Abstract

Literature describing the social change efforts of direct social service nonprofits focuses primarily on their political advocacy role or the ways in which practitioners in organizations address individual service user needs. To elicit a more in-depth understanding of the varying ways that these nonprofits promote social change, this research builds off of the innovation literature in nonprofits. It presents a model of the typology of social innovations based on the empirical findings from survey data from a random sample (n = 241) and interview data (n = 31) of direct social service nonprofits in Alberta, Canada. Exploratory principal factor analysis was used to uncover the underlying structure of the varying types of social innovations undertaken by direct service nonprofits. Results support a three-factor model including socially transformative, product, and process-related social innovations. The qualitative findings provide a conceptual map of the varied foci of social change efforts.

Résumé

Les publications décrivant les efforts de changement social des organisations à but non lucratif de services sociaux directs portent principalement sur leur rôle de sensibilisation politique ou la façon dont les intervenants de ces organisations répondent aux besoins des utilisateurs en termes de services individuels. Pour obtenir une compréhension plus approfondie des différentes façons dont ces organisations à but non lucratif promeuvent le changement social, ces recherches s’appuient sur des publications innovantes concernant ces organisations. Elles présentent un modèle de la typologie des innovations sociales basées sur des résultats empiriques issus de données de l’enquête auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire (n = 241) et des données d’entretiens (n = 31) d’organisations à but non lucratif de services sociaux directs en Alberta, au Canada. Une analyse factorielle exploratoire principale a été utilisée afin de découvrir la structure sous-jacente des différents types d’innovations sociales menées par les organisations à but non lucratif de services directs. Les résultats confirment un modèle à trois facteurs, notamment des innovations sociales visant à la transformation sociale liées aux produits et aux processus. Les résultats qualitatifs fournissent une carte conceptuelle des foyers variés des efforts de changement social.

Zusammenfassung

Die Literatur, die die Bemühungen zum sozialen Wandel seitens gemeinnütziger Organisationen, die direkte Sozialleistungen anbieten, beschreibt, konzentriert sich hauptsächlich auf deren Rolle als Vertreter politischer Interessen oder auf die Art und Weise, in der Praktiker in Organisationen auf die Bedürfnisse einzelner Leistungsempfänger eingehen. Zur Vermittlung eines tiefer gehenden Verständnisses der unterschiedlichen Methoden, mit denen diese gemeinnützigen Organisationen einen sozialen Wandel fördern, baut diese Untersuchung auf die Innovationsliteratur gemeinnütziger Organisationen auf. Es wird ein Modell zur Typologie sozialer Innovationen präsentiert, das auf den emprischen Ergebnissen aus Untersuchungsdaten einer Stichprobe (n = 241) und Befragungsdaten (n = 31) von gemeinnützigen Organisationen in Alberta, Kanada, die direkte Sozialleistungen bereitstellen, beruht. Man wandte die exploratorische Hauptfaktorenanalyse an, um die zugrunde liegende Struktur der unterschiedlichen Arten sozialer Innovationen gemeinnütziger Organisationen, die direkte Leistungen anbieten, zu ergründen. Die Ergebnisse unterstützen ein Drei-Faktoren-Modell, das soziale Innovationen im Zusammenhang mit sozialen Transformationen, Produkten und Prozessen einschließt. Die qualitativen Ergebnisse liefern ein Begriffsbild der unterschiedlichen Schwerpunkte bei den Bemühungen zum sozialen Wandel.

Resumen

El material publicado que describe los esfuerzos de cambio social de las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro de servicios sociales directos se centra fundamentalmente en su papel de defensa política o en las formas en las que los profesionales de las organizaciones abordan las necesidades individuales del usuario de servicios. Para obtener una comprensión más profunda de las variadas formas en las que estas organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro promueven el cambio social, la presente investigación se basa en el material publicado sobre innovación en las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro. Presenta un modelo de la tipología de las innovaciones sociales basado en los hallazgos empíricos de datos de encuestas de una muestra aleatoria (n = 241) y datos de entrevistas (n = 31) de organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro de servicios sociales directos en Alberta (Canadá). Se utilizó el análisis factorial exploratorio para descubrir la estructura subyacente de los diversos tipos de innovaciones sociales emprendidas por las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro de servicios sociales directos. Los resultados apoyan un modelo de tres factores que incluye innovaciones sociales relacionadas con productos y procesos socialmente transformadores. Los hallazgos cualitativos proporcionan un mapa conceptual de los diversos enfoques de los esfuerzos a favor del cambio social.

摘要

介绍直接社会服务非营利性组织在社会变革中所作的努力的文献主要关注其政治倡导作用或者该等组织成员在应对个体服务用户需求中所采取的方式。为了更深刻地理解这些非营利性组织在促进社会变革中所采取的各种方式,本文以非营利性组织创新文献为基础进行研究。根据以下资料的实证结果,本文介绍了社会创新类型学模型:对随机样本(数量 = 241)进行调查所获得的数据、对加拿大亚伯达省的直接社会服务非营利性组织的访谈数据(数量 = 31)。使用探索性主要因子分析法揭示直接服务非营利性组织所从事的各种社会创新活动的基础结构。结果为一个三因子模型提供支持,该模型包括社会变革性社会创新、与产品与流程相关的社会创新。定性结果为社会变革工作的不同焦点提供了概念图。

ملخص

تركز الأدبيات التي تصف جهود التغيير الإجتماعي للخدمة الإجتماعية المباشرة لمنظمات غير ربحية في المقام الأول على دورها في الدعوة السياسية أو الطرق التي بها الممارسين في المنظمات يتحدثون عن خدمة إحتياجات المستخدمين الفردية. للحصول على فهم بعمق للطرق المختلفة لهذه المنظمات الغير ربحية في تشجيع التغيير الإجتماعي ، يستند هذا البحث على أدب الإبتكار في المنظمات الغير ربحية. يقدم نموذج لتصنيف الإبتكارات الإجتماعية على أساس النتائج التجريبية من بيانات إستطلاع رأي من عينة عشوائية (ن = 241) وبيانات المقابلات (ن = 31) للخدمة الإجتماعية المباشرة لمنظمات غير ربحية في ألبرتا، كندا. تم استخدام إستكشاف تحليل العوامل الرئيسية للكشف عن البنية الأساسية لأنواع مختلفة من الإبتكارات الإجتماعية التي تقوم بها المنظمات الغير ربحية للخدمة المباشرة. النتائج تدعم نموذج لثلاث عوامل بما يشمل التحول الإجتماعي ٬ المنتجات و الإجراءات المرتبطة بالإبتكارات الإجتماعية. تقدم هذه النتائج النوعية خريطة مفاهيمية لمركز نشاط متنوع لجهود التغيير الإجتماعي.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Locally based nonprofit direct social service organizations (hereon referred to as nonprofits) have taken on increasing responsibility, over the last three decades, in addressing the direct social welfare needs of social service users in many ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ nations (Powell 2007; Salamon 2002). As a result, the role of nonprofits has become increasingly important in both providing services and creating social change to better meet the emerging needs of service users and local communities (Anheier 2009; Shier and Graham 2013). However, within present scholarship there is only minimal investigation into the different ways that exemplifies this social change role.

