropy to Japan through a variety of initiatives, such as overseas missions, international symposia, and publications translated from English into Japanese.

Although populated with Japanese corporate members in Japan, Keidanren’s impact on international cooperation still was widely acknowledged (Yamamoto 1986). As detailed below, JCIE and Keidanren, as well as other associations, organized North American missions and seminars to educate corporate and philanthropic leaders about philanthropy. Keidanren, and the Japan Foundation, a special legal entity supervised by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a Japanese government’s initial endowment of 78 billion yen (approximately $720 million)Footnote 9, became fundraising intermediaries for Japanese companies. When the US–Japan trade conflict became pronounced in 1970, the two organizations coordinated fundraising efforts among Japanese corporations to support American non-profits (Bestor 2002). Due to the Keidanren’s strong ties to the governmentFootnote 10, the Japanese government granted the Keidanren special provisions to allow tax-deductible gifts from its member corporations and re-direct the funds to the U.S. non-profit organizationsFootnote 11. This unique “Keidanren method” (Fusano 1986) facilitated significant gifts from Japanese corporations, such as a $1 million gift to the Gallery of Oriental Art at the Smithsonian Institution in 1980 (Yamamoto 1986).

The main Japanese philanthropic actors spanning philanthropic and corporate circles included the Toyota Foundation, Japan Association of Charitable Organizations (JACO), and Japan Philanthropic Association (JPA). While their core activities and mission are firmly philanthropic, the corporate element has been integrated into their internal structure in such forms as provision of funding, corporate professionals serving as executive leadership (JACO) and on the board (Toyota Foundation), and affiliating corporations as members (JPA). The Toyota Foundation, for instance, was established in 1974 as a corporate foundation of the Toyota Motor Corporation; however, it acted as if it were a private foundation under the leadership of its first managing director Yujiro Hayashi, in conjunction with chairman Eiji Toyoda from the founding family of the corporation. The Toyota Foundation hired philanthropy professionals exclusively, rather than staff from corporate headquarters, and laid out programs that were completely unrelated to the corporate business (Y. Yamaoka, personal communication, July 6, 11, 18, 22, and 27, 2016). As such, the Toyota Foundation championed numerous internal and external initiatives, in which the American concept of philanthropy was first explored and the Japanese concept of philanthropy later emerged as firansoropii (Hayashi and Imada 1999; Hayashi and Yamaoka 1984, 1993). The Toyota Foundation reached out to the corporate circle and introduced the new concept of firansoropii to corporate officers, as well as philanthropic practitioners, in monthly discussions, which then Toyota Foundation’s program director, Yamaoka, reported in JACO’s monthly magazines from 1988 to 1991.

Advancing Japanese Philanthropy Between the United States and Japan

Organized efforts to advance Japanese philanthropy emerged early in the 1970s in the international arena. In the 1970s, Keidanren began systematically coordinating Japanese corporate giving in the United States as a major part of its work (Katsumata 2006). This resulted in mega-gifts from Japanese corporations to American leading universities, such as the Mitsubishi Group’s $1 million gift to Harvard Law School in 1973. The major effort advancing Japanese philanthropy at large was proclaimed by JCIE’s 1974 North America study mission. The mission was composed of both philanthropic leaders and economic leaders of Japan. As part of its International Philanthropy Project, JCIE sponsored the 1974 mission in partnership with Keidanren, Keizai Doyukai (Japan Association of Corporate Executives), JACO, and Trust Companies Association of Japan (Yamamoto et al. 1991). Soon after, the Toyota Foundation’s first Managing Director, Yujiro Hayashi, visited private foundations in the United StatesFootnote 12 (Toyota Foundation; Yamaoka 2015).

The involvement of corporate leaders in the philanthropy mission and symposia naturally invoked a strong interest among businesspeople in corporate philanthropy of not only Japan-based, but also US-based Japanese companies. Japanese philanthropic leaders (Deguchi 1993; Hayashi and Imada 1999; Katsumata 2006; Shimada 1993) point to a mutual influence between US-based and Japan-based philanthropy by Japanese corporations during the 1980s and onward. Corporate philanthropy by US-based offices was aligned with Japan headquarters’ because the headquarters in most Japanese companies consolidated ultimate decision-making for their corporate giving (Deguchi in Shimada 1993). Executives of Japanese corporate foundations in the United States (e.g., Delwin Roy, the founding President and CEO of the Hitachi Foundation) also highlighted their strong ties to the parent companies in Japan (Deguchi 1993). Accordingly, Keidanren and other business associations extended their influence to Japanese corporate philanthropy in the United States. Major initiatives included the 1988 formation of the Council for Better Investment in the United States (CBIUS) by Keidanren. Japan Overseas Enterprises Association (JOEA) compiled a proposal for Japanese corporations, Community Relations: Being a Good Corporate Citizen of Local Communities in the United States (Japan Overseas Enterprise Association 1988). In addition, the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry in New York and independent consultants (e.g., Craig Smith of Digital Partners) offered their assistance to US-based Japanese corporations (M. Deguchi, personal communication, December 8, 2015).

