Abstract

The efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) in patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) remains unclear. We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library for randomized controlled trials (RCT) comparing DOACs versus aspirin in patients with ESUS. Risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed for binary endpoints. Four RCTs comprising 13,970 patients were included. Compared with aspirin, DOACs showed no significant reduction of recurrent stroke (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.84–1.09; p = 0.50; I2 = 0%), ischemic stroke or systemic embolism (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.80–1.17; p = 0.72; I2 = 0%), ischemic stroke (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.79–1.06; p = 0.23; I2 = 0%), and all-cause mortality (RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.87–1.42; p = 0.39; I2 = 0%). DOACs increased the risk of clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNB) (RR 1.52; 95% CI 1.20–1.93; p < 0.01; I2 = 7%) compared with aspirin, while no significant difference was observed in major bleeding between groups (RR 1.57; 95% CI 0.87–2.83; p = 0.14; I2 = 63%). In a subanalysis of patients with non-major risk factors for cardioembolism, there is no difference in recurrent stroke (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.67–1.42; p = 0.90; I2 = 0%), all-cause mortality (RR 1.24; 95% CI 0.58–2.66; p = 0.57; I2 = 0%), and major bleeding (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.32–3.08; p = 1.00; I2 = 0%) between groups. In patients with ESUS, DOACs did not reduce the risk of recurrent stroke, ischemic stroke or systemic embolism, or all-cause mortality. Although there was a significant increase in clinically relevant non-major bleeding, major bleeding was similar between DOACs and aspirin.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Highlights

-

It’s unclear if DOACs may be an effective and safe therapy in patients after ESUS.

-

New trials have been investigating DOACs in patients with “enriched” risk factors for cardioembolism after ESUS, which made possible a subanalysis for this population.

-

Our analyses demonstrated that DOACs did not reduce the risk of new strokes, all-cause mortality, and other efficacy outcomes.

-

Despite DOACs having decreased the risk of CNRB, there was no difference between groups regarding major bleeding.

Introduction

Ischemic stroke accounts for approximately 80% of all strokes and stands as a leading contributor to global morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) is characterized by non-lacunar cerebral infarcts without detectable embolic origins or significant arterial stenosis [3,4,5]. Its incidence varies widely across ischemic strokes, ranging from 7 to 42%, with an average of 17% [6].

Many patients with ESUS are believed to have undiagnosed atrial fibrillation (AF) [7]. According to several meta-analyses, oral anticoagulation surpasses antiplatelet therapy in effectively preventing strokes related to atrial fibrillation (AF), however its efficacy in patients with ESUS remains uncertain [8,9,10,11].

The lower stroke risk of younger patients with atrial fibrillation and without other cardiovascular risk factors may imply additional causes underlying cardioembolism other than atrial fibrillation [12]. A prior meta-analysis found no benefit of direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC) over aspirin in these patients [13]. However, this study showed no data about patients with non-major risk factors for cardioembolism, which made it impossible to investigate the benefit of anticoagulation in this specific context of patients with ESUS.

Two recent randomized controlled trials (RCT) evaluated DOACs in patients with the definition of ESUS and non-major risk factors for cardioembolism, enabling a subanalysis for these patients [14, 15]. Therefore, we conducted an updated meta-analysis comparing DOACs with aspirin assessing new efficacy and safety endpoints, including ischemic stroke or systemic embolism and intracranial hemorrhage (ICH).

Methods

We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Cochrane Collaboration and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [16, 17]. The prospective protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42024511012).

Search strategy and data extraction

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library from inception to 8 February 2024 using the following terms: “ESUS”, “cryptogenic stroke”, “DOAC”, “direct oral anticoagulant”, “apixaban”, “rivaroxaban”, “edoxaban”, and “dabigatran”. The detailed search strategy is available in the Supplementary Table S1. Two investigators (G.M. and B.A.) independently screened the search results and performed data extraction using Microsoft Excel software. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third author (G.A.M.). Data extracted from each study included study characteristics (sample size, intervention characteristics, mean age, sex, race), population characteristics (mean CHA2DS2-VASc score, median NIHSS score, history of previous transient ischemic attack/stroke, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and tobacco use), and outcomes of interest.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were studies that met the following criteria: (1) were RCTs; (2) compared DOACs with aspirin for secondary stroke prevention in patients with ESUS; (3) reported data on at least one outcome of interest. Exclusion criteria included: (1) case reports, commentaries, abstracts, editorials, letters, and reviews; (2) studies with missing data on interventional or control therapy; (3) studies lacking relevant population or outcomes data. The detailed eligibility criteria of included studies are described in Supplementary Table S2.