Social change efforts in direct service nonprofits is broadly defined here as the actions undertaken by organizations to improve the social situation of individuals accessing services and members within the wider community. These efforts can include a range of activities, including direct service efforts, efforts to change socio-cultural perceptions, and actions that seek to change the social welfare system itself.

In conceptualizing this social change role, the dominant stream of literature has mainly investigated the political advocacy role of nonprofits (Child and Gronbjerg 2007; Kimberlin 2010; Mellinger 2014; Mosley and Ros 2011; Schmid et al. 2008). Almog-Bar and Schmid (2014) provide some evidence of this narrow focus in their recent literature review in the meaning and role of advocacy when applied to nonprofits. For instance, they defined advocacy as an effort to change public policy or influence decisions of government, and to protect individual socio-political rights and freedoms (Almog-Bar and Schmid 2014). This perspective begets the question: Is this the only way that these nonprofits create social change?

Current literature suggests that nonprofits can also create social change through the ways in which they interact with service users and engage with the wider community, and through adaptations to internal processes and structures to meet emerging or changing needs (Shier and Graham 2013; Shier et al. 2014). However, a compounding limitation in this scholarship is that the analysis of the social change efforts has tended to rely on descriptive case study analysis of individual organizations or specific service user populations (Boyd and Wilmoth 2006; Shier and Graham 2013; Spergel and Grossman 1997).

To address these omissions in the scholarship, this research presents a model for understanding the multiple foci of direct service nonprofit organization’s social change efforts for their service user populations and within the community more generally. Utilizing a mixed methods study design, this study uses quantitative and qualitative data to answer the research question: In what ways do direct service nonprofits create social change in their local communities and for service users?

Literature Review

Social change can occur in multiple ways, and this study starts with the premise that innovations undertaken by a nonprofit is a novel way of understanding the nonprofits role in social change. The literature describing innovation in and by nonprofits provides a typology to understand the focus of organizational change and the different levels of impact—such as service user, sector, and community levels of impact (Jaskyte and Lee 2006; Netting et al. 2007).

Innovation refers to the ways in which organizations adapt or change as a result of emerging contextual factors within an organization’s external environment and internal demands. These contextual factors include (among others) our economic system of exchange, our political system of laws and policies, our cultural system of values and beliefs, and changing needs of service users (Ife 1996; Mulroy 2004). These contextual factors provide new opportunities or challenges for nonprofits to think about implementing novel approaches to persistent or emergent problems (Jaskyte and Lee 2006). There are multiple forms of innovation—many of which do not have a social change purpose. For example, new inventions, ideas, or technological advancements can be considered innovative. Similarly, there are some innovations within the business realm that aim to generate higher levels of profit, whereas other innovations may have as a goal to pursue a social good (Borzaga and Bodini 2014).

With regard to the place of social change within this innovation scholarship, it has been conceptualized by the term social innovation; it is through social innovations that organizations seek to create social change (Nichols 2006). Following the definition of Pol and Ville (2009), social innovation refers to “any new idea with the potential to improve either the macro-quality of life or the quantity of life,” and macro-quality of life is defined as “the set of valuable options that a group of people has the opportunity to select” (p. 882). In relation to direct service nonprofits—and for this study in particular—the ‘group of people’ refers to the population of people accessing services.

Within the literature on social innovation, there tends to be a reliance on explicitly generalized definitions of the types of efforts that nonprofits (or individual social entrepreneurs as the literature suggests) undertake to create social change. For instance, Alvord et al. (2004) suggest that innovation for social change can be characterized as transformational, economic, or political; defined consecutively as social change that seeks to create community capacity, change economic systems, or to challenge power relationships in society. While these descriptions are useful in providing some context for the foci of nonprofit’s social change efforts, they do not offer sufficient specificity in conceptualizing the manifestation of social change efforts within and by direct service nonprofits. This generalized focus within the literature in its application to direct service nonprofits is problematic for four reasons.

-

(1)

The underlying goals or intentions of new programs and initiatives differ and they result in different social change outcomes at varying levels of practice (Netting et al. 2007).

-

(2)

Social change efforts tend to be subtler than what is suggested in the social entrepreneurship literature, with social innovation happening within existing organizational structures (Grohs et al. 2013).

-

(3)

Direct service nonprofits differ based on the type and extent of new programs and initiatives they pursue (Jaskyte and Lee 2006), suggesting that social change efforts can be targeted at different organizational levels within the organization—such as the operational level, program level, or through engagement with the external environment.

-

(4)

While all nonprofit social service organizations are reactive to factors in their external environment, not every nonprofit social service organization reacts in the same way and/or to the same issues (Jones 2006; Schmid 2004). Some direct service nonprofits might be targeting efforts at issues of negative public perceptions, while others might see the need to address policy limitations to support sustainable social change, and others might be adapting programs to attain better outcomes.

Indeed, some new programs and initiatives are developed by nonprofits to address omissions in service and to meet changing collective service user needs, but little emphasis is placed on changing the social service delivery system itself (Scott 2008). Netting et al. (2007) refer to these as ‘focused’ programs or initiatives, where the social change efforts sought by new programs or initiatives are at the service user level.