Around the same time, Japanese corporate executives, who encountered American philanthropy during their tenure at US-based offices, began introducing ideas and practices of American corporate philanthropy to Japanese audience upon their return to Japan. Kazuo Watanabe of Mitsubishi Electric and Toshio Matsuoka of PHP America were among those. Citing his experience in receiving warm welcome from local people in Durham, NC, Watanabe urged other Japanese corporate managers to realize corporate philanthropy pertains to not mere financial giving, but more importantly, becoming part of the local community (Watanabe 1997). His observation of John Hancock Outreach Programs taught Matsuoka that many American companies focused their giving on supporting non-profits and programs in the community where the companies operate (T. Matsuoka, personal communication, December 8, 2015). In 1988 proposal of JOEA for which he served as the chair of its international community relations committee, Matsuoka stressed the importance of “localization” over “globalization.” In sum, Watanabe, Matsuoka, and other Japanese corporate executives oversea learned that philanthropy should be rooted in a local community; Japanese corporations oversea must give the highest priority to becoming a good local corporate citizen rather than seeking profits.

Advancing Philanthropy and Corporate Philanthropy Together in Japan

JCIE’s mission and Yujiro Hayashi’s trip to the United States in 1974 yielded critical field-configuring events that catalyzed collective efforts to advance philanthropy in Japan. An influential event was JCIE’s International Philanthropy Project Symposium in 1975. As the largest international conference on philanthropy ever held in Japan, JCIE’s 1975 international symposium invited high-profile philanthropic professionals from the United States and Europe (e.g., president of the Ford Foundation) and introduced American corporate and foundation giving to a Japanese audience (Yamamoto 1986).

Another critical event was Firansoropii Fohramu (“Forum on Philanthropy”), which entailed the three projects that Toyota Foundation supported (Yamaoka 2015). As witnessed in the first and second projects of Toyota Foundation’s Firansoropii Fohramu (“The Philosophy and Social Function of the Grant-Making Activities of Private Foundations in Japan” in 1982 and “The Origins of Japanese Philanthropy: Private Nonprofit Activity in the Taisho Era” in 1984), field-configuring efforts during the 1980s shifted focus from learning about American philanthropy to exploring Japanese traditions and original concepts of philanthropy. Further, the third project of Firansoropii Fohramu, “A Study of Japanese Corporate Philanthropy,” invited corporate leaders to meetings to discuss corporate philanthropy. Still, the reports published in JACO’s monthly journals from February 1987 to August 1991 underline that the main focus of Firansoropii Fohramu remained the same, tradition and meaning of Japanese philanthropy. While the first six meetings of the third project of Firansoropii Fohramu covered practical information about corporate philanthropy, the project mainly introduced Japanese philanthropic traditions to corporate professionals and urged the audience to ponder the concept of firansoropii. In this way, philanthropic leaders in Japan were able to share the concept of Japanese philanthropy with corporate leaders, promoting the coevolution of Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy. During the 1980s, philanthropic and economic leaders, such as JCIE, JACO, Keidanren, and the Hitachi Research Institute (a think-tank established by Hitachi, Ltd. in 1973), as well as former executives of US-based Japanese companies, continued to instill private and corporate philanthropies in Japanese audience via symposia, seminars, and publications.

Deguchi (M. Deguchi, personal communication, December 8, 2015, June 21, 2016) underlines the pivotal role of these collective, sector-spanning initiatives that linked the philanthropic circle (e.g., Noboru Hayase, CEO of the Osaka Voluntary Action Center) and the corporate circle (e.g., Natsuaki Fusano, Managing Director of Keidanren, and Masami Tashiro, the first manager of Keidanren’s Corporate Philanthropy Division) in developing Japanese philanthropy in society at large with mutualistic effects on both communities. One symbolic event was the creation of the One-Percent Club in 1990 in Tokyo. While initially established within Keidanren, the One-Percent Club encourages not only its corporate members but also individual members to contribute 1% of their recurring profits or their disposable income (in the case of individuals) each year (Keidanren n.d.).