Endpoints

Efficacy outcomes were recurrent stroke, ischemic stroke or systemic embolism, ischemic stroke, systemic embolism, hemorrhagic stroke, and all-cause mortality. Safety outcomes comprised major bleeding, clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNB), ICH, and any bleeding. The definitions of outcomes on each study are outlined in Supplementary Table S3.

Statistical analysis

We used Review Manager 5.4.1 for the main statistical analyses. Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed for binary endpoints. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochran Q test and I2 statistics, with p-values less than 0.10 and I2 ≥ 25% considered significant for heterogeneity. We employed DerSimonian and Laird random‐effects models. We also performed a subanalysis focused on patients with non-major risk factors of cardioembolism. Subgroup analysis was performed according to sex and age. In addition, sensitivity analyses were carried out employing the leave-one-out approach to evaluate the potential influence of individual studies on the heterogeneity of results using the software R (version 4.4.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The definitions of non-major risk factors of cardioembolism are described in Supplementary Table S4.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in randomized studies was assessed using Cochrane’s tool for assessing bias in randomized trials (RoB-2) [18]. Two independent authors (G.A.M. and B.A.) completed the risk of bias assessment, with any disagreements resolved through consensus after discussion with a third author (G.M.).

Results

Study selection and baseline characteristics

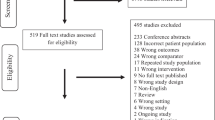

A total of 723 articles were retrieved in the initial search. After removing duplicates and screening by titles and abstracts, 56 studies underwent full review. Ultimately, four RCTs were included, encompassing 13,970 patients (Fig. 1) [14, 15, 19, 20]. Among included trials, one utilized rivaroxaban [20], two used apixaban [14, 15], and one employed dabigatran [19]. The mean age of participants was 66.8 years, with 60.7% being male. Of the total cohort, 76.2% had hypertension, and 17.8% had a previous history of stroke or transient ischemic attack. Detailed characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

Efficacy outcomes

Recurrent stroke occurred in 816 patients, with 399 (5.7%) receiving DOACs and 417 (5.9%) using aspirin. There was no significant difference between groups (RR 0.95; 95% CI 0.84–1.09; p = 0.50; I2 = 0%; Fig. 2A). All studies reported data for this outcome [14, 15, 19, 20].

There was no significant difference between DOACs and aspirin regarding the risk of ischemic stroke or systemic embolism (RR 0.97; 95% CI 0.80–1.17; p = 0.74; I2 = 0%; Fig. 2B). Similarly, no significant differences were observed between treatments for ischemic stroke (RR 0.92; 95% CI 0.79–1.06; p = 0.23; I2 = 0%; Fig. 2C), systemic embolism (RR 0.52; 95% CI 0.21–1.25; p = 0.14; I2 = 0%; Fig. 2D) and hemorrhagic stroke (RR 2.21; 95% CI 0.29–16.69; p = 0.44; I2 = 79%; Fig. 2E), and all-cause mortality (RR 1.11; 95% CI 0.87–1.42; p = 0.39; I2 = 0%; Fig. 2F). Three studies provided data for ischemic stroke, systemic embolism and hemorrhagic stroke [14, 19, 20]. Only one study provided no data about ischemic stroke or systemic embolism [19]. All studies reported data for all-cause mortality [14, 15, 19, 20].

Safety outcomes

In terms of major bleeding events, 145 patients were on DOACs (2.1%) and 93 (1.3%) were on aspirin. There was no significant difference observed between DOACs and aspirin (RR 1.57; 95% CI 0.87–2.83; p = 0.14; I2 = 63%; Fig. 3A). However, DOACs significantly increased the risk of clinically relevant non-major bleeding (CRNB) compared with aspirin (RR 1.52; 95% CI 1.20–1.93; p < 0.01; I2 = 7%; Fig. 3B). Nevertheless, no differences were observed in ICH (RR 1.09; 95% CI 0.26–4.63; p = 0.90; I2 = 81%; Fig. 3C) and any bleeding (RR 0.85; 95% CI 0.37–1.93; p = 0.70; I2 = 69%; Fig. 3D). All studies provided data about major bleeding and ICH [14, 15, 19, 20]. Only one study reported no data for CRNB [15] and any bleeding [20].