There is evidence of this emerging ‘innovativeness’ typology within the social services in current literature. For instance, innovation has been defined in terms of programs and initiatives created to meet changing administrative and technological needs, including fundraising, resource sharing, and technological improvements (Mano 2009), direct practice innovations including implementation of evidence-based practices, changing the procedures utilized in the way services are provided, and adapting methods of interaction or intervention with service users (Murray 2009; Simpson 2009), and program implementation, including new program development to meet changing or emergent client needs and adaptations to the focus of existing programs to attain better outcomes (Prince and Austin 2001; Wood 2007).

Jaskyte and Lee (2006) refer to the three different types of innovative programs or initiatives as administrative, process, and product innovations. We use two of these innovation types in testing the empirical model of social innovation. (1) Process-related innovations can create social change—by creating better outcomes for service users—through adaptations to methods of interaction within organizations and through organizational development processes (Boyd 2011). (2) Product innovations can create social change—by addressing unmet needs—through the development of new programs and initiatives or adaptations to the focus of existing programs as a result of emergent need (Shier and Graham 2013). The relationship between both these types of innovation and the implications for social change has been underexplored in current scholarship.

It is possible that administrative innovations within organizations could have a social change impact. However, in the present study they were excluded in the operationalization of social innovation types because their primary purpose is not for social change, but rather to promote improved organizational practices of efficiency, accountability, and effectiveness. The impact on social change that these innovation types within nonprofits might have is secondary to some other intended organizational purpose. Whereas the purpose of product and process-based innovations is primarily geared toward creating social change with the intended purpose of better meeting service user social outcomes.

A final differentiation within the innovation scholarship describing the ways that direct service nonprofits create social change is through the development and implementation of socially transformative programs and initiatives. It is within this category of social change efforts that most of the recent scholarship has focused attention—and primarily around the role of direct service nonprofits in participating in political advocacy efforts (Almog-Bar and Schmid 2014). However, this category is more complicated and nuanced than engaging in political advocacy efforts that aim to influence public policy. Following post-modern organizational theory, which emphasizes the influence of socio-cultural, socio-political, and political-economic aspects of the organization’s external environment (Evers 2009; Hasenfeld 2010; Mulroy 2004), organizations undertake programs and initiatives that seek to address systemic issues within society. For example, organizations might seek to address issues related to social inequality and oppression and negative public perceptions and stereotypes. Netting et al. (2007) refer to these as ‘transformative’ programs or initiatives (herein referred to as socially transformative programs and initiatives), as they are intended to create social change within social service delivery systems and/or within society more generally.

Socially transformative programs and initiatives are those that do at least one of three things: (1) Challenge existing social/public policy; (2) promote social development or community participation; or (3) seek to change negative public perceptions toward a particular issue or service user group (Netting et al. 2007). Some examples of how these areas may be manifested include, but not limited to: (1) A lobbying or social action effort to address inequality in income security programs or eligibility criteria; (2) a new service delivery program bringing self-advocate service users together; (3) participation in a formalized policy planning meeting; (4) an initiative that connects service users with community members; or (5) an education campaign done through web-based media to counter negative stereotypes about a particular group in society (Guo and Saxton 2014; Kluver 2004; Netting et al. 2007).

As this literature suggests, product, process, and socially transformative innovations can all act to create social change at different levels of direct practice. And, as a collective, these different types of social innovation provide a more comprehensive understanding of the varied ways in which direct service nonprofits promote social change. Using this framework, we examine the three different ways (product, process, and socially transformative innovations), that direct service nonprofits create social change in their local communities and for service users.

Methods

To test the utility of this conceptual framework of social change, within direct service nonprofits, survey data were collected in late 2013 through to early 2014 from a random sample of 600 direct service nonprofits in Alberta, Canada. The research utilized a mixed methods study design, first collecting cross-sectional survey data from a random sample of executive directors of direct service nonprofits (n = 241, 40.2 % response rate) with follow-up interviews with executive directors of a random sample of participating organizations (n = 31). A mixed methods study design was utilized for two reasons. First, mixed methods designs can be particularly useful in explaining qualitatively the results of quantitative data (Creswell and Plano Clark 2006). In this particular case, the quantitative findings provide a model of social innovation within direct service nonprofits, and highlights important classifications within a more general construct of social innovation. The interview guide was developed based on this quantitative analysis to provide greater insight into the direct ways in which these various forms of social innovation are manifested within nonprofits. Second, the qualitative findings support the further advancement—through increasing specificity—of a measure of social innovation that is specifically applicable to direct service nonprofits.

Sample and Recruitment

Organizations were randomly selected from a publicly accessible list of nonprofit organizations in Alberta, Canada, made available through the Canada Revenue Agency. At the time of study, there were 8,902 charitable nonprofit organizations in Alberta, Canada. A sample frame was developed by carefully reviewing the websites and other available online information of these organizations to determine if they met the key inclusion criterion of the study; that being the organization provides direct social services to a population of service users. Direct social services included some level of social, psychological, or economic support to individual service users.

In total, there were 898 direct social service nonprofit organizations included in the sample frame. Based on initial pilot work, which elicited a 33 % response rate, with a random sample of 50 nonprofit organizations, 600 organizations were randomly sampled from the sample frame to attain an expected sample size of 200 organizations.

For the survey stage of the research, organizations were recruited following an active recruitment process that is designed to enhance response rates, and includes a series of recruitment and follow-up notices directly addressed to the intended respondent (Dillman 2000). Executive directors were selected because they are within positions in the organization that are most likely to be challenged in their job duties by the factors external to the organization, and therefore the most likely to make decisions on how to react. For the follow-up interview stage of the research, a random sample (n = 50) of executive directors that indicated (N = 189) they would be willing to participate in a follow-up qualitative interview were contacted first by email then through a telephone call. A random seed number was used, and individuals were sampled from the list of 189 organizations until 50 were selected. This process elicited a 62 % response rate with 31 executive directors participating. No further recruitment was undertaken as saturation was reached with the data collected.

This study received ethics certification from the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures and Data Collection

The scale for this study (The Human Services Social Innovation Scale) was created by reviewing the work of Damanpour (1987) and Perri (1993), whose work has been seminal in discussions of the varying innovation types in organizations (including administrative, product, or process focused innovations). Their work highlights a number of important considerations for what acts as an example of innovation within organizations. Such as the products that are provided to consumers (or service users in the case of social service nonprofits), the processes that organizations engage in to achieve their outcomes, and the structure of organizational units to meet underlying objectives. However, missing from this innovation literature is the inclusion of change efforts that seek to create socially transformative change. Based on a review of current literature pertaining to transformative programs and initiatives (Evers 2009; Hasenfeld 2010; Mulroy 2004; Netting et al. 2007) and earlier preliminary qualitative case study research conducted by Shier (2010) with a sample of 7 organizations in 4 different Canadian provinces, items were developed to measure the range of activities organizations are involved in to create socially transformative change. The final draft of the measure of social innovation for which data were collected included 15 items, measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from never to very frequently. Respondents were asked to rate the extent to which their organizations had engaged in each type of activity over the last three years.