Mutualistic Effects on Japanese Philanthropy and Corporate Philanthropy

Effects on Japanese Philanthropy: A New Japanese Concept of Philanthropy “Firansoropii”

Exploring the New Symbolic Concept for Japanese Philanthropy

Archival documents and my personal interviews suggest that, contrary to Western critics’ perceptions, Japanese thought leaders well grasped the spirit of American philanthropy, such as the concepts of the public good (Payton 1988) and pluralistic views (Daly 2012). Tadashi Yamamoto at JCIE, for instance, had been enlightened about the public and altruistic nature of American philanthropy from JCIE’s projects beginning in 1973, but his understanding was deepened when he met John D. Rockefeller 3rd in Tokyo on October 23, 1974. Rockefeller said to him, “Philanthropy; it’s care, caring for others above you” (Japan Association of Charitable Organizations 2000). Yujiro Hayashi at the Toyota Foundation wrote in the Foundation 1975 annual report that a philanthropic foundation should exist for the public purpose, as should the Toyota Foundation, even though it was a corporate foundation. In 1976, Hayashi put forth the idea that the Toyota Foundation’s role was to promote a pluralistic society in Japan as American foundations did in the United States. Notwithstanding, such recognition of the concept of philanthropy among the Japanese remained within the philanthropic community during the 1970s. It was not until after the late 1980s that firansoropii became known to those outside the professional circle in Japan (M. Deguchi, personal communication, December 8, 2015).

The most significant effect of the Firansoropii Fohramu and other initiatives during the 1980s and after was the emergence of the term firansoropii, a Japanese katakana word used to transcribe the English word philanthropy. My personal interviews with philanthropic leaders (e.g., Yamaoka, a core member of Firansoropii Fohramu) and their publications (Hayashi and Imada 1999; Hayashi and Yamaoka 1993) underscore the purposive manner in which they chose a new katakana word firansoropii, instead of the Japanese traditional synonyms, such as jizen, tokushi-katsudo, or hakuai, to diffuse the Japanese concept of philanthropy in Japanese society. They thought that jizen emphasized a vertical relationship between givers and recipients (Kawazoe and Yamaoka 1987), implying that relief activities were offered by those in a privileged position to those in need. In other words, Jizen was lacking meaning of “equality,” “voluntary,” and “the public,” the very ideas that they interpreted as the core principles of American philanthropy. Becoming part of the global community, Japan would acutely need a true understanding of “the public” and respect for pluralism and shared values among the members of society at large rather than a tight-knit neighborhood (Hayashi and Yamaoka 1993). Hayashi states, “Because a clearly defined concept of self-identity has still not been instilled in the citizenry and in many instances the concept of ‘public’ still refers to a specific, limited group, achieving pluralism in Japan is crucial to the growth of Japanese society” (Toyota Foundation 1976, p. 8). The new Japanese concept firansoropii, as derived from the American concept philanthropy, could reinvigorate the innovative spirit of civil society.

Instilling the New Concept Firansoropii

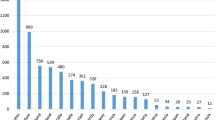

Institutionalists theorize that media and publications, as well as seminars and symposia, are primary carriers that spread new ideas and practices throughout society (Scott 2008). Following this implication, I looked to publication trends on philanthropy or cognate topics with interview data and records retrieved from National Diet Library Online Public Access Catalog and Scholarly and Academic Information Navigator in order to grasp how and to what extent firansoropii was instilled in Japan from the 1970s–1990s. Particular attention was paid to how the word firansoropii appeared in the publication title or subtitle and who was the main audience.

The findings from my review suggest that publications about philanthropy were limited in the 1970s and primarily targeted professionals who engaged in philanthropy. Examples include the Japanese versions of Organized Philanthropy in the United States by Datus Smith of the Council on Foundations, and Corporate Philanthropy in the United States by James Harris of Corporate Contributions Council reports that JCIE first used to educate its 1974 mission participants and later disseminated to other Japanese audiences. (H. Katsumata, personal communication, November 27, 2015). The first appearance of the Japanese word firansoropii in an article title was in the February 1975 issue of Keidanren’s monthly magazine, Keidanren Geppou: Takamaru Firansoropii no Igi to Katsudo (Growing Value and Activities of Philanthropy). Nonetheless, as this article aimed at foundation and corporate giving professionals, one can assume that firansoropii was an almost unknown concept among the Japanese public.

As Deguchi (M. Deguchi, personal communication, December 8, 2015, June, 21, July 13, 14 and 25, 2016) suggests, the late 1980s and after saw a rapid increase in the number of publications explicitly referring to firansoropii. NDL-OPAC records offer evidence of this, showing a significant increase in the number of Japanese publications using firansoropii in their titles/subtitles from the 1980s to 1990s (8, 3, and 129 during 1970, 1980Footnote 13, and 1990s, respectively)Footnote 14. Main target audience was also shifted from professionals to the general public. The earliest books for the general public, which used the Japanese word firansoropii along with Japanese synonyms tokushi-jigyo (篤志事業) in the main body, are Hayashi and Yamaoka’ Nihon-no Zaidan (Foundations in Japan) (1984) and Hayashi’s Japanese translated version of Willard Nielsen’s book on American foundations (Yamaoka 2015). NDL-OPAC data confirm Kawazoe and Yamaoka’s 1987 book Nihon no Kigyoka to Syakai Bunka Jigyo: Taisho-ki no Firansoropii as the first Japanese-written book for a general audience with a subtitle using firansoropii. The 1990s saw an increasing number of books published with firansoropii in the titles, including Honma (1993), Hayashi and Yamaoka (1993), and Deguchi (1993) as well as the Japanese edition of London’s Japanese Corporate Philanthropy.