Sub-analysis and sensitivity analysis

In patients with non-major risk factors of cardioembolism, there was no significant difference between DOAC and aspirin regarding recurrent stroke (RR 0.98; 95% CI 0.67–1.42; p = 0.90; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Fig. S1A), ischemic stroke or systemic embolism (RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.62–1.31; p = 0.59; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Fig. S1B), or all-cause mortality (RR 1.24; 95% CI 0.58–2.66; p = 0.57; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Fig. S1C). No significant differences were found in major bleeding (RR 1.00; 95% CI 0.32–3.08; p = 1.00; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Fig. S1D) and any bleeding (RR 0.53; 95% CI 0.25–1.13; p = 0.10; I2 = 0%; Supplementary Fig. S1E) between DOACs and aspirin, and both results presented low heterogeneity. Our sensitivity analysis showed low heterogeneity in major bleeding and any bleeding after the leave-one-out approach. Regarding ICH, high heterogeneity remained after the withdrawal of each study. The sensitivity analyses are presented in Supplementary Figs. S2A–S3C.

Subgroup analysis

Regarding recurrent stroke, subgroup analysis showed no significant difference between groups when stratified by age and sex (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Risk of bias assessment

Individual assessments of each included study are presented in Supplementary Fig. S4. Overall, all included studies were deemed to be at low risk of bias.

Discussion

In this updated meta-analysis we compared the efficacy of DOACs versus aspirin in patients with ESUS. Overall, DOACs did not demonstrate a reduction in the risk of recurrent stroke or other efficacy outcomes compared with aspirin. Additionally, there were no significant differences in terms of major bleeding and any bleeding, although the risk of clinically relevant non-major bleeding was higher in patients receiving DOACs. Subanalysis of patients with evidence of suggestive features of cardioembolism showed no benefit from anticoagulant therapy.

Although anticoagulation benefits are confirmed mainly in patients with clinically apparent AF, even subclinical AF detected by prolonged heart-rhythm monitoring is associated with an increased stroke risk [21], likely due to underlying atrial cardiopathy and the arrhythmia itself [22, 23]. Although many patients with ESUS might have had an unrecognized source of cardiac embolism, including atrial fibrillation, previous studies found no benefit of anticoagulation in these patients [13, 19, 20]. In accordance, our findings maintained the same pattern. This could be attributed to various factors, including the likelihood that recurrent strokes post-ESUS may stem from causes different from the initial stroke [24]. In NAVIGATE ESUS (Rivaroxaban for Stroke Prevention after Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source), more than half of recurrent strokes were atherosclerotic or lacunar [24].

The Apixaban to Prevent Recurrence After Cryptogenic Stroke in Patients With Atrial Cardiopathy (ARCADIA) and Apixaban Versus Aspirin for Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source (ATTICUS) trials investigated the benefit of apixaban in ESUS patients with specific features suggestive of cardioembolism [14, 15]. These new trials enabled us to perform a subanalysis of this population, something not addressed by the prior meta-analysis [13]. In ARCADIA, the included patients had specific biomarkers of atrial cardiopathy including elevated PFTV1, serum NT-proBNP (N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide), and left atrial diameter on echocardiogram. Atrial cardiopathy is strongly associated with the development of AF, contributing to a multifaceted thromboembolic process [25]. ATTICUS was broader and included risk factors associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation and cardioembolism. Nevertheless, our subanalysis showed no significant difference for the efficacy and safety outcomes between DOACs and aspirin. Notably, ARCADIA reported a significantly lower risk of symptomatic ICH in participants receiving apixaban compared with aspirin, although the lower number of events may suggest it, this finding may be by chance [15]. In ATTICUS trial, there was no significant increase in the risk of major bleeding with apixaban, despite the early initiation of study treatment compared to NAVIGATE ESUS and RE-SPECT ESUS (Dabigatran for Prevention of Stroke after Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source) trials. Apixaban’s known similarity in the risk of major bleeding in patients with AF may explain this finding [26].

A previous meta-analysis that included two of the four RCTs included in the present meta-analysis also reported no superiority of anticoagulation over aspirin, although it noted moderate to high heterogeneity in some outcomes [13]. In contrast, our analysis found low heterogeneity in the risk of recurrent stroke (0%) and ischemic stroke (0%) with the inclusion of newer studies.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, few studies met the inclusion criteria, precluding Egger’s regression test and meta-regression analyses. Secondly, there was significant variability in the sample size of included studies, although there was a low heterogeneity in the majority of our endpoints. Thirdly, there was a considerably variable definition regarding definitions of non-major risk factors for cardioembolism between ARCADIA and ATTICUS. Fourth, ATTICUS was prematurely terminated, which may have limitated their results. Lastly, some outcomes were not directly reported or defined by some studies, limiting our analysis.