Survey data were collected with the aid of the online Survey Monkey® platform. Qualitative data were collected through one to one interviews, following standard interviewing techniques for qualitative research (Fetterman 2008; Holstein and Gubrium 1995). The interview guide was informed by the survey results, with the intention of providing greater clarity on the specific ways each of product, process, and socially transformative social innovations were manifested in their organization’s behavior. For those respondents that lived in Calgary, Alberta, the interviews were conducted in person. For those outside of the Calgary area, interviews were conducted over the telephone. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes, and were digitally recorded and later transcribed. Respondents were asked questions about the ways in which they seek to create social change. For example, respondents were asked: What are some of the ways that your organization has tried to address some wider systemic issues impacting your service users or the community more generally; and, how does your direct engagement with service users impact the types of social change efforts your organization undertakes?

Data Analysis

The 15-item Human Services Social Innovation Scale was factor analyzed through a process of exploratory principal factor analysis, with the aid of the SAS 9.4 statistical software package (SAS Institute Inc. 2013). The intention of the analytical model was to determine if there were underlying constructs for the 15 items that were associated in a meaningful and coherent way. A maximum-likelihood extraction method with oblique rotation was used since it was expected that the multiple factors would be related to one another (see Kline and Graham 2009). As a result of missing data on 21 cases, the covariance matrix of multiple-imputed datasets was used to undertake the analysis.

Multiple factor solutions were proposed through an exploratory analysis using Bartlett’s test, parallel analysis, and minimum average partialling (MAP). However, the following criteria were used to determine the most ideal factor structure:

-

(1)

The model had a simple structure, reflected in the absence of item loadings on more than one factor and overall item coverage;

-

(2)

There were at least three salient items loaded on a given factor, in which salience is determined by loadings that are ≥0.40;

-

(3)

The factors were internally consistent (i.e., r ≥ 0.70);

-

(4)

The hyperplane count was maximized; and

-

(5)

The items on the factors made theoretical sense.

Regarding the qualitative interviews, the data were analyzed following standard processes of analytic induction and constant comparison strategies utilized for qualitative research (see Goetz and Lecompte 1984; Glaser and Strauss 1967) to detect emergent themes (Charmaz 2000) and patterns (Fetterman 2008) within the transcribed interviews. Specifically, emergent themes and patterns were identified with a focus on the ways that organizations seek to create social change for their service users and within the community more generally in relation to product, process, and socially transformative social innovation efforts. Initially, the interviews were read by the researcher with the objective of identifying common themes. The themes were then coded and searched for instances of the same or similar phenomena. Finally, the data were translated into more general working categories that were refined until all instances of contradictions, similarities, and differences within the interview transcripts were explained, thus increasing the dependability and consistency of the findings.

Results

Sample Descriptives

In total, 241 executive directors of nonprofits in Alberta, Canada participated in this survey research. The sample, where data were available, was comprised of 72 males (30.4 %) and 165 females (69.6 %). The average age of respondents was 51 years, with a range of 24–75 years, and on average they had been employed in their current positions for 8.91 years, with a range of 0.2–41 years. The majority of respondents (92.1 %) had completed a post-secondary education program. As is expected with a random sample, executive directors represented a range of service delivery areas, including counseling services, housing support services, shelter services, mental health services and addictions treatment, hospice and end of life care, disability support services, food security, employment supports, youth and child care services, among others. The average age of participating organizations was 25 years with a range of 2 years to more than 50. There was a great deal of variability in the size of the organizations. The average number of paid employees was 69 with a range of 0–1,400, and the average annual revenues were with a range of $5,000 to over $100,000,000. Organizations also represented a variety of communities throughout the province of Alberta. The majority of respondents (58.1 %) were located in Calgary or Edmonton (the two largest cities in Alberta, each with a population of over 1,000,000 people). However, 18.7 % were located in smaller cities with populations between 30,000 and 100,000, and 23.2 % were in smaller or remote communities with populations under 30,000.

Human Services Social Innovation Scale: Factor Analysis

Based on the criteria specified for a sufficient factor structure, the 3-factor promax (power = 2) solution was found to be optimal to analyze the 15-item Human Services Social Innovation Scale. As a result of this analysis, 12 items loaded on one and only one of each of the three factors. The remaining three did not meet the threshold of 0.40 that was set for the factor loading. The three salient factors were titled ‘Socially Transformative Social Innovations,’ ‘Product Based Social Innovations,’ and ‘Process Based Social Innovations.’ Forty-five percent of the variance in these 12 items was explained by the final factor structure. The 12 items, along with the corresponding factor loadings and communality estimates are provided in Table 1.

The reliability of the factors was assessed using Cronbach’s α measure of internal consistency. The Cronbach’s α reliability coefficients for the subscales of the social innovation scale were as follows: socially transformative social innovations (0.71), product-based social innovations (0.76), and process-based social innovations (0.74). All the subscales had acceptable reliability.

A further factor analysis was undertaken to determine if there was a higher order factor structure to the scale. In this case, because there is only one factor to be retained, an orthogonal method (i.e., varimax) of exploratory principal factor analysis was utilized. Total raw scores for each of the three factors were calculated and used for this analysis. Each factor loaded on a single higher order factor which was titled the Human Services Social Innovation Scale. The factor loadings for each of the constructs on the higher order factor structure were as follows: socially transformative social innovations (0.68), product-based social innovations (0.88), and process-based social innovations (0.54). The reliability estimate, measured by the Cronbach’s α measure of internal consistency for this total scale is 0.73.