Newspapers reach even wider audiences than do books, and thus the appearance in major Japanese newspapers is a reasonable measure to understand how much firansoropii was instilled in Japanese society. The review of Kawazoe and Yamaoka’s 1987 book in Nikkei Newspaper appears to be the first appearance of firansoropii in a major Japanese newspaper (Yamaoka 2015). Sankei Newspaper published Deguchi’s weekly column titled firansoropii for over two years from January 1991 to March 1993 (M. Deguchi, personal communication, July 13, 2016). Hence, the early1990s seem to be the turning point for the recognition of firansoropii in Japanese society at large. This is supported by Osugi’s findings (2012) that the word firansoropii first appeared in Japanese language dictionaries in the 1994 edition of Sanseido’s dictionary for katakana (Japanese words used for transcription of foreign language words), followed by the 1998 edition of the most authoritative Japanese–Japanese dictionary, Kojien.

Effects on Japanese Corporate Philanthropy: Changing Ideas and Practices for Domestic and International Corporate Philanthropy

As the interview and bibliographic data show, the Japanese corporate community was exposed to the new concept of firansoropii as early as the 1970s. Because of this, firansoropii was often misinterpreted as corporate giving in the early days (Hayashi and Yamaoka 1993). The 1994 edition of Sanseido’s katakana dictionary and the 1998 edition of Kojien still defined firansoropii as socially benefitting activities primarily undertaken by business corporations (Osugi 2012).

However, this does not mean that Japanese corporate philanthropic activities remained unchanged from the early days. Existing records reveal that the field-spanning activities (e.g., Toyota Foundation’s Firansoropii Fohramu, JCIE, and Keidanren’s initiatives) as well as actors (e.g., Watanabe and Matsuoka) instilled new ideas and practices of kigyo firansoropii (corporate philanthropy) in corporate officers. Studying Japanese philanthropic tradition, the philanthropic circle (Kawazoe and Yamaoka 1987) and the corporate circle (Aoki 2004) rediscovered that the spirit of corporate citizenship and philanthropy had been part of Japanese business philosophy to care about their communities. Aoki (2004) asserts that there were fundamental differences between American and Japanese corporate philanthropy. According to him, the primary concern of American corporations in the first half of the 20th century was whether or not philanthropy was justifiable for for-profit entities, whose primary responsibility was to serve stakeholders’ interests in pursuing profits. Japanese corporations, however, had never agonized over the issue of philanthropy as a legitimate corporate practice. In fact, Japanese businesspeople were concerned about whether making a profit itself was ethical; instead, profits should be shared among people involved in the business, including employees. Indeed, unlike Western critics’ reasoning that charitable tax deductibility was imperative for cultivating philanthropy in Japan (Epstein 1991; London 1990), some corporate foundations, such as the Toyota Foundation, supported the humanities and social sciences, thus foregoing the tax benefits awarded under the Japanese government’s ERC system.

This very philosophy was revisited during the soul-searching of Japanese corporate and philanthropic leaders during the 1970s–1990s. A 1989 publication by the Japan Institute for Social and Economic Affairs, a public affairs center of Keidanren (Flaherty’s article bilingually translated both into Japanese and English, America Ni Ikiru Nihon Kigyo [The Japanese Corporation in the United States]), shows that Keidanren initially promoted philanthropy as a strategic tool to mitigate trade conflicts. However, a document put forth by Kyoko Shimada (2001), then Chairperson of Keidanren’s subcommittee (Changing Society & Corporate Philanthropy), shows that Keidanren had begun serious dialogues about what corporate philanthropy should be in the 1990s. Keidanren defined corporate philanthropy as “to notice and to voluntarily take action for the urgent issues of the society, to which corporate resources are donated without seeking direct pay-off.” Keidanren’s 1991 Charter for Good Corporate Behavior listed philanthropy as one of the seven principles that Japanese corporations should abide by as socially responsible members (Keidanren 1991). Results from the Keidanren’s 1993 survey (Keidanren 1994) about corporate philanthropy show that 85.9% of Japanese corporations engaged in philanthropy out of “responsibility of a citizen,” by far outpacing other reasons [“to improve company image” (38.9%), “to redistribute profits to society” (36.6%), and “to strengthen a tie with society” (27.1%)].