Conclusion

In patients with ESUS with or without non-major risk of cardioembolism, DOACs showed no significant reduction in the risk of recurrent stroke, ischemic stroke or systemic embolism, and all-cause mortality. Although there was a significant increase in clinically relevant non-major bleeding, major bleeding was similar between DOACS and aspirin.

Abbreviations

- ESUS:

-

Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source

- AF:

-

Atrial Fibrillation

- DOAC:

-

Direct Oral Anticoagulant

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- ICH:

-

Intracranial Hemorrhage

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- CRNB:

-

Clinically Relevant Non-Major Bleeding

- RR:

-

Risk Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Intervals

- RoB-2:

-

Cochrane’s Tool for Assessing Bias in Randomized Trials.

- NAVIGATE ESUS:

-

Rivaroxaban for Stroke Prevention after Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source

- ARCADIA:

-

Apixaban to Prevent Recurrence After Cryptogenic Stroke in Patients With Atrial Cardiopathy

- ATTICUS:

-

Apixaban Versus Aspirin for Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source

- RE-SPECT ESUS:

-

Dabigatran for Prevention of Stroke after Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source

References

Boehme AK, Esenwa C, Elkind MSV (2017) Stroke risk factors, genetics, and prevention. Circ Res 120:472–495. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.308398

Meschia JF, Brott T (2018) Ischaemic stroke. Euro J Neurol 25:35–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.13409

Saver JL (2016) Cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med 375:e26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1609156

Schäbitz WR, Köhrmann M, Schellinger PD et al (2020) Embolic stroke of undetermined source: gateway to a new stroke entity? Am J Med 133:795–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.005

Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB et al (2014) Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol 13:429–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70310-7

Hart RG, Catanese L, Perera KS et al (2017) Embolic stroke of undetermined source: a systematic review and clinical update. Stroke 48:867–872. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016414

Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P et al (2014) Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med 370:2467–2477. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1311376

Aguilar M, Hart R, Pearce L (2006) Oral anticoagulants versus antiplatelet therapy for preventing stroke in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and no history of stroke or transient ischemic attacks. In: The Cochrane Collaboration (ed) Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Wiley, Chichester

Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI (2007) Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 146:857. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007

Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E et al (2014) Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet 383:955–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

Tawfik A, Bielecki J, Krahn M et al (2016) Systematic review and network meta-analysis of stroke-prevention treatments in patients with atrial fibrillation. CPAA 8:93–107. https://doi.org/10.2147/CPAA.S105165

Chao TF, Liu CJ, Chen SJ et al (2012) Atrial fibrillation and the risk of ischemic stroke: does it still matter in patients with a CHA2 DS2-VASc score of 0 or 1? Stroke 43:2551–2555. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.667865

Hariharan NN, Patel K, Sikder O et al (2022) Oral anticoagulation versus antiplatelet therapy for secondary stroke prevention in patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Stroke J 7:92–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/23969873221076971

Geisler T, Keller T, Martus P et al (2023) Apixaban versus aspirin for embolic stroke of undetermined source. NEJM Evid. https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDoa2300235

Kamel H, Longstreth WT, Tirschwell DL et al (2024) Apixaban to prevent recurrence after cryptogenic stroke in patients with atrial cardiopathy: the ARCADIA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 331:573. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.27188

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535–b2535. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds) (2022) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 63 (updated February 2022). Cochrane Training, Cochrane

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ et al (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

Diener HC, Sacco RL, Easton JD et al (2019) Dabigatran for prevention of stroke after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med 380:1906–1917. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1813959

Hart RG, Sharma M, Mundl H et al (2018) Rivaroxaban for stroke prevention after embolic stroke of undetermined source. N Engl J Med 378:2191–2201. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1802686

Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR et al (2012) Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med 366:120–129. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105575

Kamel H, Okin PM, Elkind MSV, Iadecola C (2016) Atrial fibrillation and mechanisms of stroke: time for a new model. Stroke 47:895–900. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012004

Singer DE, Ziegler PD, Koehler JL et al (2021) Temporal association between episodes of atrial fibrillation and risk of ischemic stroke. JAMA Cardiol 6:1364. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2021.3702

Veltkamp R, Pearce LA, Korompoki E et al (2020) Characteristics of recurrent ischemic stroke after embolic stroke of undetermined source: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 77:1233. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1995

Hirsh BJ, Copeland-Halperin RS, Halperin JL (2015) Fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, and thromboembolism. J Am Coll Cardiol 65:2239–2251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.557

Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C et al (2011) Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 364:806–817. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1007432

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Marinheiro, G., Araújo, B., Rivera, A. et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in embolic stroke of undetermined source: an updated meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-024-03017-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-024-03017-7