Human Services Social Innovations

The following section describes the operationalization of the empirical model of three social innovations in practice: socially transformative, product, and process innovations. Interview participants (n = 31) represented a range of direct service areas; including counseling, domestic violence, housing and homelessness, employment, disability services, food security, mental health, addictions, newcomer integration, long-term care and disability, among others. Of the 31 participants, 7 were male and 24 were female. The average age of respondents was 53.8 years old, and they had been, on average, in their current positions for the last 8.9 years. In line with the empirical model presented previously, respondents identified being engaged in social change efforts that were socially transformative, product based, and process based. These qualitative findings provide more in depth insight into the various ways that nonprofits go about creating social change at various levels of practice.

Socially Transformative Social Innovations

Two thematic categories emerged within the qualitative data for socially transformative social innovations: (1) Creating public awareness; and (2) influencing policy directions.

Regarding creating public awareness, respondents identified three distinct areas in which they seek to create social change through their efforts at raising public awareness toward a particular social issue or service user population. The first is through education initiatives that are targeted specifically at the general community or key stakeholders within their service area or sector. For some respondents, creating education campaigns aided in informing the public and key stakeholders about the issues that individuals are experiencing in their local community. For example, a few organizations described their role in providing information to families and other stakeholders to equip those individuals with accurate information about what was happening to the level of services that their family members were receiving. Other organizations described hosting regular community luncheons or gatherings to educate community members about the types of services they offer and the underlying reasons why the services were necessary. Similarly, some organizations described undertaking more formalized public education campaigns.

The second area in which respondents identified creating public awareness is through efforts to promote community engagement. Some organizations described involving community members in discussions to help identify specific ways in which the community member can help to create social change. In these cases, the organization acts as a catalyst for helping to mobilize these efforts. Similarly, other respondents described that through their public awareness initiatives they emphasized ways in which people could become involved, rather than just providing information about the problems that are persistent in their community. Several respondents emphasized the need to engage individuals in a discussion about the ways in which they can support social change beyond the day to day operations of the organization.

The third area in which respondents identified creating public awareness is through efforts to change public perceptions about a particular social issue or service user population. Some respondents here described engaging with key stakeholder groups in the community within their programming efforts to address issues to help change negative perspectives or stereotypes held of certain groups of individuals. Other respondents described undertaking formalized community information sessions, which involved gathering information and sharing that information with the general community in situations where the negative perspectives of a specific service user population was receiving community level backlash.

Respondents also indicated that they were seeking to address negative public perceptions of particular social issues on a larger scale. For instance, organizations providing mental health and counseling-based services created larger scale campaigns to bring awareness to the issues of mental illness in the community to aid in reducing stigma. Capturing some of these ideas, one respondent from a children’s mental health services organization that utilizes residential support models described:

We do all kinds of things to try to change the perceptions of communities. For instance, one area in [respondent names city], we have a transition home there, and for our 100th year they are doing a 100 random acts of kindness for the community. Even though we still have people who complain about us, it is definitely that NIMBY [Not In My Back Yard] thing, we take the high road when that happens. And I think it is very small attempts at what I would call social change (024).

As another example of this thematic category, another respondent from an organization that provided food support to school aged children described:

We use feeding kids as a platform. Using the act of providing a lunch for a child as the inspiration or as the catalyst for social change. Because that creates social change for who is being helped and who is doing the helping (031).

Influencing policy direction was the second way that respondents described undertaking socially transformative social innovations. Respondents identified four general ways that they act to influence public policy direction. The first is through efforts at bringing information forward to key decision makers. For some respondents, this involved engaging in conversations, with empirical data, with funder organizations about the needs of their service users and changes within their local communities. Other respondents described efforts aimed at non-political stakeholders. For instance, a local mental health organization hosted a local conference with employers to provide information about ways to make workplaces more friendly and accommodating. Other organizations described less structured approaches by engaging with social media technology to provide information to the general public and to key stakeholder groups.

The second way that participating organizations identified that they influence policy direction is by undertaking research to influence how models of service delivery or methods of intervention are defined through legislation and government funders. For some respondents, this process involved engagement with service users to identify gaps in the service delivery system.

Other organizations described undertaking policy analysis to look at effects on service users and their outcomes and using that analysis to structure discussion with political leaders around the impacts of new policy direction on their service users and within the community more generally. Similarly, some respondents described undertaking larger scale research projects, through partnerships with academic institutions, to develop some policy-related technical reports to aid the government in their decision making processes.

A third way—and the most commonly reported way by respondents—of influencing policy direction is through discussions in networks of local and provincial nonprofit service providers. In many instances, respondents identified that the intention of these networks is to increase the capacity of individual nonprofit organizations in their efforts to influence the direction of public policy within their municipal district and across the province. Respondents described participating in groups that are focused on more widely impacting social issues, such as poverty, and also being engaged in specific sector related service provider groups. For many respondents, these networks were utilized to collectively discuss the issues that are having the greatest impact on their service user populations and to bridge service delivery organizations and sectors around some common goals and messages. Other respondents described involvement in national networks and with international academic communities interested in their particular approaches and models of practice.

Finally, the fourth way—and least reported way—that respondents described having an influence on public policy directions was through invited participation in formal gatherings that were aimed specifically at changing public policy. For all cases reported, this process involved being formally invited by the government to participate in discussions and provide input on the focus of the policy direction. Capturing some of these ideas, one respondent from a long-term care nonprofit described participating in a local initiative with the municipal government around creating a more accessible city. This respondent described:

One of the things that we are doing, and we started about three years ago now, we hosted a forum in [respondent names city] broadly looking at seniors issues. We looked at the Age Friendly Communities framework, and had people comment on that relative to their view of the world or area of practice. Out of that initiative we developed a bit of a relationship with the city government, who had taken a position of wanting to create an Age Friendly city. And out of that we have been working with the City, and we are now in the process of doing a series of community forums in one geographic area to map out what an Age friendly community would look like here. So that forum, in conjunction with the city, is supposed to go to the cities social planning committee this summer (017).

As another example one local organization working with youth around employment access, described the role of a local network involving the Chamber of Commerce, the public school system, other youth serving nonprofits in the community, and representatives from two leading post-secondary institutions in the city:

The intention of the network is to bring the public school perspective to the business and post-secondary education communities. By bringing our voices to the other members and having that information intersect. We can help those employers to understand what is happening in the school systems and what is lacking. And certainly that the chamber perspective is a good lobby group, and they can then have the potential to impact some change and put some pressure on different political groups if need be (011).