The new ideas and practices of corporate philanthropy diffused simultaneously through US-based Japanese corporations as well. Being asked to contribute particularly in the geographical areas into which they were pouring the greatest amount of direct foreign investments, Japanese corporations shifted their support from leading universities and arts organizations to community-based projects. Around this time, the concept of good corporate citizenship emerged in both the United States and Japan. In 1989, Keidanren reorganized CBIUSA as the Council for Better Corporate Citizenship, indicating that the focus of Japanese corporate philanthropy in the United States would shift from the 1970s mega-giving approach to more community-based projects as local corporate citizens (Katsumata 2006). Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), the 100 % funded trade association of Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, published Kigyo Firansoropii no Jidai (The Era of Corporate Philanthropy) (Nagasaka 1991), in which the term good corporate citizenship appears repeatedly.

As stressed by Japanese philanthropic scholars (Aoki 2004), the idea of good corporate citizenship was hardly new in the history of Japanese businesses. However, what was striking this time was the way Japanese corporations integrated this philosophy of corporate citizenship into their business practices. As noted previously, the JETRO 1995 survey (Japan External Trade Organization 1995) showed a significant shift in US-based Japanese corporate giving away from mega-giving to America’s leading universities and arts organization. Conversely, in the 1990s, the majority (68%) of Japanese corporate gifts went to local and community development programs, whereas only 21 and 22% went to universities and arts, respectively. Their support at the local level was not only to demonstrate a sense of their own civic duty but also to contribute to their company’s success.

Concluding Thoughts

This study analyzed the process by which the concept and activities of Japanese philanthropy and corporate philanthropy were tested, refined, and legitimized from the 1970s through the 1990s. Through the lens of agent-based institutionalism and structuration, this study chronicles milestone events bridging two countries (Japan and the United States) and sectors (philanthropic and corporate) to reveal how Japanese philanthropic and corporate leaders developed firansoropii—the new concept adopted from American philanthropy—and how firansoropii was diffused and institutionalized. Also, this study assures that involvement of the prominent “boundary-bridging” actors from both philanthropic and corporate circles was vital in legitimizing firansoropii and institutionalizing this emerging concept. As such, this study not only contributes to a growing scholarly effort about conceptualization of philanthropy (Daly 2012; Sulek 2010), but also complements this line of research by showing the complex, microlevel process of conceptualizing philanthropy and impacts of sociocultural factors in this process. I hope that this study opens a meaningful dialogue for better understanding not only Japanese philanthropy but also sociocultural factors underlying unique meaning of philanthropy in different national and cultural contexts.

Notes

It should be noted that recent studies by Japan Fundraising Association estimate a vastly greater amount of individual giving by adding revenues from other sources, such as donations to religious organizations and membership fees, which are generally not included in other statistics.

I consulted with Marty Sulek, the author of the article “On the modern meaning of philanthropy” (Sulek 2010), about this matter.

Despite many similarities between kanjin and Western capital campaign fundraising, English-language references to kanjin are extremely rare. See Lohmann (1995).

Katsumata (2006) highlights the “public” nature of Akita Kannon-ko. In contrast to earlier “mutual aid” funds that benefited only those in a limited geographic area or circle of relatives, the Akita Kanon-ko received contributions from the general public in the region, and the funds were distributed to those in need regardless of their clan or geographic location.

Kimura (2006) concludes that given the Morimura’s network of contact in the United States, he was likely to have become aware of activities by American foundations, such as the Carnegie Corporation and the Rockefeller Foundation, at an early stage.

Part of the Civil Code was revised when Japan’s new constitution was promulgated in 1946 and implemented in 1947. However, the section concerning koeki hojin remained unchanged. Article 89 forbade public funds to be directed to private organizations not under public control, in order to avoid the re-emergence of the strong national regulation imposed on private organizations during the prewar and war years (Yamaoka 1998).

Other Japanese terms, such as hakuai (博愛), jiai (慈愛), and jihi-shin (慈悲心), are often regarded as synonymous with philanthropy, yet as a wider interpretation, denoting a benevolence or a love of humanity. For instance, Kimura (2006) explains that hakuaishugi (博愛主義) means “the principle that all humans should love each other equally, abandoning individual selfishness, rational prejudices, national interests, and religious or ideological partnership in favor of promoting the welfare of all humanity” (p. 279). However, many philanthropic leaders, such as Kawazoe and Yamaoka (1987), concluded that hakuai was too abstract and possibly not the best synonym for the American concept of philanthropy. I would like to express my gratitude to reviewers, who encouraged me to explore these various concepts referring to Japanese philanthropic tradition.

It should be noted that this mindset did not reflect the actual provision of social welfare services from the Japanese government. Japanese government expenditures for social welfare were lower in comparison with other developed countries (see Haddad 2010). I would like to thank a reviewer for this suggestion.

The Japan Foundation (The Japan Foundation 1988) enabled “virtually all large Japanese corporate grants for museums, research institutes, and universities in the United States” (p. 51).

A large portion of Keidanren’s donations from Japan’s corporate giants were automatically allocated to the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Japan’s largest and longest governing political party. This close tie to LDP has granted Keidanren enormous power as a liaison between large business corporations and the government on policy matters (Allinson 1987).

Non-profits seeking major Japanese corporate funds were required to first obtain an endorsement from the Keidanren. Once overall financial strength and current economic performance were evaluated, Keidanren officials made recommendations to specific industries and companies to contribute specific amounts to the applicant nonprofit. Given the Keidanren’s list of potential corporate donors made up of some 30 industry groups and 300 companies, the applying non-profits finally would contact the listed companies (Fusano 1986).

Planning for Hayashi’s trip to the United States was assisted by JCIE’s Tadashi Yamamoto and Hideko Katsumata (Y. Yamaoka, personal communication, July 27, 2016).

Interestingly, the records of both NDL and CiNii show there were no publications with firansoropii in the title or subtitle during 1979 and 1986.

Osugi (2011) found 83 publications with the Japanese synonym, jizen-jigyo, and 5186 publications with shakai-jigyo, in their titles as of September 2010. The current study examines institutionalization of the Japanese translation of the American word philanthropy, and thus does not include the studies that Osugi reviewed. My review also did not include the publications using other synonyms for corporate philanthropy, kigyo-shimin (corporate citizenship) as my focus was to investigate institutionalization of the concept firansoropii.

References

Allinson, G. D. (1987). Japan’s Keidanren and its new leadership. Pacific Affairs, 60(3), 385–407.

Aoki, T. (2004). Nihon-gata kigyo no shakai koken: Shonindo no kokoro wo mitsumeru (Japanese corporate philanthropy: In search of its root, shonindo in the Edo Period). Tokyo: Toho Shobo.

Barley, S. R., & Tolbert, P. S. (1997). Institutionalization and structuration: Studying the links between action and institution. Organization Studies, 18(1), 93–117.

Bestor, V. L. (2002). Toward a cultural biography of civil society in Japan. In R. Goodman (Ed.), Family and social policy in Japan: Anthropological approaches (pp. 29–53). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bestor, V. L. (2005). The Rockefeller blueprint for postwar US-Japanese cultural relations and the evolution of Japan’s civil sector. In S. Hewa & D. Stapleton (Eds.), Globalization, philanthropy, and civil society: Toward a new political culture in the Twenty-First Century (p. 73). Springer: New York.

Burlingame, D., & Young, D. R. (1996). Corporate philanthropy at the crossroads. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Cabinet Office. (2016). Kihukin no kokusai hikaku (comparative data on giving among Japan, US and UK). NPO Homepage. Retrieved October 6, 2016, from https://www.npo-homepage.go.jp/kifu/kifu-shirou/kifu-hikaku

Cho, M., & Kelly, K. S. (2014). Corporate donor–charitable organization partners: A coorientation study of relationship types. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(4), 693–715.

Chuo Mitsui Trust and Banking Company. (2011). Waga kuni kihu doko ni tsuite (Giving trend in Japan) (No. 74). Tokyo, Japan: The Chuo Mitsui Trust and Banking Company.

Cramer, D. (1974). Another million from Japan. News | The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved April 10, 2016, from http://www.thecrimson.com/article/1974/1/18/another-million-from-japan-pharvard-received/

Daly, S. (2012). Philanthropy as an essentially contested concept. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 23(3), 535–557.

Deguchi, M. (1993). Firansoropii: Kigyo to hito no syakaikoken (Philanthropy: Corporate and individual giving to society). Tokyo: Maruzen.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Einolf, C. J. (2016). Cross-national differences in charitable giving in the west and the world. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 1–20.

Epstein, S. (1991). Buying the American mind: Japan’s quest for U.S. ideas in science, economic policy and the schools. Washington, D.C.: Center for Public Integrity.

Flaherty, S. (1989). Amerika ni ikiru nihon no kigyo: Kigyo kihu no tetsubgaku (The Japanese corporation in the United States: Philosophy of corporate philanthropy). Tokyo: Japan Institute for Social and Economic Affairs.

Fusano, N. (1986). Corporate giving in Japan and Keidanren’s role. The role of philanthropy in international cooperation (Report on the JCIE 15th Anniversary International Symposium) (pp. 6–7). Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange.

Gautier, A., & Pache, A. C. (2013). Research on corporate philanthropy: A review and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(3), 343–369.

Giddens, A. (1979). Central problems in social theory: Action, structure, and contradiction in social analysis (Vol. 241). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Greenwood, R., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutional entrepreneurship in mature fields: The big five accounting firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 27–48.

Haddad, M. A. (2010). A state-in-society approach to the nonprofit sector: Welfare services in Japan. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 22(1), 26–47.

Hayashi, Y., & Imada, M. (1999). Firansoropii no shiso: Enu pii oh to borantia (The concept of philanthropy: Nonprofits and volunteering). Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyoron Sya.