Product-Based Social Innovations

Product-based social innovations are important because they address limitations in existing service delivery models by creating new programs (and even organizations in some cases) to meet emerging need that is a result of changes in the external environment. Three thematic categories emerged for product-based social innovations. For the first, respondents described efforts at creating more inclusive services. Respondents identified several ways that they create social change by creating new services to be more inclusive of the range of service users able to access services. For instance, some organizations described extending services beyond a particular age threshold determined by funders. Others described creating new programming to be more inclusive of the needs of their changing demographic population. And some respondents described creating new inter-professional teams, or amalgamating the services of multiple organizations into a single organization, to address the interrelationship between social needs. Capturing some of these ideas, one respondent described creating social enterprise businesses within their organization to support inclusion of developmentally delayed adults within the labor market:

A lot of our businesses began as a structure around individuals who were vulnerable who needed some kind of infrastructure or support them to be a contributor. Catering, we had a group of staff who were great cooks, and three or four individuals that expressed an interest in food services and they wanted to be in the food services industry but they didn’t want to wash dishes for the rest of their lives. The idea serving food and contributing with food prep is meaningful to a lot of people because everybody eats. And so rather than finding people jobs in dish rooms, which we did initially, we started our own catering company and got people to participate in food prep. We now own three cafeterias and a catering group that serves about 1000 meals a day (023).

For the second thematic category of product-based social innovations, respondents described adapting existing programming as a means to create social change for their service user population. The underlying intention of these social change efforts was to create better outcomes for service users. For some respondents, this involved incorporating new intervention models in their existing service delivery programs. For other respondents, the adaptation was not just to individual programs, but included the incorporation of multiple services in a single location through formal inter-agency networks to create service delivery hubs for individuals, or by linking multiple programs within a single organization. Capturing some of these ideas, one respondent from a counseling services organization described changing the therapeutic format for treating people with depression:

And the new protocol is based on the evidence we collected. And the evidence tells us that after about 6 or 7 sessions of individual client counseling, that a client starts to deteriorate, but those clients that can be moved to group are changing two standard deviations across the mean. So the combination of individual and group therapy is way more powerful than individual therapy alone, and provides an opportunity for longer sustainable change (025).

A final way that organizations described creating social change through product-based social innovations was by changing the general focus of their efforts with service users. For some respondents, this included changing the focus of how they intervened with service users. Essentially, these respondents described adapting the focus of ‘where they meet their clients’; meaning where they start their work with their clients. Other respondents described a change in the general focus in their approaches to client engagement and the types of service delivery models that were offered. Capturing some of these ideas, one respondent described the need to change the focus of their intervention in supporting families with disabled children. As this respondent describes, supporting families to meet basic needs has recently become an instrumental step in their helping process:

One of the longstanding issues has been housing. And for families to find a place that is large enough and affordable. So that has impacted our ability to support families adequately. Lots of times, because of the economic climate, we work with families on housing supports, just meeting basic needs, as opposed to working on the next step which is to work with the family around supports for their disabled child. So the economic climate can shift some of our support model so we can provide them with some basic need information and support. And we realize that is a step we have to take before we can work with the family around the child with a disability (007).

Process-Based Social Innovations

Process-based social innovations are adaptations made at the organizational level that aim to support the organization in their social change efforts. Two thematic categories emerged around process-based social innovations. For the first, respondents described adaptations to methods of engagement with key stakeholder groups. The first group is service users. Some respondents described changing the general way that they approached their mission, essentially moving from a more restrictive service delivery support model to a model of engagement that sought input from service users. Other respondents described including service users in governance structures of their organization, or including structured processes of getting feedback from service users to help better align programs with their perceived needs.

The second area in which engagement processes were adapted by respondents was with other organizations. Many respondents described the need to work collaboratively with other nonprofit or public organizations to address the range of issues that individual service users were experiencing. Some respondents described developing partnerships in order for them to meet their intended program goals, and others came together among organizations with a common interest.

To a lesser extent, some organizations described adapting the way that they engaged with funders. For instance, respondents described creating sustainable funding through the development of social enterprise businesses, or establishing their programming within a funding model of fee for service. In both cases, organizations are able to establish the costs associated with a particular service, and the funder (or customer) themselves can determine if they are going to utilize that service.

The fourth area in which respondents described adapting their engagement processes was with organization staff. For many respondents, this took on the form of increased training and awareness exercises around the relationship between staff and service users and creating a learning culture within the organization around some of the underlying issues that are impacting service user groups. Capturing some of these ideas, one respondent from a disability children’s service organization described:

I am meeting with [respondent names organization], and part of my proposal is that they have staff from September until June, and then when kids are out of school they have no contact. But they have developed those relationships, so what if we could support that ongoing relationship. Because we get the funding for the summer to do the camps, could we take their staff, or however this would work, where the kids that they are supporting could go to a camp and continue to get that support by a staff member that they are already comfortable with (013).

The second way that process-based social innovations were manifested in organizations was through adaptations to organizational practices, processes, and structure. Some respondents described adaptations to operational aspects of their organizations to create social change. A few organizations described the creation of new positions within their organization that were orientated directly toward advocacy. Other respondents described the need to change the hours that they operated to better meet the needs of services users. Some organizations described the need to implement practices within their organization where staff were cross-trained to other positions to increase awareness of the interrelationship between departments and the need to work together to solve the underlying issues that individuals were presenting.

Capturing some of these ideas, one respondent described how previously, individual workers would be responsible for dealing with advocacy-related issues as they emerged with individual service users. A more structured approach, by having a centralized person tasked with tracking these challenges, enables the organization to undertake a more focused effort towards social change. This respondent describes:

We have a position on staff, an advocacy coordinator, and that position, anybody, a family member of someone living with mental illness or somebody with mental illness, can call that individual if they feel they are not getting access, that advocacy coordinator can assist that person in getting access. It is a new position in the agency, and we are streaming those service requests so we can see if there is one major area that needs to be addressed, and then we can focus the systemic advocacy around that (029).

Discussion

The findings from the thematic analysis are summarized in Table 2. Overall, the qualitative findings support the item level analysis undertaken by exploratory factor analysis. For instance, with regard to socially transformative social innovations, four items were found to sufficiently load (and give meaning) to this particular construct. From Table 1, socially transformative social innovations include undertaking activities to change public perceptions, to promote social inclusion, engage in activities that might foster social cohesion within the community more generally, and to incorporate research-related initiatives to better identify and assess need. Interview respondents from the qualitative component of this study highlighted specific ways that they go about achieving these ends through general thematic categories of public awareness and influencing public policy.