Hayashi, Y., & Yamaoka, Y. (1984). Nihon no zaidan: Sono keifu to tenbou (Foundations in Japan). Tokyo: Chuo-Koron Sha.

Hayashi, Y., & Yamaoka, Y. (1993). Firansoropii to syakai: Sono nihonteki kadai (Philanthropy and society). Tokyo: Diamond Publisher.

Honma, M. (1993). Firansoropii no syakai keizaigaku (Socioeconomics of philanthropy). Tokyo: Toyo Keizai Shimpo Sya.

Imada, M. (2003). The voluntary response to the Hanshin Awaji earthquake: A trigger for the development of the voluntary and non-profit sector in Japan. In S. P. Osborne (Ed.), The voluntary and non-profit sector in Japan: The challenge of change (pp. 40–50). New York, NY: Rountledge Curzon.

Imada, M. (2006). Nihon no enu pii oh shi (A history of NPOs in Japan). Tokyo: Gyosei.

Iriye, A. (2006). The role of philanthropy and civil society in US foreign relations. In T. Yamamoto, A. Iriye, & M. Iokibe (Eds.), Philanthropy and reconciliation: Rebuilding postwar US-Japan relation (pp. 37–60). Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange.

Ishida, Y., & Okuyama, N. (2015). Local charitable giving and civil society organizations in Japan. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(4), 1164–1188.

Japan External Trade Organization. (1995). Survey of corporate philanthropy at Japanese-affiliated operations in the United States. New York: JETRO.

Japan Overseas Enterprise Association. (1988). Komyunitii reraishonzu: Beikoku chiiki shakai no yoki kigyo shimin to shite (Community relations: Being a good corporate citizen of local communities in the United States). Tokyo, Japan: Japan Overseas Enterprise Association.

Jepperson, R. L. (1991). Institutions, institutional effects, and institutionalism. In P. DiMaggio & W. P. Powell (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (Vol. 6, pp. 143–163). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Johnson, C. (1988). Japan digs deep to win the hearts and minds of America. Business Week.

Katsumata, H. (2006). Japanese philanthropy: Its origins and impact on U.S.-Japan relations. In T. Yamamoto, A. Iriye, & M. Iokibe (Eds.), Philanthropy & reconciliation: Rebuilding postwar U.S.-Japan relations (pp. 313–344). Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange.

Kawazoe, N., & Yamaoka, Y. (1987). Nihon no kigyoka to syakaibunkajigyo: Taisyo ki no firansoropii (Japanese industrialists and philanthropy). Tokyo: Toyo Keizai Shimpo Sya.

Keidanren. (1991). 1991 Keidanren charter for good corporate behavior. Retrieved August 1, 2016, from http://www.keidanren.or.jp/english/speech/spe001/s01001/s01a.html

Keidanren. (1994). Survey concerning corporate philanthropic activities (Fiscal Year 1993). Tokyo: Kendanren.

Keidanren. (n.d.). Keidanren: Corporate responsibility and community spirit. Retrieved July 17, 2016, from https://www.keidanren.or.jp/english/profile/pro007/pr07001.html

Kimura, M. (2006). U.S.-Japan business networks and prewar philanthropy: Implications for postwar U.S.-Japan relations. In T. Yamamoto, A. Iriye, & M. Iokibe (Eds.), Philanthropy & reconciliation: Rebuilding postwar U.S.-Japan relations (pp. 280–312). Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange.

King, E. K. (1991). Omnibus trade bill of 1988: Super 301 and its effects on the multilateral trade system under the GATT. University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Business Law, 12, 245.

Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710.

Lee, T. W. (1999). Using qualitative methods in organizational research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

Lohmann, R. A. (1995). Buddhist commons and the question of a third sector in Asia. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 6(2), 140–158.

London, N. R. (1990). Japanese corporate philanthropy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2010). Designing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Marx, J. D. (1999). Corporate philanthropy: What is the strategy? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 28(2), 185–198.

Matsubara, A., & Todoroki, H. (2003). Japan’s “culture of giving” and nonprofit organizations. Tokyo: Coalition for Legislation to Support Citizens’ Organizations.

Nagasaka, H. (1991). Kigyo firansoropii no jidai: Yoki kigyo shimin eno michi (The era of corporate philanthropy). JETRO Books (Vol. 4). Tokyo: Japan External Trade Organization.

Onishi, T. (2007). Japanese fundraising: A comparative study of the United States and Japan. International Journal of Educational Advancement, 7(3), 205–225.

Osugi, Y. (2011). Nihon: Firansoropii kenkyu ni okeru genjyo bunseki to rekishi kenkyu no kadai (Japan : Problems of present and historical research into philanthropy in Japan). Ohara syakai mondai kenkyu-jyo zassi, 628, 17–23.

Osugi, Y. (2012). Nihon ni okeru firansoropii: Beikoku wo chushin to sita kokusaitekishiten, rekishitekishiten (Philanthropy in Japan: From the viewpoint of the United States of America, Japanese history and welfare). Keizai-gaku ron syu, 78(1), 105–128.

Payton, R. L. (1988). Philanthropy: Voluntary action for the public good. New York, NY: American Council on Education.

Payton, R. L., & Moody, M. P. (2008). Understanding philanthropy: Its meaning and mission. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Reynolds, W. (1973). Japanese give university $1 million: Second large donation. News | The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved April 10, 2016, from http://www.thecrimson.com/article/1973/9/21/japanese-give-university-1-million-pthe/

Schumer, F. (1973). Japanese give $1 million to Harvard. News | The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved April 10, 2016, from http://www.thecrimson.com/article/1973/10/13/japanese-give-1-million-to-harvard/

Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Shimada, H. (Ed.). (1993). Kaika suru firansoropii (Blooming philanthropy). Tokyo: TBS-BRITANNICA.

Shimada, K. (2001). Overview of the Japanese corporate philanthropy in 1990’s (2001-07). Japan: KEIDANREN. Retrieved July 9, 2016, from https://www.keidanren.or.jp/japanese/profile/1p-club/book200107e/prologue.html

Sulek, M. (2010). On the modern meaning of philanthropy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(2), 193–212.

Teltsch, K. (1989). Japanese increase donations in the U.S. The New York Times. Retrieved March 30, 2016, from http://www.nytimes.com/1989/11/12/us/japanese-increase-donations-in-us.html

The Japan Association of Charitable Organizations. (2000). A dialogue on philanthropy 1: The 30 years of JCIE’s contributions and prospects. Koueki Houjin, 2–13.

The Japan Association of Charitable Organizations. Koueki Houjin, November, 1987, February–June 1988, May–November, 1990, January–August, 1991, February, 1993. Tokyo: The Japan Association of Charitable Organizations

The Japan Foundation. (1988). Annual Report 1987. Tokyo: The Japan Foundation.

The Taft Group. (1989). Directory of international corporate giving in America. Washington, DC: The Taft Group.

Toyota Foundation. Annual reports for 1975, 1976, 1977, 1978, 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, and 1987. Tokyo: Toyota Foundation

Tucker, M. E. (1998). A view of philanthropy in Japan: Confucian ethics and education. In W. F. Ilchman, S. N. Katz, & E. L. Queen (Eds.), Philanthropy in the world’s traditions (pp. 169–193). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Watanabe, K. (1997, January 20). Nihon gata firansuropii no choryu (The origin of Japanese philanthropy). Retrieved March 18, 2016, from http://www.zenkaiken.jp/httpd/html/kaiho/55.htm

Wiepking, P., & Handy, F. (2016). The Palgrave Handbook of Global Philanthropy. New York: Springer.

Yamamoto, T. (1986). The role of philanthropy in international cooperation: Report in the JCIE 15th Anniversary International Symposium. Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange.

Yamamoto, T., & Amenomori, T. (1989). Japanese private philanthropy in an interdependent world. Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange.

Yamamoto, T., Iriye, A., & Iokibe, M. (2006). Philanthropy and reconciliation; rebuilding postwar US-Japan relations. Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange.

Yamamoto, T., Kamura, H. P., & Katsumata, H. (1991). International philanthropy project of the Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE): A case study. Tokyo: Japan Center for International Exchange.

Yamaoka, Y. (1998). On the history of the nonprofit sector in Japan. In T. Yamamoto (Ed.), the nonprofit sector in Japan (pp. 19–58). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Yamaoka, Y. (2015). A role of Yushiro Hayashi and Toyota Foundation in developing the notion of philanthropy in Japan. Unpublished manuscript.

Yamauchi, N., Matsunaga, Y., & Matsuoka, H. (2004). Statistical portrait of giving and volunteering in the nonprofit satellite accounts. ESRI Discussion Paper Series No.126. Tokyo: Economic and Social Research Institute Cabinet Office.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Masayuki Deguchi, Noboru Hayase, Hideko Katsumata, Toshio Matsuoka, Kuniko Mochimaru, Tetsuya Murakami, Tasuo Ohta, Yuka Osugi, Kohei Suzuki, Yoko Takahashi, and Yoshinori Yamaoka for their invaluable comments on Japanese philanthropy. My deep appreciation also goes to our editors and anonymous reviewers for their guidance and encouragement throughout the revision process, and to Wolfgang Bielefeld, Ruth H. DeHoog, Leslie Lenkowsky, Kevin C. Robbins, and Marty Sulek for their insights into philanthropy and helpful comments on this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Onishi, T. Institutionalizing Japanese Philanthropy Beyond National and Sectoral Borders: Coevolution of Philanthropy and Corporate Philanthropy from the 1970s to 1990s. Voluntas 28, 697–720 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9809-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9809-x