Similarly, for the item level analysis for the product-based social innovations, this construct includes adaptations to, or the creation of, new programs, services, or intervention approaches. The qualitative findings suggest the impetus for these social innovations is through tangible adaptations to existing programs, by creating programs that are more inclusive by extending inclusion criteria, and changing the general focus of their efforts in response to changing demographic and community need. Finally, the item level analysis for process-based social innovations characterizes this construct in terms of efforts at changing inter-personal interactions within the organization and with service users and creating new positions and/or administrative departments to better meet the needs of services users. The qualitative findings further enhance this item level analysis by highlighting key stakeholder groups that are the focus of changing inter-personal dynamics within and beyond organizations, along with identifying specific organizational structures and positions that can be supportive in creating a more social change orientated organization.

While the quantitative findings provide a valid and reliable measure of the social innovation efforts of direct service nonprofits through the Human Services Social Innovation Scale, the qualitative findings provide a clearer definition of the ways that these varying social innovation types are manifested in direct organizational practice. On a theoretical level, these combined mixed methods findings highlight that advocacy and service delivery are mutually reinforcing, and embedded in multiple social change efforts undertaken within and between organizations. This is a contrasting finding to previous research that has tended to create dichotomies between service delivery and advocacy, suggesting that these two roles are distinct (Moulton and Eckerd 2012; Valentinov et al. 2013). Instead, the framework presented by the qualitative interviews in particular highlights the complex interrelationship between systemic social change and service delivery, and the multiple ways that social change efforts are manifested within direct service nonprofits. In fact, one of the interesting findings that emerged from this study is that direct service nonprofits might be engaged in political advocacy-related activities (such as participating in invited networks to shape policy, or working in inter-agency collaborations to discuss limitations of existing policy), but many did not see these activities as being particularly useful with regard to the level of impact that these efforts have on influencing public policy direction. Instead, respondents identified being engaged in activities associated with creating public awareness, or undertaking research-based initiatives, suggesting that systemic social change is about more than just aiming to shape public policy.

The findings from this study also provide a foundation for further research. While the qualitative interviews provide an analytical framework of the tangible ways that direct service organizations create social change, and is generally supportive of the item level analysis, the qualitative findings also provide a starting point to further develop the empirical scale. The intention of such an effort would be to offer greater specificity of the measurement of the various social change efforts undertaken by direct service nonprofits. For instance, while the four items used to measure socially transformative social innovations generally apply to the qualitative findings, the interview respondents were very specific on the types of efforts that they engage in to create this type of social change. The scale could therefore be adapted to include greater item coverage on the various ways that organizations actually engage in these types of social change efforts. Similarly, while items were included in the subscale of process-based social innovation that related to the inter-personal interactions within organizations, greater item coverage could be included in an adapted version of the scale for each of the different stakeholder groups identified. Or more specifically, efforts by organizations to provide the training to help staff and volunteers see beyond the challenges of individual clients, and look more generally toward the impact of the external environment on their service user population. Of course, one of the challenges with increasing specificity for a scale on social innovation is the extent to which the scale is up to date. Organizations are changing and finding new ways to be innovative. Increasing specificity may act to limit (or constrain) what is understood to be social innovation at a given point in time.

There are a few limitations to this study. The first is with regard to representativeness. Respondents in both phases of the research were informed about the purpose of the study. This may have resulted in some level of non-participation by executive directors that do not perceive their organization as being orientated toward this social change related role. However, in both stages of the study, random samples were used in order to address some of this nonresponse bias. Efforts at better representativeness were also achieved by having a diverse mix of organizations in general service area and geographic location in this provincial study.

Second, the study did not seek to measure the impact of these social change efforts. While the Human Services Social Innovation Scale might demonstrate sufficient factorial validity, and provides a measure of the extent to which organizations engage in these three forms of social innovation, it does not provide a measure of the level of impact these innovation types has on achieving social change. Further research in this regard is warranted.

Finally, while item level wording in the Human Services Social Innovation Scale suggests that organizations were responding to service user identified need when reflecting on their social change efforts, this was something that could not be measured or assessed in either of the mixed methods stages. It could have been the case that some of the reported social innovation by respondents was in response to professional identified client need, rather than based holistically on the actual experiences from the perspectives of service users. As this program of research moves forward, it would be important to be able to differentiate between different types of motivation when engaging in social change efforts, along with identifying where the impetus for the social change effort emerged.

Implications

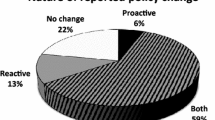

The findings have implications for direct service nonprofits that are seeking to create social change. Understanding social change from a conceptual model of social innovation, as opposed to a model of political advocacy, highlights the varied ways that direct service nonprofits are creating social change for their service users and within their communities. As respondents here point out, creating social change is not just done through political advocacy based efforts, but through a concerted effort of change initiatives implemented at services user, programmatic, organizational, community, and socio-political levels of practice, from a very diverse sector of nonprofit organizations. Together, this conceptual model of social change highlights the proactive role of direct service nonprofits in creating social change, rather than simply being reactive agents to an inequitable public policy framework.

Furthermore, the findings from this study also have implications for education programs that seek to train leaders of direct service nonprofits. While there has not been any formal analysis undertaken of programs in schools of social work on the structure of course content around nonprofit organizations, Mirabella (2007) has reviewed graduate level programs around nonprofit leadership. However, within that study, Mirabella (2007) shows that the emphasis is primarily on the internal management practices of organizational leaders, with little emphasis on the role of nonprofit leaders in creating social change. The findings from this study highlight the active role played by a diverse range of direct service nonprofits within their external environments. As direct service nonprofits take on an increasing presence within their communities, and in the absence of government direction in creating improved outcomes for service users, greater attention needs to be made in nonprofit leadership, social work, and other allied discipline education programs that aim to develop the skills and training needed to successfully support social change.

References

Almog-Bar, M., & Schmid, H. (2014). Advocacy activities of nonprofit human service organizations: A critical review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(1), 11–35.

Alvord, S., Brown, L., & Letts, C. (2004). Social entrepreneurship and societal transformation: An exploratory study. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 40(3), 219–232.

Anheier, H. (2009). What kind of non-profit sector, what kind of society? Comparative policy reflections. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(7), 1082–1094.

Borzaga, C., & Bodini, R. (2014). What to make of social innovation? Towards a framework for policy development. Social Policy and Society, 13(3), 411–421.

Boyd, N. M. (2011). Helping organizations help others: Organization development as a facilitator of social change. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community, 39, 5–18.

Boyd, A. S., & Wilmoth, M. C. (2006). An innovative community-based intervention for African American women with breast cancer: The Witness Project. Health and Social Work, 31(1), 77–80.

Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructionist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 509–535). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Child, C., & Gronbjerg, K. (2007). Nonprofit advocacy organizations: Their characteristics and activities. Social Science Quarterly, 88(1), 259–281.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2006). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Damanpour, F. (1987). The adoption of technological, administrative, and ancillary innovations: Impact of organizational factors. Journal of Management, 13(4), 675–688.

Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and internet surveys: The tailored design method. New York: Wiley.

Evers, A. (2009). Civicness and civility: Their meanings for social services. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 20, 239–259.

Fetterman, D. M. (2008). Ethnography. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (pp. 288–292). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine Press.

Goetz, J. P., & LeCompte, M. P. (1984). Ethnography and qualitative design in educational research. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Grohs, S., Schneiders, K., & Heinze, R. G. (2013). Social entrepreneurship vs. intrapreneurship in the German social welfare state: A study of old-age care and youth welfare services. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. doi:10.1177/0899764013501234

Guo, C., & Saxton, G. (2014). Tweeting for social change: How social media are changing nonprofit advocacy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(1), 57–79.

Hasenfeld, Y. (Ed.). (2010). Human services as complex organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (1995). The active interview. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press.

Ife, J. (1996). Community development: Creating community alternatives—Vision, analysis and practice. Melbourne, AU: Addison Wesley Longman.

Jaskyte, K., & Lee, M. (2006). Interorganizational relationships: A source of innovation in nonprofit organizations? Administration in Social Work, 30(3), 43–54.

Jones, J. M. (2006). Understanding environmental influence on human service organizations: A study of the influence of managed care on child caring institutions. Administration in Social Work, 30(4), 63–90.

Kimberlin, S. E. (2010). Advocacy by nonprofits: Roles and practices of core advocacy organizations and direct service organizations. Journal of Policy Practice, 9, 164–182.

Kline, T., & Graham, J. R. (2009). The social worker satisfaction scale. Canadian Social Work, 11(1), 53–59.

Kluver, J. D. (2004). Disguising social change: The role of nonprofit organizations as protective masks for citizen participation. Administrative Theory and Praxis, 26(3), 309–324.

Mano, R. S. (2009). Information technology, adaptation and innovation in nonprofit human service organizations. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 27(3), 227–234.

Mellinger, M. S. (2014). Beyond legislative advocacy: Exploring agency, legal, and community advocacy. Journal of Policy Practice, 13(1), 45–58.

Mirabella, R. M. (2007). University based educational programs in nonprofit management and philanthropic studies: A 10-year review and projections of future trends. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(4), 11S–27S.

Mosley, J. E., & Ros, A. (2011). Nonprofit agencies in public child welfare: Their role and involvement in policy advocacy. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 5, 297–317.

Moulton, S., & Eckerd, A. (2012). Preserving the publicness of the nonprofit sector: Resources, roles, and public values. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(4), 656–685.

Mulroy, E. A. (2004). Theoretical perspectives on the social environment to guide management and community practice: An organization-in-environment approach. Administration in Social Work, 28(1), 77–96.

Murray, C. E. (2009). Diffusion of innovation theory: A bridge for the research-practice gap in counseling. Journal of Counseling and Development, 87(1), 108–116.

Netting, F. E., O’Connor, M. K., & Fauri, D. P. (2007). Planning transformative programs: Challenges for advocates in translating change processes into effectiveness measures. Administration in Social Work, 31(4), 59–81.

Nichols, A. (Ed.). (2006). Social entrepreneurship: New models of sustainable social change. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Perri 6. (1993). Innovation by nonprofit organizations: Policy and research issues. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 3(4), 397–414.

Pol, E., & Ville, S. (2009). Social innovation: Buzz word or enduring term? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 38(6), 878–885.

Powell, F. P. (2007). The politics of civil society: Neoliberalism or social left?. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Prince, J., & Austin, M. J. (2001). Innovative programs and practices emerging from the implementation of welfare reform: A cross-case analysis. Journal of Community Practice, 9(3), 1–14.

Salamon, L. (2002). The state of nonprofit America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

SAS Institute Inc. (2013). SAS® 9.4 guide to software updates. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.

Schmid, H. (2004). The role of nonprofit human service organizations in providing social services: Prefatory essay. Admininstration in Social Work, 28(3/4), 1–21.

Schmid, H., Bar, M., & Nirel, R. (2008). Advocacy activities in nonprofit human service organizations: Implications for policy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37(4), 581–602.

Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Shier, M. L. (2010). Human service organizations and the social environment: Making connections between practice and theory. Unpublished Masters Thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

Shier, M. L., & Graham, J. R. (2013). Identifying social service needs of Muslims living in a post 9/11 era: The role of community-based organizations. Advances in Social Work, 14(2), 379–394.

Shier, M. L., McDougle, L. M., & Handy, F. (2014). Nonprofits and the promotion of civic engagement: A conceptual framework for understanding the ‘civic footprint’ of nonprofits within local communities. The Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research, 5(1), 57–75.

Simpson, D. D. (2009). Organizational readiness for stage-based dynamics of innovation implementation. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(5), 541–551.

Spergel, I. A., & Grossman, S. F. (1997). The Little Village Project: A community approach to the gang problem. Social Work, 42(5), 456–470.

Valentinov, V., Hielscher, S., & Pies, I. (2013). The meaning of nonprofit advocacy: An ordonomic perspective. The Social Science Journal, 50, 367–373.

Wood, S. A. (2007). The analysis of an innovative HIV-positive women’s support group. Social Work with Groups, 30(3), 9–28.

Acknowledgments

This research was possible due to the generous support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Resource Council of Canada’s Doctoral Fellowship Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shier, M.L., Handy, F. From Advocacy to Social Innovation: A Typology of Social Change Efforts by Nonprofits. Voluntas 26, 2581–2603 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9535-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9535-1